Abstract

Background

Older people with dementia have increased risk of nursing home (NH) use and higher Medicaid payments. Dementia’s impact on acute care use and Medicare payments is less well understood.

Objectives

Identify trajectories of incident dementia and NH use, and (2) compare Medicare and Medicaid payments for persons having different trajectories.

Research Design

Retrospective cohort of older patients who were screened for dementia in 2000–2004 and were tracked for five years. Trajectories were identified with latent class growth analysis.

Subjects

3673 low-income persons age 65 or older without dementia at baseline.

Measures

Incident dementia diagnosis, comorbid conditions, dual eligibility, acute and long-term care use and payments based on Medicare and Medicaid claims, medical record systems, and administrative data.

Results

Three trajectories were identified based on dementia incidence and short and long-term NH use: (1) high incidence of dementia with heavy NH use (5% of the cohort) averaging $56,111/year ($36,361 Medicare, $19,749 Medicaid); (2) high incidence of dementia with little or no NH use (16% of the cohort) averaging $16,206/year ($14,644 Medicare, $1,562 Medicaid); and (3) low incidence of dementia and little or no NH use (79% of the cohort) averaging $8,475/year ($7,558 Medicare, $917 Medicaid).

Conclusions

Dementia and its interaction with NH utilization are major drivers of publicly financed acute and long-term care payments. Medical providers in accountable care organizations and other health care reform efforts must effectively manage dementia care across the care continuum if they are to be financially viable.

Keywords: dementia, nursing home, acute care, payment

Introduction

Efforts to reform the health care system and control costs must address the growing number of older people with dementia and their greatly increased risk of acute and long-term care. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has provisions for Accountable Care Organizations and special plans for persons dually-eligible for Medicare and Medicaid that are aimed at controlling costs through new financing arrangements (1). Persons with dementia are singled out in the ACA as a target group at risk for higher health care costs and in need of better care management. Dementia’s impact on nursing home (NH) use is well established: dementia is the strongest independent predictor of institutionalization (2, 3); the majority of persons with dementia will utilize nursing facility care prior to death (4, 5) and persons with dementia have higher nursing facility and total Medicaid payments (6). Dementia also leads to increased acute care payments including higher Medicare payments for inpatient, outpatient, and other acute care services (6–9).

While prior research has reported higher Medicaid or Medicare payments for older people with dementia, the interaction between dementia, long-term care, and acute care utilization has received limited attention. For example, does dementia increase the likelihood of acute care use and payments in both the community and NH settings? Kane and Atherly (10), in their study of Medicare beneficiaries during the 1990s, found that dementia was associated with 2.4 times higher Medicare Part A (inpatient) payments and 1.3 times higher Part B (outpatient) payments for persons living in the community. In contrast, among persons living in NHs the ratio of payments for persons without dementia were 0.7 for Part A and 0.9 for Part B payments. Prior studies of dementia and acute and long-term care costs have had methodological limitations. First, incident cases of dementia are often undetected in longitudinal studies when dementia is measured only at baseline or over a limited number of measurement points (10, 11). Second, prior research has not examined trajectories of NH use (3, 11). The main outcomes in prior studies have been “ever using a NH” or “time to first NH admission”. These studies have not examined patterns of NH use over time, nor have they distinguished between short stays, long stays, or a combination of the two. Third, few studies have had comprehensive and detailed measures of NH costs from both Medicare and Medicaid (7). Finally, many studies were carried out decades ago. Nursing homes are increasingly the source of Medicare post-acute or rehabilitative care, resulting in more short-term NH stays.

Previous analysis of the cohort in this study revealed a very high rate of transitions back and forth between settings (12). Persons with dementia had greater Medicare and Medicaid nursing facility use, greater hospital and home health use, and more transitions in care between acute and long-term care settings than those without dementia. The current study focuses on acute and long-term care use and payments. We hypothesized that dementia in combination with heavy NH use would result in substantially higher acute as well as long-term care payments. Our study objectives were as follows:

Identify classes of individuals with similar trajectories of incident dementia and overall NH use, including short and long NH stays, when modeled jointly over the 5-year period.

Determine factors such as age, gender and chronic disease diagnoses that are associated with different trajectories.

Compare the trajectories according to annual long-term care, acute care, and total payments from Medicare and Medicaid.

Methods

The Indiana University Purdue University-Indianapolis Institutional Review Board and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Privacy Board approved this study.

The study cohort consists of 3,673 primary care patients who were screened for cognitive impairment at the time of primary care appointments from May 2001 to June 2004 (13–15). No one in the cohort for the present study had dementia at baseline; persons screening positive or having a dementia diagnosis were excluded. Also, no one resided in a NH at the beginning of the study. Because this screening cohort anchored patients in time as community-based patients receiving primary care from the health care system studied, we were able to link these patients’ electronic medical record data with the additional databases described below.

The study site was Wishard Health Services, an urban public health system serving primarily low-income persons in Indianapolis. Wishard Health Services includes a 350-bed hospital and a network of eight primary care centers in Indianapolis. It has a Senior Care program staffed by faculty in an academic geriatric medicine program which includes services such as an Acute Care for Elders Unit, a physician house calls program, and specialty geriatric ambulatory care services.

We constructed a comprehensive longitudinal data set for the study cohort measuring their incident dementia, demographics and comorbidities, and long-term and acute care use and payments over a 5-year period following each patient’s index screening (12). We merged local electronic medical record data (16) with data from four additional databases from 2001–2008: Medicare claims; Indiana Medicaid claims; nursing home Minimum Data Set (MDS); and Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS) (17). Although the Wishard Health System is the site where patients were initially enrolled, the Medicare and Medicaid claims capture the patients’ utilization for any other provider or hospital. The MDS and OASIS data were used to corroborate nursing home and home health days in the claims data.

We identified incident cases of dementia based on International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes 290.0–290.43, 291.2, 294.0–294.9, 331.0–331.9, 333.0, and 797, consistent with our prior study (18). The onset date for dementia was defined by the first appearance of the code after enrollment in any of the linked datasets. Prior research relying on Medicaid claims had 84% specificity and 69% sensitivity in detecting incident dementia (18). We likely improved accuracy by identifying ICD code diagnoses from Medicaid, Medicare, MDS, OASIS, and local electronic medical record sources.

We used latent class growth curve analysis (LCGA) to model change over time in incident dementia and short and long NH stays. LCGA is a person-centered approach that identifies classes of individuals that are homogenous with respect to outcomes (19, 20). From a statistical standpoint the classes are assumed to represent different sub-populations having distinct growth patterns and outcome distributions. The overall pattern of outcomes observed in the data is assumed to be a mixture of distinct distributions. Mixture models have been applied to functional status, mental status, and health status trajectories of older persons (21–23).

Our LCGA model focused on three binary outcomes modeled jointly: incident dementia, short NH stays, and long NH stays in each year over the 5-year period. Short NH stays were < 90 days and long-stays were >= 90 days, beyond 90 days individuals are likely to remain in the NH permanently (24). Growth factors were estimated separately for incident dementia and short and long-term stays; however, the three processes were included in the model simultaneously. Each growth process was characterized with linear and quadratic terms to measure curvilinear change over time. A categorical latent class variable captured the different classes of patients having similar trajectories drawing on the outcomes of dementia status, short-and long-term NH use. We began by specifying a single class model and then expanded the model with additional classes. We evaluated model fit with Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) (25, 26), Lo-Mendel Rubin (LMR) test of k vs. k-1 classes (27), entropy and overall model interpretability and parsimony (28). Analysis was performed with MPlus software (29).

Second, we compared individuals having different trajectories according to their characteristics such as age, gender, race, Medicaid coverage, chronic disease comorbidities, and mortality, and their average annual Medicare and Medicaid payments for acute and long-term care services.

Finally, in order to determine the incremental increase in payments associated with different trajectories, we performed a multiple ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis, in which Medicare and total health care payments were regressed on trajectory coded as a dummy variable, while controlling for comorbidities and other covariates. Because payments were right-skewed we normalized the distribution by taking the natural log.

Results

Characteristics of the 3673 individuals in the study cohort are presented in the first column of Table 1. The majority of the cohort was female and African American, with an average age of 71. One-third was dually eligible at baseline, with 55% being Medicaid enrolled during the 5 years. These older adults suffer from a high prevalence of chronic conditions, and about one-fourth had died during the study. Dementia incidence was 5.5% in Year 1 and by Year 5 the cumulative incidence was 20.9%. Table 1 also presents information on use and payments for care. The overall sample averaged only 2.55 days of short or 5.69 days long-term NH care per year. The majority of their annual payments were for Medicare inpatient and outpatient acute care. Figures are based on individuals alive each year.

Table 1.

Individual Characteristics and Use and Payments for Care by Dementia and NH Use Trajectories (n=3673)

| Variable | Overall sample (n=3673) | TR1 Lo Dem & Lo/No NH Use (n=2902) | TR2 Hi Dem & Lo/No NH Use (n=573) | TR3 Hi Dem & Heavy NH Use (n=198) | p-value TR3 vs. TR2 | p-value TR3 vs. TR1 | p-value TR1 vs. TR2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics % or Mean (SD) | |||||||

| Age (mean, sd) | 71.4 (5.7) | 70.9 (5.4) | 73.5 (6.4) | 73.8 (6.5) | .5617 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Femalegender (%) | 69.4 | 68.8 | 70.5 | 74.8 | .2539 | .0802 | .4233 |

| African American (%) | 56.0 | 55.7 | 60.6 | 48.0 | .0020 | .0357 | .0304 |

| Dual eligible at baseline (%) | 33.8 | 31.9 | 38.4 | 48.5 | .0128 | <.0001 | .0025 |

| Dual eligible at any time (%) | 55.2 | 51.0 | 65.3 | 86.9 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Arthritis (%) | 68.8 | 66.8 | 75.0 | 80.3 | .1330 | <.0001 | .0001 |

| Cancer (%) | 46.6 | 44.9 | 54.6 | 48.5 | .1356 | .3216 | <.0001 |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 51.1 | 46.3 | 66.3 | 78.3 | .0016 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Congestive heart failure (%) | 43.4 | 37.9 | 59.2 | 78.8 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| COPD (%) | 45.5 | 42.1 | 53.8 | 71.7 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Diabetes (%) | 52.7 | 49.4 | 61.4 | 75.3 | .0004 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 95.5 | 94.7 | 98.1 | 98.5 | .7132 | .0192 | .0005 |

| Liver disease (%) | 16.9 | 14.9 | 24.4 | 24.2 | .9571 | .0004 | <.0001 |

| Renal disease (%) | 11.1 | 9.6 | 16.8 | 16.2 | .8469 | .0030 | <.0001 |

| Stroke (%) | 20.6 | 15.6 | 38.2 | 43.4 | .1958 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Died (%) | 25.9 | 21.0 | 39.1 | 59.1 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Dementia year 1 (%) | 5.5 | 0.0 | 24.4 | 31.8 | .0419 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Dementia year 2 (%) | 11.1 | 0.0 | 51.0 | 56.9 | .1589 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Dementia year 3 (%) | 14.9 | 0.0 | 74.3 | 68.8 | .1657 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Dementia year 4 (%) | 18.7 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 78.7 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Dementia year 5 (%) | 20.9 | 4.7 | 100.0 | 81.5 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Mean annual short term nursing home use and payments (SD) | |||||||

| Using care (%) | 6.30 | 3.57 | 7.29 | 43.40 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| NH days/year | 2.55 (9.50) | 1.22 (6.36) | 2.73 (6.12) | 21.51 (24.29) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Medicare payment ($) | 523.3 (1799.2) | 281.6 (1259.5) | 680.2 (1424.9) | 3610.9 (4535.1) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Medicaid payment ($) | 110.9 (832.0) | 40.4 (564.4) | 71.1 (462.8) | 1259.3 (2487.1) | <.0001 | <.0001 | .0086 |

| Mean annual long-termnursing home use and payments (SD) | |||||||

| Using care (%) | 2.74 | 0.20 | 0.56 | 46.25 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .0133 |

| NH days/year | 5.69 (29.9) | 0.28 (3.88) | 0.80 (5.34) | 99.03 (84.37) | <.0001 | <.0001 | .2518 |

| Medicare payment ($) | 173.9 (1066.4) | 17.4 (281.6) | 95.9 (659.3) | 2692.3 (3465.9) | <.0001 | <.0001 | .1010 |

| Medicaid payment ($) | 842.6 (5058.4) | 38.2 (696.1) | 70.6 (852.4) | 14867.6 (16084.8) | <.0001 | <.0001 | .1417 |

| Mean annual inpatient hospital use and payments (SD) | |||||||

| Using care (%) | 24.41 | 19.02 | 38.09 | 63.88 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| # of hospitalizations | 0.44 (0.76) | 0.31 (0.62) | 0.68 (0.77) | 1.53 (1.36) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| # of hospital days | 3.64 (8.73) | 2.41 (6.38) | 5.58 (10.36) | 16.06 (17.95) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Medicare payment ($) | 5385.8 (13843.1) | 3843.0 (11893.4) | 7887.9 (11682.4) | 20757.3 (28317.5) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Medicaid payment ($) | 139.8 (1664.9) | 113.4 (1346.6) | 131.7 (1912.5) | 549.9 (3763.4) | <.0001 | <.0001 | .7576 |

| Mean annual other acute payments (SD) | |||||||

| Using care (%) | 43.67 | 37.94 | 59.34 | 82.31 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Medicare payment ($) | 3381.0 (4675.5) | 2863.1 (4130.6) | 4712.5 (5916.5) | 7119.0 (5605.5) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Medicaid payment ($) | 750.2 (2333.3) | 594.9 (2221.2) | 1050.9 (2547.8) | 2155.8 (2715.1) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Mean annual other long-term care payments (SD) | |||||||

| Using care (%) | 14.30 | 10.45 | 25.23 | 39.07 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Medicare payment ($) | 751.9 (2507.1) | 552.6 (2451.4) | 1267.5 (2264.6) | 2182.1 (3218.2) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Medicaid payment ($) | 189.4 (1613.1) | 130.2 (1177.6) | 237.9 (1295.7) | 917.1 (4755.5) | .0007 | .0149 | .4217 |

| Mean annual Total payments (SD) | |||||||

| Medicare payment ($) | 10215.9 (18232.2) | 7557.6 (15063.5) | 14644.1 (16338.2) | 36361.6 (35090.4) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Medicaid payment ($) | 2033.0 (7021.2) | 917.1 (3400.1) | 1562.2 (3888.4) | 19749.8 (19242.3) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Total payment ($) | 12248.8 (20969.5) | 8474.8 (16174.8) | 16206.2 (17760.8) | 56111.4 (35193.0) | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

Notes:

Na – not applicable; Other Acute category includes ER, outpatient, and other costs; Other Long-termCare category includes home health, waiver and hospice costs.

TR1: low rate of dementia and little or no NH use; TR2: high rate of incident dementia with little or no NH use; and TR3: high rate of incident dementia with heavy NH use, both short and long stays.

The LCGA analysis yielded three classes of NH trajectories: (a) TR1 -- low rate of dementia and little or no NH use (79.0% of the sample), (b) TR2 -- high rate of incident dementia with little or no NH use (15.6%), and (c) TR3 -- high rate of incident dementia with heavy NH use (5.4%), both short and long stays. The two- and three-class solutions exhibited the best entropy (2-class .946, 3-class .946, 4-class .919 and 5-class .943). The LMR indicated a 4-class solution might fit the best (p-values for an additional class were: 2-class <.0001, 3-class .0001, 4-class <.0001 5-class .1580). BIC did not reach a minimum for the five fitted models (1-class 24,004, 2-class 16,764, 3-class 15,648, 4-class 15,135 and 5-class 14,785), but largest drop occurred with the 3-class model. The 3-class model had good fit overall and was the most parsimonious and readily interpretable.

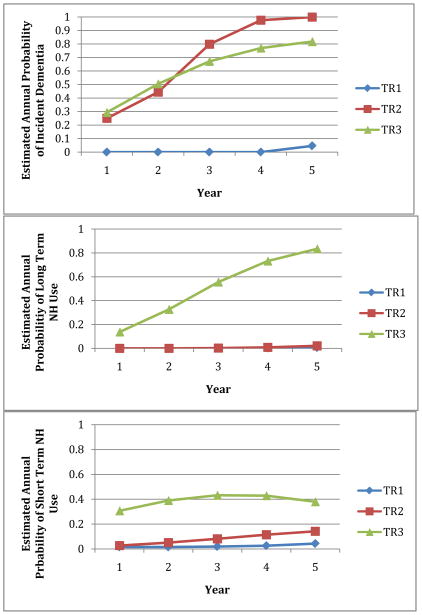

Figure 1 shows the growth curves over the 5-year period for the three trajectories in their incidence of dementia and long stay and short stay NH use. On an annual basis, individuals with the TR3 trajectory had a high probability of dementia (30–80%), and they has a high probability of a long (14–83%) or short (31–42%) NH stay. Individuals in TR 2 also had a very high probability of dementia (25–100%), but they had a low probability of a long (0–2%) or short (3–14%) NH stay. Individuals in TR1 had a very low probability of dementia (0–5%) combined with minimal probability of a long (< 1%) or short (2–4%) NH stay.

Figure 1.

Estimated Annual Probability of Incident Dementia and Long (>= 90 days) and Short (< 90 days) Nursing Home Stays by Trajectory

Note: TR1= low rate of dementia and little or no NH use; TR2= high rate of incident dementia with little or no NH use; and TR3= high rate of incident dementia with heavy NH use, both short and long stays.

The TR3 probability of long NH stays increases steadily over the 5-year period coinciding with rapidly increasing probability of dementia (Figure 1). The arc in short stay NH use for TR3 is likely a consequence of their increasing long stay NH use. Once they begin a long stay, NH residents are less likely to have a subsequent short stay. By year 3 the probability of persons in TR3 with a long stay is quite high, reducing the likelihood of a short stay.

Table 1, Columns 2–4 describes comorbid conditions and other characteristics for the three trajectories: low incident dementia and little/no NH use (TR1); high incident dementia and little/no NH use (TR2); and high incident dementia and heavy NH use (TR3). Compared to TR1, TR2 individuals were more likely to be older and dually eligible, to have coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, COPD, diabetes, or stroke, and to have died during the 5 years. When compared to TR2, TR3 individuals were even older, and more likely to be dually eligible, to have each of the comorbid conditions, and to have died during the 5 years. Also, when compared to the other two trajectories, individuals with TR3 were less likely to be African American or to have a cancer diagnosis. In a logistic regression analysis (Table 2) we identified significant independent predictors of an individual having a TR3 trajectory as opposed to a T2 trajectory (TR3=1/TR2=0). The model results were consistent with the bivariate relationships. The likelihood of having a heavy NH trajectory (TR3) was significantly greater for individuals who were dual eligible in Year 1, had a diagnosis of CHF, COPD, or diabetes, and died during the 5-year period. African Americans and individuals with cancer were less likely to have a TR3 trajectory. The C-statistic was a modest .709.

Table 2.

Odds ratios, 95% Confidence Intervals and P-values obtained from Logistic Regression Model for individuals having a TR3 (1) vs. TR2 (0) trajectory, N=771.

| Class 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

| Age | 1.02 | 0.99–1.04 | .3198 |

| Female | 1.09 | 0.73–1.64 | .6618 |

| Black | 0.57 | 0.40–0.82 | .0021 |

| Dual eligible at baseline | 1.47 | 1.04–2.09 | .0312 |

| Arthritis | 1.24 | 0.81–1.92 | .3233 |

| Cancer | 0.70 | 0.49–0.99 | .0486 |

| Coronary heart disease | 1.24 | 0.80–1.91 | .3319 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.72 | 1.11–2.69 | .0160 |

| COPD | 1.49 | 1.00–2.21 | .0475 |

| Diabetes | 1.68 | 1.13–2.51 | .0103 |

| Hypertension | 0.58 | 0.15–2.28 | .4331 |

| Liver disease | 0.92 | 0.61–1.39 | .6991 |

| Renal disease | 0.72 | 0.45–1.16 | .1738 |

| Stroke | 1.10 | 0.77–1.56 | .6104 |

| Died | 2.21 | 1.54–3.17 | <.0001 |

Notes:

TR2 (n=198) vs. TR2 (n=573). TR2 serves as the reference category. TR2: high rate of incident dementia with little or no NH use; and TR3: high rate of incident dementia with heavy NH use, both short and long stays.

The trajectories differed according to utilization and payments (Table 1). The TR3 trajectory, with high incidence dementia and heavy NH use, had significantly higher use of all forms of care compared to TR2, and TR2 had significantly higher use than TR1. Individuals with TR3 had predictably more short and long-term NH days and higher NH payments from both Medicaid and Medicare compared to the TR1 and TR2 trajectories. Individuals with the TR3 trajectory had substantially higher Medicare payments for inpatient hospital stays. They averaged $20,757/year compared to $7,888/approximately for persons with high incident dementia but low/no NH use (TR2) and $3,843 for persons with minimal dementia incidence and no/low NH use (TR1). With regard to other Medicare acute care payments (emergency department, outpatient, and other), individuals with the TR3 trajectory averaged $9,275 ($7,119 Medicare and $2,156 Medicaid). The TR2 trajectory averaged $5,763 ($4,713 Medicare and $1,051 Medicaid), and the TR1 trajectory averaged $3,458 ($2,863 Medicare and $595 Medicaid). For other long-term or home care payments from Medicaid and Medicare payments (home health, hospice, and home and community-based waivered service), individuals with the TR3 trajectory averaged $3,099 ($2,182 Medicare and $917 Medicaid), the TR2 trajectory averaged $1,505 ($1,268 Medicare and $238 Medicaid), and the TR1 trajectory averaged $683 ($553 Medicare and $130 Medicaid)

The TR3 trajectory averaged $36,361/year in total Medicare payments and $19,750 in total Medicaid payments, the latter coming primarily from NH use. In contrast, the TR2 trajectory averaged $14,644/year in total Medicare payments and $1,562/year in total Medicaid payments. TR1 trajectory was even lower, with $7,558/year for total Medicare payments and $917/year in total Medicaid payments.

The entire cohort averaged $45.0 Million in total Medicare and Medicaid payments per year. The dementia and heavy NH use trajectory (5% of the cohort) accounted for $11.1 Million or 25% of the total; the dementia and little/no NH use trajectory (16% of the cohort) accounted for $9.3 Million or 21% of the total; and the low dementia and little/no NH use trajectory (79% of the cohort) accounted for $24.6 Million or 55% of the total.

Finally, we tested two regression equations where the log of total Medicare and the log of total payments were regressed on the two high-dementia trajectories of TR2 and TR3 (TR1 serving as the reference category) and covariates. These regression models allowed us to estimate the incremental payment effects of the TR3 and TR2 trajectories when controlling for other factors that could contribute to higher payments. TR3 and TR2 trajectories were highly significant and positively related to the log of Medicare (Table 3) and the log of total annual payments (Table 4). Nearly all of the covariates were also statistically significant. Higher payments were associated with being female or dually eligible, having a diagnosis of arthritis, cancer, coronary artery disease, heart failure, stroke, COPD, diabetes, hypertension, liver disease, or kidney disease, and dying during the 5-year period. The R-square for the Medicare payment model was .481 and for the total payment model was .505. We took the exponent of the coefficients for the trajectory variables in order to estimate the percentage difference in adjusted payments between trajectories. Compared to the TR1 trajectory, TR2 had 53% greater Medicare payments and 193% greater total payments; TR3 had 56% greater Medicare and 364% greater total payments.

Table 3.

Multiple ordinary least squares (OLS) regression of log-transformed total Medicare payments, N=3460*.

| Variable | Unstandardized coefficient | Standard Error | t-value | p-value | Standardized coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR2 vs. TR1 | 0.43 | 0.05 | 8.08 | <.0001 | 0.11 |

| TR3 vs. TR1 | 1.08 | 0.08 | 12.68 | <.0001 | 0.17 |

| Age | −0.0001 | 0.003 | −0.03 | .9764 | −0.0004 |

| Female | 0.13 | 0.04 | 3.20 | .0014 | 0.04 |

| Black | −0.04 | 0.04 | −1.17 | .2409 | −0.01 |

| Dual eligible at baseline | 0.17 | 0.04 | 4.25 | <.0001 | 0.05 |

| Arthritis | 0.25 | 0.04 | 5.89 | <.0001 | 0.08 |

| Cancer | 0.42 | 0.04 | 11.23 | <.0001 | 0.14 |

| Coronary heart disease | 0.40 | 0.04 | 9.69 | <.0001 | 0.13 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.53 | 0.04 | 12.08 | <.0001 | 0.18 |

| COPD | 0.32 | 0.04 | 7.96 | <.0001 | 0.11 |

| Diabetes | 0.31 | 0.04 | 8.21 | <.0001 | 0.11 |

| Hypertension | 0.27 | 0.10 | 2.75 | .0060 | 0.03 |

| Liver disease | 0.29 | 0.05 | 5.76 | <.0001 | 0.07 |

| Renal disease | 0.34 | 0.06 | 5.73 | <.0001 | 0.07 |

| Stroke | 0.14 | 0.05 | 3.06 | .0022 | 0.04 |

| Died | 0.95 | 0.05 | 21.22 | <.0001 | 0.29 |

Notes:

Individuals with no payments were excluded from the model, R2 = .48.

TR1: low rate of dementia and little or no NH use; TR2: high rate of incident dementia with little or no NH use; and TR3: high rate of incident dementia with heavy NH use, both short and long stays.

Table 4.

Multiple ordinary least squares (OLS) regression of log-transformed total payments (Medicare + Medicaid), N=3532*.

| Variable | Unstandardized coefficient | Standard Error | t-value | p-value | Standardized coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR2 vs. TR1 | 0.45 | 0.05 | 8.47 | <.0001 | 0.11 |

| TR3 vs. TR1 | 1.53 | 0.08 | 18.32 | <.0001 | 0.23 |

| Age | −0.003 | 0.003 | −0.98 | .3290 | −0.01 |

| Female | 0.15 | 0.04 | 3.68 | .0002 | 0.05 |

| Black | −0.05 | 0.04 | −1.31 | .1898 | −0.01 |

| Dual eligible at baseline | 0.36 | 0.04 | 9.37 | <.0001 | 0.11 |

| Arthritis | 0.28 | 0.04 | 6.71 | <.0001 | 0.08 |

| Cancer | 0.43 | 0.04 | 11.47 | <.0001 | 0.14 |

| Coronary heart disease | 0.38 | 0.04 | 9.15 | <.0001 | 0.12 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.53 | 0.04 | 12.13 | <.0001 | 0.17 |

| COPD | 0.32 | 0.04 | 7.99 | <.0001 | 0.10 |

| Diabetes | 0.33 | 0.04 | 8.57 | <.0001 | 0.11 |

| Hypertension | 0.32 | 0.10 | 3.38 | .0007 | 0.04 |

| Liver disease | 0.26 | 0.05 | 5.35 | <.0001 | 0.07 |

| Renal disease | 0.33 | 0.06 | 5.57 | <.0001 | 0.07 |

| Stroke | 0.16 | 0.05 | 3.52 | .0004 | 0.04 |

| Died | 0.89 | 0.04 | 19.86 | <.0001 | 0.26 |

Notes:

Individuals with no payments were excluded from the model, R2 = .51.

TR1: low rate of dementia and little or no NH use; TR2: high rate of incident dementia with little or no NH use; and TR3: high rate of incident dementia with heavy NH use, both short and long stays.

Discussion

Dementia had a very strong and pervasive impact on annual payments from both Medicare and Medicaid for short and long-stay NH stays, acute care hospitalizations, and other long-term and acute care services. Its impact was heightened when combined with NH use. Dementia combined with heavy NH use resulted in 2.5 times greater Medicare and 12.6 times greater Medicaid annual payments compared to a trajectory of dementia with little of no NH use. And, dementia with heavy NH use resulted in 4.8 times greater Medicare and 21.5 times greater Medicaid annual payments compared to a trajectory of low incident dementia and little of no NH use. When taking comorbid conditions and other covariates into account, high incident dementia with little or no NH use resulted in total adjusted annual payments 193% greater than a trajectory with low incident dementia and little/no NH use. The percentage difference in adjusted payments for high incident dementia with heavy NH use was even more striking, this trajectory had 364% greater adjusted total payments than for low dementia and little or no NH use trajectory.

When compared to other trajectories, persons with dementia and heavy NH use were more likely to be white, to be dually eligible, to have chronic disease diagnoses, and to die during the 5-year period. Among individuals with incident dementia, comorbidities in combination with system factors (dual eligibility) and other factors (race) played a significant role in determining heavy NH use. Unmeasured system and social factors may very well have been further predictive of NH use and payments.

Our study has limitations. First, we did not have a functional measure of cognitive impairment that would allow us to assess dementia severity or stage. A person would be more likely to receive a formal dementia diagnosis after the disease had progressed, symptoms became more pronounced and they began using care. Second, we were not able to capture the private costs of dementia care, e.g., out-of-pocket expenses and family caregiving that can be substantial and would tend to be concentrated among persons with dementia in community settings (30). With this low-income population the primary private costs would probably in the form of family caregiving.

Findings from the study offer insights for the health care reform initiatives of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) (1). The study population, dual eligible and other low-income older persons receiving care in an urban health system, is an important target for projected Medicare and Medicaid cost savings because they are such heavy users of both acute and long-term care. The ACA encourages states to experiment with special needs plans or other models of integrated Medicaid and Medicare financing for the dually eligible (31). Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), another ACA initiative, are meant to incentivize provider groups to deliver better quality care at a lower cost through global budgeting and shared Medicare savings (32, 33). ACOs must enroll patients without regard to their health or cognitive status, or their history of acute or long-term care use. If they are to be financially viable, the ACOs and other reform initiatives must have a realistic understanding of their capacity to control costs, particularly if they experience adverse selection (34, 35). They need to assemble data and analyze their patient populations (36). The ACOs are likely to experience wide variation both within and between provider organizations in episodes of care and costs (37). Since ACOs and some special needs plans will be at financial risk only for Medicare expenses, the states should guard against cost shifting by carefully monitoring Medicaid expenses for dual eligibles enrolled in these plans.

We have shown in an earlier analysis that dementia patients’ acute and long-term care use is highly dynamic with multiple transitions between settings (12). Health systems and providers, if they are to deliver better care and control costs, will have to develop strategies to effectively manage services for dementia patients, particularly those patients who are at risk of becoming heavy users of NH care. These strategies should prevent patients with dementia from moving from low or no NH use to heavy NH use trajectories and thereby should decrease Medicaid costs. They should target heavy NH users (dementia and no dementia) for interventions to decrease hospital admissions and Medicare costs. They should target community dwelling patients with dementia for interventions aimed at decreasing hospital admissions and Medicare costs.

The ACOs and related medical/health care homes place a great deal of emphasis on primary care for better management of medically complex patients (38). Geriatricians and other primary care providers could play a critical role in the coordination of care for dementia patients. The ACA’s provision for cognitive screening of Medicare patients should alert medical providers to patients who are in the early stages of dementia. Collaborative care models based in primary care have been successful in improving care outcomes for dementia patients and other vulnerable elders without increasing health care costs (14, 39). Once a patient with dementia is at risk for NH care, whether short or long-term, the patient will need care management focused on both medical and social factors, across acute and long-term care. Interventions aimed at managing behavioral problems and shoring up family and other social resources are likely to be most effective (14). Social factors not measured in our study but likely to be critical to care and cost outcomes include poverty, resources for self-management, transportation, availability and skills of the family caregiver, and other community resources.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this paper was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under grant numbers R01 AG031222 and K24 AG024078. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.HealthCare.gov. [Accessed April 20, 2012];Compilation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. 2010. 2012 Available at: http://www.healthcare.gov/law/full/index.html.

- 2.Gaugler JE, Duval S, Anderson KA, et al. Predicting nursing home admission in the U. S: a meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luppa M, Luck T, Weyerer S, et al. Prediction of institutionalization in the elderly. A systematic review. Age Ageing. 2010;39:31–38. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welch HG, Walsh JS, Larson EB. The cost of institutional care in Alzheimer’s disease: nursing home and hospital use in a prospective cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:221–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith GE, O’Brien PC, Ivnik RJ, et al. Prospective analysis of risk factors for nursing home placement of dementia patients. Neurology. 2001;57:1467–1473. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.8.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou Y, Zhang K, Lin PJ, et al. A Longitudinal Analysis of the Lifetime Cost of Dementia. Health services research; 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oremus M, Aguilar SC. A systematic review to assess the policy-making relevance of dementia cost-of-illness studies in the US and Canada. PharmacoEconomics. 2011;29:141–156. doi: 10.2165/11539450-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao Y, Kuo TC, Weir S, et al. Healthcare costs and utilization for Medicare beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s. BMC health services research. 2008;8:108. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okie S. Confronting Alzheimer’s disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365:1069–1072. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1107288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kane RL, Atherly A. Medicare expenditures associated with Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2000;14:187–195. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200010000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaugler JE, Yu F, Krichbaum K, et al. Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Med Care. 2009;47:191–198. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818457ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Callahan CM, Arling G, Tu W, et al. Transitions in care among adults with and without dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03905.x. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schubert CC, Boustani M, Callahan CM, et al. Comorbidity profile of dementia patients in primary care: are they sicker? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:104–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2006;295:2148–2157. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boustani M, Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, et al. Implementing a screening and diagnosis program for dementia in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:572–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald CJ, Overhage JM, Tierney WM, et al. The Regenstrief Medical Record System: a quarter century experience. Int J Med Inform. 1999;54:225–253. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(99)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callahan CM, Weiner M, Counsell SR. Defining the Domain of Geriatric Medicine in an Urban Public Health System Affiliated with an Academic Medical Center. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1802–1806. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bharmal MF, Weiner M, Sands LP, et al. Impact of patient selection criteria on prevalence estimates and prevalence of diagnosed dementia in a Medicaid population. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21:92–100. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31805c0835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muthén BM, Muthén LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analysis: Growth mixture modeling with latenet trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCulloch CE, Lin H, Slate EH, et al. Discovering subpopulation structure with latent class mixed models. Statistics in medicine. 2002;21:417–429. doi: 10.1002/sim.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dodge HH, Du Y, Saxton JA, et al. Cognitive domains and trajectories of functional independence in nondemented elderly persons. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2006;61:1330–1337. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.12.1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Han L, et al. Trajectories of disability in the last year of life. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;362:1173–1180. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Han L, et al. Functional trajectories in older persons admitted to a nursing home with disability after an acute hospitalization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:195–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02107.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arling G, Kane RL, Cooke V, et al. Targeting residents for transitions from nursing home to community. Health services research. 2010;45:691–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLachlan GJ, Peel D. Finite Mixture Models. New York: Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lo Y, Mendell N, Rubin D. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88:767–778. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Celeux G, Soromendho G. An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Journal of Classification. 1996;13:195–212. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles CA: Muthén and Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bloom BS, de Pouvourville N, Straus WL. Cost of illness of Alzheimer’s disease: how useful are current estimates? Gerontologist. 2003;43:158–164. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grabowski DC. Special Needs Plans and the coordination of benefits and services for dual eligibles. Health affairs. 2009;28:136–146. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berwick DM. Making good on ACOs’ promise--the final rule for the Medicare shared savings program. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365:1753–1756. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1111671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berwick DM. Launching accountable care organizations--the proposed rule for the Medicare Shared Savings Program. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:e32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1103602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landon BE. Keeping score under a global payment system. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366:393–395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1112637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singer S, Shortell SM. Implementing accountable care organizations: ten potential mistakes and how to learn from them. Jama. 2011;306:758–759. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higgins A, Stewart K, Dawson K, et al. Early lessons from accountable care models in the private sector: partnerships between health plans and providers. Health affairs. 2011;30:1718–1727. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Brantes F, Rastogi A, Soerensen CM. Episode of care analysis reveals sources of variations in costs. The American journal of managed care. 2011;17:e383–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rittenhouse DR, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. Primary care and accountable care--two essential elements of delivery-system reform. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361:2301–2303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0909327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Tu W, et al. Cost analysis of the Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders care management intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1420–1426. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]