Abstract

Cysticercosis is a common tropical disease. One of the uncommon manifestations and a rare complication is its disseminated form (DCC). Neurocysticercosis (NCC) is the common parasitic disease of the central nervous system. Human cysticercosis is caused by the dissemination of the embryo of Taenia solium in the intestine via the hepatoportal system to the tissues and organs of the body. The organs most commonly affected are the subcutaneous tissues, skeletal muscles, lungs, brain, eyes, liver, and occasionally the heart, thyroid, and pancreas. Widespread dissemination of the cysticerci can result in the involvement of almost any organ in the body. We report here a case of a 36-year-old-male with disseminated cysticercosis. He visited our hospital with symptoms of multiple palpable nodules, dementia, and confusion. After the investigations he was diagnosed with disseminated cysticercosis involving the brain, subcutaneous tissues all over the body, and the skeletal muscles. The patient was initially treated with Albendazole in a private hospital, but there was no response. Then he was treated with Praziquantel and steroids.

KEYWORDS: Disseminated cysticercosis, Neurocysticercosis, cysticercosis

INTRODUCTION

Cysticercosis is caused by the Cysticercus cellulose, a larval form of the tape worm Taenia solium.

Humans acquire cysticercosis through fecal-oral contamination with T. solium eggs from tape worm carriers.

Disseminated cysticercosis (DCC) is an uncommon manifestation of this common disease.[1] Widespread dissemination of the cysticerci can result in the involvement of almost any organ in the body.

The main features of DCC include intractable epilepsy, dementia, and enlargement of the muscles, subcutaneous and lingual nodules, and a relative absence of focal neurological signs or obvious raised intracranial pressure, at least until late in the disease. Muscular pseudohypertrophy, a rare presentation, is caused by heavy infection of the skeletal muscles, which gives the patient a ‘Herculean appearance’. Fewer than 50 cases of DCC have been reported worldwide, the majority being from India. As cysticerci can be found anywhere in the body, their location and size determine the clinical presentation.[2] Here we report a case of DCC with diffuse involvement of the subcutaneous tissues, skeletal muscles, and brain.

CASE REPORT

A 36-year-old male was admitted to our hospital with complaints of multiple palpable nodular lesions all over the body, of a two-year duration, which gradually increased in number and size. He also complained of progressive loss of memory and judgment since six months. On clinical examination there were multiple palpable nodular lesions all over the body, predominantly seen over the back region, neck, chest, abdominal wall, forearms, and arms. They were varying in size from 0.5 to 4 cm and were well-defined. Venous prominence was clearly visible over the affected areas. Muscular pseudohypertrophy was also seen in the neck and arm region along with nodules [Figures 1 and 2]. On central nervous system (CNS) examination, the patient had mild-to-moderate deficit in attention, orientation, memory, and judgment.

Figure 1.

Clinical photograph showing multiple, subcutaneous, nodular lesions over the forearm

Figure 2.

Clinical photograph showing multiple nodular lesions over chest wall and abdomen

Routine hematological investigations showed hemoglobin to be 9.5 g/dl and the total leukocyte count (TLC) was within normal limits. The differential leukocyte count (DLC) showed borderline eosinophilia (7%).

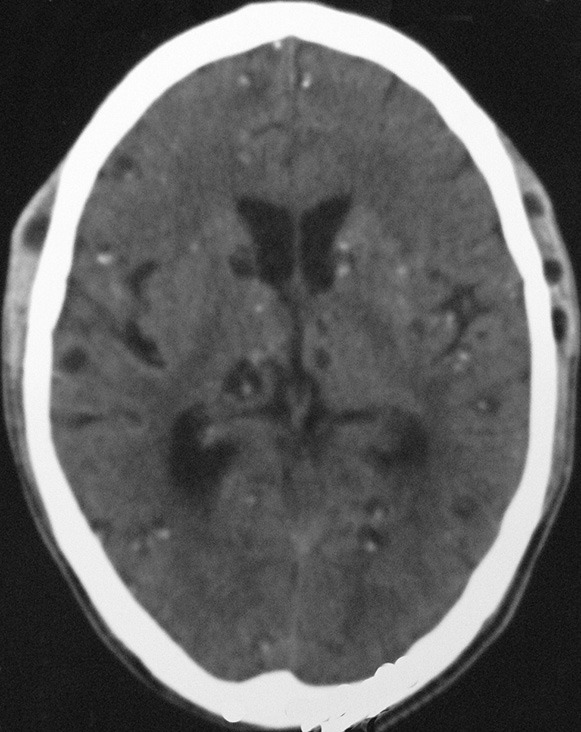

All other investigations were within normal limits. Computerized tomography (CT) scan of the brain showed multiple cystic lesions scattered throughout the brain parenchyma, with some showing eccentric calcified focus, suggestive of neurocysticercosis (scolex and calcified stage) [Figure 3]. The CT scan also showed involvement of the temporalis muscle, massetor muscle, the posterior neck muscles on both sides, and the superior oblique muscle on the left side. A chest X-ray showed a patch of pneumonitis on the right paracardiac region. The left lung and cardiophrenic angles were clear. An abdominal ultrasound showed no intra-abdominal lesion. Multiple small cystic lesions were seen in the subcutaneous planes. Excision of a single lesion on the forearm was done and sent for histopathology.

Figure 3.

CT scan of the brain showing multiple scattered lesions of cysticercosis throughout the brain parenchyma, with some showing eccentric calcification

PATHOLOGICAL FINDINGS

Gross

The specimen was received in the Department of Pathology. It was a single, grayish-white, cystic lesion, measuring 2 × 1.2 × 0.5 cm. The cut surface showed a cystic lesion containing clear watery fluid. It was a biloculated, thin-walled cyst, containing a tiny, white, solid area on the inner aspect, representing scolex [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

A biloculated, thin-walled cyst containing watery fluid and a tiny white area in the center

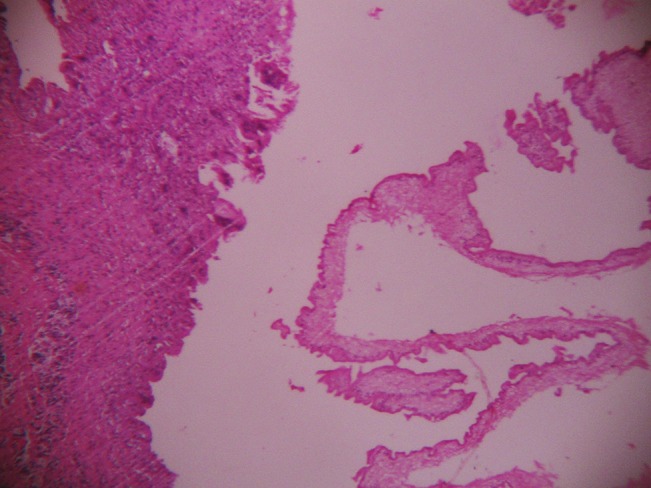

Microscopy

Sections of the cyst revealed the larva of Cysticercus, accompanied by a chronic inflammatory infiltrate and foreign-body, giant-cell reaction [Figure 5]. These histopathological findings confirmed that the cysts were of Cysticercus cellulose.

Figure 5.

Histopathology of a subcutaneous forearm nodule, showing encysted larva of the cysticercus surrounded by a chronic inflammatory infiltrate and giant-cell reaction (H and E, × 100)

Initially the patient was treated with Albendazole in a private hospital. However, there was no response. Subsequently, the patient was treated with tapering doses of prednisolone (1 mg/kg of body weight) one week prior to the initiation of Praziquantel therapy, instituted at a dose of 15 mg/kg/day. The symptoms improved. There was reduction in the number and size of the swellings. Praziquantel was continued for a total duration of 21 days. The patient was discharged after observation in the hospital. No side effects were observed. On follow-up, after five months, there was significant improvement in the patient.

DISCUSSION

Human cysticercosis is caused by the dissemination of the embryo of Tinea solium from the intestine via the hepatoportal system to the tissues and organs of the body. Ingested eggs pass into the bloodstream, disseminate into various organs, and form cysts, which characterize cysticercosis.[2,3] T. solium is present worldwide, but is most prevalent in Mexico, Africa, South-East Asia, Eastern Europe, and South America.[3]

Widespread dissemination of cysticerci throughout the human body was reported as early as 1912, by British Army medical officers stationed in India.[4] The organs most commonly affected are the subcutaneous tissues, skeletal muscles, lungs, brain, eyes, liver, and occasionally the heart. Widespread dissemination of the cysticerci can result in the involvement of almost any organ in the body. The clinical features depend upon the location of cysts, cyst burden, and a host reaction.[1]

Bandyopadhyay et al.,[5] have described a case of cysticercosis with marked pseudohypertrophy of the calf and shoulder muscles. Diagnosis of cysticercosis involving muscles is difficult clinically. Cysts that reside in the muscles are difficult to palpate, as they are often deep-seated; and numerous cysts lying side by side, intramuscularly, impart a smooth, shiny, and tense appearance to the muscles. Banu et al. have reported a case of disseminated cysticercosis that had diffuse involvement of the skeletal muscles, lungs, subcutaneous tissues, and brain. Despite diffuse involvement of multiple organs, the patient had presented with only arthritis.[6]

Computed tomography scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are useful in anatomical localization of the cysts. An MRI is more sensitive than a CT, as it identifies scolex and live cysts in cisternal spaces and ventricles and identifies the response to treatment.[1,2] Unenhanced CT scans of the muscles can show innumerable cysts standing out clearly against the background of the muscle mass in which they are embedded; the CT image appears like a honeycomb or leopard spots.[1]

The radiological findings of cysticercosis – a cystic lesion with a central nodule that represents the scolex – are very similar in all affected organs. On MRI, cysticercosis lesions appear hyperintense, with well-defined edges, which show a hypointense eccentric nodule within, representing the dead parasite's head, which is called the scolex. The presence of a scolex in a cystic lesion usually suggests the diagnosis of cysticercosis.[7]

Management of DCC includes symptomatic treatment of the central nervous system lesions using steroids and antiepileptics. In patients with raised intracranial tension, surgical removal of cysts and ventriculoperitoneal shunting can alleviate the symptoms. Pharmacological management with cysticidal drugs Praziquantel (10-15 mg/kg/day for 6-21 days) and Albendazole (15 mg/kg/day for 30 days) is indicated, as they help by reducing the parasite burden. These drugs hasten the death of the cysts, which may occur even in the absence of such treatment. Pharmacological treatment may be associated with severe reactions, which may result in enlargement of the cysts, massive release of antigens causing local tissue swelling, and a generalized anaphylactic reaction. Priming with corticosteroids before starting the cysticidal drug, decreases the incidence of such complications. There is no role for cysticidal drugs in inactive neurocysticercosis, that is, calcified cysts, as the parasites are dead.[2,6]

Cysticercosis with extensive involvement of the subcutaneous tissue all over the body, skeletal muscles and brain, is indeed very rare. In our case, failure to recognize symptoms of slowly progressive dementia and ignorance of the patient with regard to the association between nodular lesions and CNS disease may be the contributing factors for late presentation and widespread dissemination of the disease.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Kumar A, Bhagwani DK, Sharma RK, Kavita, Sharma S, Datar S, et al. Disseminated cysticercosis. Indian Pediatr. 1996;33:337–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhalla A, Sood A, Sachdev A, Varma V. Disseminated cysticercosis: A case report and review of literature. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:137. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jain BK, Sankhe SS, Agrawal MD, Naphade PS. Disseminated cysticercosis with pulmonary and cardiac involvement. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2010;20:310–3. doi: 10.4103/0971-3026.73532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishnaswami CS. Case of cysticercuscellulose. Ind Med Gaz. 1912;27:43–4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bandyopadhyay D, Sen S. Disseminated cysticercosis with muscle hypertrophy. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:49–51. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.48987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banu A, Veena N. A rare case of disseminated cysticercosis: Case report and review of literature. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2011;29:180–3. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.81787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Del Brutto OH, Rajshekhar V, White AC, Jr, Tsang VC, Nash TE, Takayanagui OM, et al. Proposed diagnosticcriteria for neurocysticercosis. Neurology. 2001;57:177–83. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]