Abstract

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) and transverse myelitis may occur coexistently in the pediatric population. This may be explained by a shared epitope between peripheral and central nervous system myelin. Coexistent transverse myelitis, myositis, and acute motor neuropathy in childhood have not been previously described. We describe a 14-year-old female patient with transverse myelitis, myositis, and GBS following Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. She presented with weakness and walking disability. Weakness progressed to involve all extremities and ultimately, she was unable to stand and sit. Based on the clinical findings, a presumptive diagnosis of myositis was made at an outside institution because of high serum creatine kinase level. The patient was referred to our institution for further investigation. Magnetic resonance imaging of spine revealed enhancing hyperintense lesions in the anterior cervicothoracic spinal cord. The electromyography revealed acute motor polyneuropathy. Serum M. pneumoniae IgM and IgG were positive indicating an acute infection. Repeated M. pneumoniae serology showed a significant increase in Mycoplasma IgG titer. The patient was given intravenous immunoglobulin for 2 days and clarithromycin for 2 weeks. She was able to walk without support after 2 weeks of hospitalization. This paper emphasizes the rarity of concomitant myositis, transverse myelitis, and GBS in children.

Keywords: Guillain Barré syndrome, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, myositis, transverse myelitis

Introduction

Transverse myelitis is an unusual inflammatory disease of the spinal cord. It results in loss of sensory and motor function below the level of injury. Acute transverse myelitis can occur as an isolated inflammatory disorder or as part of a multifocal central nervous system demyelinating disease such as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis or neuromyelitis optica. Transverse myelitis may also occur on a background of infections, vaccinations, vasculitis, and trauma.[1–3]

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is defined as an acute, areflexic, flaccid paralysis, which is classified into four subgroups including acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy, acute motor axonal neuropathy, and Miller-Fisher syndrome. GBS is usually due to multifocal inflammation of the spinal roots and peripheral nerves, especially, the myelin sheaths. The axons are often damaged as a secondary consequence of the inflammatory response. The cause of GBS is poorly understood. The favored hypothesis is that it is due to an autoimmune response directed against antigens in the peripheral nerves that is triggered by a preceding bacterial or viral infection.[4,5]

GBS and transverse myelitis can occur simultaneously in the pediatric population.[6] This may be explained by a shared epitope between the peripheral and central nervous system myelin. Simultaneous development of inflammatory disorders of the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system is generally considered to be uncommon and there have been a few number of cases of concomitant acute transverse myelitis and inflammatory peripheral neuropathy.[6,7]

Acute childhood myositis is a rare, self-limiting muscle disorder mainly affecting children of school age. Clinically, it is characterized by the sudden onset of calf pain and muscle tenderness, and a refusal to walk and/or difficulty in walking. Serum creatinine kinase is elevated in most cases. The clinical manifestations usually follow the initial phase of an acute upper respiratory tract illness, most frequently associated with viral diseases.[8]

According to our knowledge, there is only one described case of GBS and transverse myelitis in childhood due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection, but there is no described case of myositis, GBS and transverse myelitis due to M. pneumoniae infection.

Case Report

A 14-year-old female patient was admitted with numbness and weakness of the legs and the arms. She had 9 days history of back pain with gradual weakness and paresthesia of the arms. Weakness progressed to involve all extremities and ultimately she was unable to stand and sit. Ten days prior to the onset of her symptoms, she had upper respiratory tract infection. She had received no medications during the course of infection. Based on the clinical findings, a presumptive diagnosis of myositis was made at an outside institution because of high serum creatine kinase level (2190 U/L, normal 29–168). She had no history of intramuscular injection. The patient was referred to our institution for further investigation. There was no history of consanguinity and neurologic disease in the family. Physical and neurological examination revealed normal deep tendon reflexes. There were no pathological reflexes. Muscle strengths in proximal and distal muscles of upper and lower extremities were 3/5 and 4/5, respectively. She had no sensory level and there was no lateralizing neurologic deficit. She had no bladder and bowel dysfunction. Abdominal skin reflexes were normal. The remainder of the physical and neurological examination was normal.

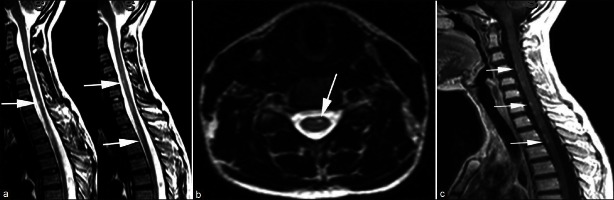

Laboratory examinations including blood count, renal, and liver function analyses, C-reactive protein, revealed no abnormality. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 28 mm/h (normal 0–20). Magnetic resonance imaging of brain was normal. Spine magnetic resonance imaging revealed hyperintense punctate lesions in the anterior cervicothoracic spinal cord, extending from C4 to T3 vertebral level on T2 weighted series. These lesions were enhancing on post-contrast series, which is consistent with disrupted spinal cord-blood barier [Figure 1]. Initial motor conduction studies on the 10th day of illness revealed a decrease in motor response amplitudes in bilateral median nerves and the left common peroneal nerve. The F response latency of bilateral tibial nerves was prolonged. Upper and lower extremity sensory responses were normal. The right median nerve conduction velocity was slow. The electromyography findings were consistent with mild acute motor polyneuropathy.

Figure 1.

T2 weighted sagital consecutive images (a) and transverse image (b) show hyperintense punctate lesions (arrows) in anterior of the cervicothoracic spinal cord, extending from C4 to T3 vertebral level. Contrast enhanced T1 weighted sagital image (c) shows enhancement of the lesions (arrows)

Neurologic, radiologic, and electromyographic findings suggested myositis, transverse myelitis, and GBS. Examination of the cerebrospinal fluid revealed normal protein and glucose levels with no pleocytosis. Cerebrospinal fluid polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was negative for adenovirus, varicella zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, and enterovirus. Cerebrospinal fluid culture showed no growth of any bacteria. Examination of cerebrospinal fluid revealed a normal IgG index (0.7; normal values 0.3–0.7). Isoelectrofocusing was negative for oligoclonal bands. Anti-nuclear antibodies and anti-double stranded deoxyribonucleic acid antibodies were negative. Complement levels (C3, C4) were normal. Serological work-up for toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, ebstein barr virus, brucella, salmonella, and hepatitis were negative. Serum M. pneumoniae IgM and IgG (85 RU/mL) were positive indicating an acute infection. M. pneumoniae serology was repeated 1 week after admission and showed an increase in M. pneumoniae IgG (148 RU/mL) titer. The case was considered as myositis, transverse myelitis, and GBS caused by M. pneumoniae infection.

The patient was treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (1 g/kg/day for 2 days) and clarithromycin (15 mg/kg/day). Clarithromycin was continued for 2 weeks. The patient′s complaints disappeared and strength improved over the following weeks.

On the 14th day of treatment, spinal magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated minimal regression in hyperintense signals. Repeated motor conduction studies revealed increase in motor response amplitudes. On 15th day of the follow-up, muscle strength was 4–5/5 in bilateral proximal upper and lower extremities. Her strength was 5/5 in the distal upper and lower extremities. She was discharged after starting to walk independently.

Discussion

Extrapulmonary manifestations of M. pneumoniae infection are common and involvement of every organ system has been reported.[2] Central and peripheral nervous system involvement is a frequent complication associated with M. pneumoniae infection. Neurological complications occur in 0.01–4.8% of M. pneumoniae infected patients.[2,9] M. pneumoniae induced neurological complications are well-described in children. The pathogenesis remains unclear, but is thought to be the result of direct invasion of the central nervous system, or a post-infectious immune-mediated response.[10,11] M. pneumoniae has been implicated in a number of immune mediated neurological diseases such as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis,[12] transverse myelitis,[13] and GBS.[14,15] Autoantibodies to brain antigens were first described by Biberfeld in patients with mycoplasma-induced central nervous system disease.[16] Since then, antibodies against galactocerebroside-C, GM1, GM2, Gt1b and GQ1b have been reported in some patients with M. Pneumoniae induced central nervous system dysfunction.[15,17–20] On the other hand, Biberfeld reported that M. Pneumoniae may have a direct activating effect on B cells.[21] Therefore, the important factor seems to be abnormal immune-mediated response to an infection rather than the direct effect of an infectious agent. On the other hand, a recent study explained pathogenesis of neurologic manifestations of M. pneumoniae infections by three mechanism including cytokine production, autoimmunity, and vascular occlusion.[22] Our patient developed central and peripheral nervous system disorder after 2 weeks of onset of respiratory symptoms. The spinal lesions and acute motor axonal polyneuropathy were considered to result from this autoimmune process. Another finding supporting autoimmune pathology is the marked clinical improvement after intravenous immunoglobulin.

Diagnosis and prognostic estimations of acute transverse myelitis have been done on the basis of clinical, electrophysiological and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Acute transverse myelitis is a rare complication of M. pneumoniae infection in childhood.[23] The long-term outcome of mycoplasma infection related transverse myelitis was reported to be favorable.[24] However, Csábi et al. reported that M. pneumoniae-induced acute transverse myelitis may lead to serious, life-long disability including paraplegia and bowel and bladder dysfunctions in childhood.[25] Generally, the prognosis of transverse myelitis has been reported to be better in children than in adults.[26] Defresne et al. evaluated 24 children with acute transverse myelitis, aged 2–14 years and reported that the outcome is favorable in 56% of patients. It is known that rapid onset of the deficit and severe weakness predict an unfavorable prognosis.[27] De Goede et al. evaluated the 2-year prospective results of transverse myelopathy in children. They reported that significant positive prognostic factors were preceding infection, start of recovery within a week of onset, age less than 10 years and lumbosacral spinal level on clinical assessment although significant negative predictors were flaccid legs at presentation, sphincter involvement, and rapid progression from onset to nadir within 24 h.[28] Our patient also had a history of upper respiratory infection 10 days prior to the onset of her symptoms. Our case showed slow clinical progression. The studies mentioned above led us to think that our patient′s prognosis will be favorable and her symptoms improved with treatment.

M. pneumoniae can be associated with myositis and rhabdomyolysis. In literature, there is a small number of case reports showing relationship between M. pneumoniae infection and myositis. Antibodies to smooth muscle have been detected in patients with M. pneumoniae infection. Although direct tissue invasion has been hypothesized, it has not been proved yet. The musculoskeletal involvement, polyarthralgia, and mild myalgia are common. Mycoplasma infection should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with myositis.[29–33] Rothstein et al. previously reported adult patient with cranial neuropathy, myeloradiculopathy, and myositis as the complications of M. pneumoniae infection.[31] Weng et al. noted 4-year-old boy with simultaneous onset of both acute rhabdomyolysis and transverse myelitis caused by infection of M. pneumoniae.[33] The high creatine kinase that was detected before her admission to our center was suggestive of M. pneumoniae-associated myositis.

Combined central and peripheral myelinopathy has been frequently reported in adults.[34–36] Nonetheless, coexistent transverse myelitis and acute motor axonal neuropathy in childhood was rarely described.[6,7,37] In one report, Howell et al. noted concomitant transverse myelitis and acute motor axonal neuropathy in 14-year-old boy presented with acute paraparesis with sensory and sphincter disturbance.[6] Etiology could not be determined in that case. To date; only one case with GBS and transverse myelitis in childhood caused by M. pneumoniae has been reported.[37] To the best of our knowledge, we report the first case of simultaneously myositis, acute motor polyneuropathy and transverse myelitis caused by M. pneumoniae in childhood.

Serologic diagnosis of M. pneumoniae infection requires collection of both acute-phase and convalescent phase serum samples and testing for both immunoglobulins IgM and IgG. It is necessary for optimum diagnosis of recent or current M. pneumoniae infection.[38] Increased M. pneumoniae immunoglobulin M titers have been demonstrated to be reliable markers of recent infection in children.[39] IgM antibodies rise shortly after the acute infection and may persist for 6 months. IgG antibodies increase within just a few weeks and also persist for several months.[40]

The isolation of M. pneumoniae from the cerebrospinal fluid or detection by the use of PCR are not common. Previous studies showed that the M. pneumoniae genome was detectable by PCR at a significantly higher rate in cerebrospinal fluid samples from patients with early-onset encephalitis than in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with late-onset encephalitis.[41–43] Serum M. pneumoniae IgM and IgG were detected positive in our patient. M. pneumoniae serology was repeated 1 week after admission and showed an increase in M. pneumoniae IgG titer. The isolation of M. pneumoniae in cerebrospinal fluid by PCR could not be performed due to the limited facilities of our laboratory. As a result, the high M. pneumoniae immunoglobulin M titers, the rise in M. pneumoniae IgG titer and preceding respiratory illness are highly suggestive of the diagnosis of M. pneumoniae-associated neurologic dysfunction.

The treatment of GBS with immunoglobulin is well established.[5] However, the treatment of mycoplasma infection related transverse myelitis has many treatment options. Immune-modulating therapies have been used alone or in combination including corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, and plasma exchange. In Mycoplasma-associated acute transverse myelitis, treatment with corticosteroids is recommended alone or together with immunoglobulin in case of probable or possibly severe clinical or radiological findings.[44] Antimicrobial treatment is controversial, due to low penetration via the blood-brain barrier, and potential immunologic mechanisms.[24] Previous studies implicated that cytokines were frequently increased in the central nervous system in patients with M. Pneumoniae infection.[22,43] In this respect, a recent study also revealed that macrolides have suppressive actions for these inflammatory cytokines in addition to their antimicrobial activity.[45] Our patient showed a dramatic improvement with intravenous immunoglobulin treatment requiring no additional corticosteroid treatment. Ýntravenous immunoglobulin was preferred because she had no diffuse involvement with edema of the spinal cord and had slow progression.

A unique feature in the present case is the simultaneous onset of myositis, GBS and transverse myelitis in a single patient subsequent to M. pneumoniae infection. In summary, M. pneumoniae-associated musculoskeletal, central and peripheral nervous system involvement may coexist in the pediatric population. Further research is necessary to better describe this entity and its prognosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the patient for her participation in this report.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Transverse Myelitis Consortium Working Group. Proposed diagnostic criteria and nosology of acute transverse myelitis. Neurology. 2002;59:499–505. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.4.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koskiniemi M. CNS manifestations associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections: Summary of cases at the University of Helsinki and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17(Suppl 1):S52–7. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.Supplement_1.S52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith R, Eviatar L. Neurologic manifestations of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections: Diverse spectrum of diseases. A report of six cases and review of the literature. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2000;39:195–201. doi: 10.1177/000992280003900401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes RA, Cornblath DR. Guillain-Barré syndrome. Lancet. 2005;366:1653–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67665-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ryan MM. Guillain-Barré syndrome in childhood. J Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41:237–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2005.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Howell KB, Wanigasinghe J, Leventer RJ, Ryan MM. Concomitant transverse myelitis and acute motor axonal neuropathy in an adolescent. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;37:378–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernard G, Riou E, Rosenblatt B, Dilenge ME, Poulin C. Simultaneous Guillain-Barré syndrome and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in the pediatric population. J Child Neurol. 2008;23:752–7. doi: 10.1177/0883073808314360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mall S, Buchholz U, Tibussek D, Jurke A, An der Heiden M, Diedrich S, et al. A large outbreak of influenza B-associated benign acute childhood myositis in Germany, 2007/2008. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30:e142–6. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318217e356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pönkä A. Central nervous system manifestations associated with serologically verified Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Scand J Infect Dis. 1980;12:175–84. doi: 10.3109/inf.1980.12.issue-3.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bitnun A, Ford-Jones E, Blaser S, Richardson S. Mycoplasma pneumoniae ecephalitis. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2003;14:96–107. doi: 10.1053/spid.2003.127226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Candler PM, Dale RC. Three cases of central nervous system complications associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;31:133–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riedel K, Kempf VA, Bechtold A, Klimmer M. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in an adolescent. Infection. 2001;29:240–2. doi: 10.1007/s15010-001-1173-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mills RW, Schoolfield L. Acute transverse myelitis associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection: A case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:228–31. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199203000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nadkarni N, Lisak RP. Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) with bilateral optic neuritis and central white matter disease. Neurology. 1993;43:842–3. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.4.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kusunoki S, Shiina M, Kanazawa I. Anti-Gal-C antibodies in GBS subsequent to mycoplasma infection: Evidence of molecular mimicry. Neurology. 2001;57:736–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.4.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biberfeld G. Antibodies to brain and other tissues in cases of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1971;8:319–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumada S, Kusaka H, Okaniwa M, Kobayashi O, Kusunoki S. Encephalomyelitis subsequent to mycoplasma infection with elevated serum anti-Gal C antibody. Pediatr Neurol. 1997;16:241–4. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(97)89976-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishimura M, Saida T, Kuroki S, Kawabata T, Obayashi H, Saida K, et al. Post-infectious encephalitis with anti-galactocerebroside antibody subsequent to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. J Neurol Sci. 1996;140:91–5. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(96)00106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komatsu H, Kuroki S, Shimizu Y, Takada H, Takeuchi Y. Mycoplasma pneumoniae meningoencephalitis and cerebellitis with antiganglioside antibodies. Pediatr Neurol. 1998;18:160–4. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(97)00138-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kikuchi M, Tagawa Y, Iwamoto H, Hoshino H, Yuki N. Bickerstaff's brainstem encephalitis associated with IgG anti-GQ1b antibody subsequent to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection: Favorable response to immunoadsorption therapy. J Child Neurol. 1997;12:403–5. doi: 10.1177/088307389701200612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biberfeld G, Arneborn P, Forsgren M, von Stedingk LV, Blomqvist S. Non-specific polyclonal antibody response induced by Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Yale J Biol Med. 1983;56:639–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Narita M. Pathogenesis of neurologic manifestations of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;41:159–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacFarlane PI, Miller V. Transverse myelitis associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Arch Dis Child. 1984;59:80–2. doi: 10.1136/adc.59.1.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goebels N, Helmchen C, Abele-Horn M, Gasser T, Pfister HW. Extensive myelitis associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection: Magnetic resonance imaging and clinical long-term follow-up. J Neurol. 2001;248:204–8. doi: 10.1007/s004150170227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Csábi G, Komáromy H, Hollódy K. Transverse myelitis as a rare, serious complication of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;41:312–3. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunne K, Hopkins IJ, Shield LK. Acute transverse myelopathy in childhood. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1986;28:198–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1986.tb03855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Defresne P, Hollenberg H, Husson B, Tabarki B, Landrieu P, Huault G, et al. Acute transverse myelitis in children: Clinical course and prognostic factors. J Child Neurol. 2003;18:401–6. doi: 10.1177/08830738030180060601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Goede CG, Holmes EM, Pike MG. Acquired transverse myelopathy in children in the United Kingdom – A 2 year prospective study. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2010;14:479–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunner J, Jost W. Myositis caused by a mycoplasma infection. Klin Padiatr. 2000;212:129–30. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bennett MR, O’Connor HJ, Neuberger JM, Elias E. Acute polymyositis in an adult associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Postgrad Med J. 1990;66:47–8. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.66.771.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rothstein TL, Kenny GE. Cranial neuropathy, myeloradiculopathy, and myositis: Complications of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Arch Neurol. 1979;36:476–7. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1979.00500440046007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belardi C, Roberge R, Kelly M, Serbin S. Myalgia cruris epidemica (benign acute childhood myositis) associated with a Mycoplasma pneumonia infection. Ann Emerg Med. 1987;16:579–81. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(87)80692-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weng WC, Peng SS, Wang SB, Chou YT, Lee WT. Mycoplasma pneumoniae - Associated transverse myelitis and rhabdomyolysis. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;40:128–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schulze Beerhorst K, Klein B, Oelerich M, Rieke K. The rare coincidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome and myelitis. Nervenarzt. 2007;78:445–50. doi: 10.1007/s00115-007-2254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katchanov J, Lünemann JD, Masuhr F, Becker D, Ahmadi M, Bösel J, et al. Acute combined central and peripheral inflammatory demyelination. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1784–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.037572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bajaj NP, Rose P, Clifford-Jones R, Hughes PJ. Acute transverse myelitis and Guillain-Barré overlap syndrome with serological evidence for mumps viraemia. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;104:239–42. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2001.00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonastre-Blanco E, Jordán-García Y, Fons-Estupiñá MC, Medina-Cantillo J, Palomeque-Rico A. Plasmapheresis in a paediatric patient with transverse myelitis and Guillain-Barre syndrome secondary to infection by Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Rev Neurol. 2011;53:443–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waites KB, Talkington DF. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and its role as a human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:697–728. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.4.697-728.2004. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waris ME, Toikka P, Saarinen T, Nikkari S, Meurman O, Vainionpää R, et al. Diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3155–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.11.3155-3159.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsiodras S, Kelesidis T, Kelesidis I, Voumbourakis K, Giamarellou H. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-associated myelitis: A comprehensive review. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:112–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kasahara I, Otsubo Y, Yanase T, Oshima H, Ichimaru H, Nakamura M. Isolation and characterization of Mycoplasma pneumoniae from cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with pneumonia and meningoencephalitis. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:823–5. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.4.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tjhie JH, van de Putte EM, Haasnoot K, van den Brule AJ, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM. Fatal encephalitis caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae in a 9-year-old girl. Scand J Infect Dis. 1997;29:424–5. doi: 10.3109/00365549709011844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Narita M, Itakura O, Matsuzono Y, Togashi T. Analysis of mycoplasmal central nervous system involvement by polymerase chain reaction. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:236–7. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199503000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yiş U, Kurul SH, Cakmakçi H, Dirik E. Mycoplasma pneumoniae: Nervous system complications in childhood and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:973–8. doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0714-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Labro MT. Anti-inflammatory activity of macrolides: A new therapeutic potential? J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41(Suppl B):37–46. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.suppl_2.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]