Dear Sir,

Infantile tremor syndrome (ITS) is a clinical disorder characterized by coarse tremors, anemia and regression of motor and mental milestones in children presenting at about 1 year of age.[1] Few reports of neuroimaging abnormalities in children with ITS are present. Most common finding of neuroimaging in ITS is cerebral atrophy with ex-vacuo enlargement of ventricles and subarachnoid space.[1–3] We did not find any report of subdural effusion in ITS.

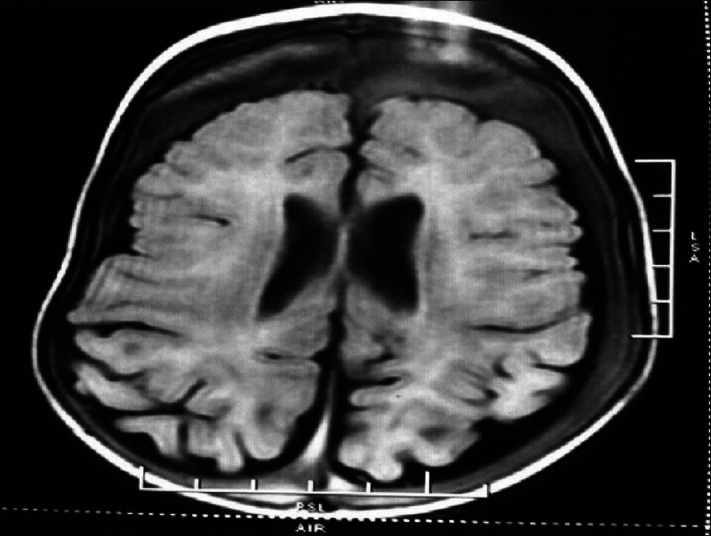

An 11-month old boy presented with pallor for 1 month, tremors of hands and feet for 2 days and delayed development. There was no history suggestive of fever, bleeding, rash, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice or seizures. The child was born at term gestation with no antenatal, natal or postnatal complications. Child was exclusively breast fed till 5 months of age and then received diluted cow′s milk in addition to breast feeding. Child weighed 5.5 Kg (weight for age = 58.5%), had a length of 66 cm (length for age 88%) and head circumference of 43.5 cm (between −2 SD and −1 SD). On physical examination, child had sparse hair, pallor and hyperpigmented knuckles. There were coarse tremors in all four limbs, perioral and periorbital region in awake as well as sleep state. Tremors were less in sleep stage. There was increased tone in all 4 limbs, but no paresis of limbs or cranial nerve palsies. There was no fracture or bruise. Developmental age was 5 months. Investigations revealed anemia (haemoglobin = 9.6 g%), mean corpuscular volume (MCV) (101.7 fl), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) (38 pg), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) (37.4%), with normal leucocyte count (11,400/mm3) and platelets (4 lakh/mm3). Peripheral smear suggested dimorphic anemia. Serum B12 level was 512 pg/ml (200–900 pg/ml) and serum folic acid was16.3 ng/ml (5–21 ng/ml). Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination revealed no red blood cells (RBCs) or neutrophils, normal protein, sugar and sterile cultures. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain revealed cerebral atrophy with paucity of white matter and ex-vacuo enlargement of ventricles and subarachnoid space. Subdural effusion was seen over all areas of brain [Figure 1]. Child was diagnosed as ITS. He received propranolol, carbamazepine, B12, magnesium and multivitamins. A dramatic response after 7 days was observed as appetite improved, tremors disappeared during sleep and decreased in amplitude in awake state. After 1 month of follow-up the child is active, gaining weight (6 kg), hemoglobin (12.4 g%) and tremors stopped. After 2 months of follow-up, tone has returned to normal and is achieving newer milestones (developmental age = 7 months). Propanol and carbamazepine has been tapered and stopped.

Figure 1.

T1-image in magnetic resonance imaging showing cerebral atrophy with white matter paucity, ex-vacou enlargement of ventricles and subarachnoid space and massive subdural effusion over all areas of brain

Deficiencies of Vitamin B12, iron, magnesium, zinc, copper, selenium and virus infections have been postulated as causative agents in ITS.[1,4–6] Only few reports of neuroimaging in ITS are available.[2,3,7,8] Most reports have shown normal neuroimaging findings or cerebral atrophy, ventricular prominence and/or prominence of subarachnoid space, pontine myelinolysis, cerebral hyperintensities[2,3,8] [Table 1]. In our case, MRI showed cerebral atrophy, white matter paucity with ex-vacuo enlargement of ventricles and subarachnoid space. Subdural effusion was present over all areas of brain. To our best knowledge, subdural effusion has not been reported in ITS in the past. The flair image [Figure 1]of MRI clearly shows a subdural effusion in addition to subarachanoid fluid. Subdural effusion in children may occur as a complication of meningitis or secondary to lysis in an old subdural hemorrhage. There was no history of fever, trauma or findings suggestive of battered baby in our case. Subdural effusion has also been seen in inborn errors of metabolism like menke′s kinky hair disease and glutaricaciduria. Developmental gain, cessation of tremors and absence of any neurological sequel suggest ITS as probable etiology of subdural effusion and an alternative diagnosis has not been missed. We conclude that subdural effusion, if found in ITS, may receive a trial of management for ITS, before being subjected to extensive investigations for inborn errors of metabolism.

Table 1.

Neuroimaging abnormalities reported in children with infantile tremor syndrome

References

- 1.Gupte S. The Short Textbook of Pediatrics. 8th. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers; 1998. Infantile tremor syndrome; pp. 558–61. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thora S, Mehta N. Cranial neuroimaging in infantile tremor syndrome (ITS) Indian Pediatr. 2007;44:218–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murali MV, Sharma PP, Koul PB, Gupta P. Carbamazepine therapy for infantile tremor syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 1993;30:72–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arya LS, Singh M, Aram GN, Farahmand S. Infantile tremor syndrome. Indian J Pediatr. 1988;55:913–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02727826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pohowalla JN, Kaul KK, Bhandari NR, Singh SD. Infantile “meningo-encephalitic” syndrome. Indian J Pediatr. 1960;27:49–54. doi: 10.1007/BF02896818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajpai PC, Misra PK, Tandon PN, Wahal KM, Newton G. Brain biopsy in infantile tremor syndrome. Indian J Med Res. 1971;59:413–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Datta K, Datta S, Dutta I. Rare association of central pontine myelinolysis with infantile tremor syndrome. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012;15:48–50. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.93279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ratageri VH, Shepur TA, Patil MM, Hakeem MA. Scurvy in infantile tremor syndrome. Indian J Pediatr. 2005;72:883–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02731123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]