Abstract

Background:

Membranous expression of the anti-adhesive glycoprotein podocalyxin-like (PODXL) has previously been found to correlate with poor prognosis in several major cancer forms. Here we examined the prognostic impact of PODXL expression in urothelial bladder cancer.

Methods:

Immunohistochemical PODXL expression was examined in tissue microarrays with tumours from two independent cohorts of patients with urothelial bladder cancer: n=100 (Cohort I) and n=343 (Cohort II). The impact of PODXL expression on disease-specific survival (DSS; Cohort II), 5-year overall survival (OS; both cohorts) and 2-year progression-free survival (PFS; Cohort II) was assessed.

Results:

Membranous PODXL expression was significantly associated with more advanced tumour (T) stage and high-grade tumours in both cohorts, and a significantly reduced 5-year OS (unadjusted HR=2.25 in Cohort I and 3.10 in Cohort II, adjusted HR=2.05 in Cohort I and 2.18 in Cohort II) and DSS (unadjusted HR=4.36, adjusted HR=2.70). In patients with Ta and T1 tumours, membranous PODXL expression was an independent predictor of a reduced 2-year PFS (unadjusted HR=6.19, adjusted HR=4.60) and DSS (unadjusted HR=8.34, adjusted HR=7.16).

Conclusion:

Membranous PODXL expression is an independent risk factor for progressive disease and death in patients with urothelial bladder cancer.

Keywords: podocalyxin-like protein, urothelial bladder cancer, prognosis

Although the majority of bladder malignancies do not invade muscle at diagnosis, their highly unpredictable potential for recurrence and progression into muscle invasion constitutes a significant clinical problem (Raghavan et al, 1990; Masood et al, 2004). High-grade bladder tumours with lamina propria invasion (T1) represent those at greatest risk, rendering surgical management of this disease subject to much controversy (Masood et al, 2004). Hence, there is a great need for novel prognostic biomarkers to identify bladder cancer patients who are more likely to fail first-line treatment, and who should be offered cystectomy as a primary treatment.

Tumours invading the muscularis propria (T2) and beyond (T3–T4) have high recurrence rates and poor prognosis (Soloway et al, 1994; Sternberg, 1995), and although several chemotherapeutic agents have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of advanced bladder cancer, response rates still need to be improved.

Podocalyxin-like protein (PODXL) is a glycoprotein with anti-adhesive properties, first identified as being the predominant sialoprotein expressed on the apical surface of the glomerular epithelium (Kerjaschki et al, 1984). The glycoprotein PODXL is also expressed in vascular endothelium (Kerjaschki et al, 1984) and haematopoietic stem cells (McNagny et al, 1997). The first report of PODXL expression in malignant cells was its description as a stem cell marker in testicular cancer (Schopperle et al, 2003). Since then, tumour-cell-specific PODXL expression has been found to associate with a more aggressive tumour phenotype and adverse outcome in several forms of cancer, for example, breast (Somasiri et al, 2004), prostate (Casey et al, 2006), ovarian (Cipollone et al, 2012), colorectal (Larsson et al, 2011; Larsson et al, 2012b) and pancreatic cancer (Dallas et al, 2012). In particular, the poor prognosis seems to be conferred by PODXL expression on the apical surface/membrane of tumour cells (Larsson et al, 2011; Cipollone et al, 2012; Dallas et al, 2012; Larsson et al, 2012b). In hepatocellular carcinoma, however, PODXL expression in the tumour-associated neovasculature has been demonstrated to correlate with poor prognosis (Heukamp et al, 2006).

The expression and prognostic implications of PODXL in urothelial bladder cancer has, to our knowledge, not yet been described. The aim of the present study was therefore to examine the associations of tumour-specific PODXL expression with clinicopathological factors, disease progression and survival in two independent cohorts of patients with urothelial bladder cancer (Cohort I (n=100) and Cohort II (n=343)).

Materials and Methods

Patients

Cohort I

This cohort is a consecutive cohort of all patients with a first diagnosis of urothelial bladder cancer in the Department of Pathology, Skåne University Hospital, Malmö, from 1 October 2002 until 31 December 2003, for whom archival tumour specimens could be retrieved (n=110). The cohort includes 80 (72.7%) men and 30 (27.3%) women with a median age of 72.86 (39.25–89.87) years. Information on vital status was obtained from the Swedish Cause of Death Registry up until 31 December 2010. Follow-up started at the date of diagnosis and ended at death, emigration or on 31 December 2010, whichever came first. Median follow-up time was 5.92 years (range 0.03–8.21) for the full cohort and 7.71 years (range 7.04–8.21) for patients alive at 31 December 2010 (n=48). Forty-eight patients (43.6%) died within 5 years.

The distribution of T-stage was 48 (43.6%) pTa, 24 (21.8%) pT1, 37 (33.8) pT2 and 1 (0.9%) pT3. Eighteen (16.4%) tumours were Grade I, 34 (30.9%) were Grade II and 58 (52.7%) were Grade III. Permission for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee at Lund University.

Cohort II

This cohort includes 344 patients from a prospective cohort of patients with newly diagnosed urothelial bladder cancer at the Uppsala University Hospital, from 1984 up until 2005. Tumour specimens have been collected retrospectively and the predominant group of pTa tumours reduced to include 115 cases. Patient and tumour characteristics are described in Supplementary Table 1. Progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) were calculated from the date of surgery to date of event or last follow-up. Progression was defined as shift of the tumour into a higher stage. Median time to progression for patients with non-muscle-invasive disease was 18 months (range 2–55). Follow-up time for non-recurrent and non-progressing cases were ⩾4 and ⩾5 years, respectively. Permission for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee at Uppsala University.

Tissue microarray construction

All tumours were histopathologically re-evaluated and classified according to the WHO grading system of 2004 by a board-certified pathologist. Tissue microarrays (TMAs) were constructed using a semi-automated arraying device (TMArrayer, Pathology Devices, Westminister, MD, USA). All tumour samples were represented in duplicate tissue cores (1 mm).

Immunohistochemistry and staining evaluation

For immunohistochemical analysis, 4-μm TMA sections were automatically pre-treated using the PT Link system and then stained in an Autostainer Plus (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Cohort I was used as a test cohort for comparison of three different antibodies targeting PODXL: one polyclonal, monospecific antibody (HPA002110; Atlas Antibodies AB, Stockholm, Sweden) diluted 1 : 250, which has been used and validated in previous biomarker studies on, for example, testicular, colorectal and pancreatic cancer (Cheung et al, 2011; Larsson et al, 2011; Dallas et al, 2012; Larsson et al, 2012b), and two monoclonal antibodies, clone 4F10 (sc-23903; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA), diluted 1 : 250, and clone CL0308 (AMAb90667, Atlas Antibodies AB), diluted 1: 250. Two of the antibodies, HPA002110 and CL0308, bind to epitopes within the extracellular domain of PODXL (Supplementary Figure 1A), whereas the epitope specificity for 4F10 is unknown. The specificities of HPA002110 and CL0308 were further validated using western blot analysis of PODXL-overexpressing cell line lysates (Supplementary Figure 1B). The results demonstrate that the two antibodies bind PODXL with identical specificity.

The TMA sections with tumours from Cohort II were stained with the polyclonal antibody HPA002110 (Atlas Antibodies AB).

The expression of PODXL was recorded as negative (0), weak cytoplasmic positivity in any proportion of cells (1), moderate cytoplasmic positivity in any proportion (2), distinct membranous positivity in ⩽50% of cells (3) and distinct membranous positivity in >50% of cells (4) as previously described (Larsson et al, 2011; Larsson et al, 2012b). Staining of PODXL was evaluated by two independent observers (KB and AHL) who were blinded to clinical and outcome data.

Epitope mapping

Peptide mapping of HPA002110 and CL0308 was essentially performed as described previously (Hjelm et al, 2011). Biotinylated synthetic peptides (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), 15 amino acids long with a 10- amino acid overlap, were designed to cover the entire PODXL antigen sequence. Peptides were dissolved and diluted to 0.1 mg ml−1 in PBS supplemented with BSA. Peptides were coupled to neutravidin-coated Bioplex COOH beads (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), and a bead mixture containing all 26 bead IDs was created. Antibodies were diluted to 200 ng ml−1 and mixed with 30 μl of bead mix, corresponding to 1200 beads per ID. The antibody–bead mix was incubated for 60 min, washed and mixed with PE-labelled anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG antibody, incubated 30 min, and then washed and analysed using a Bioplex 200 system according to the system manual.

Western blot

Two microgram of lysate from HEK293 cells expressing recombinant myc-DDK-PODXL (LY401657; Origene Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA) or the same amount of an empty-vector-transfected HEK293 cell control lysate (LY40001) were separated on precast 4–20% CriterionTGX SDS–PAGE gradient gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) under reducing conditions, followed by blotting to PVDF membranes (Immobilon-P; Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Membranes were blocked (5% dry milk, 0.5% Tween20, 1 × TBS) for 45 min at RT before addition of anti-PODXL antibody (HPA002110 and AMAb90667, clone CL0308, both from Atlas Antibodies AB) diluted 1 : 500 in blocking buffer. Following incubation for 1 h with the primary antibody, the membranes were washed 4 × 5 min in 1 × TBS with 0.1% Tween20. HRP-conjugated antibodies (Dako), diluted 1 : 3000 in blocking buffer, were added to the membranes and incubated for 1 h, followed by a final round of washing. Detection was carried out using Chemiluminescence HRP Substrate (Immobilon) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistics

Spearman's ρ- and χ2-tests were applied for analysis of the correlation between PODXL expression and clinicopathological characteristics. Kaplan–Meier analysis and log-rank test were used to illustrate differences in PFS (Cohort II), DSS (Cohort II) and 5-year OS (Cohort I and II) in strata according to PODXL expression. Cox regression proportional hazards modelling was used to estimate the impact of membranous vs non-membranous PODXL expression on PFS, DSS and 5-year OS in both univariable and multivariable analysis, adjusted for age, sex, T-stage and grade. All tests were two-sided. A P-value of 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Antibody validation and distribution of PODXL expression

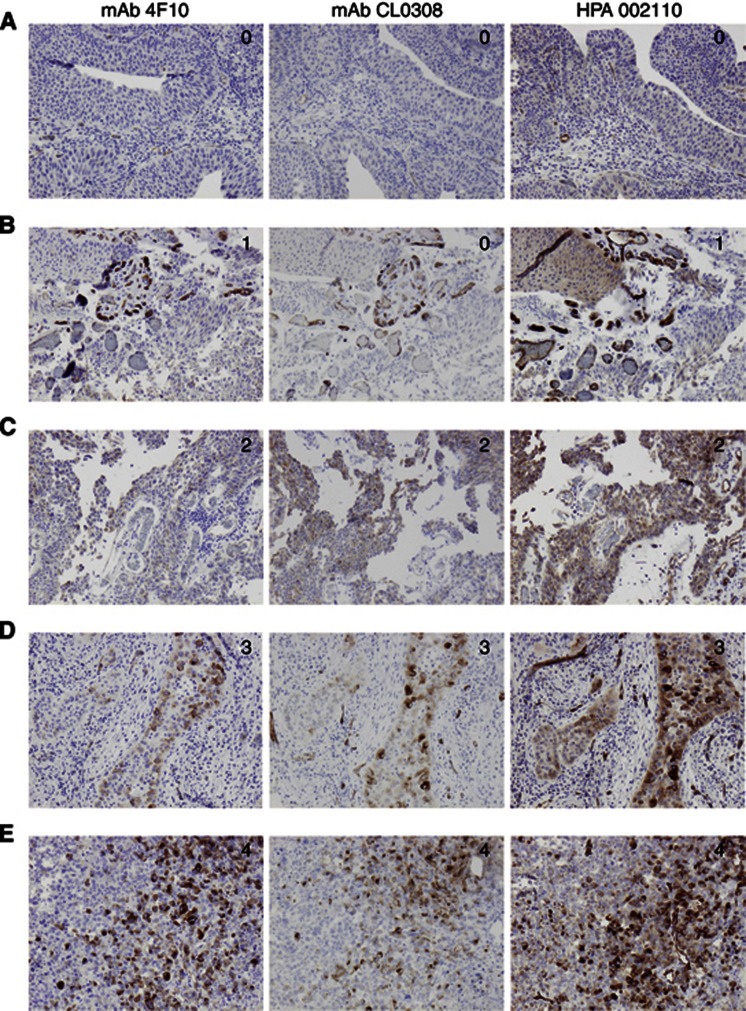

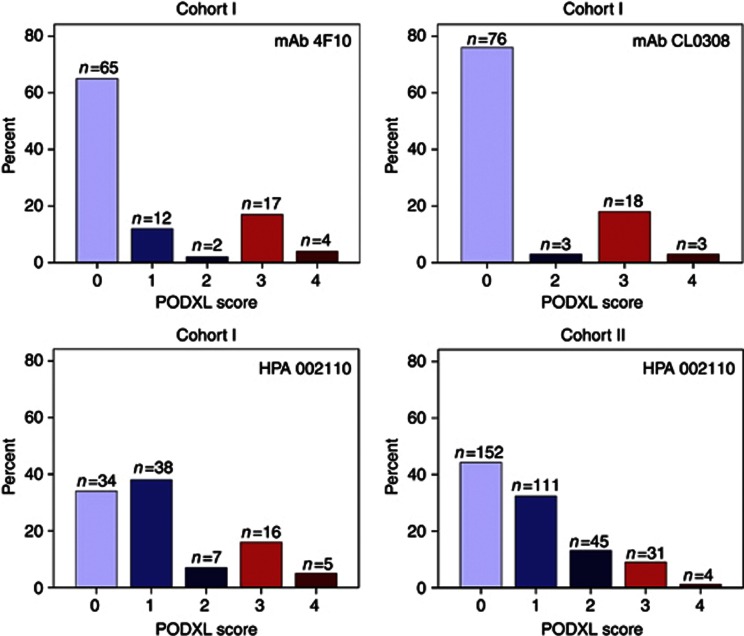

Following antibody optimisation and staining, PODXL expression could be evaluated with all three antibodies in tumours from 100 out of 110 (90.9%) cases in Cohort I and in 343 out of 344 (99.7%) cases in Cohort II. Sample IHC images comparing PODXL expression as assessed by the three different antibodies in Cohort I are shown in Figure 1. The proportion of tumours displaying cytoplasmic staining was lower for both monoclonal antibodies compared with the polyclonal antibody, but there was a 100% correlation regarding the presence and absence of membranous PODXL staining with all three antibodies tested in Cohort I. Notably, the fraction of membranous positivity, that is, tumours having ⩽50% or >50% positivity differed in a few cases. The distribution of all staining modalities for the three different antibodies used in Cohort I and the polyclonal antibody in Cohort II is shown in Figure 2. Membranous PODXL expression was denoted in 21 out of 100 (21.0%) of cases in Cohort I and 35 out of 343 (10.2%) in Cohort II. In line with previous studies, membranous PODXL expression was predominantly observed in subsets of tumour cells at the leading invasive front (Larsson et al, 2011; Dallas et al, 2012; Larsson et al, 2012b).

Figure 1.

Sample images of PODXL staining in urothelial bladder cancer—comparison of three different antibodies. Immunohistochemical images ( × 10 magnification) of five cases (A–E) with tumours denoted as having (0) negative, (1) weak, (2) moderate, (3) partly (<50%) membranous and (4) membranous PODXL expression in >50% of tumour cells, using three different antibodies.

Figure 2.

Distribution of PODXL staining in Cohort I and Cohort II with three different antibodies. Distribution of all categories of PODXL staining (0–4) as assessed by three different antibodies in Cohort I, and with the polyclonal, monospecific antibody in Cohort II. Blue bars (score 0–2) correspond to non-membranous staining and red bars (score 3–4) to membranous staining.

Associations of PODXL expression with patient and tumour characteristics

Analyses of the relationship between PODXL staining and established clinicopathological factors revealed strong, significant associations between membranous PODXL staining and more advanced T-stage and high-grade tumours in both cohorts (Table 1).

Table 1. Associations of PODXL expression with patient and tumour characteristics in two independent patient cohorts.

| |

Cohort I |

|

Cohort II |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PODXL expression | Non-membranous | Membranous | P-value | Non-membranous | Membranous | P-value |

|

n (%) |

79 (79.0) |

21 (21.0) |

|

308 (89.5) |

35 (10.2) |

|

|

Age | ||||||

| ⩽Average | 36 (45.6) | 9 (42.9) | 0.825 | 142 (46.1) | 17 (48.6) | 0.782 |

| >Average |

43 (54.4) |

12 (57.1) |

|

166 (53.9) |

18 (51.4) |

|

|

Gender | ||||||

| Female | 15 (19.0) | 11 (52.4) | 0.002 | 72 (23.4) | 11 (31.4) | 0.293 |

| Male |

64 (81.0) |

10 (47.6) |

|

236 (76.6) |

24 (68.6) |

|

|

T-stage | ||||||

| Ta | 39 (49.4) | 1 (4.8) | <0.001 | 114 (37.0) | 1 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| T1 | 16 (20.3) | 7 (33.3) | 108 (35.1) | 7 (20.0) | ||

| T2–4 |

24 (30.4) |

13 (61.9) |

|

86 (27.9) |

27 (77.1) |

|

|

Grade | ||||||

| Low | 39 (49.4) | 4 (19.0) | 0.013 | 81 (26.3) | 1 (2.9) | 0.002 |

| High | 40 (50.6) | 17 (81.0) | 227 (73.7) | 34 (97.1) | ||

Abbreviation: PODXL=podocalyxin-like.

Associations of membranous PODXL expression with DSS and 5-year OS

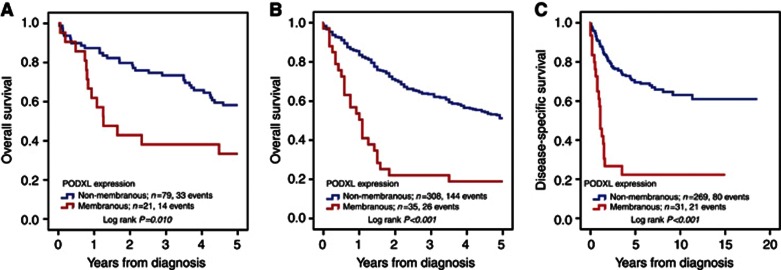

The Kaplan–Meier analysis and the log-rank test demonstrated that membranous PODXL expression (score 3–4) was associated with a significantly reduced 5-year OS compared with non-membranous (score 0–2) expression in both Cohort I and Cohort II (Figure 3A and B). Similar results were seen for DSS in Cohort II (Figure 3C). The associations between membranous PODXL expression and survival were confirmed in Cox univariable analysis (Table 2), and remained significant in multivariable analysis adjusted for age, gender, T-stage and grade (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of 5-year OS and DSS according to PODXL expression. Kaplan–Meier analysis of 5-year OS in (A) Cohort I and (B) Cohort II, and (C) in DSS in Cohort II according to membranous (score 3–4) versus non-membranous (score 0–1) PODXL expression.

Table 2. Relative risks of death from disease and overall death within 5 years according to clinicopathological factors and PODXL expression in Cohort I and Cohort II.

| Cohort I | Cohort II | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Risk of death within 5 years |

Risk of death from disease |

Risk of death within 5 years |

|||||||

|

Univariable |

Multivariable |

Univariable |

Multivariable |

Univariable |

Multivariable |

||||

| n (Events) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | n (Events) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | n (Events) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

|

Age | |||||||||

| Continuous |

100 (47) |

1.05 (1.02–1.08) |

1.05 (1.02–1.09) |

300 (101) |

1.04 (1.02–1.07) |

1.05 (1.03–1.07) |

343 (170) |

1.06 (1.05–1.08) |

1.07 (1.05–1.09) |

|

Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 26 (12) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 72 (28) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 83 (40) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Male |

74 (35) |

0.93 (0.48–1.79) |

1.29 (0.61–2.72) |

228 (73) |

0.80 (0.52–1.24) |

1.00 (0.64–1.56) |

260 (130) |

0.97 (0.68–1.39) |

1.22 (0.85–1.76) |

|

Stage | |||||||||

| Ta | 40 (7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 104 (13) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 115 (35) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| T1 | 23 (16) | 5.08 (2.08–12.40) | 1.86 (0.71–6.00) | 97 (25) | 2.20 (1.13–4.31) | 2.15 (1.10–4.22) | 115 (52) | 1.62 (1.05–2.48) | 1.57 (1.02–2.41) |

| T2–4 |

37 (24) |

6.01 (2.58–14.00) |

2.36 (0.74–7.57) |

99 (63) |

8.93 (4.90–16.27) |

7.56 (4.09–13.97) |

113 (83) |

4.35 (2.92–6.48) |

3.88 (2.57–5.86) |

|

Grade | |||||||||

| Low | 43 (9) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 75 (7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 82 (20) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| High |

57 (38) |

4.64 (2.24–9.64) |

3.61 (1.73–7.56) |

225 (94) |

5.79 (2.68–12.49) |

1.53 (0.59–3.94) |

261 (150) |

3.10 (1.94–4.95) |

1.20 (0.68–2.12) |

|

PODXL expression | |||||||||

| Negative | 79 (33) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 269 (80) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 308 (144) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Positive | 21 (14) | 2.25 (1.20–4.22) | 2.05 (1.06–3.94) | 31 (21) | 4.36 (2.67–7.10) | 2.70 (1.60–4.55) | 35 (26) | 3.10 (2.03–4.72) | 2.18 (1.39–3.41) |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; HR=hazards ratio; PODXL=podocalyxin-like.

Cytoplasmic PODXL expression (score 0–2) was not prognostic in either of the cohorts (Supplementary Figure 2).

Association between PODXL expression, disease progression and survival in patients with Ta and T1 tumours in Cohort II

Next we examined the association between PODXL expression, disease progression within 24 months and 5-year OS in patients with Ta and T1 tumours in Cohort II (Table 3). This revealed that despite the low number of cases with membranous PODXL expression in this patient category, membranous PODXL expression was an independent predictor of an increased risk of disease progression (univariable HR=6.19, 95% CI=1.42–26.98, and multivariable HR=4.60, 95% CI=1.04–20.39). Moreover, membranous PODXL expression was an independent predictor of an increased risk of death from disease (univariable HR=8.34, 95% CI=3.21–21.65, and multivariable HR=7.16, 95% CI=2.72–18.81).

Table 3. Relative risks of disease progression within 24 months and DSS according to clinicopathological factors and PODXL expression in patients with Ta–T1 tumours.

|

Risk of disease progression within 24 months |

Risk of death from disease |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Univariable |

Multivariable |

Univariable |

Multivariable |

|||

| n (Events) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | n (Events) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

|

Age | ||||||

| Continuous |

133 (19) |

1.02 (0.98–1.07) |

1.01 (0.97–1.06) |

201 (38) |

1.03 (1.00–1.06) |

1.03 (1.00–1.06) |

|

Gender | ||||||

| Female | 29 (2) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 38 (5) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Male |

104 (17) |

2.51 (0.58–10.85) |

2.00 (0.46–8.81) |

163 (33) |

1.81 (0.70–4.65) |

1.38 (0.53–3.63) |

|

Stage | ||||||

| Ta | 68 (7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 104 (13) | 1,00 | 1.00 |

| T1 |

65 (12) |

1.93 (0.76–4.91) |

1.31 (0.48–3.62) |

97 (25) |

2.33 (1.19–4.56) |

2.29 (1.16–4.51) |

|

Grade | ||||||

| Low | 48 (3) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 74 (7) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| High |

85 (16) |

3.28 (0.96–11.26) |

2.96 (0.85–10.31) |

127 (31) |

3.04 (1.33–6.92) |

1.59 (0.59–4.31) |

|

PODXL expression | ||||||

| Non-membranous | 130 (17) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 194 (33) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Membranous | 3 (2) | 6.19 (1.42–26.98) | 4.60 (1.04–20.39) | 7 (5) | 8.34 (3.21–21.65) | 7.16 (2.72–18.81) |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; DSS=disease-specific survival; HR=hazards ratio; PODXL=podocalyxin-like.

Discussion

The results from this study demonstrate, for the first time, that membranous expression of PODXL in urothelial bladder cancer strongly correlates with unfavourable tumour characteristics and is an independent factor of DSS and OS. These findings were observed in two independent patient cohorts, including a total number of 446 cases. In one of the cohorts (n=100), three different antibodies were applied for the assessment of PODXL expression, with 100% concordance regarding detection of the presence of membranous staining.

Moreover, and importantly, PODXL was also an independent predictor of tumour progression within 24 months in patients with stage Ta and T1 tumours in Cohort II. These findings indicate that in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, assessment of PODXL could be of potential clinical value for monitoring of tumours with high risk of progression and, hence, patients in need of more aggressive first-line therapy or primary cystectomy. Further studies are warranted to confirm these associations. In more advanced tumours, assessment of PODXL expression may be of value for selection of patients who would benefit from adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy. In colorectal cancer, it has been demonstrated that curatively treated patients with stage III disease, with tumours displaying membranous PODXL expression, had a significant benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy (Larsson et al, 2011).

In the majority of bladder cancer cases, membranous expression of PODXL was primarily observed at the invasive tumour front, findings well in line with previous studies on pancreatic and colorectal cancer (Larsson et al, 2011; Cipollone et al, 2012; Larsson et al, 2012a). Given the comparatively low proportion of tumour cells with membranous PODXL expression within individual tumours, the use of the TMA technique may lead to an underestimation of the proportion of positive cases, and could also, at least in part, explain the differing proportion of tumours with membranous PODXL expression in the two cohorts investigated here. Therefore, although the TMA technique is indispensable in retrospective studies, analysis of PODXL expression on full-face sections should be performed in prospective studies.

In general, the results from the present study demonstrate a higher proportion of tumour cells with membranous PODXL expression in urothelial bladder cancer compared with, for example, colorectal cancer (Larsson et al, 2011; Larsson et al, 2012a) and breast cancer (Somasiri et al, 2004), and a lower proportion than in pancreatic (Ney et al, 2007; Dallas et al, 2012) and high-grade serous ovarian cancer (Cipollone et al, 2012). The high proportion of tumours with membranous PODXL expression within the latter two cancer forms are, however, well in line with their aggressive tumour phenotype.

The observation that it is the membranous, rather than cytoplasmic, subcellular localisation of PODXL that confers poor prognosis in urothelial bladder cancer is well in line with studies on several other cancer forms, for example, colorectal, pancreatic and ovarian malignancies (Larsson et al, 2011; Cipollone et al, 2012; Dallas et al, 2012; Larsson et al, 2012a). The mechanistic basis for these findings may, however, differ according to tumour type. Cipollone et al (2012) demonstrated that in high-grade serous epithelial ovarian cancer, localisation of podocalyxin to the cell surface, but not cytoplasm, was associated with a significantly decreased survival. In vitro data further demonstrated how forced overexpression of PODXL in ovarian cancer cells led to a decreased cell adhesion to mesothelial monolayers and fibronectin, and to reduced β-1 integrin levels on the cell surface, altogether proposing that PODXL may contribute to the formation of free-floating high-grade serous tumour nodules during the initial steps of transperitoneal metastasis, the most important route to disease progression in EOC (Cipollone et al, 2012). In pancreatic cancer, PODXL has been demonstrated to be a functional ligand of E- and L-selectins, suggesting that its expression may promote haematogenic metastatic spread by facilitating binding of circulating tumour cells to selectin-expressing host cells (Dallas et al, 2012). PODXL is also a key orchestrator of apical morphology and microvillus formation in epithelial cells, whereby the full-length protein acts to recruit NHERF-1 to the apical domain, but its extracellular domain and transmembrane region are sufficient for direct recruitment of filamentous actin and ezrin to the plasma membrane, independent of NHERF binding (Nielsen et al, 2007). Podocalyxin-like has also been demonstrated to form a complex with ezrin in breast and prostate cancer cells, leading to increased in vitro migration and invasion (Sizemore et al, 2007).

Although ezrin expression has been demonstrated to correlate with poor prognosis in several cancer forms, for example, colorectal (Elzagheid et al, 2008), breast (Bruce et al, 2007) and pancreatic cancer (Cui et al, 2010), the only, to our knowledge, hitherto published report on the prognostic significance of ezrin expression in urothelial bladder cancer demonstrated low membranous ezrin expression to be an independent marker of progression and DSS in 92 patients with T1G3 bladder cancer undergoing non-maintenance BCG treatment (Palou et al, 2009). If these associations can be confirmed in larger patient cohorts, it would also be of interest to examine whether PODXL and ezrin may have opposing functional roles in the progression of urothelial bladder cancer.

As the assessment of PODXL in urine has proven useful for diagnosing various conditions related to glomerular damage (Sato et al, 2009; Zheng et al, 2011), it would also be of potential interest to investigate whether PODXL levels in urine correlate to its tumour-specific expression, and to clinical outcome, in patients with urothelial bladder cancer. Potentially, this could prove to be a non-invasive method for better monitoring of patients with non-muscle tumours at risk of progressive disease.

In summary, results from immunohistochemical analyses of tumours from two independent patient cohorts demonstrate that membranous PODXL expression is an independent marker for progressive disease and death in patients with urothelial bladder cancer. These findings add another piece of evidence to the growing body of data, from bench as well as bedside, supporting the role of PODXL as a driver of a more malignant tumour phenotype in several major cancer forms. The functional mechanisms relevant to bladder cancer and the potential clinical utility of PODXL as a biomarker for improved treatment stratification of patients with urothelial bladder cancer warrant further study.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Swedish Cancer Society, the Gunnar Nilsson Cancer Foundation, Region Skåne and the Research Funds of Skåne University Hospital.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bruce B, Khanna G, Ren L, Landberg G, Jirstrom K, Powell C, Borczuk A, Keller ET, Wojno KJ, Meltzer P, Baird K, McClatchey A, Bretscher A, Hewitt SM, Khanna C. Expression of the cytoskeleton linker protein ezrin in human cancers. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2007;24 (2:69–78. doi: 10.1007/s10585-006-9050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey G, Neville PJ, Liu X, Plummer SJ, Cicek MS, Krumroy LM, Curran AP, McGreevy MR, Catalona WJ, Klein EA, Witte JS. Podocalyxin variants and risk of prostate cancer and tumor aggressiveness. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15 (5:735–741. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung HH, Davis AJ, Lee TL, Pang AL, Nagrani S, Rennert OM, Chan WY. Methylation of an intronic region regulates miR-199a in testicular tumor malignancy. Oncogene. 2011;30 (31:3404–3415. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipollone JA, Graves ML, Kobel M, Kalloger SE, Poon T, Gilks CB, McNagny KM, Roskelley CD. The anti-adhesive mucin podocalyxin may help initiate the transperitoneal metastasis of high grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2012;29 (3:239–252. doi: 10.1007/s10585-011-9446-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Li T, Zhang D, Han J. Expression of Ezrin and phosphorylated Ezrin (pEzrin) in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Invest. 2010;28 (3:242–247. doi: 10.3109/07357900903124498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallas MR, Chen SH, Streppel MM, Sharma S, Maitra A, Konstantopoulos K. Sialofucosylated podocalyxin is a functional E- and L-selectin ligand expressed by metastatic pancreatic cancer cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303 (6:C616–C624. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00149.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elzagheid A, Korkeila E, Bendardaf R, Buhmeida A, Heikkila S, Vaheri A, Syrjanen K, Pyrhonen S, Carpen O. Intense cytoplasmic ezrin immunoreactivity predicts poor survival in colorectal cancer. Hum Pathol. 2008;39 (12:1737–1743. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heukamp LC, Fischer HP, Schirmacher P, Chen X, Breuhahn K, Nicolay C, Buttner R, Gutgemann I. Podocalyxin-like protein 1 expression in primary hepatic tumours and tumour-like lesions. Histopathology. 2006;49 (3:242–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjelm B, Brennan DJ, Zendehrokh N, Eberhard J, Nodin B, Gaber A, Ponten F, Johannesson H, Smaragdi K, Frantz C, Hober S, Johnson LB, Pahlman S, Jirstrom K, Uhlen M. High nuclear RBM3 expression is associated with an improved prognosis in colorectal cancer. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2011;5 (11–12:624–635. doi: 10.1002/prca.201100020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerjaschki D, Sharkey DJ, Farquhar MG. Identification and characterization of podocalyxin--the major sialoprotein of the renal glomerular epithelial cell. J Cell Biol. 1984;98 (4:1591–1596. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.4.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson A, Fridberg M, Gaber A, Nodin B, Leveen P, Jonsson G, Uhlen M, Birgisson H, Jirstrom K. Validation of podocalyxin-like protein as a biomarker of poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012a;12:282. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson AH, Fridberg M, Gaber A, Nodin B, Leveen P, Jonsson GB, Uhlen M, Birgisson H, Jirstrom K. Validation of podocalyxin-like protein as a biomarker of poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012b;12 (1:282. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson A, Johansson ME, Wangefjord S, Gaber A, Nodin B, Kucharzewska P, Welinder C, Belting M, Eberhard J, Johnsson A, Uhlen M, Jirstrom K. Overexpression of podocalyxin-like protein is an independent factor of poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011;105 (5:666–672. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masood S, Sriprasad S, Palmer JH, Mufti GR. T1G3 bladder cancer--indications for early cystectomy. Int Urol Nephrol. 2004;36 (1:41–44. doi: 10.1023/b:urol.0000032688.37789.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNagny KM, Pettersson I, Rossi F, Flamme I, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Graf T. Thrombomucin, a novel cell surface protein that defines thrombocytes and multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. J Cell Biol. 1997;138 (6:1395–1407. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.6.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ney JT, Zhou H, Sipos B, Buttner R, Chen X, Kloppel G, Gutgemann I. Podocalyxin-like protein 1 expression is useful to differentiate pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas from adenocarcinomas of the biliary and gastrointestinal tracts. Hum Pathol. 2007;38 (2:359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen JS, Graves ML, Chelliah S, Vogl AW, Roskelley CD, McNagny KM. The CD34-related molecule podocalyxin is a potent inducer of microvillus formation. PLoS ONE. 2007;2 (2:e237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palou J, Algaba F, Vera I, Rodriguez O, Villavicencio H, Sanchez-Carbayo M. Protein expression patterns of ezrin are predictors of progression in T1G3 bladder tumours treated with nonmaintenance bacillus Calmette-Guerin. Eur Urol. 2009;56 (5:829–836. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan D, Shipley WU, Garnick MB, Russell PJ, Richie JP. Biology and management of bladder cancer. N Engl J Med. 1990;322 (16:1129–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199004193221607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Wharram BL, Lee SK, Wickman L, Goyal M, Venkatareddy M, Chang JW, Wiggins JE, Lienczewski C, Kretzler M, Wiggins RC. Urine podocyte mRNAs mark progression of renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20 (5:1041–1052. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007121328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopperle WM, Kershaw DB, DeWolf WC. Human embryonal carcinoma tumor antigen, Gp200/GCTM-2, is podocalyxin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300 (2:285–290. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02844-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sizemore S, Cicek M, Sizemore N, Ng KP, Casey G. Podocalyxin increases the aggressive phenotype of breast and prostate cancer cells in vitro through its interaction with ezrin. Cancer Res. 2007;67 (13:6183–6191. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloway MS, Lopez AE, Patel J, Lu Y. Results of radical cystectomy for transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder and the effect of chemotherapy. Cancer. 1994;73 (7:1926–1931. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940401)73:7<1926::aid-cncr2820730725>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somasiri A, Nielsen JS, Makretsov N, McCoy ML, Prentice L, Gilks CB, Chia SK, Gelmon KA, Kershaw DB, Huntsman DG, McNagny KM, Roskelley CD. Overexpression of the anti-adhesin podocalyxin is an independent predictor of breast cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2004;64 (15:5068–5073. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg CN. The treatment of advanced bladder cancer. Ann Oncol. 1995;6 (2:113–126. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a059105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M, Lv LL, Ni J, Ni HF, Li Q, Ma KL, Liu BC. Urinary podocyte-associated mRNA profile in various stages of diabetic nephropathy. PloS ONE. 2011;6 (5:e20431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.