Abstract

Background:

Keratosis pilaris (KP) is characterized by keratinous plugs in the follicular orifices and varying degrees of perifollicular erythema. The most accepted theory of its pathogenesis proposes defective keratinization of the follicular epithelium resulting in a keratotic infundibular plug. We decided to test this hypothesis by doing dermoscopy of patients diagnosed clinically as keratosis pilaris.

Materials and Methods:

Patients with a clinical diagnosis of KP seen between September 2011 and December 2011 were included in the study. A clinical history was obtained and examination and dermoscopic evaluation were performed on the lesions of KP.

Results:

The age of the patients ranged from 6-38 years. Sixteen patients had history of atopy. Nine had concomitant ichthyosis vulgaris. All the 25 patients were found to have coiled hair shafts within the affected follicular infundibula. The hair shafts were extracted with the help of a sterile needle and were found to retain their coiled nature. Perifollicular erythema was seen in 11 patients; perifollicular scaling in 9.

Conclusion:

Based on our observations and previously documented histological data of KP, we infer that KP may not be a disorder of keratinization, but caused by the circular hair shaft which ruptures the follicular epithelium leading to inflammation and abnormal follicular keratinization.

Keywords: Atopy, coiled hair, Keratosis Pilaris

INTRODUCTION

Keratosis pilaris (KP) is an autosomal dominant disorder that is classically characterized by keratinous plugs in the follicular orifices and varying degrees of perifollicular erythema [Figure 1]. It affects nearly 50-80% of all adolescents and approximately 40% of adults.[1] Most people with KP are otherwise asymptomatic and are frequently unaware of the condition. In general, KP is frequently cosmetically displeasing but medically harmless. The sites of predilection are the extensor surfaces of the upper arms (92%), thighs (59%) and buttocks (30%).[2] The classically described histopathology is distention of the follicular orifice by a keratinous plug that may contain one or more twisted hairs.[3]

Figure 1.

Keratosis pilaris: Keratotic follicular papules present on the extensor aspect of both forearms

Known associations of KP include atopy (55%),[4] ichthyosis vulgaris,[5] scarring alopecia,[6] cardio–fascio–cutaneous syndrome,[7] ectodermal dysplasia[8], KID syndrome,[9] obesity,[10] prolidase deficiency[11] and Down's syndrome.[12] Conditions presenting as keratotic follicular papules may be considered in the differential diagnosis of KP. These include phrynoderma, follicular eczema, follicular lichen planus, juvenile pityriasis rubra pilaris, acne vulgaris, acneiform drug eruption, trichostasis spinulosa, ichthyosis follicularis, scurvy, eruptive vellus hair cysts and perforating folliculitis.

The pathogenesis of KP is still not well understood. The most accepted theory proposes defective keratinization of the follicular epithelium resulting in a keratotic infundibular plug.[5] We decided to test this hypothesis by doing dermoscopy of patients diagnosed clinically as keratosis pilaris. We correlated the findings with the clinical features in these cases to further our understanding of the disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional, observational study was conducted on 25 patients who presented to our outpatient department between September 2011 and December 2011 and were clinically diagnosed with KP. A clinical history was obtained; examination and dermoscopic evaluation were performed on the lesions of KP. The dermoscope used was a triple light source, non-contact, videodermoscope (Ultrascan©, Dermaindia) and patients were evaluated using both the white light and polarizing light. Still images of the lesions were shot and later analyzed and correlated with clinical features.

RESULTS

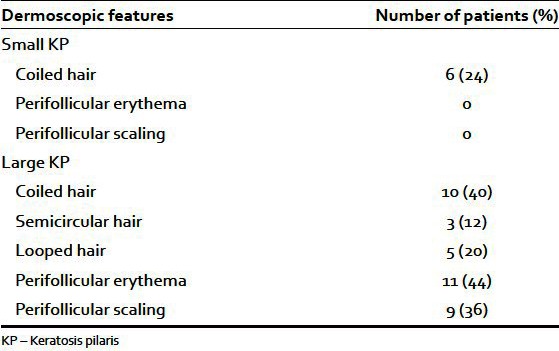

The age of the patients who underwent dermoscopic examination ranged from 6-38 years with average age of 18 years. The male:female ratio was 1:2. Of the 25 patients included in the study, 16 patients had history suggestive of atopy. Nine patients had concomitant ichthyosis vulgaris. One other patient had concomitant follicular eczema. All the 25 patients were found to have circular, twisted or coiled hair shafts within the affected follicular infundibula which could be extracted using a 26G needle. Six patients were found to have small papules of keratosis pilaris; 19 had larger lesions.

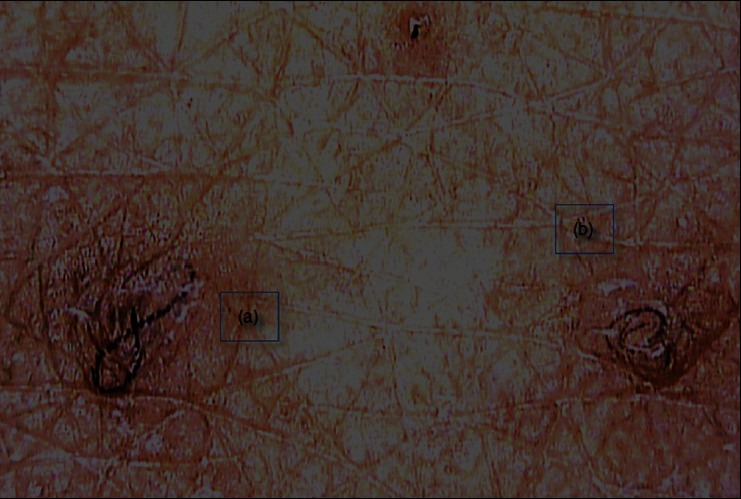

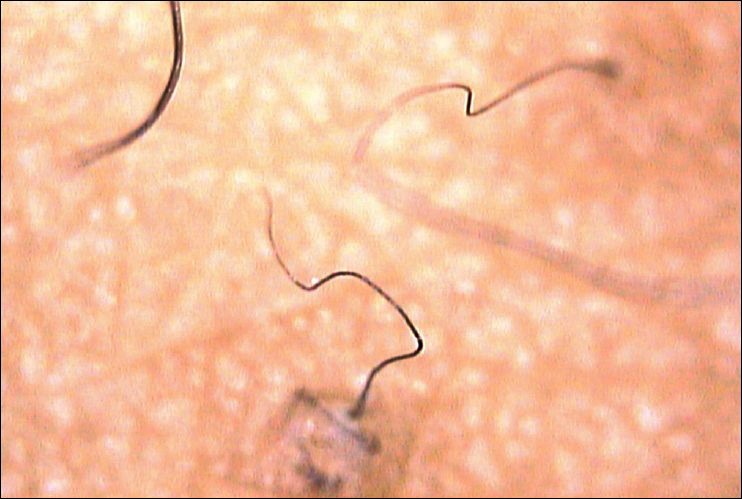

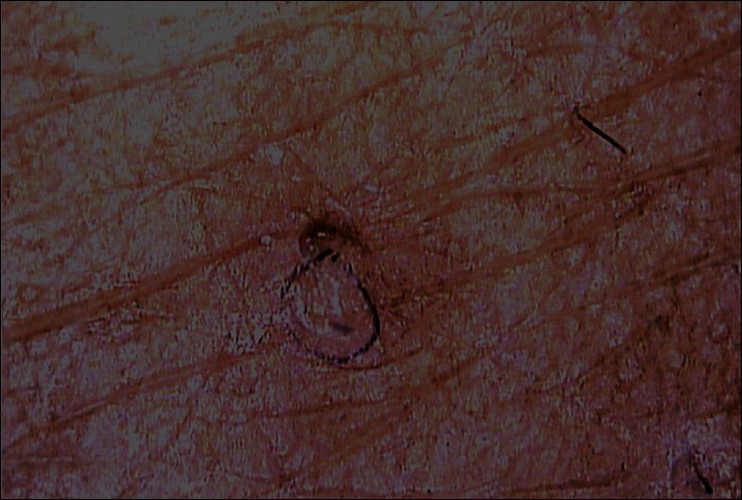

Dermoscopic examination with white light revealed that all the small papules of KP had a coiled or semicircular intermediate hair embedded superficially in the epidermis. None of the small lesions had perifollicular erythema or perifollicular scaling [Figure 2]. In larger lesions, a coiled hair shaft was visualized emerging from the infundibulum. The hair shaft formed a semicircle in 3 patients and a loop in 5 patients [Figure 3]. Even after the coiled hair shaft, embedded in the uppermost epidermis was dislodged from it with the help of a needle, it continued to maintain its coiled nature [Figure 4]. Perifollicular erythema was seen in 11 patients. Perifollicular scaling was seen in 9 patients [Figure 5, Table 1]. Three of the female patients had undergone waxing for hair removal prior to the dermoscopic evaluation but coiled hair could be visualized embedded in the superficial epidermis even in these cases. It was noted that perifollicular erythema was more prominent in these cases.

Figure 2.

Early KP lesion with a circular hair shaft emerging from a normal-appearing follicular opening

Figure 3.

A looped hair shaft (a) and a coiled hair shaft (b) associated erythema and pigmentation. Note lack of keratin plug in (a)

Figure 4.

The hair shaft retains its coiled nature even after being extracted from the superficial epidermis with a sterile needle

Figure 5.

Perifollicular erythema and scaling surrounding a larger KP lesion

Table 1.

Dermoscopic features in keratosis pilaris

DISCUSSION

Keratosis pilaris is believed to be a disorder of keratinization[13] and there is very limited literature describing its etiopathogenesis. There are no previous studies evaluating the dermoscopic features of KP. The recent identification of ‘loss-of-function’ mutations in the structural protein filaggrin as a widely replicated major risk factor for atopic eczema and associated conditions e.g., ichthyosis vulgaris and keratosis pilaris, suggests that the primary pathogenetic mechanism in KP is an epithelial barrier abnormality.[14] Yet, much is still unknown about the sequence of biologic, physicochemical, and aberrant regulatory events leading to the clinical manifestations of KP. It is proposed to be a disorder of the keratinocytes caused by a mutation in the FLG gene which codes for fillagrin that is responsible for inducing both hyperkeratosis and inflammatory changes. More than 22 mutations have been described till date.[15] Hyperandrogenism has been known to cause hyperkeratinization of the pilosebaceous unit of terminal hairs in response to circulating androgens probably leading to increased incidence of KP in the pubertal age group. It has also been suggested that insulin resistance may play a role in the development of keratosis pilaris.[10] In a previous study it was found that young patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus had a higher prevalence of KP than healthy controls, with a high correlation with body mass index (BMI) and ichthyosiform skin changes of the legs.[16,17]

Currently available treatment modalities for KP include various keratolytics, vitamin D3 analogs, topical systemic retinoids and various laser therapies.[18] In spite of the availability of such a multitude of treatments, satisfactory clinical outcomes are rare. This prompted us to evaluate the clinical and dermoscopic features of KP and review the etiological hypotheses.

Upon dermoscopy, we consistently found circular hair shafts mostly within normal-appearing follicular openings. White light examination revealed the clinically visible follicular papules harboring a circular hair shaft embedded in their sides, but sans follicular plugs. At times, these papules showed the hair to be thicker and forming larger coils embedded in the superficial epidermis. These hair shafts were found to retain their coiled nature even after they were extracted from the follicular plugs, indicating that the defect in KP may not be of keratinization, but of the circular hair shaft which ruptures the follicular epithelium, leading to inflammation and abnormal follicular keratinization. Waxing exacerbated the lesions probably secondary to an increased perifollicular inflammation secondary to trauma.

CONCLUSION

Even though keratosis pilaris is a common clinical diagnosis, little is known about its etiology. It was considered to be a defect in the follicular keratinization, though dermoscopic examination did not support this theory. We propose that KP is primarily caused by a hair shaft defect. Further studies are required to evaluate the role of laser hair removal in the treatment of KP to reinforce this hypothesis.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alai NN. Keratosis pilaris. Emedicine. [Last updated on 2012 Mar 23 2012, Last accessed on 2012 Mar 03]. Available from http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1070651-overview .

- 2.Judge MR, McLean WH, Munro CS. Disorders of keratinization. In: Burns DA, Breathnach SM, Cox NH, Griffiths CE, editors. Rook's textbook of dermatology. 7th ed. Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishing; 2004. p. 34. (60-34). 62. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers M. Keratosis pilaris and other inflammatory follicular keratotic syndromes. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, editors. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. 7th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008. pp. 749–53. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebling FJ, Marks R, Rook A. Disorders of keratinization. In: Rook A, Wilkinson DS, Ebling FJ, Champion RH, Burton JL, editors. Textbook of dermatology. 4th ed. Oxford Blackwell Scientific Publication; 1986. pp. 1435–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mevorah B, Marazzi A, Frenk E. The prevalence of accentuated palmoplantar markings and keratosis pilaris in atopic dermatitis, autosomal dominant ichthyosis and control dermatological patients. Br J Dermatol. 1985;112:679–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1985.tb02336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romine KA, Rothschild JG, Hansen RC. Cicatricial Alopecia and Keratosis Pilaris. Keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:381–2. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1997.03890390121018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pierard GE, Soyeur-Broux M, Estrada JA, Pierard-Franchimont C, Soyeur D, Verloes A. Cutaneous presentation of the cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:920–2. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chitty LS, Dennis N, Baraitser M. Hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia of hair, teeth, and nails: Case reports and review. J Med Genet. 1996;33:707–10. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.8.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McHenry PM, Nevin NC, Bingham EA. The association of keratosis pilaris atrophicans with hereditary woolly hair. Pediatr dermatol. 1990;7:202–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1990.tb00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barth J, Wojnarowska F, Dawber R. Acanthosis nigricans, insulin resistance and cutaneous virilism. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:613–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb02561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kokturk A, Kaya TI, Ikizoglu G, Koca A. Prolidase deficiency. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:45–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.1353_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daneshpazhooh M, Mohammad-Javad NT, Bigdeloo L, Yoosefi M. Mucocutaneous findings in 100 children with down syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:317–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang S, Schwartz RA. Keratosis pilaris: A common follicular hyperkeratosis. Cutis. 2008;82:177–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Regan GM, Sandilands A, McLean WH, Irvine AD. Filaggrin in atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:R2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown SJ, Relton CL, Liao H, Zhao Y, Sandilands A, Wilson IJ, et al. Filaggrin null mutations and childhood atopic eczema: A population-based case-control study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:940–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barth JH, Wojnarowska F, Dawber RP. Is keratosis pilaris another androgen-dependent dermatosis? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1988;13:240–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1988.tb00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yosipovitch G, Mevorah B, Mashiach J, Chan YH, David M. High body mass index, dry scaly leg skin and atopic conditions are highly associated with keratosis pilaris. Dermatology. 2000;201:34–6. doi: 10.1159/000018425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerbig AW. Treating keratosis pilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:457. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.122733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]