Abstract

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women, accounting for about 30% of all cancers. In contrast, breast cancer is a rare disease in men, accounting for less than 1% of all cancers. Up to 10% of all breast cancers are hereditary forms, caused by inherited germ-line mutations in “high-penetrance,” “moderate-penetrance,” and “low-penetrance” breast cancer susceptibility genes. The remaining 90% of breast cancers are due to acquired somatic genetic and epigenetic alterations. A heterogeneous set of somatic alterations, including mutations and gene amplification, are reported to be involved in the etiology of breast cancer. Promoter hypermethylation of genes involved in DNA repair and hormone-mediated cell signaling, as well as altered expression of micro RNAs predicted to regulate key breast cancer genes, play an equally important role as genetic factors in development of breast cancer. Elucidation of the inherited and acquired genetic and epigenetic alterations involved in breast cancer may not only clarify molecular pathways involved in the development and progression of breast cancer itself, but may also have an important clinical and therapeutic impact on improving the management of patients with the disease.

Keywords: breast cancer, inherited susceptibility, acquired alterations, epigenetics

Introduction

Breast cancer is currently the most common cancer among women, accounting for about 30% of all cancers.1 In contrast, breast cancer is a rare disease in men, accounting for less than 1% of all cancers.2 The age-specific incidence rates for breast cancer in women increase rapidly until the age of 50 years, and then increase at a slower rate for older women, while incidence rates for breast cancer in men increase linearly and steadily with age. Overall, current epidemiologic and pathologic data, such as age-frequency distribution, age-specific incidence rate patterns, and prognostic factor profiles, suggest that male breast cancer is similar to postmenopausal female breast cancer.2 It is generally accepted that breast cancer may represent the same disease entity in both genders, and common hormonal, genetic, and environmental risk factors are involved in the pathogenesis of breast cancer in women and men. Hormonal changes, such as increased estrogen exposure due to diabetes, obesity or liver disease, and environmental and lifestyle factors, such as carcinogen exposure or alcohol intake, are associated with risk of developing breast cancer.3 However, the major predisposition factor for breast cancer is a positive family history of the disease. Patients of both genders with a positive first-degree family history have a twofold increased risk, which increases to more than fivefold with the number of affected relatives and early onset relatives, thus suggesting a relevant genetic component in breast cancer risk.4 It is estimated that up to 10% of all breast cancers are hereditary forms, caused by inherited germ-line mutations in breast cancer susceptibility genes. Commonly, inherited mutations are loss-of-function mutations that occur in tumor suppressor genes involved in DNA repair and cell cycle checkpoint activation.1 The remaining 90% of breast cancers are due to acquired somatic, genetic, and epigenetic alterations.5 Genetic alterations include gain-of-function mutations, amplification, deletions, and rearrangements occurring in genes which stimulate cell growth, division, and survival.6 Epigenetic deregulation, mainly due to promoter methylation, may also contribute to the abnormal expression of these genes.7 In addition, the involvement of micro RNAs (miRNAs) in modulating gene expression in the development of breast cancer has been recently reported.8 The focus of this review will be on the most relevant inherited and acquired alterations in the development of breast cancer in both genders. We did a systematic literature search using PubMed to provide a synopsis of the current understanding and future directions of research in this field. We selected original articles and reviews published up to April 2011. The following search key terms were used to query the PubMed website: “inherited breast cancer,” “breast cancer AND susceptibility,” “breast cancer AND somatic alterations,” “breast cancer AND epigenetic,” “breast cancer AND miRNA.” The abstracts resulting from these queries were individually analyzed for relevance.

Inherited susceptibility to breast cancer

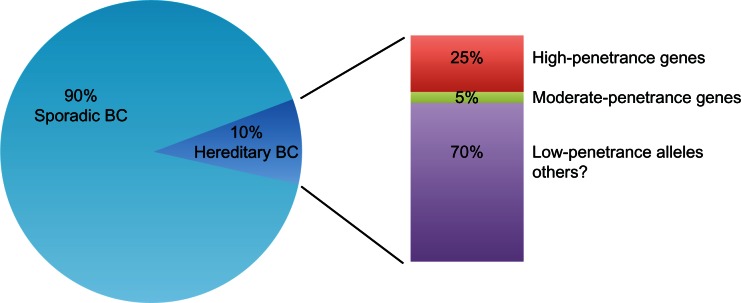

To date, 5%–10% of all breast cancers are caused by inherited germ-line mutations in well identified breast cancer susceptibility genes.1 According to their mutation frequency and the magnitude of their impact in breast cancer susceptibility, these genes can be divided into “high-penetrance,” “moderate-penetrance,” and “low-penetrance” genes (Figure 1).9 Variants in the two major high-risk breast cancer genes, ie, BRCA1 and BRCA2, occur rarely in the population, but confer a high risk of breast cancer to the individual.1P53 and PTEN, two genes involved in rare syndromes (Li-Fraumeni and Cowden syndromes, respectively), also confer a high risk of breast cancer.1 However, P53 and PTEN germ-line mutations are very rare, and it is unlikely that these mutations would account for a proportion of breast cancers in the absence of their respective syndromes.10,11

Figure 1.

Genetic susceptibility in hereditary breast cancer. Up to 10% of all breast cancers are caused by inherited germ-line mutations in breast cancer susceptibility genes. High-penetrance genes (BRCA1 and BRCA2) contribute to 25% of hereditary breast cancer, moderate-penetrance genes (CHEK2, ATM, PALB2, BRIP1, RAD51C) contribute less than 5% to the risk of breast cancer. The great majority of hereditary breast cancer may be due to common low-penetrance alleles or other still unknown genetic factors.

Abbreviation: BC, breast cancer.

Overall, high-risk genes account for about 25% of inherited breast cancers (Figure 1).12 Variants in genes functionally related to BRCA1/2 in DNA repair pathways confer an intermediate risk of breast cancer. These variants are rare, occurring in less than 1% of the population, and their contribution to the risk of breast cancer is less than 5% (Figure 1).13 Recently, a third class of low-penetrance susceptibility alleles has been identified. These alleles, which may occur in genic or nongenic regions, confer a lower risk but are very common in the population.13 Due to their low penetrance, the real contribution of these common variants to breast cancer risk is not entirely clear (Figure 1). Overall, this scenario suggests that the majority of genetic factors involved in breast cancer susceptibility are still unknown.

High-penetrance breast cancer genes

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are the most important breast cancer susceptibility genes in high-risk families (Table 1). BRCA1/2 mutations are considered to be responsible for approximately 30% of breast cancer cases with a family history of breast/ovarian cancer, and it has been estimated that inherited BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations account for 5%–10% of the total percentage of breast cancer.14–16

Table 1.

Classes of genetic susceptibility and comparison of their different features

| High-penetrance | Moderate-penetrance | Low-penetrance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genes | BRCA1, BRCA2 | CHEK2, ATM, PALB2, BRIP1, RAD51C | 10q26.13 (FGFR2), 2q33 (CASP8), 5q11.2 (MAP3K1), 11p15.5 (LSP1), 16q12.1 (TNRC9), 6q25 (eSR1), 14q24 (RAD51L1), 2q35, 8q24, 5p12, 1p11 |

| Population frequency | <0.1% | MAF < 2% | MAF > 10% |

| Cancer risk (odds ratio) | >10.0 | >2.0 | 1.1–1.6 |

| Population attributable risk | Small | Individually small | High |

| Functional effect | Direct effect of mutation | Direct effect of variant | Linkage disequilibrium with causal variants |

| Strategy for identification | Linkage and positional cloning; resequencing of candidate genes | Resequencing of candidate genes | Case-control studies; genome-wide association study |

In women, germ-line BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations confer a high risk for developing breast cancer by age 70 years. Initial studies based on multiple-case families, reported a female breast cancer risk at age 70 years in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers of 85% and 84%, respectively.17 Later meta-analyses showed that the average cumulative female breast cancer risk in BRCA1 mutation carriers by 70 years of age, unselected for family history, was 46%–65% and the corresponding estimates for BRCA2 were 43%–45%.18,19

In male breast cancer cases, BRCA2 mutations are much more common than BRCA1. Mutations in the BRCA2 gene are estimated to be responsible for 60%–76% of male breast cancers occurring in high-risk breast cancer families, whereas the BRCA1 mutation frequency ranges from 10% to 16%.17,20 In a large population-based male breast cancer series, we reported a mutation frequency of about 7% and 2% for BRCA2 and BRCA1, respectively.21 Interestingly, a founder effect was observed in BRCA1-associated male breast cancer cases.22

All known BRCA1/2 mutations are recorded in the Breast Information Core database (http://www.nhgri.nih.gov/Intramural_research/Lab_transfer/Bic/). To date, 1643 distinct germ-line BRCA1 mutations and 2015 BRCA2 mutations have been reported in the database. The great majority of BRCA1/2 mutations in breast cancer are predicted to truncate the protein product. The most common type of mutations are small frameshift insertions or deletions, nonsense mutations, or mutations affecting splice sites resulting in a deletion of complete or partial exons or insertion of intronic sequences. The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium has reported that approximately 70% of BRCA1 mutations and 90% of BRCA2 mutations in linked families are truncating mutations.4 In addition to truncating mutations, an elevated number of missense variants has been identified. The most frequent are the BRCA1 G61C in the RING-finger codon and the BRCA2 I2490T in exon 15.

Some studies also indicate that BRCA1/2 polymorphic variants could be associated with an increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer.23,24 Association between the BRCA2 N372H variant and increased breast cancer risk in particular has been reported from population-based studies.25 Interestingly, we observed an association between the BRCA2 N372H variant and risk of male breast cancer in young patients.26 Breast cancer risk in women is influenced by the position of the mutation within the gene sequence. Women with a mutation in the central region of BRCA1 were shown to have a lower breast cancer risk than women with mutations outside this region. BRCA2 mutations located in the central region, referred to as the ovarian cancer cluster region, also appear to be associated with a lower breast cancer risk and a higher ovarian cancer risk than other BRCA2 mutations.27,28

Specific BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations show a high frequency in specific countries or ethnic groups, particularly in genetically isolated populations. These mutations descend from a single founder. For example, two founder mutations in BRCA1 (185delAG and 5382insC) and one in BRCA2 (6174delT) account for the majority of all BRCA1/2 mutations (>90%) in the Ashkenazi Jewish population.29BRCA1 185delAG is present in about 1% of Ashkenazi Jews and in 20% of Ashkenazi women affected by breast cancer before the age of 50 years.18,30 A single BRCA2 mutation (999del5) has been found in the majority of multiple-case breast cancer families in the Icelandic population.31,32 The BRCA2 999del5 accounts for about 8% of female breast cancer, rising to 24% of female breast cancers before the age of 40 years, and for about 38% of male breast cancers.32,33 In Italy, a historically and genetically heterogeneous country, BRCA1/2 founder mutations are found in small isolated geographic areas. The BRCA1 5083del19 was found in a geographically homogeneous population from Calabria, a region of Southern Italy, where it accounts for 33% of overall gene mutations.34 A high frequency of BRCA1 5083del19 mutation has also been identified in the population of Sicily, a region near to Calabria.35 Other regional founder mutations have been reported in Tuscany (BRCA1 1499insA, BRCA1 3347delAG), a region in Central Italy of ancient settlement.21,22,36

In addition to point mutations, small deletions and insertions, large-scale BRCA1/2 rearrangements, including insertions, deletions, or duplications of more than 500 kb of DNA, have been identified in both male and female breast cancer.37–40 Large genomic rearrangements may account for 3%–15% of all BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations.38 The higher density of Alu repeat sequences in BRCA1 and both Alu and non-Alu repetitive DNA in BRCA2 are thought to contribute to the large number of deletions and duplications observed in these genes.37,40–43 The frequency of large BRCA1 genomic rearrangements in families with a strong family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, varies greatly (0%–36%) in different populations.37–39 The frequency of large BRCA2 genomic rearrangements seems to be lower (1%–2%) in comparison with BRCA1.41,44 Interestingly, large genomic rearrangements in BRCA2 are more frequent in families with male breast cancer.38,43

Moderate-penetrance breast cancer genes

Overall, fewer than 10% of breast cancers are attributable to known mutations in the breast cancer susceptibility genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2.13 Recently, direct interrogation of candidate genes involved in BRCA1/2-associated DNA damage repair pathway has led to the identification of other breast cancer susceptibility genes, classified as moderate-penetrance genes (Table 1). Variants found in this class of genes confer a smaller risk of breast cancer than BRCA1/2 and, because of their rarity, are very difficult to detect in the population. Overall, mutations in moderate-penetrance genes account for less than 3% of the familial risk of breast cancer.13

CHEK2 1100delC was the first moderate breast cancer risk allele identified and was associated with a twofold risk among breast cancer cases unselected for family history and fivefold among familial breast cancer cases.45,46 The CHEK2 1100delC mutation has also been shown to confer approximately a tenfold increase in breast cancer risk in men lacking BRCA1/2 mutations, and was estimated to account for 9% of familial high-risk male breast cancer cases.45 However, this association is not so evident in male breast cancer series unselected for family history, in which it was reported that the CHEK2 1100delC is unlikely to account for a significant proportion of male breast cancer cases.47–50 The contribution of the CHEK2 1100delC mutation to breast cancer predisposition in both genders varies by ethnic group and from country to country. A decreased frequency of the 1100delC allele in North to South orientation has been observed in Europe both for male and female breast cancer.50–53 Identification of the CHEK2 1100delC mutation as a breast cancer-associated allele induced mutational screening of the whole CHEK2 gene sequence. However, at present, only a small number of rare truncating mutations and missense variants have been reported in breast cancer cases.54,55

ATM was first proposed as a breast cancer predisposition gene by epidemiological studies that reported an increased breast cancer risk in relatives of patients with ataxia telangiectasia, a recessive syndrome caused by mutation in the ATM gene.56,57 However, molecular data corroborating this observation were provided after 20 years.58 To date, many truncating splice site mutations and missense variants for ATM have been found and associated with a relative risk of breast cancer of about 2.4.58 Currently there are no data about the role of ATM in men predisposed to breast cancer.

The involvement of BRCA2 in the Fanconi anemia pathway promoted mutation screening of other Fanconi anemia genes functionally linked to BRCA2, such as PALB2, BRIP1, and, more recently, RAD51C.59PALB2 truncating mutations were estimated to be associated with a 2.3-fold increased risk.60PALB2 mutations have now been identified in many countries, with frequencies varying from 0.6% to 2.7% in familial breast cancer cases.61–69 Two founder PALB2 mutations, 1592delT and 2323C > T, were respectively identified in 1% of Finnish and 0.5% of French-Canadian breast cancers unselected for family history.70,71 Interestingly, PALB2 mutations were found in families with both female and male breast cancer cases, suggesting that PALB2 may be involved in male breast cancer risk.60,67 To date, five studies have reported on the frequency of PALB2 mutations in male breast cancer.70,72–75 Overall, PALB2 seems to have a role as a moderate-penetrance gene in male breast cancer to a comparable extent as for female breast cancer. Recently, it has been reported that PALB2 heterozygote mutation carriers were four times more likely to have a male relative with breast cancer.76

Deleterious BRIP1 mutations were initially estimated to confer a twofold increased breast cancer risk and to account for about 1% of BRCA1/2 negative familial/early-onset breast cancer cases, but further studies suggested that the BRIP1 contribution to breast cancer susceptibility might be more limited than initially reported.77–80 Indeed, a total of only eight BRIP1 truncating mutations in 11 BRCA1/2 mutation-negative breast cancer cases from three independent studies have been identified worldwide.77,81,82 Several studies in diverse populations failed to detect truncating mutations.78–80 To date, only one study has investigated the role of BRIP1 in male breast cancer susceptibility, and no evidence was found that germ-line variants in BRIP1 might contribute to male breast cancer predisposition.83 Taken together, these data suggest that the contribution of BRIP1 to breast cancer predisposition in both females and males is less consistent compared with other moderate breast cancer susceptibility genes, such as CHEK2 and PALB2.

Recently, mutations in RAD51C, another gene associated with Fanconi anemia, were identified as breast cancer susceptibility alleles, accounting for 1.3% of female patients from families with at least one case each of breast and ovarian cancer.84 However, further studies did not confirm this frequency.85,86 At present, there is no evidence that RAD51C mutations contribute to male breast cancer susceptibility.87

Low-penetrance breast cancer genes

A polygenic model, in which many genes that confer low risk individually act in combination to confer much larger risk in the population, has been suggested for susceptibility to breast cancer and other common cancers.88 Breast cancers unaccounted for by currently known high-penetrance and moderate-penetrance breast cancer susceptibility genes can be explained by this model. This hypothesis, speculated for years, has only recently been confirmed by multigroup collaborations working in genome-wide association studies performed in a very large series of cases and controls from different countries, in order to increase the power to detect small effects on risk.89,90 Common low-penetrance breast cancer susceptibility single nucleotide polymorphisms have thus far been reported in regions that cover known protein-coding genes, including CASP8, FGFR2, TNRC9, MAP3K1, LSP1, RAD51L1, and ESR1 and in regions such as 8q24, 2q35, 5p12, and 1p11 with no known protein-coding genes (Table 1).90–95 The relative risk conferred by these alleles ranges from 1.07 to 1.26. Overall, these single nucleotide polymorphisms are estimated to account for less than 4% of the familial risk of breast cancer in women.90 Interestingly, many of the alleles are in intronic portions of genes, and often are noncoding regions that may confer susceptibility. This might be explained by the observation that some of these loci are located in regions of linkage disequilibrium that cover different genes, but it is very difficult to establish which of a set of variants in linkage disequilibrium is the most functionally relevant.96 Furthermore, some of these single nucleotide polymorphisms, including CASP8, FGFR2, TOX3, and MAP3K1, could act as modulators of the risk conferred by mutations in the high-penetrance breast cancer susceptibility genes, BRCA1 and BRCA2.97 Recently, a subtle regulatory effect of one allele in the prostate/breast cancer-associated 8q24 block was also demonstrated, which acts as a cis enhancer of the MYC promoter.98 Interestingly, different haplotype blocks within 8q24 were specifically associated with risk of different cancers.99 In particular, four blocks were site-specific (one for breast cancer and three for prostate cancer), and a fifth was a multicancer susceptibility marker because it was associated with a risk of various cancers, including prostate, colon, ovarian, kidney, thyroid, and laryngeal cancer, but not breast cancer.99–101 None of the presently identified loci is directly linked to the DNA repair pathway. Instead, many of the coding loci are in genes somatically mutated in diverse cancers, including breast cancer. Recently, it was observed that genetic germ-line variations in genes encoding for “driver kinases” may influence breast cancer risk, thus suggesting that low-penetrance alleles might be a link between germ-line and somatic alterations in breast cancer.102

Specific single nucleotide polymorphisms seem to be associated with specific clinicopathological features. In particular, loci at FGFR2, MAP3K1, and 2q35 were found to associate specifically with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer.92,103,104 Data are still limited for less common tumor subtypes, such as estrogen receptor-negative or basal-like breast tumors. Whether these loci are associated with the risk of breast cancer in males has not yet been investigated, but an involvement of low-penetrance alleles in male breast cancer susceptibility cannot be excluded and warrants ad hoc studies.

Acquired alterations in breast cancer

Breast cancer development and progression is a multistep process resulting from the accumulation of genetic alterations, such as mutations and copy number variations, and also epigenetic alterations, such as promoter methylation, resulting in aberrant gene expression. The increasing number of deregulated genes subsequently affects important cellular networks, such as cell cycle control, DNA repair, cell adhesion or migration, and differentiation, driving normal breast cells into highly malignant derivatives with metastatic potential. Such alterations can result either in inactivation of tumor suppressor genes (eg, TP53, BRCA1) or activation of proton-cogenes (eg, PIK3CA, MYC), both of which contribute to the malignant state of a transformed cell. Recent landmark studies have shed new light on the genomic landscape of breast cancer. Within a breast tumor there are many infrequently mutated genes and a few frequently mutated genes, resulting in incredible genetic heterogeneity.105,106 The great majority of somatic mutations frequently lie in hotspot regions that might represent targets in cancer therapy. Both genetic and epigenetic alterations are also frequently associated to specific biological and clinicopathological tumor characteristics, allowing the identification of personalized therapies targeting the associated molecular pathways.107–116

Genetic alterations in breast cancer

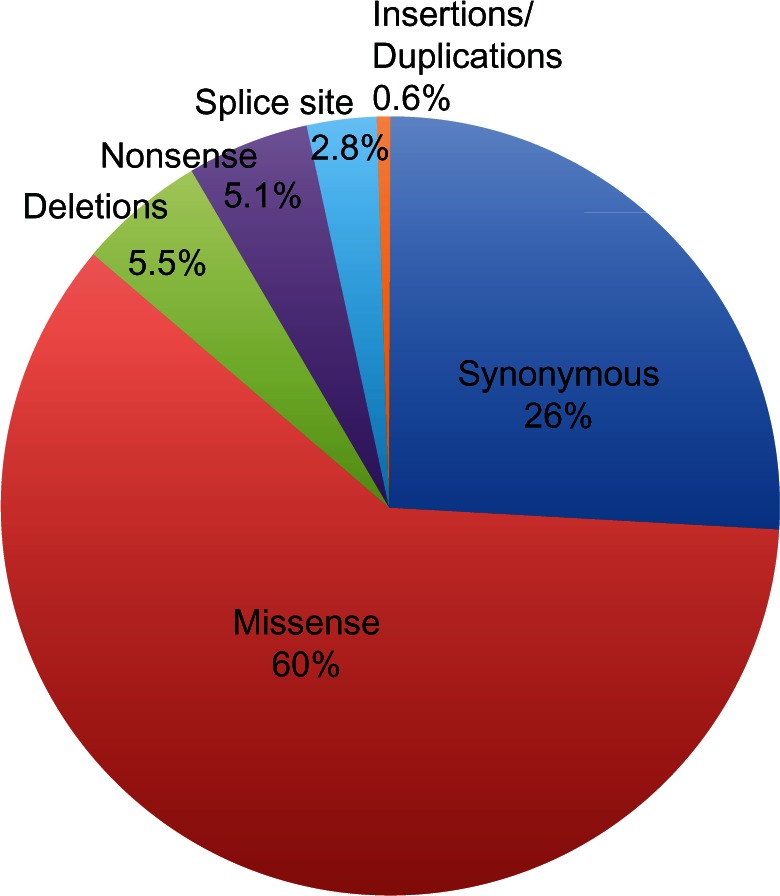

A number of gene and chromosome alterations have been identified in sporadic breast carcinomas. Indeed, the great majority of breast cancer cases are due to solely somatic genetic alterations without germ-line ones.117,118 A heterogeneous set of somatic alterations, including gene amplification, deletion, mutations, and rearrangements, were reported to be involved in the etiology of breast cancer.6 The amount of information on these alterations has been dramatically increased by the introduction of high-throughput molecular cytogenetic approaches. Using large-scale approaches, the sequence of about 18,000 genes has been analyzed in breast cancer cases, and it has been reported that about 10% of these had at least one nonsilent mutation.105 The great majority of alterations are single base substitutions (about 90%), with a prevalence of missense changes (60%, Figure 2). The remainder are somatic mutations resulting in stop codon or splice site alterations, and only a few of these are insertions, deletions, or duplications105 (Figure 2). Somatic mutations found in cancers can be subdivided mainly into two biological classes, ie, “driver” and “passenger” mutations. Driver mutations confer proliferative advantage to tumor cells and are positively selected during cancer development. Passenger mutations are present in the tumor progenitor cells, are biologically neutral, and do not confer a growth advantage.105

Figure 2.

Somatic mutations in breast cancer. The great majority of somatic mutations are single base substitutions, mainly missense mutations; missense changes account for about 60% of somatic alterations; the remaining somatic mutations result in stop codon (5.1%) or in alterations of splice site (2.8%) and only a few percentages of these are insertions, deletions, or duplications (5.6%).

Several studies have shown a bimodal distribution of mutations in breast cancer. It has been proposed that the genomic landscape of breast cancer consists of “mountains” and “hills,” where the mountains correspond to the most frequently mutated genes, specifically PIK3CA and TP53, and the hills consist of a much larger number of less frequently mutated cancer-associated genes (<5%).105,106 Additional to mutations in PIK3CA and P53, alterations in several genes implicated in pathways involved in breast tumorigenesis, including the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt and NF-kB pathways, have been also identified (eg, IKBKB, IRS4, NFKBIA, NFKBIE, NFKB1, PIK3R1, PIK3R4, RPS6KA3, MAP3K1, AKT1, and GATA3 genes).105,119,120 These genes could be considered the hills of the mutational landscape of breast cancer, because their mutation frequencies are lower than for genes considered to be the mountains.

Mutations of the PIK3CA gene are observed in 16%–40% of female breast cancers and in about 18% of male breast cancers.109,121–124PIK3CA mutations are associated with a positive estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor status, nodal involvement, and high histological grade, suggesting that they could be strong prognostic factors in breast cancer.107–110 The great majority (85%) of PIK3CA mutations are in exons 9 and 20, encoding the helical and kinase domains, respectively. The majority of mutations are located in two hot spot regions, including the central helical domain and the COOH terminal kinase domain. The three most common hot spot mutations lead to amino acid changes in the helical domain (E542K and E545K) and in the kinase domain (H1047R).125 In particular E542K, E545K, and H1047R represent 3.6%, 6.2%, and 14.8% of the total PIK3CA mutations in breast cancer, respectively.125

Mutations of the TP53 gene in breast cancer range from 15% to 71% among different populations.126 More than 90% of TP53 mutations reported in breast cancer are located in conservative regions within exons 5 to 8.126,127 More than 2% of all TP53 mutations are represented by three TP53 hot spot mutations, ie, 273 (CGT > CAT), 158 (CGC > CTC), and 248 (CGG > CAG).128 However, an overrepresentation of codon 163 (TAC > TGC) mutation has been observed in breast cancer. Indeed, this codon, rarely mutated in most cancers, accounts for over 2% of all breast cancer mutations. Interestingly, codon 163 is a hot spot for TP53 mutation in breast cancer among BRCA1/2 carriers.127 Overall, TP53 mutations are strongly associated with high histological grade, negative estrogen receptor status, increased global genomic instability, and germ-line BRCA1 mutations.111–113 At least 14 different common polymorphisms have been described in the TP53 gene (IARC p53 data base www.p53.iarc.fr/p53main.html). The most common TP53 polymorphic variants are the16 bp duplication in intron 3 (TP53PIN3) and the TP53 G215C (Arg72Pro). There is some evidence of an association between TP53PIN3 and Arg72Pro variants and elevated breast cancer risk, although some studies suggest a neutral or protective effect for these polymorphisms.129–131 Genotype and haplotype analyses of these two TP53 polymorphisms also revealed that the presence of a specific haplotype carrying the consensus sequence for TP53PIN3 (allele without the 16 bp insertion), and the variant allele for Arg72Pro (72Pro) is associated with an earlier age at onset of breast cancer in BRCA2 mutation carriers.132,133

In addition to nonsynonymous mutations arising from single nucleotide substitutions, several splice variants specific to breast cancer have been reported.134,135 Interestingly, breast cancer-specific alternative splicing is not restricted to splicing defects resulting in loss of protein functions, and may also include modifications that generate proteins with new functions.134

Alternative splicing events can involve breast cancer-specific genes, such as BRCA1, ESR2, and HER2, or genes involved in cell cycle progression, DNA damage response, and spliceosome assembly.134,136–138 The number of known BRCA1 mRNA variants representing aberrant splicing products is relatively high.136 The four predominant mRNA variants with a molecular weight lower than full length BRCA1 are ∆(9,10), ∆(9,10,11q), ∆(11q), and ∆(11). The variants that would be expected to differ the greatest at the functional level from the full length species are those lacking the largest exon 11, containing many functional domains involved in protein-protein interaction.136

Different ESR2 (estrogen receptor β) splice variants have been identified and studies on the function of some of these suggested that they might act as a dominant negative receptor in the estrogen receptor α and β pathways.135,139

A specific splicing variant of HER2 (∆HER2), which causes lack of exon 16 encoding the extracellular domain, has been identified in 9% of breast cancers overexpressing HER2 protein, suggesting that HER2 proteins carrying splicing variants may represent the oncogenic receptor population.137,140

Different alternative splicing events have been identified in which changes in splicing correlate with estrogen receptor status and histological tumor grade.134 Thus, analysis of alternative splicing might provide information about the biology of the tumor.

Genomic instability, such as gene copy number alterations and DNA amplifications, has also been observed frequently in breast cancer. The most commonly amplified regions in breast cancer include 8q24, 11q13, 12q14, 17q11, 17q24, and 20q13, with amplification of genes such as HER2 (15%–20%), EGFR (14%), MYC (15%–20%), CCND1 (15%–20%), ESR1 (20%), and EMSY (7%–13%).114,141,142 Amplification of these regions increases genetic instability in breast cancer and is generally associated with poor prognosis.114

HER2 and EGFR are members of the epidermal growth factor receptor family, and both genes are targets for copy number amplification in breast cancer.143 Amplification of the HER2 gene causes HER2 protein levels that are 10–100 times greater than normal. HER2-positive breast cancers are associated with a worse prognosis and resistance to hormonal therapy144,145EGFR upregulation in breast cancer is not only due to gene amplification but often results from either high polysomy of chromosome 7 or transcriptional induction by the transcription factor YBX1 (Y box binding protein 1).146EGFR amplification is frequently associated with poor prognosis parameters in breast cancer patients, such as large tumor size, high histological grade, high proliferative index, and negative estrogen receptor status.147,148 Moreover, increased EGFR gene copy numbers are observed in triple-negative (estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2 negative) breast cancers together with decreased BRCA1 mRNA expression.149

MYC functions as a transcription factor, regulating up to 15% of all human genes. Although the relationship between amplification and overexpression is not clearly delineated, MYC amplification is significantly correlated with aggressive tumor phenotypes and poor clinical outcomes. MYC amplification is emerging as an important predictor of response to HER2-targeted therapies, and its role in BRCA1-associated breast cancers makes it an important target in basal-like/triple-negative breast cancers.150

Other two genes frequently amplified in breast cancer are ESR1 and CCND1. Amplification of ESR1 is associated with the expression of the estrogen receptor in breast cancer.151 Overall, higher ESR1 gene amplification is found in tumors with CCND1 gene amplification in comparison with tumors without CCND1 gene amplification.151CCND1 amplification occurred preferentially in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer and is associated with reduced overall survival.152–155 Tumors which are sufficiently genetically unstable to develop one gene amplification have increased probability of developing multiple gene amplifications. The coamplification of one or several oncogenes, such as EGFR, ErbB2, CCND1, or ESR1, occurs commonly in breast cancer, and is reported in up to 30% of CCND1-amplified and up to 40% of ErbB2-amplified tumors.114

EMSY amplification in sporadic breast tumors has been shown to be associated with a poor prognosis.141 Amplification of EMSY has been reported in sporadic breast cancer but not in BRCA2-associated breast cancer, suggesting that BRCA2 mutations and EMSY gene amplification may be mutually exclusive.156 Indeed, EMSY protein interacts with the transactivation domain of BRCA2, reducing its activity, and it has been suggested that amplification of EMSY can explain somatic BRCA2 inactivation.156

Recently it has been reported that male breast cancers have a lower frequency of gene copy number alterations than female breast cancers.157 Moreover, different chromosomal regions were found to be altered in male and female breast cancer. Male breast cancer alterations targeted Xp11.23 and 14q13.1 regions in more than 50% of cases. Shared amplified regions between male and female breast cancers are 8q24 (53%), 11q13 (50%), and 17q24 (30%), mapping for MYC, EMSY, and HER2, respectively.117,157 Furthermore, HER2 and CCND1 gene amplification is observed in about 8% and 12% of male breast cancer cases, respectively.158,159

Epigenetic alterations

Epigenetic changes, in particular DNA methylation, are emerging as one of the most important events involved in breast cancer initiation and progression, and there is evidence that DNA methylation may serve as a link between genome and environment. Interestingly, factors that can be modulated by the environment, such as estrogens, elicit epigenetic changes (such as DNA methylation) and this could contribute to breast cancer risk. Furthermore, tumor-specific CpG island hypermethylation profiles are now emerging in breast cancer.7 Tumor-related genes that become hypermethylated may play a significant role in breast cancer, including BRCA1 and hormone response genes, such as estrogen, progesterone, androgen, and prolactin receptors.160 Epigenetic silencing is one of the mechanisms by which mammary epithelial cells repress estrogen receptor expression, leading to the estrogen receptor-negative molecular subtypes of breast cancer.161ESR1 methylation is more common in estrogen receptor-negative than in estrogen receptor-positive tumors, but there is no clear link between ESR1 methylation and estrogen receptor status. It has been suggested that a heterogeneous ESR1 gene methylation pattern may evolve during breast cancer progression and play a role in estrogen receptor-negative recurrences or metastases in patients with estrogen receptor-positive tumors.162 Interestingly, breast tumors with BRCA1 methylation show a high frequency of ESR1 promoter methylation. BRCA1 somatic mutations are extremely rare in sporadic breast cancer, but 9%–13% of these tumors reveal aberrant BRCA1 methylation, especially when loss of heterozygosity occurs at the BRCA1 locus.160BRCA1-associated breast cancers are generally basal-like tumors, and promoter methylation is one mechanism of BRCA1 gene silencing in sporadic basal-like breast cancers. However, there is no significant difference in BRCA1 methylation between sporadic basal-like breast cancers (14%) and matched sporadic nonbasal-like breast cancers (11%). BRCA1 methylation also appears to be similar across distinct breast cancer molecular subtypes (14%–17%) including ductal, mucinous, and lobular breast cancers.163,164

Tumor-specific CpG island hypermethylation profiles are emerging, and the growing list of genes inactivated by promoter hypermethylation in breast cancer include genes involved in evasion of apoptosis (RASSF1A, HOXA5, TWIST1), in cell cycle control (CCND2, p16, RARβ), and tissue invasion and metastasis (CDH1). Tumor suppressor genes, such as GSTP1, RIL, HIN-1, CDH13, APC, and RUNX3, are frequently methylated in breast cancer tissues.115,161,165 These genes are not only hypermethylated in tumor cells, but show increased epigenetic silencing in normal epithelium surrounding the tumor site. Thus, methylation frequently represents an early event in breast cancer tumorigenesis. For example, CCND2, an important regulator of the cell cycle, has been frequently found to be methylated in breast cancer and is also methylated in ductal carcinoma in situ, suggesting that it may represent an early event in tumorigenesis.161 Another gene frequently hypermethylated in breast cancer is RASSF1A. RASSF1A methylation is also an early epigenetic event in breast cancer and is found in ductal carcinoma in situ and in lobular carcinoma in situ.160 Its diverse functions include regulation of apoptosis, growth regulation, and microtubule dynamics during mitotic progression.161

There is some evidence that DNA hypermethylation patterns can identify breast cancer subgroups having distinctive biological properties that could be used for prognostication and for prediction of response to therapy.115,166,167 An association between methylation in five genes, including RARb, CDH1, CCND2, p16, and ESR1, and poor histological differentiation of breast cancer is frequently reported.115,161 Furthermore, distinct epigenetic profiles can be identified when dividing breast tumors into groups based on hormone receptor status.166,168 Differences in methylation status of the promoter region CpG islands of major breast cancer tumor-related genes, such as RASSF1, CCND2, GSTP1, TWIST, RARb, and CDH1, have been found relating to estrogen receptor and HER2 status.115 In particular, methylation of these tumor-related genes resulted in significantly higher estrogen receptor-positive and HER2-positive breast tumors.115,161 On the other hand, double-negative (estrogen receptor-negative, HER2-negative) breast cancers have significantly lower frequencies of RASSF1, GSTP, and APC methylation. Interestingly, epigenetic differences between estrogen receptor-positive and estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer arise early in cancer development and persist during cancer progression.115

Micro RNA

miRNAs are small noncoding, double-stranded RNA molecules involved in post-transcriptional regulation of target genes. Aberrant expressions of miRNA are associated with cancer progression, by acting either as tumor suppressor genes or oncogenes.8,169 Much attention has been paid to deregulation of gene expression through the action of specific miRNA in breast cancer. Microarray studies demonstrated that overall miRNA expression could clearly separate normal versus cancerous breast tissue, with the most significantly deregulated miRNAs being mir-125b, mir-145, mir-21, mir-155, and mir–335.170–172 Interestingly, a large number of miRNAs, overexpressed or underexpressed in breast cancer, are predicted to regulate expression of key breast cancer proteins, such as BRCA1/2, ATM, PTEN, CHEK2, MLH1, P53, and ER.169 Moreover, specific miRNAs, including miRNAs that regulate genes involved in cell proliferation, such as MAPK, RAS, HER2, HER3, and ESR1, have been shown to play a direct role in male breast cancer development.173,174 Indeed, cluster analysis of miRNA expression profiles reveals cancer-specific alterations of miRNA expression in male breast cancer distinct from female breast cancer, such as downregulation of miRNAs that suppress HOXD10, a protein involved in cell proliferation and migration, and vascular endothelial growth factor.173

Significant differences in miRNA expression profiles associated with molecular subtypes of breast cancer and correlated with specific clinicopathological factors, such as estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2 status, emerged in breast cancer.170 Thus, evaluation of the associations between miRNA expression profiles and clinicopathological characteristics may be important to identify distinct breast cancer subgroups and may lead to improvements in the clinical management of breast cancer patients. Indeed, some miRNAs, including mir-21 and mir-145, have been shown to have potential clinical applications as novel biomarkers in the diagnosis and prognosis of breast cancer.175,176 Moreover, miRNAs may act as strong inhibitors of cellular pathways via regulation of entire sets of genes, thus suggesting a possibly great potential for miRNAs in breast cancer prevention and therapeutics.116

Future research directions

Recent advances in technology have shed more light on the complexity of breast cancer biology and have provided data that allow risk estimation for patients with inherited mutations, prognostic and predictive determinations for patients with sporadic breast cancer, and targets for therapies. Recently, loci identified by genome-wide association studies have greatly expanded the list of genes associated with breast cancer risk.

However, evaluation of the functional consequences of low-penetrance alleles in breast cancer risk and their association with breast cancer molecular subtypes and clinicopathological characteristics are still challenging, but are needed for clinical application. Moreover, exploration of the polygenic model proposed for low-penetrance alleles requires further research in diverse and large populations. Overall, despite the remarkable efforts made in recent years, much of the complex landscape of familial breast cancer risk remains unknown, suggesting the need for ongoing efforts in this field.96

The introduction of high-throughput molecular approaches has greatly increased the amount of information on the genomic landscape of breast tumors. Serial analysis of the cancer genome in different phases of its evolution might lead to improved management of the individual breast cancer patient.118

Moreover, studying the global methylation status as well as miRNA expression profiles of different types of tumors will allow the development of profiles unique for breast cancer and its subtypes, staging, and prognostic categories, leading to diagnostic applications and identification of new therapeutic targets.116,171

Conclusion

The identification of breast cancer susceptibility genes, in particular BRCA1 and BRCA2, has changed the management of breast cancer patients with a family history of breast cancer. Several models have been developed, and are currently used to assess the pretest probability of identifying BRCA1/2 germ-line mutations in individuals at risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Moreover, novel therapeutic strategies specific for BRCA1 and BRCA2 cancers are emerging, including crosslinking agents and poly ADP ribose polymerase inhibitors.156

Both genetic and epigenetic acquired alterations are frequently associated with specific biological and clinicopathological tumor characteristics, allowing identification of personalized therapies targeting specific molecular pathways. In particular, a number of compounds, including trastuzumab, lapatinib, and pertuzumab, are currently under clinical evaluation for HER2-targeted therapy.177 However, the majority of HER2-overexpressing breast cancers do not respond to HER2-targeted therapy alone.178 There is evidence showing that combination therapy involving the use of HER2 and endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitors, such as trastuzumab and lapatinib, may have promising results in breast cancer treatment.178 Crosstalk between the endothelial growth factor receptor/HER2 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathways provides a rationale for combining anti-endothelial growth factor receptor/HER2 agents and inhibitors of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mTOR in breast cancer. In addition, DNA methylation as well as miRNAs are currently emerging as interesting candidates for the development of therapeutic strategies against breast cancer. In conclusion, elucidation of the inherited and acquired genetic and epigenetic alterations involved in breast cancer has not only clarified the molecular pathways involved in development and progression of breast cancer itself, but may also have important clinical and therapeutic implications in the management of patients with breast cancer.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Willems PG. Susceptibility genes in breast cancer: more is less? Clin Genet. 2007;72:493–496. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson WF, Jatoi I, Tse J, Rosenberg PS. Male breast cancer: a population-based comparison with female breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:232–239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.8162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin AM, Weber BL. Genetic and hormonal risk factors in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1126–1135. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.14.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson D, Easton D. The genetic epidemiology of breast cancer genes. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2004;9:221–236. doi: 10.1023/B:JOMG.0000048770.90334.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee EY, Muller WJ. Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003236. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stephens PJ, McBride DJ, Lin ML, et al. Complex landscapes of somatic rearrangement in human breast cancer genomes. Nature. 2009;462:1005–1010. doi: 10.1038/nature08645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esteller M. Cancer epigenomics: DNA methylomes and histone-modification maps. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:286–298. doi: 10.1038/nrg2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Croce CM. Causes and consequences of microRNA dysregulation in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:704–714. doi: 10.1038/nrg2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirshfield KM, Rebbeck TR, Levine AJ. Germline mutations and polymorphisms in the origins of cancers in women. J Oncol. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/297671. Epub 2010 Jan 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borresen AL, Andersen TI, Garber J, et al. Screening for germ line TP53 mutations in breast cancer patients. Cancer Res. 1992;52:3234–3236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J, Lindblom P, Lindblom A. A study of the PTEN/MMAC1 gene in 136 breast cancer families. Hum Genet. 1998;102:124–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wooster R, Weber BL. Breast and ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2339–2347. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stratton MR, Rahman N. The emerging landscape of breast cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2008;40:17–22. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nathanson KL, Wooster R, Weber BL. Breast cancer genetics: what we know and what we need. Nat Med. 2001;7:552–556. doi: 10.1038/87876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin AM, Blackwood MA, Antin-Ozerkis D, et al. Germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 in breast-ovarian families from a breast cancer risk evaluation clinic. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2247–2253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.8.2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liebens FP, Carly B, Pastijn A, Rozenberg S. Management of BRCA1/2 associated breast cancer: a systematic qualitative review of the state of knowledge in 2006. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:238–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton M, et al. Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:676–689. doi: 10.1086/301749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1117–1130. doi: 10.1086/375033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen S, Iversen ES, Friebel T, et al. Characterization of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a large United States sample. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:863–871. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank TS, Deffenbaugh AM, Reid JE, et al. Clinical characteristics of individuals with germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2: analysis of 10,000 individuals. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1480–1490. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.6.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ottini L, Rizzolo P, Zanna I, et al. BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation status and clinical-pathologic features of 108 male breast cancer cases from Tuscany: a population-based study in central Italy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;116:577–586. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0194-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papi L, Putignano AL, Congregati C, et al. Founder mutations account for the majority of BRCA1-attributable hereditary breast/ovarian cancer cases in a population from Tuscany, Central Italy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;117:497–504. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durocher F, Shattuck-Eidens D, McClure M, et al. Comparison of BRCA1 polymorphisms, rare sequence variants and/or missense mutations in unaffected and breast/ovarian cancer populations. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:835–842. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.6.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunning AM, Chiano M, Smith NR, et al. Common BRCA1 variants and susceptibility to breast and ovarian cancer in the general population. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:285–289. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiu LX, Yao L, Xue K, et al. BRCA2 N372H polymorphism and breast cancer susceptibility: a meta-analysis involving 44,903 subjects. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:487–490. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0767-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palli D, Falchetti M, Masala G, et al. Association between the BRCA2 N372H variant and male breast cancer risk: a population-based case-control study in Tuscany, Central Italy. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:170. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson D, Easton D. Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Variation in cancer risks, by mutation position, in BRCA2 mutation carriers. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:410–419. doi: 10.1086/318181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson D, Easton D. Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Variation in BRCA1 cancer risks by mutation position. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:329–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phelan CM, Kwan E, Jack E, et al. A low frequency of non-founder BRCA1 mutations in Ashkenazi Jewish breast-ovarian cancer families. Hum Mutat. 2002;20:352–357. doi: 10.1002/humu.10123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Struewing JP, Abeliovich D, Peretz T, et al. The carrier frequency of the BRCA1 185delAG mutation is approximately 1 percent in Ashkenazi Jewish individuals. Nat Genet. 1995;11:198–200. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gudmundsson J, Johannesdottir G, Arason A, et al. Frequent occurrence of BRCA2 linkage in Icelandic breast cancer families and segregation of a common BRCA2 haplotype. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:749–756. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thorlacius S, Olafsdottir G, Tryggvadottir L, et al. A single BRCA2 mutation in male and female breast cancer families from Iceland with varied cancer phenotypes. Nat Genet. 1996;13:117–119. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johannesdottir G, Gudmundsson J, Bergthorsson JT, et al. High prevalence of the 999del5 mutation in Icelandic breast and ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3663–3665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baudi F, Quaresima B, Grandinetti C, et al. Evidence of a founder mutation of BRCA1 in a highly homogeneous population from southern Italy with breast/ovarian cancer. Hum Mutat. 2001;18:163–164. doi: 10.1002/humu.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russo A, Calò V, Bruno L, et al. Is BRCA1-5083del19, identified in breast cancer patients of Sicilian origin, a Calabrian founder mutation? Breast Cancer Res Treat 200911367–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caligo MA, Ghimenti C, Cipollini G, et al. BRCA1 germline mutational spectrum in Italian families from Tuscany: a high frequency of novel mutations. Oncogene. 1996;13:1483–1488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sluiter MD, van Rensburg EJ. Large genomic rearrangements of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes: review of the literature and report of a novel BRCA1 mutation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125:325–349. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0817-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hansen TO, Jønson L, Albrechtsen A, Andersen MK, Ejlertsen B, Nielsen FC. Large BRCA1 and BRCA2 genomic rearrangements in Danish high risk breast-ovarian cancer families. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:315–323. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karhu R, Laurila E, Kallioniemi A, Syrjäkoski K. Large genomic BRCA2 rearrangements and male breast cancer. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30:530–534. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woodward AM, Davis TA, Silva AG, Kirk JA, Leary JA, kConFab Investigators Large genomic rearrangements of both BRCA2 and BRCA1 are a feature of the inherited breast/ovarian cancer phenotype in selected families. J Med Genet. 2005;42:e31. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.027961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walsh T, Casadei S, Coats KH, et al. Spectrum of mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, and TP53 in families at high risk of breast cancer. JAMA. 2006;295:1379–1388. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang T, Lerer I, Gueta Z, et al. A deletion/insertion mutation in the BRCA2 gene in a breast cancer family: a possible role of the Alu-polyA tail in the evolution of the deletion. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2001;31:91–95. doi: 10.1002/gcc.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tournier I, Paillerets BB, Sobol H, et al. Significant contribution of germline BRCA2 rearrangements in male breast cancer families. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8143–8147. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gutiérrez-Enríquez S, de la Hoya M, Martínez-Bouzas C, et al. Screening for large rearrangements of the BRCA2 gene in Spanish families with breast/ovarian cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;103:103–107. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meijers-Heijboer H, van den Ouweland A, Klijn J, et al. Low-penetrance susceptibility to breast cancer due to CHEK2(*)1100delC in noncarriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Nat Genet. 2002;3:55–59. doi: 10.1038/ng879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weischer M, Bojesen SE, Ellervik C, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. CHEK2*1100delC genotyping for clinical assessment of breast cancer risk: meta-analyses of 26,000 patient cases and 27,000 controls. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:542–548. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.5922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neuhausen S, Dunning A, Steele L, et al. Role of CHEK2*1100delC in unselected series of non-BRCA1/2 male breast cancers. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:477–478. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohayon T, Gal I, Baruch RG, Szabo C, Friedman E. CHEK2*1100delC and male breast cancer risk in Israel. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:479–480. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Syrjäkoski K, Kuukasjärvi T, Auvinen A, Kallioniemi OP. CHEK2 1100delC is not a risk factor for male breast cancer population. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:475–476. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Falchetti M, Lupi R, Rizzolo P, et al. BRCA1/BRCA2 rearrangements and CHEK2 common mutations are infrequent in Italian male breast cancer cases. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;110:161–167. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9689-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martinez-Bouzas C, Beristain E, Guerra I, et al. CHEK2 1100delC is present in familial breast cancer cases of the Basque Country. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;103:111–113. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Narod SA, Lynch HT. CHEK2 mutation and hereditary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:6–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Caligo MA, Agata S, Aceto G, et al. The CHEK2 c.1100delC mutation plays an irrelevant role in breast cancer predisposition in Italy. Hum Mutat. 2004;24:100–101. doi: 10.1002/humu.20051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schutte M, Seal S, Barfoot R, et al. Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Variants in CHEK2 other than 1100delC do not make a major contribution to breast cancer susceptibility. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1023–1028. doi: 10.1086/373965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bogdanova N, Enssen-Dubrowinskaja N, Feshchenko S, et al. Association of two mutations in the CHEK2 gene with breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:263–266. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Swift M, Reitnauer PJ, Morrell D, Chase CL. Breast and other cancers in families with ataxia-telangiectasia. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1289–1294. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198705213162101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thompson D, Duedal S, Kirner J, et al. Cancer risks and mortality in heterozygous ATM mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:813–822. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Renwick A, Thompson D, Seal S, et al. ATM mutations that cause ataxia-telangiectasia are breast cancer susceptibility alleles. Nat Genet. 2006;38:873–875. doi: 10.1038/ng1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Levy-Lahad E. Fanconi anemia and breast cancer susceptibility meet again. Nat Genet. 2010;42:368–369. doi: 10.1038/ng0510-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rahman N, Seal S, Thompson D, et al. PALB2, which encodes a BRCA2-interacting protein, is a breast cancer susceptibility gene. Nat Genet. 2007;39:165–167. doi: 10.1038/ng1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tischkowitz M, Xia B, Sabbaghian N, et al. Analysis of PALB2/FANCN-associated breast cancer families. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6788–6793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701724104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cao AY, Huang J, Hu Z, et al. The prevalence of PALB2 germline mutations in BRCA1/BRCA2 negative Chinese women with early onset breast cancer or affected relatives. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;114:457–462. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heikkinen T, Kärkkäinen H, Aaltonen K, et al. The breast cancer susceptibility mutation PALB2 1592delT is associated with an aggressive tumor phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3214–3222. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Papi L, Putignano AL, Congregati C, et al. A PALB2 germline mutation associated with hereditary breast cancer in Italy. Fam Cancer. 2010;9:181–185. doi: 10.1007/s10689-009-9295-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dansonka-Mieszkowska A, Kluska A, Moes J, et al. A novel germline PALB2 deletion in Polish breast and ovarian cancer patients. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sluiter M, Mew S, van Rensburg EJ. PALB2 sequence variants in young South African breast cancer patients. Fam Cancer. 2009;8:347–353. doi: 10.1007/s10689-009-9241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.García MJ, Fernández V, Osorio A, et al. Analysis of FANCB and FANCN/PALB2 Fanconi anemia genes in BRCA1/2-negative Spanish breast cancer families. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113:545–551. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9945-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Balia C, Sensi E, Lombardi G, Roncella M, Bevilacqua G, Caligo MA. PALB2: a novel inactivating mutation in a Italian breast cancer family. Fam Cancer. 2010;9:531–536. doi: 10.1007/s10689-010-9382-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ding YC, Steele L, Chu LH, et al. Germline mutations in PALB2 in African-American breast cancer cases. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:227–230. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1271-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Erkko H, Xia B, Nikkilä J, et al. A recurrent mutation in PALB2 in Finnish cancer families. Nature. 2007;446:316–319. doi: 10.1038/nature05609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Foulkes WD, Ghadirian P, Akbari MR, et al. Identification of a novel truncating PALB2 mutation and analysis of its contribution to early-onset breast cancer in French-Canadian women. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R83. doi: 10.1186/bcr1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sauty de Chalon A, Teo Z, Park DJ, et al. Are PALB2 mutations associated with increased risk of male breast cancer? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;121:253–255. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0673-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Silvestri V, Rizzolo P, Zanna I, et al. PALB2 mutations in male breast cancer: a population-based study in Central Italy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;122:299–301. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0797-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Adank MA, van Mil SE, Gille JJ, Waisfisz Q, Meijers-Heijboer H. PALB2 analysis in BRCA2-like families. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:357–362. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ding YC, Steele L, Kuan CJ, Greilac S, Neuhausen SL. Mutations in BRCA2 and PALB2 in male breast cancer cases from the United States. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:771–778. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1195-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Casadei S, Norquist BM, Walsh T, et al. Contribution to familial breast cancer of inherited mutations in the BRCA2-interacting protein PALB2. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2222–2229. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Seal S, Thompson D, Renwick A, et al. Truncating mutations in the Fanconi anemia J gene BRIP1 are low-penetrance breast cancer susceptibility alleles. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1239–1241. doi: 10.1038/ng1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Karppinen SM, Vuosku J, Heikkinen K, Allinen M, Winqvist R. No evidence of involvement of germline BACH1 mutations in Finnish breast and ovarian cancer families. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:366–371. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00498-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guénard F, Labrie Y, Ouellette G, et al. Mutational analysis of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRIP1/BACH1/FANCJ in high-risk non-BRCA1/BRCA2 breast cancer families. J Hum Genet. 2008;53:579–591. doi: 10.1007/s10038-008-0285-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cao AY, Huang J, Hu Z, et al. Mutation analysis of BRIP1/BACH1 in BRCA1/BRCA2 negative Chinese women with early onset breast cancer or affected relatives. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:51–55. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0052-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lewis AG, Flanagan J, Marsh A, et al. Mutation analysis of FANCD2, BRIP1/BACH1, LMO4 and SFN in familial breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:R1005–R1016. doi: 10.1186/bcr1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.De Nicolo A, Tancredi M, Lombardi G, et al. A novel breast cancer-associated BRIP1 (FANCJ/BACH1) germ-line mutation impairs protein stability and function. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4672–4680. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Silvestri V, Rizzolo P, Falchetti M, et al. Mutation analysis of BRIP1 in male breast cancer cases: a population-based study in Central Italy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:539–543. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1289-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Meindl A, Hellebrand H, Wiek C, et al. Germline mutations in breast and ovarian cancer pedigrees establish RAD51C as a human cancer susceptibility gene. Nat Genet. 2010;42:410–414. doi: 10.1038/ng.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Akbari MR, Tonin P, Foulkes WD, Ghadirian P, Tischkowitz M, Narod SA. RAD51C germline mutations in breast and ovarian cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:404. doi: 10.1186/bcr2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zheng Y, Zhang J, Hope K, Niu Q, Huo D, Olopade OI. Screening RAD51C nucleotide alterations in patients with a family history of breast and ovarian cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;124:857–861. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1095-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Silvestri V, Rizzolo P, Falchetti M, et al. Mutation screening of RAD51C in male breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:404. doi: 10.1186/bcr2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pharoah PD, Antoniou A, Bobrow M, Zimmern RL, Easton DF, Ponder BA. Polygenic susceptibility to breast cancer and implications for prevention. Nat Genet. 2002;31:33–36. doi: 10.1038/ng853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Breast Cancer Association Consortium. Commonly studied single-nucleotide polymorphisms and breast cancer: results from the Breast Cancer Association Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1382–1396. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Easton DF, Pooley KA, Dunning AM, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies novel breast cancer susceptibility loci. Nature. 2007;447:1087–1093. doi: 10.1038/nature05887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cox A, Dunning AM, Garcia-Closas M, et al. A common coding variant in CASP8 is associated with breast cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2007;39:352–358. doi: 10.1038/ng1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Stacey SN, Manolescu A, Sulem P, et al. Common variants on chromosome 5p12 confer susceptibility to estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40:703–706. doi: 10.1038/ng.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Thomas G, Jacobs KB, Kraft P, et al. A multistage genome-wide association study in breast cancer identifies two new risk alleles at 1p11.2 and 14q24.1 (RAD51L1) Nat Genet. 2009;41:579–584. doi: 10.1038/ng.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dunning AM, Healey CS, Baynes C, et al. Association of ESR1 gene tagging SNPs with breast cancer risk. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1131–1139. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Turnbull C, Ahmed S, Morrison J, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies five new breast cancer susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:504–507. doi: 10.1038/ng.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fletcher O, Houlston RS. Architecture of inherited susceptibility to common cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:353–361. doi: 10.1038/nrc2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Antoniou AC, Spurdle AB, Sinilnikova OM, et al. Common breast cancer-predisposition alleles are associated with breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:937–948. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wasserman NF, Aneas I, Nobrega MA. An 8q24 gene desert variant associated with prostate cancer risk confers differential in vivo activity to a MYC enhancer. Genome Res. 2010;20:1191–1197. doi: 10.1101/gr.105361.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ghoussaini M, Song H, Koessler T, et al. Multiple loci with different cancer specificities within the 8q24 gene desert. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:962–966. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wokołorczyk D, Lubiński J, Narod SA, Cybulski C. Genetic heterogeneity of 8q24 region in susceptibility to cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:278–279. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wokolorczyk D, Gliniewicz B, Sikorski A, et al. A range of cancers is associated with the rs6983267 marker on chromosome 8. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9982–9986. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bonifaci N, Górski B, Masojć B, et al. Exploring the link between germline and somatic genetic alterations in breast carcinogenesis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Stacey SN, Manolescu A, Sulem P, et al. Common variants on chromosomes 2q35 and 16q12 confer susceptibility to estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:865–869. doi: 10.1038/ng2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Garcia-Closas M, Chanock S. Genetic susceptibility loci for breast cancer by estrogen receptor status. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:8000–8009. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers. Science. 2007;318:1108–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.1145720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Greenman C, Stephens P, Smith R, et al. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 2007;446:153–158. doi: 10.1038/nature05610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bachman KE, Argani P, Samuels Y, et al. The PIK3CA gene is mutated with high frequency in human breast cancers. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:772–775. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.8.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Saal LH, Holm K, Maurer M, et al. PIK3CA mutations correlate with hormone receptors, node metastasis, and ERBB2, and are mutually exclusive with PTEN loss in human breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2554–2559. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472-CAN-04-3913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Li SY, Rong M, Grieu F, Iacopetta B. PIK3CA mutations in breast cancer are associated with poor outcome. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;96:91–95. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Maruyama N, Miyoshi Y, Taguchi T, Tamaki Y, Monden M, Noguchi S. Clinicopathologic analysis of breast cancers with PIK3CA mutations in Japanese women. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(2 Pt 1):408–414. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jong YJ, Li LH, Tsou MH, et al. Chromosomal comparative genomic hybridization abnormalities in early- and late-onset human breast cancers: correlation with disease progression and TP53 mutations. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004;148:55–65. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(03)00205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Langerød A, Zhao H, Borgan Ø, et al. TP53 mutation status and gene expression profiles are powerful prognostic markers of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R30. doi: 10.1186/bcr1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Holstege H, Joosse SA, van Oostrom CT, Nederlof PM, de Vries A, Jonkers J. High incidence of protein-truncating TP53 mutations in BRCA1-related breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3625–3633. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Al-Kuraya K, Schraml P, Torhorst J, et al. Prognostic relevance of gene amplifications and coamplifications in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8534–8540. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sunami E, Shinozaki M, Sim MS, et al. Estrogen receptor and HER2/neu status affect epigenetic differences of tumor-related genes in primary breast tumors. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R46. doi: 10.1186/bcr2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nana-Sinkam SP, Croce CM. MicroRNAs as therapeutic targets in cancer. Transl Res. 2011;157:216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lerebours F, Lidereau R. Molecular alterations in sporadic breast cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;44:121–141. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bell DW. Our changing view of the genomic landscape of cancer. J Pathol. 2010;220:231–243. doi: 10.1002/path.2645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kan Z, Jaiswal BS, Stinson J, et al. Diverse somatic mutation patterns and pathway alterations in human cancers. Nature. 2010;466:869–873. doi: 10.1038/nature09208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Arnold JM, Choong DY, Thompson ER, et al. Frequent somatic mutations of GATA3 in non-BRCA1/BRCA2 familial breast tumors, but not in BRCA1-, BRCA2- or sporadic breast tumors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119:491–496. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Campbell IG, Russell SE, Choong DY, et al. Mutation of the PIK3CA gene in ovarian and breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7678–7681. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Buttitta F, Felicioni L, Barassi F, et al. PIK3CA mutation and histological type in breast carcinoma: high frequency of mutations in lobular carcinoma. J Pathol. 2006;208:350–355. doi: 10.1002/path.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Dunlap J, Le C, Shukla A, et al. Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase and AKT1 mutations occur early in breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;120:409–418. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0406-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Benvenuti S, Frattini M, Arena S, et al. PIK3CA cancer mutations display gender and tissue specificity patterns. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:284–288. doi: 10.1002/humu.20648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bader AG, Kang S, Zhao L, Vogt PK. Oncogenic PI3K deregulates transcription and translation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:921–929. doi: 10.1038/nrc1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Børresen-Dale AL. TP53 and breast cancer. Hum Mutat. 2003;21:292–300. doi: 10.1002/humu.10174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Olivier M, Hainaut P. TP53 mutation patterns in breast cancers: searching for clues of environmental carcinogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2001;11:353–360. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2001.0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.McKinzie PB, Delongchamp RR, Heflich RH, Parsons BL. Prospects for applying genotypic selection of somatic oncomutation to chemical risk assessment. Mutat Res. 2001;489:47–78. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(01)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Pietsch EC, Humbey O, Murphy ME. Polymorphisms in the p53 pathway. Oncogene. 2006;25:1602–1611. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Damin AP, Frazzon AP, Damin DC, et al. Evidence for an association of TP53 codon 72 polymorphism with breast cancer risk. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30:523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Khadang B, Fattahi MJ, Talei A, Dehaghani AS, Ghaderi A. Polymorphism of TP53 codon 72 showed no association with breast cancer in Iranian women. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2007;173:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Osorio A, Martínez-Delgado B, Pollán M, et al. A haplotype containing the p53 polymorphisms Ins16bp and Arg72Pro modifies cancer risk in BRCA2 mutation carriers. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:242–248. doi: 10.1002/humu.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Martin AM, Kanetsky PA, Amirimani B, et al. Germline TP53 mutations in breast cancer families with multiple primary cancers: is TP53 a modifier of BRCA1? J Med Genet 200340e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Venables JP, Klinck R, Bramard A, et al. Identification of alternative splicing markers for breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9525–9531. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Watson PM, Watson DK. Alternative splicing in prostate and breast cancer. The Open Cancer Journal. 2010;3:62–76. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Orban TI, Olah E. Emerging roles of BRCA1 alternative splicing. Mol Pathol. 2003;56:191–197. doi: 10.1136/mp.56.4.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Castiglioni F, Tagliabue E, Campiglio M, Pupa SM, Balsari A, Ménard S. Role of exon-16-deleted HER2 in breast carcinomas. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2006;13:221–232. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.André F, Michiels S, Dessen P, et al. Exonic expression profiling of breast cancer and benign lesions: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:381–390. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.LaVoie HA, DeSimone DC, Gillio-Meina C, Hui YY. Cloning and characterization of porcine ovarian estrogen receptor β isoforms. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:616–623. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kwong KY, Hung M. A novel splice variant of HER2 with increased transformation activity. Mol Carcinog. 1998;23:62–68. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(199810)23:2<62::aid-mc2>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Rodriguez C, Hughes-Davies L, Vallès H, et al. Amplification of the BRCA2 pathway gene EMSY in sporadic breast cancer is related to negative outcome. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5785–5791. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Ciampa A, Xu B, Ayata G, et al. HER-2 status in breast cancer: correlation of gene amplification by FISH with immunohistochemistry expression using advanced cellular imaging system. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2006;14:132–137. doi: 10.1097/01.pai.0000150516.75567.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Vanden Bempt I, Drijkoningen M, De Wolf-Peeters C. The complexity of genotypic alterations underlying HER2-positive breast cancer: an explanation for its clinical heterogeneity. Curr Opin Oncol. 2007;19:552–557. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3282f0ad8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]