Abstract

As reported in the 2011 World Drug Report, cocaine is likely to be the most problematic drug worldwide in terms of trafficking-related violence and second only to heroin in terms of negative health consequences and drug deaths. Over a period of 60 years, cocaine evolved from the celebrated panacea of the 1860s to outlawed street drug of the 1920s. As demonstrated by the evolution of cocaine use and abuse in the United Kingdom and United States during this time period, cultural attitudes influenced both the acceptance of cocaine into the medical field and the reaction to the harmful effects of cocaine. Our review of articles on cocaine use in the United Kingdom and the United States from 1860 to 1920 reveals an attitude of caution in the United Kingdom compared with an attitude of progressivism in the United States. When the trends in medical literature are viewed in the context of the development of drug regulations, our analysis provides insight into the relationship between cultural attitudes and drug policy, supporting the premise that it is cultural and social factors which shape drug policy, rather than drug regulations changing culture.

Introduction

Cocaine is likely to be the most problematic drug worldwide in terms of trafficking-related violence and second only to heroin in terms of negative health consequences and drug deaths.1 Our review of articles on cocaine use in the United Kingdom and the United States from 1860 to 1920 reveals significant differences in these nations’ initial responses to cocaine use and abuse, leading to subsequent efforts of legal control.

Methods

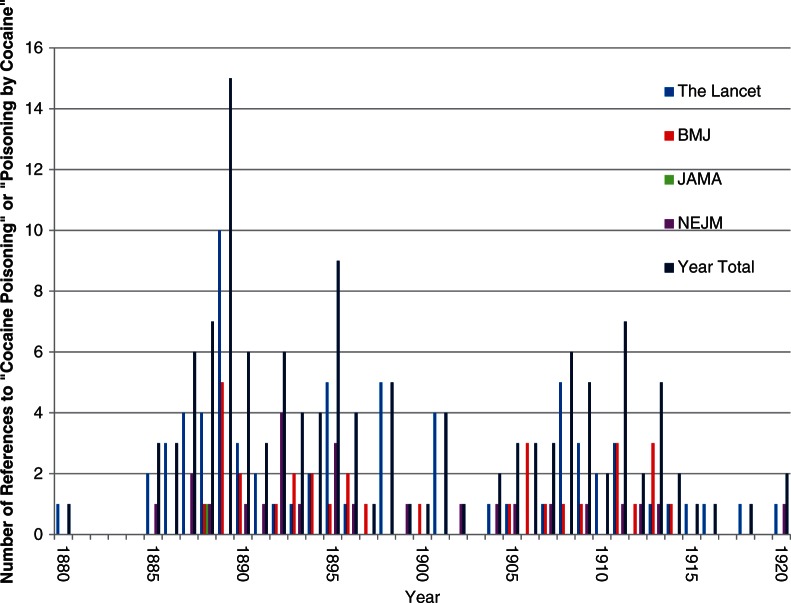

A literature search was carried out using the online databases for The Lancet, British Medical Journal, New England Journal of Medicine and the Journal of the American Medical Association. General trends and cultural attitudes present in the medical field were found by database searches using the search terms ‘cocaine’ and ‘coca’. A systematic search of the databases for The Lancet, British Medical Journal, New England Journal of Medicine and the Journal of the American Medical Association for references to the harmful effects of cocaine was done using the search terms ‘cocaine poisoning’ and ‘poisoning by cocaine’ for the years 1860–1920, inclusive. No results were found for the years 1860–1879, inclusive. Each independent article or letter found using the search terms ‘cocaine poisoning’ and ‘poisoning by cocaine’ was considered a single reference, resulting in a total of 129 independent references found in the time period of 1880–1920, with 70 references in The Lancet, 33 references in the British Medical Journal, 25 references in the New England Journal of Medicine, and 1 reference in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Background: cocaine’s early years

Cocaine is a crystalline alkaloid derived from the leaves of the coca plant, Erythroxylum coca, which is endogenous to South America, Mexico, Indonesia and the West Indies.2 It has been used for centuries by the natives of these countries as a general stimulant, hunger suppressant and an important part of religious rituals. Coca, known in Europe since the Spanish conquest of Peru, remained mostly uninvestigated until, in 1859, Paolo Mantegazza, a prominent Italian physician, published an influential paper on the properties of coca leaf extract.3,4 At approximately the same time, Albert Niemann, a German chemist, isolated cocaine from coca leaves. He published his results in 1860, paving the way for future experimentation with the purified drug.5

Both the United Kingdom and the United States enthusiastically embraced products containing cocaine, often used in the form of a coca leaf extract rather than purified crystals. Cocaine was seen as a miracle drug, with one 1876 article in The Lancet claiming that it ‘has been advocated by one or another in the utmost variety of cases, and were one-tenth part of what has been stated of its effects correct, it would be a panacea for all human ailments – the veritable Elixir of Life’.6

Due to the popularity of cocaine tonics, historian Dr Howard Markel postulates that the world’s first cocaine millionaire was probably Angelo Mariani, a French chemist. Mariani combined ground coca leaves with Bordeaux in the 1860s and marketed his famous tonic wine under the name Vin Mariani. Introduced to the United States in 1863, Vin Mariani was generously prescribed by physicians across Europe and North America. Vin Mariani was used liberally by the public and the elite, including Queen Victoria, Thomas Edison, Ulysses S. Grant and Pope Leo XIII. Pope Leo XIII even awarded Vin Mariani with a Vatican gold medal.7

Cocaine remained popular as a medicinal ingredient in a great many products; however, other than the occasional article prompting the continued exploration of coca’s properties, it nearly dropped out of the medical literature until 1884.

Local anaesthesia: cocaine’s medical miracle

It was in the spring of 1884 when Sigmund Freud, a Viennese neurologist, published his account of cocaine’s physiological effects and potential therapeutic uses in his article titled ‘Über Coca’. He included cocaine’s anaesthetizing effects in his final paragraph (considered by some historians to be more of a postscript), likely not realizing that it was cocaine’s anaesthetizing ability that would make a lasting impression in the medical field.8 Nevertheless, Sigmund Freud’s mention of the anaesthetic properties of cocaine did not escape notice for long.

Carl Koller, an ophthalmology intern at Vienna’s general hospital, used a solution of cocaine hydrochloride for cataract surgery and met with great success. His work was first presented at the international Ophthalmological Congress in September 1884 at Heidelberg, Germany.8 In October and November of 1884, Koller’s work was already being discussed and expanded upon.9,10 It is at this point that the first major distinction between the response of the United Kingdom and the United States becomes apparent.

Two weeks before the publication of Dr Koller’s original paper in Vienna, Americans were informed of his discovery and immediately began testing cocaine in a variety of applications. Consequently, the first response from the United States regarding the use of cocaine as a local anaesthetic was six weeks earlier than the first response from their British counterparts. In addition to its use in ophthalmic surgeries, where cocaine quickly became invaluable, cocaine solutions were popular in laryngeal procedures, otology, genito-urinary surgeries, gynaecology and obstetrics.11

Cocaine as a local anaesthetic reached widespread use by both the Americans and the British. However, in comparison to the Americans, the British proceeded more conservatively in changing their medical practices. Dr Knapp, a physician who compiled all that was written about cocaine in the first decade of its use, was the first to note that the British response was slow and guarded, while the Americans responded with a spirit of receptiveness and progressivism.11,12 These responses to the use of cocaine in medical settings were suggestive of the cultural attitudes that presaged the coming differences in the response to cocaine’s toxic effects.

Cocaine poisoning: impact of UK reticence and US enthusiasm

Comments on the effects of cocaine, such as its ability to increase heart rate and cause pupil dilation, had accompanied even the earliest descriptions of its use. However, most physicians and scientists in the United States and Europe believed cocaine to be safe and non-addictive. It was not until 1887 that belief in the benign nature of cocaine was actively challenged.13 As shown in Figure 1, a survey of the years 1860–1920 in The Lancet, British Medical Journal, New England Journal of Medicine and the Journal of the American Medical Association for references to cocaine poisoning reveals that, when compared with the eager response by the United States and conservative response by the United Kingdom to the discovery of cocaine as an anaesthetic, there was a role reversal when understanding the potential for harm from cocaine use. The earliest mention of poisoning by cocaine occurred in The Lancet in 1880, albeit an animal study report, while it took until 1885 for similar concerns to appear in the New England Journal of Medicine. There was a peak of interest in writing up case studies and treatments for cocaine poisoning in the British medical literature in 1889. While the topic of cocaine poisoning was addressed in American medical literature, with significantly more interest shown in The New England Journal of Medicine than the Journal of the American Medical Association, there was never a dramatic peak of published articles comparable with that of the British publications. It appears as if British caution resulted in higher sensitivity to signs of danger, while American progressivism tended to dampen negative responses.

Figure 1.

References to cocaine poisoning from 1880 to 1920 in The Lancet, the British Medical Journal, the Journal of the American Medical Association and the New England Medical Journal.

The prohibition of cocaine

By the year 1900, cocaine had gone from being the beloved ingredient of the award-winning Vin Mariani to a feared drug holding many people prisoners to addiction. In the United States, it is estimated that 5% of the population was addicted to one or more of cocaine, heroin or morphine at the turn of the 20th century, with the majority being rural, middle-class white women who had been prescribed the drugs by well-meaning physicians.14 With medicinal use of cocaine-containing products culminating in an addiction epidemic in both the United Kingdom and the United States, and increasing numbers of case reports of cocaine poisoning during medical procedures, regulation of cocaine became an impending necessity.

The cultural attitude of caution demonstrated by the United Kingdom in their comparatively slow uptake of cocaine’s medical uses, and in their early and thorough investigation into the harmful effects of cocaine, was also evident in their process of developing legislation to control drug access. The United Kingdom’s Pharmacy Act of 1868 showed a historical willingness to not only appreciate that beneficial drugs often can have harmful effects, but to also accept the need for drug regulations to protect the public from drug abuse.15 In comparison, American progressivism and enthusiasm had resulted in a fast-paced period of increased use of pharmaceutical agents, unaccompanied by any formal drug regulation until decades later. With the historical precedent of the Pharmacy Act of 1868 already in place in the United Kingdom, implementing new drug legislation was not nearly as difficult in the United Kingdom as it was to create similar controls de novo in the United States.

In the United Kingdom, the labelling and sale of products containing cocaine was first regulated under the Poisons and Pharmacy Act of 1908. The Defence of the Realm Act was instituted in 1916 to curb illegal possession of cocaine, prompted by concern over the possession and sale of cocaine by soldiers during the World War I. In 1920, the Dangerous Drugs Act limited the production, import, export, possession, sale or distribution of cocaine to licensed persons. After passing the Dangerous Drugs Act, cocaine use in the United Kingdom was successfully maintained at a low level for the subsequent five to six decades.15

Restricting access to cocaine in the United States was further complicated in that healthcare fell under state instead of federal jurisdiction, meaning that a national law to control access to cocaine would require a constitutional amendment to allow federal interference in healthcare. To avoid legal conflicts, initial attempts to control cocaine use were necessarily piecemeal and indirect.14

The first federal step towards drug control was The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. This act prohibited the sale of adulterated or mislabelled products, serving to decrease drug abuse by curtailing false advertising of drugs. However, it did not outlaw dangerous drugs, such as cocaine, nor did it even restrict the possession and sale of cocaine.14

Success in limiting the sale of cocaine to licensed pharmacists and physicians was finally achieved with the Harrison Tax Act of 1914. Cocaine was added at the last minute by Southern legislators who promoted the post-civil war racial belief that there is a class in society that can control themselves while using alcohol or drugs, and another class that simply cannot. Southern politicians argued that cocaine was a national concern because policemen and physicians reported that cocaine abuse resulted in aggressive, sex-crazed black men who were apt to commit violent crimes and rape innocent white women. It was this carefully timed racist sentiment that forever changed the American society’s view of cocaine from boon to bane. In fact, the perception of cocaine shifted so dramatically that it was the only drug in the Harrison Tax Act which was completely restricted from inclusion in over-the-counter medications.14,16

Today’s use of cocaine

With high rehabilitation costs, relatively frequent overdoses and deaths, and health complications from adulterants and polydrug use, cocaine in the 21st century is a significant burden on healthcare systems worldwide. Recent declines in American cocaine consumption, specifically noted in the population of young drug users, are encouraging. However, even after taking the recent declines into consideration, the United States remains the country with the highest overall cocaine consumption. In comparison, the annual prevalence of cocaine use in the European Union remains less than half of the annual prevalence in the United States, but is double that of a decade earlier. With two-thirds of the European Union’s cocaine users residing in the United Kingdom, Spain and Italy, the cocaine trend in the United Kingdom has been strongly heading upwards.1

Conclusion

Over a period of 60 years, cocaine evolved from the celebrated panacea of the 1860s to outlawed street drug of the 1920s. As demonstrated by the evolution of cocaine use and abuse in the United Kingdom and United States during this time period, cultural attitudes influenced both the acceptance of cocaine into the medical field and the reaction to the harmful effects of cocaine. This influence is shown by publications in medical literature and in the nations’ establishment of regulatory laws.

Now, roughly 100 years after cocaine played a role in the initiation of their drug policies, both nations are facing another potential turning point. The current question is whether or not liberalizing drug laws, in attempts to reduce the amount of criminality involved in drug trafficking, will result in an unwanted increase in drug users. Recent studies by the United Kingdom Drug Policy Commission have concluded that there is little evidence from the United Kingdom, or any other country, that drug policy actually influences the number of drug users or drug dependents. The present day cocaine use trends are likely the result of changing cultural perception of cocaine, not policy.15 Indeed, our analysis of the aetiology of drug laws in the United Kingdom and United States supports the premise that cultural and social factors shape policy, rather than that policy changes culture.

Declarations

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

The research and publication costs will be covered by the History of Medicine Program at the University of Alberta

Guarantor

VW

Contributorship

VW conceived the idea, performed the literature search, and is the main author for this manuscript. DG approved the idea, supervised the project, and contributed in the revision of the manuscript

Acknowledgements

None

Reviewer

Timothy Peters

References

- 1. UNODC. World Drug Report 2011. Malta: United Nations Publication; 2011 June, p.272. Sales No. E.11.XI.10.

- 2.Goldstein RA, DesLauriers C, Burda AM. Cocaine: history, social implications, and toxicity – a review. Dis Mon 2009; 55: 6–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dowdeswell GF. The coca leaf: observations on the properties and action of the leaf of the coca plant (Erythloxylon coca), made in the physiological laboratory of University College. The Lancet 1876 Apr 29; 107: 631–3 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Medical diary of the week. The Lancet 1872 June 1;99:782–746.

- 5.Gootenberg P. Cocaine: Global Histories, London: Routledge, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowdeswell GF. The coca leaf: observations on the properties and action of the leaf of the coca plant (Erythloxylon coca), made in the physiological laboratory of University College. The Lancet 1876 May 6; 107: 664–7 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markel H. An Anatomy of Addiction: Sigmund Freud, William Halsted, and the Miracle Drug Cocaine, New York: Pantheon Books, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markel H. Uber coca: Sigmund Freud, Carl Koller, and cocaine. JAMA 2011; 305: 1360–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ophthalmological society. The Lancet 1884 Oct 18;124:681–3.

- 10.Howe L. The effect of cocaine upon the eye. The Lancet 1884 Nov 22; 124: 911–911 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knapp H. Cocaine and Its Use in Ophthalmic and General Surgery, New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1885 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reviews and notices of books. The Lancet 1885 May 9;125:849–51.

- 13.Mattison JB. Cocaine dosage and cocaine addiction. The Lancet 1887 May 21; 129: 1024–26 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yaroschuk T. Hooked: Illegal Drugs & How They Got That Way - Cocaine, the Third Scourge [television documentary], Boston: The History Channel, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens A, Reuter P. An Analysis of UK Drug Policy, London: UK Drug Policy Commission, 2007 Apr, pp. 108–108 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martensen RL. From papal endorsement to southern vice. JAMA 1996; 276: 1615–1615 [Google Scholar]