Abstract

Objective

To measure the effectiveness of implementing the chronic care model (CCM) in improving HIV clinical outcomes.

Design

Multisite, prospective, interventional cohort study.

Setting

Two urban community health centres in Vancouver and Prince George, BC.

Participants

Two hundred sixty-nine HIV-positive patients (18 years of age or older) who received primary care at either of the study sites.

Intervention

Systematic implementation of the CCM during an 18-month period.

Main outcome measures

Documented pneumococcal vaccination, documented syphilis screening, documented tuberculosis screening, antiretroviral treatment (ART) status, ART status with undetectable viral load, CD4 cell count of less than 200 cells/mL, and CD4 cell count of less than 200 cells/mL while not taking ART compared during a 36-month period.

Results

Overall, 35% of participants were women and 59% were aboriginal persons. The mean age was 45 years and most participants had a history of injection drug use that was the presumed route of HIV transmission. During the study follow-up period, 39 people died, and 11 transferred to alternate care providers. Compared with their baseline clinical status, study participants showed statistically significant (P < .001 for all) increases in pneumococcal immunization (54% vs 84%), syphilis screening (56% vs 91%), tuberculosis screening (23% vs 38%), and antiretroviral uptake (47% vs 77%), as well as increased viral load suppression rates among those receiving ART (72% vs 90%). Stable housing at baseline was associated with a 4-fold increased probability of survival. Aboriginal ethnicity was not associated with better or worse outcomes at baseline or at follow-up.

Conclusion

Application of the CCM approach to HIV care in a marginalized, largely aboriginal patient population led to improved disease screening, immunization, ART uptake, and virologic suppression rates. In addition to addressing underlying social determinants of health, a paradigm shift away from an “infectious disease” approach to a “chronic disease management” approach to HIV care for marginalized populations is strongly recommended.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer à quel point l’adoption du modèle de soins chroniques (MSC) peut améliorer les issues cliniques du SIDA.

Type d’étude

Étude de cohorte prospective, multicentrique et interventionnelle.

Contexte

Deux centres de santé communautaires urbains de Vancouver et Prince Georges, BC.

Participants

Un total de 269 sidatiques séropositifs (18 ans et plus) recevant des soins primaires à l’un des sites de l’étude.

Intervention

Mise en place systématique du MSC sur une période de 18 mois.

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

On a comparé l’état de vaccination contre le pneumocoque, le dépistage pour la syphilis et pour la tuberculose, l’état du traitement antirétroviral (TAR), l’état du TAR avec charge virale indécelable et la numération inférieure à 200 cellules/mL des cellules CD4 avec ou sans TAR, et ce, au début et à la fin d’une période de 36 mois.

Résultats

Dans l’ensemble, 35 % des participants étaient des femmes et 59 % des Autochtones. L’âge moyen était de 45 ans et la plupart des participants avaient déjà utilisé des drogues en injection, voie présumée de transmission du SIDA. Au cours de la période de suivi, 39 participants sont morts et 11 ont été transférés à d’autres soignants. Par rapport à leur état clinique initial, les participants à l’étude ont présenté des augmentations statistiquement significatives (P < ,001 pour l’ensemble des paramètres) de la vaccination contre le pneumocoque (54 % vs 84 %), du dépistage de la syphilis (56 % vs 91 %), du dépistage de la tuberculose (23 % vs 38 %) et de la prise d’antirétroviraux (47 % vs 90 %). Chez ceux qui avaient un logement stable initialement, la probabilité de survie était 4 fois plus grande. L’ethnicité autochtone n’était pas associée à des issues meilleures ou pires au début ou au suivi.

Conclusion

L’adoption du MSC pour le traitement du SIDA dans une population marginalisée composée en grande partie d’Autochtones a entraîné des améliorations dans le dépistage de maladies, la vaccination, le TAR et les taux de suppression virologiques. Non seulement doit-on s’occuper des déterminants sociaux de la santé, mais il est fortement recommandé d’abandonner l’approche de « maladie infectieuse » pour adopter celle de « traitement de maladie chronique » pour traiter le SIDA dans des populations marginalisées.

HIV infection is increasingly viewed as a manageable chronic disease1–3; however, among aboriginal peoples in Canada, HIV-related mortality has remained unacceptably high.4,5 Aboriginal persons in Canada have been shown to be less likely to be diagnosed early,6 less likely to receive effective care,7 and more likely to die while taking antiretroviral treatment (ART)8 or without ever receiving ART9 compared with nonaboriginal Canadians. Aboriginal persons are also disproportionately becoming infected with HIV. Although they represent only 3.8% of the Canadian population, 12.5% of new HIV infections are among aboriginal persons.10 The causes of these health disparities are associated with the social, economic, cultural, and political inequities resulting from the history of colonialism, forced relocation of communities to reservations, and removal of children from their families to be placed into residential schools.11,12 These health inequities are perpetuated by ongoing barriers to accessing medical care including poverty, homelessness, lower levels of educational attainment, addictions, lack of respectful and culturally sensitive services, and racial discrimination.1,13

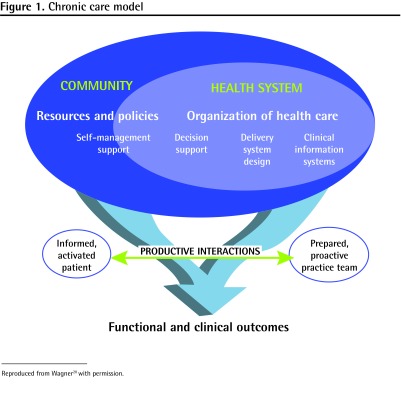

The chronic care model (CCM), developed by Wagner et al,14 has been applied extensively in the management of many chronic diseases including diabetes, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, and nicotine dependence.14–20 This model of care offers a multidimensional approach to chronic disease management through 6 interrelated components (Figure 1).20 This model of care is designed to promote uptake of evidence-based clinical recommendations, enhance clinical teamwork, and empower patients to better manage their own care. It also creates a framework in which patients in need of intervention are easily identified, the quality of care delivery can be objectively examined, and population-based quality improvement initiatives can be evaluated.

Figure 1.

Chronic care model

Reproduced from Wagner20 with permission.

Although recommendations for the uptake of this approach are increasing,1,21 published experiences with the CCM and HIV care remain relatively rare. Veterans Affairs in the United States adopted the CCM approach to improve rates of HIV testing and found some success with increasing the number of individuals tested for HIV.22 Forty-five American Health Resources and Services Administration–sponsored HIV clinics implemented the CCM and found that during an 18-month period, 32 sites showed improvements in clinical parameters including antiretroviral uptake and adherence.23 In western Kenya, a network of HIV clinics has based its ART delivery system on the CCM, incorporating all its key components.24 To our knowledge, no previous studies have implemented the CCM in an inner-city population with a focus on aboriginal persons with HIV. The study objective was to measure the effectiveness of implementing the CCM to improve HIV clinical outcomes.

METHODS

The study used a multisite, prospective, interventional cohort design. The setting for this study was 2 urban community health centres in Vancouver and Prince George, BC, that were both governed by an aboriginal board of directors and were established to provide primary care to the urban aboriginal population. Both study sites strive to deliver health care services in a culturally sensitive manner and address the physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual elements of the patients in the context of their families, communities, and historical traumas. The care teams at both sites differed in their exact configurations, but both had a combination of family physicians, infectious disease specialists, nurses, nurse practitioners, counselors, medical office assistants, case managers or social workers, and aboriginal elders. The Vancouver site is distinguished by its use of HIV-positive peer navigators in its case management program. The Vancouver study site had approximately 4000 active patients, with 50% self-identifying as aboriginal and 10% HIV-positive; the Prince George study site had approximately 1000 active patients, with 80% self-identifying as aboriginal and 6% HIV-positive.

The target populations for this study were known HIV-positive patients who received their primary care at either of the study sites. The inclusion criteria were age older than 18 years and known HIV-positive status. Subjects were recruited when they presented for clinical care during an 18-month period. Ethics review committee decisions required informed written consent from all Vancouver site participants. Demographic data were collected at the time of enrolment. Baseline and subsequent clinical data were collected from the clinics’ electronic medical records. During the enrolment phase of the study, aspects of the CCM were sequentially developed and implemented at each of the study sites. As would be expected, the precise ways in which the model was implemented differed between study sites (Table 1).14 However, both sites implemented all 6 aspects of the CCM. The main outcome measures of interest included the following quality-of-care indicators: rates of pneumococcal vaccination, syphilis screening, tuberculosis screening, ART uptake, and on-treatment viral load suppression; these were calculated for all patients at baseline and at the end of the study period, which was 36 months after the enrolment of the first patient. Rates before and after the implementation of the CCM were compared using χ2 tests or t tests. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board for the Vancouver site and the Northern Health Research Ethics Board for the Prince George site.

Table 1.

The chronic care model with adaptations for HIV care at the Vancouver and Prince George sites in British Columbia: Cells spanning 2 columns indicate the adaptations were made at both sites.

| MODEL COMPONENT | DESCRIPTION | VANCOUVER ADAPTATIONS | PRINCE GEORGE ADAPTATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organization of health care system | Program planning that includes measurable goals for better care | Quality-of-care measures were identified and 90% uptake targets were agreed on by the care team.* Monthly interprofessional HIV rounds were established, in which lists of patients in need of intervention (eg, those with CD4 cell counts < 200 cells/mL and not taking ART) were reviewed. Performance measures were reviewed quarterly and improvement strategies were implemented in a “plan-do-study-act” paradigm | |

| Self-management support | Emphasis on central role patients have in managing their care | Trained clinical staff to provide one-on-one HIV self-management support and developed patient workbooks and handouts | Provided staff and patient education on HIV and hepatitis C in a culturally appropriate manner |

| Decision support | Integration of evidence-based guidelines into daily clinical practice | Developed an electronic HIV flow sheet with embedded clinical guidelines and automated physician reminders.* Medical education sessions were held to review these guidelines | Incorporated HIV clinical guidelines into the existing EMR.* Facilitated on-site infectious disease specialist support |

| Delivery system design | Focus on teamwork and an expanded scope of practice for members to support chronic care | Expanded nursing role to include routine HIV bloodwork monitoring, comorbidity screening, and immunizations. Initiated automatic medical office assistant “call-back” recall system for overdue clinical visits or bloodwork. Created an aboriginal patient–focused HIV-intensive case management team. This team included HIV-positive peer navigators and a local aboriginal elder | Developed HIV outreach nurse position. Provided on-site phlebotomy services. Expanded nursing role to include HIV bloodwork and immunization monitoring, and acting as a liaison with other specialist services. Integration of counseling referrals to aboriginal elder on an as-needed basis |

| Clinical information systems | Functional information system to provide relevant patient data | Implemented an EMR system, which generated a panel listing of HIV patients containing up-to-date relevant clinical data | |

| Community resources and policies | Developing partnerships with community organizations that support and meet patient needs | Developed a “Persons Living with HIV/AIDS” community advisory committee to advise on the development and implementation of the study. Partnership with regional health authority and BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS | Formalized relationships with the local Persons Living with HIV/AIDS organization, needle exchange, and infectious disease specialist. Representatives participated in monthly clinical meetings with patient consent |

ART—antiretroviral therapy, EMR—electronic medical record.

Selection of appropriate clinical guidelines was achieved through a combination of evidence review and a consensus process involving the Vancouver clinic’s medical staff. These clinical guidelines formed the basis for the quality-of-care measures used in this study.

Adapted from Wagner et al.14

RESULTS

During the enrolment period, 269 eligible HIV-positive clinic patients were identified and enrolled. Written consent was obtained for all 211 Vancouver site participants. Of the 269 patients who participated, 11 transferred to other clinics before the end of the study period and 39 patients died. The baseline demographic characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 2. The patients at the Prince George site were more likely to be aboriginal, younger, female, and stably housed. Clinically, patients in Vancouver were more likely to be taking ART and to have CD4 cell counts of 200 cells/mL or greater.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic characteristics and comparison between study sites

| CHARACTERISTIC | TOTAL (N = 269) | VANCOUVER SITE (N = 211) | PRINCE GEORGE SITE (N = 58) | P VALUE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex, n (%) | 94 (35) | 63 (30) | 31 (53) | < .001 |

| Mean age, y | 45 | 46 | 38 | < .001 |

| Aboriginal ethnicity, n (%) | 160 (59) | 115 (55) | 45 (78) | < .001 |

| Stable housing, n (%) | 69 (26) | 44 (21) | 25 (43) | < .001 |

| Mean CD4 cell count, cells/mL | 324 | 333 | 290 | .06 |

| CD4 cell count < 200 cells/mL, n (%) | 81 (30) | 58 (27) | 23 (40) | < .001 |

| Total taking ART, n (%) | 120 (45) | 105 (50) | 15 (26) | < .001 |

| Taking ART and CD4 cell count < 200 cells/mL, n (%) | 36 (13) | 29 (14) | 7 (12) | < .001 |

| Taking ART with an undetectable viral load, n (%)* | 62 (52) | 52 (50) | 10 (67) | < .001 |

| Mean duration of participation in program, y | 2.39 | 2.50 | 1.85 | < .001 |

ART—antiretroviral therapy.

Percentages calculated using the number of patients taking ART.

Table 3 describes the baseline characteristics of those who died versus those who survived the study observation period. Those with stable housing at baseline (defined as living in an apartment, house, or long-term care facility, and excluding those living in single room–occupancy hotel rooms) were significantly more likely to survive, with an odds ratio of 4.83 (95% CI 1.43 to 16.20). Interestingly, aboriginal ethnicity, CD4 cell count, and antiretroviral status were not statistically significant predictors of mortality.

Table 3.

Selected odds ratios of survival for baseline characteristics

| CHARACTERISTIC | SURVIVING (N = 230), N (%) | DIED (N = 39), N (%) | ODDS RATIO OF SURVIVAL (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 79 (34) | 15 (38) | 0.84 (0.41–1.68) |

| Age > 60 y | 8 (3) | 4 (10) | 0.31 (0.09–1.10) |

| Aboriginal ethnicity | 137 (60) | 23 (59) | 1.02 (0.51–2.04) |

| Stable housing | 66 (29) | 3 (8) | 4.83 (1.43–16.20) |

| CD4 cell count < 200 cells/mL | 69 (30) | 12 (31) | 0.96 (0.46–2.01) |

| Taking ART | 105 (46) | 15 (38) | 1.34 (0.67–2.69) |

| Taking ART with an undetectable viral load | 54 (23) | 8 (21) | 1.19 (0.51–2.74) |

ART—antiretroviral therapy.

Table 4 shows the changes in the main outcome measures for the 219 study participants who remained alive and had not transferred other clinics at the end of the study period. Analysis after implementation showed statistically significant (P < .001 for all) increases in pneumococcal immunization (54% vs 84%), syphilis screening (56% vs 91%), tuberculosis screening (23% vs 38%), antiretroviral uptake (47% vs 77%), and viral load suppression rates when taking ART (72% vs 90%). There were no statistically significant associations between aboriginal ethnicity and any of the baseline or end-of-study quality-of-care indicators (data not shown).

Table 4.

Before-and-after comparison of selected HIV quality-of-care measures

| MEASURE | BEFORE (N = 219), N (%) | AFTER (N = 219), N (%) | P VALUE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Documented pneumococcal vaccination | 118 (54) | 183 (84) | < .001 |

| Documented syphilis screening | 123 (56) | 199 (91) | < .001 |

| Documented tuberculosis screening | 51 (23) | 84 (38) | < .001 |

| Taking ART | 104 (47) | 168 (77) | < .001 |

| Taking ART with undetectable viral load | 75 (34) | 151 (69) | < .001 |

| CD4 cell count < 200 cells/mL | 58 (26) | 55 (25) | .640 |

| CD4 cell count < 200 cells/mL and not taking ART | 29 (13) | 15 (7) | < .001 |

ART—antiretroviral therapy.

DISCUSSION

From a biomedical and social perspective, HIV is a complex chronic disease to manage. Adding to the complexity is the reality that HIV disproportionately infects marginalized groups, such as aboriginal Canadians, which contributes to their inferior clinical outcomes. To decrease HIV transmission and improve HIV outcomes, the need to address the social determinants of health, particularly those unique to aboriginal peoples, has long been recognized.12 However, despite calls for interventional research to define “models of good practice that will enable communities to achieve their goal of health equity,”25 substantially less attention has been paid to adapting models of care to address specific aboriginal health issues.

This paper describes the adoption of the CCM to manage HIV care in a marginalized, largely aboriginal patient population at 2 western Canadian inner-city clinics. Adoption of this model of care led to significant improvements in HIV clinical outcomes—specifically, improved disease screening, immunization, ART uptake, and virologic suppression rates. The high virologic suppression rate that was achieved in this study was similar to those of the top-performing clinics in a recent Veterans Affairs medical clinic review.26 Of note, a substantial proportion (14%) of study participants died during the study period, and it was found that stable housing at baseline was associated with a 4-fold increased likelihood of survival. This finding reinforces the importance of addressing housing and other key determinants of health.

It is important to consider that this study was conducted in 2 aboriginal community health centres. Such centres provide care that is informed by the historical traumas experienced by aboriginal peoples in Canada and make explicit efforts to provide care that is culturally appropriate and responsive to the needs of aboriginal peoples. These approaches promote positive and trusting clinical relationships and facilitate access to care for aboriginal persons.

An interesting finding is that at both baseline and the end of the study period there were no significant differences between the aboriginal and nonaboriginal patients with respect to social measures or clinical outcomes. Nonaboriginal patients were originally included in this study to evaluate for such baseline social and clinical inequities. Our interpretation of this was that there might have been an equalizing factor provided by our aboriginal patient–focused clinics and by the similar levels of poverty, drug addiction, and social marginalization among the nonaboriginal patients seen at our clinics. The nonaboriginal patients in this study were included in the final analysis because they shared many of the same social determinants and degrees of marginalization as those of aboriginal ancestry.

Limitations

It is difficult to attribute all of the improvements seen in the patients to the CCM approach, as other factors at the community health centres might have been motivating these changes concurrently. The HIV quality-of-care measures assessed in this study were somewhat limited in scope, and did not include aspects such as patient satisfaction and hospitalization rates. The mortality analysis did not take into account such factors as cause of death, or presence or absence of other comorbidities.

Conclusion

Although published experiences with the CCM in HIV care remain scarce, the findings of this study provide evidence that the CCM can effectively improve the quality of HIV care even in highly marginalized patients. To reduce health inequities and improve HIV outcomes for marginalized aboriginal and nonaboriginal patients, we recommend that health centres shift away from an “infectious disease” model of care and adopt a CCM approach to HIV management and that additional resources also be directed to address inadequate housing and other key social determinants of health. Implementation of the CCM encourages adoption of clinical practice guidelines, empowers care providers to proactively identify patients in need of intervention, and encourages patients to be more active in their self-care. These factors are particularly important among marginalized aboriginal patient groups, who face multiple barriers to accessing care and are at high risk of “falling through the cracks” in the health care system. Further evaluation of the CCM is also required to determine the effect on patient satisfaction, social determinant measures, and rates of morbidity and mortality.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Although HIV is increasingly recognized as a manageable chronic illness in resource-rich countries, HIV-related morbidity and mortality remains unacceptably high among aboriginal persons living in Canada.

Adoption of the chronic care model in 2 urban community health centres led to significant improvements in HIV clinical outcomes. Specifically, there was improved disease screening, immunization, antiretroviral uptake, and virologic suppression rates (P < .001). There were no significant differences between the aboriginal and nonaboriginal patients with respect to social measures and clinical outcomes.

Implementation of the chronic care model encourages adoption of clinical practice guidelines, empowers care providers to proactively identify patients in need of intervention, and encourages patients to be more active in their self-care.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Malgré le fait que le SIDA est de plus en plus considéré comme une maladie chronique traitable dans les pays riches, les taux de morbidité et de mortalité demeurent beaucoup trop élevés chez les Autochtones vivant au Canada.

L’adoption du modèle de soins chroniques dans 2 centres communautaires urbains a entraîné une amélioration significative des issues cliniques liées au SIDA. Plus précisément, on a noté une amélioration du dépistage des maladies, de la vaccination, de la prise d’antirétroviraux et des taux de suppression virologiques (P < ,001). Il n’y avait pas de différence significative entre les Autochtones et les non-Autochtones pour ce qui est des paramètres sociaux et des issues cliniques.

La mise en place du modèle de soins chroniques favorise l’adoption des directives de pratique clinique, permet aux soignants d’identifier de façon proactive les patients qui requièrent une intervention et encourage les patients à prendre en main leur santé.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

Drs Tu and Belda developed the study protocol, coordinated the intervention and data collection, analyzed the data, and developed the manuscript. Ms Littlejohn developed the study protocol, coordinated and developed the study intervention, and developed the manuscript. Ms Pedersen reviewed the literature, analyzed the data, and developed the manuscript. Mr Valle-Rivera performed the data extraction and analysis, and developed the manuscript. Dr Tyndall developed the study protocol, contributed to the development of the study intervention and research design, analyzed the data, and developed the manuscript.

Competing interests

Support for this research project was provided by the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority, the Interior Health Authority, and an open research grant from Pfizer Global Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Swendeman D, Ingram BL, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Common elements in self-management of HIV and other chronic illnesses: an integrative framework. AIDS Care. 2009;21(10):1321–34. doi: 10.1080/09540120902803158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabkin M, Nishtar S. Scaling up chronic care systems: leveraging HIV programs to support noncommunicable disease services. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(Suppl 2):S87–90. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821db92a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yehia BR, Gebo KA, Hicks PB, Korthuis PT, Moore RD, Ridore M, et al. Structures of care in the clinics of the HIV Research Network. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(12):1007–13. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Public Health Agency of Canada . Understanding the HIV/AIDS epidemic among aboriginal peoples in Canada: the community at a glance. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tjepkema M, Wilkins R, Senécal S, Guimond É, Penney C. Mortality of urban aboriginal adults in Canada, 1991–2001. Chronic Dis Can. 2010;31(1):4–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood E, Montaner JS, Li K, Zhang R, Barney L, Strathdee SA, et al. Burden of HIV infection among aboriginal injection drug users in Vancouver, British Columbia. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(3):515–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114595. Epub 2008 Jan 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.BC Aboriginal HIV/AIDS Task Force . The red road: pathways to wholeness. An aboriginal strategy for HIV and AIDS in BC. Vancouver, BC: BC Aboriginal HIV/AIDS Task Force; 1999. Available from: www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/1999/red-road.pdf. Accessed 2013 Apr 26. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lima VD, Kretz P, Palepu A, Bonner S, Kerr T, Moore D, et al. Aboriginal status is a prognostic factor for mortality among antiretroviral naïve HIV-positive individuals first initiating HAART. AIDS Res Ther. 2006;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood E, Montaner JS, Tyndall MW, Schechter MT, O’Shaughnessy MV, Hogg RS. Prevalence and correlates of untreated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection among persons who have died in the era of modern antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2003;188(8):1164–70. doi: 10.1086/378703. Epub 2003 Oct 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Public Health Agency of Canada, Centre for Infectious Disease Prevention and Control, Surveillance and Risk Assessment Division . Summary: estimates of HIV prevalence and incidence in Canada, 2008. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2008. Available from: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/aids-sida/publication/survreport/estimat08-eng.php. Accessed 2011 Nov 16. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adelson N. The embodiment of inequity: health disparities in aboriginal Canada. Can J Public Health. 2005;96(Suppl 2):S45–61. doi: 10.1007/BF03403702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King M, Smith A, Gracey M. Indigenous health part 2: the underlying causes of the health gap. Lancet. 2009;374(9683):76–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60827-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monette LE, Rourke SB, Gibson K, Bekele TM, Tucker R, Greene S, et al. Inequalities in determinants of health among aboriginal and Caucasian persons living with HIV/AIDS in Ontario: results from the Positive Spaces, Healthy Places Study. Can J Public Health. 2011;102(3):215–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03404900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner EH, Davis C, Schaefer J, Von Korff M, Austin B. A survey of leading chronic disease management programs: are they consistent with the literature? Manag Care Q. 1999;7(3):56–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warm EJ. Diabetes and the chronic care model: a review. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2007;3(4):219–25. doi: 10.2174/1573399076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barr VJ, Robinson S, Marin-Link B, Underhill L, Dotts A, Ravensdale D, et al. The expanded chronic care model: an integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the chronic care model. Hosp Q. 2003;7(1):73–82. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2003.16763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlini BH, Schauer G, Zbikowski S, Thompson J. Using the chronic care model to address tobacco in health care delivery organizations: a pilot experience in Washington state. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11(5):685–93. doi: 10.1177/1524839908328999. Epub 2009 Jan 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams SG, Smith PK, Allan PF, Anzueto A, Pugh JA, Cornell JE. Systematic review of the chronic care model in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevention and management. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(6):551–61. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.6.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McEvoy P, Barnes P. Using the chronic care model to tackle depression among older adults who have long-term physical conditions. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2007;14(3):233–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract. 1998;1(1):2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Self-management and the chronic care model. HRSA CAREaction. 2006;1:1–8. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, HIV/AIDS Bureau; 2006. Available from: ftp://ftp.hrsa.gov//hab/march2006.pdf. Accessed 2013 Apr 26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goetz MB, Bowman C, Hoang T, Anaya H, Osborn T, Gifford AL, et al. Implementing and evaluating a regional strategy to improve testing rates in VA patients at risk for HIV, utilizing the QUERI process as a guiding framework: QUERI Series. Implement Sci. 2008;3:16. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherer R, O’Neill J, Barini-Garcia M, Bass P, Becker S, Boushon B, et al. Testing innovative quality improvement (QI) methods for HIV care in 10,000 patients (pts) in the US: the HRSA/IHI HIV Collaborative (abstract no. B10641). Paper presented at: XIV International AIDS Conference; 2002 Jul 7–12; Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wools-Kaloustian K, Kimaiyo S. Extending HIV care in resource-limited settings. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2006;3(4):182–6. doi: 10.1007/s11904-006-0014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King M. Chronic diseases and mortality in Canadian aboriginal peoples: learning from the knowledge. Chronic Dis Can. 2010;31(1):2–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Backus LI, Boothroyd DB, Phillips BR, Belperio PS, Halloran JP, Valdiserri RO, et al. National quality forum performance measures for HIV/AIDS care: the Department of Veterans Affairs’ experience. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(14):1239–46. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]