Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effect of the Provider and Patient Reminders in Ontario: Multi-Strategy Prevention Tools (P-PROMPT) reminder and recall system and pay-for-performance incentives on the delivery rates of cervical and breast cancer screening in primary care practices in Ontario, with or without deployment of nurse practitioners (NPs).

Design

Before-and-after comparisons of the time-appropriate delivery rates of cervical and breast cancer screening using the automated and NP–augmented strategies of the P-PROMPT reminder and recall system.

Setting

Southwestern Ontario.

Participants

A total of 232 physicians from 24 primary care network or family health network groups across 110 different sites eligible for pay-for-performance incentives.

Interventions

The P-PROMPT project combined pay-for-performance incentives with provider and patient reminders and deployment of NPs to enhance the delivery of preventive care services.

Main outcome measures

The mean delivery rates at the practice level of time-appropriate mammograms and Papanicolaou tests completed within the previous 30 months.

Results

Before-and-after comparisons of time-appropriate delivery rates (< 30 months) of cancer screening showed the rates of Pap tests and mammograms for eligible women significantly increased over a 1-year period by 6.3% (P < .001) and 5.3% (P < .001), respectively. The NP-augmented strategy achieved comparable rate increases to the automated strategy alone in the delivery rates of both services.

Conclusion

The use of provider and patient reminders and pay-for-performance incentives resulted in increases in the uptake of Pap tests and mammograms among eligible primary care patients over a 1-year period in family practices in Ontario.

Résumé

Objecti

Évaluer l’effet du projet Provider and Patient Reminder in Ontario Multi Strategy Prevention Tools (P-PROMPT), un système utilisant des mémos et des rappels ainsi que des mesures financières incitatives basées sur le rendement, sur le taux de dépistage des cancers du col utérin et du sein dans des cliniques de soins primaires de l’Ontario, avec ou sans recours à des infirmières praticiennes (IP).

Type d’étude

Comparaison des taux de dépistage en temps opportun des cancers du col utérin et du sein avant et après l’addition d’IP et l’utilisation des stratégies automatisées du système de mémos et de rappels P-PROMPT.

Contexte

Le sud-ouest de l’Ontario.

Participants

Un total de 232 médecins et de 24 réseaux de soins primaires ou de groupes de réseaux de santé familiale couvrant 110 sites différents admissibles au système de rémunération basé sur le rendement.

Interventions

Le projet P-PROMPT associe des mesures incitatives financières basées sur le rendement à des rappels aux soignants et aux patientes et au recours à des IP dans le but d’augmenter la prestation de services de santé préventifs.

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

Taux moyen de mammographies et de tests de Papanicolaou effectués en temps opportun dans les cliniques au cours des 30 mois précédents.

Résultats

La comparaison des taux de dépistage du cancer en temps opportun (moins de 30 mois) a montré une augmentation de 6,3 % du taux de Pap tests (P < ,001) et de 5,3 % du taux de mammographies (P < ,001) sur une période d’un an chez les femmes admissibles. Le recours à un nombre accru d’IP a entraîné des augmentations comparables à celles de la stratégie automatisée seule, et ce, pour les 2 types de dépistage.

Conclusion

L’utilisation de rappels à l’intention des soignants et des patientes et de mesures financières incitatives basées sur le rendement a entraîné une augmentation de la prestation des Pap tests et des mammographies chez des patientes admissibles des soins primaires sur une période d’un an dans des cliniques de médecine familiale de l’Ontario.

Preventive care service delivery rates in primary care settings in Ontario continue to be lower than recommended. Data from Cancer Care Ontario indicate that about 66% of women in Ontario between the ages of 50 and 69 years report having received preventive screening mammograms within the past 2 years.1 The 2001 Canadian Community Health Survey provides further support for the need to increase the uptake of preventive care services. The survey data indicate that fewer than half (47%) of eligible women received mammograms within the recommended 2-year interval, and fewer than three-quarters (71%) of eligible women reported receiving Papanicolaou tests within the previous 3 years.2 The 2011 Canadian Breast Cancer Screening Initiative has set targets for breast cancer screening participation rates at a minimum of 70% of the female population between the ages of 50 and 69 years.3 Currently, there are no national targets in Canada for participation in cervical cancer screening.

One strategy that effectively increases the delivery of preventive care services is the use of patient and physician reminder and recall systems for preventive care services such as cervical cancer screening, mammograms, and immunizations.4–6 Non-randomized trials have shown that reminders, whether for patients or physicians, can increase the rate of screening,7 and that patient-specific, personalized invitations are more effective than generic reminders.8 Letter reminders to patients have become an integral component of Iceland’s cervical screening program, which achieved an 84% reduction in cervical cancer mortality over the 17-year period from 1965 to 1982.9 A 2002 Cochrane review concluded that there is evidence to support the use of invitation letters to increase cervical screening,10 while another review looked at strategies for increasing participation rates in breast screening programs.11 The latter review identified 5 effective strategies for inviting women to attend community breast cancer screening services: letter of invitation (odds ratio [OR] = 1.66), telephone call (OR = 1.94), invitation letter plus telephone call (OR = 2.53), training activities plus direct reminders (OR = 2.46), and mailed educational material (OR = 2.82).11

There is evidence that nurse practitioners (NPs) are effective for providing health promotion and disease prevention services in primary care settings, especially for underserviced and marginalized populations.12 A meta-analysis of NPs in primary care that compared the uptake of services provided by physicians with those provided by NPs found that for health promotion activities, NPs scored significantly higher, meaning that they implemented more health promotion–related activities with their clients than physicians did (effect size 0.56; 95% CI 0.26 to 0.85; P < .001).13

In 2000, the Canadian federal government established the Primary Health Care Transition Fund (PHCTF) to support provincial and territorial efforts to introduce new approaches to primary health care delivery.14 One of the 5 goals of the PHCTF initiatives was to increase the emphasis on health promotion, disease and injury prevention, and chronic disease management.

The preventive care management program, an integral part of Ontario’s primary care renewal program, explicitly recognized the need to improve delivery of preventive care services by offering a progressive range of annual performance payments and management fees to physicians practising under newly created primary care network or family health network models.15 In 2005, the following 4 preventive care services, all based on grade A and B recommendations of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care,16 were included in the program: annual autumn influenza vaccination for patients 65 years of age and older; biennial Pap tests for women aged 35 to 69 years; biennial mammography for women aged 50 to 69 years; and completion of 5 recommended immunizations for children before 2 years of age. The annual bonus payments increase incrementally to a maximum of $2200 for delivery rates as follows: 75% or more for mammography screening, 80% or more for Pap tests and for annual influenza vaccination, and 95% for childhood immunizations. In addition, each physician was eligible to claim a management fee of $6.86 for each overdue patient contacted by reminder letter plus a telephone call, which resulted in the overdue service being delivered. The development and implementation of the actual strategy to improve the delivery of preventive care services, including its administration, was left to the discretion of the individual practices.

The Provider and Patient Reminders in Ontario: Multi-Strategy Prevention Tools (P-PROMPT) project was funded by PHCTF to develop and evaluate a large-scale demonstration project aimed at increasing delivery of 4 targeted preventive care services by the following means: the newly created models of primary care eligible for pay-for-performance preventive incentives; the preventive care management program; the recall and reminder systems; and the deployment of NPs to enhance delivery of preventive care services.

We hypothesize that the reminder system will be most effective with providers and patients who “forget,” while NPs will more effectively address marginalized or vulnerable patients who are inadequately served by the opportunistic approach alone. The overall objective of our study was to evaluate the effect of the P-PROMPT reminder and recall system, which applied automated and NP-augmented strategies, and pay-for-performance incentives on the delivery rates of cervical and breast cancer screening within primary care network or family health network group models in Ontario. The effect of P-PROMPT on influenza vaccination rates has been reported earlier,17 and its effect on the childhood immunization rates could not be determined because reliable and timely administrative data were not available.

METHODS

Seventy-three percent (246 of 335) of the family physicians in primary care network or family health network groups in southwestern Ontario eligible to participate in the preventive care management program agreed to take part in the P-PROMPT demonstration project. The participants included 90 physicians from 8 primary care network practices and 156 physicians from 16 family health network practices located in southwestern Ontario, with more than 350 000 patients rostered to their care. The core reminder and recall intervention was made available to all participating practices. In addition, each of 6 primary care network or family health network groups, consisting of 5 to 10 physicians each, also received the services of an NP who focused on delivering the project’s targeted preventive services while working within the full scope of NP practice. The main criteria for allocating NPs to practices were logistic: availability of NPs in different locations and ability of practices to accommodate additional staff. This meant that our original hypothesis that using the special training and skills of NPs would enhance screening rates among marginalized or vulnerable patients could not be adequately tested.

The main activities of the project consisted of obtaining, integrating, and regularly updating electronic roster data of patients from participating practices, including identification of ineligible patients or those eligible patients who received the targeted services elsewhere. Acting as the physicians’ agent, P-PROMPT obtained repeatedly over time the dates of the most recent mammograms from the Ontario Ministry of Health billing data and from the Ontario Breast Screening Program of Cancer Care Ontario. Likewise, P-PROMPT obtained the dates of the most recent Pap tests from CytoBase, a consortium of the main laboratories in Ontario (which captures more than 90% of total Pap tests conducted in the province). These data were subsequently merged with rosters of eligible patients in order to identify and generate physician reminder lists of due and overdue patients. These patient lists were made available on a secure, continually updated and interactive P-PROMPT website. Patient reminder letters were then created using text that was approved or modified by each physician, generated on physician letterhead, individually addressed, signed with the physician’s electronic signature, and mailed along with educational material about the relevant preventive care procedure. Additional activities included calculating annual preventive care bonuses, as well as management fees, for successful patient reminder letters.

Efforts to increase screening rates among “hard-to-reach” (never screened) patients included sending patient educational materials produced by the Ontario Breast Screening Program and Cancer Care Ontario to all patients receiving their second reminder letter for a Pap test or mammogram. The information was available in numerous languages, and family physicians were given the option of selecting the language best suited for each patient. In the NP-augmented intervention, NPs developed various proactive strategies, including reminder telephone calls, targeting marginalized and vulnerable populations.

Descriptive statistics were calculated to describe characteristics of participating practices and eligible patients. In order to determine changes in the delivery rates, the number of up-to-date women within each practice was divided by the total number of eligible women—for both mammograms and Pap tests—for the 2 fiscal years ending 2005 and 2006. Following the preventive care management program guidelines, the mean time-appropriate rates for mammograms and Pap tests were defined as having at least 1 screening test done within the previous 30 months.

Repeated-measures ANOVA (analysis of variance) tests were used to compare changes in the mean rates at the practice level before and after the P-PROMPT implementation and between the automated and NP-augmented strategies. McNemar tests were used to analyze within-practice changes in the top performance category. Only practices with valid data in both fiscal years were included in the analysis. All analyses were conducted at the practice rather than at the individual patient level and were carried out with SPSS, version 17.0.0, and a significance level of .05 (2-sided) was used in all statistical tests. The study was approved by the Hamilton Health Sciences and Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Board.

RESULTS

At the start of the 2004 to 2005 fiscal year, there were 232 physicians participating in the project for whom the 2005 to 2006 data were also later available. These physicians had a total of 83 101 female patients aged 35 to 69 years eligible for biennial Pap tests, and 39 780 female patients aged 50 to 69 years eligible for biennial mammography screening. Because some practices were still actively rostering new patients, the roster size for these 2 services increased by 1704 women (to 86 075) for a Pap test and by 1873 women (to 41 767) for mammography screening in the 2005 to 2006 fiscal year (Table 1). The profile of the 232 physicians with valid data in both fiscal years was comparable both to the remaining physicians and to the general profile of family physicians in Canada in terms of sex, year of graduation from medical school, and practice setting (urban or rural).18

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating physicians and practices

| CHARACTERISTICS | VALUE |

|---|---|

| Physicians | |

| Male sex, % | 61.6 |

| Canadian graduates, % | 83.0 |

| Mean (SD) graduation year | 1983 (9) |

| Academic affiliation, % | 10.9 |

| CFPC Certification, % | 70.3 |

| Urban practice, % | 85.6 |

| Mammography | |

| 2004–2005 total roster size* | 39 780 |

| • Ineligible patients | 501 |

| • Eligible patients | 39 279 |

| 2005–2006 total roster size* | 41 767 |

| • Ineligible patients | 615 |

| • Eligible patients | 41 152 |

| Papanicolaou test | |

| 2004–2005 total roster size* | 83 101 |

| • Ineligible patients | 8813 |

| • Eligible patients | 74 288 |

| 2005–2006 total roster size* | 86 075 |

| • Ineligible patients | 10 083 |

| • Eligible patients | 75 992 |

CFPC—College of Family Physicians of Canada.

Roster size increased because some practices were still actively rostering new patients. All male patients and all women outside the respective target age ranges are excluded from these totals.

After acquiring and merging relevant data from both the enrolled family practices and the external databases, approval was received from the practices to create and mail the first and second reminder letters to women who were due or overdue for Pap tests (23 889 and 6740, respectively) and for mammograms (12 877 and 4280, respectively) in 2005 to 2006 (Table 1).

There was a statistically significant increase in the mean time-appropriate delivery rates for both preventive care services after 1 year of the P-PROMPT intervention—an overall 6.3% (95% CI 5.1% to 7.5%) increase in Pap test rates (from 68.9% to 75.2%, F1,230 = 73.7, P < .001) and a 5.3% (95% CI 4.2% to 6.4%) increase in time-appropriate mammography screening rates (from 70.0% to 75.4%, F1,230 = 56.4, P < .001). The interactions between time (before and after) and type of strategy (NP-augmented vs automated) were not statistically significant for Pap tests or mammography screening (F1,230 = 0.6, P = .45; F1,230 = 0.3, P = .92, respectively) (Table 2). Overall, the absolute screening rate across all participating practices increased from 68.7% (51 049 of 74 288) to 75.2% (57 363 of 76 316) for cervical cancer, and from 69.5% (27 308 of 39 279) to 74.8% (30 949 of 41 357) for breast cancer.

Table 2.

Mean (SD) percentage of preventive care services delivered before and after P-PROMPT implementation

| PREVENTIVE CARE SERVICE | BEFORE P-PROMPT, 2004–2005, MEAN (SD) | AFTER P-PROMPT, 2005–2006, MEAN (SD) | DIFFERENCE (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mammography* | |||

| • All physicians (N = 232) | 70.04 (12.96) | 75.35 (12.46) | 5.31 (4.24–6.38) |

| • Automated strategy (n = 191) | 68.94 (13.41) | 74.23 (13.13) | 5.29 (4.06–6.51) |

| • NP-augmented strategy (n = 41) | 75.14 (9.14) | 80.57 (6.60) | 5.43 (3.33–7.51) |

| Papanicolaou test† | |||

| • All physicians (N = 232) | 68.90 (18.00) | 75.19 (18.37) | 6.29 (5.12–7.45) |

| • Automated strategy (n = 191) | 67.54 (18.99) | 73.62 (19.58) | 6.08 (4.71–7.44) |

| • NP-augmented strategy (n = 41) | 75.24 (10.48) | 82.50 (7.77) | 7.26 (5.38–9.15) |

NP—nurse practitioner, P-PROMPT—Provider and Patient Reminders in Ontario: Multi-Strategy Prevention Tools.

2004–2005 to 2005–2006, F1,230 = 56.4, P < .001; automated vs NP-augmented, F1,230 = 9.5, P = .002; interaction (time × strategy), F1,230 = 0.3, P = .922.

2004–2005 to 2005–2006, F1,230= 73.7, P < .001; automated vs NP-augmented, F1,230 = 7.7, P = .006; interaction (time × strategy), F1,230 = 0.6, P = .445.

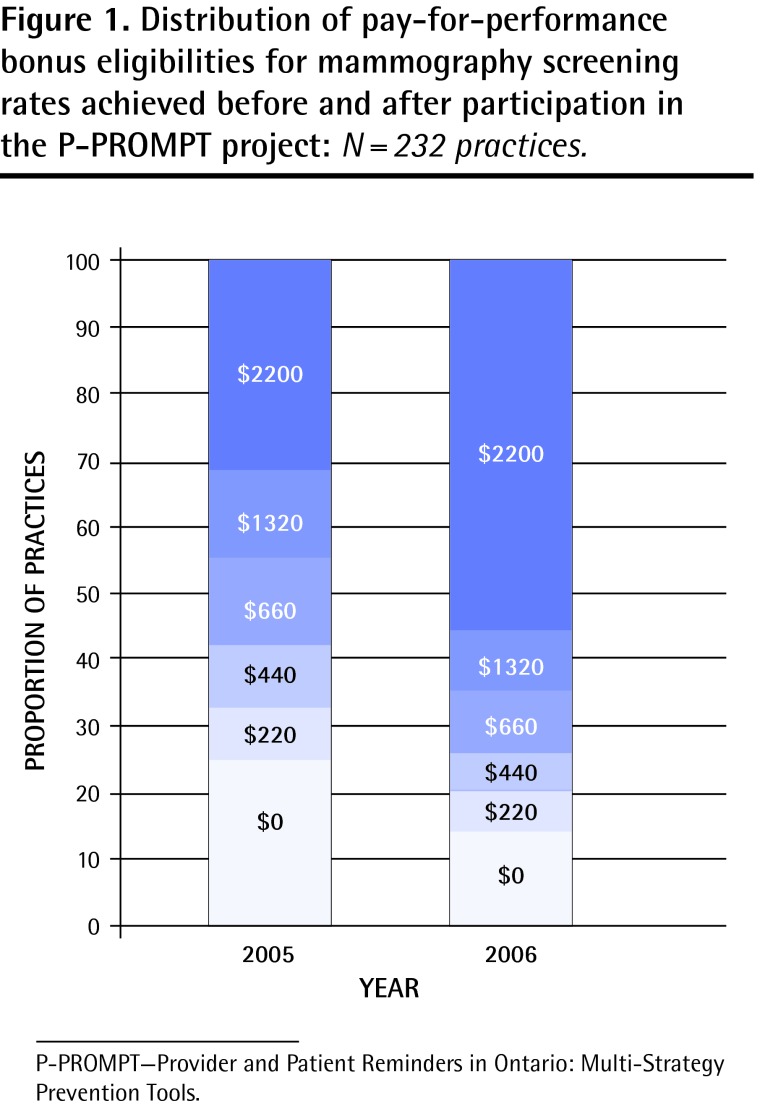

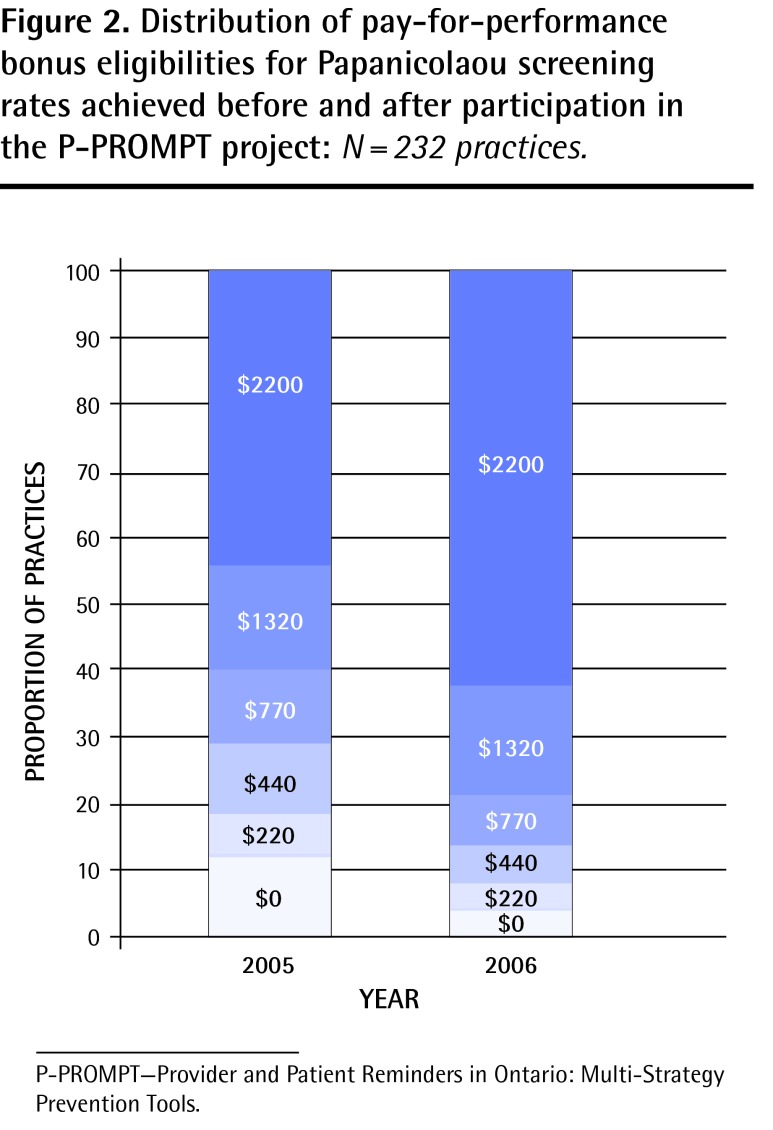

The proportion of practices that achieved the highest performance level (≥ 75% and ≥ 80%) increased from 44.8% to 62.9% for mammograms (McNemar test χ2 = 30.0, P < .001) and from 31.5% to 55.6% for Pap testing (McNemar test χ2 = 52.2, P < .001) (Figures 1 and 2, respectively). In terms of cervical cancer screening rates, the proportion of practices in the top tier (≥ 80%) increased from 31.5% to 55.6%. Conversely, the proportion of practices in the lowest tier (< 60%) decreased from 25% to 14%. The proportion of practices in the top tier for mammography screening (≥ 75%) increased from 44.8% to 62.9%, and those in the lowest tier (< 55%) decreased from 12% to 5%.

Figure 1.

Distribution of pay-for-performance bonus eligibilities for mammography screening rates achieved before and after participation in the P-PROMPT project: N = 232 practices.

P-PROMPT—Provider and Patient Reminders in Ontario: Multi-Strategy Prevention Tools.

Figure 2.

Distribution of pay-for-performance bonus eligibilities for Papanicolaou screening rates achieved before and after participation in the P-PROMPT project: N = 232 practices.

P-PROMPT—Provider and Patient Reminders in Ontario: Multi-Strategy Prevention Tools.

DISCUSSION

We found that the P-PROMPT project, which combined patient and provider reminders, NPs, and pay-for-performance incentives, resulted in significant increases in the uptake of Pap tests and mammograms among eligible primary care patients over a 1-year period in southwestern Ontario. These increases were significant both from the statistical and from the population health perspective.

The P-PROMPT project successfully demonstrated that a multi-strategy reminder and recall system for targeted preventive care services based on data integration and feedback can be successfully implemented on a large scale in family practices in Ontario. The NP-augmented strategy achieved comparable rate increases to the automated strategy alone in the delivery of both preventive tests. While this is both unexpected and somewhat disappointing, it is probably owing to the fact that NP allocation was based on logistic rather than need-based considerations. The end result was that NPs were placed in practices with considerably higher baseline rates for both services, thus introducing a potential for a “ceiling” effect.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to our findings. First, because the P-PROMPT project involved a combined intervention using both bonus incentives and reminder letters, it is not possible to separate the effects of the bonus incentives from those of the reminder letters on increases in mammogram and Pap test rates. While research examining the effectiveness of provider financial incentives to improve the delivery of preventive care services is accumulating, the evidence remains largely inconclusive.19 A systematic review of 8 randomized trials examining the effect of financial incentives for health care providers on preventive care services (including immunizations and cancer screening) found that only 1 intervention led to substantially greater preventive care delivery—physician performance bonuses for providing influenza immunizations.20 A 2008 review examined current peer-reviewed evaluations of purchaser pay-for-performance initiatives in “real world” settings and found improvements in certain quality measures.21 However, because financial incentives were usually combined with other quality improvement measures, the specific effect of financial incentives on quality improvement was not clear.

Second, our study was designed as a before-and-after investigation without a concurrent control group. Some of the improvements might be due to the overall temporal changes in the provision of preventive services in Ontario, and some might be associated with the introduction of financial incentives. Our study design and the existing data do not allow us to disentangle these effects. However, a recent Ontario population-based study that used health administrative data to compare performance of different primary care models during a comparable time frame showed that the only area in which primary care network and family health team practices substantially improved their performance compared with family health groups was in cervical, breast, and colorectal cancer screening.22 It is worth noting that almost half of the primary care network and family health network groups (232 of 474) examined in that study participated in the P-PROMPT project and that practices under both types of models were eligible for identical financial incentives except for additional reminder fee payments ($6.86) available within the primary health network or family health network model to contact patients for cervical, breast, and colorectal cancer screening.

Third, the reported changes in the delivery of Pap tests and mammograms were based on available administrative data. The usual cautions associated with incompleteness or tardiness of family practice billing data apply, especially billings outside of the fee-for-service model. Finally, the baseline preventive care delivery rates for the participating physicians, and especially for those applying the NP-augmented strategy, were higher than the Ontario average rates, suggesting that physicians electing to participate in the study might have a higher interest in the delivery of preventive services to start with. It is unclear how their motivation might have affected study outcomes.

Despite these limitations, the present study illustrates that financial incentives in combination with an effective support system can lead to improved results. Furthermore, our recent publications that examined the attitudes of physicians participating in this project have shown a considerable endorsement for the P-PROMPT approach from participating physicians.18,23 This endorsement was further supported by patients who indicated that reminder letters substantially motivated them to receive the preventive care, and that they would want to continue receiving the letters in the future.24–26 Future research should employ a more rigorous evaluation framework, including identification of the “active” ingredients within the P-PROMPT program.

Conclusion

This demonstration project illustrated that financial incentives in combination with an effective support system can lead to improved preventive screening results. Based on the outcomes from this field-tested model of enhancing the uptake of preventive health care services, as well as other positive findings reported elsewhere in the literature, a provincewide application to test the applicability and effectiveness of this model for delivering other health services, including chronic disease management, might be warranted.

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (Primary Health Care Transition Fund G03-02757). Opinions are those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Preventive care service delivery rates in primary care settings in Canada continue to be lower than recommended.

This study describes the effects of the Provider and Patient Reminders in Ontario: Multi-Strategy Prevention Tools reminder and recall system for preventive care services in Ontario primary care practices using a before-and-after design.

This study found that the use of patient and provider reminders, in conjunction with pay-for-performance incentives, resulted in significant increases (P < .001) in the uptake of Papanicolaou tests and mammograms over a 1-year period. The study contributes to our knowledge base about the effectiveness of financial provider incentives and provider and patient reminders for increasing the delivery rates of preventive care services.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Au Canada, le taux de prestation des services de santé préventifs dans les établissements de soins primaires demeure inférieur au taux recommandé.

Cette étude décrit les effets du projet Provider and Patient Reminder in Ontario : Multi Strategy Prevention Tools (P-PROMPT), un système de mémos et de rappels pour les soins de santé préventifs dans les cliniques de soins primaires de l’Ontario, et ce, en comparant la situation avant et après l’implantation du système.

L’étude a montré que l’utilisation de rappels à l’intention des patientes et des soignants, associée à des mesures financières incitatives basées sur le rendement a causé une augmentation significative (P < ,001) des Pap tests et des mammographies effectués sur une période d’un an. Cette étude contribue ainsi à rappeler que des mesures financières incitatives et des rappels à l’intention des soignants et des patientes sont des mesures efficaces pour augmenter le taux de prestation des services de santé préventifs.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the concept and design of the study; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

After the end date of this study, Dr Sebaldt agreed to continue providing the P-PROMPT services to Ontario physicians for an annual subscription fee.

References

- 1.Cancer Care Ontario [website] Breast cancer screening. Toronto, ON: Cancer Care Ontario; 2012. Available from: www.cancercare.on.ca/pcs/screening/breastscreening/. Accessed 2013 May 1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang L, Jason XN, Upshur RE. Determining use of preventive health care in Ontario. Comparison of rates of 3 maneuvers in administrative and survey data. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:178–9. e1–5. Available from: www.cfp.ca/content/55/2/178.full.pdf+html. Accessed 2013 May 1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadian Partnership Against Cancer . The 2011 cancer system performance report. Toronto, ON: Canadian Partnership Against Cancer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baron RC, Melillo S, Rimer BK, Coates RJ, Kerner J, Habarta N, et al. Intervention to increase recommendation and delivery of screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers by healthcare providers: a systematic review of provider reminders. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(1):110–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dexheimer JW, Talbot TR, Sanders DL, Rosenbloom ST, Aronsky D. Prompting clinicians about preventive care measures: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15(3):311–20. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2555. Epub 2008 Feb 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobson Vann JC, Szilagyi P. Patient reminder and patient recall systems to improve immunization rates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD003941. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003941.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Austin SM, Balas EA, Mitchell JA, Ewigman BG. Effect of physician reminders on preventive care: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1994:121–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagner TH. The effectiveness of mailed patient reminders on mammography screening: a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(1):64–70. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(97)00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laara E, Day NE, Hakama M. Trends in mortality from cervical cancer in the Nordic countries: association with organised screening programmes. Lancet. 1987;1(8544):1247–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92695-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forbes C, Jepson R, Martin-Hirsch P. Interventions targeted at women to encourage the uptake of cervical screening. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(3):CD002834. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonfill X, Marzo M, Pladevall M, Marti J, Emparanza JI. Strategies for increasing the participation of women in community breast cancer screening. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(1):CD002943. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trinite T, Loveland-Cherry C, Marion L. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: an evidence-based prevention resource for nurse practitioners. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2009;21(6):301–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2009.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown SA, Grimes DE. A meta-analysis of nurse practitioners and nurse midwives in primary care. Nurs Res. 1995;44(6):332–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Health Canada [website] Primary Healthcare Transition Fund. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada; 2007. Available from: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/prim/phctf-fassp/index-eng.php. Accessed 2012 Jun 12. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care . Guide to physician compensation. Ottawa, ON: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2009. Available from: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/fht/docs/fht_compensation.pdf. Accessed 2013 May 1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care [website] Edmonton, AB: Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care; 2013. Available from: www.canadiantaskforce.ca. Accessed 2010 Jun 21. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson KK, Sebaldt RJ, Lohfeld L, Goeree R, Donald FC, Burgess K, et al. Practice and physician characteristics associated with influenza vaccination delivery rates following a patient reminder letter intervention. J Prim Prev. 2008;29(1):93–7. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0120-x. Epub 2008 Jan 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson KK, Sebaldt RJ, Lohfeld L, Burgess K, Donald FC, Kaczorowski J. Views of family physicians in southwestern Ontario on preventive care services and performance incentives. Fam Pract. 2006;23(4):469–71. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cml013. Epub 2006 Apr 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flodgren G, Eccles MP, Shepperd S, Scott A, Parmelli E, Beyer FR. An overview of reviews evaluating the effectiveness of financial incentives in changing healthcare professional behaviours and patient outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD009255. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Town R, Kane R, Johnson P, Butler M. Economic incentives and physicians’ delivery of preventive care: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(2):234–40. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christianson JB, Leatherman S, Sutherland K. Lessons from evaluations of purchaser pay-for-performance programs: a review of the evidence. Med Care Res Rev. 2008;65(6 Suppl):5S–35S. doi: 10.1177/1077558708324236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaakkimainen RL, Barnsley J, Klein-Geltink J, Kopp A, Glazier RH. Did changing primary care delivery models change performance? A population based study using health administrative data. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-44.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaczorowski J, Goldberg O, Mai V. Pay-for-performance incentives for preventive care. Views of family physicians before and after participation in a reminder and recall project (P-PROMPT) Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:690–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaczorowski J, Karwalajtys T, Lohfeld L, Laryea S, Anderson K, Roder S, et al. Women’s views on reminder letters for screening mammography. Mixed methods study of women from 23 family health networks. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:622–3. e1–4. Available from: www.cfp.ca/content/55/6/622.full.pdf+html. Accessed 2013 May 2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson KK, Sebaldt RJ, Lohfeld L, Karwalajtys T, Ismaila AS, Goeree R, et al. Patient views on reminder letters for influenza vaccinations in an older primary care patient population: a mixed methods study. Can J Public Health. 2008;99(2):133–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03405461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karwalajtys T, Kaczorowski J, Lohfeld L, Laryea S, Anderson K, Roder S, et al. Acceptability of reminder letters for Papanicolaou tests: a survey of women from 23 family health networks in Ontario. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007;29(10):829–34. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)32640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]