Abstract

Objective

To characterize the demographic characteristics, practice profile, and current work life of general practitioners in oncology (GPOs) for the first time.

Design

National Web survey performed in March 2011.

Setting

Canada.

Participants

Members of the national GPO organization. Respondents were asked to forward the survey to non-member colleagues.

Main outcome measures

Profile of work as GPOs and in other medical roles, training received, demographic characteristics, and professional satisfaction.

Results

The response rate was 73.3% for members of the Canadian Association of General Practitioners in Oncology; overall, 120 surveys were completed. Respondents worked in similar proportions in small and larger communities. About 60% of them had participated in formal training programs. Most respondents worked part-time as GPOs and also worked in other medical roles, particularly palliative care, primary care practice, teaching, and hospital work. More GPOs from cities with populations of greater than 100 000 worked solely as GPOs than those from smaller communities (P = .0057). General practitioners in oncology played a variety of roles in the cancer care system, particularly in systemic therapy, palliative care, inpatient care, and teaching. As a group, more than half of respondents were involved in the care of each of the 11 common cancer types. Overall, 87.8% of respondents worked in outpatient care, 59.1% provided inpatient care, and 33.0% provided on-call services; 92.8% were satisfied with their work as GPOs.

Conclusion

General practitioners in oncology are involved in all cancer care settings and usually combine this work with other roles, particularly with palliative care in rural Canada. Training is inconsistent but initiatives are under way to address this. Job satisfaction is better than that of Canadian FPs in general. As generalists, FPs bring a valuable skill set to their work as GPOs in the cancer care system.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer les caractéristiques démographiques, le profil de pratique et la vie professionnelle actuelle des médecins omnipraticiens en oncologie (MOO) pour la première fois.

Type d ‘étude

Enquête nationale effectuée en mars 2011.

Contexte

Le Canada.

Participants

Des membres de l’Association canadienne des MOO. On a demandé aux répondants de transmettre le questionnaire aux collègues non membres.

Principaux paramètres à l’étude

Description du travail comme MOO et dans d’autres fonctions médicales, formation reçue, caractéristiques démographiques et satisfaction professionnelle.

Résultats

Le taux de réponse était de 73,3 % parmi les membres de l’Association canadienne des médecins omnipraticiens en oncologie; un total de 120 questionnaires ont été complétés. Les lieux de travail des répondants se répartissaient également entre des petites et des grandes collectivités. Environ 60 % des MOO avaient participé à un programme officiel de formation. La plupart faisaient de l’oncologie à temps partiel et assumaient aussi d’autres rôles comme médecins, notamment dans les soins palliatifs, les soins primaires, l’enseignement et le travail hospitalier. Les MOO des villes de plus de 100 000 habitants étaient plus nombreux que ceux des collectivités plus petites à travailler uniquement en oncologie. Les omnipraticiens en oncologie assumaient diverses fonctions dans le traitement du cancer, en particulier pour la thérapie systémique, les soins palliatifs, les soins hospitaliers et l’enseignement. En tant que groupe, plus de la moitié des répondants contribuaient au traitement de 11 types fréquents de cancer. Dans l’ensemble, 87,8 % des répondants œuvraient dans les soins extrahospitaliers, 59,1 % dans les soins hospitaliers et 33,0 % fournissaient des services sur appel; 92,8 % se disaient satisfaits de leur travail comme MOO.

Conclusion

Les omnipraticiens en oncologie travaillent dans tous les types de soins aux cancéreux et ils combinent ce travail avec d’autres fonctions, notamment pour les soins palliatifs dans les régions rurales du Canada. Ils n’ont pas toujours de formation, mais on s’occupe présentement de corriger cette lacune. La satisfaction professionnelle est généralement supérieure à celle des MF canadiens en général. En tant que généralistes, les MF maîtrisent un ensemble d’habiletés, ce qui facilite leur travail comme MOO dans le système des soins aux cancéreux.

An important trend in the Canadian physician work force is the growing number of FPs narrowing their scope of practice and focusing on clinical areas of particular interest. The College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC) defines FPs with focused practices as those with commitments to 1 or more specific clinical areas as substantial part-time or full-time components of their practices.1 According to the 2010 National Physician Survey (NPS) 30.5% of FPs indicated they have a specific area of focus in their practices,2 with the most common areas being maternal care, emergency medicine, mental health and counseling, and hospital care. Concerns have been expressed about the tensions between this trend and the need to encourage and sustain traditional comprehensive family practice.3–5 In 2011, the CFPC created a new Section for Family Physicians with Special Interests or Focused Practices to “offer increased support for family physicians who incorporate special interests and skills as part of their traditional broad-scope family practices, as well as for those who have focused their practices in specific areas of care.”4 A special focus in cancer was not included as a response option in the 2010 NPS; however, 5.2% of FPs, which corresponds to about 1700 FPs nationally, indicated that more than 10% of patients in their practices had cancer. It is not clear what proportion of these FPs are employed in cancer care or palliative care programs or are caring for a large proportion of cancer patients in their primary care practices, or whether they are doing both.

Family physicians have been working in formal outpatient and inpatient cancer settings for several decades in Canada. In Manitoba, FPs began supervising chemotherapy in small towns and cities in 1978 in an outreach program,6 while cancer centres in Toronto, Ont, and Ottawa, Ont, have employed FPs (originally called clinical associates) since the 1980s. The role of FPs in supervising cancer therapy in a shared-care relationship with oncology specialists is established in much of Canada. The Canadian Association of General Practitioners in Oncology (CAGPO) was formed in 2003 to foster a common identity and meet the continuing education needs of these physicians, now commonly called general practitioners in oncology (GPOs) or family physicians in oncology. Membership is drawn from all Canadian provinces, but primarily from Ontario (39%) and British Columbia (30%). This paper provides the results of a national survey of GPOs performed in 2011, and describes for the first time the demographic characteristics, practice profile, and current work life of this physician group.

METHODS

A Web-based survey was sent to members and former members of CAGPO in March 2011. Members received a notifying e-mail followed by an e-mail containing a URL directing them to the survey site, and then a reminder e-mail 1 week later. They were also asked to forward the e-mail invitation to other FPs working in the cancer care system who might not be members of CAGPO, but members were not asked to report such activity to the survey team. A draw for a tablet computer was offered as an incentive. The survey was developed by a CAGPO task group and was adapted from a 2008 survey of Canadian hospitalists.7 It was hosted by SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com), a commercial Web-based survey site, and had 72 questions in a variety of response formats to assess demographic characteristics, training, the profile of their work as GPOs and in other medical roles, remuneration, professional satisfaction, and other areas. Comments could be added as free text on several questions. The survey was pilot-tested by 6 Canadian GPOs for face validity and clarity, and was supported by a medical librarian with expertise in online survey methods. Results were analyzed using simple descriptive statistics. Responses to most quantitative questions were collected in ordinal categories and were reported as medians. Research ethics approval was not sought, given the very minimal risk inherent in Web-based surveys of physicians.

RESULTS

Survey invitations were sent to 146 members of CAGPO and 120 responses were received—97 of these responses were from members of CAGPO. Eighteen respondents were non-members and 5 declined to specify. This represents a response rate of 73.3% among members. Characteristics of respondents are presented in Table 1. Most respondents were from Ontario or British Columbia and worked in similar proportions in communities with small, medium, and large populations. Of the respondents, 60% reported more than 5 years of experience working as a GPO. Three-quarters of respondents were CFPC Certificants, members, or both. General practitioners in oncology in larger cities (population > 100 000) were more likely than their rural counterparts to be older than 50 years of age ( , P = .023).

Table 1.

Characteristics of survey respondents (N = 120) compared with FP respondents to the 2010 NPS:Sixty (50.0%) survey participants were aged ≤ 50 years and 60 (50.0%) were aged > 50 years. The mean age of the NPS respondents was 49.7 years.

| CHARACTERISTIC | SURVEY RESPONDENTS, N (%) | FP RESPONDENTS TO THE 2010 NPS (N = 6602), % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| • Male | 46 (38.3) | 59.6 |

| • Female | 74 (61.7) | 40.0 |

| Province | ||

| • Ontario | 44 (36.7) | 34.2 |

| • British Columbia | 35 (29.2) | 15.0 |

| • Manitoba | 12 (10.0) | 3.6 |

| • Quebec | 7 (5.8) | 24.1 |

| • New Brunswick | 7 (5.8) | 2.9 |

| • Nova Scotia | 5 (4.2) | 3.5 |

| • Newfoundland and Labrador | 3 (2.5) | 2.0 |

| • Saskatchewan | 3 (2.5) | 3.2 |

| • Alberta | 3 (2.5) | 1.2 |

| • Prince Edward Island | 1 (0.8) | 0.5 |

| Community size | ||

| • < 10 000 | 14 (11.7) | 13.6* |

| • 10 000–100 000 | 30 (25.0) | 18.1† |

| • 100 001–500 000 | 37 (30.8) | 62.7‡ |

| • > 500 000 | 39 (32.5) | NA |

| Experience as GPO, y | ||

| • < 2 | 11 (9.2) | NA |

| • 2–5 | 36 (30.0) | NA |

| • 6–10 | 34 (28.3) | NA |

| • 11–19 | 26 (21.7) | NA |

| • ≥ 20 | 12 (10.0) | NA |

| • No answer | 1 (0.8) | NA |

| Status with CFPC | ||

| • Certificant | 21 (17.5) | NA |

| • Member | 21 (17.5) | NA |

| • Both Certificant and member | 47 (39.2) | NA |

| • Not connected | 30 (25.0) | NA |

| • No answer | 1 (0.8) | NA |

CFPC—College of Family Physicians of Canada, GPO—general practitioner in oncology, NA—not available, NPS—National Physician Survey.

Value for the NPS “rural or remote” category.

Value for the NPS “small town” category.

Value for the NPS “urban or suburban” category.

Training and professional development

About 60% of respondents indicated they had participated in organized training programs, but this varied by province. Three-quarters of Ontario respondents did not receive any formal training, while 68.6% of respondents in British Columbia had received such training, mostly in the form of supervised clinical experience.

Describing the role

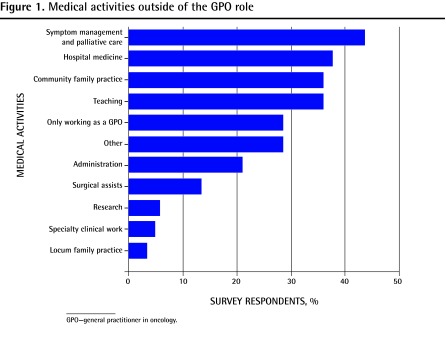

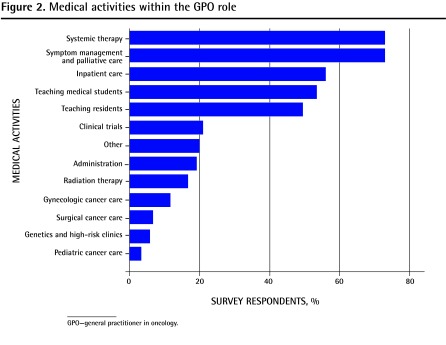

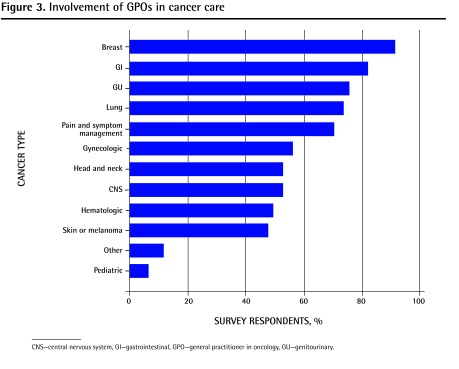

Less than a third of respondents (28.6%) worked only as GPOs. Most respondents indicated they also worked in other medical roles, most commonly palliative care, hospital work, community family practice, and teaching (Figure 1). Respondents in communities of less than 100 000 people were less likely than those from larger cities to be working only as GPOs (13.6% vs 37.3%, , P = .0057) and more likely also to be involved in palliative care (72.7% vs 26.7%, , P < .001). The median overall full-time equivalent (FTE) for all physician work roles was 1.0, with a median FTE of 0.6 for work as a GPO. General practitioners in oncology in communities of less than 100 000 people had a median FTE of 0.4, and GPOs in larger cities had a median FTE of 0.8. Within the cancer care system, respondents played a variety of roles (Figure 2) and were most active in systemic therapy and symptom management–palliative care roles (73.1% for each), with substantial proportions engaged in inpatient care (56.3%) and the teaching of medical students and residents (53.8% and 49.6%, respectively). General practitioners in oncology were most active in the care of patients with breast and gastrointestinal cancer, but more than half of all respondents were involved in other common cancer types. Only 6.7% of respondents were active in treatment of pediatric cancer (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Medical activities outside of the GPO role

GPO—general practitioner in oncology.

Figure 2.

Medical activities within the GPO role

GPO—general practitioner in oncology.

Figure 3.

Involvement of GPOs in cancer care

CNS—central nervous system, GI—gastrointestinal, GPO—general practitioner in oncology, GU—genitourinary.

Settings of care

In characterizing their work as GPOs, 101 of 115 respondents (87.8%) indicated that they worked in the outpatient setting, 68 of 115 respondents (59.1%) said they provided inpatient care, and 37 of 112 respondents (33.0%) provided on-call services outside of regular hours, usually from home. In the outpatient setting, respondents worked a median of 4 half-day clinics per week, where they saw a median of 7 to 8 patients per clinic. In inpatient care, respondents worked a median of 4 half days a week on the wards, caring for a median of 5 to 6 patients. Respondents working in cities of more than 100 000 most commonly reported working 0.5 FTEs or more doing inpatient care. General practitioners in oncology in smaller communities described functioning as consultants to their colleagues for inpatients with cancer, acting as admitting physicians only for their own family practice patients or for cancer patients without admitting FPs. Respondents described their typical inpatients as being admitted for toxicities from treatment, for palliative symptom control, for oncologic emergencies, and as new patients in the process of formal diagnosis.

Remuneration

About 40% of responders were paid on a sessional basis with their hospital or health authority, while 32.2% were on salary, 21.2% were paid on a fee-for-service basis, 5.1% were paid by a university, and 16.9% described a blend of the above.

Job satisfaction

Most respondents (83.9%) worked in primary care practices before starting GPO work, while 42.0% did hospital medicine and 25.9% worked in palliative care. Only 7.1% of respondents had only ever worked as GPOs. Respondents reported high job satisfaction, with 92.8% describing themselves as satisfied or extremely satisfied with their work as GPOs. Compared with their previous clinical work, 64.3% indicated they had higher professional satisfaction now as GPOs. However, concerns were expressed about inequality of remuneration compared with community FPs and GPs, and the feeling of marginalization as FPs working in a medical staff comprising mainly oncologists. Respondents agreed that their relationships with community FPs and local oncologists (84.9% and 92.0%, respectively) were cooperative and respectful, but only 64.3% of respondents described their relationships with their hospital administration in this way. About two-thirds (66.1%) said that they expected to be working as GPOs in 5 years’ time, with moves to community-based family medicine (38.4%) or retirement (23.2%) as the most common anticipated career changes.

Relationship with the CFPC

About three-quarters of respondents were CFPC Certificants, members, or both, and 82.4% of respondents supported CAGPO pursuing closer ties with the CFPC Section of Family Physicians with Special Interests or Focused Practices. More than 80% of respondents supported the development of a certification process for GPOs, particularly if there were financial incentives for achieving such certification.

DISCUSSION

Shortages of medical oncologists have been identified as a concern in oncology work force studies in Ontario,8 the United States,9 and Australia.10 An expanded role for nononcologist providers in the cancer care system has been proposed as a way of mitigating this situation. The literature on “alternate providers” within the cancer care system focuses on the role of nurse practitioners11 and, particularly in the United States, of physician assistants, usually working in proximity to oncologists in urban cancer centres.12,13 In one US study, these nonphysician practitioners were present in 58.8% of the 226 cancer practices surveyed, where they played a variety of clinical roles with excellent patient and provider satisfaction and high clinic productivity.14 The role of GPOs was endorsed in a 2000 Ontario cancer task force report8 but has otherwise received little attention in the published literature.

This survey of Canadian GPOs paints the picture of a professional group active in communities of all sizes, working in a variety of roles and practice settings within the cancer care system and with a range of cancer patients. These physicians usually combine part-time work as GPOs with other medical activities such as hospital medicine, palliative care, and family practice. The clinical role focuses on the supervision of systemic therapy (chemotherapy) and palliative care and symptom management; however, it is difficult to clarify from the responses the extent to which palliative care is offered as a distinct clinical service or whether it is integrated with the supervision of cancer treatment. Although the older term clinical associate emphasizes the patient care role of these physicians, their involvement in teaching, clinical research, and administrative work within the cancer care system is substantial.

Compared with FPs in the 2010 NPS, GPOs are of similar age and are located in similar proportions in communities of different sizes, but they are more likely to be women and more likely to be paid on a sessional or service contract (40.7 vs 6.8%) or salaried (32.2 vs 7.6%) basis. They also report higher job satisfaction than other FPs: 93% of GPOs were satisfied or extremely satisfied, compared with 75.6% of FPs in the NPS. Despite a sense of professional isolation and marginalization,15 almost two-thirds of GPOs were happier than in their previous work, which was most commonly family practice.

The profile of rural GPOs is somewhat different than that of their urban counterparts. A smaller portion of their work as physicians was identified as GPO work, and they were more likely to be working in other roles in their communities, particularly in providing palliative care services. In Manitoba, about 25% of all chemotherapy is provided in rural communities under the supervision of hospital-based teams, which include GPOs, nurses, and pharmacists.16 Despite concerns expressed about FPs leaving comprehensive family practices, the provision of specialized services such as cancer treatment in rural Canada appears to depend on the presence of FPs with focused practices.

Given the unique skills and knowledge needed in oncology care, it is concerning that the formal training of GPOs is inconsistent across the country. This ad hoc approach to training is echoed in a US study in which 60% of cancer practices reported only informal, on-the-job training for physician assistants and nurse practitioners working in their centres.14 Concern has been expressed in Canada about the lack of certification of competence for FPs in some types of focused practices.17 In response to a similar concern, the National Health Service in the United Kingdom has produced guidelines for the national accreditation of GPs with special interests, a move being contemplated by the CFPC.17 Most respondents in this survey support the move to a certification process for GPOs, and programs are now developing across the country. The BC Cancer Agency hosts the most comprehensive GPO training program in Canada, which combines 2 weeks of didactic learning with 6 weeks of supervised oncology practice in regional cancer centres.18 In addition, 3 Canadian departments of family medicine are now offering so-called third-year or enhanced skills programs in oncology for family medicine residents or practising physicians.19–21

Limitations

The interpretation of this survey is limited by our sampling approach. The number of FPs working nationally as GPOs is unknown. Respondents were limited mainly to CAGPO members, largely from Ontario and British Columbia, who are more likely to identify strongly with their work as GPOs and might not be representative of all such physicians.

Conclusion

Family physicians bring a valuable skill set to their work as GPOs in the cancer care system. Their strength as generalists22 who combine advanced clinical skills with an integrative, patient-centred approach offers a unique perspective and flexibility within the multidisciplinary cancer care team. They also serve as natural bridges between the community primary care practice and the specialist cancer care system at a time when the emphasis on closer collaboration with primary care is increasing within the formal cancer care system.23,24 The role of FPs with focused practices is particularly critical in rural Canada if cancer and other kinds of specialized care are to be provided closer to home. The portrait of GPOs painted in this survey enhances the understanding of this emerging focused practice within family medicine and provides an empiric basis for work force planning in the cancer care system in Canada.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Almost a third of Canadian FPs have focused practices, in which specific clinical areas are important components of their work. Because of geography and oncologist shortages, general practitioners in oncology (GPOs) are important but poorly characterized “alternate providers” in the cancer care system. This is the first profile of GPOs in Canada.

General practitioners in oncology are active in communities of all sizes, working in a variety of roles and practice settings within the cancer care system and with a range of cancer patients. Most of them combine part-time work as GPOs with other medical activities such as palliative care, primary care, teaching, and hospital work. They have higher job satisfaction than the national benchmark.

Formal cancer training for GPOs in Canada is variable. Most respondents in this survey support the move to a certification process for GPOs, and programs are now developing across the country.

POINTS DE REPÉRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Près d’un tiers des MF canadiens ont une pratique ciblée, dans laquelle certains domaines cliniques spécifiques occupent une place importante. Les contraintes géographiques et le manque d’oncologistes font en sorte que les omnipraticiens qui font de l’oncologie (MOO) sont des substituts précieux, mais mal caractérisés dans le système de soins aux cancéreux. Ceci est la première description du travail des MOO au Canada.

Les omnipraticiens en oncologie pratiquent dans des collectivités de toutes tailles dans des fonctions et des contextes de pratique variés à l’intérieur du système de soins liés au cancer, et ce, pour plusieurs types de cancer. La plupart d’entre eux associent un travail à temps partiel comme MOO à d’autres activités médicales telles que les soins palliatifs, les soins primaires, l’enseignement et le travail hospitalier. Leur niveau de satisfaction est supérieur à la référence nationale.

Au Canada, il n’y a pas toujours de formation officielle pour les MOO. La plupart des répondants à cette enquête sont en faveur d’un processus de certification pour les MOO; des programmes sont d’ailleurs en voie d’élaboration un peu partout au pays.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Contributors

Drs Sisler, DeCarolis, and Robinson were involved in the design, execution, data analysis, and preparation and review of the manuscript. Dr Sivananthan was involved in data analysis and preparation and review of the manuscript.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.College of Family Physicians of Canada [website] Section of Family Physicians with Special Interests or Focused Practices. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2012. Available from: www.cfpc.ca/SIFP_Resources/. Accessed 2013 May 14. [Google Scholar]

- 2.College of Family Physicians of Canada, Canadian Medical Association, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada . 2010 National Physician Survey. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2010. Available from: www.nationalphysiciansurvey.ca. Accessed 2013 May 14. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaulieu MD, Rioux M, Rocher G, Samson L, Boucher L. Family practice: professional identity in transition. A case study of family medicine in Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(7):1153–63. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.019. Epub 2008 Jul 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gutkin C. Special interest areas in your practice? Tell us more. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:1096, 1095. (Eng), 1094–5 (Fr) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collier R. The changing face of family medicine. CMAJ. 2011;183(18):E1287–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4036. Epub 2011 Nov 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CancerCare Manitoba [website] Community cancer programs network. Winnipeg, MB: CancerCare Manitoba; 2012. Available from: www.cancercare.mb.ca/home/patients_and_family/treatment_services/treating_patients_in_rural_manitoba/community_cancer_programs_network/. Accessed 2013 May 14. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canadian Society of Hospital Medicine [website] CSHM survey results. Canadian Society of Hospital Medicine; 2011. Available from: http://canadianhospitalist.ca/content/cshm-survey-results. Accessed 2013 May 27. [Google Scholar]

- 8.CancerCare Ontario . The systemic therapy task force report. Toronto, ON: CancerCare Ontario; 2000. Available from: www.cancercare.on.ca/common/pages/UserFile.aspx?fileId=14436. Accessed 2013 May 14. [Google Scholar]

- 9.AAMC Center for Workforce Studies . Forecasting the supply of and demand for oncologists: a report to the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) from the AAMC Center for Workforce Studies. Alexandria, VA: American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2007. Available from: www.asco.org/sites/default/files/oncology_workforce_report_final.pdf. Accessed 2013 May 14. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blinman PL, Grimison P, Barton MB, Crossing S, Walpole ET, Wong N, et al. The shortage of medical oncologists: the Australian Medical Oncologist Workforce study. Med J Aust. 2012;196(1):58–61. doi: 10.5694/mja11.10363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bryant-Lukosius D, Green E, Fitch M, Macartney G, Robb-Blenderman L, McFarlane S, et al. A survey of oncology advanced practice nurses in Ontario: profile and predictors of job satisfaction. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont) 2007;20(2):50–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bajorin DF, Hanley A. The study of collaborative practice arrangements: where do we go from here? J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(27):3599–600. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.3695. Epub 2011 Aug 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erikson C, Salsberg E, Forte G, Bruinooge S, Goldstein M. Future supply and demand for oncologists: challenges to assuring access to oncology services. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3(2):79–86. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0723601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Towle EL, Barr TR, Hanley A, Kosty M, Williams S, Goldstein MA. Results of the ASCO Study of Collaborative Practice Arrangements. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(5):278–82. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blouin L. Defining the role of GPOs: pinch hitters or team players? Oncol Exchange. 2012;11(1):8–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.CancerCare Manitoba . 2007–2008 progress report. Navigating cancer services. Winnipeg, MB: CancerCare Manitoba; 2008. Available from: www.cancercare.mb.ca/resource/File/CCMB_Progress_Report_07-08.pdf. Accessed 2013 May 14. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collier R. Potential pitfalls of “specialized” primary care. CMAJ. 2011;183(18):E1291–2. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4044. Epub 2011 Nov 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.BC Cancer Agency [website] GPO training program. Vancouver, BC: BC Cancer Agency; 2012. Available from: http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/HPI/FPON/Precep/default.htm. Accessed 2013 May 16. [Google Scholar]

- 19.University of Manitoba [website] Enhanced skills—cancer care. Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba; 2012. Available from: http://umanitoba.ca/faculties/medicine/units/family_medicine/postgrad/6678.html. Accessed 2013 May 14. [Google Scholar]

- 20.University of Ottawa [website] Family practice (Fp) oncology. Ottawa, ON: University of Ottawa; 2012. Available from: www.familymedicine.uottawa.ca/eng/pg_PGY3-Opp-FP-Oncology.html. Accessed 2013 May 14. [Google Scholar]

- 21.University of Toronto [website] Breast diseases. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto; 2012. Available from: www.dfcm.utoronto.ca/prospectivelearners/prosres/pgy3/pgy3breastdiseases.htm. Accessed 2013 May 14. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stange KC. The generalist approach. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(3):198–203. doi: 10.1370/afm.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sisler J. Partnership with primary care. Oncol Exchange. 2010;9(3):6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sisler J, McCormack-Speak P. Bridging the gap between primary care and the cancer system. The UPCON Network of CancerCare Manitoba. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:273–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]