Abstract

Aims

Hypertrophic remodelling and systolic dysfunction are common in patients with mitochondrial disease and independent predictors of morbidity and early mortality. Screening strategies for cardiac disease are unclear. We investigated whether myocardial abnormalities could be identified in mitochondrial DNA mutation carriers without clinical cardiac involvement.

Methods and results

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was performed in 22 adult patients with mitochondrial disease due to the m.3243A>G mutation, but no known cardiac involvement, and 22 age- and gender-matched control subjects: (i) Phosphorus-31- magnetic resonance spectroscopy, (ii) cine imaging (iii), cardiac tagging and (iv) late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) imaging. Disease burden was determined using the Newcastle Mitochondrial Disease Adult Scale (NMDAS) and urinary mutation load. Compared with control subjects, patients had an increased left ventricular mass index (LVMI), LV mass to end-diastolic volume (M/V) ratio, wall thicknesses (all P < 0.01), torsion and torsion to endocardial strain ratio (both P < 0.05). Longitudinal shortening was decreased in patients (P < 0.0001) and correlated with an increased LVMI (r = −0.52, P < 0.03), but there were no differences in the diastolic function. Among patients there was no correlation of LVMI or the M/V ratio with diabetic or hypertensive status, but the mutation load and NMDAS correlated with the LVMI (r = 0.71 and r = 0.79, respectively, both P < 0.001). The phosphocreatine/adenosine triphosphate ratio was decreased in patients (P < 0.001) but did not correlate with other parameters. No patients displayed focal LGE.

Conclusion

Concentric remodelling and subendocardial dysfunction occur in patients carrying m.3243A>G mutation without clinical cardiac disease. Patients with higher mutation loads and disease burden may be at increased risk of cardiac involvement.

Keywords: Cardiomyopathy, Magnetic resonance imaging, Magnetic resonance spectroscopy, Cardiac tagging, Mitochondrial disease

Introduction

Mitochondrial diseases are an important group of genetic disorders, primarily affecting tissues with high-energy requirements. The m.3243A>G mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutation in the mt-tRNALeu(UUR) gene is the most common pathogenic mutation present in ∼1 in 300 of the general population and causing disease in ∼1 in 6000 individuals.1 Originally described in an individual with mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS), the m.3243A>G mutation also causes maternally inherited diabetes and deafness (MIDD), myopathy, ophthalmoplegia and cardiomyopathy, as isolated clinical features or part of multisystem disease.

Cardiomyopathy, commonly with a hypertrophic phenotype, occurs in 20–40% of patients carrying the m.3243A>G mutation,2–6 and is an independent predictor of morbidity and early mortality;5,7 many patients die from cardiac arrhythmias or congestive heart failure.4 Echocardiography and 12-lead ECG are recommended screening strategies as early identification of asymptomatic cardiac structural defects (stage B cardiomyopathy) allows the initiation of cardioprotective therapies.8 In other neuromuscular diseases associated with cardiomyopathy such interventions slow cardiac remodelling and reduce symptoms.9 Two-dimensional echocardiography has limited sensitivity to detect small changes in left ventricular (LV) mass, particularly in asymptomatic cases,10 and previous studies used normal reference ranges, rather than comparison with age- and gender-matched healthy controls, further decreasing sensitivity.3,5,6 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may reveal cardiac involvement in multisystem disease when standard evaluation is unremarkable,11 and may provide novel therapeutic targets, where the efficacy of early intervention remains to be determined.12

MRI is the gold standard investigation of cardiac morphology and function. Cardiac tagging enables the detection of early defects in myocardial deformation by analysis of circumferential strain and torsion.13 Torsion describes the twisting motion of the heart due to opposite rotation of base and apex, and maintains homogeneity of strain across the myocardial wall. The torsion to endocardial circumferential strain ratio (TSR), a sensitive marker of altered epicardial–endocardial interactions, is constant among healthy individuals of the same age but increases with normal ageing.13 Elevated torsion and/or TSR have been demonstrated in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) caused by increased haemodynamic loading,14 in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) patients,15 and recently, in HCM mutation carriers without hypertrophy, perhaps providing an early phenotypic marker.16

Phosphorus-31 (31P) magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) permits the evaluation of myocardial bioenergetics by calculation of the phosphocreatine (PCr)/adenosine triphosphate (ATP) ratio.17 PCr/ATP ratio is reduced in systolic dysfunction and in HCM with normal systolic function.18 Impaired cardiac bioenergetics occur in mutation carriers of both HCM17 and mitochondrial disease,19 without echocardiographic evidence of hypertrophy, suggesting a potential role in early detection of disease.

Using these modalities, we sought to characterize the cardiac phenotype in a clinically and genetically well-characterized cohort with reference to age- and gender-matched healthy controls. Based on studies in patients with mitochondrial disease,19 and in HCM mutation carriers without hypertrophy,16,17 our hypotheses were that abnormalities of LV mechanics and bioenergetics would be detectable in patients carrying the m.3243A>G mutation without known cardiac involvement, and that such abnormalities would be related to markers of disease burden. We provide a comprehensive MRI/31P MRS evaluation of cardiac changes in this population, with important implications for future screening and management strategies.

Methods

Subjects

Twenty-two adult patients with mitochondrial disease due to the m.3243A>G mutation, but no known cardiac involvement, were recruited from a mitochondrial disease specialist clinic. The absence of cardiac involvement was determined using screening strategies commonly employed in patients with mitochondrial disease, namely clinical history and examination with a normal ECG, echocardiogram (documenting no significant valvular disease, a maximum LV wall thickness ≤12 mm, an ejection fraction ≥55% and the LV end-diastolic dimension ≤32 mm/m2), and exercise stress ECG (documenting no symptoms or ECG changes suggestive of underlying coronary artery disease); patients were excluded using these criteria (n = 3) and the presence of contra-indications to MRI (n = 1; claustrophobia). All 22 patients were matched with respect to age and gender with healthy controls, with a normal ECG and no history of cardiovascular or metabolic disease, recruited through advertisement. Institutional ethical approval and informed consent were obtained and the study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Clinical assessment

Subjects underwent physical examination by an experienced clinician. Disease burden was assessed using the Newcastle Mitochondrial Disease Adult Scale (NMDAS), a validated scoring system.20 The m.3243A>G mutation load was determined in urinary epithelial cells.21 The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated in all patients using the Modified Diet in Renal Disease equation, prior to administration of gadolinium.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

Using a 3-Tesla Intera Achieva scanner (Philips, Best, NL), subjects underwent (i) 31P MRS, (ii) cine imaging, (ii) cardiac tagging, and (iv) late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) imaging.

Cardiac spectroscopy

Subjects were scanned prone, using a 10-cm diameter 31P surface coil (Pulseteq, UK). A cardiac gated one-dimensional (1-D) chemical shift imaging (CSI) sequence was used with spatial pre-saturation of the skeletal muscle. A 7-cm slice was selected using a ‘spredrex’-type pulse of 2.3 ms duration to eliminate liver contamination.22 Negligible liver contamination was assured by 1-D foot-head oriented CSI experiments in phantoms: <1% of the total phosphorus signal originated from outside the prescribed volume. Sixteen coronal phase-encoding steps yielded spectra from 10-mm slices (TR = heart rate, 192 averages, acquisition time approximately 20 min). The first spectrum arising entirely beyond the chest wall was analysed using the AMARES time domain fit23 to quantify PCr, the γ resonance of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (DPG). The ATP peak area was corrected for blood contamination by 1/6th combined 2,3-DPG peak, and PCr/ATP ratios were corrected for T1 saturation and local flip angle.24

Cine imaging

Subjects were scanned supine using a 6-channel cardiac coil and ECG gating (Philips). The short-axis balanced steady-state free precession images were obtained covering the entire left ventricle [field of view (FOV) 350 × 350 mm2, repetition time/echo time (TR/TE) = 3.7/1.9 ms, turbo factor 17, flip angle (FA) 40°, slice thickness 8 mm, 25 phases, resolution 1.37 mm]; long-axis images were acquired. Endocardial and epicardial borders were traced manually on short-axis slices throughout the cardiac cycle using the ViewForum workstation (Philips).The LV mass, and systolic and diastolic parameters, including the ratio of early to late ventricular filling velocity (E/A ratio) and early filling percentage, were calculated as previously described.24 The ratio of the LV mass to end-diastolic volume (M/V ratio) was calculated as an index of concentric hypertrophy.25 Longitudinal shortening was determined in the four-chamber view as the percentage difference in distance from the mitral valve plane to the apex at end-systole and end-diastole. The myocardial wall thickness was determined at the same level as tagging, and the percentage increase from diastole to systole (radial thickening) was calculated.

Cardiac tagging

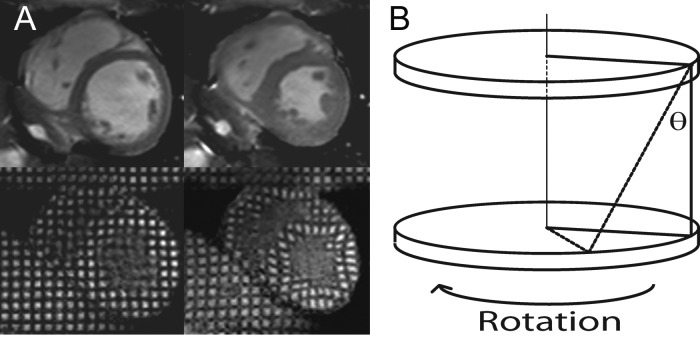

MR signal from the myocardium in diastole was cancelled in a rectangular grid pattern and tags were tracked through the cardiac cycle (Figure 1A).13 A multi-shot turbo-field echo sequence was used (TR/TE/FA/number of averages = 4.9/3.1/10°/1, turbo factor 9, SENSE factor 2, FOV 350 × 350 mm2, voxel size 1.37 mm, tag spacing 7 mm, 12 phases). Two adjacent short-axis slices of 10 mm thickness were acquired at the mid-ventricle with a 2-mm gap. The Cardiac Image Modeling package (Auckland UniServices Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand) was used to align a mesh on the tags between the endocardial and epicardial contours. Peak circumferential strain for both the whole myocardial wall and the endocardial third were calculated. Peak torsion between the two slices was calculated as the circumferential-longitudinal shear angle, defined on the epicardial surface (Figure 1B).13

Figure 1.

Cardiac tagging analysis. (A) Cine imaging (top panels) and tagging (bottom) at end-diastole (left panels) and end-systole (right). A rectangular grid of nulled myocardium applied in the diastole enables tracking of myocardial deformation. (B) Tagging of two parallel short-axis slices allows the calculation of torsion, the longitudinal-circumferential sheer angle (θ) as shown.

LGE imaging

Gadolinium-DTPA of 0.2 mmol/kg (Dotarem, Guerbet, France) was administered intravenously to patients only. LGE images were obtained at 10 min using a breath-held, cardiac-triggered three-dimensional phase-sensitive inversion recovery sequence (multi-shot gradient echo TR/TE = 5/2.4, FA = 15°/5°, acceleration factor 31, parallel imaging factor 2, 1.8-mm resolution zero-filled to 1.3 mm) with the inversion time to null normal myocardium determined from a prior multi-slice 2D Look-Locker experiment (multi-shot EPI with an EPI factor 5, acceleration factor 2, TR/TE = 7.3/2.8, 3-mm resolution). Qualitative analysis for the presence and distribution of LGE in a 17-segment model was performed by two experienced, independent observers, blinded to patient status and MRI/MRS findings as per Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance guidelines26: consensus agreement was planned in the case of initial disagreement between observers.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD for continuous data and as percentages and numbers for categorical data. Continuous data were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and group comparisons were made using two-tailed Student's t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher's exact test and the correlations were executed using Pearson's method. The Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons was used for both group comparisons and correlations. The reliability of MRI measures of myocardial strains and diastolic function were assessed with the Bland–Altman analysis by comparing the values derived from the contours redrawn after 1 month (M.G.D.B.), and by two independent observers (M.G.D.B. and K.G.H.), in four randomly selected patients and four controls. Inter-observer and intra-observer limits of agreement were, respectively, −0.19 ± 0.31° and 0.06 ± 0.51° for torsion, 0.74 ± 1.31 and 1.53 ± 1.08% for endocardial circumferential strain, 0.001 ± 0.11 and 0.08 ± 0.16 for E/A ratio and –0.54 ± 1.58 and 0.68 ± 2.84% for early filling percentage. Using our implementation of cardiac 31P MRS,24 we have previously determined that the reproducibility coefficient of the PCr/ATP ratio was 0.28 or 15% in four control subjects, on two separate occasions. All analysis was performed using SPSS version 17 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). All tests were two-sided and statistical significance was assumed at P < 0.05.

Results

Patient population

Baseline characteristics of 22 patients (19 probands and 3 individual family members, unrelated to each other) are summarized in Table 1. Disease burden was mild or moderate in all patients (11 patients had MIDD, 10 had myopathic phenotype and 1 patient had MELAS). Eleven patients had diabetes mellitus and 5 had treated hypertension. There were no significant differences in the current systolic or diastolic blood pressures. The frequencies of specific clinical features are summarized in Table 2, with individual clinical features and medications in the Supplementary date online, Table S1. The eGFR was >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 in all patients.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Carriers (n = 22) | Controls (n = 22) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42.5 ± 12.2 | 42.8 ± 13.4 | ns |

| Male sex, n (%) | 11 (50) | 11 (50) | ns |

| Height (cm) | 168 ± 11 | 171 ± 11 | ns |

| Weight (kg) | 65.7 ± 16.2 | 77.1 ± 13.4 | ns |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.1 ± 5.1 | 26.6 ± 4.8 | ns |

| Body surface area (m2) | 1.74 ± 0.23 | 1.84 ± 0.19 | ns |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 11 (50) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 5 (23) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Cardiac parameters | |||

| Sinus rhythm, n (%) | 24 (100) | 24 (100) | ns |

| Heart rate (min−1) | 77 ± 13 | 59 ± 9 | <0.0001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 116 ± 13 | 123 ± 11 | ns |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77 ± 8 | 75 ± 9 | ns |

| Selected medications | |||

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 9 (41) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Beta blocker | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Calcium channel blocker | 2 (9) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Statin | 8 (36) | 0 (0) | N/A |

| Insulin | 6 (27) | 0 (0) | N/A |

ns, not significant (P > 0.05); N/A, not applicable; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index.

Table 2.

Frequency of clinical features

| Clinical feature | Number of patients | Percentage of all patients |

|---|---|---|

| Hearing loss | 20 | 91 |

| Exercise intolerance | 17 | 77 |

| Ataxia | 14 | 64 |

| Constipation | 13 | 59 |

| Myopathy | 12 | 55 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 | 50 |

| Migraine | 10 | 45 |

| Depression | 10 | 45 |

| Retinopathy | 8 | 36 |

| Fatigue | 6 | 27 |

| Short stature | 5 | 23 |

| Dysarthria | 4 | 18 |

| Underweight (BMI <18.5) | 4 | 18 |

| Myalgia | 4 | 18 |

| Epilepsy | 2 | 9 |

| Neuropathy | 2 | 9 |

| Hypothyroidism | 2 | 9 |

| Ophthalmoplegia | 2 | 9 |

| Ptosis | 2 | 9 |

| Cataracts | 1 | 5 |

| Encephalopathy | 1 | 5 |

| Dysphagia | 1 | 5 |

| Stroke-like episodes | 1 | 5 |

BMI, body mass index (kg/m2).

Cardiac morphology and global function

Table 3 summarizes the morphological and functional parameters for patient and control groups with all subjects completing the scan protocol (total duration of 77 ± 13 min). The means and ranges of control group parameters are in agreement with a large cohort study using quantitative cardiac MRI.27

Table 3.

Cardiac morphology and function

| Parameter | Patients | Controls | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| End-diastolic volume (mL) | 93 ± 17 | 138 ± 26 | <0.0001 |

| End-diastolic index (mL/m2) | 54 ± 9 | 73 ± 15 | <0.0001 |

| End-systolic volume (mL) | 36 ± 10 | 57 ± 15 | <0.0001 |

| End-systolic index (mL/m2) | 21 ± 6 | 31 ± 8 | <0.001 |

| Stroke volume (mL) | 57 ± 10 | 82 ± 15 | <0.0001 |

| Stroke index (mL/m2) | 33 ± 5 | 45 ± 8 | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac output (l/min) | 4.4 ± 1.0 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | ns |

| Cardiac index (l/min/m2) | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 2.6 ± 0.4 | ns |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 62 ± 7 | 59 ± 6 | ns |

| LV mass (g) | 119 ± 28 | 109 ± 20 | ns |

| Wall thickness in systole (mm) | 13.5 ± 3.1 | 10.9 ± 1.9 | <0.01 |

| Wall thickness in diastole (mm) | 9.8 ± 2.9 | 6.9 ± 1.1 | <0.001 |

| LVMI (LV mass/BSA) (g/m2) | 70 ± 12 | 59 ± 7 | <0.01 |

| M/V ratio (LV mass/end-diastolic volume) (g/mL) | 1.28 ± 0.33 | 0.81 ± 0.14 | <0.0001 |

ns, not significant (P > 0.05); LV, left ventricular; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; BSA, body surface area; M/V, LV mass/end-diastolic volume.

The end-systolic and end-diastolic volumes, both as raw values and when indexed to body surface area (BSA), were significantly decreased in patients compared with controls (Table 3). A proportional decrease in these parameters (33 and 37%, respectively) ensured no significant difference in ejection fraction. Stroke volume and stroke index were significantly decreased in patients: this occurred in association with a significant increase in the heart rate (r = −0.65, P < 0.01) with no significant difference in cardiac output or cardiac index between the groups.

The LV mass was not significantly different between the patient and control groups (Table 3). However, when indexed to BSA, the LV mass index (LVMI) was significantly increased in patients. A significant increase in the M/V ratio (58%) suggested that concentric remodelling had occurred. Consistent with this, the radial wall thicknesses in both diastole and systole were significantly increased in patients. Within the control group, there were significant correlations between the systolic blood pressure and both LV mass (r = 0.57, P < 0.02) and the radial wall thickness in diastole (r = 0.54, P < 0.03). Within the patient group, no significant correlations were shown between systolic or diastolic blood pressure and any markers of LV mass (Supplementary data online, Figure S1). Similarly fasting blood glucose and HbA1C in patients did not correlate significantly with the LV mass, LVMI, radial wall thicknesses or M/V ratio. The exclusion of diabetic or treated hypertensive patients from statistical analyses did not affect significantly increases in LVMI or radial wall thicknesses.

Both the independent observers were in agreement that no patients displayed evidence of focal intramyocardial fibrosis on LGE imaging.

Cardiac tagging and myocardial strains

Longitudinal shortening was significantly decreased (17%) in patients (Table 4) and correlated significantly with an increased LVMI (r = −0.52, P < 0.03). Peak torsion (36%) and TSR (35%) were significantly increased in patients. No significant differences were detected in the rates of systolic and diastolic torsion, after correction for peak torsion, or in the diastolic function represented by the E/A ratio and early filling percentage.

Table 4.

Cardiac tagging and diastolic function

| Parameter | Patients | Controls | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal shortening (%) | 15.1 ± 1.5 | 18.2 ± 2.3 | <0.0001 |

| Radial wall thickening (%) | 65.6 ± 17.0 | 60.1 ± 16.0 | ns |

| Peak torsion (°) | 8.0 ± 2.7 | 5.9 ± 1.4 | <0.03 |

| Systolic torsion rate (°/s) | 37 ± 13 | 24 ± 10 | <0.02 |

| Diastolic torsion rate (°/s) | 23 ± 10 | 17 ± 10 | ns |

| Systolic torsion rate/peak torsion (s−1) | 4.7 ± 1.3 | 4.1 ± 1.8 | ns |

| Diastolic torsion rate/peak torsion (s−1) | 3.0 ± 1.3 | 2.8 ± 1.6 | ns |

| Peak whole wall circumferential strain (%) | 16.7 ± 2.2 | 17.8 ± 2.5 | ns |

| Peak endocardial circumferential strain (%) | 22.6 ± 2.6 | 24.4 ± 2.5 | ns |

| TSR (rad) | 0.62 ± 0.21 | 0.46 ± 0.10 | <0.03 |

| E/A ratio | 1.53 ± 0.55 | 1.75 ± 0.62 | ns |

| Early filling (%) | 72.4 ± 8.9 | 73.2 ± 8.3 | ns |

ns, not significant (P > 0.05); E/A ratio, ratio of early to late ventricular filling velocity; TSR, torsion to endocardial strain ratio.

No significant differences were found in radial thickening or in the circumferential whole wall or endocardial strain (Table 4).

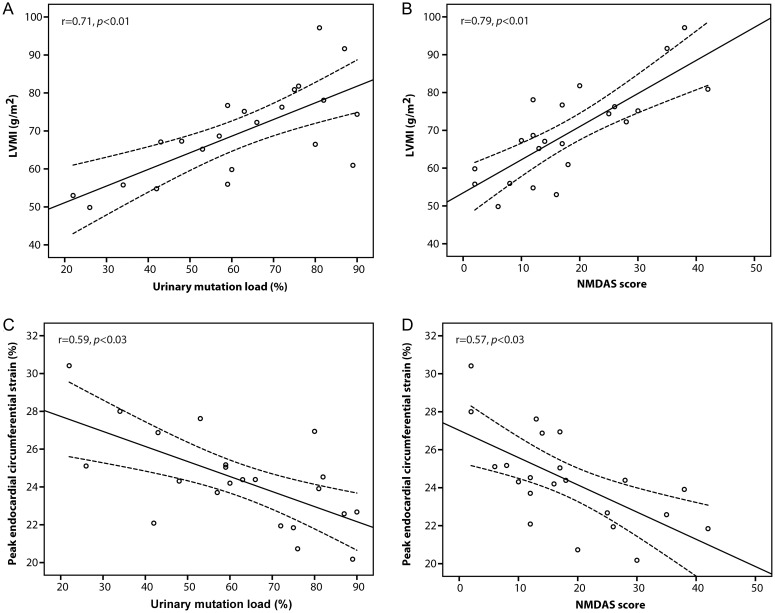

Mutation load and clinical status

There was a significant correlation between the urinary mutation load (mean: 62 ± 20%, range: 22–90%) and disease burden (NMDAS mean score: 18 ± 11, range: 2–42) among patients (r = 0.59, P < 0.02). Both these clinical markers displayed significant correlations with the LVMI (respectively, r = 0.71 and r = 0.79, both P < 0.001), and peak endocardial circumferential strain (r = −0.59 and r = −0.57, both P < 0.03, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

LVMI and clinical markers. LVMI correlated positively with both (A) urinary mutation load and (B) NMDAS score, while peak endocardial circumferential strain correlated negatively with (C) urinary mutation load and (D) NMDAS score. LVMI, left ventricular mass index; NMDAS, Newcastle Mitochondrial Disease Adult Scale.

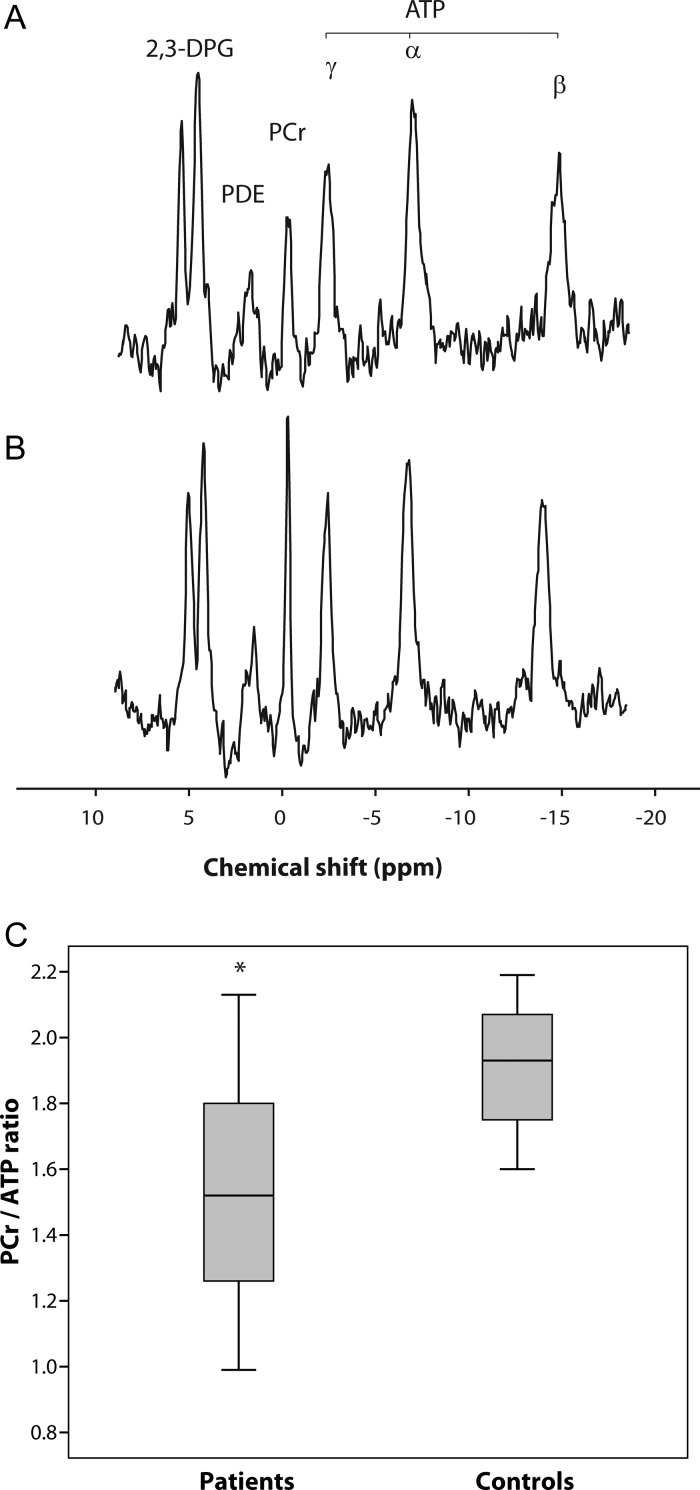

Myocardial bioenergetics

The PCr/ATP ratio was decreased (Figure 3, mean decrease 21%, P < 0.001) in patients (1.51 ± 0.34) compared with controls (1.92 ± 0.20). There were no significant correlations between the PCr/ATP ratio and markers of disease burden or myocardial mass or function. Thirteen patients (59%) had an abnormal PCr/ATP ratio (<1.6) but there were no significant differences in markers of disease burden, cardiac morphology or the function between patients with the PCr/ATP ratio >1.6 and those <1.6.18

Figure 3.

31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Representative spectra from (A) a patient carrying m.3243A>G, with the PCr/ATP ratio of 1.23, and (B) a matched control subject, with the PCr/ATP ratio of 2.10, showing a difference in the PCr concentration. Spectra are presented as acquired before correction for heart rate, flip angle and blood content. (C) A box plot of range and quartiles of the PCr/ATP ratio in patient and control groups. 2,3DPG, 2,3-disphosphoglycerate; PDE, phosphodiesters; PCr, phosphocreatine; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ppm, parts per million; *P < 0.001 compared with controls.

Discussion

This study used a combined approach of comprehensive cardiac MRI and 31P MRS to examine myocardial morphology, function, and bioenergetics in 22 patients harbouring the m.3243A>G mutation without clinical cardiac involvement. The major findings in these patients compared with age- and gender-matched controls were: (i) LVMI was greater and was a more sensitive indicator of subtle cardiac hypertrophy than the LV mass; (ii) concentric remodelling occurred in the absence of hypertension or diabetes mellitus; (iii) altered systolic myocardial strains occurred, with reduced longitudinal shortening and increased peak torsion, in the absence of global systolic or diastolic dysfunction; (iv) early changes in the cardiac morphology and strains were associated with increased mtDNA mutation load and NMDAS score; and (v) PCr/ATP ratio was reduced, but did not correlate with structural or functional cardiac indices or markers of disease burden.

Cardiac morphology and function

Patients in this study displayed concentric hypertrophic remodelling, as evidenced by increased M/V ratio and wall thicknesses, which were independent of diabetic or hypertensive status. Reductions in the end-systolic and end-diastolic blood pool volumes, consistent with concentric remodelling, resulted in decreased stroke volume and index in this study. The finding of significantly elevated heart rate, that ensured no difference in the cardiac output or index was however intriguing and has not been previously reported in this patient group. No likely culprit medications were identified in the patient group as a whole and the possibility of a relationship to the underlying disease process remains to be explored. The pattern of concentric hypertrophic remodelling observed in this study is similar to that in normal ageing where reduced ventricular volumes and increased M/V ratio, with a minimal change in the LV mass, have been linked to adverse cardiac outcomes, particularly when present in those <65 years of age.25

Small studies have suggested differing estimates of the prevalence of LVH in m.3243A>G mutation carriers.4,6 This study, performed in patients without preceding evidence of cardiac involvement, demonstrates the critical importance of referencing LV mass to the BSA. Although not reaching statistical significance, patients had smaller body mass, height, BMI and BSA compared with controls. The LV mass was significantly increased in patients, but only when indexed to BSA. Taken together, these findings suggest that previous cohort studies that used absolute measures of the LV mass and did not employ indexation may have underestimated the number of patients with an increased indexed LV mass. While standard definitions of LVH should be used, this implies that the frequency of LVH in patients, which is potentially amenable to treatment, may be higher than previously indicated.4 A larger cross-sectional study would be required to investigate this issue.

Myocardial strains and torsion

Consistent with LVH in other clinical contexts,15,28 concentric remodelling in this study was associated with reduced longitudinal shortening. In healthy ageing and patients with diabetes mellitus or neuromuscular diseases, circumferential strain is reduced, and associated with reduced longitudinal shortening.25,28,29 In this study, endocardial and whole wall circumferential strains tended to be reduced in patients without reaching statistical significance. The higher mutation load and NMDAS score, indicative of greater disease burden, did however correlate with increased LVMI and reduced endocardial circumferential strain.

Increased torsion and/or TSR, often with reduced longitudinal shortening, have been reported in patients with LVH secondary to HCM,15,16 or conditions of increased afterload including aortic stenosis and hypertension.14,30 In all cases, such changes in torsion, TSR and longitudinal shortening are believed to be due to a reduction in the contractile function in the subendocardium compared with subepicardium.14 Recently Chung et al.31 demonstrated increased torsion in the absence of morphological cardiac disease in diabetic patients. Although the pathophysiology of diabetes in mitochondrial disease is distinct,32 our results of increased torsion and TSR without significant change in circumferential strains concur with these findings and those reported in HCM mutation carriers without LVH.16 Additionally, as in our cohort, both these studies reported isolated systolic abnormalities of torsion with no difference in controls in the rate of torsion dissipation during diastole, or basic measures of diastolic function. Myocardial perfusion defects could contribute to this increased torsion, with abnormalities of subendocardial arterioles in HCM hearts,33 and small vessel disease in diabetes. Such abnormalities could similarly be responsible for the differences in myocardial deformation in our study. However, our patients also demonstrated significant reductions in end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes, yielding smaller radii for the myocardium. Increased torsion could have resulted from the additional dominance this gave to the subepicardium.34 To distinguish between these explanations would require a measure of perfusion at the subendocardium.

Disease burden

Cardiac involvement is an important prognostic factor in mitochondrial disease since complications of cardiomyopathy are a frequent cause of premature death. Yet the pathophysiological mechanisms linking the m.3243A>G mutation to LVH and cardiomyopathy remain unknown. Our group has previously shown that urinary mutation load is the best predictor of overall clinical outcome in the m.3243A>G mutation carriers.21 In this study, we report for the first time a correlation between the urinary mutation load and cardiac involvement specifically, as evidenced by increased LVMI. The NMDAS score correlated strongly with both the urinary mutation load and the LVMI. These important findings support the primary importance of mtDNA mutations in the changes observed in cardiac morphology, and may support more intensive cardiac evaluation of patients with higher mutation loads and/or NMDAS scores.

Cardiac bioenergetics

Reductions in the PCr/ATP ratio, assessed non-invasively using 31P MRS, have prognostic importance in diverse forms of cardiomyopathy.18 Indeed myocardial energy depletion has been proposed as a critical mechanism linking sarcomeric defects to hypertrophy in the HCM.17 Our study confirms the findings of a study in m.3243A>G mutation carriers, which found that the PCr/ATP ratio was significantly reduced.19 However, we were unable to detect any correlation between the cardiac bioenergetic defect and MRI-based parameters of myocardial structure or function, or markers of disease burden in patients without clinical cardiac disease. In different forms of inherited cardiomyopathy, several groups have suggested the primacy of bioenergetic defects by detection of abnormalities in mutation carriers without evidence of LVH.17,35 However, we detected significant differences in cardiac remodelling, known itself to cause a reduction in the PCr/ATP ratio and potentially explaining the lack of correlation with other parameters. The PCr/ATP ratio does not in isolation appear to have a prognostic value in the detection of early cardiac remodelling in patients harbouring the m.3243A>G mutation, but a larger natural history study would be required to confirm this suggestion.

Clinical implications

There are several clinical implications from our findings. First, the indexing of measures of the LV mass to BSA or the end-diastolic volume is essential to detect early concentric remodelling in patients harbouring the m.3243A>G mutation. Cardiac involvement may be more prevalent than previously suspected. Secondly, patients with a higher urinary mutation load, or NMDAS score, may be at an increased risk of developing cardiomyopathy, supporting more frequent cardiac screening. Finally, natural history studies of pathogenesis and eventual clinical therapeutic trials are dependent on an ability to identify the earliest biomechanical changes attributable to the m.3243A>G mutation. We have shown for the first time increased torsion and abnormal myocardial strains in this cohort, and suggest that the measurement of LV mechanics may be useful in assessing disease progression and response to intervention.

Limitations

Although this study is the largest cardiac MRI-based investigation performed to date in this patient group, it remains limited in the sample size and was not designed to investigate pathogenetic mechanisms or disease progression. Cardiac involvement in mitochondrial disease is linked to clinical outcomes, yet we acknowledge that the prognostic importance of the changes we describe must be determined through longitudinal studies. We studied a relatively homogenous cohort of patients, harbouring the single commonest mtDNA point mutation, without known cardiac involvement; such patients account for ∼25% of our specialist clinic attendees yet we recognize that our findings may not be generalizable to all patients with mtDNA point mutations. We did not perform echocardiography in controls and so cannot use age- and gender-matching to compare echocardiographic and MRI-derived parameters, particularly with regard to the diastolic dysfunction. Longitudinal shortening was used to provide a global measure of the long-axis function rather than the longitudinal strain, which would require additional tagged long-axis slices. Similarly, in an already extensive MRI protocol, we did not study flow-based analyses of the diastolic function or first-pass perfusion. Finally, we did not perform LGE imaging in controls and cannot exclude the presence of focal fibrosis in these individuals, although the probability of this is very low.

Conclusions

Concentric remodelling is prevalent in patients harbouring the m.3243A>G mutation and occurs in association with characteristic changes in systolic intramyocardial strains and torsion. These findings, which are closely related to urinary mutation load and disease burden, occur in patients without existing evidence of cardiac involvement, and may provide an early marker of myocardial pathology, enabling future studies of pathogenesis and intervention.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at European Heart Journal – Cardiovascular Imaging online.

Funding

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust [BH092142 to M.G.D.B., 096919Z/11/Z to P.F.C., D.M.T. and R.W.T., 074454/Z/04/Z to D.M.T. and R.W.T.]; the Medical Research Council [G1100160 to K.G.H,. G0601943 to D.M.T. and G0800674 to P.F.C., D.M.T. and R.W.T.]; the UK National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre for Ageing and Age-related Diseases award to Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust [for P.F.C., D.M.T., G.S.G., control data and cardiac tagging software]; the British Heart Foundation [CH/07/001 to B.D.K.]; and the UK NHS Specialized Services and Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust that support the ‘Rare Mitochondrial Disorders of Adults and Children’ Diagnostic Service [http://www.mitochondrialncg.nhs.uk]. Magnetic resonance imaging data from four patients in this study were collected during the screening phase of a commercially sponsored study funded by Penwest Pharmaceuticals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank patients and volunteers involved in this study. We are grateful to Louise Morris, Tamsin Gaudie and Tim Hodgson, Research Radiographers, and to Ben Dixon and Rajiv Das for assistance with image analysis.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Elliott HR, Samuels DC, Eden JA, Relton CL, Chinnery PF. Pathogenic mitochondrial DNA mutations are common in the general population. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:254–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirano M, Pavlakis SG. Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes (MELAS): current concepts. J Child Neurol. 1994;9:4–13. doi: 10.1177/088307389400900102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anan R, Nakagawa M, Miyata M, Higuchi I, Nakao S, Suehara M, et al. Cardiac involvement in mitochondrial diseases. A study on 17 patients with documented mitochondrial DNA defects. Circulation. 1995;91:955–61. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.4.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Majamaa-Voltti K, Peuhkurinen K, Kortelainen ML, Hassinen IE, Majamaa K. Cardiac abnormalities in patients with mitochondrial DNA mutation 3243A > G. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2002;2:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-2-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmgren D, Wahlander H, Eriksson B, Oldfors A, Holme E, Tulinius M. Cardiomyopathy in children with mitochondrial disease; clinical course and cardiological findings. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:280–8. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00387-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vydt TCG, de Coo RFM, Soliman OII, Ten Cate FJ, van Geuns R-JM, Vletter WB, et al. Cardiac involvement in adults with m.3243A > G MELAS gene mutation. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:264–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.07.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Majamaa-Voltti K, Turkka J, Kortelainen ML, Huikuri H, Majamaa K. Causes of death in pedigrees with the 3243A > G mutation in mitochondrial DNA. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:209–11. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.122648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, et al. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration With the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:e1–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duboc D, Meune C, Lerebours G, Devaux JY, Vaksmann G, Becane HM. Effect of perindopril on the onset and progression of left ventricular dysfunction in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:855–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myerson SG, Montgomery HE, World MJ, Pennell DJ. Left ventricular mass: reliability of M-mode and 2-dimensional echocardiographic formulas. Hypertension. 2002;40:673–8. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000036401.99908.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yilmaz A, Gdynia HJ, Baccouche H, Mahrholdt H, Meinhardt G, Basso C, et al. Cardiac involvement in patients with Becker muscular dystrophy: new diagnostic and pathophysiological insights by a CMR approach. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2008;10:50. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-10-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pfeffer G, Majamaa K, Turnbull DM, Thorburn D, Chinnery PF. Treatment for mitochondrial disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD004426. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004426.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lumens J, Delhaas T, Arts T, Cowan BR, Young AA. Impaired subendocardial contractile myofiber function in asymptomatic aged humans, as detected using MRI. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H1573–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00074.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Der Toorn A, Barenbrug P, Snoep G, Van Der Veen FH, Delhaas T, Prinzen FW, et al. Transmural gradients of cardiac myofiber shortening in aortic valve stenosis patients using MRI tagging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1609–15. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00239.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young AA, Kramer CM, Ferrari VA, Axel L, Reichek N. Three-dimensional left ventricular deformation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1994;90:854–67. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.2.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russel IK, Brouwer WP, Germans T, Knaapen P, Marcus JT, van der Velden J, et al. Increased left ventricular torsion in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutation carriers with normal wall thickness. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011;13:3. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-13-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crilley JG, Boehm EA, Blair E, Rajagopalan B, Blamire AM, Styles P, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy due to sarcomeric gene mutations is characterized by impaired energy metabolism irrespective of the degree of hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1776–82. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)03009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neubauer S, Krahe T, Schindler R, Horn M, Hillenbrand H, Entzeroth C, et al. 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy in dilated cardiomyopathy and coronary artery disease. Altered cardiac high-energy phosphate metabolism in heart failure. Circulation. 1992;86:1810–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.6.1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lodi R, Rajagopalan B, Blamire AM, Crilley JG, Styles P, Chinnery PF. Abnormal cardiac energetics in patients carrying the A3243G mtDNA mutation measured in vivo using phosphorus MR spectroscopy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2004;1657:146–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schaefer AM, Phoenix C, Elson JL, McFarland R, Chinnery PF, Turnbull DM. Mitochondrial disease in adults: a scale to monitor progression and treatment. Neurology. 2006;66:1932–4. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219759.72195.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whittaker RG, Blackwood JK, Alston CL, Blakely EL, Elson JL, McFarland R, et al. Urine heteroplasmy is the best predictor of clinical outcome in the m.3243A > G mtDNA mutation. Neurology. 2009;72:568–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000342121.91336.4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schar M, Vonken EJ, Stuber M. Simultaneous B(0)- and B(1)+-map acquisition for fast localized shim, frequency, and RF power determination in the heart at 3 T. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:419–26. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanhamme L, Van Huffel S, Van Hecke P, van Ormondt D. Time-domain quantification of series of biomedical magnetic resonance spectroscopy signals. J Magn Reson. 1999;140:120–30. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones DE, Hollingsworth K, Fattakhova G, MacGowan G, Taylor R, Blamire A, et al. Impaired cardiovascular function in primary biliary cirrhosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G764–73. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00501.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng S, Fernandes VR, Bluemke DA, McClelland RL, Kronmal RA, Lima JA. Age-related left ventricular remodeling and associated risk for cardiovascular outcomes: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:191–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.819938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hundley WG, Bluemke D, Bogaert JG, Friedrich MG, Higgins CB, Lawson MA, et al. Society for cardiovascular magnetic resonance guidelines for reporting cardiovascular magnetic resonance examinations. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2009;11:5. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alfakih K, Plein S, Thiele H, Jones T, Ridgway JP, Sivananthan MU. Normal human left and right ventricular dimensions for MRI as assessed by turbo gradient echo and steady-state free precession imaging sequences. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;17:323–9. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fonseca CG, Dissanayake AM, Doughty RN, Whalley GA, Gamble GD, Cowan BR, et al. Three-dimensional assessment of left ventricular systolic strain in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, diastolic dysfunction, and normal ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:1391–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.07.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hor KN, Wansapura J, Markham LW, Mazur W, Cripe LH, Fleck R, et al. Circumferential strain analysis identifies strata of cardiomyopathy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a cardiac magnetic resonance tagging study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1204–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang SJ, Lim HS, Choi BJ, Choi SY, Hwang GS, Yoon MH, et al. Longitudinal strain and torsion assessed by two-dimensional speckle tracking correlate with the serum level of tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-1, a marker of myocardial fibrosis, in patients with hypertension. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21:907–11. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chung J, Abraszewski P, Yu X, Liu W, Krainik AJ, Ashford M, et al. Paradoxical increase in ventricular torsion and systolic torsion rate in type I diabetic patients under tight glycemic control. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:384–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maassen JA, LM TH, Van Essen E, Heine RJ, Nijpels G, Jahangir Tafrechi RS, et al. Mitochondrial diabetes: molecular mechanisms and clinical presentation. Diabetes. 2004;53:S103–9. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2007.s103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwartzkopff B, Mundhenke M, Strauer BE. Alterations of the architecture of subendocardial arterioles in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and impaired coronary vasodilator reserve: a possible cause for myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:1089–96. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arts T, Reneman RS, Veenstra PC. A model of the mechanics of the left ventricle. Ann Biomed Eng. 1979;7:299–318. doi: 10.1007/BF02364118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lodi R, Rajagopalan B, Blamire AM, Cooper JM, Davies CH, Bradley JL, et al. Cardiac energetics are abnormal in Friedreich ataxia patients in the absence of cardiac dysfunction and hypertrophy: an in vivo 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;52:111–9. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00357-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.