Summary

Drug resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) undermine tuberculosis (TB) control. Streptolydigin is a broadly effective antibiotic which inhibits RNA polymerase, similarly to rifampicin, a key drug in current TB chemotherapeutic regimens. Due to a vastly improved chemical synthesis streptolydigin and derivatives are being promoted as putative TB drugs. The Microplate Alamar Blue Assay revealed that Streptococcus salivarius and Mycobacterium smegmatis were susceptible to streptolydigin with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of 1.6 mg/L and 6.25 mg/L, respectively. By contrast, the MICs of streptolydigin and two derivatives, streptolydiginone and dihydrostreptolydigin, against Mtb were ≥100 mg/L demonstrating that Mtb is resistant to streptolydigin in contrast to previous reports. Further, a porin mutant of M. smegmatis is resistant to streptolydigin indicating that porins mediate uptake of streptolydigin across the outer membrane. Since the RNA polymerase is a validated drug target in Mtb and porins are required for susceptibility of M. smegmatis, the absence of MspA-like porins probably contributes to the resistance of Mtb to streptolydigin. This study shows that streptolydigin is not a suitable drug in TB treatment regimens.

Keywords: drug resistance, RNA polymerase, inhibitor, porins, permeability

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the causative agent of tuberculosis in humans, kills approximately 1.5 million people each year1. Infections with drug-resistant strains are increasing world-wide1. It is, therefore, critical to identify new compounds or new variants of old drugs with activity against drug-resistant strains. Streptolydigin, a broadly effective antibiotic naturally produced by Streptomyces lydicus, inhibits RNA polymerase (RNAP) during the nucleotide addition step2, 3. Rifampicin is a key first-line drug against Mtb, used for almost 50 years in TB chemotherapy; however, resistance to this drug is increasing. Both drugs inhibit RNA polymerase, but bind to different sites and have different mechanisms of action4–6. Rifampicin-resistant bacteria are often susceptible to streptolydigin7, which has, therefore, been proposed as an alternative to rifampicin in treating resistant strains of Mtb8, 9. An additional advantage of streptolydigin is its low toxicity, with an LD50 of 533 mg/kg in rats2. To facilitate the development of streptolydigin as an antibiotic in tuberculosis chemotherapy, Pronin and co-workers synthesized streptolydigin using a new strategy with fewer steps (15 compared to 24 in the older method)8, 9. Several derivatives of streptolydigin were also synthesized, with varying activities in vitro against Thermus aquaticus (Taq) RNAP, a well-characterized representative of bacterial RNA polymerases 9.

Previously, streptolydigin was shown to have a minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 15 and 25 mg/L against Mtb and M. smegmatis in liquid cultures using turbidity measurements2. However, turbidity measurements to determine drug efficacies against Mtb are notoriously unreliable10. The microplate Alamar Blue assay (MABA) is now the standard method of susceptibility measurements in the tuberculosis field and is also utilized in whole cell-based high throughput screens to identify growth inhibitors of Mtb11, 12. The Alamar Blue reagent is used as an indicator of cellular growth and viability and has been extensively validated for Mtb by comparison to the well-established BACTEC 460 system13. Therefore, we used the MABA to determine the MIC of streptolydigin and its derivatives. Our aim was to verify the activity of streptolydigin against Mtb using state of the art methods and determine whether the newly synthesized derivatives had increased potency. We determined the in vivo efficacy of synthesized streptolydigin and the derivatives streptolydiginone and dihydrostreptolydigin against Mycobacterium smegmatis and Mtb, using natural streptolydigin as a control.

Materials and Methods

Cell growth experiments and MABA were performed as previously described14, 15. M. smegmatis cultures were grown to mid-log phase in standard liquid medium (Middlebrook 7H9 (Difco) with 0.2% glycerol) containing 0.02% tyloxapol to promote dispersed growth. Mtb cultures were supplemented with 10% (vol./vol.) OADC (oleic acid, albumin, dextrose and catalase) (BD). Streptococcus salivarius was cultured in Bacto Tryptic Soy Broth (BD). Cells were transferred to a microplate containing twofold serial dilutions of the compound to be tested. After appropriate drug exposure times (S. salivarius, 4 hours; M. smegmatis, 16 hours; Mtb, 5 days), Alamar Blue (Invitrogen) was added according to manufacturer instructions and allowed to react until a visible color change was observed compared to negative controls. Dye conversion was measured fluorometrically (excitation 530nm, emission 590nm) using a plate reader (Biotek Synergy HT). Streptolydigin is most stable in ethanol out of the solvents which yielded the highest activity2. The concentration of ethanol alone which does not inhibit mycobacterial growth was determined to be 1.25% by MABA. Hence, we used a 1% final concentration of ethanol to determine the MIC of streptolydigin. The maximum concentration of streptolydigin or its derivatives tested in this study was 200 mg/L.

Results and Discussion

Validation of activity of streptolydigin and its derivatives against model bacteria

To assess the activity of the natural streptolydigin sample, we tested the efficacy against Streptococcus salivarius strain MN8248 (from Dr. Moon Nahm) and found a MIC of 1.6 mg/L, which is within the range of activities reported for other Streptococcus species2. We determined the MIC of both natural and synthetic streptolydigin against M. smegmatis to be 6.25 mg/L, about four-fold lower than previously reported (Table1, Figure 1)2.

TABLE 1.

Efficacies of antibiotics against mycobacteria and S. salivarius (MIC90, in mg/L)

| Drug | MW (g/mol) | Partition coefficient | M. tuberculosis | M. smegmatis | M. smegmatis | S. salivarius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| H37Rv wt | SMR5 wt | ML16 ΔmspACD | MN8248 wt | |||

| Streptolydigin natural | 600.7 | 1.41 | 200 | 6.25 | >200 | 1.6 |

| Streptolydigin synthetic | 600.7 | 1.41 | 100 | 6.25 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Streptolydiginone | 486.6 | 0.99 | 200 | 100 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Dihydrostreptolydigin | 602.7 | 1.7 | >200 | 50 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Ampicillin | 349.4 | 0.43 | 160 | 62.5 | >200 | 0.06 |

Partition coefficients were calculated using the XlogP2 server 25. MW: molecular weight; n.d.: not determined

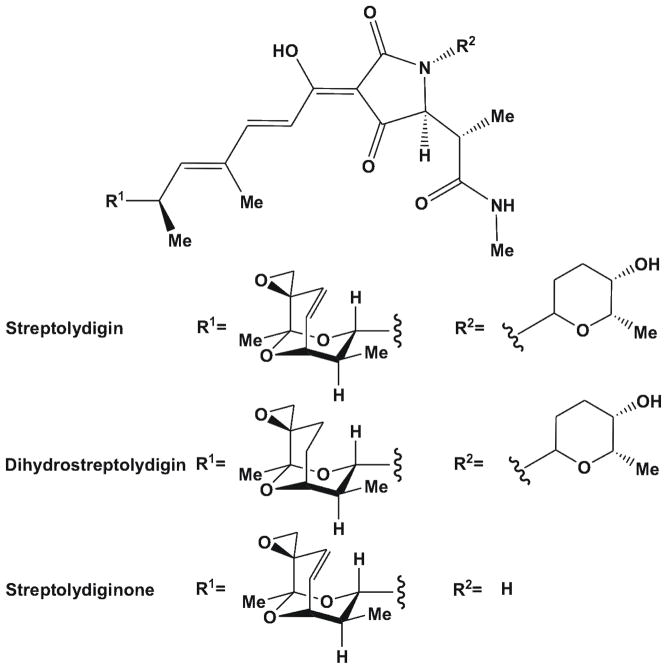

Figure 1.

Structures of streptolydigin and the derivatives dihydrostreptolydigin and streptolydiginone.

Although streptolydiginone and dihydrostreptolydigin had lower activities against Taq RNAP compared to streptolydigin9, structural and chemical changes may have improved permeability across the outer membrane, a key resistance determinant in mycobacteria16. The partition coefficients of compounds correlate with hydrophobicity and indicated that dihydrostreptolydigin may be able to cross membranes more efficiently than streptolydigin (Table 1). Further, streptolydiginone and dihydrostreptolydigin had similar efficacies against S. salivarius, but different in vitro activities against RNAP, suggesting there may be secondary targets9. Using the MABA we determined the MICs of streptolydiginone and dihydrostreptolydigin for M. smegmatis to be 100 mg/L and 50 mg/L, respectively (Table 1) demonstrating that these modifications rendered streptolydigin less effective against M. smegmatis.

Activity of streptolydigin and its derivatives against M. tuberculosis

We used the MABA to determine the MIC of natural streptolydigin against Mtb grown in standard medium to be 200 mg/L (Table 1). The same MIC was obtained using the Nitrate Reductase Assay (NRA)17 (data not shown). Because the albumin in the OADC supplement is capable of binding and sequestering a wide variety of compounds including antibiotics18, we repeated the MABA using the minimal, albumin-free Sauton’s Medium19. However, even in the absence of albumin, the MIC of streptolydigin for Mtb was 200 mg/L, nearly 14-fold higher compared to previous results2. It should be noted that streptolydigin in medium alone did not show any autofluorescence which might interfere with the MABA. Since mycobacteria are known to form clumps in liquid media even in the presence of detergents, rendering turbidity measurements inaccurate10, we believe the discrepancy between our results and those previously published have been caused by unreliable turbidometric measurements in the earlier experiments2. Additionally, we determined the MIC of synthetic streptolydigin, streptolydiginone and dihydrostreptolydigin against Mtb to be 100 mg/L, 200 mg/L and greater than 200 mg/L, respectively (Table 1). These measurements showed that the modifications of these two derivatives did not improve the efficacy of streptolydigin against Mtb, similar to the results obtained for M. smegmatis. The NIH Tuberculosis Antimicrobial Acquisition and Coordinating Facility (TAACF) defined primary hits as having a MIC of less than 10 mg/L11. The MICs of streptolydigin and its derivatives for Mtb are well above this limit indicating that these compounds would not be considered as viable leads for TB drugs.

Role of porins in mycobacterial susceptibility to streptolydigin

We wondered whether the low permeability of the outer membrane and its low content of porins 16 might contribute to the resistance of Mtb to streptolydigin compared to M. smegmatis. It has been shown that general porins mediate antibiotic uptake in M. smegmatis14, 20, but no general porins are known in Mtb21. A molecular model of the major M. smegmatis porin MspA indicates that streptolydigin is small enough to pass through the constriction zone of MspA. To examine whether the absence of MspA-like porins is correlated with resistance to streptolydigin, we tested the activity of streptolydigin against an M. smegmatis triple porin mutant, lacking the general porins MspA, MspC and MspD (ML16, ΔmspA ΔmspC ΔmspD). As a control, we determined the MIC for ampicillin against the porin mutant ML16, which has previously been shown to be more resistant to ampicillin than wild-type M. smegmatis14. In preliminary dose-response curves, we determined the activity of ampicillin against mycobacteria and S. salivarius. The MICs of ampicillin were 0.06 mg/L, 62.5 mg/L and 160 mg/L for S. salivarius, M. smegmatis and Mtb, respectively (Table 1). These results are consistent with previous measurements14, 22. The MICs for streptolydigin and ampicillin against ML16 were both greater than 200 mg/L (Table 1). Expression of mspA in Mtb did not increase streptolydigin susceptibility (data not shown), likely due to very low MspA levels in Mtb23. We conclude that porins are required for susceptibility of M. smegmatis to streptolydigin, probably by mediating its uptake across the outer membrane.

Conclusions

In this study, we showed that Mtb is resistant to streptolydigin, while M. smegmatis is susceptible. The porin MspA and its paralogs are a major susceptibility factor, promoting streptolydigin uptake in M. smegmatis. Hence, the absence of MspA-like porins in Mtb may contribute to its resistance to streptolydigin. However, reduced uptake across the outer membrane is only efficient in mediating drug resistance in combination with other mechanisms such as drug efflux24. It is unknown whether strepotolydigin is a substrate of drug efflux pumps in Mtb. In conclusion, these results show that neither streptolydigin nor its derivatives are useful antibiotics to treat tuberculosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kozmin for samples of streptolydigin and its derivatives. Streptococcus salivarius MN8248 was obtained from Dr. Nahm. We thank members of the Mycolab for helpful discussions.

Funding

JLR is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) training grant T32 AI7493-17. This work was supported by the NIH grant R01 AI074805 to MN.

Abbreviations

- wt

wild-type

- MABA

microplate alamar blue assay

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.WorldHealthOrganization. Global tuberculosis control. WHO report 2012. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deboer C, Dietz A, Savage GM, Silver WS. Streptolydigin, a new antimicrobial antibiotic. I. Biologic studies of streptolydigin. Antibiot Ann. 1955;3:886–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Temiakov D, Zenkin N, Vassylyeva MN, Perederina A, Tahirov TH, Kashkina E, Savkina M, Zorov S, Nikiforov V, Igarashi N, Matsugaki N, Wakatsuki S, Severinov K, Vassylyev DG. Structural basis of transcription inhibition by antibiotic streptolydigin. Mol Cell. 2005;19:655–666. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho MX, Hudson BP, Das K, Arnold E, Ebright RH. Structures of RNA polymerase-antibiotic complexes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:715–723. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuske S, Sarafianos SG, Wang X, Hudson B, Sineva E, Mukhopadhyay J, Birktoft JJ, Leroy O, Ismail S, Clark AD, Jr, Dharia C, Napoli A, Laptenko O, Lee J, Borukhov S, Ebright RH, Arnold E. Inhibition of bacterial RNA polymerase by streptolydigin: stabilization of a straight-bridge-helix active-center conformation. Cell. 2005;122:541–552. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trinh V, Langelier MF, Archambault J, Coulombe B. Structural perspective on mutations affecting the function of multisubunit RNA polymerases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:12–36. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.70.1.12-36.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Neill A, Oliva B, Storey C, Hoyle A, Fishwick C, Chopra I. RNA polymerase inhibitors with activity against rifampin-resistant mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3163–3166. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.11.3163-3166.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pronin SV, Kozmin SA. Synthesis of streptolydigin, a potent bacterial RNA polymerase inhibitor. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14394–14396. doi: 10.1021/ja107190w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pronin SV, Martinez A, Kuznedelov K, Severinov K, Shuman HA, Kozmin SA. Chemical synthesis enables biochemical and antibacterial evaluation of streptolydigin antibiotics. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:12172–12184. doi: 10.1021/ja2041964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anton V, Rouge P, Daffe M. Identification of the sugars involved in mycobacterial cell aggregation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;144:167–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ananthan S, Faaleolea ER, Goldman RC, Hobrath JV, Kwong CD, Laughon BE, Maddry JA, Mehta A, Rasmussen L, Reynolds RC, Secrist JA, 3rd, Shindo N, Showe DN, Sosa MI, Suling WJ, White EL. High-throughput screening for inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2009;89:334–353. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franzblau SG, DeGroote MA, Cho SH, Andries K, Nuermberger E, Orme IM, Mdluli K, Angulo-Barturen I, Dick T, Dartois V, Lenaerts AJ. Comprehensive analysis of methods used for the evaluation of compounds against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2012;92:453–488. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2012.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Collins L, Franzblau SG. Microplate alamar blue assay versus BACTEC 460 system for high-throughput screening of compounds against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1004–1009. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danilchanka O, Pavlenok M, Niederweis M. Role of porins for uptake of antibiotics by Mycobacterium smegmatis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3127–3134. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00239-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franzblau SG, Witzig RS, McLaughlin JC, Torres P, Madico G, Hernandez A, Degnan MT, Cook MB, Quenzer VK, Ferguson RM, Gilman RH. Rapid, low-technology MIC determination with clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates by using the microplate Alamar Blue assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:362–366. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.362-366.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niederweis M, Danilchanka O, Huff J, Hoffmann C, Engelhardt H. Mycobacterial outer membranes: in search of proteins. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar M, Khan IA, Verma V, Qazi GN. Microplate nitrate reductase assay versus Alamar Blue assay for MIC determination of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:939–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Wolf FA, Brett GM. Ligand-binding proteins: their potential for application in systems for controlled delivery and uptake of ligands. Pharmacol Reviews. 2000;52:207–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersen P, Askgaard D, Ljungqvist L, Bennedsen J, Heron I. Proteins released from Mycobacterium tuberculosis during growth. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1905–1910. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.1905-1910.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stephan J, Mailaender C, Etienne G, Daffe M, Niederweis M. Multidrug resistance of a porin deletion mutant of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4163–4170. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.11.4163-4170.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song H, Huff J, Janik K, Walter K, Keller C, Ehlers S, Bossmann SH, Niederweis M. Expression of the ompATb operon accelerates ammonia secretion and adaptation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to acidic environments. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:900–918. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fass RJ, Barnishan J. Comparison of antimicrobial in vitro activities against Streptococcus pneumoniae independent of MIC susceptibility breakpoints using MIC frequency distribution curves, scattergrams and linear regression analyses. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;48:609–615. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.5.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mailaender C, Reiling N, Engelhardt H, Bossmann S, Ehlers S, Niederweis M. The MspA porin promotes growth and increases antibiotic susceptibility of both Mycobacterium bovis BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology. 2004;150:853–864. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26902-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarlier V, Nikaido H. Mycobacterial cell wall: structure and role in natural resistance to antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;123:11–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang R, Gao Y, Lai L. Calculating partition coefficient by atom-additive method. Perspect Drug Discovery Des. 2000;19:47–66. [Google Scholar]