Abstract

Objectives

To address the question of whether, on a population level, early detection and amplification improve outcomes of children with hearing impairment.

Design

All families of children who were born between 2002 and 2007, and who presented for hearing services below 3 years of age at Australian Hearing pediatric centers in New South Wales, Victoria and Southern Queensland were invited to participate in a prospective study on outcomes. Children’s speech, language, functional and social outcomes were assessed at 3 years of age, using a battery of age-appropriate tests. Demographic information relating to the child, family, and educational intervention was solicited through the use of custom-designed questionnaires. Audiological data were collected from the national database of Australian Hearing and records held at educational intervention agencies for children. Regression analysis was used to investigate the effects of each of 15 predictor variables, including age of amplification, on outcomes.

Results

Four hundred and fifty-one children enrolled in the study, 56% of whom received their first hearing-aid fitting before 6 months of age. Based on clinical records, 44 children (10%) were diagnosed with auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder. There were 107 children (24%) reported to have additional disabilities. At 3 years of age, 317 children (70%) were hearing-aid users and 134 children (30%) used cochlear implants. Based on parent reports, about 71% used an aural/oral mode of communication, and about 79% used English as the spoken language at home. Children’s performance scores on standardized tests administered at 3 years of age were used in a factor analysis to derive a global development factor score. On average, the global score of hearing-impaired children was more than one standard deviation (SD) below the mean of normal-hearing children at the same age. Regression analysis revealed that five factors, including female gender, absence of additional disabilities, less severe hearing loss, higher maternal education; and for children with cochlear implants, earlier age of switch-on; were associated with better outcomes at the 5% significance level. Whereas the effect of age of hearing aid fitting on child outcomes was weak, a younger age at cochlear implant switch-on was significantly associated with better outcomes for children with cochlear implants at 3 years of age.

Conclusions

Fifty-six percent of the 451 children were fitted with hearing aids before 6 months of age. At 3 years of age, 134 children used cochlear implants and the remaining children used hearing aids. On average, outcomes were well below population norms. Significant predictors of child outcomes include: presence/absence of additional disabilities, severity of hearing loss, gender, maternal education; together with age of switch-on for children with cochlear implants.

Keywords: outcomes, hearing-impaired children, language, predictors, cochlear implants, hearing aids, hearing loss, population study

Introduction

Many children with congenital permanent hearing impairment have difficulties acquiring speech, language and literacy. In 2001, the United States of America Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) noted that “the average deaf student graduates from high school with language and academic achievement levels below those of the average fourth-grade student with normal hearing. Average reading scores for hard-of-hearing students graduating from high school are at the fifth grade level.” (Helfand et al. 2001).

With the advent of portable, reliable screening technologies such as otoacoustic emissions and evoked potential testing in the 1990s, it became possible to implement automated hearing screening during the postnatal period on a population basis. This screening resulted in identification of hearing loss soon after birth, allowing the early provision of treatment through amplification and management through early educational programs. In this paper, auditory intervention refers to diagnosis of hearing loss and fitting of hearing aids following diagnosis; and educational intervention refers to enrolment in early educational programs. Several observational studies have reported that children who enrolled in educational intervention before 6 months of age developed better language skills than those who enrolled at a later time (Calderon & Naidu 2000; Yoshinaga-Itano et al. 1998). This provided a driving force for widespread implementation of universal newborn hearing screening (UNHS) internationally (Tann et al. 2009). Despite this large-scale adoption of UNHS, serious evidence gaps in regards to its efficacy remain.

As expounded in a systematic review conducted by the USPSTF in 2001 (Thompson et al. 2001), previous studies have methodological limitations such as the use of convenience samples, non-blinded assessments, reliance on parent report tools, and lack of information on attrition and follow-up, amongst others. The task force report rated the strength of evidence linking early treatment to improved language function as “inconclusive”. The review was subsequently updated in 2008 (Nelson et al. 2008) with two additional studies (Kennedy et al. 2006; Wake et al. 2005). Kennedy et al. (2006) evaluated the language outcomes of 120 children born in the mid-1990s in areas of England with and without UNHS. At 8 years of age (mean: 7.9 years; range: 5.4 – 11.7 years), the children whose hearing loss was detected via UNHS had higher receptive language scores than children whose hearing loss was detected later (difference in mean z scores, 0.56; p = 0.04), but there were no significant difference between the two groups in expressive language ability or in speech production ability. Similar findings were reported when children were categorised according to whether their hearing loss was diagnosed before or after 9 months of age.Wake et al. (2005) reported outcomes at 7 – 8 years of age for 86 children born in a region exposed to targeted newborn hearing screening in Australia. They indicated that mean language and reading scores did not vary significantly by age of diagnosis. More recently, a population study in the Netherlands (Korver et al. 2010) reported outcomes of 150 children born between 2003 and 2005 who were assessed using either UNHS at birth or distraction screening at 9 months. The results indicated that there were no significant differences in language scores between the two groups at 4 to 5 years of age. Two of the three population studies revealed no benefit of early detection, and one reported a weak benefit for receptive but not expressive spoken language. These findings do not lend support to the benefit of early detection in improving outcomes.

A major limitation in the population studies published to date is that study cohorts have included very few children who were diagnosed with hearing loss and provided with amplification before 6 months of age (defined by the Joint Committee on Infant Hearing [2007] as the benchmark for early intervention). For example, the cohort reported in Wake et al. (2005) had a mean age of diagnosis at 21.6 months, with only 11 children diagnosed before 6 months of age. The mean age of hearing-aid fitting was 23.2 months. In the Kennedy et al. (2006) study, the cohort of 57 children who were assessed through UNHS were diagnosed before 9 months of age with a median age of hearing-aid fitting at 15 months of age. Even though the degree of hearing loss was confirmed by 9 months of age, only about half of the children had hearing aids around that age (Watkin et al. 2007). In a similar vein, the Korver et al. (2010) study reported that the mean age of hearing-aid fitting for children assessed by UNHS was 15.7 months (SD=14.0), compared to 29.2 months (SD=14.8) for children assessed using distraction screening. Delays in confirmation and amplification after detection might have decreased the potential effect of early detection on children’s outcomes.

To estimate the effect of early identification, it is also necessary to adequately account for multiple factors that have been suggested as contributing to the variance in outcomes across hearing-impaired children. It is generally recognised that the factors include child-related characteristics such as age at fitting (e.g., Pipp-Siegel et al. 2003; Sininger et al. 2010; Worsfold et al. 2010), age at implantation (Artieres et al. 2009; Geers et al. 2008; Niparko et al. 2010), non-verbal cognitive ability (e.g., Geers et al. 2003), presence of additional disabilities (e.g., Dammeyer 2010), severity of hearing loss (e.g., Baudonck et al. 2010; Wake et al. 2004); family characteristics such as communication mode used at home (Eisenberg et al. 2004; Leigh et al. 2009; Percy-Smith et al. 2008), maternal education (Fitzpatrick et al. 2007), socio-economic status (Tobey et al. 2003); and educational intervention characteristics such as communication mode used in education (e.g., Meristo et al. 2007; Jiménez et al. 2009; Geers & Sedey, 2011), and family involvement (e.g., Moeller 2000; Watkin et al. 2007). Across studies, the extent to which various factors were predictive of outcomes varied along with the size and composition of study samples, devices used by children, ages at evaluation, nature of test instruments, and the specific factors selected for inclusion in regression analyses. In the population studies that examined the effect of age of diagnosis, Wake et al. (2005) adjusted scores for severity of hearing loss and non-verbal intelligence; Kennedy et al. (2006) allowed for severity of hearing loss, maternal education and nonverbal cognitive ability; and Korver et al. (2010) adjusted performance scores for maternal education and chronological age at evaluation between the UNHS group and the distraction screening group (mean age was 48 months for the former group and 60 months for the latter group). In Wake et al. (2005), there was a significant decrease in language scores with an increase in severity of hearing loss. However, neither Kennedy et al. (2006) nor Korver et al. (2010) found a significant effect of severity of hearing loss on language outcomes. Although it is generally recognised that the influence of multiple factors, including age of amplification, on child outcomes need to be estimated in the same regression model (Geers et al. 2007), the relatively small sample size in many published studies (e.g. Vohr et al. 2008) prevents an adequate estimation of the effect of age of amplification after controlling for the effects of a wide range of variables in the same cohort.

Furthermore, there are other factors that have not yet been systematically examined in relation to prediction of outcomes due to subject exclusion criteria in some studies. For instance, children with additional disabilities and children in families with a language background other than the native language of the country being studied were excluded in previous studies (e.g., Korver et al. 2010; Wake et al. 2005). Other factors that may be expected to affect outcomes include the prescription used for amplification, the adequacy of fitting for children with different degrees of hearing loss, and the presence or absence of auditory neuropathy (Rance 2005; Roush et al. 2011). In regard to educational intervention, it has been suggested that the use of an aural/oral mode of communication is associated with better child outcomes (Jiménez et al. 2009; Geers & Sedey, 2011), but it is not clear whether children who were not using an aural/oral communication mode at the time of evaluation were the ones who were unsuccessful users of the communication mode. It is not unusual that children with hearing loss change in communication mode in educational intervention during the early years of development (Watson et al. 2008; Hyde & Punch, 2011), and changes may be initiated on the basis of the relative success (or lack of it) with a specific mode. Therefore, changes in communication mode need to be considered in conjunction with the specific mode used at the time of evaluation when quantifying the effect of communication mode in educational intervention on outcomes. The existing literature on children’s outcomes is restricted in the range of factors examined.

The goal of UNHS is to enable early detection and intervention so that long-term outcomes for children with hearing impairment may be improved, at a population level. There is a lack of high-quality evidence regarding the efficacy of early intervention (see systematic reviews by Wolff et al. 2010; Puig et al. 2005). To address the evidence gap, it is necessary to conduct prospective research reporting a comprehensive range of outcomes for contemporary cohorts of children with permanent childhood deafness across the spectrum of severity, drawn from whole populations of children with hearing loss. A prospective study of this type that directly compared development of early and later identified children after identification would not be possible in regions where UNHS has already been implemented. Comparisons across regions with or without UNHS may be confounded by differential access to and quality of auditory intervention across regions. In Australia, all children identified with hearing loss are referred to a single government-funded organization (Australian Hearing [AH]) for the delivery of hearing services governed by a national standard protocol of care. All children also have access to the same range of educational intervention facilities across states, including programs that support auditory-verbal/ oral-aural approaches, total communication, Sign Bilingual (using Auslan and English), and augmentative and alternative communication systems (Australian Hearing, 2005). The circumstances surrounding the roll-out of UNHS programs across Australia (Leigh 2006) provided a window of opportunity to undertake a population-based study investigating the efficacy of early identification in a prospective manner. By seeking to recruit all children diagnosed with hearing loss who were born in the three most populous states of Australia (Queensland, Victoria and New South Wales) between 2002 and 2007, the differential development of UNHS programs across states (see Table 1) provided a cohort of children that were naturally divided according to whether hearing loss was identified early (through UNHS) or later. The Longitudinal Outcomes of Children with Hearing Impairment Study (LOCHI) addresses the need for evidence on the efficacy of early identification. We studied a cohort of children born between 2002 and 2007, drawn from three Australian states, whose hearing loss was identified early or late, depending on location and date of birth.

Table 1.

Univeral newborn hearing screening (UNHS) programs in Australian States and Territories (2002–2007). The technology employed for hearing screening included automated auditory brainstem response (AABR) and transient-evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAE).

| State/Territory | Year UNHS Roll-out Commenced |

Year UNHS Roll-out Completed* |

Percentage of National Births (2002) |

Percentage of National Births (2007) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New South Wales | 2002 | 2003 | 34.5% | 31.4% |

| Victoria | 2005 | Not complete | 24.5% | 24.7% |

| Queensland | 2004 | 2006 | 19.0% | 21.5% |

| Western Australia | 2000 | Not complete | 9.4% | 10.2% |

| South Australia | 2005 | 2006 | 7.0% | 6.9% |

| Tasmania | 2006 | 2009 | 2.4% | 2.3% |

| Australian Capital Territory | 2002 | 2004 | 1.6% | 1.7% |

| Northern Territory | 2008 | 2011 | 1.5% | 1.4% |

year in which >97% of children births completed a screen for hearing

The aims of the study were to: 1) assess the levels of speech and language performance of hearing-impaired children at 3 years of age; and 2) determine the effects of putative child-, family-, and intervention-related factors, including age of amplification, on outcomes at 3 years of age. The study included children with all degrees of hearing loss who received auditory intervention before 3 years of age (children with pre-lingual deafness).

On the basis of current knowledge, it was hypothesized that speech and language outcomes of 3-year-old children who received amplification earlier in life would not be different to those who received later amplification, after allowing for the effects of a range of factors. Effects of relevant predictive factors that might contribute to overall outcomes, based on previous literature, were assessed. The predictors included birthweight, gender, severity of hearing loss, presence or absence of additional disabilities, presence or absence of auditory neuropathy, prescription used for fitting hearing aids, device (hearing aids or cochlear implants), age of cochlear implant switch-on, if applicable, language use at home, communication mode at home and at early educational intervention, changes in communication mode at educational intervention, maternal education and socio-economic status of the family.

METHOD

Participants

All children meeting the inclusion criteria, i.e., born between May 2002 and August 2007 in the states of New South Wales (NSW), Victoria (VIC) and Southern Queensland (QLD) in Australia, who were diagnosed with hearing loss and aided before their 3rd birthday.

Since July 2003, screening coverage has averaged >98% in NSW (New South Wales Health Department 2011). In the period between 2002 and 2007, programs were being rolled out in each of QLD and VIC. By late 2006, coverage was >97% in QLD but had only reached approximately 30% in VIC where there had, however, been a state-wide program referring all children with risk factors for hearing impairment to audiological assessment since 1992 (Leigh 2006. These three states accounted for approximately 78% of all births in Australia during the period from 2002 to 2007 (see Table 1) and provided the sampling frame for this study.

Recruitment commenced in April 2005 and was completed in December 2007. All families that met inclusion criteria were individually invited to participate in the study via the service provision network. Invitations were extended via interpreters with translated material when required. Written informed consent for participation was provided by parents or guardians of child participants. The study was approved by an institutional review board and a population health review board.

On the basis of an expected sample size of 414 children with bilateral permanent childhood hearing impairment (determined according to the expected rates in the general population), we anticipated a statistical power of 0.80 to detect a difference of 0.25 SD in language ability between the early- and later-identified groups, with a two-sided p value of 0.05.

Procedure

Following enrolment and soon after a child turned 3 years of age, a team of trained research speech pathologists conducted direct assessments with the child either at the educational intervention centers normally attended by the child or at the child’s home, as chosen by the parents. During evaluations, children wore hearing aids and/or cochlear implants at their personal settings. The speech pathologists were blinded, as far as possible, to severity of hearing loss and parameter settings in hearing devices. The direct assessments required approximately 2 to 3 hours, completed over one to two sessions. Questionnaires were mailed to parents to complete before the visit, with the option to finish it during the visit for collection by the speech pathologists.

Evaluation measures

The choice of child outcomes to be measured was motivated by the concept of “school readiness” (McLaughlin et al. 1995). In line with population studies in the USA (Berlin et al. 2003; Fulgini et al. 2003) and in Australia (Reilly et al. 2009; Reilly et al. 2010), the present study has focused on measuring outcomes relating to social skills development, language, speech production, and functional performance in everyday life using a combination of direct assessments administered to the child and report tools based on observations of parents and teachers. Table 2 shows the standardized measures used in the study for assessing children at 3 years of age.

Table 2.

Standardized measures used for assessing children.

| Construct | Measure | Abbreviation | Evaluation method |

Scales used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language | Preschool Language Scale v.4 (Zimmerman et al, 2002) | PLS-4 | Direct administration to child | Auditory comprehension; Expressive communication |

| Language | Child Development Inventory (Ireton, 2005) | CDI | Parent-report | Language comprehension; Expressive language |

| Receptive vocabulary | Peabody Picture vocabulary test (Dunn & Dunn, 2007) | PPVT | Direct administration to child | Total score |

| Speech production | Diagnostic Evaluation of Articulation and Phonology (Dodd & Crosbie, 2002) | DEAP | Direct administration to child | Consonant correct; Vowel correct |

| Psycho-social development | Child Development Inventory (Ireton, 1992) | CDI | Parent-report | Social |

| Functional performance in real life | Parents’ Evaluation of Aural/Oral performance of children (Ching & Hill, 2007) | PEACH | Parent-report | Total score |

| Teachers’ Evaluation of Aural/Oral performance of children (Ching et al. 2008). | TEACH | Teacher-report | Total score |

Three measures of spoken English were administered directly to children. The Pre-school Language Scale 4th ed. (PLS-4, Zimmerman et al. 2002) was used to measure receptive and expressive spoken English. It is a norm-referenced test for ages birth to 6 years 11 months, with two core subscales (Auditory Comprehension and Expressive Communication). The test has excellent test-retest reliability, and has been used extensively in research examining language development of young children from different home environments, children with identified medical conditions, children with hearing loss, and children participating in a variety of intervention programs (e.g. Zimmerman & Castilleja 2005; Moeller et al. 2010). Receptive vocabulary was assessed using the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, 4th ed. (PPVT-4, Dunn & Dunn 2007). It is a widely used test for ages 2.5 yrs to 90+years, with excellent validity and reliability. In test administration, the examiner presented a stimulus word orally, and the child was required to point to one of four pages that represented the word. The test gives an overall score, and has been used extensively for assessing children with hearing impairment (e.g. Fitzpatrick et al. 2011; Moeller et al. 2010). Speech production was assessed using the Phonology Assessment subtest of the Diagnostic Evaluation of Articulation and Phonology (DEAP, Dodd et al. 2002). The test was designed to assess production of vowels and consonants in single words and to examine phonological processes for children between 3 years and 6 years 11 months. The examiner presented pictures to the child to elicit oral production of words. These were transcribed and the number of vowels and consonants correctly produced were scored. The DEAP gives a vowel score and a consonant score. Direct assessments were video-recorded, and randomly-selected samples constituting at least 10 percent of the total were subjected to a second, independent scoring. The inter-observer reliability was 97 percent.

In addition, we used measures that relied on written reports. The Child Development Inventory (CDI, Ireton 2005) was used to measure language and psychosocial development of children. This inventory was designed for children between 15 months and 6 years of age, and has been used widely for assessing children with hearing impairment and those with additional needs (e.g. Yoshinaga-Itano 2003). Parents were given a booklet that contained 270 statements, and were asked to indicate those statements that describe their child’s behavior by marking YES or NO on an answer sheet. The items were grouped to form developmental scales. Scoring was done by counting the number of YES responses for each scale. For each sub-scale, the scores were converted into developmental ages using the published test manual. Quotients were calculated by dividing the child’s developmental age by chronological age, expressed as a percentage. To assess children’s auditory functional performance in real-world environments, the Parents’ Evaluation of Aural/Oral performance of Children (PEACH, Ching & Hill 2007) was used. The scale comprised 11 items, pertaining to performance in quiet and noisy situations in real life. Parents were asked to observe their child in different environments and note down specific examples of their child’s auditory behavior and functional performance in answer to each item. They were also asked to rate, on a 0 to 4 scale, the proportion of time their children demonstrated the auditory behavior. Ratings for all items were combined to give a total score. The scale has been shown to be appropriate for evaluating performance of young children with hearing impairment with good validity and reliability, and Australian norms are available (Ching & Hill 2007; Ching et al. 2008; Golding et al. 2007). Adapted from the PEACH scale for use by teachers, the Teachers’ Evaluation of Aural/oral performance of Children (TEACH) has 9 items (5 for quiet situations and 4 for noisy situations) for examining children’s auditory behaviors in early education settings. The scale has good validity and reliability and has been used for evaluating amplification for young children (Ching et al. 2008). Early education teachers named by the parents were sent the TEACH questionnaire prior to a child’s evaluation, and were asked to observe the child’s auditory behavior in a range of situations in the early education setting and provide a rating for each item. The teachers’ ratings were collected either at the time of the child’s evaluation, or by phone at a time convenient to the teacher. Ratings for all items were summed to give a total score.

All assessments were completed using standard methods. Administration was slightly modified in some cases to cater for children’s abilities. Children with poor hand control, for example, completed the PLS-4 using large blocks; and children with vision impairment were allowed additional time to look at pictures. Where a child used a combined oral and manual mode of communication, the PLS-4 and the DEAP were administered in the same communication mode by a speech pathologist/ sign-language interpreter, and the PPVT-4 was not administered. Tests of spoken English (PLS-4, DEAP, PPVT-4) were not administered to children whose parents reported that the children had not commenced learning English, or children who did not use spoken English for more than 50% of time at home (as reported by parents). For measures of spoken English that required parent/caregiver input (early items of PLS-4, Expressive Language and Language Comprehension of the CDI), the measures were not completed with parent/caregivers if they were not competent in English to be able to make judgments about their child’s oral English abilities. For measures of functional abilities of children, written questionnaires including the CDI (excluding the Expressive Language and Language Comprehension subscale items) and the PEACH were translated into the preferred language of parents/caregivers for completion.

We used published norms to derive standard scores or quotients from raw scores. Where appropriate normative data were not already available, the research team used the same measurement methods to assess 48 normal-hearing children who were matched with the research sample in terms of the distribution of age, gender and socio-economic status. The normal-hearing children were recruited from daycare centers and kindergartens in metropolitan and regional areas in the three Australian states of NSW, VIC and QLD. For the PLS-4, the DEAP and the PEACH scales, group mean scores and standard deviations in children with normal hearing were used to derive z scores for children with hearing impairment. For the PPVT-4 and the CDI, published norms were used to derive standardized scores and quotients respectively.

Information about hearing and hearing devices

We obtained information about child participants from clinical records held at AH, with permission from parents/caregivers. The collected information included gender, presence or absence of auditory neuropathy, age at diagnosis, age at first fitting of hearing aids, prescription used for fitting, measures of hearing aids, and hearing devices used (hearing aids and/or cochlear implants). For children with cochlear implants, information about age at switch-on, implant type, speech processor and coding strategy were collected from records held at cochlear implant service centers.

Children who enrolled prior to initial amplification were randomly assigned to being fitted using either the National Acoustic Laboratories’ procedure for non-linear hearing aids, version 1 (NAL) Prescription (Byrne et al. 2001) or the Desired Sensation Level (DSL) Prescription, version 4.0 (Seewald et al. 1997). Children who enrolled after initial fitting were fitted with the NAL prescription by AH audiologists. In accordance with the national protocol (King 2010, hearing-aid fitting for all children involved the use of real-ear-to-coupler differences (RECD) to derive custom prescriptive targets, and the measurement of hearing aids in an HA2-2cc coupler to verify that targets were matched to within 5 dB at 4 of the 5 octave frequencies between 0.25 and 4 kHz.

Children with auditory neuropathy were fitted with hearing aids according to the AH protocol for infants with auditory neuropathy (King et al. 2005). The audiogram for fitting was estimated on the basis of the minimum response levels obtained during behavioral observation audiometry (BOA) assessments. Measurements of auditory evoked cortical responses using speech sounds as stimuli were used when required.

Ongoing services for assessment of hearing and selection and verification of hearing aids for all children using standardized clinical methods are provided by the AH national service provision network. These include adjustments of hearing aids when changes in hearing thresholds occur and when updated versions of prescriptive procedures become available. A team of research audiologists monitored changes in measured hearing thresholds and supported hearing-aid fitting of participants via the service network.

Demographic information

Parents or caregivers reported information about their family and their child by completing custom-designed questionnaires. The solicited information comprised maternal/paternal ethnicity, their hearing status, level of formal education, and employment status. In addition, parents/caregivers reported on the birthweight of their child, any other disabilities experienced by their child, the communication mode they use with their child at home, language use at home, age at which their child enrolled in early educational programs, the communication mode used in those programs with their child, hours of intervention/week received in each program with entry and exit dates (where applicable), and whether their child has changed educational programs over the first 3 years of life. Parents also reported on their child’s use of hearing devices. The postcode of residence was used for assignment of socio-economic level using the census-based Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA, Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006) Index for Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD) (representing attributes such as income, educational attainment, employment, occupation, housing cost, household over/undercrowding, internet access) in Australia. The IRSAD scores are standardized for the Australian population to a mean of 1000 ± SD of 100, with the higher scores indicating relatively greater advantage and lack of disadvantage. Maternal education was specified in terms of a 3-point scale: less than or equal to 12 years of school attendance, diploma or certificate, and university qualification. The mode of communication used with the child at home and during educational intervention was categorized into aural/oral only, oral and manual combined, and sign/manual only. For educational programs named by parents/ caregivers, information about type of program and communication mode during educational intervention was collected from service providers.

Statistical analysis

Multiple regression analysis was used to investigate the effect of predictor variables on outcomes, after controlling for the effects of other variables.

The primary outcome measures were receptive and expressive language (three receptive and two expressive scores; including PLS-4 Auditory Comprehension score, CDI Language Comprehension score, PPVT score, PLS-4 Expressive Communication score, CDI Expressive Language score), speech production (DEAP vowel score and consonant score), social development (CDI Social subscale score), and auditory functional performance (PEACH score and TEACH score). We hypothesized that the abilities assessed by the individual outcomes measures are all affected by the same reduced ability to understand speech and language as a consequence of the hearing impairment and as modified by the predictors, though not necessarily all to the same degree. Therefore we performed a factor analysis to derive the underlying factor(s). Using the global factor score as the dependent variable in the regression has three main advantages. Firstly, the effects of measurement errors and other random variations in individual test scores were reduced in using the underlying global outcomes factor score that was calculated from the weighted average of the multiple measured scores. Secondly, the global outcomes factor score allowed a larger sample size than if an individual test score were used as a dependent variable because each subject needed a minimum of two individual test scores to have a global score. The use of multiple imputations corrected (in theory) for the uncertainty in the missing scores for some tests. Thirdly, the use of a global factor score, rather than a separate analysis for each of the many individual measures avoided the need to establish a stricter Type 1 error criterion (i.e. alpha level) due to the multiple regressions that would have been carried out. The current approach maximized statistical power in the analysis and generated more reliable estimates than if an individual test score were used in the regression model.

The predictors were 15 variables, 10 of which were categorical variables and 5 were continuous variables. Categorical variables included gender, device (hearing aids or cochlear implants), presence or absence of additional disability, presence or absence of auditory neuropathy, communication mode during educational intervention (no intervention, oral mode, other [including oral and manual combined mode as well as manual only]), change in communication mode during educational intervention (not attending or no change, changed from oral mode to other, changed from other to oral mode), communication mode at home (oral mode or other), language used at home (English or other), maternal education (≤ 12 years of schooling, certificate or diploma, university), and hearing-aid prescription (DSL or NAL). The continuous variables included age at first fitting of hearing aids (log transformed, represented non-linearly), age at switch-on of first cochlear implant (log transformed, quadratic), birth weight (represented non-linearly), four-frequency-average hearing loss (4FA HL, average of hearing threshold levels at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 KHz; represented non-linearly) in the better ear, and socio-economic status in terms of IRSAD scores. Except for IRSAD, all continuous variables were represented by splines to avoid assuming a linear relationship with the dependent variable. In order to allow each of hearing level and age at first fitting to have different effects in the group of children with hearing aids and the group with cochlear implants, interaction terms were included between device type and 4FA HL; between device type and age at first fitting; and between presence/absence of additional disabilities and age at first fitting.

The multiple imputation method (Rubin 1987 was applied to handle missing values in predictor and outcomes variables. In the regression analysis, a favorable ratio of data points to unknown coefficients was maintained at more than 10:1, allowing for an adequate estimation of the effects of 15 raw predictors, some of which were non-linearly transformed, together with interaction terms. We used two-tailed tests for all analyses and set statistical significance at p < 0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using Statistica (StatSoft Inc 2005) and R (R Development Core Team 2011) with the additional R packages ggplot2 (Wickham 2010) and rms (Harrell 2011).

RESULTS

A total of 451 children participated in the study. Of the 1020 infants that met inclusion criteria, 536 (53%) families gave consent for participation. Subsequently, 79 children were lost to follow-up and 6 were deceased. Participants were similar to nonparticipants with respect to age, sex, and severity of hearing loss. In terms of socio-economic status, the participants and non-participants have comparable means (1025.7 vs 1038.7) and interquartile ranges (962.1 vs 967.7, and 1087.7 vs 1114.2, respectively for 25th and 75th centiles). Table 3 summarizes the participants’ characteristics, including those relating to the child, family, and educational intervention.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of all participants (n = 451); and those included in the derivation of global outcomes factor score (n = 356).

| Characteristics | n = 451 | n = 356 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Male) | No.(%) | 247 (55%) | 190 (53%) |

| Age of diagnosis (months) | Mean (SD) | 6.0 (8.2) | 5.1 (7.3) |

| Median | 2.1 | 1.9 | |

| 25th to 75th percentile | 1.0 to 6.4 | 1.0 to 5.0 | |

| Not reported – no. | 3 | 2 | |

| Age of fitting (months) | Mean (SD) | 8.9 (8.8) | 7.9 (8.1) |

| Median | 4.9 | 4.2 | |

| 25th to 75th percentile | 2.5 to 12.9 | 2.4 to 10.8 | |

| Age of implantation (months) | Mean (SD) | 17.7 (9.0) | 21.5 (15.3) |

| Median | 15.0 | 16.7 | |

| 25th to 75th percentile | 9.9 to 24.1 | 10.3 to 26.5 | |

| Birthweight (gms) | Mean (SD) | 2998.9 (961.9) | 2992.7 (978.4) |

| Median | 3180 | 3200 | |

| 25th to 75th percentile | 2590 to 3640 | 2580 to 3650 | |

| Not reported – no. | 59 | 44 | |

| Device: cochlear implant | Unilateral cochlear implant – no.(%) | 13 (3) | 10 (3) |

| Cochlear implant and hearing aid in contralateral ears – no.(%) | 61 (14) | 46 (13) | |

| Bilateral cochlear implants – no.(%) | 60 (13) | 50 (14) | |

| Device: Hearing aid | Unilateral bone conductor – no.(%) | 11 (2) | 9 (3) |

| Unilateral – no. (%) | 11(2) | 11 (3) | |

| Bilateral – no. (%) | 289 (64) | 230 (65) | |

| Device: none | No. (%) | 6 (1) | 0 |

| Presence of Additional disabilities | No. (%) | 107 (24) | 96 (26) |

| Not reported | 78 (17) | 41 (11) | |

| Presence of auditory neuropathy | No. (%) | 44 (10) | 36 (10) |

| Severity of hearing loss in the better ear, averaged across 0.5 to 4k Hz – no. (%) | Mild (20 – 40 dB HL) | 86 (19) | 66 (19) |

| Moderate (41 – 60 dB HL) | 149 (33) | 116 (33) | |

| Severe (61 – 80 dB HL) | 71 (18) | 64 (18) | |

| Profound (>80 dB HL) | 145 (32) | 107 (30) | |

| Communication mode at home – no. (%) | Aural/oral only | 303 (67) | 241 (68) |

| Oral and sign | 101 (22) | 80 (22) | |

| Not reported | 47 (10) | 35 (10) | |

| Language used at home – no. (%) | English | 356 (79) | 305 (86) |

| Other | 23 (5) | 15 (4) | |

| Not reported | 72 (16) | 36 (10) | |

| Maternal education – no. (%) | School | 138 (31) | 104 (29) |

| Diploma or certificate | 101 (22) | 79 (22) | |

| University | 158 (35) | 132 (37) | |

| Not reported | 54 (12) | 41 (12) | |

| Socio-economic status (IRSAD Decile) | Mean (SD) | 7.1 (2.5) | 7.1 (2.4) |

| Median | 7.0 | 7.0 | |

| 25th to 75th percentile | 6 to 9 | 6 to 9 | |

| Age at enrolment in early education (months) | Mean (SD) | 10.8 (9.1) | 9.9 (9.0) |

| Median | 8 | 7 | |

| 25th to 75th percentile | 4 to 16 | 4 to 13 | |

| Not reported | 41 | 27 | |

| Amount of educational intervention (no. of hours) | Mean (SD) | 139 (114.7) | 145 (114.7) |

| Median | 120 | 124 | |

| 25th to 75th percentile | 64 to 192 | 66 to 196 | |

| Not reported | 22 | 20 | |

| Communication mode in early education – No. (%) | Aural/oral only | 301 (67) | 240 (67) |

| Oral and sign | 98 (22) | 71 (20) | |

| Not reported | 43 (10) | 36 (10) | |

| Not attending | 9 (2) | 9 (3) | |

Child characteristics

The cohort comprised 451 children (204 girls and 247 boys), of whom 255 (57%) were fitted with hearing aids before 6 months of age. Of the 306 children who were referred under UNHS, the median age of hearing-aid fitting was 3.3 months (mean =5.87, SD = 5.9, interquartile range: 2.2 to 6.5). For the entire cohort, hearing aids were fitted on average within 3 months of diagnosis (mean = 2.9, median = 1.4, SD = 4.3, interquartile range: 0.9 to 2.8), and enrolment in educational intervention occurred within 5 months of diagnosis (mean = 4.8, SD = 8.9, median = 3.2, interquartile range: 0.7 to 9.3). Table 4 shows the hearing devices used by participants at 3 years of age. Of the 134 children who use cochlear implants, 46 (34%) received their first implant before 12 months of age. All children use the Nucleus device with either the CI512 or the Freedom implant system together with either the Contour 24 or the Contour Advance 24 array. Based on parent reports, majority (85%) of children with hearing aids and all but one child with cochlear implants used their hearing devices for more than 75% of their waking hours.

Table 4.

Devices of participants.

| No Cochlear implant |

One cochlear implant |

Two cochlear implants |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| No hearing aid | 6 | 13 | 60 |

| One hearing aid | 22 | 61 | - |

| Two hearing aids | 289 | - | - |

In the present cohort, 44 children were identified with auditory neuropathy (bilateral), of whom 27 (61%) were fitted with hearing aids before 6 months of age, and the remaining between 6 and 20 months. Thirteen of the children with auditory neuropathy have additional disabilities, 6 of whom have more than one additional disability. Six children were diagnosed with visual impairment, 7 with cerebral palsy and 5 with other medical conditions. By 3 years of age, 26 of the 44 children used hearing aids, and the remaining children used cochlear implants (8 bilaterally, 4 unilaterally and the remaining used a cochlear implant and a hearing aid in opposite ears).

The present cohort also included 107 children diagnosed with additional disabilities, 44 (41%) of whom have more than one additional disability. Twenty-five children (23%) were diagnosed with cerebral palsy, 36 (34%) with vision impairment, 12 with autism spectrum disorder (11%) and 60 (56%) with other medical conditions. At 3 years of age, hearing aids were used by 74 (69%) children, and cochlear implants were used by 33 (31%) children.

Family characteristics

The communication mode used with children at home was reported to be aural/oral only for 67% of children; manual only (Australian sign language or Auslan) for 1%; and a combination of oral and manual methods for 22% of children. Data were missing for 10% of the cohort. The group that used a communication mode that combined oral and manual methods included children who used manually coded English (signed English), or some other augmentative alternative communication systems that use gestures, symbols, or signs to support speech (Walker & Armfield 1981; Beukelman & Mirenda 1998). For purposes of subsequent analysis, the 3 children that were reported to use sign only were grouped together with children that were reported to use a combination of oral and manual methods. The language-learning environment at home was reported to be English, with or without other spoken languages, for 79% of children. The spoken languages reported by the remaining families included African, Arabic, Asian, and European languages.

Educational intervention characteristics

Information relating to age at enrolment and communication mode in educational intervention was available for 429 children, of whom 26 children did not access any educational intervention or support service. The communication mode used during educational intervention was predominantly aural/oral for 301 children (67%), manual only for 7 children (2%), and the remaining 91 children (20%) used a combined oral and manual mode of communication. Between first enrolment in educational intervention and 3 years of age, parents of 50 children (11%) reported a change in communication mode during educational intervention. Of children who experienced changes, 27 changed from aural/oral only to a combination of oral and manual communication, and 17 changed from a combined mode to an aural/oral only mode. Two changed from a manual only mode to a combined mode and four changed in the opposite direction. The communication mode used during educational intervention and the occurrence of a change in communication mode in educational intervention were both used as predictors in subsequent regression analyses.

Relations among child, family and educational intervention variables

Table 5 shows the correlations among child, family, and educational intervention characteristics. Spearman rank-order correlation analysis revealed that on average, age at diagnosis, age at fitting, and age at enrolment in educational intervention were significantly correlated (p < 0.001). The positive correlations suggest that children whose hearing loss was diagnosed early also received earlier auditory intervention and earlier educational intervention. Due to the high correlations among these variables, only one could validly be used as a predictor in the multiple regression analysis. For this purpose, age at first fitting of hearing aids was selected for better accuracy because it was directly retrieved from the client database of the national hearing service provider, whereas the information about both diagnosis and enrolment in educational intervention relied on subjective reports from parents and teachers.

Table 5.

Spearman rank order correlation coefficients among child, family and intervention characteristics of participants. The age at diagnosis, age at fitting and age enrolled at educational intervention (EI) are in months. Hearing loss is represented by four-frequency-average hearing level (4FA HL, average of thresholds at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz in the better ear). Maternal education is depicted by a three-category variable, with 1 = university, 2 = diploma or certificate and 3 = less than or equal to 12 years of schooling). Socio-economic status is represented by the Index of Relative Social Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD) in deciles. Communication mode during educational intervention (CM_EI) is a three-category variable, with 1 = oral only, 2 = combined oral and manual methods, 3 = manual only). The same categories were used in specifying communication mode at home (CM_Home).

| Age at diagnosis |

Age at fitting |

Age at EI | 4FA HL | Maternal education |

IRSAD | CM_ EI |

CM_ Home |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | - | |||||||

| Age at fitting | 0.78*** p < 0.001 |

- | ||||||

| Age at EI | 0.55*** p <0.001 |

0.63*** p <0.001 |

- | |||||

| 4FA HL | −0.13** p = 0.006 |

−0.25*** p <0.001 |

−0.19** p <0.001 |

- | ||||

| Maternal education | 0.11* p = 0.02 |

0.09 | 0.13* p = 0.01 |

0.01 | - | |||

| IRSAD | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.09 | −0.04 | −0.31*** p < 0.001 |

- | ||

| CM_EI | 0.10 p = 0.05 |

0.05 | 0.004 | 0.13** p = 0.008 |

0.09 P = 0.06 |

−0.18*** p < 0.001 |

- | |

| CM_Home | 0.08 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.20*** p <0.001 |

0.08 | −0.13* * p = 0.006 |

0.65*** p < 0.001 |

- |

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p <0.001

Higher levels of maternal education were significantly associated with higher socio-economic status (p < 0.001), earlier age at diagnosis (p < 0.02), and earlier enrolment of children in educational intervention (p = 0.01). Communication modes at home and during educational intervention were correlated (p < 0.001), suggesting that the same communication mode was used with children in the two settings. The significant correlations between severity of hearing loss and communication modes used at home (p < 0.001) and during educational intervention (p < 0.01) indicated that greater severity of hearing loss was associated with increased use of combined oral and manual modes of communication in both settings. Severity of hearing loss was negatively related with both age at hearing-aid fitting (p < 0.001) and age at enrolment in educational intervention (p < 0.001), suggesting that children with more severe hearing losses were fitted earlier and attended educational intervention earlier.

Predicting outcomes of children

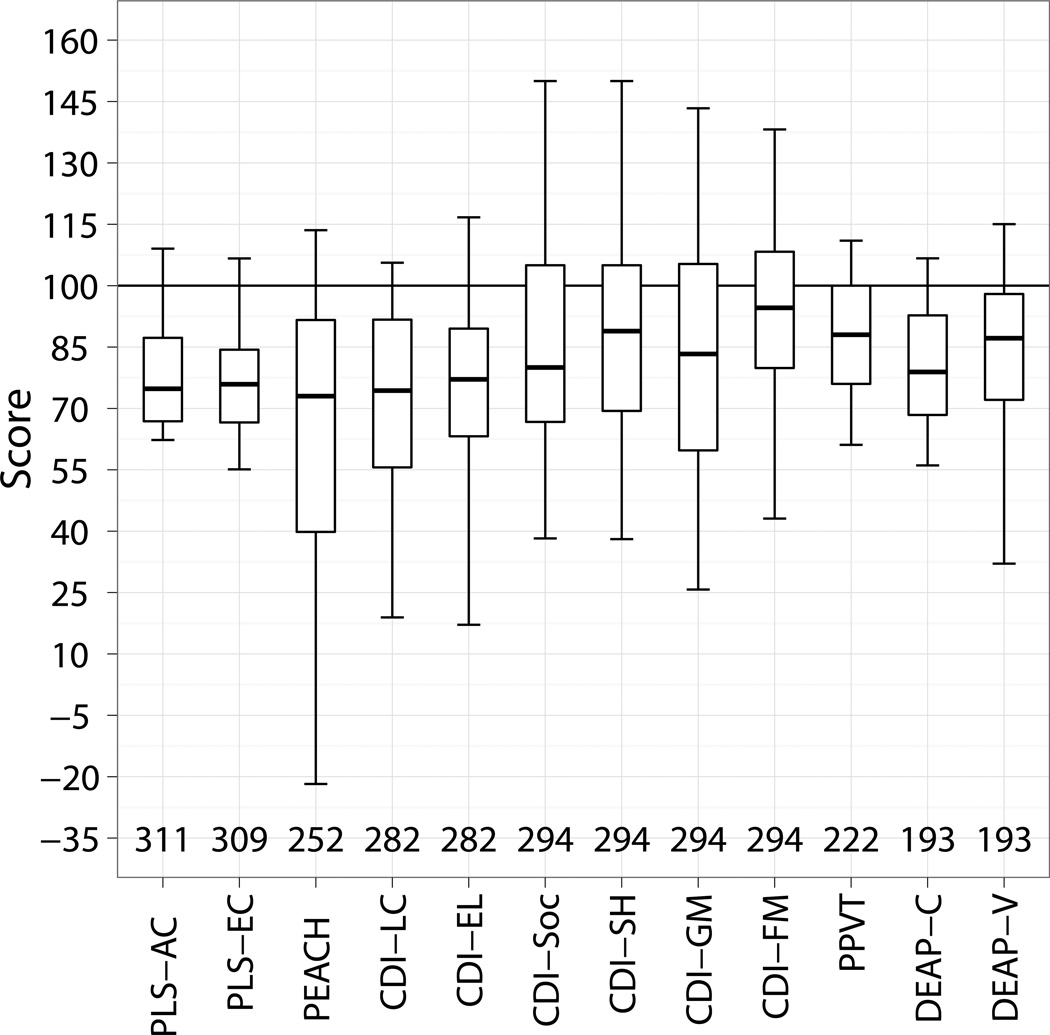

Figure 1 shows the standardized scores for individual test measures. On average, children’s performance in expressive and receptive language, speech production, social and auditory functional abilities were at or below one standard deviation (SD) of the normative mean. Table 6 shows the count of participant numbers for individual tests, in relation to characteristics of the sample. Assessment data were missing for some participants as a result of their being unable to cope with the demands of directly administered formal tests, or they were not learning or using oral English as reported by parents (see Methods). On other occasions, participants were unavailable for testing, or assessments were attempted but not completed, or parents could not report on their child’s oral English abilities, or questionnaires were not returned.

Figure 1.

Standardised scores (normative mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15) for a range of test measures administered to children. The test measures include the Pre-school Language Scale - Auditory Comprehension (PLS-AC), Pre-school Language Scale -Expressive Communication (PLS-EC), Parents’ Evaluation of Aural/Oral Performance of Children (PEACH), Child Development Inventory Language Comprehension (CDI-LC), Child Development Inventory Expressive Language (CDI-EL), Child Development Inventory Social scale (CDI-Soc), Child Development Inventory Self-Help scale (CDI-SH), Child Development Inventory Gross Motor scale (CDI-GM), Child Development Inventory Fine Motor scale (CDI-FM), Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT), Diagnostic Evaluation of Articulation and Phonology - Consonant correct (DEAP-C) and Diagnostic Evaluation of Articulation and Phonology - Vowel correct (DEAP-V). The number of children that contributed to each test is shown. The box indicates the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles and the bars depict the 5th and 95th percentiles.

Table 6.

Number of participants with different characteristics from whom data were collected for each assessment instrument: Pre-school Language Scale – Auditory Comprehension scale (PLS-AC), Preschool Language Scale – Expressive Communication (PLS-EC), Parents Evaluation of Aural/oral performance of Children (PEACH), Teachers’ Evaluation of Aural/oral performance of children (TEACH), Child Development Inventory – Language Comprehension scale (CDI-LC), Child Development Inventory – Expressive Language (CDI-EL), Child Development Inventory – Social scale (CDI – Soc), Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT), Diagnostic Evaluation of Articulation and Phonology – consonants (DEAP-C), and Diagnostic Evaluation of Articulation and Phonology (DEAP-V). A total of 356 participants were included.

| Variable | Value | Overall | PLS- AC |

PLS- EC |

PEA CH |

TEA CH |

CDI- LC |

CDI- EL |

CDI- Soc |

PP VT |

DEA P-C |

DEA P-V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additional disability | No | 219 | 198 | 196 | 167 | 138 | 180 | 180 | 187 | 165 | 149 | 149 |

| Yes | 96 | 80 | 80 | 62 | 60 | 76 | 76 | 79 | 39 | 30 | 30 | |

| Missing | 41 | 33 | 33 | 19 | 18 | 26 | 26 | 28 | 17 | 14 | 14 | |

| Gender | Male | 190 | 166 | 166 | 133 | 122 | 151 | 151 | 156 | 112 | 94 | 94 |

| Female | 165 | 145 | 143 | 115 | 94 | 131 | 131 | 138 | 109 | 98 | 98 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Maternal education | School | 104 | 87 | 87 | 67 | 64 | 82 | 82 | 89 | 57 | 42 | 42 |

| Diploma/ certificate | 79 | 73 | 73 | 60 | 50 | 68 | 68 | 68 | 49 | 42 | 42 | |

| University | 132 | 118 | 116 | 99 | 84 | 109 | 109 | 113 | 96 | 91 | 91 | |

| Missing | 41 | 33 | 33 | 22 | 18 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 19 | 18 | 18 | |

| Auditory neuropathy | No | 320 | 284 | 282 | 222 | 196 | 255 | 255 | 265 | 199 | 177 | 177 |

| Yes | 36 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 20 | 27 | 27 | 29 | 22 | 16 | 16 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Device | HA only | 250 | 220 | 219 | 170 | 151 | 202 | 202 | 210 | 162 | 143 | 143 |

| CI | 106 | 91 | 90 | 78 | 65 | 80 | 80 | 84 | 59 | 50 | 50 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Prescription | NAL | 228 | 197 | 196 | 161 | 144 | 181 | 181 | 191 | 135 | 116 | 116 |

| DSL | 126 | 112 | 111 | 86 | 71 | 99 | 99 | 101 | 84 | 77 | 77 | |

| Missing | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Communication mode at home | Oral + sign | 80 | 69 | 69 | 52 | 54 | 68 | 68 | 69 | 28 | 24 | 24 |

| Oral only | 241 | 211 | 209 | 178 | 148 | 194 | 194 | 203 | 177 | 153 | 153 | |

| Missing | 35 | 31 | 31 | 18 | 14 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 16 | 16 | 16 | |

| Language at home | No spoken English | 15 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 5 |

| Includes English | 305 | 270 | 268 | 219 | 195 | 252 | 252 | 260 | 198 | 173 | 173 | |

| Missing | 36 | 32 | 32 | 17 | 13 | 21 | 21 | 23 | 16 | 15 | 15 | |

| Communication mode at early education | None | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Oral only | 240 | 214 | 213 | 178 | 151 | 197 | 197 | 202 | 171 | 153 | 153 | |

| Oral + sign | 71 | 59 | 59 | 44 | 49 | 58 | 58 | 60 | 25 | 19 | 19 | |

| Missing | 36 | 29 | 29 | 20 | 14 | 20 | 20 | 24 | 20 | 17 | 17 | |

| Change in early communication | None | 283 | 249 | 247 | 202 | 175 | 230 | 230 | 237 | 184 | 161 | 161 |

| Spoken to Other | 20 | 17 | 17 | 15 | 15 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 8 | 3 | 3 | |

| Other to Spoken | 17 | 16 | 16 | 11 | 12 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 9 | 12 | 12 | |

| Missing | 36 | 29 | 29 | 20 | 14 | 20 | 20 | 24 | 20 | 17 | 17 |

The factor analysis for deriving global outcomes factor scores included 356 children who had scores on at least two test instruments. The CDI fine motor, gross motor and self-help subscale scores were not included in this factor analysis. This decision was made on theoretical grounds after examining the content of the items for the subscales, and reasoning that the abilities they represent were less likely to be affected by hearing loss, and that their inclusion would therefore weaken the accuracy of the global factor. The CDI social subscale score was included in the factor analysis because the items for the subscale evaluated verbal and non-verbal interactions between the child and other individuals. As social interactions create the context for exercising language skills (Ireton, 2005), children’s ability to interact with others are intimately related to their language skills, both of which are affected by auditory input. Examination of the correlation matrix of the outcome measures confirmed that the correlations between these excluded measures and the measures included in the factor analysis were lower than those between the included measures. Using a least squares method, a single factor was extracted, as suggested by the “scree plot” and “eigenvalues greater than 1” guidelines. Table 7 gives the factor loadings showing the extent to which each measured outcomes contributed to the meaning of the derived factor, together with factor coefficients for each outcomes measure. A weighted sum of the PLS-4 Auditory Comprehension score, PLS-4 Expressive Communication score, PPVT score, DEAP consonant score, DEAP vowel score and the PEACH score was formed. The weights were proportional to the coefficients for obtaining the factor score from the individual test scores. Simple linear regression was performed with the weighted sum as the dependent variable and the factor score as the independent variable. Each child’s global outcomes score was then defined to be the fitted value corresponding to his/her factor score.

Table 7.

Factor loadings and coefficients.

| Outcome measure | Loading (Averaged across 10 imputations) |

Coefficients (Averaged across 10 imputations) |

|---|---|---|

| PLS-4 Auditory Comprehension | 0.85 | 0.128 |

| CDI Language Comprehension | 0.90 | 0.203 |

| PPVT Receptive vocabulary | 0.86 | 0.132 |

| PLS-4 Expressive Communication | 0.92 | 0.254 |

| CDI – Expressive Language | 0.87 | 0.144 |

| DEAP – Vowel production | 0.78 | 0.087 |

| DEAP – Consonant production | 0.73 | 0.070 |

| CDI – Social score | 0.63 | 0.044 |

| PEACH | 0.63 | 0.044 |

| TEACH | 0.53 | 0.032 |

Multiple regression analysis was conducted using the global outcomes score as the dependent variable to investigate the effect of age of initial hearing aid fitting on global outcomes, after controlling for the effects of 14 other predictors. Age of diagnosis and age of enrolment in educational intervention were not included as predictor variables in the regression model because these were highly correlated with one of the other variables (age of fitting) that was included as a predictor (see Table 5). We did not include use of hearing device as a predictor because the distribution was highly skewed towards high use, with about 85% of children with hearing aids and all but one child with cochlear implants reported to be using their hearing devices for more than 75% of waking hours. Also, we did not include hours of educational intervention as a predictor. Based on parent reports, we calculated the average number of hours per week of early education from program entry to age 3 years. Preliminary analysis indicated a negative relationship between hours of educational intervention and the global outcomes factor (r = −0.15, p = 0.003) – a consequence of children who had greater difficulties or comorbidities accessing more intervention hours from multiple educational agencies.

Table 8 shows the effect estimates and 95% confidence interval. For continuous predictors, the effect estimate is the predicted change in mean value of the global outcomes score when the predictor changes in value from the first to the third quartile with all other predictors held constant. For the two-category predictors, the effect estimate is the regression coefficient, and the change is the estimated difference in mean value of the global outcomes score for the stated category relative to the reference category. For communication mode during educational intervention, the reference category is no intervention. For communication mode change, the reference category is no change. For maternal education, the reference category is ≤12 years of schooling. None of the non-linear terms or interaction terms included in the model was significant at the 0.05 level. The whole model accounted for 40% of the total variation in the global outcomes factor score.

Table 8.

Multiple regression analysis of global outcomes factor scores with respect to predictors. The probability level (p) for each predictor refers to the multiple degree of freedom (df) test of all terms relating to that predictor. The estimated effect size and 95% confidence interval (CInt) for significant predictors are italicized.

| Predictor | df | p | Effect | CInt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additional disability (reference: absent) | 1 | < 0.001 | |||

| Present | −10.4 | (−14.4, −6.3) | |||

| Gender (reference: male) | 1 | 0.01 | |||

| Female | 4.0 | (0.8, 7.2) | |||

|

Maternal education (reference: ≤12 years school) |

2 | 0.01 | |||

| University | 6.3 | (2.1, 10.6) | |||

| Diploma | 4.2 | (−0.1, 8.4) | |||

| 4FA HL | 3 | 0.02 | |||

| HA group, from 38.8 to 61.3 dB HL |

−4.5a | (−7.9, −1.0) | |||

| CI group, from 85.0 to 110.0 dB HL |

0.1a | (−4.5, 4.8) | |||

| Age at switch-on of first cochlear implant | 2 | 0.04 | |||

| From 9.8 to 23.5 months | −8.1a | (−14.5, −1.8) | |||

| Age at fitting of first hearing aids | 3 | 0.59 | |||

| From 2.4 to 11.0 months, HA group |

−2.4a | (−5.8, 1.1) | |||

| CI group | −0.1a | (−6.1, 6.0) | |||

| Birthweight | 2 | 0.05 | |||

| From 2.6 to 3.6 kg | 2.3a | (−0.2, 4.8) | |||

| Auditory neuropathy (reference: absent) | 1 | 0.73 | |||

| Present | 1.0 | (−4.7, 6.8) | |||

| Device (reference: HA) | 3 | 0.73 | |||

| CI | −15.7 | (−50.6, 19.2) | |||

| Hearing aid prescription (reference: NAL) | 1 | 0.53 | |||

| DSL | 1.0 | (−2.1, 4.2) | |||

| Communication mode at home (reference: other) | 1 | 0.26 | |||

| Oral only | 3.0 | (−2.2, 8.1) | |||

| Language at home (reference: other) | 1 | 0.14 | |||

| Spoken English | 6.0 | (−2.1, 14.1) | |||

| Socio-economic status | 1 | 0.05 | |||

| IRSAD, from 968.9 to 1075.0 |

2.4a | (0.04, 4.8) | |||

| Communication mode during educational intervention (reference: no intervention) | 2 | 0.05 | |||

| Oral only | 4.5 | (−5.4, 14.4) | |||

| Other | −1.8 | (−12.4, 8.9) | |||

| Communication mode change in intervention (reference: no change) | 2 | 0.28 | |||

| Oral to other | −1.1 | (−9.2, 7.0) | |||

| Other to oral only | −5.3 | (−12.0, 1.4) | |||

change in the mean of the dependent variable associated with a change in the predictor from the value at the 25th percentile to 75th percentile. These predictors are continuous variables.

Five predictor variables were associated with the global outcomes factor scores at the 5% significance level. These included gender, additional disability, severity of hearing loss, maternal education and age at switch-on of cochlear implant. Girls had higher scores than boys (estimate: 4.02, 95% Confidence Interval [CInt]: 0.83 to 7.21).

Children who had disabilities in addition to hearing loss had lower scores than children who did not have other disabilities (estimate: −10.36; 95% CInt: −14.40 to −6.32). The presence of other disabilities explained 6.1% of the variance in scores, in addition to the variance explained by all other predictors in the model. If additional disability were the only predictor, it would explain 15.9% of the variance in scores. The interaction between age at amplification and presence/absence of additional disabilities was not significant (p = 0.74).

Relative to children whose mother completed ≤ 12 years of schooling, children whose mother completed diploma or certificate had higher scores (estimate: 4.17; 95% CInt: −0.08 to 8.42) and so did children whose mother completed university education (estimate: 6.33; 95% CInt: 2.07 to 10.60).

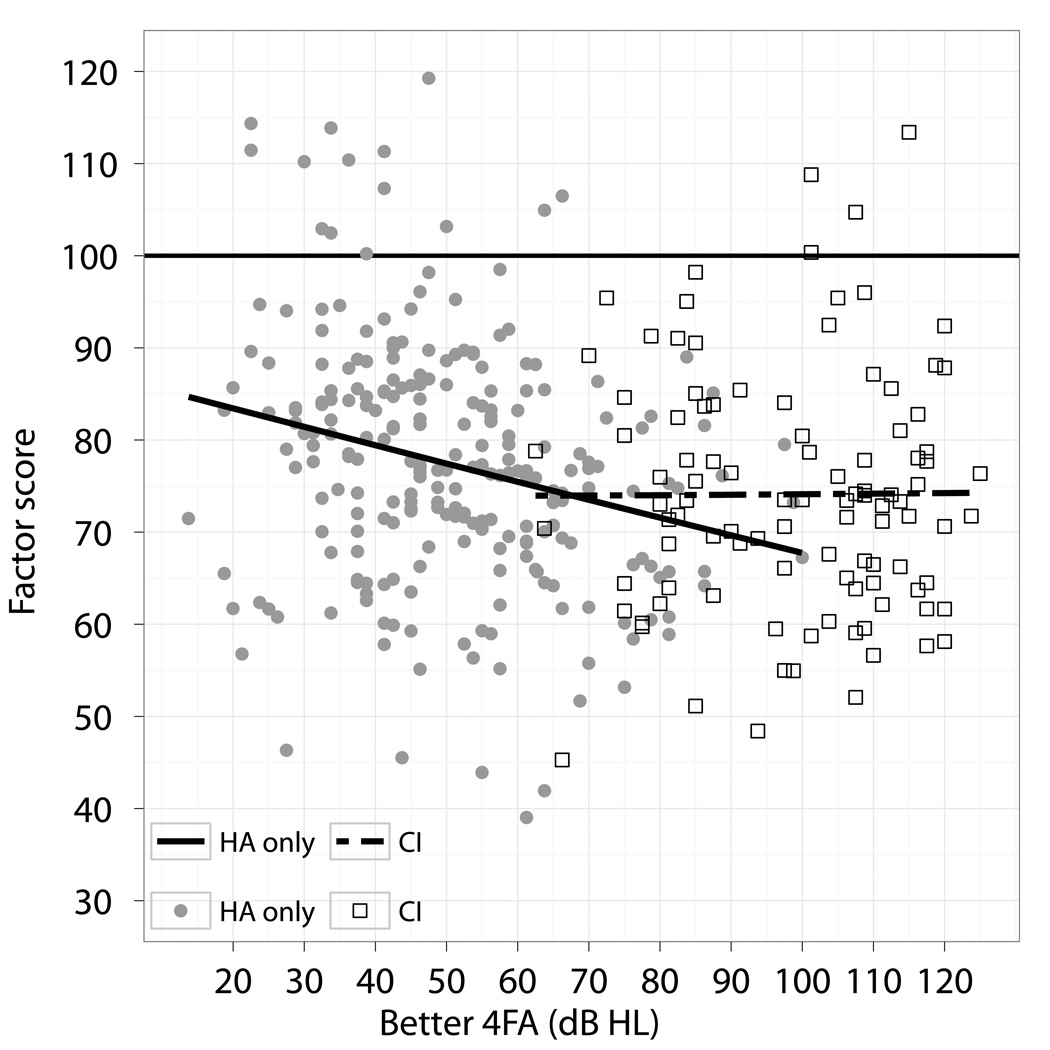

The present results also indicated that global outcomes factor scores decreased with increase in severity of hearing loss (p = 0.02). Figure 2 shows the variation in global outcomes factor score as a function of hearing loss in the better ear, adjusted for the effects of the other predictors. To make this adjustment, communication mode at early educational intervention was fixed at oral only, mode change was fixed at no change, maternal education was fixed at diploma or certificate, and other predictors were fixed at their mean values.

Figure 2.

Adjusted factor scores as a function of four-frequency average hearing loss (average of 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz) in the better ear (Better 4FA). Filled symbols show results of children with hearing aids and open symbols show results of children with cochlear implants at 3 years of age. The solid line represents the regression line for data of children with hearing aids, and the broken line represents the regression line for data of children with cochlear implants.

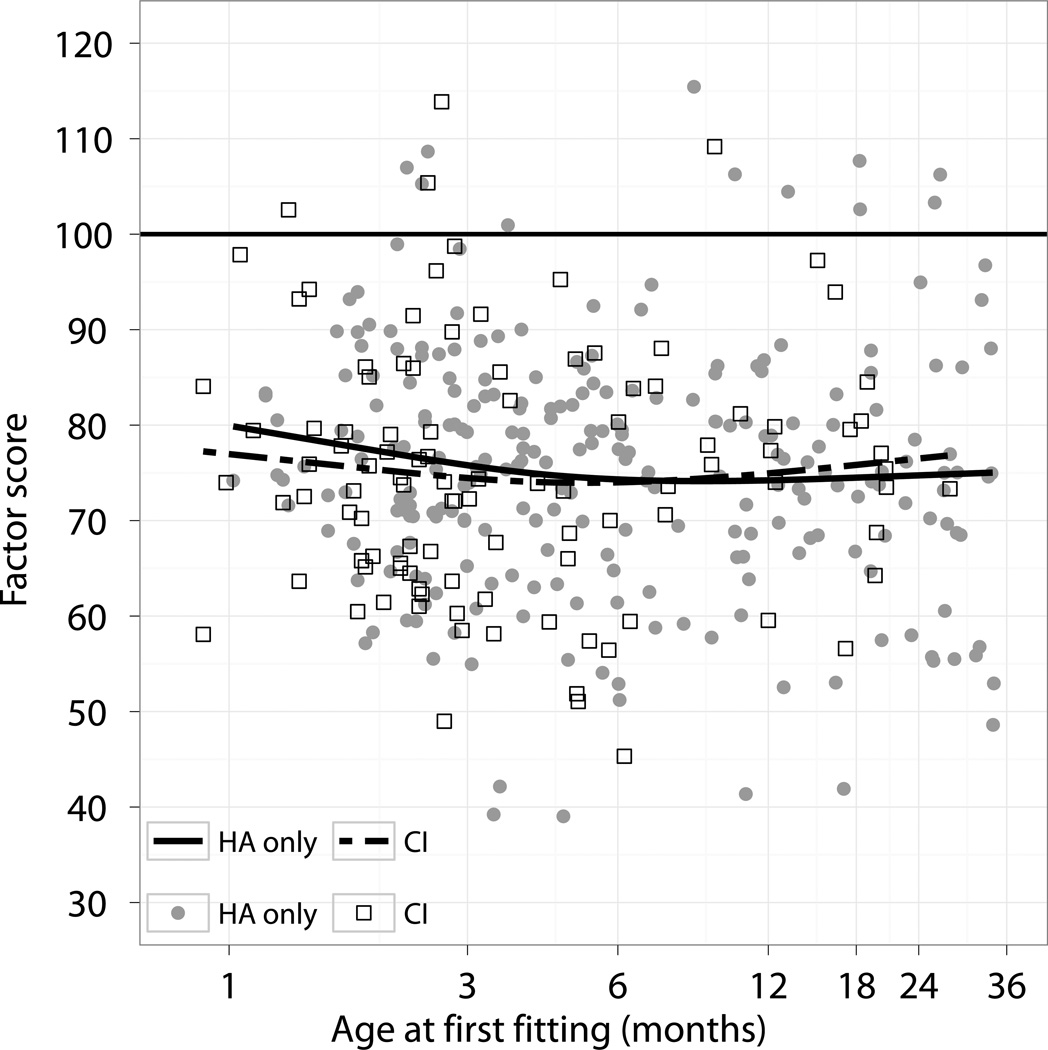

Figure 3 shows the relation between age at first-fitting of hearing aids and the adjusted global outcomes factor score, separately for children with hearing aids and those with cochlear implants. As Table 8 shows, a delay in age at hearing-aid fitting from 2.4 months to 11.0 months was associated with a degradation in global outcomes of 2.35 points (CInt: −5.83, 1.14). For children who used cochlear implants at 3 years of age, the age at first fitting of hearing aids had minimal effects on global outcomes (−0.09 points, CInt: −6.14, 5.96).

Figure 3.

Adjusted factor scores as a function of age at first fitting of hearing aids. Filled symbols show results of children with hearing aids, and open symbols show results of children with cochlear implants at 3 years of age. The solid line represents the regression curve for data of children with hearing aids, and the broken line represents the regression curve for data of children with cochlear implants.

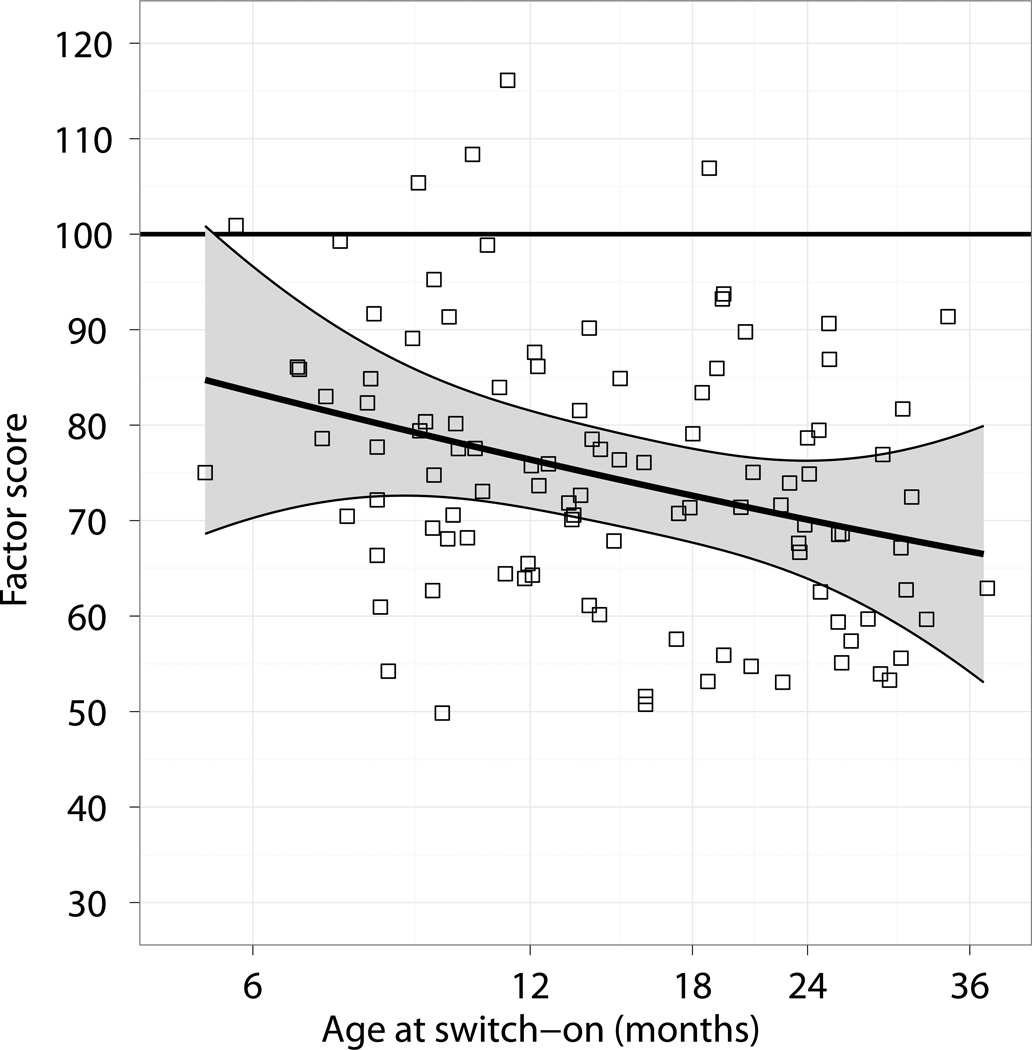

On the other hand, age at switch-on of first cochlear implant was significantly associated with global outcomes (p = 0.04), after controlling for the effects of other variables. Figure 4 shows the variation in adjusted factor score as a function of age at which the first (or only) cochlear implant was switched on. A delay in age at switch-on from 9.8 months to 23.5 months was associated with a degradation of 8.12 points in global outcomes (CInt: −14.45, −1.78).

Figure 4.

Adjusted factor scores as a function of age at which cochlear implants were switched on (Age at switch-on). Shaded area represents 95% confidence interval.

Discussion and Conclusion

This paper describes a contemporary cohort of children who were identified with hearing loss and received amplification before 3 years of age. All children have been provided with state-of-the-art technology in hearing devices using protocols consistently applied nationally in Australia.

The cohort in this study differs from those in previous studies in several ways. First, the present cohort differs from the samples reported in previous studies in the range of age of fitting spanned, but is more in keeping with current audiological practice in most countries. The median age of hearing-aid fitting for this cohort was 4.9 months with an interquartile range of 2.5 to 12.9 months. About 56% of children fitted with hearing aids before 6 months of age. Whereas previous controlled studies on UNHS examined the impact of confirming hearing loss by 9 months of age (Kennedy et al. 2006; Watkin et al. 2007; Worsfold et al. 2010) or hearing-aid fitting by 15 months of age (Korver et al. 2010), the present cohort included sufficient numbers of children fitted before and after 6 months of age to estimate reliably the efficacy of early amplification. On average, children received amplification from AH service centers within three months of diagnosis of hearing loss. Hearing services and technology provided to children were consistent across all service centers, with multi-channel non-linear hearing aids adjusted according to the NAL-NL1 or the DSL v.4.1 prescriptions, and real-ear measures being used to match prescriptive targets adequately according to national pediatric protocols (King 2010. Early diagnosis is a vital step towards the goal that children with hearing impairment achieve language and other outcomes commensurate with their normal-hearing peers (Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, 2007). Evidence on the early age of amplification for children referred from UNHS in the present cohort supports the benefit of newborn hearing screening for earlier access to useful hearing via hearing aids (Nelson et al. 2008).

Second, the present cohort included 134 children who use recent models of cochlear implants, with the median age of implantation at 15 months (interquartile range: 9.9 to 24.1). Previous population studies examining the effect of early detection and diagnosis on language outcomes included very few children with cochlear implants (n = 32, Korver et al. 2010; n = 16, Kennedy et al. 2006). Unlike studies on the effect of age at implantation on children’s outcomes in which early implantation referred to those implanted before 5 years of age (e.g., Geers et al. 2003) or 3 years (e.g., Connor et al. 2006; Kirk et al. 2002; Manrique et al. 2004; Nicholas et al. 2007; Svirsky et al. 2007), or 2 years (Svirsky et al. 2004) of age, or studies which included very small numbers of children implanted before 12 months of age (n = 11 in Dettman et al. 2007; n = 6 in Holt and Svirsky, 2008), the present cohort included 46 children (34%) who received their first cochlear implant before 12 months of age to allow the effect of early implantation during the first few years of life to be estimated reliably. In keeping with the benefit of newborn hearing screening for early audiological management, the early age of implantation for this cohort reflects early access to useful hearing via cochlear implants.

Third, children and families from non-English speaking background were not excluded from participation, this being a population-based study. Unlike published controlled studies in which children whose parents were not proficient in the native language were excluded (Korver et al. 2010; Niparko et al. 2010), all consenting families were included in the present cohort. Based on parent reports, 23 children (5%) did not use English as the primary language for communication at home. This study therefore allows an estimation of the effect of language used at home on children’s outcomes.

Fourth, children with additional disabilities were not excluded from participation, thereby allowing an examination of the extent to which outcomes were affected by the presence of additional disabilities. The present cohort comprised 107 children (24%) with additional disabilities, 74 of whom used hearing aids and 32 of whom used cochlear implants by 3 years of age. The proportion of children with disabilities in the present cohort is consistent with published reports on incidence of additional disabilities for children with hearing loss (Holden-Pitt et al. 1998). Of the published studies on hearing-impaired children with additional disabilities, a major focus has been the efficacy of cochlear implantation (e.g. Holt & Kirk, 2005; Berrettini et al. 2008; Meinzen-Derr et al. 2010; Beer et al. 2012), with very few studies on outcomes of children who use hearing aids (e.g. Bagatto et al. 2011). The present study quantifies the effect of the presence of additional disabilities on children’s outcomes at 3 years of age, including children who use hearing aids and those who use cochlear implants.

Despite the abovementioned differences between the present cohort and those investigated in previous published studies, the distribution of severity of hearing loss for the present cohort was comparable to that reported in previous controlled trials (Kennedy et al. 2006; Korver et al. 2010).

Predicting outcomes at 3 years

The regression model used to predict global outcomes for 356 children included 15 predictor variables that accounted for 40% of the total variance. Five predictors, including female gender, absence of additional disabilities, less severe hearing loss, higher maternal education and, for children with cochlear implants, the age at switch-on, were significantly associated with better developmental outcomes for children at 3 years of age.

Our study extends findings from previous studies that examined the efficacy of early detection and amplification by controlling for a wide range of demographic characteristics in a prospective comparison of outcomes of early- and late-identified children. Unlike studies in which access to auditory intervention (amplification) after diagnosis differed between regions with or without UNHS (Kennedy et al. 2006; Korver et al. 2010), this study took advantage of the uniform hearing service delivery system in Australia. Through the system, we enrolled sufficiently large numbers of children who received amplification before or after 6 months of age, and children who received cochlear implants before or after 12 months of age in order to reliably estimate the effect of early detection and device fitting on outcomes. We found that early hearing-aid fitting was not significantly associated with better outcomes at 3 years of age, after allowing for the effects of multiple putative factors. This lack of significant effects of early hearing-aid fitting on outcomes is consistent with that reported in previous population-based studies on expressive language of children at 8–12 years of age (Kennedy et al. 2006), expressive and receptive language of children at 3–5 years of age (Korver et al. 2010), and phrases understood by children at 12–16 months of age (Vohr et al. 2008). On the other hand, previous program-based studies reported an association between early enrolment in educational intervention and improved outcomes. Appuzzo and Yoshinaga-Itano (1995) reported retrospective data on 69 children divided into four age-of-identification groups, which revealed higher scores for expressive language at 40 months of age for infants diagnosed in the first 2 months of life than those diagnosed later. Yoshinaga-Itano et al. (1998) reported that children who enrolled in early education programs before 6 months of age had significantly better language scores than those who enrolled later. Both of these studies relied on un-blinded assessments using parental reports of convenience samples. Moeller (2000) reported on the receptive vocabulary of 100 children at 5 years of age, showing that on average, the group who enrolled in early education by 11 months of age had higher scores than those who enrolled between 11.1 and 54 months of age. It is important to note that the different findings may have arisen from potential sources of bias in the program-based studies, which lacked clear criteria for inclusion (including as participants only those who adhered to specific early intervention programs) and did not adjust for differences between baseline characteristics of comparison groups. These methodological limitations have been clearly identified in the USPSTF report (Thompson et al. 2001).

The current study demonstrated that the presence of additional disabilities was associated with a decrease of 10.4 global outcomes factor score points at 3 years of age. By including the presence of other disabilities as a predictor, it was possible to determine that about 6% of the below-normal performance was due to the presence of these other disabilities. The mean global outcomes factor score for the entire cohort was 74.6 (SD: 17.1). After adjusting for the effect of additional disability, the mean global factor score was 77.8. As the adjusted score is below 1 SD of the normative mean for the global factor score, it depicts the gap in development between children with hearing loss and those with normal hearing. Examination of the interaction between age at amplification and presence of additional disabilities revealed that there is insufficient evidence to conclude that age at amplification has different effects for children with or without other disabilities, after adjusting for the effects of other variables.

Even though the current study produced evidence that age of amplification was not a significant predictor of children’s outcomes at 3 years of age, the age at which the first cochlear implant was switched on was associated with outcomes at 5% significance level. This implies that UNHS and early auditory intervention are important for improving outcomes of children with severe or profound hearing loss, as early implantation would not have been possible without early detection. This study advances current knowledge by allowing for a range of baseline/demographic characteristics in quantifying the effect of age of implantation on the global outcomes achieved in a population of children. For children who required cochlear implantation for effective auditory stimulation, delaying commencement of electrical stimulation from 10 to 24 months was associated with a decrease of 8.1 factor score points (CInt: −14.5 to −1.8) for outcomes at 3 years of age. Given that the global factor score has been scaled so that a normal population should have a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15 points, a reduction of 8.1 points represents a more than one-half standard deviation shift in outcomes, which is a substantial decrement.

The weakness of the effect of early amplification for children with hearing aids may at first seem surprising. In principle, we would expect that age of fitting would have the greatest impact for those with the greatest loss. However, most of the children with losses greater than about 75 dB HL had cochlear implants when they were assessed around their third birthday (see Figure 2). Consequently, most of the children with hearing aids at the time of assessment had a mild or moderate loss. Perhaps the auditory stimulation these children received unaided was sufficient to enable development of the auditory cortex, such that when hearing aids were later provided, the children were able to make just as good use of the signals received as children who received their hearing aids earlier. Perhaps the children who received early amplification did not have educational intervention that targeted the development of auditory skills effectively to allow the advantage of early stimulation to be optimally realised. For the implanted children, there was also little effect of age at first hearing-aid fitting on the global factor score. Perhaps sufficient numbers of these children had so severe a loss that the hearing aids did not provide worthwhile auditory stimulation. Cortical development in response to sound would then not have commenced until the children received their implants, which is consistent with the strong effect found for age of implantation.