Abstract

Hsp70 is involved in immune responses against infectious pathogens, thermal, and osmotic stress. To understand the immune defense mechanisms of the mud crab Scylla paramamosain, genomic DNA, transcript level and antimicrobial activities of Hsp70 were analyzed. Genomic DNA sequence analysis revealed one intron in this gene. Furthermore, six SNPs were detected by direct sequencing from 30 samples in this study. Hsp70 mRNA was expressed in almost all tissues examined. By using the quantitative real-time PCR, the expression level of Hsp70 in hemocytes showed a clear time-dependent expression pattern during the 96 h after stimulated by Vibrio alginolyticus. Then, recombinant Hsp70 was obtained by using the bacterial expression system, but no obvious antimicrobial activity has been found for the protein in the antimicrobial tests. After osmotic stress, the expression of Hsp70 in hemocytes showed this gene was induced by the high salinity (30 ‰) for at least 96 h. Hsp70 mRNA expression in hemocytes was analyzed after thermal stress at 6 h, the highest and the lowest expression level of Hsp70 was observed at 36 and 15 °C, respectively. These results indicated that Hsp70 was inducible by bacterial, osmotic, and thermal stress, and therefore plays an important role, different from antibacterial peptide, in innate immune responses of S. paramamosain.

Keywords: Scylla paramamosain, Heat shock protein70 (Hsp70), mRNA expression, SNP, Different stress, Recombinant Hsp70

Introduction

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are a family of proteins that exist in all organisms ranging from prokaryotes to mammals and function mostly as molecular chaperons. HSPs are constitutively expressed under certain physiological conditions and take part in many important life activities, such as metabolism, growth, differentiation, programmed cell death, and fertilization (Ranford et al. 2000; Multhoff 2006; Coux and Mouquelar 2012). A wide variety of “stressful” stimuli, such as heavy metals, hyperthermia, anti-inflammatory drugs, and viral or bacterial infections, induce an increase in the intracellular synthesis of HSPs (Annamaria et al. 2004; Gehrmann et al. 2004; Tsan and Gao 2004a; Cui et al. 2010; Zhou 2010). As one of the most abundant and widely investigated families, the Hsp70 family is composed of cytosolic Hsp70 including the inducible Hsp70 and the cognate Hsc70, glucose-regulated protein 78 (Grp78), and mitochondrion Hsp75 (Kregel 2002). To our knowledge, the inducible Hsp70 and cognate Hsc70 are two closely related cytosolic forms. Compared to Hsc70 constitutively expressed under normal conditions (Park et al. 2001), Hsp70 is inducible and involved not only in protein folding and cytoprotection, but also in specific immune responses against infectious pathogens (Tsan and Gao 2004b), thermal, and osmotic stress (Dong et al. 2008; Wu et al. 2008). After being released from the cell, the HSPs act as messengers communicating the cells’ interior protein composition to the immune system for initiation of immune responses against intracellular proteins (Jolesch et al. 2012). Although expression patterns of Hsp70 and Hsc70 are quite different genes, they share common structural features including a 44-kDa N-terminal ATPase-binding domain and a 30-kDa C-terminal substrate-binding domain (Kiang and Tsokos 1998).

Recent research suggests that several members of the Hsp70 family have been identified from Crustacea, and involved in response to bacterial- and thermal stress stimuli. The expression levels of Hsp70 were rapid and showed a clear time-dependence after challenge to bacterium in the swimming crab Portunus trituberculatus and white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei (Cui et al. 2010; Zhou 2010). The Hsp70 were easily induced at hyperthermia and had a high expression level in Chinese shrimp Fenneropenaeus chinensis (Luan et al. 2010). However, very little is known about Hsp70 in response to bacterial, osmotic, and thermal stress in the mud crab Scylla even though the Hsp70 sequence of Scylla paramamosain is published (GenBank ID: EU754021).

The mud crab, Scylla spp. is a group of four commercially important portunid species that are found in intertidal and subtidal sheltered soft-sediment habitats, particularly mangroves, throughout the Indo-Pacific region (Macnae 1968; Keenan et al. 1998). In much of Southeast Asia, mud crabs are a valuable source of income for coastal communities (Walton et al. 2006a, b). Considering its high commercial interest, study focuses on the bacterium Vibrio alginolyticus which caused many diseases, such as exoskeleton ulcer disease and black gill diseases, has received increasing attention (Xia et al. 2010). Otherwise, osmotic and thermal stress can affect the antibacterial activity of S. paramamosain (Ding et al. 2010; Ma et al. 2010). The main objectives in the present study are: (1) to investigate the mRNA expression of the inducible Hsp70 in hemocytes for the bacterial, osmotic, and thermal stress, (2) to research the antimicrobial activities of recombinant Hsp70, (3) to select single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the inducible Hsp70 gene. These results may help to better understand the immune defense mechanisms in the mud crab.

Materials and methods

Animal and sample treatment

Crabs (S. paramamosain), averaging 5.8 ± 0.6 cm in carapace length, 9.0 ± 0.8 cm in carapace width and 120 ± 8 g in body weight, were collected from a commercial farm in Zhangzhou, China. The normal salinity of the seawater was 15 ‰, the normal temperature was maintained at 23 ± 2 °C and the crabs were fed on live clam (Ruditapes philippinarum) once daily in the morning. All of the animals were intact, with no injury or missing appendage. Total RNA was extracted from the mud crab tissues using Trizol RNA isolation reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and the quality was monitored by agarose gel electrophoresis. Genomic DNA was removed by DNase I (TaKaRa) digestion and the RNA concentrations were determined using UV spectrophotometry.

For the bacterial stress, 120 crabs were divided into two groups with 60 in each. The crab of experimental group was injected with 20 μl live V. alginolyticus (dissolved in saline, pH 7.0, 107 CFU/ml) into the arthrodial membrane of the last walking leg. In the control group, each crab was injected with 20 μl saline. Then, the crabs were returned to the culture tanks and every four individuals were randomly sampled at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, 72, and 96 h post-injection.

For the osmotic stress, a total of 100 crabs (the original culture salinity is 15 ‰) were employed. Compared to 15 ‰ (normal salinity), 30 ‰ (high salinity) were selected as the stress salinity to test. Half of them were put into normal salinity water, and the rest were treated at high salinity water. At selected times (0, 12, 24, 36, 72, and 96 h) after the osmotic stress, four specimens in each treatment were randomly sampled to analyze the expression levels of Hsp70.

For the thermal stress, a total of 50 crabs were employed, 10 crabs were used at each of the selected temperatures (10, 15, 25, 32, and 36 °C). The normal temperature for the culture of crabs is 25 °C, but water temperature and salinity will change with seasons at about 11–36 °C and 5–33 ‰ in the crabs’ natural habitat, respectively. The pre-experiment indicated that the expression levels of Hsp70 had a significant alteration at 6 h, so the 6 h was selected for this experiment. After 6 h (at the normal salinity 15 ‰), four individuals in each treatment were randomly sampled to analyze the expression levels of Hsp70.

Genomic DNA amplification of Hsp70

High-molecular mass genomic DNA was isolated from 30 samples. In order to determine whether the Hsp70 contained introns, genomic DNA PCR was performed with three pairs of gene-specific primers HspF1 and HspR1, HspF2 and HspR2, HspF3, and HspR3 (Table 1) designed according to the full-length cDNA of Hsp70 (GenBank ID: EU754021.1). The PCR was performed in a 50-μl reaction volume containing 2.0 μl cDNA template, 1 mM each of primers and 0.4 U of Taq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa), using a thermal cycling profile of 3 min at 94 °C for 1 cycle, 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 50 °C, 3 min at 72 °C for 42 cycles; 10 min at 72 °C, held at 10 °C. PCR products were analyzed by 1.0 % agarose gel and sequenced.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study

| Name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Position | PCR objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| HspF1 | GCTCAAACACCGAGTGAAAGA | 15–35 | Genomic cloning and SNP detection |

| HspR1 | AAACCGTAGGCGATGGCTG | 646–664 | Genomic cloning and SNP detection |

| HspF2 | ATCGCCTACGGTTTGGAC | 651–668 | Genomic cloning and SNP detection |

| HspR2 | GGTGAAGGTCTGGGTTTGT | 1379–1397 | Genomic cloning and SNP detection |

| HspF3 | TCTCTCACTGGGTATTGAAACTGCT | 1304–1328 | Genomic cloning and SNP detection |

| HspR3 | TAAGGAATGAGAATAGAGTCAGAAAAC | 2131–2157 | Genomic cloning and SNP detection |

| Hsp-q1 | CCCCACCAAACAAACCCAGA | 1370–1389 | Real-time PCR |

| Hsp-q2 | CAGCAGACACATTGAGGATACCA | 1559–1581 | Real-time PCR |

| β-actin F | GAGCGAGAAATCGTTCGTGAC | 683–703 | Internal control |

| β-actin R | GGAAGGAAGGCTGGAAGAGAG | 849–869 | Internal control |

| HspF4 | CGAGCTCATGTCTAAGGGAGCAGCTGTC | 111–132 | Prokaryotic expression |

| HspR4 | CCCAAGCTTTTAATCGACCTCCTCGATG | 2044–2063 | Prokaryotic expression |

Tissues distribution and expression profile of Hsp70

Total RNA was isolated from various tissues including midgut, stomach, hepatopancreas, epidermis, thoracic ganglion, gill, eyestalk, heart, brain, muscle, and hemocytes of three unstressed crabs. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA with a Revert AidTM First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas) using the oligo (dT)18 primer. The fluorescent quantitative real-time PCR was carried out to determine the mRNA distribution in different tissues and the temporal expression profile in the hemocytes after bacterial, osmotic, and thermal stress. Gene-specific primers, Hsp-q1 and Hsp-q2 (Table 1) were used to amplify the corresponding products of 212 bp from cDNA template. In order to compare the relative levels of expression of Hsp70 in samples, the housekeeping gene β-actin (GenBank ID: GU992421) was also amplified with the same cDNA samples using the primers β-actin F and β-actin R (Table 1). The PCR was carried out in a total volume of 20 μl, containing 10 μl of 2× SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa), 0.8 μl of each primer (10 μM), 2 μl of the diluted cDNA and 6.4 μl ddH2O. The thermal profile for real-time PCR was 30 s at 95 °C for 1 cycle, 5 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, 30 s at 72 °C for 40 cycles.

All experiments were replaced quintuplicate. Fold change for the gene expression relative to controls was determined by the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). All data were expressed as mean ± SD (standard deviation) representing the relative expression ratio. After challenge to bacterial and osmotic stress, the significance of differences in expression were determined using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple range tests; The significance of differences in expression after thermal stress was determined using one-way ANOVA; with a threshold significance level of P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0. Then, the Hsp70 expression levels were analyzed using independent samples t test, and the P values < 0.05 and 0.01 were considered statistically significant with * and **, respectively.

Sequence analysis

The obtained sequence of the intron of Hsp70 genomic DNA was compared with the known Hsp70 cDNA sequences in the NCBI database using the BLAST program (htttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). The genomic polymorphism analysis was performed by Sequencher 4.1.4.

Construction of Hsp70 expression plasmid

The ORF of Hsp70 was amplified using the primers HspF4 and HspR4 by PCR. Following amplification the cDNA fragment was digested with Kpn Ι and Sac Ι and ligated into the Kpn Ι, Sac Ι-digested vector pET32a. The ligated product (pET32a/rHsp70) was transformed into competent Escherichia coli for DNA sequence determination. The pET32a/rHsp70 construct was transformed into Rosetta cells for protein expression. Overnight culture of a single colony was diluted (1:100) with Luria–Bertani medium and incubated at 37 °C with vigorous shaking to OD600 of 0.4–0.6. IPTG was added at a final concentration of 0.2 mM to induce the protein expression for a period of 6 h at 25 °C. The protein extract was analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Purification of rHsp70

Bacteria was pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in 40 mL lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 5 mM β-ME, 1 mM PMSF). The cells were broken by supersonic wave at 10 °C and centrifuged at 20,000×g, 4 °C for 30 min. The supernatant was collected and loaded onto a Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Novagen) affinity column. The recombinant protein was eluted with four concentration of elution buffers (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 50/100/200/500 mM imidazole) and dialyzed in PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.4) at 4 °C overnight. The extracted protein was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot with mouse anti-(his-tag) IgG as the first antibody (Novagen) and goat anti-mouse IgG-alkaline phosphatase conjugate as the secondary antibody. A protein assay kit (Solarbio) was used to determine the protein concentration.

Antimicrobial activity

The antibacterial activities of the rHsp70 were tested at pH 7.4. The bacteria were cultured on medium. Antibacterial activity was monitored by a liquid growth inhibition assay against Gram-positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-negative bacteria V. alginolyticus, as previously described (Xavier et al. 2002). Briefly, the bacteria were cultured on Mueller–Hinton broth medium and Difco marine broth. Then, logarithmic phase bacterial cultures were diluted in PBS to A600 = 0.003, which is approximately equivalent to 3–6 × 105 CFU/mL. Diluted bacteria (90 μl) were mixed with 10 μl of either PBS (control) or the rHsp70 protein in wells of a microtitration plate. The bacterial growth was monitored, after an overnight incubation at 25 °C, by measuring the change in the absorbance of the culture at 600 nm using a microplate reader. This assay was performed in triplicate.

Results

Genomic DNA amplification of Hsp70

The genomic DNA fragments at positions 15–2,157 bp of Hsp70 sequences were amplified for Hsp70 gene. Only one intron was found in this gene, which was 1,341 bp in the 5′ UTR between 106–107 bp of Hsp70 cDNA. Containing intron the Hsp70 was 3,558 bp, six SNPs within 3,484 bp in length were detected by direct sequencing from 30 samples. The SNPs were 270 T/G, 759C/A, 760 G/T, 762A/T, 1024C/T, 2534 G/A. The distribution frequencies of these mutations were 0.50, 0.40, 0.20, 0.20, 0.40 and 0.29 for each allele, respectively. Analysis of these mutations, only the 2534 G/A was found in the ORF region and others in the intron region of this gene. The observed SNPs were detected in the coding region of the Hsp70 gene was synonymous polymorphisms.

Tissue distribution

Expression analysis of Hsp70 mRNA by real-time PCR, with β-actin as an internal control, showed that this gene was expressed constitutively in all examined tissues with different expression levels (Fig. 1). The obviously high levels of Hsp70 transcript were in the hepatopancreas, stomach, gill, whereas only trace amount was detected in eyestalk. The highest Hsp70 expression level was in hepatopancreas, which was higher than those in other tissues.

Fig. 1.

Tissues distribution of Hsp70 by real-time PCR. Each bar represents the mean value from four determinations with standard error. 1 midgut; 2 stomach; 3 hepatopancreas; 4 epidermis; 5 thoracic ganglion; 6 gill; 7 eyestalk; 8 heart; 9 brain; 10 muscle; 11 hemocytes

Expression profiles of Hsp70 after injection with bacteria

Real-time PCR analysis of this gene expression in hemocytes showed a clear time-dependent expression pattern during the 96 h (Fig. 2). Statistical analysis revealed that the expression level of the Hsp70 had a significant difference at different time after challenge to bacteria. There were two peaks in the mRNA expression profile post stimulation. The Hsp70 mRNA level was up-regulated to reach the first peak at 3 h, which was 1.6-fold to that in control group (P < 0.01) after stimulation by V. alginolyticus. Afterward, the expression level dropped gradually, and decreased to lower level at 24 h (lower than control, P > 0.05). As time progressed, the expression level reached the highest level at 72 h (1.9-fold, P < 0.01), and recovered to lower level at 96 h.

Fig. 2.

The Hsp70 transcript temporal expression in hemocytes after V. alginolyticus stimulation measured by real-time PCR. Each bar represents the mean value from four determinations with standard error. The hemocytes were collected from four individual crabs at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, 72, and 96 h post-injection. Significant differences across control are indicated with an asterisk at P < 0.05, and with two asterisks at P < 0.01

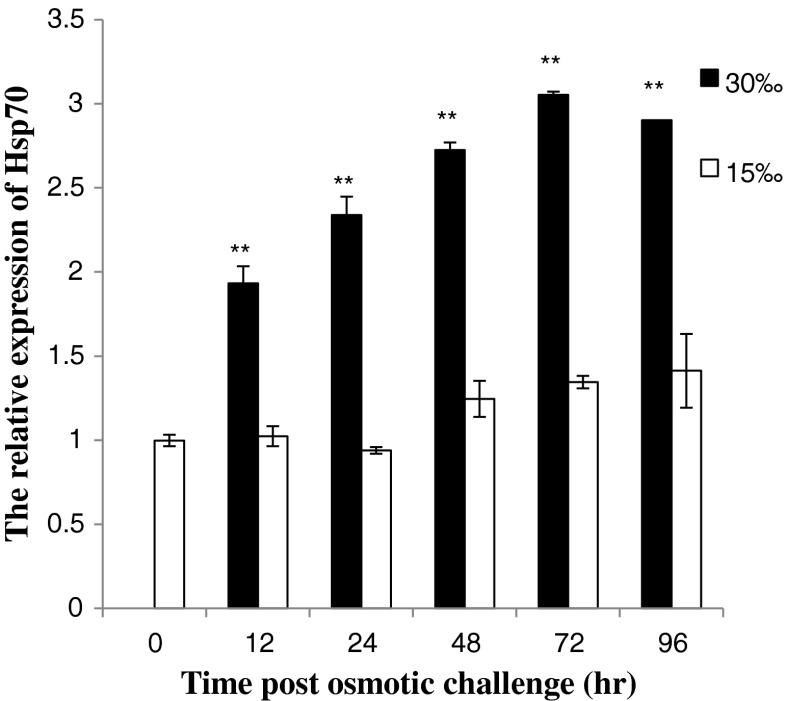

Expression profiles of Hsp70 after osmotic stress

The temporal expression of Hsp70 transcript in hemocytes of the mud crab stressed by high salinity was recorded by real-time PCR (Fig. 3). Higher level was observed at 12 h, which was 1.9-fold to that in control group (P < 0.01) after high osmotic stress. As time progressed, the expression of Hsp70 increased gradually, and reached the highest level at 72 h (2.3-fold, P < 0.01).

Fig. 3.

The Hsp70 transcript temporal expression in hemocytes after osmotic stress measured by real-time PCR. Each bar represents the mean value from four determinations with standard error. The hemocytes were collected from four individual crabs at 0, 12, 24, 36, 72, and 96 h. Significant differences across control are indicated with an asterisk at P < 0.05, and with two asterisks at P < 0.01

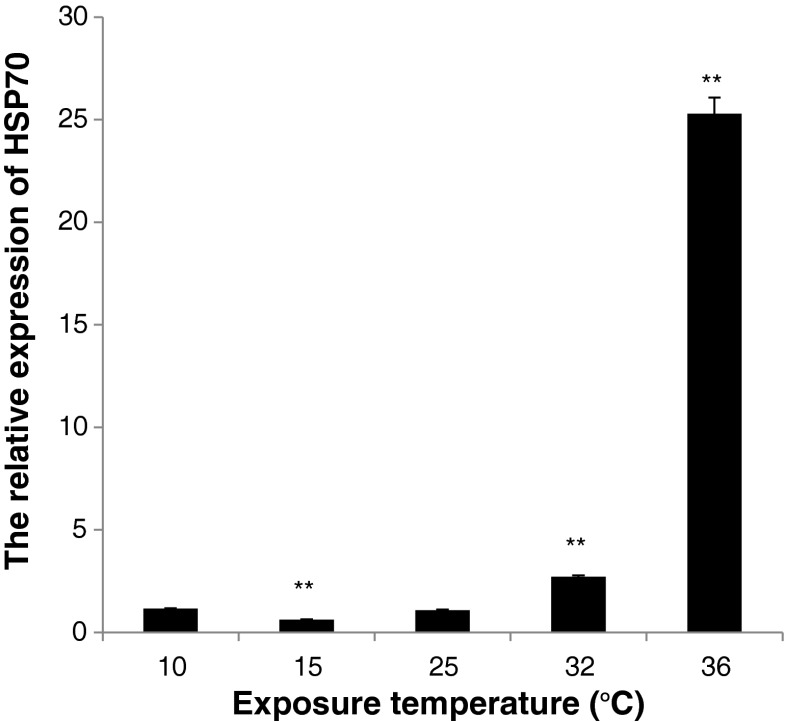

Expression profiles of Hsp70 after thermal stress

In order to know whether the temperature influences Hsp70 expression, Hsp70 mRNA level in hemocytes, after crabs were stressed for different temperatures, was detected by real-time PCR (Fig. 4). There was no significant difference expression level of Hsp70 between 10 °C and 25 °C. In this study, the lowest expression level was observed at 15 °C (lower than 25 °C, P < 0.01). The highest expression level of Hsp70 was observed at 36 °C, which was significantly higher than that detected at 25 °C (23.3-fold, P < 0.01).

Fig. 4.

The Hsp70 transcript temporal expression in hemocytes after thermal stress measured by real-time PCR. Each bar represents the mean value from four determinations with standard error. The hemocytes were collected from four individual crabs at 10, 15, 25, 32, and 36 °C after 6 h; 25 °C was selected to the control group. Significant differences across control are indicated with an asterisk at P < 0.05, and with two asterisks at P < 0.01

Bacterial expression of the rHsp70

The recombinant protein of the expected molecular weight was detected on the SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5). Compared to the IPTG uninduced groups, the IPTG induced groups had an obvious band. Result of the SDS-PAGE indicated that the recombinant protein was soluble and mainly in the supernatant. The molecular mass of the detected rHsp70 band was ∼95 kDa, which was the expected size of the recombinant protein.

Fig. 5.

Expression analysis of recombinant protein Hsp70. 1–3 Supernatant, precipitation and all proteins of induced of recombinant protein Hsp70; 4–6 supernatant, precipitation and all proteins of uninduced of recombinant protein Hsp70; M protein marker

Purification of rHsp70 and antimicrobial activity

With the aid of the series of His6-tag residues in the recombinant protein, we got the recombinant protein through an affinity column. SDS-PAGE analysis at different concentrations of elution buffer indicated that the proper concentration of elution buffer is 100 mM imidazole. The rHsp70 protein was detected by using SDS-PAGE and Western blot (Fig. 6). The results indicated that the recombinant protein was pure with no contaminants and the concentration was 30 μM. By using the antibacterial assay, no obvious antimicrobial activity has been found for the recombinant protein.

Fig. 6.

Purification of rHsp70; a SDS-PAGE analysis of the rHsp70 protein which was eluted by different concentration of elution buffers; b western blot analysis of the expression of rHsp70 protein. a1–4 The rHsp70 protein was eluted by 50, 100, 200, 500 mM imidazole, respectively; M protein marker

Discussion

Tissue distribution of Hsp70

The expression analysis of Hsp70 showed that the Hsp70 was ubiquitously expressed in all examined tissues of S. paramamosain, indicating that Hsp70 was synthesized under unstressed conditions. Compared to other tissues, hepatopancreas is the major metabolic center responsible for the production of reactive oxygen species and is an important tissue for immune defenses in crustaceans (Söderhäll and Cerenius 1998). The highest expression level of Hsp70 in hepatopancreas showed that Hsp70 might be involved in immune reactions and metabolism. Stomach and gill contact more directly to the external environment than other organs. In addition, gill is known to play key roles in osmoregulation, detoxification, and defense mechanisms (Alejandra et al. 2007). The higher expression level in them suggested that Hsp70 is a good biomarker for exposure.

Expression profiles of Hsp70 after bacterial expression and purification of rHsp70

Hemocytes play an important role in the immune response against pathogens, and also participate in cellular encapsulation and phagocytosis (Söderhäll and Cerenius 1998; Cerenius and Söderhäll 2004).

Here, we detected the Hsp70 expression levels in hemocytes after stimulated with V. alginolyticus, osmosis and hyperthermia. The transcriptional expression of Hsp70 showed a clear time-dependent response in hemocytes after the crabs were challenged with V. alginolyticus. The first peak of the Hsp70 expression level after stimulation was observed at 3 h and the maximum level at 72 h (Fig. 2). This date suggests that the Hsp70 was induced rapidly to protect the denatured proteins in the host cells when infected with bacteria (Gao et al. 2008). Such rapid induction expression level was similar to the previous study in white shrimp L. vannamei (Zhou et al. 2010). Furthermore, the expression level dropped progressively from 6 to 48 h nearly to the original level but increased about 1.9-fold and reached the maximum at 72 h. At 96 h, the expression level of Hsp70 recovered nearly to the original level (Fig. 2). This suggested that Hsp70 in S. paramamosain possesses a long-term response to bacterial challenge which was different from swimming crab P. trituberculatus and bay scallop Argopecten irradians (Cui et al. 2010; Song et al. 2006). The difference may be affected by the intron. In the Hsp70 family, introns are generally found only in constitutively expressed genes but not found in the inducible forms (Yost and Lindquist 1986). Recently, introns have been found in the inducible Hsp70 (Muller et al. 1992; Stefani and Gomes 1995; Vincent et al. 2007). It was suggested that the lack of introns in inducible Hsp70s allows rapid transcription and accumulation on stress, the nuclear export signal being probably provided by the mRNA secondary and tertiary structure (Huang et al. 1999). In our study, an intron present in Hsp70 gene may be the reason of the long-term response to bacterial challenge.

To determine whether the Hsp70 protein have antimicrobial activities, we obtained rHsp70 by using the bacterial expression system. At last, a recombinant protein of ∼95 kDa was produced (Figs. 4 and 5). This protein is ∼25 kDa larger than the predicted molecular mass of the Hsp70 protein (∼70 kDa) as a result of the addition of some amino acids at the N-terminal of the recombinant protein. By using the antimicrobial tests, no obvious antimicrobial activity has been found for the rHsp70. It is reported that prokaryocyte systems have expressed some antimicrobial peptides and have antimicrobial activity, such as an insect cecropin in E. coli (Xu et al. 2007), a crab scygonadin in E. coli (Peng et al. 2010). Based on the present data, we deduced that the Hsp70 may not have the nature of the antimicrobial peptides.

Expression profiles of Hsp70 after osmotic and thermal stress

As stress proteins, HSPs are expressed in response not only to a wide range of biotic stressors, but also to physical and chemical stressors such as thermal and osmotic stress (Dong et al. 2008). Osmotic stress plays an important role in the induction of Hsp70 in aquatic animals (Yokoyama et al. 2006). In the present study, the Hsp70 was induced by the high salinity (30 ‰) (Fig. 3). The expression level was remained higher than the control (15 ‰) for at least 96 h after osmotic challenge. At 72 h the expression level of Hsp70 reached the highest level (2.3-fold). This result indicated that high salinity was a stressor in S. paramamosain. At a high salinity, the expression of Hsp70 could enhance the resistance of S. paramamosain against the change of salinity. The mechanism behind this phenomenon might be that (1) Hsp70 provides a rapid protective measure until organic osmolytes are fully accumulate (Cohen et al. 1991); (2) the osmotic challenge increases the rate of metabolism and enhances the stress response, which makes the organism vulnerable to germs for the disorder physiology and low immunity. The high salinity concentration could affect the activity of immune factors, such as lysozyme, phenoloxidase and peroxide enzyme (Ma et al. 2010). Heat-inducible forms of Hsp70 play a central role in stress tolerance by promotion of growth at moderately high temperature and/or protecting organisms from death at extreme temperatures (Ravi et al. 2004). In this study, transient expression in hemocytes was analyzed after thermal challenge 6 h (Fig. 4). Compared to the normal temperature (25 °C), the highest and the lowest expression level of Hsp70 was observed at 36 °C (23.3-fold) and 15 °C, respectively. This response behavior indicated that the Hsp70 were easily induced at hyperthermia and sensitive to temperature variations as in shrimp F. chinensis and oyster Ostrea edulis (Annamaria et al. 2004; Luan et al. 2010). Based on the present data, we inferred that Hsp70 played a crucial role in protecting the cells from damage.

Analysis of SNPs

An SNP is a single nucleotide change in a DNA sequence, and constitutes a bi-allelic, co-dominant marker that contains less information than equivalent multi-allelic microsatellite loci (Vignal et al. 2002). Some SNPs occur in coding regions and have been shown to affect protein function. Thus, certain SNPs may influence phenotypic variation directly among cultured individuals (Beuzen et al. 2000). Furthermore, Some SNPs have effects on transcription, splicing, mRNA transport or translation, even the phenotype, though they do not affect protein sequence (Goymer 2007). Previous study has reported that the genetic polymorphisms of Hsp70 SNP 892C/T is likely associated with a virus-resistance trait in population of white shrimp L. vannamei (Zeng et al. 2008). So, further study will analyze the linkage between the genetic polymorphisms of Hsp70 and the bacteria, high salinity and heat shock-resistance trait in S. paramamosain, in order to be applied in molecular marker-assisted breeding.

References

- Alejandra CS, Rogerio RSM, Teresa GG, Jorge HL, Alma BPU, Adriana MA, Gloria YP. Transcriptome analysis of gills from the white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei infected with white spot syndrome virus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2007;23:459–472. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annamaria P, Paola V, Elena F. Expression of cytoprotective proteins, heat shock protein 70 and metallothioneins, in tissues of Ostrea edulis exposed to heat and heavy metals. Cell Stress Chaper. 2004;9:134–142. doi: 10.1379/483.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuzen ND, Stear MJ, Chang KC. Molecular markers and their use in animal breeding. Vet J. 2000;160:42–52. doi: 10.1053/tvjl.2000.0468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerenius L, Söderhäll K. The prophenoloxidase-activating system in invertebrates. Immunol Rev. 2004;198:116–126. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen DM, Wasserman JC, Gullans SR. Immediate early gene and HSP70 expression in osmotic stress in MDCK cells. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:C594–601. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.261.4.C594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui ZX, Liu Y, Luan WS, Li QQ, Wu DH, Wang SY. Molecular cloning and characterization of a heat shock protein 70 gene in swimming crab (Portunus trituberculatus) Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2010;28:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding XF, Yang YJ, Jin S, Wang GL. The stress effects of temperature fluctuation on immune factors in crab Scylla serrata. Fish Sci. 2010;29:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dong YW, Dong SL, Meng XL. Effects of thermal and osmotic stress on growth, osmoregulation and Hsp70 in sea cucumber (Apostichopus japonicus Selenka) Aquaculture. 2008;276:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.01.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coux G, Mouquelar VS. Amphibian oocytes release heat shock protein A during spawning: evidence for a role in fertilization. Biol Reprod. 2012;87:33. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.100982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q, Zhao JM, Song LS, Qiu LM, Yu YD, Zhang H, Ni DJ. Molecular cloning, characterization and expression of heat shock protein 90 gene in the haemocytes of bay scallop Argopecten irradians. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2008;24:379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrmann M, Brunner M, Pfister K, Reichle A, Kremmer E, Multhoff G. Differential up-regulation of cytosolic and membrane-bound heat shock protein 70 in tumor cells by anti-inflammatory drugs. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3354–3364. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goymer P. Synonymous mutations break their silence. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:92. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Wimler KM, Carmichael GG. Intronless mRNA transport elements may affect multiple steps of pre-mRNA processing. EMBO J. 1999;18:1642–1652. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolesch A, Elmer K, Bendz H, Issels RD, Noessner E. Hsp70, a messenger from hyperthermia for the immune system. Eur J Cell Biol. 2012;91(1):48–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan CP, Davie PJF, Mann DL. A revision of the genus Scylla de Haan, 1833 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura: Portunidae) Raffles B Zool. 1998;46:217–245. [Google Scholar]

- Kiang JG, Tsokos GC. Heat shock protein 70 kDa: molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;80:183–201. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7258(98)00028-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kregel KC. Heat shock proteins: modifying factors in physiological stress responses and acquired thermotolerance. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:2177–2186. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01267.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C (T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan W, Li F, Zhang J, Wen R, Li Y, Xiang J. Identification of a novel inducible cytosolic Hsp70 gene in Chinese shrimp Fenneropenaeus chinensis and comparison of its expression with the cognate Hsc70 under different stresses. Cell Stress Chaper. 2010;15:83–93. doi: 10.1007/s12192-009-0124-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma YC, Yang YJ, Wang GL. Effects of salinity challenge on the immune factors of Scylla serrata. Acta Agriculturae Zhejiangensis. 2010;22:479–484. [Google Scholar]

- Macnae W. A general account of the fauna and flora of mangrove swamps and forests in the Indo-West-Pacific region. Adv Mar Biol. 1968;6:73–270. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2881(08)60438-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muller FW, Igloi GL, Beck CF. Structure of a gene encoding heat-shock protein HSP70 from the unicellular alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Gene. 1992;111:165–173. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90684-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multhoff G (2006) Heat shock proteins in immunity. Handbook of experimental pharmacology, vol. 172, Springer, Berlin, pp 279–304 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Park JH, Lee JJ, Yoon S, Lee JS, Choe SY, Choe J, Park EH, Kim CG. Genomic cloning of the Hsc71 gene in the hermaphroditic teleost Rivulus marmoratus and analysis of its expression in skeletal muscle: identification of a novel muscle-preferred regulatory element. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;9:3041–3050. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.14.3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H, Yang M, Huang WS, Ding J, Qu HD, Cai JJ, Zhang N, Wang KJ. Soluble expression and purification of a crab antimicrobial peptide scygonadin in different expression plasmids and analysis of its antimicrobial activity. Protein Expr Purif. 2010;70:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranford JC, Coates ARM, Henderson B. Chaperonins are cell-signalling proteins: the unfolding biology of molecular chaperones. Exp Rev Mol Med. 2000;201:1–17. doi: 10.1017/S1462399400002015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi V, Kubofcik J, Bandopathyaya S, Geetha M, Narayanan RB, Nutman TB, Kaliraj P. Wuchereria bancrofti: cloning and characterization of heat shock protein 70 from the human lymphatic filarial parasite. Exp Parasitol. 2004;106:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderhäll K, Cerenius L. Role of prophenoloxidase-activating system in invertebrate immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:23–28. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(98)80026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song LS, Wu LT, Ni DJ, Chang YQ, Xu W, Xing KZ. The cDNA cloning and mRNA expression of heat shock protein70 gene in the haemocytes of bay scallop (Argopecten irradians, Lamarck 1819) responding to bacteria challenge and naphthalin stress. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2006;21:335–345. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefani RM, Gomes SL. A unique intron-containing hsp70 gene induced by heat shock and during sporulation in the aquatic fungus Blastocladiella emersonii. Gene. 1995;152:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00645-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsan MF, Gao BC. Heat shock protein and innate immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2004;1:274–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsan MF, Gao BC. Cytokine function of heat shock proteins. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C739–744. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00364.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignal A, Milan D, SanCristobal M, Eggen A. A review on SNP and other types of molecular markers and their use in animal genetics. Gene Sel Evol. 2002;34:275–305. doi: 10.1186/1297-9686-34-3-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent L, Marie C, Brigitte M, Benoît C. Identification of new subgroup of HSP70 in Bythograeidae (hydrothermal crabs) and Xanthidae. Gene. 2007;396:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton MEM, Vay LL, Lebata JH, Binas J, Primavera JH. Seasonal abundance, distribution and recruitment of mud crabs (Scylla spp.) in replanted mangroves. Est Coast Shelf Sci. 2006;66:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2005.09.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walton MEM, VayLL TLM, Ut VN. Significance of mangrove-mudflat boundaries as nursery grounds for the mud crab, Scylla paramamosain. Mar Biol. 2006;149:1199–1207. doi: 10.1007/s00227-006-0267-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu R, Sun Y, Lei LM, Xie ST. Molecular identification and expression of heat shock cognate 70 (HSC70) in the pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Mol Biol. 2008;42:234–242. doi: 10.1134/S002689330802009X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier L, Hiroko S, Jane CB, Mark EW, Vaughn EO, James MC, Jon C, Van O, Victor N, Steven WT, Chisato S, Philippe B. Discovery and characterization of two isoforms of moronecidin, a novel antimicrobial peptide from hybrid striped bass. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5030–5039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109173200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia XA, Wu QY, Li YY. Isolation and identification of two bacterial pathogens from mixed infection mud crab Scylla serrata and drug therapy. J Trop Oceanogr. 2010;29:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Jin F, Yu X, Ji S, Wang J, Cheng H, Wang C, Zhang W. Expression and purification of a recombinant antibacterial peptide, cecropin, from Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 2007;53:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama S, Koshio S, Takakura N, Oshida K, Ishikawa M, Gallardo-Cigarro F. Effect of dietary bovine lactoferrin on growth response, tolerance to air exposure and low salinity stress conditions in orange spotted grouper Epinephelus coioides. Aquaculture. 2006;255:507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2005.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yost HJ, Lindquist S. RNA splicing is interrupted by heat shock and is rescued by heat shock protein synthesis. Cell. 1986;45:185–193. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90382-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng DG, Chen XH, Li YM, Peng M, Ma N, Jiang WM, Yang C, Li M. Analysis of Hsp70 in Litopenaeus vannamei and detection of SNPs. J Crustac Biol. 2008;28:727–730. doi: 10.1651/08-3019.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Wang WN, He WY, Zheng Y, Wang L, Xin Y, Liu Y, Wang AL. Expression of HSP60 and HSP70 in white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei in response to bacterial challenge. J Invertebr Pathol. 2010;103:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]