ABSTRACT

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP) is a rare interstitial lung disease characterized by subacute dyspnea, peripheral infiltrates on imaging, and pulmonary eosinophilia. We report a case of a 48-year-old man who presented to a “minute clinic” with cough and dyspnea. After improvement on a short course of steroids for a presumptive diagnosis of bronchospasm, he presented to our hospital with symptom recurrence. Computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed peripheral infiltrates and bronchoscopy confirmed pulmonary eosinophilia. In this clinical vignette, we review the typical presentation of chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, the differential diagnosis of pulmonary infiltrates with eosinophilia, and the challenges of diagnosing a rare condition that may mimic more common causes of dyspnea, especially in a “minute clinic” setting.

KEY WORDS: chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, pulmonary eosinophilia, retail clinics

INTRODUCTION

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP) is an idiopathic interstitial lung disease characterized by an accumulation of eosinophils in the lungs. It can present with various symptoms including cough and progressive dyspnea.1, 2 Asthma precedes CEP in half of all cases and peripheral eosinophilia is present at presentation in 80–90 %.3 Fewer than 10 % of patients resolve spontaneously, but CEP is very responsive to steroid therapy.4

We report a case of a 48-year-old man with no past medical history who presented to a retail (or “minute”) clinic with subacute shortness of breath, responsive to oral steroids. Symptoms recurred after steroid cessation and he re-presented to our hospital. Imaging revealed peripheral infiltrates and bronchoalveolar lavage demonstrated an abnormally high percentage of eosinophils. His symptoms improved rapidly with prednisone.

CASE REPORT

A 48-year-old man with no pertinent medical history presented to our Emergency Department with approximately 1 month of shortness of breath. Two weeks prior to presentation to the Emergency Department, he was seen at a “minute clinic” for the same complaint. At this clinic, no wheezing was documented and no other exam abnormalities were noted. Neither labs nor imaging were obtained. He was given the diagnosis of “bronchospasm,” started on daily prednisone, and given an albuterol inhaler to use as needed. After 2 days of prednisone, the patient felt remarkably better. He completed a 5 day course of treatment.

Symptoms recurred 1 day after completion of steroids. He described an “inflamed sensation” in his chest and felt that his lungs “got stuck” with deep inspiration. He noted profound dyspnea on exertion with no response to albuterol. He denied cough, sore throat, or wheezing. He had no subjective fever or chills and no nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. He had no changes in urination, rash, or arthralgias. He had no history of any similar prior episodes. He worked as an event planner. He was a lifelong non-smoker and denied any exposure to mold, dust, or other particulate matter.

On initial examination, the patient was afebrile with a blood pressure of 152/94 mmHg, pulse of 93 beats per minute, and a respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute. His oxygen saturation on room air was 96 % and he was in no distress. Inspiratory crackles were heard throughout the lungs, more prominently at the bases. Joint and skin examination was normal. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable.

Initial laboratory tests, including basic metabolic panel, urinalysis, and complete blood count with differential, were all within normal limits. N-terminal pro-BNP and troponin were not elevated. HIV antibody testing and urine cocaine screen were negative.

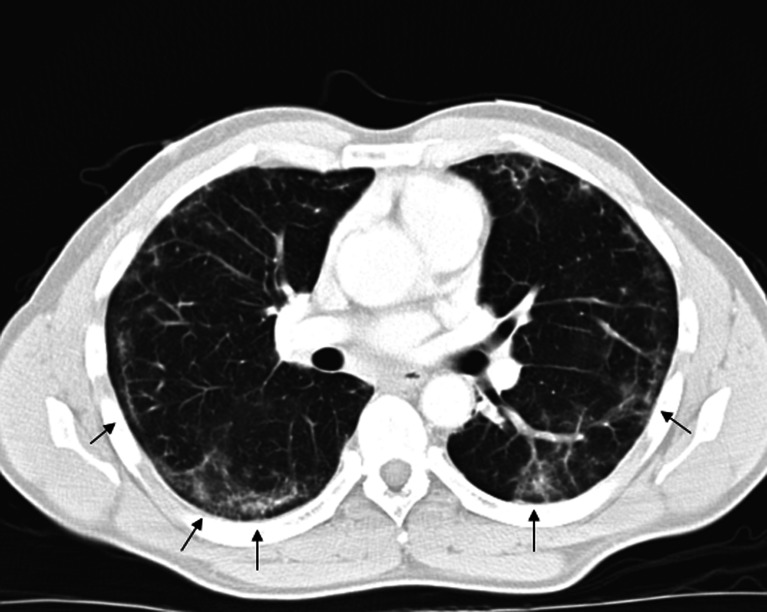

Chest X-ray demonstrated bibasilar patchy infiltrates. Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed bilateral peripheral and lower lobe interstitial infiltrates with air bronchograms (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Chest computed tomography (CT) with peripheral interstitial ground-glass infiltrates (arrows).

The patient was admitted and levofloxacin was administered for possible community-acquired pneumonia. Because of the atypical imaging findings and response to steroids, the patient underwent further testing. On bronchoscopy, no endobronchial lesions or secretions were seen. Bronchoalveolar lavage revealed 267 nucleated cells per high-powered field with marked pulmonary eosinophilia (23 %). Based on the key symptoms—subacute dyspnea, dry cough, response to steroids—combined with the characteristic CT findings and pulmonary eosinophilia, the patient was diagnosed with CEP.

The patient was started on prednisone and symptoms resolved within 1 day. He was discharged on prednisone and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis with a plan for a minimum of 3 months of treatment. Following discharge, the patient missed several follow-up appointments, but was seen again in clinic 7 months later. At that time, he was asymptomatic and working without limitations. Follow-up imaging showed significant interval improvement in interstitial infiltrates compared with the admission x-ray, with persistence of small bibasilar lung infiltrates. Given his clinical improvement, he was not prescribed chronic steroid therapy and was followed closely in clinic.

DISCUSSION

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP) was first described by Carrington et al. in 1969.5 CEP is a rare disorder that likely affects less than 1 person per 100,000 per year.3–5 It affects women more often than men (approximate 2:1 ratio) and most commonly presents in patients in their fifth and sixth decades.3, 4 CEP is not associated with smoking, but asthma is a common comorbidity, present in greater than 50 % of patients.3–5 An increase in CEP incidence has been documented in patients with prior radiation for breast cancer, but no known trigger exists in the majority of cases.6, 7 Typical symptoms of CEP include cough, progressive dyspnea, fever, weight loss, wheezing, and night sweats.1, 3–5 Cough is nearly universal as well as dyspnea, but respiratory failure is rare.3–5 Non-pulmonary symptoms (aside from fever, fatigue, and weight loss) are uncommon.2, 3

Expected laboratory findings include elevated inflammatory markers (such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein) and peripheral eosinophilia (seen in 80–90 % of cases).3, 8–10 Chest X-ray may reveal bilateral peripheral or pleural opacities portraying the “photographic negative” of that seen in pulmonary edema (as originally described by Carrington),5 but this finding is neither sensitive nor specific for CEP.6, 11 Of note, patients with minimal findings on chest X-ray may have notable opacities on high-resolution CT.2 Characteristic CT findings include areas of bilateral ground-glass opacity distributed peripherally in the middle or lower lungs. Bronchoalveolar lavage with > 25 % eosinophils is highly suggestive of CEP.12 Pulmonary tissue biopsy often demonstrates interstitial and alveolar eosinophils with minimal fibrosis and organizing pneumonia in the setting of bronchiolitis obliterans is also a common finding.2

There are no clearly established criteria for the diagnosis of CEP. Atypical infection or malignancy may have a similar insidious onset, but neither of these is responsive to steroids and neither typically causes pulmonary eosinophilia. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and autoimmune respiratory disease (such as non-specific interstitial pneumonia) may also present with similar symptoms and imaging findings. However, none of these typically cause pulmonary eosinophilia. Once pulmonary eosinophilia is identified, CEP must be differentiated from other diseases with pulmonary infiltrates and eosinophilia (PIEs).

The differential diagnosis of PIE syndromes includes Churg-Strauss syndrome, helminthic infection, drug reaction, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), acute eosinophilic pneumonia (AEP), and CEP. Churg-Strauss syndrome should be considered when patients have extrathoracic symptoms (such as arthritis or rash). Helminthic infection should be considered when patients have a history of travel to an endemic region, and is much more likely when serologic evidence of infection is confirmed.11 ABPA is seen in patients with longstanding asthma or cystic fibrosis, is associated with a very high IgE level, and is confirmed by skin testing to aspergillus antigens. Idiopathic AEP typically presents with more severe symptoms such as marked hypoxia and symptom duration less than 1 week.2, 3, 5 AEP, in comparison with CEP, less commonly features peripheral eosinophilia and often presents after a clear inhalational precipitating event, such as recent onset of smoking.

Treatment of CEP is essential once the diagnosis is made as fewer than 10 % of cases resolve spontaneously.3, 4 Additionally, untreated cases can progress to irreversible fibrotic changes in the lung.13 Initial therapy regimen is typically 0.5 mg/kg oral prednisone daily.3, 14 In the setting of rapidly progressive respiratory failure, IV steroids are indicated. Symptoms often improve with 1 week of therapy and radiographic resolution usually occurs within 1 month.14 Peripheral eosinophilia also typically resolves with treatment.14 Steroids should be continued for at least 3 to 6 months even if symptoms resolve earlier.3, 4, 9, 14, 15Pneumocystis jiroveci prophylaxis is recommended as an adjunct to oral steroids. Symptomatic or radiographic relapse is common after cessation of therapy and may occur years after the initial episode.3, 4, 14 In cases where relapse is of particular concern, steroid therapy should be continued indefinitely.14

An interesting aspect of this case was the initial evaluation of the patient at a retail clinic. Retail or “minute” clinics have recently increased in number and have been proposed as a solution to the long waits and high costs associated with Emergency Department evaluation.16–19 Retail clinics typically use standardized algorithms for the diagnosis and treatment of common conditions such as sinusitis or urinary tract infection (UTI), and do not evaluate patients with potentially complex diagnostic needs (such as chest pain).16, 17 This algorithmic care can prove limited when a rare disease such as CEP presents with symptoms similar to a common condition such as asthma.

Retail clinics must be wary of situations when a “zebra” may mimic a common disease and find ways to ensure rare diseases are identified. One method may be to instruct patients about the expected treatment course for the presumed common disease. In this way, if symptoms do not resolve or the disease course deviates from the anticipated path, these patients will know to seek re-evaluation. Additionally, as algorithms utilized in retail clinics grow more complex, clinics may be able to select out patients that warrant additional testing despite symptoms that may be due to a common condition. However, the suggestions above have not been studied as ways to improve diagnosis or follow-up and there is currently limited research regarding methods of improving care in the retail clinic setting. In this case, by empirically treating with steroids for bronchospasm, the initial evaluation inadvertently provided our physicians with critical information for diagnosing the patient—the response of symptoms to steroids and the abrupt return of symptoms after steroid cessation—both classic features of CEP.

CONCLUSIONS

As an uncommon cause of both cough and dyspnea, CEP is a difficult diagnosis to detect, particularly in the outpatient setting. The combination of lab and x-ray findings can suggest the diagnosis, which is confirmed by bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage. Diagnosis is critical, as few cases remit spontaneously and response to steroids, although occurring after more than a minute, is dramatic.

KEY POINTS

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP) typically presents with dry cough and dyspnea for over 1 week. Peripheral eosinophilia and peripheral infiltrates on imaging may also be present.

Bronchoalveolar lavage with eosinophilic predominance confirms the diagnosis of CEP, provided that other causes of pulmonary eosinophilia have been excluded.

CEP responds rapidly to steroids, but requires a long course of therapy.

Retail (or “minute”) clinics must have heightened awareness that rare conditions which share symptoms with common diseases are difficult to diagnose through algorithmic evaluation.

Acknowledgements

All authors have read the policies as outlined by the journal.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen JN, Davis WB. Eosinophilic lung diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:1423. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.5.7952571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsuse H, Shimoda T, Fukushima C, et al. Diagnostic problems in chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. J Int Med Res. 1997;25:196. doi: 10.1177/030006059702500404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchand E, Cordier JF. Idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:11. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alam M, Burki NK. Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia: a review. South Med J. 2007;100(1):49–53. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000242863.17778.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrington CB, Addington WW, Goff AM, et al. Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1969;280(15):787–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196904102801501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaensler EA, Carrington CB. Peripheral opacities in chronic eosinophilic pneumonia: the photographic negative of pulmonary edema. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1977;128:1. doi: 10.2214/ajr.128.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marchand E, Etienne-Mastroianna B, Chanez P, Lauque D, Leclerc P, Cordier JF. Idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia and asthma: how do they influence each other? Eur Respir J. 2003;22:8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00085603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laufs U, Schneider C, Wasserman K, Erdmann E. Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia with atypical radiographic presentation. Respiration. 1998;65:323. doi: 10.1159/000029287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marchand E, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Lauque D, Durieu J, Tonnel AB, Cordier JF. Idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia: a clinical and follow-up study of 62 cases. Med (Baltimore) 1998;77:299. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199809000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jederlinic PJ, Sicilian L, Gaensler EA. Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. A report of 19 cases and a review of the literature. Med (Baltimore) 1988;67–154. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Ong RK, Doyle RL. Tropical pulmonary eosinophilia. Chest. 1998;113(6):1673–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.6.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danel C, Israel-Biet D, Costabel U, et al. The clinical role of BAL in rare pulmonary diseases. Eur Respir Rev. 1991;2:83. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshida K, Shijubo N, Koba H, et al. Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia progressing to lung fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 1994;7:1541. doi: 10.1183/09031936.94.07081541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz MI, King TE. Interstitial Lung Disease. 5th Ed. Shelton (CT): People’s Medical Publishing House; 2011: 842.

- 15.Mason RJ, Broaddus VC, Murray JF, Nadel JA. Murray and Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 4th Ed. Philadelphia (PA): Elsevier Saunders; 2005: 1683.

- 16.Pollack CE, Gidengil C, Mehrotra A. The growth of retail clinics and the medical home: two trends in concert or in conflict? Health Aff (Milwood) 2010;29(5):998–1003. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bohmer R. The rise of in-store clinics—threat or opportunity? N Engl J Med. 2007;356(8):765–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rudavsky R, Pollack CE, Mehrotra A. The geographic distribution, ownership, prices, and scope of practice at retail clinics. Ann Int Med. 2009;151(5):315–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-5-200909010-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed A, Fincham JE. Physician office vs retail clinic: patient preferences in care seeking for minor illnesses. Ann Fam Med. 2009;8(2):117–23. doi: 10.1370/afm.1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]