Abstract

Background

Each year in the US approximately 50,000 neonates receive inpatient pharmacotherapy for the treatment of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS).

Objective

To compare the safety and efficacy of a traditional inpatient only approach with a combined inpatient and outpatient methadone treatment program.

Design/Methods

Retrospective review (2007-9). Infants were born to mothers maintained on methadone or buprenorphine in an antenatal substance abuse program. All infants received methadone for NAS treatment as inpatient. Methadone weaning for the traditional group (75 pts) was inpatient while the combined group (46 pts) was outpatient.

Results

Infants in the traditional and combined groups were similar in demographics, obstetrical risk factors, birth weight, GA and the incidence of prematurity (34 & 31%). Hospital stay was shorter in the combined than in the traditional group (13 vs 25d; p < 0.01). Although the duration of treatment was longer for infants in the combined group (37 vs 21d, p<0.01), the cumulative methadone dose was similar (3.6 vs 3.1mg/kg, p 0.42). Follow-up: Information was available for 80% of infants in the traditional and 100% of infants in the combined group. All infants in the combined group were seen ≤ 72 hours from hospital discharge. Breast feeding was more common among infants in the combined group (24 vs. 8% p<0.05). Following discharge there were no differences between the two groups in hospital readmissions for NAS. Prematurity (<37w GA) was the only predictor for hospital readmission for NAS in both groups (p 0.02, OR 5). Average hospital cost for each infant in the combined group was $13,817 less than in the traditional group.

Conclusions

A combined inpatient and outpatient methadone treatment in the management of NAS decreases hospital stay and substantially reduces cost. Additional studies are needed to evaluate the potential long term benefits of the combined approach on infants and their families.

Introduction

Opioid dependence during pregnancy has significant implications for the infant, most notably neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS).1-2 NAS is a constellation of physiological signs and behaviors observed following in utero exposure to opiates.1,3 Among exposed infants, the incidence of NAS ranges from 21 to 94 percent, with about half of the infants requiring some form of pharmacotherapy.4-6

In the United States, the number of drug affected newborns (including opiates) has increased 300 percent since the 1980’s and the health care expenditure in their treatment has been estimated to be as much as 112.6 million dollars per year.2,4 Much of this cost is due to prolonged hospital stays in neonatal intensive care units (NICU).6-7

The benefits of participating in an antenatal drug treatment program include a reduction in drug-seeking behavior, illicit substance abuse, preterm birth, and infant mortality.8-11 Methadone or buprenorphine use for narcotic-abusing women in an antenatal program improves health care utilization and preparation for parenting responsibilities, although some continue to misuse illicit substances.12-13

In clinical practice, NAS is commonly observed among infants born to mothers on methadone or buprenorphine maintenance for opiate addiction.2,14 Traditional strategies for the care of infants with NAS have focused mainly on inpatient management that has led to prolonged hospital stays (i.e. median of 25 days, range of 8-105 days.6,14-17 However, following initial stabilization, many infants with NAS are otherwise healthy and may not require intensive inpatient care.10,12,17,19 Considering that prolonged hospital stays limit opportunities for maternal-infant bonding and consume hospital resources, alternative strategies that reduce unnecessary hospitalization are highly desirable.6,12,20-22 A recent national survey of the management of NAS in the United Kingdom and Ireland revealed that 29% of neonatal units discharge infants’ home on medication.19 Further, other investigators reported no adverse events among infants with NAS administered medication by their caregivers in the community setting.18 However, the paucity of available data on the safety, feasibility, and resources required to care for infants with NAS on an outpatient basis has limited widespread adoption of this approach.

These issues led to the recent development of a multidisciplinary combined inpatient and outpatient treatment program for infants with NAS. An attending physician (CRB) willing to care for these infants as outpatients following initial inpatient stabilization offered this option to mothers in an antepartum substance abuse program. The purpose of this paper is to compare the safety and efficacy of a traditional inpatient only approach versus a combined inpatient and outpatient weaning strategy for infants with NAS.

Methods

This was a retrospective review conducted at The Ohio State University Medical Center (OSUMC) between January 2007 and January 2009. This investigation was approved by the Institutional Review Board. Outpatient (private physician, primary care clinics and emergency room records) were also used.

OSUMC is a tertiary referral center for obstetrics and gynecology, serving a population of approximately 900,000, with over 5000 births per year. We identified 256 infants born to women receiving methadone or buprenorphine as part of an antenatal outpatient treatment program. Of these infants 121 (47%) required treatment for NAS while in the NICU (two thirds) or in the intermediate care nursery (one third). Infants exposed in utero to illicit drugs (i.e. cocaine, heroin etc.) only were excluded. To ensure the validity of the maternal history provided, infants had a meconium or urine toxicology performed at the time of delivery.

Initial inpatient management of NAS

Based on attending physician preference, we have two treatment strategies for infants with NAS at our hospital. We identified 75 infants who received methadone for NAS entirely in the inpatient setting (traditional group) and 46 infants who initially received methadone treatment as inpatients then completed the weaning process in the outpatient setting (combined group). The initial hospital management of infants with NAS was similar between the two groups. Infants born to mothers receiving methadone or buprenorphine were observed for signs and symptoms of withdrawal immediately after feeding using the Finnegan scoring system.3 Methadone (0.05mg/kg every 12 hours) was initiated if the infant achieved 3 scores ≥ 8 or 2 scores ≥ 12 and it was increased until the infant’s average score was <8 over a 24 hour time period. Phenobarbital (10mg/kg loading dose, 5mg/kg per day maintenance dose) was administered as an additional agent if response to methadone was inadequate. Non-pharmacological management, including swaddling, pacifier use, and provision of a quiet environment, was also used for both groups.21

Traditional Group: Inpatient methadone weaning strategy

For infants in the traditional group, methadone was weaned by 5-10 percent per day, with adjustments to the dosing schedule made based on Finnegan scores. Once the infant was successfully weaned off methadone, an additional 3-7 day period of monitoring for withdrawal was completed prior to discharge home. Following discharge infants in the traditional group were seen in primary care clinics and/or at a dedicated NAS clinic (Nationwide Children’s Hospital) where a team of physicians, nurses, social workers, lactation specialists, and physical/occupational therapists were available.

Combined Group: Outpatient methadone weaning strategy

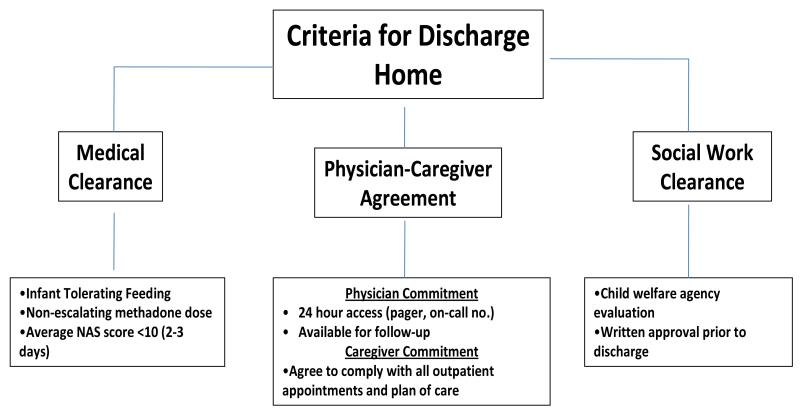

To be included in the combined group infants and caregivers had to fulfill specific medical and social work criteria (Figure 1). As a safeguard, only the amount of methadone needed for 3 days before the infant’s initial outpatient appointment was prescribed. All caregivers underwent intensive instruction on administration of methadone for their infants and were made aware of the symptoms of drug overdose or withdrawal.

Figure 1.

Criteria for discharge home for infants in the inpatient-outpatient (combined) methadone treatment group

Following discharge infants in the combined group were seen in another dedicated outpatient clinic by the same physician (CRB) that provided inpatient care. This clinic is staffed by trained nurses and with ancillary staff (social workers, lactation specialists, and physical/occupational therapists) available for consultation. Caregivers were required to bring their infant to the clinic weekly for general health and state of abstinence evaluation where, according to their needs, methadone was weaned at a rate of 0.05-0.2 mg per week. Conversely, methadone was increased at similar rates if based on the Finnegan score. Methadone was prescribed weekly and dispensed from the hospital pharmacy in sealed, unit dose oral syringes. If the infant was on both phenobarbital and methadone, efforts were made to wean the phenobarbital first.

Considering patterns of referral and proximity (zip code), the assumption was made that if acute care for these infants were needed it would be provided at the only children’s hospital in the county (Nationwide Children’s Hospital). Outpatient and inpatient hospital and clinic records were reviewed to determine whether infants in either group were seen in the emergency room, readmitted to the hospital and/or restarted on inpatient treatment for NAS.

Data Analysis

Comparisons between groups and subgroups of infants with NAS were made with Chi-square, Fisher’s, and t-test. To evaluate the independent relationship between variables that may be associated with readmission to hospital for NAS, a multiple linear regression model was constructed using the following variables: treatment group, maternal methadone dose, highest NAS score, need for phenobarbital, and prematurity (< 37 weeks). Gestational ages were rounded to the closest completed week. When available, data was presented as mean ± SD.

Results

Of 69 mother-infant dyads evaluated for possible inclusion in the combined group, 46 (67%) met all medical and social work criteria for outpatient methadone weaning. The 23 who did not meet criteria were included in the traditional group that then comprised 75 mother-infant dyads. Mothers in these two groups were similar in demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1). Of these, 96% of the mothers were Caucasion, 2% African American and 2% Hispanic. Smoking, hepatitis B and hepatitis C infections occurred with similar frequency in both groups. Employment status and level of education were similar between the two groups.

Table 1.

Maternal Characteristics

| Traditional | Combined | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients no. | 75 | 46 | |

| Maternal age (years) | 26 ± 4a | 26 ± 4 | NS |

| Primigravida no. (%) | 11 (15) | 10 (22) | NS |

| Cesarean delivery no. (%) | 24 (32) | 8 (17) | <0.05 |

| Smoking no. (%) | 55 (73) | 36 (78) | NS |

| Hepatitis B no. (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | NS |

| Hepatitis C no. (%) | 17 (23) | 10 (22) | NS |

| Breast feeding no. (%) | 6 (8) | 11 (24) | <0.01 |

| Methadone alone no. (%) | 48 (64) | 29 (63) | NS |

| Methadone and THCb no. (%) | 12 (16) | 11 (24) | NS |

| Methadone and illicit drugsc no. (%) | 15 (20) | 6 (13) | NS |

| Buprenorphine alone no. (%) | 4 (67) | 4 (80) | NS |

| Buprenorphine and THC no. (%) | 1 (17) | 1 (20) | NS |

| Buprenorphine and illicit drugs no. (%) | 1 (17) | 0 | NS |

| ≥ High School Diploma no. (%) | 42 (56) | 19 (41) | NS |

| Unemployed no. (%) | 65 (87) | 38 (83) | NS |

= Mean ± SD

= THC (Tetrahydrocannabinol)

= Illicit drugs (cocaine, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, heroine)

At the time of delivery 92% of the mothers in the traditional and 89% in the combined group were receiving methadone. The remaining mothers in each group were on buprenorphine. Dosages of maternal methadone (median 80mg/d, range 20-180mg/d) and buprenorphine (median 6mg/tid, range 2-8mg/tid) were similar between the two groups. By history or urine toxicology, illicit drugs were noted in 20 and 13 percent of mothers in the traditional and combined groups, respectively (Table 1).

Neonatal Outcomes

Neonatal outcomes for the 75 infants in the traditional and the 46 infants in the combined group are presented in Table 2. The two groups were similar in birth weight, gestational age, rate of prematurity, and the caregiver at the time of discharge (72% with mothers or family relatives, 28% with child welfare agencies. The number of infants exclusively breastfed or breast fed with supplementation (>50% breast milk) was higher in the combined group (24% vs 8%, p <0.05).

Table 2.

Neonatal Outcomes

| Traditional | Combined | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infants no. | 75 | 46 | |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 37 ± 3a | 38 ± 2 | NS |

| 34-36 6/7 weeks gestation no. (%) | 26 (34) | 14 (31) | NS |

| >37 weeks gestation no. (%) | 49 (66) | 30 (69) | NS |

| Males no. (%) | 33 (44) | 20 (43) | NS |

| Birth weight (g) | 2677 ± 580 | 2858 ± 426 | NS |

| Discharge weight (g) | 3156 ± 634 | 3012 ±470 | NS |

| Highest NASb score | 13 ± 3 | 13 ± 4 | NS |

| Peak NAS score (day) | 3 ± 2 | 3 ± 3 | NS |

| Hospital stay (days) | 25 ± 15 | 13 ± 5 | <0.01 |

| Methadone treatment (days) | 21 ± 14 | 37 ± 20 | <0.01 |

| Cumulative methadone dose (mg/kg) | 3.1 ± 5 | 3.6 ± 3 | NS |

| Pts also on phenobarbital no. (%) | 18 (24) | 13 (28) | NS |

| Phenobarbital treatment (days) | 14 ± 11 | 19 ± 14 | NS |

= Mean ± SD

= Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome

Duration of Hospitalization and Treatment

The overall length of hospital stay was 25 ± 15d for the traditional and 13 ± 5d for the combined (p<0.001). Although the duration of methadone treatment was longer for infants in the combined group (37 ± 20d vs 21 ± 14d, p< 0.001), the cumulative methadone dosage was similar (3.6 ± 3mg/kg vs 3.1 ± 5mg/kg, p 0.42). A similar number of infants in both groups required inpatient phenobarbital to control NAS symptoms (28% in combined and 24% in traditional group). Although 7 of 46 (15%) infants in the combined group required outpatient phenobarbital, there were no differences in the total duration of phenobarbital therapy between the two groups (combined 19 ± 14d vs traditional 14 ± 11d vs, p 0.28).

Outpatient follow-up

Follow-up information for at least 3 months was available in 80 percent of infants in the traditional and 100 percent of infants in the combined group. All infants in the combined group were seen within 72 hours of hospital discharge. No families were lost to follow-up while the infant was receiving outpatient medication for NAS. In the combined group, 13 (17%) required an increase in the methadone dosage for NAS symptoms. Not surprisingly, the continued need to refill prescriptions led to a higher number of primary care patient visits (first 3 months) in the combined group (9 versus 4, p <0.05). Twelve month follow-up data were available in 52 percent of the traditional and 80 percent of the combined group. No infant deaths were noted during the duration of the study. Two infants in the combined group were referred to child protective service for concerns regarding infant neglect or abuse.

Among patients with follow-up data available, the number of emergency room visits per patient for NAS-related symptoms (protracted diarrhea, weight loss, possible seizures) was similar between the two groups (11% traditional, 11% combined). Readmission to the reference hospital for NAS symptoms was also similar between the two groups (5% traditional and 7% combined). There were no differences in the proportion of infants in either group that required restarting in-patient medication for treatment of severe NAS symptoms (4% traditional, 5% combined). Based on the multivariate regression model, the only variable to predict hospital readmission for NAS in the first 3 months of life was prematurity (<37 weeks). We found that maternal methadone dose, infant group, highest NAS score, or need for phenobarbital therapy did not increase the risk for hospital readmission.

The average hospital cost per infant was $27,546 for those in the traditional group and $13,729 for those in the combined group. Treatment in the combined approach resulted in a reduction of in-hospital costs of $635,582 over the two years in review.

Discussion

Traditional management of infants with NAS has focused primarily on inpatient care strategies leading to prolonged hospitalization and extended separation of infants from their primary caregivers.14,17 However, following initial inpatient stabilization, infants with NAS are typically healthy and may not require hospital based care. 10,18-19 This has led to interest in developing community based strategies in the care of infants with NAS. 6,20-22 Concern regarding the stability of the home environment and ability of drug abusing caregivers to adequately comply with outpatient requirements has limited widespread adoption of this approach.23

We have shown that a combined inpatient and outpatient treatment program resulted in a 48 percent reduction in length of hospitalization compared to infants managed with a traditional inpatient approach. Importantly, we found no increased risk of short-term adverse outcomes, emergency room visits, hospital readmission, and need for inpatient treatment for NAS. Infants in the combined group were exposed to a longer course of methadone treatment. However, the cumulative dose of methadone was similar between the two groups. Given that opiates or other medications for NAS may adversely affect development, the fact that infants in both groups were exposed to similar cumulative doses is noteworthy.24-26

It is known that drug-abusing caregivers have poor compliance with outpatient appointments.27 In that regard, the retention rate seen among mother-infant dyads in the combined program is significant and warrants explanation. A single, dedicated physician (CRB) who provided both inpatient and outpatient care was able to establish a long-term relationship with these families. As noted before, extended monitoring of infant growth and neurodevelopment, together with routine assessment of caregiver-infant interactions, are paramount.24-25 Also, the outpatient clinic was able to meet the primary care needs of the infant (vaccinations, referrals, routine well-visits, sick visits). Providing this comprehensive care in a non-threatening, non-punitive, supportive environment likely contributed to better compliance.28

Success of the outpatient program is largely dependent upon patient selection. The combined approach was only offered to mothers enrolled in an antenatal drug treatment program on methadone or buprenorphine. Furthermore, only those who met all social and medical work criteria were included. Considering that most NAS symptoms occur during the first 7 days following delivery, it is imperative that infants be monitored in the hospital throughout this time.29 This approach offers the opportunity to individualize medication dosages, evaluate the stability of the home environment and motivation of the caregiver.23 It is possible that some infants in the combined group had subclinical withdrawal. However, this has also been known to occur among infants managed entirely as inpatient.27 This underscores the need for close outpatient follow-up among infants with NAS regardless of the treatment approach used.17

We recognize that providing access to any opioid may place the caregiver at risk for relapse.23 However, the amount of methadone provided to these infants at any given visit seldom exceeded 0.2 mg/kg per syringe per day compared to an average maternal dose of 80mg per day (range 20-180mg).

We found that preterm infants were five times more likely to be readmitted for NAS than term counterparts. Previous studies have shown that these patients are less likely than term infants to show classic signs of NAS exposure, and many exhibit withdrawal symptoms later than term counterparts.30 Additionally, current NAS scoring systems may not have the sensitivity to detect subtle manifestations of withdrawal in the preterm infant.17

The American Academy of Pediatrics encourages breastfeeding for mothers on methadone noting that, irrespective of its dosage, the transfer of methadone into human milk is minimal.31 Also, recent evidence suggests that breastfeeding for mothers’ on buprenorphine is safe for the infant.32 Considering that breastfeeding has been shown to improve maternal-infant bonding, increase maternal self-esteem, minimize NAS symptoms, and decrease the need for NAS treatment, the higher incidence of this practice in the combined group is encouraging. 17,33-34

Not surprisingly, infants in the combined group had a significant reduction in inpatient cost ($13,817/infant), with an estimated savings of over $635,000 in a two year period. However, developing and maintaining an outpatient (“combined”) strategy requires an investment in health care resources difficult to quantify.35

The main limitations of our study are the retrospective design and small study population. Additionally, the applicability of our findings to a wider range of NAS populations is limited because we included only “motivated” mothers enrolled in an antenatal substance program on methadone or buprenorphine who were further screened for potential compliance with the outpatient strategy. Furthermore, we agree with investigators that reducing hospital length of stay alone in this population is not the primary objective.23 However, our effort to reduce unnecessary hospitalization among this vulnerable infant-caregiver dyad highlights the need for continued investigation of the combined strategy. Continued studies that delineate subpopulations of infants with NAS, and select treatment strategies based on those distinctions, are needed.17

Conclusion

A combined inpatient and outpatient methadone treatment for infants with NAS decreases hospital stay and substantially reduces cost without short-term adverse outcomes. Additional studies are needed to evaluate the applicability of this strategy and to evaluate its potential long-term benefits on infants and their families.

Contributor Information

Carl H. Backes, Clinical Instructor, College of Medicine, The Ohio State University.

Carl R. Backes, Professor of Pediatrics, College of Osteopathic Medicine, Ohio University.

Debra Gardner, Assistant Professor of Pharmacy, College of Pharmacy, The Ohio State University.

Craig A. Nankervis, Associate Professor of Pediatrics, College of Medicine, The Ohio State University.

Peter J. Giannone, Associate Professor of Pediatrics, College of Medicine, The Ohio State University.

Leandro Cordero, Professor of Pediatrics and Obstetrics, College of Medicine, The Ohio State University.

References

- 1.Kuschel C. Managing drug withdrawal in the newborn infant. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2007;12:127–33. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones H, Kaltenbach K, Heil SH, Stine SM, Coyle MG, Arria AM, et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome after methadone or buprenorphine exposure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2320–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finnegan LP, Connaughton JF, Jr, Kron RE, Emich JP. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: assessment and management. Addict Dis. 1975;2:141–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Drugs Neonatal Drug Withdrawal. Pediatrics. 1998;101:1079–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ebner N, Rohrmeister K, Winklbaur B, Baewert A, Jagsch R, Peternell A, et al. Management of neonatal abstinence syndrome in neonates born to opioid maintained women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:131–38. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dryden C, Young D, Hepburn M, Mactier H. Maternal methadone use in pregnancy: Factors associated with the development of neonatal abstinence syndrome and implications for healthcare resources. BJOG. 2009;116:665–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Svikis CS, Golden AS, Huggins GR, Pickens RW, McCaul ME, Velez ML, et al. Cost-effectiveness of treatment for drug-abusing pregnant women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;45:105–13. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hulse GK, Milne E, English DR, Holman CDJ. Assessing the relationship between maternal opiate use and neonatal mortality. Addiction. 1998;93:1033–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93710338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arlettaz R, Kashiwagi M, Das-Kundu S, Fauchere J, Lang A, Bucher HU. Methadone maintenance program in pregnancy in a Swiss perinatal center (II): neonatal outcome and social resources. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2005;84:145–50. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns L, Mattick RP, Lim K, Wallace C. Methadone in pregnancy: treament retention and neonatal outcomes. Addiction. 2007;102:264–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD002209. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002209.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson K, Gerada C, Greenough A. Substance misuse during pregnancy. Brit J Psych. 2003;183:187–89. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.3.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunt RW, Tzioumi D, Collins E, Jeffery HE. Adverse neurodevelopmental outcome of infants exposed to opiate in-utero. Early Hum Dev. 2008;84:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCarthy JJ, Leamon MH, Parr MS, Anania B. High dose methadone maintenance in pregnancy: Maternal and neonatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:606–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lainwala S, Brown ER, Weinschenk NP, Blackwell MT, Hagadorn JI. A retrospective study of length of hospital stay in infants treated for neonatal abstinence syndrome with methadone versus oral morphine preparations. Adv Neonatal Care. 2005;5:265–72. doi: 10.1016/j.adnc.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langenfeld S, Birkenfeld L, Herkenrath P, Müller C, Hellmich M, Theisohn M. Therapy of the neonatal abstinence syndrome with tincture of opium or morphine drops. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isemann B, Meinzen-Derr J, Akinibi H. Maternal and neonatal factors impacting response to methadone therapy in infants treated for neonatal abstinence syndrome. J Perinatol. 2011;31:25–29. doi: 10.1038/jp.2010.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oei J, Feller JM, Lui K. Coordinated outpatient care of the narcotic-dependent infant. J Paediatr Child Health. 2001;37:266–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2001.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Grady MJ, Hopewell J, White MJ. Management of neonatal abstinence syndrome: A national survey and review of practice. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;94:F249–52. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.152769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abrahams RR, Kelly SA, Payne S, Thiessen PN, Mackintosh J, Janssen PA. Rooming-in compared with standard care for newborns of mothers using methadone or heroin. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53:1722–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Velez M, Jansson LM. The opioid dependent mother and newborn dyad: non-pharmacologic care. J Addict Med. 2008;2:113–20. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31817e6105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saiki T, Lee S, Hannam S, Greenough A. Neonatal abstinence syndrome – postnatal ward versus neonatal unit management. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:95–98. doi: 10.1007/s00431-009-0994-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jansson LM, Velez M, Harrow C. The opioid exposed newborn: Assessment and pharmacologic management. J Opioid Manag. 2009;5:47–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chasnoff I, Burns W. The moro reaction: a scoring system for neonatal narcotic withdrawal. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1984;26:484–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1984.tb04475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chasnoff IJ. Newborn infants with drug withdrawal smptoms. Pediatr Rev. 1988;9:273–77. doi: 10.1542/pir.9-9-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Phenobarbital for the treatment of epilepsy in the 21st century: A critical review. Epilepsia. 2004;45:1141–49. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.12704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soepatmi S. Developmental outcomes of children of mothers dependent on heroin or heroin/methadone during pregnancy. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1994;404:36–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selleck CS, Redding BA. Knowledge and attitudes of registered nurses toward perinatal substance abuse. JOGNN. 1988;27:70–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1998.tb02593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serane VT, Kurian O. Neonatal abstinence syndrome. Indian J Pediatr. 2008;75:911–14. doi: 10.1007/s12098-008-0107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doberczak TM, Kandall SR, Wilets I. Neonatal opiate abstinence syndrome in term and preterm infants. J Pediatr. 1991;118:933–37. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)82214-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Drugs The transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics. 2001;108:776–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson RE, Jones HE, Fischer G. Use of buprenorphine in pregnancy: Patient management and effects on the neonate. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70:S87–S101. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdel-Latif ME, Pinner J, Clews S, Cook F, Lui K, Oei J. Effects of breast milk on the severity and outcome of neonatal abstinence syndrome among infants of drug-dependent mothers. Pediatrics. 2005;117:e1163–e1169. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jansson LM, Choo R, Velez ML, Harrow C, Schroeder JR, Shakleya DM, et al. Methadone maintenance and breastfeeding in the neonatal period. Pediatrics. 2008;121:106–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jackson L, Ting A, Mckay S, Galea P, Skeoch C. A randomised controlled trial of morphine versus phenobarbitone for neonatal abstinence syndrome. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004;39:F300–F304. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.033555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]