Abstract

Objective: The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of a zinc-substituted nano-hydroxyapatite (Zn-HA) coating, applied by an electrochemical process, on implant osseointegraton in a rabbit model. Methods: A Zn-HA coating or an HA coating was deposited using an electrochemical process. Surface morphology was examined using field-emission scanning electron microscopy. The crystal structure and chemical composition of the coatings were examined using an X-ray diffractometer (XRD) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). A total of 78 implants were inserted into femurs and tibias of rabbits. After two, four, and eight weeks, femurs and tibias were retrieved and prepared for histomorphometric evaluation and removal torque (RTQ) tests. Results: Rod-like HA crystals appeared on both implant surfaces. The dimensions of the Zn-HA crystals seemed to be smaller than those of HA. XRD patterns showed that the peaks of both coatings matched well with standard HA patterns. FTIR spectra showed that both coatings consisted of HA crystals. The Zn-HA coating significantly improved the bone area within all threads after four and eight weeks (P<0.05), the bone to implant contact (BIC) at four weeks (P<0.05), and RTQ values after four and eight weeks (P<0.05). Conclusions: The study showed that an electrochemically deposited Zn-HA coating has potential for improving bone integration with an implant surface.

Keywords: Zinc, Hydroxyapatite coating, Electrochemical process, Osseointegration, Implant

1. Introduction

As a natural bone mineral, hydroxyapatite (HA) is used as a coating on implant surfaces to improve bone integration with implants (Porter et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2010a; 2010b). Currently, HA coatings are applied to implant surfaces commercially using plasma sprays (Herman, 1988; Ong and Chan, 2000). However, these coatings have some drawbacks: they can be too thick; it can be difficult to deposit them on porous surfaces; they may have poor crystal structure; and there may be poor adhesion between the HA and the implants. Therefore, numerous other deposition processes have been studied (Ellies et al., 1992; Palka et al., 1998).

Investigations have shown that nano-HA has specific properties that may affect cell activity and enhance bone response (Guo et al., 2007; Sato et al., 2008). Moreover, the similarity of its chemistry and topography to those of natural HA crystals improves osteoblast response (Ong et al., 1998). Thus, the size and morphology of HA crystals deposited onto implant surfaces should approximate those of HA in natural bone tissue. Our previous studies indicated that an electrochemical deposition process could form nano-HA similar to HA found in bone tissue, which is rod-like with a hexagonal cross section and a diameter of about 70–80 nm. In vivo experiments showed that this HA coating improved implant osseointegration (He et al., 2009).

Zinc (Zn) is an essential trace element in the human body and has a stimulatory effect on bone metabolism (Rossi et al., 2001). Zn deficiency results in skeletal changes, including retardation of skeletal growth (Barceloux, 1999), prolonged bone recovery (Hosea et al., 2004), reduced premenopausal bone mass (Angus et al., 1988), and postmenopausal osteoporosis (Herzberg et al., 1990). Bone formation and mineralization are also improved by Zn (Hall et al., 1999), which stimulates collagen production and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity, increases bone formation and mineralization, and decreases bone resorption.

In an earlier study, we applied Zn to a nano-HA coating to improve its bioactivity. Zn presented in the Zn-substituted nano-HA (Zn-HA) coating at a molar ratio of 1.04%, and enhanced the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts (Yang et al., 2012). The aim of the current study was to investigate the effects of a Zn-HA coating on implant osseointegration in a rabbit model.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Design and surface treatment of implants

In this study, we used screw-shaped titanium implants with a diameter of 3.0 mm, length of 10 mm, thread space of 0.7 mm, and thread depth of 0.35 mm. Implants were polished by sandblasting with green silicon carbide. Subsequently, HF/HNO3 and HCl/H2SO4 solutions were in turn used to treat the implants (Yang et al., 2008).

2.2. Deposition of HA and Zn-HA coatings

Deposition of HA coatings was performed according to Yang et al. (2009a; 2010a; 2010b). The implants formed the cathode electrode and the counter electrode was a platinum (Pt) plate. Ca(NO3)2 (1.2 mmol/L) and NH4H2PO4 (0.72 mmol/L) were dissolved in the electrolytes. The Ca/P ratio was 1.67. To increase the conductivity, NaNO3 (0.1 mol/L) was added. A direct current (DC) power source was used at 3.0 V at 85 °C for 30 min. For deposition of the Zn-HA coatings, there was Zn(NO3)2 in the electrolyte solution. The Zn/(Ca+Zn) molar ratio was 10%.

2.3. Surface analysis

Field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FSEM; FEI, SIRION100) was used to examine the surface morphology of the porous surface of the HA and Zn-HA coatings. An X-ray diffractometer (XRD; Philips XD-98) with Cu Kα radiation was used to determine the crystal structure. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), using the KBr pellet technique, was used for spectroscopic analysis of the grown CaP microcrystals.

2.4. Experimental design and implant surgery

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhejiang University approved the experiment. Adult white rabbits weighing 2.5–3.0 kg were used. Implants were inserted into femurs as described by Nkenke et al. (2002). Briefly, bilateral femurs of 15 rabbits received a total of 30 implants (one per femur). SuMianXin II (0.1–0.2 ml/kg, intramuscularly (i.m.); the Military Veterinary Institute, Quartermaster University of PLA, Changchun, China) was used for general anesthesia. Lidocaine was used for local administration. The implant site was the distal aspect of the femur. Test implants were inserted in the left femurs and control implants in the right femurs. A hole with a diameter of 3.0 mm was prepared. Implants were placed into the hole. After implantation, antibiotic (penicillin, 400 000 U/d) was administered for 3 d.

A total of 48 implants were placed into tibias (one per tibia), similar to the number used by Suh et al. (2007). In brief, the implant sites were the medial surfaces of the tibias. A hole with a diameter of 3.0 mm was prepared. A control implant and a test implant were inserted in each animal.

After two, four, and eight weeks, an overdose of SuMianXin (1.0 ml, i.m.) was given to the animals. Tissues were retrieved and prepared for histomorphometric evaluation and removal torque (RTQ) tests.

2.5. RTQ tests

RTQ tests were performed according to Suh et al. (2007), Szmukler-Moncler et al. (2004), and Yang et al. (2009b). Femurs containing the implants were retrieved by segmental osteotomy. Tests were performed immediately. Saline-soaked gauze was applied to keep the femurs moist. A portable digital torque meter (BS30, Ningbo Yinuo Scientific Equipment, Ltd., China) was applied to test the reverse torque at each implant. Samples were placed on a desk. The tie-in of the sensor was placed into the implants. A torque was slowly applied vertical to the implant long axis. The peak torque was recorded as the value at which the implant loosened, which indicated the bonding strength between the implant and the bone tissue.

2.6. Specimen preparation and histomorphometric evaluation

Tibia samples were chosen for histomorphometric evaluation. The samples were fixed in 4% neutral-buffered formaldehyde, dehydrated using alcohols, and embedded in methyl methacrylate for undecalcified sectioning. The central part of each implant was used to prepare an undecalcified cut and ground section using a macro cutting and grinding system (Exakt 310 CP series; Exakt Apparatebau, Norderstedt, Germany). The final thickness was 30 μm. Stevenel’s blue and van Gieson’s picro fuchsin were used for staining. Light microscopy (BX51, Olympus, Japan) and a PC-based image analysis system (Image-Pro Plus, Media Cybernetics, Silver Springs, MD, USA) were applied to perform histomorphometric analysis. There were two parameters: the bone to implant contact (BIC) in the threads and the bone area inside the same threads. The BIC was measured as the percentage of the length of bone in direct contact with the implant surface. The bone area was measured as the bone area in the threads as a percentage of the total area of the implant threads.

2.7. Statistical analysis

The RTQ values and histomorphometric data were statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics 19.0 (SPSS, USA). The Mann-Whitney U test was applied to compare the parameters. A P value <0.05 was considered significant. For comparison of more than two unrelated variables, a Kruskal-Wallis test was used to test differences. If appropriate, a Bonferroni correction was used for multiple testing.

3. Results

3.1. Surface analysis

Multilevel porous structures were seen in sandblasted and etched implant surfaces (Fig. 1). Rod-like HA crystals appeared on both types of implant surfaces (Fig. 2). The direction of crystal growth was perpendicular to the implant surfaces. The general morphology of the HA coating was influenced by the addition of Zn. Compared to cross sections of HA crystals, the hexagons of Zn-HA crystals were irregular or even absent. HA coatings seemed to be bigger than Zn-HA coatings.

Fig. 1.

FSEM micrograph of porous implant surface after sandblasting and etching

Fig. 2.

FSEM micrographs of HA (a, c) and Zn-HA (b, d) coated surfaces

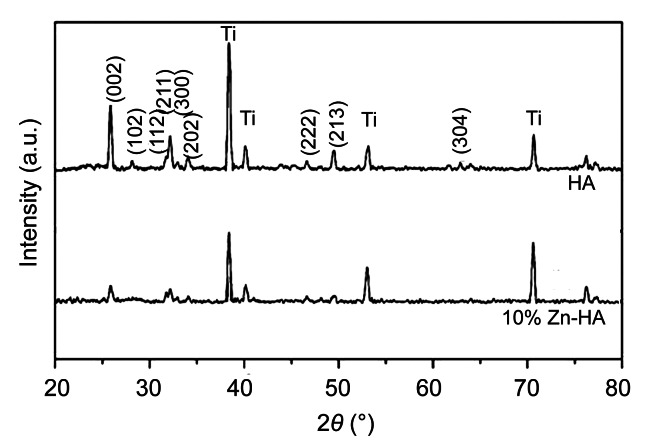

The XRD pattern of both coatings showed typical apatite peaks at 2θ of 25.9° and 31°–33° (Fig. 3). The peaks of the coatings match well with those of standard HA patterns.

Fig. 3.

XRD patterns of HA and Zn-HA coatings

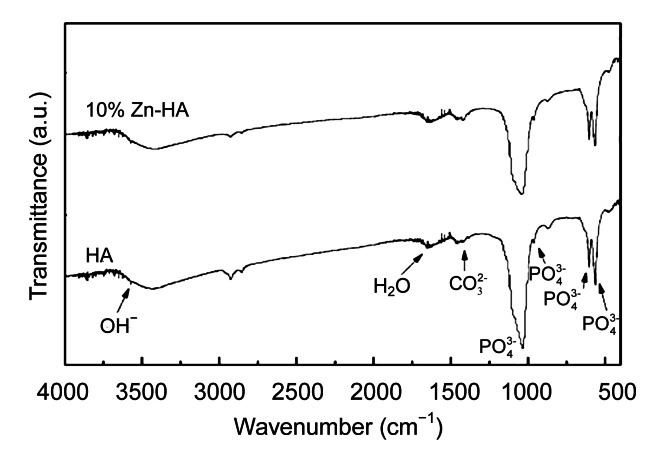

FTIR spectra showed that the chemical composition of both coatings was HA (Fig. 4). The stretching mode of the OH– group appears at 1 651 and 3 572 cm−1. The bands that correspond to the internal modes of the PO4 3− group occur at ν 2 (600 and 570 cm−1) and ν 1 (1 085 and 1 033 cm−1). The OH– stretching band of 3 572 cm−1 is considered as confirming the identification of HA structure.

Fig. 4.

FTIR spectra of HA and Zn-HA coatings

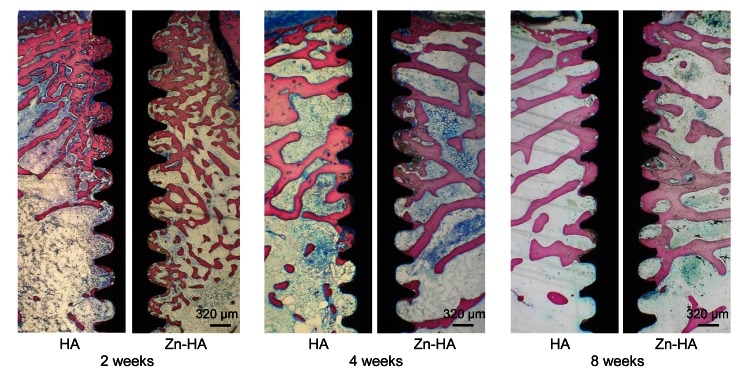

3.2. Histological observation

After two weeks, there were no evident differences in histological behavior between the two groups. New bone was formed on and along implant surfaces. Within the circumference of marrow cavities of cortical bone, there were osteoblast-like cells, suggesting the beginning of new bone formation. There was new bone tissue on implant surfaces in the marrow space. Bone-implant contact was extensive along implant surfaces. After four and eight weeks, bone tissue appeared on both types of implant surfaces. Marrow cavities were sparse in new bone, indicating the maturation of the new bone. However, there was more bone tissue inside the threads of Zn-HA-coated implants than in those of HA-coated implants (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Histological sections of HA and Zn-HA coatings after two, four, and eight weeks

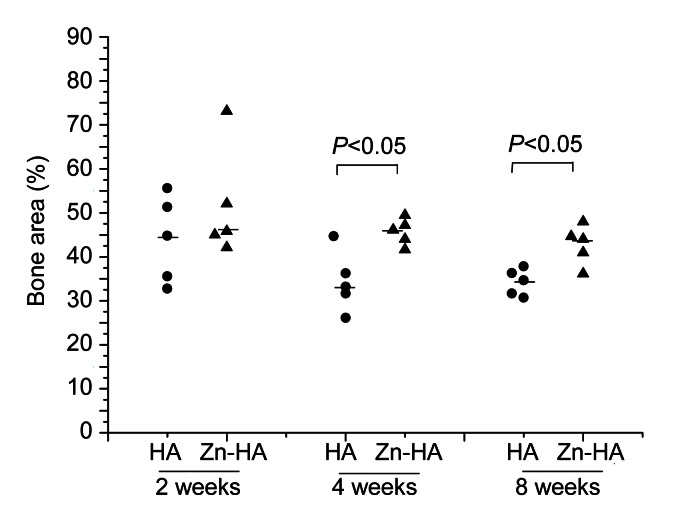

3.3. Histometric analysis

The percentage bone area within all threads is shown in Fig. 6. At two weeks, there were no significant differences between the two groups (P=0.347). However, there were differences at four and eight weeks (P=0.028 and P=0.028, respectively). No significant differences appeared in bone area within all threads among the three time points for both groups (P=0.181 for the HA-coated group, and P=0.249 for the Zn-HA-coated group).

Fig. 6.

Percentage bone area within all threads of HA-coated and Zn-HA-coated implants for each time point

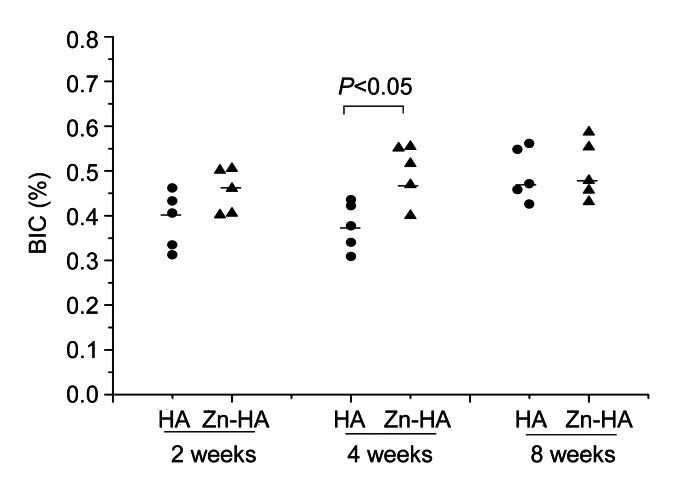

The percentage BIC for each time point is shown in Fig. 7. The Zn-HA-coated group had significantly higher BIC at four weeks (P=0.028). No differences were found between the two groups at two and eight weeks (P=0.251 and P=0.754, respectively). Among the three time points, no differences were found within the Zn-HA-coated group (P=0.472), but significant differences were found within the HA-coated group (P=0.034). In the HA-coated group, there were clear differences between the observations at two and eight weeks (P=0.011) and between the obsevations at four and eight weeks (P=0.005), but no differences were found between the observations at two and four weeks (P=1.000).

Fig. 7.

Percentage BIC of HA-coated and Zn-HA-coated implants for each time point

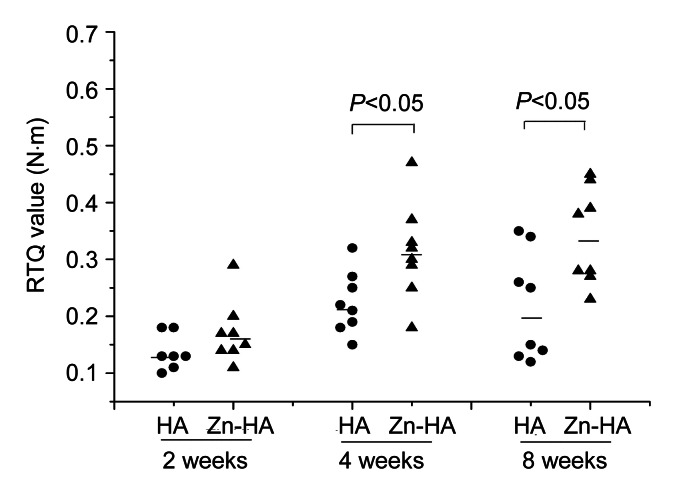

3.4. RTQ tests

Details of the RTQ values of both implants (n=48) are given in Fig. 8. There were no differences between the two groups at two weeks (P=0.266). The Zn-HA-coated implants showed significantly greater RTQ values than the HA-coated implants after four and eight weeks (P=0.031 and P=0.021, respectively).

Fig. 8.

Detailed RTQ values of HA-coated and Zn-HA-coated implants for each time point

Significant differences appeared in bone area within all threads among the three time points for both groups (P=0.023 for the HA-coated group, and P=0.002 for the Zn-HA-coated group). For the HA-coated group, there were clear differences between the observations at two and four weeks (P=0.037), but no differences were found between the observations at two and eight weeks (P=0.069) or between the observations at four and eight weeks (P=1.000). For the Zn-HA-coated group, there were clear differences between the observations at two and four weeks (P=0.009) and between the observations at two and eight weeks (P=0.004). No differences were found between the observations at four and eight weeks (P=1.000).

4. Discussion

In this study, an electrochemical procedure was applied to deposit a thin Zn-HA coating onto porous surfaces. The results indicated that this coating improved BIC, the formation of new bone tissue, and the bonding strength of the implant with bone tissue after four and eight weeks.

The results are similar to those of previous papers. Alvarez et al. (2010) demonstrated that implants treated with a solution containing [Zn(OH)4]2− complex showed increased bone fixation compared with control groups. A Zn-containing α-tricalcium phosphate (αZnTCP) was shown to promote new bone formation (Li et al., 2009). Fluoridated hydroxyapatite (FHA) coatings with incorporated Zn ions improve cell viability and new bone formation (Miao et al., 2011). However, although Zn-Ca phosphate coatings have a positive effect on bone formation, a study by Kawamura et al. (2003) showed that they may increase bone resorption at later stages. This may have been caused by the high Zn concentration in the coating and the implant method used in that study.

Although the bone metabolism mechanisms of Zn remain to be fully elucidated, Zn ions play a major role in increased implant osseointegration. Zn has a positive effect on the preservation of bone mass by improving osteoblast function and inhibiting osteoclastic function. Collagen I, osteocalcin (OC), ALP, and bone sialoprotein (BSP) expressions are improved by Zn. Zn may play a major role in osteoblast mineralization through intra- and extra-cellular Zn movements involving Zn storage proteins and transporters (Nagata and Lonnerdal, 2011). As for osteoblasts, Zn reduces interleukin-6 (IL-6), a potent bone resorptive agent which increases osteoclast formation and stimulates osteoclast activity to resorb bone at the bone implant interface (Hatakeyama et al., 2002). These may be the main reason for the high BIC, increased bone area, and improved bone bonding strength observed following Zn-HA coating. Future investigations will aim to determine the precise mechanisms of Zn metabolism in bone.

Dissolution of HA also played a role in the improved implant osseointegration as shown by the Zn-HA coating. HA dissolution could release Zn ions, Ca, and phosphorus from the coating, thereby increasing the concentration of these ions around implant surfaces. These ions all improve osteoblast function and new bone formation. Moreover, it is important in the bone bonding of crystalline HA to transit from crystalline to amorphous HA. This occurs by a dissolution-precipitation process: (1) transformation of crystalline HA into amorphous HA; (2) over-saturation formation of Ca and phosphorus; and (3) precipitation of the nanocrystallites from the oversaturated solution in the presence of collagen fibres (Meirelles et al., 2008). In the Zn-HA coating, a portion of Ca2+ is replaced by Zn2+, which results in improved dissolution of the Zn-HA coating. Therefore, the high dissolution of the Zn-HA coating facilitates ingrowth of bone into the implant surfaces.

There were no clear differences between implant types in bone area, BIC, or RTQ values at the observation of two weeks. Surface morphology and chemical structures play a role in implant osseointegration (Davies, 1998; 2000; Schenk and Buser, 1998). The two implant surfaces had a similar ability to improve the formation of new bone in the early stages of implantation. After eight weeks of implantation, no differences were found in BIC between the two implants. But the Zn-HA coating clearly improved bone area within the threads of the implant. Therefore, significant differences were found in RTQ values between the two implants.

An electrochemical technique was applied to deposit the Zn-HA coating on the implant surfaces. This technique did not destroy the porous surface of the implant during the preparation of the HA coating. The porous morphology of the implant surface was still clear because the coating was very thin. Moreover, the rod-like HA was similar to HA in bone tissue, making it well-suited for bone integration with implant surfaces. Therefore, this Zn-HA coating appears to be favorable for clinical development, although the preparation parameters need further study.

5. Conclusions

The present study has shown that an electrochemically deposited Zn-HA coating has potential benefits for improving bone integration with implant surfaces.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Zhejiang Guangci Medical Appliance Company (China) for the experimental implants and disks.

Footnotes

Project supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81000462) and the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. R2110374), China

Compliance with ethics guidelines: Shi-fang ZHAO, Wen-jing DONG, Qiao-hong JIANG, Fu-ming HE, Xiao-xiang WANG, and Guo-li YANG declare that they have no conflict of interest.

All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed.

References

- 1.Alvarez K, Fukuda M, Yamamoto O. Titanium implants after alkali heating treatment with a [Zn(OH)4]2− complex: analysis of interfacial bond strength using push-out tests. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2010;12(s1):e114–e125. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8208.2010.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus RM, Sambrook PN, Pocock NA, Eisman JA. Dietary intake and bone mineral density. Bone Miner. 1988;4(3):265–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barceloux DG. Zinc. Clin Toxicol. 1999;37(2):279–292. doi: 10.1081/CLT-100102426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies JE. Mechanisms of endosseous integration. Int J Prosthodont. 1998;11(5):391–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies JE. Understanding peri-implant endosseous healing. J Dent Educ. 2000;67(8):932–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellies LG, Nelson DG, Featherstone JD. Crystallographic changes in calcium phosphates during plasma-spraying. Biomaterials. 1992;13(5):313–316. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(92)90055-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo X, Gough JE, Xiao P, Liu J, Shen Z. Fabrication of nanostructured hydroxyapatite and analysis of human osteoblastic cellular response. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;82(4):1022–1032. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall SL, Dimai HP, Farley JR. Effects of zinc on human skeletal alkaline phosphatase activity in vitro. Calcif Tissue Int. 1999;64(2):163–172. doi: 10.1007/s002239900597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatakeyama D, Kozawa O, Otsuka T, Shibata T, Uematsu T. Zinc suppresses IL-6 synthesis by prostaglandin F2α in osteoblasts: inhibition of phospholipase C and phospholipase D. J Cell Biochem. 2002;85(3):621–628. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He FM, Yang GL, Wang XX, Zhao SF. Effect of electrochemically deposited nano-hydroxyapatite on bone-bonding of sandblasted-dual acid etched titanium implant. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2009;24(5):790–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herman H. Plasma spraydeposition processes. MRS Bull. 1988;12:60–67. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herzberg M, Foldes J, Steinberg R, Menczel J. Zinc excretion in osteoporotic women. J Bone Miner Res. 1990;5(3):251–257. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650050308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosea HJ, Taylor CG, Wood T, Mollard R, Weiler HA. Zinc-deficient rats have more limited bone recovery during repletion than diet-restricted rats. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2004;229(4):303–311. doi: 10.1177/153537020422900404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawamura H, Ito A, Muramatsu T, Miyakawa S, Ochiai N, Tateishi T. Long-term implantation of zinc-releasing calcium phosphate ceramics in rabbit femora. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;65(4):468–474. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li X, Sogo Y, Ito A, Mutsuzaki H, Ochiai N, Kobayashi T, Nakamura S, Yamashita K, Legeros RZ. The optimum zinc content in set calcium phosphate cement for promoting bone formation in vivo. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2009;29(3):969–975. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meirelles L, Albrektsson T, Kjellin P, Arvidsson A, Franke SV, Andersson M, Currie F, Wennerberg A. Bone reaction to nano hydroxyapatite modified titanium implants placed in a gap-healing model. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;87(3):624–631. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miao SD, Lin N, Cheng K, Yang DS, Huang X, Han GR, Weng WJ, Ye ZM. Zn-releasing FHA coating and its enhanced osseointegration ability. J Am Ceram Soc. 2011;94(1):255–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-2916.2010.04038.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagata M, Lonnerdal B. Role of zinc in cellular zinc trafficking and mineralization in a murine osteoblast-like cell line. J Nutr Biochem. 2011;22(2):172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nkenke E, Kloss F, Wiltfang J, Schultze-Mosgau S, Radespiel-Tröger M, Loos K, Neukam FW. Histomorphometric and fluorescence microscopic analysis of bone remodelling after installation of implants using an osteotome technique. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2002;13(6):595–602. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2002.130604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ong JL, Chan DC. Hydroxyapatite and their use as coatings in dental implants: a review. Crit Rev Biomed Eng. 2000;28(5-6):667–707. doi: 10.1615/CritRevBiomedEng.v28.i56.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ong JL, Hoppe CA, Cardenas HL, Cavin R, Carnes DL, Sogal A, Raikar GN. Osteoblast precursor cell activity on HA surfaces of different treatments. J Biomed Mater Res. 1998;39(2):176–183. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199802)39:2<176::AID-JBM2>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palka V, Postrkova E, Koerten HK. Some characteristics of hydroxylapatite powders after plasma spraying. Biomaterials. 1998;19(19):1763–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(98)00087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porter AE, Patel N, Skepper JN, Best SM, Bonfield W. Effect of sintered silicate-substituted hydroxyapatite on remodelling processes at the bone-implant interface. Biomaterials. 2004;25(16):3303–3314. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossi L, Migliaccio S, Corsi A, Marzia M, Bianco P, Teti A, Gambelli L, Cianfarani S, Paoletti F, Branca F. Reduced growth and skeletal changes in zinc-deficient growing rats are due to impaired growth plate activity and inanition. J Nutr. 2001;131(4):1142–1146. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.4.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato M, Alslani A, Sambito MA, Kalkhoran NM, Slamovich EB, Webster TJ. Nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite/titania coatings on titanium improves osteoblast adhesion. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;84(1):265–272. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schenk RK, Buser D. Osseointegration: a reality. Periodontol 2000. 1998;17(1):22–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1998.tb00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suh JY, Jeung OC, Choi BJ, Park JW. Effects of a novel calcium titanate coating on the osseointegration of blasted endosseous implants in rabbit tibias. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2007;18(3):362–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2006.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szmukler-Moncler S, Perrin D, Ahossi V, Magnin G, Bernard JP. Biological properties of acid etched titanium implants: effect of sandblasting on bone anchorage. J Biomed Mater Res Part B: Appl Biomater. 2004;68(2):149–159. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.20003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang F, Dong WJ, He FM, De XX, Zhao SF, Yang GL. Osteoblast response to porous titanium surfaces coated with zinc-substituted hydroxyapatite. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;113(3):313–318. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang GL, He FM, Zhao SS, Zhao SF. Effect of H2O2/HCl heat treatment of implants on in vivo peri-implant bone formation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2008;23(6):1020–1028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang GL, He FM, Hu JA, Wang XX, Zhao SF. Effects of biomimetically and electrochemically deposited nano-hydroxyapatite coatings on osseointegration of porous titanium implants. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107(6):782–789. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang GL, He FM, Yang XF, Wang XX, Zhao SF. In vivo evaluation of bone-bonding ability of RGD-coated porous implant using layer-by-layer electrostatic self-assembly. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;90(1):175–185. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang GL, He FM, Hu JA, Zhao SF. Biomechanical comparison of biomimetically and electrochemically deposited hydroxyapatite coated porous titanium implants. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(2):420–427. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang GL, He FM, Song E, Wang XX, Zhao SF. In vivo evaluation of bone formation on roughened titanium implant surfaces with biomimetic and electrochemically deposited nano-hydroxyapatite. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2010;25(4):669–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]