Abstract

Mutations in the serine palmitoyltransferase subunit 1 (SPTLC1) gene are the most common cause of hereditary sensory neuropathy type 1 (HSN1). Here we report the clinical and molecular consequences of a particular mutation (p.S331Y) in SPTLC1 affecting a patient with severe, diffuse muscle wasting and hypotonia, prominent distal sensory disturbances, joint hypermobility, bilateral cataracts and considerable growth retardation. Normal plasma sphingolipids were unchanged but 1-deoxy-sphingolipids were significantly elevated. In contrast to other HSN patients reported so far, our findings strongly indicate that mutations at amino acid position Ser331 of the SPTLC1 gene lead to a distinct syndrome.

Keywords: HSN, HSAN, SPTLC1, Cataract, Hereditary neuropathy

Highlights

-

•

Novel mutation associated with a distinct new phenotype.

-

•

Most interesting because of possible upcoming therapeutic options.

-

•

Elevated 1-deoxy-sphingolipids levels.

1. Introduction

Hereditary sensory neuropathies (HSN) are clinically and genetically heterogeneous disorders of autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive inheritance characterized by axonal atrophy and degeneration, predominantly affecting the sensory neurons [1–3]. Hallmark features of the dominantly inherited variant subclassified as HSN type 1 (HSN1) comprise severe distal sensory loss, painless injuries, skin ulcers and frequent bone infections that sometimes necessitate amputations of toes or feet [1–3]. Disease onset is usually in early adulthood. Variable distal muscle weakness and wasting and lancinating pain is also often observed. With disease progression the hands may become involved similarly [1–3]. Mutations in the serine-palmitoyltransferase, long chain base subunit 1 (SPTLC1) gene are the most frequent cause of HSN1 [4,5]. SPTLC1 encodes one of the three subunits of serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT), which catalyzes the first step in the de-novo synthesis of sphingolipids which is the condensation of l-serine and palmitoyl-coenzyme A. Under certain conditions SPT shows a shift from its canonical substrate l-serine to the alternative substrates l-alanine and glycine which leads to the formation of an atypical class of 1-deoxy-sphingolipids (1-deoxySL). Low levels of 1-deoxySLs are typically present in plasma of healthy individuals. Pathologically elevated 1-deoxySLs have been found in transgenic HSN1 mouse models and in HSN1 patients carrying different SPTLC1 mutations but also in individuals with the metabolic syndrome and diabetes [6–8]. The 1-deoxySLs show pronounced neurotoxic effects in vitro and may be disease causing in HSN1 but are possibly also involved in the pathology of the diabetic neuropathy. The observation that a high dose l-serine supplementation lowers plasma 1-deoxySL levels in HSN1 patients and in the transgenic mouse model has encouraged our hopes for a first treatment of this ulcero-mutilating disorder. This emphasizes the importance of an early and accurate genetic diagnosis of HSN1 patients [9]. Here we report a novel SPTLC1 mutation in a female patient exhibiting an unusually severe and complicated phenotype. We show that mutations at the particular amino acid position Serine 331 (S331) are associated with a distinct syndromic phenotype in comparison to previously reported mutations in HSN1.

2. Patient and methods

The female proband was the first child of non-consanguineous and healthy parents. Pregnancy was normal but she was born by cesarean delivery three weeks early. Motor milestones during the first years were normal but height and weight always ranked low in percentile or they were even below the lower limit. At 4 years of age a strange gait, frequent falls and moderate hand tremor were noted. Sensory disturbances were initially mild but progressed with disease. Considerable pes cavus foot deformity necessitated triple arthrodesis at age 5. Subsequently, the diagnosis of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy (HMSN) was made. Disease progression was rapid and soon muscle weakness and wasting affected upper limbs, but also proximal limb and trunk muscles thus leading to severe scoliosis, respiratory problems and wheelchair dependence at age 14. In addition, there was prominent growth retardation and delayed puberty whereas intellectual development was normal. At age 13, bilateral cataracts were diagnosed and surgically treated.

On examination at age 12 years there was general muscle hypotrophy and hypotonia with pronounced weakness in the distal muscles of the upper and lower limbs (Fig. 1). There were prominent sensory disturbances which were pronounced in the feet and affected all qualities except for the vibration sense which remained completely preserved. At the toes scars after burns due to reduced prominent pain and temperature sensation were evident (Fig. 1, arrow). Hypermobility of the joints, bilateral hand tremor and fasciculations, which were most prominent in the tongue, were observed (Fig. 1). Tendon reflexes were brisk but the Babinski sign was negative.

Fig. 1.

Clinical features of the patient. Diffuse muscle hypotrophy and hypermobility of joints in the patient carrying the p.S331Y SPTLC1 mutation. Note scars at the toes (arrow) after burns due to reduced pain and temperature sensation.

Further evaluation included nerve conduction studies (NCS), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies and molecular genetic testing which followed standard methods. Whole exome sequencing was performed on a Genome Analyzer HiSeq 2000 system (Illumina, San Diego, CA.). Methods and parameters were used as shown previously [10]. The plasma sphingoid base profile and cellular SPT activity was analyzed as described previously [11]. The study was approved by the local ethical committee.

3. Results

Nerve conduction velocities in the upper limbs were within the intermediate range (median motor: 32 m/s, median sensory: 39 m/s, SNAP: 16.7 μV) and compound motor action potentials (CMAP: 2.5 mV, peak–peak) were reduced. There was no response for motor or sensory nerves in the lower limbs. Based on these results the patient was initially classified as HMSN type II. MRI of the brain and spinal cord was normal at the age of 9 years. Endocrinological examination of the patient did not reveal any additional disturbances.

After exclusion of mutations in all common HMSN and SCA (spino-cerebellar ataxia) genes, whole exome sequencing was carried out. Thereby, a heterozygous missense change in SPTLC1 (c.992G- > T; p.S331Y) was detected and confirmed by Sanger re-sequencing. The parents were normal on neurological and on electrophysiological examination and this change was absent in both of them. Also, no sequence variation at aa position S331 was found in 1969 individuals from our in-house exomes.

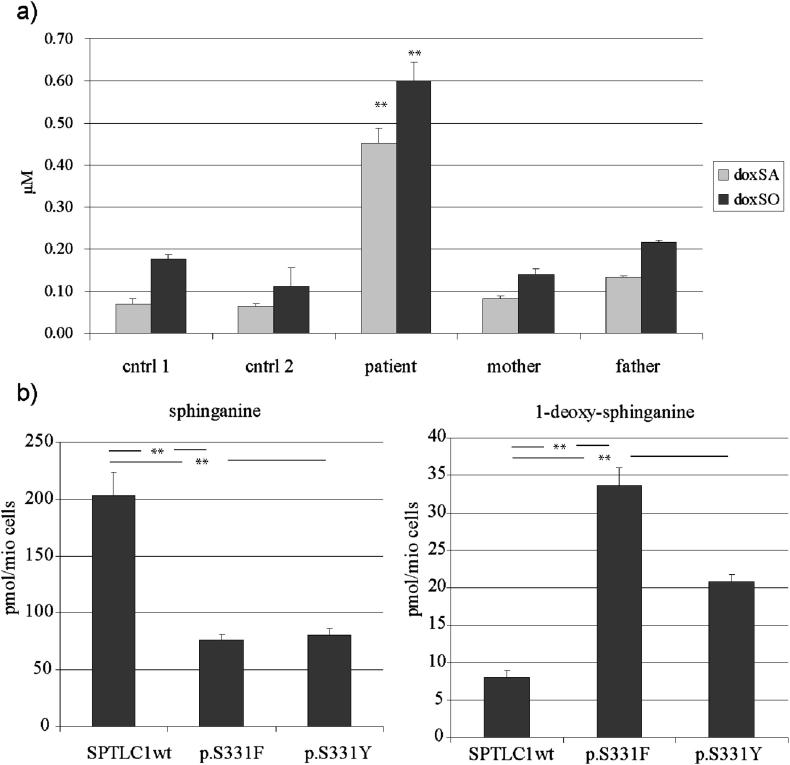

Subsequently, we measured the 1-deoxySL levels in the patients' plasma which were found to be significantly elevated (Fig. 2a). Increased 1-deoxySL formation was also confirmed in HEK293 cells expressing the p.S331F and p.S331Y mutant (Fig. 2b). In comparison 1-deoxySL formation was lower in the p.S331Y than in the previously reported p.S331F mutant. Canonical serine activity was reduced by 60% in both mutants.

Fig. 2.

a) 1-DeoxySL levels in plasma samples of the patient carrying the p.S331Y mutation, family members and controls. The levels of the 1-deoxy-sphiglipids were significantly increased in the plasma of the S331Y patient but not in the plasma of the unaffected parents or unrelated healthy controls. Total sphingolipid levels were not different between patients and controls (data not shown). b) De-novo generation of sphinganine and 1-deoxy-sphinganine. HEK293 cells expressing either the S133F or S331Y mutant show a significantly reduced canonical SPT activity and a significantly increased formation of 1-deoxy-sphinganine in comparison to SPTLC1wt expressing cells. The 1-deoxy-sphinganine formation was about 30% lower for the S331Y than for the S331F mutation (**p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

To date, six disease causing mutations in SPTLC1 (p.C133W, p.C133Y, p.C133R, p.V144D, p.S331F, p.A352V) have been described [5]. SPLTC1 mutations at positions p.C133, p.C144 and p.A352 result in the typical HSN1 phenotype [5,12]. In contrast, the p.S331F mutation, which was reported in two patients only, occurred de-novo and was associated with an extraordinary severe and complicated phenotype. One of these patients was initially diagnosed as early onset HMSN type II due to muscle weakness and hypotrophy in addition to prominent sensory disturbances, bone fractures and osteomyelitis. Notably, this patient also developed juvenile cataract at age of 9 years, complete retinal detachment at 10 and repetitive corneal ulceration and keratitis with poor corneal healing [13]. An even more complex congenital phenotype with severe growth retardation, global amyotrophy, hypotonia, joint hyperlaxity, vocal cord paralysis, bilateral cataract, mild mental retardation, microcephaly and respiratory problems was described in the second patient [5]. The pathogenicity of the p.S331F mutation was confirmed by functional studies: in vitro a reduction of SPT activity was shown and in plasma samples of both patients increased levels of 1-deoxySLs were detected [9]. Nevertheless, it remained uncertain whether these additional features were also related to the p.S331F mutation [12]. The patient reported here carries a novel mutation in SPTLC1 leading to a change of serine to tyrosine at aa position 331 which also results in a similar unusually severe and complicated phenotype.

The core phenotype of the three patients described so far carrying an S331 SPTLC1 mutation resembles early onset HMSN. The additional features highly enlarge the phenotype of HSN1 but are rather unique between the three patients (Table 1) thus proposing the existence of a distinct and severe syndrome associated with this particular mutation. Since oral l-Serine supplementation has been suggested to be a future treatment option, it will be most important to achieve a quick diagnosis by early screening of exon 11 of SPTLC1 in patients exhibiting this distinct phenotype.

Table 1.

Core features of the syndromic phenotype produced by the S331 SPTLC1 mutation.

| Reported clinical features as part of the S331–SPTLC1 syndrome | Huehne et al., 2008 [13] (p.S331F) | Rotthier et al., 2009 [5] (p.S331F) | This study (p.S331Y) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffuse muscle hypotrophy | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Growth retardation | nm | Yes | Yes |

| Motor and sensory neuropathy | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Foot ulcers, amputations and/or burns | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Juvenile cataracts | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Mental retardation | nm | Yes | No |

| Joint hypermobility | nm | Yes | Yes |

| Vocal cord paralysis | nm | Yes | No |

| Tremor | nm | nm | Yes |

| Fasciculations | nm | nm | Yes |

| Other ocular manifestations | Yes | nm | No |

| Respiratory problems | nm | Yes | Yes |

Features present in at least two patients are highlighted in bold (nm: not mentioned).

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the patient and her parents for participation in this study. This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF P23223-B19).

References

- 1.Rotthier A., Baets J., Timmerman V., Janssens K. Mechanisms of disease in heriditary sensory and autonomic neuropathies. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2012;8(2):73–85. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auer-Grumbach M., De Jonghe P., Verhoeven K., Timmerman V., Wagner K., Hartung H.P., Nicholson G.A. Autosomal dominant inherited neuropathies with prominent sensory loss and mutilations. Arch. Neurol. 2003;60(3):329–334. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyck P.J. third ed. WB Saunders Company; 1993. Neuronal Atrophy and Degeneration Predominantly Affecting Peripheral Sensory and Autonomic Neurons; pp. 1065–1093. Peripheral Neuropathy. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dawkins J.L., Hulme D.J., Brahmbhatt S.B., Auer-Grumbach M., Nicholson G.A. Mutations in SPTLC1, encoding serine palmitoyltransferase, long chain subunit-1 cause hereditary sensory neuropathy type I. Nat. Genet. 2001;27(3):309–312. doi: 10.1038/85879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rotthier A., Baets J., De Vriendt E., Jacobs A., Auer-Grumbach M., Lévy N., Bonello-Palot N., Kilic S.S., Weis J., Nascimento A., Swinkels M., Kruyt M.C., Jordanova A., De Jonghe P., Timmerman V. Genes for hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathies: a genotype-phenotype correlation. Brain. 2009;132:2699–2711. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertea M., Rütti M.F., Othman A., Marti-Jaun J., Hersberger M., von Eckardstein A., Hornemann T. Deoxysphingoid bases as plasma markers in diabetes mellitus. Lipids Health Dis. 2010;9:84. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-9-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Othman A., Rütti M.F., Ernst D., Saely C.H., Rein P., Drexel H., Porretta-Serapiglia C., Lauria G., Bianchi R., von Eckardstein A., Hornemann T. Plasma deoxysphingolipids: a novel class of biomarkers for the metabolic syndrome? Diabetologia. 2012;55(2):421–431. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2384-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang-Sattler R., Yu Z., Herder C., Messias A.C., Floegel A., He Y., Heim K., Campillos M., Holzapfel C., Thorand B., Grallert H., Xu T., Bader E., Huth C., Mittelstrass K., Döring A., Meisinger C., Gieger C., Prehn C., Roemisch-Margl W., Carstensen M., Xie L., Yamanaka-Okumura H., Xing G., Ceglarek U., Thiery J., Giani G., Lickert H., Lin X., Li Y., Boeing H., Joost H.G., de Angelis M.H., Rathmann W., Suhre K., Prokisch H., Peters A., Meitinger T., Roden M., Wichmann H.E., Pischon T., Adamski J., Illig T. Novel biomarkers for pre-diabetes identified by metabolomics. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2012;8:615. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garofalo K., Penno A., Schmidt B.P., Lee H.J., Frosch M.P., von Eckardstein A., Brown R.H., Hornemann T., Eichler F.S. Oral L-serine supplementation reduces production of neurotoxic deoxysphingolipids in mice and humans with hereditary sensory autonomic neuropathy type 1. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121(12):4735–4745. doi: 10.1172/JCI57549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beetz C., Pieber T.R., Hertel N., Schabhüttl M., Fischer C., Trajanoski S., Graf E., Keiner S., Kurth I., Wieland T., Varga R.E., Timmerman V., Reilly M.M., Strom T.M., Auer-Grumbach M. Exome sequencing identifies a REEP1 mutation involved in distal hereditary motor neuropathy type V. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;91(1):139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penno A., Reilly M.M., Houlden H., Laurá M., Rentsch K., Niederkofler V., Stoeckli E.T., Nicholson G., Eichler F., Brown R.H., Jr., von Eckardstein A., Hornemann T. Hereditary sensory neuropathy type 1 is caused by the accumulation of two neurotoxic sphingolipids. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285(15):11178–11187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.092973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotthier A., Penno A., Rautenstrauß B., Auer-Grumbach M., Stettner G.M., Asselbergh B., Van Hoof K., Sticht H., Lévy N., Timmerman V., Hornemann T., Janssens K. Characterization of two mutations in the SPTLC1 subunit of serine palmitoyltransferase associated with hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy type I. Hum. Mutat. 2011;32(6):E2211–E2225. doi: 10.1002/humu.21481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huehne K., Zweier C., Raab K., Odent S., Bonnaure-Mallet M., Sixou J.L., Landrieu P., Goizet C., Sarlangue J., Baumann M., Eggermann T., Rauch A., Ruppert S., Stettner G.M., Rautenstrauss B. Novel missense, insertion and deletion mutations in the neurotrophic tyrosine kinase receptor type I gene (NTRK1) associated with congenital insensitivity to pain with anhidrosis. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2008;18(2):159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]