Abstract

The Neurospora crassa photoreceptor Vivid tunes blue-light responses and modulates gating of the circadian clock. Crystal structures of dark-state and light-state Vivid reveal a light, oxygen, or voltage Per-Arnt-Sim domain with an unusual N-terminal cap region and a loop insertion that accommodates the flavin cofactor. Photoinduced formation of a cystein-flavin adduct drives flavin protonation to induce an N-terminal conformational change. A cysteine-to-serine substitution remote from the flavin adenine dinucleotide binding site decouples conformational switching from the flavin photocycle and prevents Vivid from sending signals in Neurospora. Key elements of this activation mechanism are conserved by other photosensors such as White Collar-1, ZEITLUPE, ENVOY, and flavin-binding, kelch repeat, F-BOX 1 (FKF1).

The PAS (Per-Arnt-Sim) protein superfamily transduces signals from diverse biological cues, often by coupling cofactor chemistry to alterations in protein conformation or association (1). The canonical PAS domain protein photoactive yellow protein (PYP) and the light, oxygen, or voltage (LOV) PAS subclass sense blue light in bacteria, plants, and fungi (2, 3). Despite extensive photochemical and structural characterization of such blue-light sensors (2, 4–8), the mechanism by which cofactor excitation leads to biological signal propagation remains an open question.

The filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa employs two blue-light sensors with LOV domains, White Collar-1 (WC-1) and Vivid (VVD) to regulate a variety of light responses (9). WC-1 and nonphotosensitive WC-2 form a complex (WCC) that resets the circadian clock by activating transcription of the clock oscillator protein Frequency (FRQ), as well as many other genes (9, 10). VVD, a small PAS protein devoid of auxiliary domains, tunes Neurospora’s blue-light response by attenuating activation of the WCC. VVD is essential for response to changing levels of light and for adaptation under constant light (11–14). VVD and WC-1 share sequence similarity in a core LOV domain and surrounding regions (15). Swapping the WC-1 core LOV domain with that from VVD maintains some light responses in Neurospora (16). VVD and WC-1 require flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) for activity instead of flavin mononucleotide (FMN), which is used by plant and algal LOV-containing proteins known as phototropins (9, 12, 17, 18).

We report the crystal structure of VVD in its dark- and light-adapted states and show how chemical changes at the active center generate conformational change at the N terminus of the protein. We also characterize a Cys-to-Ser residue substitution outside of the canonical LOV domain that decouples the photocycle from conformational switching. Neurospora harboring this mutation lose adaptive light responses, such as the ability to down-regulate carotenoid biosynthesis.

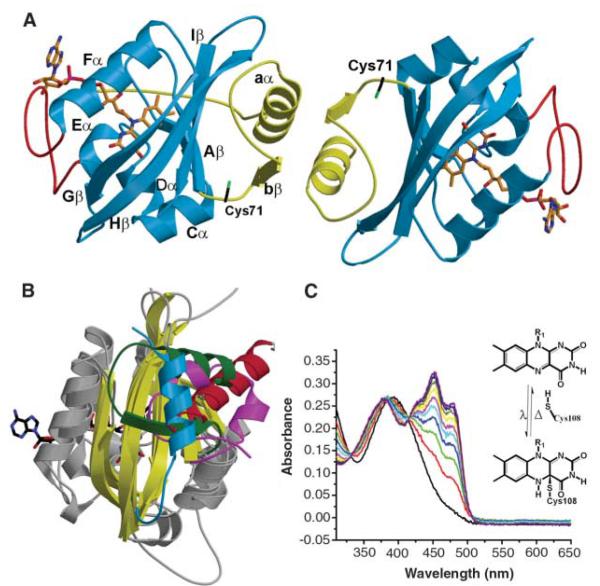

A 36-residue N-terminal truncation of VVD contains the region homologous to the LOV domain of WC-1 and maintains the photochemical properties of the wild type (WT) (Fig. 1) (12); moreover, the shortened protein has dramatically increased solubility and stability at room temperature. The 2.0 Å resolution structure of VVD-36 (table S1) reveals a typical PAS domain topology for the protein core (3) (Fig. 1A and fig. S1). Similar to the phototropins, the flavin isoalloxazine ring binds in a pocket formed by helices Eα and Fα and the three strands of the central β sheet (Aβ, Hβ, and Iβ) (4, 19) (Fig. 1A). Despite these similarities, VVD contains two structural components that distinguish it from phototropin-like LOV domains.

Fig. 1.

VVD structure. (A) Crystallographic dimer of VVD-36, including the PAS core (blue), N-terminal cap (yellow), and FAD insertion loop (red). The N terminus, resolved only in the left molecule, projects toward the solvent-exposed FAD adenosine moiety (orange). (B) Superposition of the PAS domains of VVD (green), PYP (magenta), Drosophila PER (red), and AsLOV2 domain (blue). All proteins share a structurally conserved PAS β scaffold (yellow) and helical regions (gray) that pack with a variable helical element possibly involved in signal transduction. (C) Photocycle of VVD-36 at 25°C. Blue-light illumination of VVD forms a photoadduct between Cys108 and the C4a position of the flavin ring (inset). Adduct formation bleaches the flavin absorption bands at 428, 450, and 478 nm and produces a single peak at 390 nm. Recovery proceeds with t1/2 = 104 s and three isosbestic points at 330, 385, and 413 nm. Spectra are displayed at 3000 s increments.

First, an 11-residue inserted loop between Eα and the helical connector (Fα) accommodates the adenosine moiety of FAD at the surface of the protein (Fig. 1A). The blue-light using FAD (BLUF) family of FAD-containing light sensors also places the adenosine in a solvent-exposed environment, where it has been proposed to mediate protein/protein interactions (20). Nevertheless, in full-length VVD, residues 1 to 36 (absent in VVD-36) may sequester the adenosine moiety in the dark state. Second, an N-terminal cap (residues 37 to 70) that includes helix aα and strand bβ differs in structure from analogous regions of known PAS proteins (Fig. 1, A and B). In two different crystal forms, VVD associates as a symmetric dimer via a hydrophobic face of aα (Fig. 1A). However, in solution, VVD is monomeric for both dark- and light-adapted states. The N-terminal cap in VVD-36 resides at a similar position against the canonical β sheet as the N-terminal cap in PYP (3), the C-terminal Jα-helix in the Avena sativa LOV2 domain (AsLOV2 phototropin) (5), and the αF helix in the Drosophila clock protein Period (21), all of which have been implicated in conformational switching (Fig. 1B). To date, no definitive evidence has linked conformational changes in these regions to in vivo biological function.

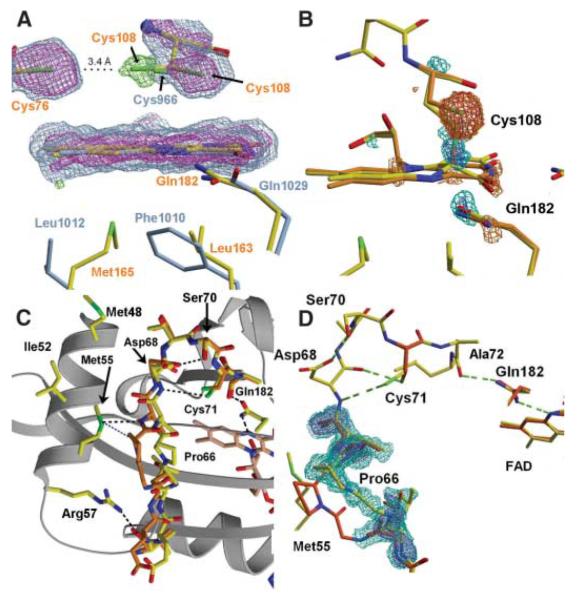

Upon blue-light excitation, VVD undergoes a photocycle similar to that of the LOV domains from phototropins (7, 12). Excitation of the oxidized flavin ring promotes formation of a covalent adduct between a Cys thiol and the flavin C4a position (Fig. 1C). Attack of the thiol at C4a reduces the flavin ring, breaks aromaticity, and bleaches the absorption bands at 450 and 478 nm (Fig. 1C and fig. S2). Scission of the thioether bond and return to the dark state at room temperature is much slower (t1/2 = 1 × 104 s) than seen in phototropins (t1/2 = ~200 s) (22), but similar to the recovery of the LOV-containing protein YTvA (~3 × 103 s) (23) (Fig. 1C). In VVD, conserved Cys108 is directly above the C4a position in the dark-state structure, but the residues surrounding the flavin ring differ considerably from those found in structurally characterized phototropins (Fig. 2A) (2, 12). Similar to that observed in an algal LOV1 domain (4), an alternative, minority conformation is found for the active center Cys. In VVD, this minority conformer places the Cys108 thiol within 3.4 Å of conserved Cys76, which is at the end of a water channel leading to the flavin (Fig. 2A). The two Cys residues are close enough for disulfide bond formation; however, substantial adjustments would be necessary to obtain optimum disulfide geometry. Oxidation or modification at either Cys could inhibit VVD from forming the light-state adduct and provide a means for regulation of VVD activity by reactive oxygen species (24).

Fig. 2.

The VVD light state in crystals. (A) Superposition of VVD (yellow) and Adiantum phy3-LOV2 (1G28, blue-gray) active centers show differences in residue composition beneath the flavin [1.5 σ (aqua) and 3.0 σ (purple), 2Fobs – Fcalc electron density]. An alternate conformation of Cys108 contacts conserved Cys76 [3.0 σ (green), Fobs – Fcalc electron density]. (B) Structural differences in the light state of VVD. Difference electron density reveals covalent bond formation between Cys108 and flavin C4a and flipping of the Gln182 amide in response to N5 protonation. Fobs – Fcalc electron density [2.0 σ (aqua), 3.0 σ (blue), −2.0 σ (orange), and −3.0 σ (red)], with Fcalc calculated from a model refined with 100% of the dark-state conformation. (C) Expanded view of the structural changes propagating from Gln182 to aα and bβ in the VVD-36 light state. Pro66 undergoes the largest shift (2.0 Å) in the light state (yellow) versus the dark state (orange). Hydrogen bonds (dashed lines) are shown for d < 3.2 Å; except for Cys71-to-Asp68 amide, where d = 3.9 Å. Other key contacts are shown in blue. (D) The hinge region between the PAS core and bβ. In the light state, Gln182 rotates to improve interactions between the Gln182 amide and the Ala72 carbonyl, Cys71 swivels to hydrogen-bond with the Asp68 amide nitrogen, and bβ shifts 2 Å. Fobs – Fcalc omit electron density [1.5 σ (aqua) and 3.0 σ (purple)] calculated with bβ absent from the model.

To probe conformational changes in the flavin adduct state of VVD-36, structures were determined for photo-bleached crystals (table S1). A high-occupancy/high resolution (1.7 Å) light-state structure was determined by combining the first 30 frames of diffraction data from four different crystals that were exposed to light before rapid cooling in liquid N2. Exposure to the synchrotron beam reduces the VVD flavin and breaks the C4a adduct; thus, only minimally exposed crystals contain a significant fraction (~50%) of the covalently coupled cofactor. Difference Fourier electron-density maps (Fobserved – Fcalculated) (Fig. 2B and fig. S3) reveal clear bonding of Cys108 to flavin C4a and conformational changes at Gln182, which hydrogen-bonds with flavin N5. Thioether bond formation reduces the flavin ring and protonates N5. To maintain a hydrogen bond with protonated N5, the amide of Gln182 must flip (4, 25, 26). The VVD structure at 1.7 Å resolution shows clear difference density for flipping of the Gln182 amide (Fig. 2B). Moreover, these altered interactions of Gln182 subtly affect the conformation of a hinge region connecting the N-terminal cap to the PAS core. In the dark state, the side-chain carbonyl of Gln182 abuts the carbonyl carbon of Ala72 (Fig. 2, C and D). In the light state, the Gln182 flip replaces this potentially unfavorable contact with a hydrogen bond between the Ala72 carbonyl and the Gln182 amide nitrogen. The Gln182 flip alters dipole orientations and perhaps stabilizes Ala72 against bβ (Fig. 2, C and D). The Cys71 thiol breaks a buried hydrogen bond to the Asp68 carbonyl and rotates into a more exposed position to interact with the Asp68 peptide nitrogen (Fig. 2D and fig. S4). The altered interactions of Cys71 correlate with a shift in bβ of 2.0 Å toward the PAS core (Fig. 2, C and D). The translation of bβ disrupts interactions made by Met55 and Arg57 that otherwise stabilize packing of the N-terminal cap against the PAS β sheet (Fig. 2C). No other major structural changes are observed in the crystalline protein on photoexcitation. For example, there were no perturbations to a salt bridge between Asp82 and Arg109 that has been suggested to mediate conformational changes within the phototropins and YtvA (6, 25, 27).

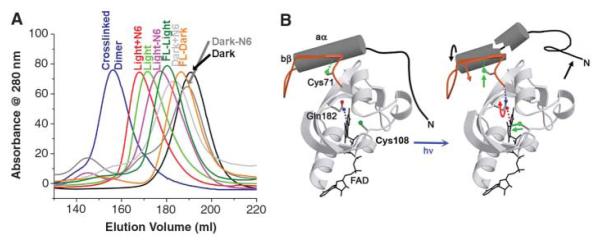

Although structural changes in the bleached crystal are modest, VVD-36 undergoes a large change in hydrodynamic radius on solution excitation that is readily apparent on a sizing column because of slow recovery of the light state (Fig. 3A and table S2). This shift in elution volume is less pronounced in full-length VVD and smaller than the change that would be caused by dimerization (Fig. 3A). Addition of disordered residues to the N terminus increases the apparent size of both the light and dark states, but removal of N-terminal residues structured in the dark state down-shifts the apparent size of only the light state (Fig. 3A). Thus, the larger hydrodynamic volume for the VVD-36 light state results from increased disorder at the N terminus. Small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) measurements confirm that the electron density of VVD-36 is more widely distributed in the light state than in the dark state but that VVD-36 does not undergo dimerization (fig. S5).

Fig. 3.

Increase of the VVD-36 hydrodynamic radius on light excitation. (A) Elution profiles of VVD variants from a size-exclusion column. Light-state VVD (green) elutes at a much larger apparent molecular weight than does dark-state VVD (black), but smaller than a disulfide cross-linked dimer (purple). Addition of a His6 tag to the VVD N terminus shifts the elution profile of both the dark state (light gray) and the light state (red). Truncation of six residues does not affect the dark state (dark gray) but significantly shifts the light state (pink). Full-length VVD undergoes a smaller shift in the light state (dark green) relative to the dark state (orange). (B) Model of the coupled chemical and conformational changes caused by VVD light activation.

The LOV2 phototropin C-terminal Jα helix and PYP N-terminal helices undergo light-induced dissociations from their respective PAS cores (5, 28, 29). In contrast, aα in the VVD light-adapted state is unlikely to completely release from the β sheet because mutations made to destabilize aα against the PAS core (e.g., Leu51Glu and Ile54Glu) result in unstable, poorly expressed proteins. Furthermore, the face of aα that is completely exposed in the dark state may make new contacts with the protein core in the light state because some substitutions here (e.g., Ile52Arg) prevent conformational switching. The importance of Gln182 for coupling conformational change at the N terminus to the flavin is highlighted by the Gln182Leu mutant, which upon light excitation exhibits normal spectral properties but is defective in switching between the compact and fully expanded conformations (Fig. 4A). Our combined data suggests a model where structural changes in VVD-36 propagate to the N-terminal helix aα, which repacks on the protein surface so as to release the N terminus from the protein core (Fig. 3B).

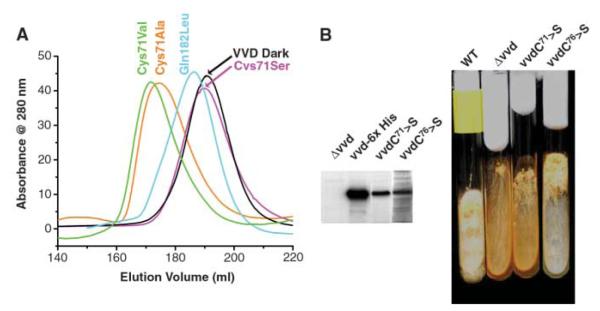

Fig. 4.

Decoupling the VVD photocycle from signal transduction. (A) Light-state elution profile of VVD-36 variants. A C71A mutant (orange) and C71V mutant (green) adopt the expanded state on light excitation, whereas C71S (pink) cannot. Q182L (aqua) elutes at a position slightly larger than VVD-36 dark (black) but does not respond normally to light excitation. (B) VVD C71S is incapable of transmitting blue light signals in Neurospora. (Left) Western blots of cellular extracts with an antibody to VVD. The vvd null mutant contains no VVD protein, whereas the protein is abundant when complemented with WT VVD containing a 6-His tag, C71S, or C76S. (Right) Slant cultures of Neurospora crassa grown under constant light conditions. The vvd null and C71S mutants accumulate large amounts of carotenoids as a result of loss of light adaptation, giving the cells an orange color. In contrast, complementation with C76S yields WT behavior.

Mutagenesis experiments designed to probe conformational changes involving the N-terminal cap reveal that substitution of Cys71 to Ser completely prevents the N-terminal conformational change (Fig. 4A) but has no other effect on the flavin photocycle (t1/2 = 1 × 104 s). Cys71, which is conserved in WC-1 and other FAD-binding LOV domains (fig. S1), switches hydrogen-bonding partners upon conversion to the light state (Fig. 2, C and D, and fig. S4). In the 1.8 Å resolution structure of the Cys71Ser mutant, Ser71 hydrogen-bonds more closely with the Asp68 carbonyl than does Cys71 in the WT. Presumably, this buried hydrogen bond stabilizes the loop structure against movement otherwise induced by the altered conformation of Gln182. Substitutions that remove a polar group for hydrogen bonding (Cys71Ala and Cys71Val) recover expansion on light excitation (Fig. 4A). Cys71Ser decouples formation and breakage of the C4a adduct from conformational changes at the N terminus.

Both small and large amplitude conformational changes have been implicated in signal propagation by PAS domain proteins (2, 21, 28, 30–32); however, it has been challenging to link conformational changes to a biological function in vivo. We performed in vivo complementation studies of VVD Cys71Ser in Neurospora to demonstrate that light-induced conformational changes involving the N-terminal cap are essential for cellular function. Introduction of the Cys71Ser mutant into a vvd null background demonstrates that the ability of VVD to down-regulate carotenoid production under constant light conditions is completely lost in the decoupled mutant (Fig. 4B). In contrast, a Cys mutant close to the active center, which does not perturb the conformational change (Cys76Ser), behaves as the WT protein when reintroduced to cells (Fig. 4B).

No immediate targets of VVD are known, but its signal must be relayed to the principal photoreceptor of the cell, WC-1. WC-1 likely functions analogously to VVD, because it conserves all of the key structural elements necessary for the VVD conformational switch (fig. S1). When bound to DNA, the WCC migrates with a larger hydrodynamic radius in a gel-shift assay on light excitation (18).

Other light sensors, such as WC-1, ENVOY, ZEITLUPE, and FKF-1, have similar residues in elements important for VVD’s switching mechanism (fig. S1). The VVD Cys71 variants demonstrate that some substitutions are tolerated at key positions, such as the equivalent Val found in ENVOY. Interestingly, conformational changes in VVD involve contacts between side chains that are reasonably well conserved (Gln182 and Cys71) to the peptide backbone of more variable positions (Ala72, Asp68, and Pro66). FKF1, a distant relative of VVD, contains a Ser at position 71 but also exhibits a deletion of bβ that may compensate by altering the hinge structure. Compared with the core and hinge regions, the N termini within this family are highly divergent, which provides the means to couple with a variety of output signals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from NIH (MH44651 to J.C.D. and J.J.L., R37GM34985 to J.C.D., and GM079879-01 to B.R.C.) and the Searle Scholars Program (to B.R.C.). Coordinates and Structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (accession number for VVD is 2PD7, for Cys71Ser mutant, 2PD8; for photoexcited VVD, 2PDR; for phosphodiesterase-treated VVD, 2PDT). We thank R. Gillilan for help with SAXS, and the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source and the National Synchrotron Light Source for access to data collection facilities.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/316/5827/1054/DC1 Materials and Methods Figs. S1 to S5 Tables S1 and S2 References

References and Notes

- 1.Taylor B, Zhulin IB. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999;63:479. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.479-506.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crosson S, Rajagopal S, Moffat K. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2. doi: 10.1021/bi026978l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pellequer J-L, Wager-Smith KA, Kay SA, Getzoff ED. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:5884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.5884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fedorov R, et al. Biophys. J. 2003;84:2474. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75052-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harper SM, Neil LC, Gardner KH. Science. 2003;301:1541. doi: 10.1126/science.1086810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Losi A, Ghiraldelli E, Jansen S, Gartner W. Photochem. Photobiol. 2005;81:1145. doi: 10.1562/2005-05-25-RA-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salomon M, Christie JM, Knieb E, Lempert U, Briggs WR. Biochemistry. 2000;39:9401. doi: 10.1021/bi000585+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swartz TE, Wenzel PJ, Corchnoy SB, Briggs WR, Bogomolni RA. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7183. doi: 10.1021/bi025861u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loros JJ, Dunlap JC. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2001;63:757. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee K, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC. Science. 2000;289:107. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5476.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heintzen C, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC. Cell. 2001;104:453. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwerdtfeger C, Linden H. EMBO J. 2003;22:4846. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shrode LB, Lewis ZA, White LD, Bell-Pedersen D, Ebbole DJ. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2001;32:169. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.2001.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elvin M, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC, Heintzen C. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2593. doi: 10.1101/gad.349305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ballario P, Giuseppe M. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:458. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01144-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng P, He Q, Yang Y, Wang L, Liu Y. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:5938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031791100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He Q, et al. Science. 2002;297:840. doi: 10.1126/science.1072795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Froehlich A, Liu Y, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC. Science. 2002;297:815. doi: 10.1126/science.1073681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crosson S, Moffat K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:2995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051520298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jung A, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:12350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500722102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yildiz Ö, et al. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:69. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kottke T, Heberle J, Hehn D, Dick B, Hegemann P. Biophys. J. 2003;84:1192. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74933-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Losi A, Quest B, Gartner W. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2003;2:759. doi: 10.1039/b301782f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshida Y, Hasunuma K. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:6986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310060200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crosson S, Moffat K. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1067. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nozaki D, et al. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8373. doi: 10.1021/bi0494727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crosson S, Rajagopal S, Moffat K. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2. doi: 10.1021/bi026978l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harper SM, Christie JM, Gardner KH. Biochemistry. 2004;43:16184. doi: 10.1021/bi048092i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bernard C, et al. Structure. 2005;13:953. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Losi A, Kottke T, Hegemann P. Biophys. J. 2004;86:1051. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74180-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rubinstenn G, et al. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998;5:568. doi: 10.1038/823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brudler R, et al. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;363:148. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.