Background: The fibronectin (FN)-collagen interaction is important for cell adhesion and migration.

Results: FN modules 8–9FnI interact with two distinct sites in both chains of collagen I. All six collagen-binding FN modules interact cooperatively with a single collagen site.

Conclusion: Collagen I possesses four equipotent sites for FN.

Significance: We have mapped FN binding to collagen I and demonstrated the first cooperative interaction.

Keywords: Collagen, Extracellular Matrix Proteins, Fibronectin, NMR, X-ray Crystallography, GBD, SAXS

Abstract

Despite its biological importance, the interaction between fibronectin (FN) and collagen, two abundant and crucial tissue components, has not been well characterized on a structural level. Here, we analyzed the four interactions formed between epitopes of collagen type I and the collagen-binding fragment (gelatin-binding domain (GBD)) of human FN using solution NMR, fluorescence, and small angle x-ray scattering methods. Collagen association with FN modules 8–9FnI occurs through a conserved structural mechanism but exhibits a 400-fold disparity in affinity between collagen sites. This disparity is reduced in the full-length GBD, as 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI binds a specific collagen epitope next to the weakest 8–9FnI-binding site. The cooperative engagement of all GBD modules with collagen results in four broadly equipotent FN-collagen interaction sites. Collagen association stabilizes a distinct monomeric GBD conformation in solution, giving further evidence to the view that FN fragments form well defined functional and structural units.

Introduction

Fibronectin (FN)3 and collagen, two essential components of the extracellular matrix, are key players in diverse cellular processes, including adhesion, migration, growth, and differentiation (1, 2). FN is a high molecular weight multidomain protein composed of three conserved module types (I, II, and III), individual structures of which have been elucidated previously (3). Biophysical studies initially suggested that FN modules are arranged sequentially, similar to beads on a string (4–6). However, more recent studies have shown the presence of compact multidomain units in FN (7–10), including the six FN modules that are important for binding to collagen (6FnI1–2FnII7–9FnI) (7, 8, 11–13).

The FN-collagen interaction is well documented (14), but its molecular details have remained elusive until recently. It has long been known that FN is crucial for fibroblast attachment to collagen matrices (15, 16) and for organization of collagen type I fibrils (17). In vitro, however, 6FnI1–2FnII7–9FnI binds strongly to gelatin, the denatured form of collagen (18, 19), but not to triple-helical collagen fibrils; 6FnI1–2FnII7–9FnI was thus named the “gelatin-binding domain” (GBD). To reconcile the in vitro and cellular findings, it was suggested that the physiological function of the FN-collagen interaction is related to clearance of denatured collagenous material during wound repair (20, 21) and binding of exposed single collagen chains (15) following fiber processing by matrix metalloproteinases during tissue growth (22). However, recent work suggested that the collagen triple helix unfolds locally at physiological temperatures (23–25), which suggested the possibility that FN could also interact with unwound collagen in intact fibers.

Previous work from our laboratory revealed that FN binds tightly to a consensus sequence on D-period 4 of the collagen type I α1 and α2 chains (26), just C-terminal of the MMP-1 cleavage site (27). The crystallographic structure of the complex between an α1 peptide from this site and 8–9FnI revealed that the collagen peptide extends the 8FnI antiparallel β-sheet by one strand (26), reminiscent of proteins from pathogenic bacteria bound to FnI modules (28, 29). Furthermore, we demonstrated that 8–9FnI can unwind triple-helical peptides from the same site in a concentration dependent manner (26).

What is the role of the remaining GBD modules? We recently proposed a composite GBD model from the isolated crystallographic structures of 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI and 8–9FnI (7) and suggested that a suitably long collagen peptide could bind cooperatively to these two GBD subfragments, thereby offering better affinity compared with isolated 8–9FnI binding (26). This model was markedly different from a crystal structure of the GBD in the presence of millimolar concentrations of Zn2+, which showed a dimeric conformation that impaired collagen binding (30). Here, we show that four collagen type I sites bind the GBD with broadly similar affinities, although only one displays a cooperative interaction involving all GBD modules. Ensemble analysis of small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) data showed that the GBD adopts a monomeric conformation in solution, which is further stabilized by collagen peptide binding. Our findings demonstrate how FN fragments form unique functionally competent multidomain units, allowing FN to act as a versatile protein interaction hub in the extracellular matrix (31).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Material Production and Purification

FN fragments corresponding to residues 305–608 (GBD), 305–515 (6FnI1–2FnII7FnI), and 516–608 (8–9FnI) and bearing single amino acid substitutions to improve solubility and protein yields (H307D, N528Q, and R534K) were produced as described previously (7, 26, 32). Synthetic collagen peptides were purchased from GL Biochem (Shanghai, China); their sequences are provided in Table 1, and unless fluorescently tagged, they included a C-terminal tyrosine residue for UV determination of peptide concentration. Fluorescent peptides had 5-carboxyfluorescein attached to the N-terminal amine group.

TABLE 1.

KD values for collagen I peptide binding to FN fragments

α1 and α2 chain numbering is taken to begin at the estimated start of the helical region. “O” in peptide sequences denotes 4-hydroxyproline. NMR, 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum correlation NMR titrations; FA, fluorescence polarization titrations using N-terminal 5-carboxyfluorescein labeling. In titrations where no binding was detected, we typically exceeded 2 mm in peptide concentration.

|

KD |

Method | Name | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GBD | 8–9FnI | 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI | |||

| Collagen type I α1 peptide | |||||

| G70PQGARGLOGTAGLOGMKGHRGFSGLDGAKGDAGPAGPKGEOGSOGENG118 | 98 ± 8 μm | FA | A | ||

| G76LOGTAGLOGMKGHRGFSGLDG97-Y | 143 ± 17 μm | NMR | AN | ||

| G91FSGLDGAKGDAGPAGPKGEOGSOGEN117-Ya | No binding | NMR | AC | ||

| G772PQGIAGQRGVVGLOGQRGERGFOGLOGPSGEOGKQGPSGASGERGPOG820 | 15 ± 2 μm | FA | B | ||

| G775LOGQRGVVGLOGQRGERGFOGLOG799-Y | 5 ± 1 μmb | NMR | BN | ||

| G778QRGSVGLOGQRGERGFOGLOG799-Y | Slow NMR time scale interaction | NMR | |||

| G778QRGVSGLOGQRGERGFOGLOG799-Y | 97 ± 11 μm | NMR | |||

| G796LOGPSGEOGKQGPSGASGER816-Y | No bindingb | NMR | BC | ||

| Collagen type I α2 peptide | |||||

| Q72GARGFOGTOGLOGFKGIRGHNGLDGLKGQOGAOGVKGEOGAOGENG118 | 26 ± 3 μm | FA | C | ||

| G76FOGTOGLOGFKGIRGHNGLDG97-Y | 2.0 ± 0.2 mm | NMR | CN | ||

| G91HNGLDGLKGQOGAOGVKGEOGAOGENG118-Ya | 248 ± 12 μm | NMR | CC | ||

| G772PQGLLGAOGILGLOGSRGERGLOGVAGAVGEPGPLGIAGPOGARGPOG820 | 6 ± 1.0 μm | FA | D | ||

| G778AOGILGLOGSRGERGLOGVAG799-Y | 8 ± 2 μmb | NMR | DN | ||

| G793LOGVAGAVGEOGPLGIAGPOGARGPOG820-Y | No bindingb | NMR | DC | ||

a D. Bihan and R. W. Farndale, unpublished data.

b Published in Ref. 26.

NMR Spectroscopy

NMR spectrometers used superconducting magnets (Oxford Instruments) at 950- and 500-MHz proton resonance frequencies (home-built or Bruker AVANCE II consoles and room temperature or cryogenic probe heads, respectively). Spectra were recorded in PBS (20 mm Na2HPO4 (pH 7.2) and 150 mm NaCl) with 1% 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid as a calibration standard. Experiment temperatures were optimized to avoid resonance broadening due to intermediate exchange phenomena and corresponded to 25 °C (8–9FnI) or 37 °C (6FnI1–2FnII7FnI). Sequential chemical shift assignments were performed earlier (7, 26). Analysis of spectral perturbations upon protein interactions and determination of equilibrium parameters were performed as described (33).

Fluorescence Polarization Experiments

Fluorescence polarization measurements were performed at 25 °C in PBS using SpectraMax M5 (Molecular Devices) and PHERAstar FS (BMG Labtech) fluorometers. Samples of 75 nm labeled peptide and increasing concentrations of protein in 96-well plates were excited at 485 nm with a 515-nm cutoff, and fluorescence was observed at 538 nm. Differences in fluorescence polarization were fit using a single binding model in the program Origin (OriginLab) (33).

X-ray Crystallography

Crystals of the 8–9FnI-AN collagen peptide complex were formed using the vapor diffusion method from sitting drops dispensed by a mosquito® Crystal robot (TPP Labtech). The drops consisted of 100 nl of an equimolar mixture of protein (15 mg/ml) and peptide AN in 10 mm HEPES and 50 mm NaCl (pH 7.0) and 100 nl of reservoir solution containing 4.3 m NaCl and 0.1 m HEPES (pH 7.5). Crystals formed after 3 weeks at 20 °C. They were cryoprotected by transfer to reservoir solution supplemented with 25% (v/v) glycerol and flash-cooled. Data were collected at a resolution of 2.6 Å at beamline ID29 of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF, Grenoble, France). Data were integrated with MOSFLM (34) and scaled with Scala (35). The structure was solved by molecular replacement using Phaser (36) and one 8–9FnI copy (Protein Data Bank code 3EJH) as a search model. Refinement was performed in PHENIX (37) using non-crystallographic symmetry restraints between parts of chains A and B (8–9FnI) and chains E and F (collagen peptide) of the complex and TLS refinement with one group per FnI domain or polypeptide chain. Manual model building was performed in Coot (38). Water positions were manually identified from the electron density map in Coot. Interactions between 8–9FnI and the collagen peptide were analyzed using PDBePISA service from the European Bioinformatics Institute (39).

SAXS Data Collection and Analysis

SAXS data were collected at BioSAXS beamline X33 of the Doris storage ring at the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY, Hamburg, Germany) at 20 °C and 0.15-nm wavelength. Samples in PBS were checked for monodispersity using dynamic light scattering prior to data collection. The GBD was measured at 3, 2, and 1 mg/ml concentrations. The complex of the GBD with collagen peptide C was measured at a 1:1 molar ratio using 42 μm (1.5 mg/ml) GBD. The collagen peptide C concentration was verified using an on-site refractometer. All samples were supplemented with 1 mm dithiothreitol just prior to data collection to avoid radiation damage. A fresh sample of BSA was measured as a standard. Buffer subtraction, intensity normalization, and data merging for the different sample concentrations were performed using PRIMUS (40). The radii of gyration (Rg) were calculated with the AutoRg subroutine in PRIMUS, whereas Dmax values were calculated using autoGNOM (41). Determination of molecular model ensembles that best fit the SAXS data was performed using the ensemble optimization method (42). Quaternary structure modeling was done with SASREF (43) using the crystal structures of 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI (Protein Data Bank code 3MQL) (7) and one copy of 8–9FnI (code 3EJH) (26). Back-calculation of scattering curves from known crystal structures was performed using CRYSOL (44).

Miscellaneous

Collagen type I α1 and α2 numbering is taken to begin at the estimated start of the triple-helical region. This is equivalent to numbering in the UniProt database minus 178 residues for α1 and 90 residues for α2. “O” in peptide sequences denotes 4-hydroxyproline. FN residues correspond to UniProt entry B7ZLF0. The 8–9FnI-BN crystallographic model and data have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (code 3GXE).

RESULTS

The GBD Is an Elongated Monomer in Solution

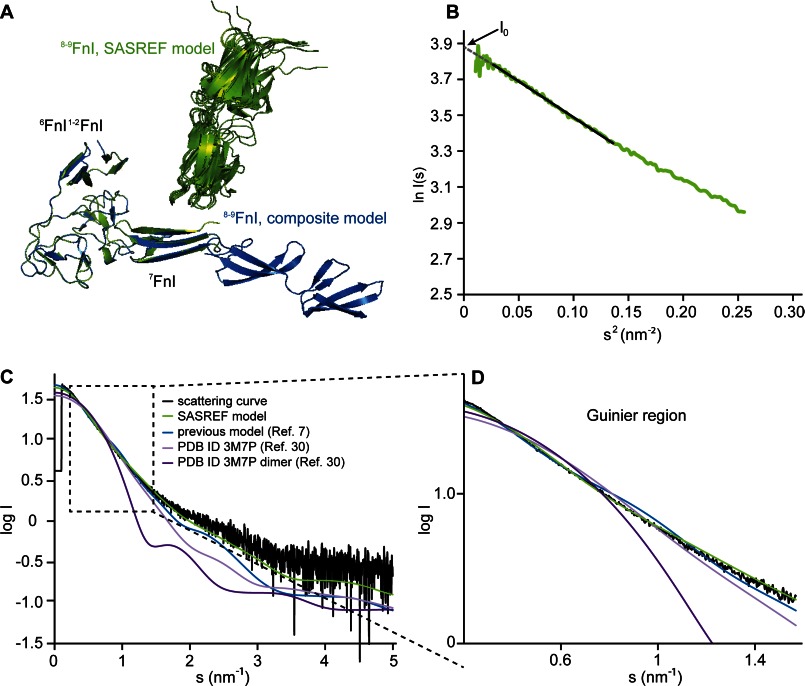

Previously, NMR solution data indicated that FN modules do not undergo radical structural rearrangement in the complete GBD compared with its subfragments 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI and 8–9FnI (7, 26). We therefore proposed a GBD model composed of the two subfragment crystal structures, with an elongated linear arrangement of 7–9FnI protruding from the globular 6FnI1–2FnII (Fig. 1A) (7). To test this model, we performed solution SAXS measurements. Three different concentrations of GBD at 3, 2, and 1 mg/ml yielded consistent scattering curves without any signs of aggregation (data not shown). Because of the higher signal/noise ratio, all further analysis was carried out with the data from the most concentrated sample using the ATSAS software package (45). Guinier analysis suggested a Rg of 3.45 nm and a zero angle intensity (I0) of 48.77 (Fig. 1B). Using BSA as a standard, we calculated a particle molecular mass of 43 kDa, which is within the method error range for a monomeric 35.2-kDa GBD.

FIGURE 1.

SAXS data and GBD structure. A, the previously suggested model of a monomeric GBD (blue) based on the crystal structures of 8–9FnI and 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI (7) compared with 10 SASREF-derived GBD models (green). SAXS analysis suggested an ∼90° kink between 7FnI and 8FnI. B, Guinier analysis of the SAXS curve for the GBD yielded an Rg of 3.45 nm and an I0 of 48.77. C, scattering curve of 3 mg/ml GBD overlaid with back-calculated CRYSOL curves from the previously proposed composite GBD model (blue) (7), monomeric and dimeric versions of the GBD crystal structure (dark and light purple) (30), or the GBD SASREF model (green). D, As expected, the SASREF model fits the measured data best, especially in the crucial low angle region.

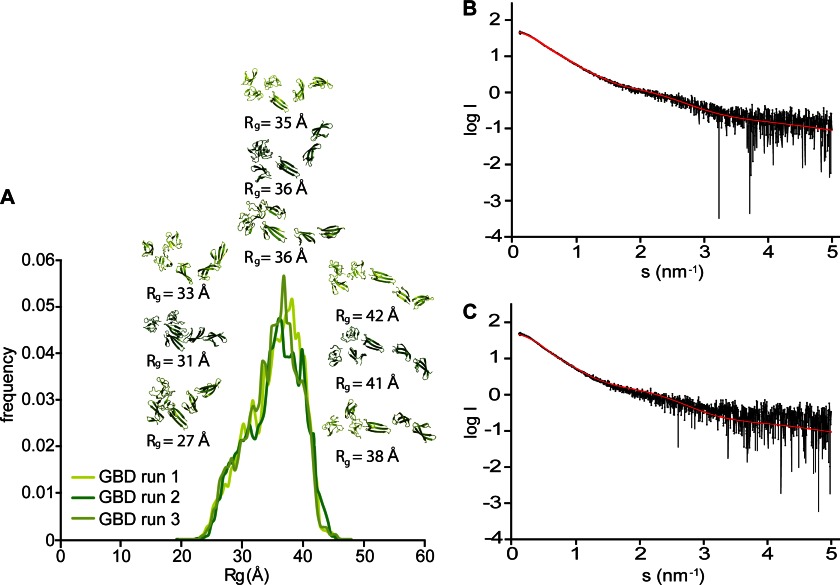

We then used CRYSOL (44) to back-calculate the scattering curve from the composite GBD model, as well as monomeric and dimeric variants of the published GBD crystal structure (30) (Fig. 1, C and D). Comparison of the predicted scattering with the experimental data strongly favors the composite model, especially in the low angle part of the curve (χ = 2.2 versus χ = 6.7 for the crystallographic dimer and χ = 4.2 for the equivalent monomer). However, even our previous composite model does not adequately describe the GBD solution state as judged from the divergence of predicted and experimental scattering at high angles. Ensemble optimization analysis (42) of the scattering data yielded a broad distribution of GBD conformations with a major population cluster at Rg of 3.5–3.6 nm for three independent runs, thereby confirming that this FN fragment has a unique albeit somewhat dynamic conformation in solution (Fig. 2, A and B). We used SASREF (43) to model this GBD conformation starting from either the crystallographic structures of 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI and 8–9FnI or those of 6FnI1–2FnII, 7FnI, and 8–9FnI separately. Independent runs from both inputs yielded a highly similar kinked model with an ∼90° angle between 7FnI and 8FnI (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, 7FnI is stably connected to the 6FnI1–2FnII core, as shown previously in the context of the 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI crystal structure (7). As expected, the back-calculated curve of this kinked model now fits the solution scattering curve much better (χ = 1.45) compared with the initial elongated model (χ = 2.2) (Fig. 1, C and D).

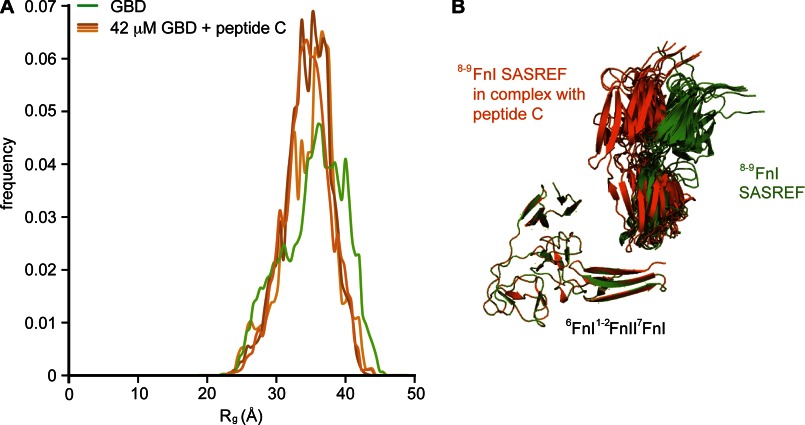

FIGURE 2.

Ensemble optimization analysis of the GBD. A, three independent ensemble optimization method runs of the GBD SAXS data yielded essentially the same distribution, with an average Rg centered at ∼36 Å. At 2 S.D., the width of the Rg distribution of the GBD alone is 17 Å. Sample GBD models corresponding to the center and tail ends of the distribution for all three runs are shown. B and C, representative back-calculated scattering curves for the best ensembles of the GBD alone (B) and in a 1:1 molar complex with peptide C (C) compared with the respective experimental data. χ values are 0.802 (B) and 0.956 (C). χ values below 1 indicate an acceptable fit to the data.

In summary, SAXS data are consistent with a GBD that is a monomeric in solution, with 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI forming a globular particle and a 90° kink between 7FnI and 8FnI. Motions around this kink likely account for the somewhat broad distribution of particle sizes in solution.

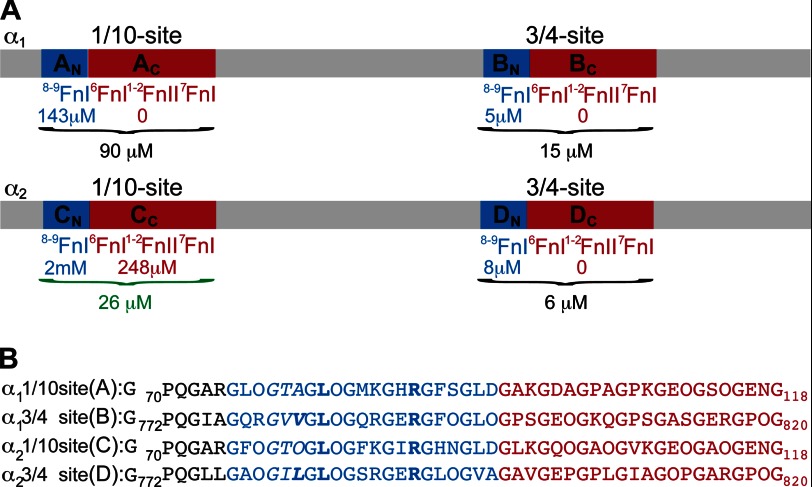

8–9FnI Interacts with Four Sites on Collagen Type I via a Conserved Binding Mode

To firmly establish the elusive molecular interplay between the GBD and the most common collagen (type I), we first need to understand the exact nature of the binding site. On the basis of the 8–9FnI crystal structure in complex with a collagen type I α1 Gly778–Gly799 peptide (BN; see Fig. 3A for a schematic representation of all collagen peptides used here) (26), we previously suggested two potential FN-binding sites on each of the type I α1 and α2 chains. At a distance of ∼1/10 (D-period 1, peptides AN and CN) or 3/4 (D-period 4, peptides BN and DN) from the N terminus of the triple helix, both chains contain a consensus 9-mer 8–9FnI-binding sequence, in which positions 2 and 9 are occupied by leucine and arginine, respectively (Fig. 3B). NMR titrations showed previously (26) that the two 3/4 sites bind to 8–9FnI with high affinity (KD = 5 and 8 μm for BN and DN, respectively).

FIGURE 3.

GBD-binding sites on collagen type I. A, schematic representation of the collagen type I α1 and α2 chains and the two FN-binding sites at 1/10 and 3/4 sequence distance from the collagen N terminus. 8–9FnI-binding sites (peptides AN, BN, CN, and DN) are shown in blue, with the sequences immediately C-terminal thereof (peptides AC, BC, CC, and DC) shown in red. Dissociation constants are indicated. Highlighted in green is the only site where the two GBD subfragments, 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI and 8–9FnI, bind collagen type I cooperatively. B, amino acid sequences of peptides A–D. Conserved positions 2 (Leu) and 9 (Arg) of the 8–9FnI collagen-binding epitope are in shown in boldface; color coding is as in A. The hydrophobic residue-containing triplet that enhances 8–9FnI affinity in the 3/4 sites is indicated in italics, with the crucial hydrophobic residue shown in boldface italics.

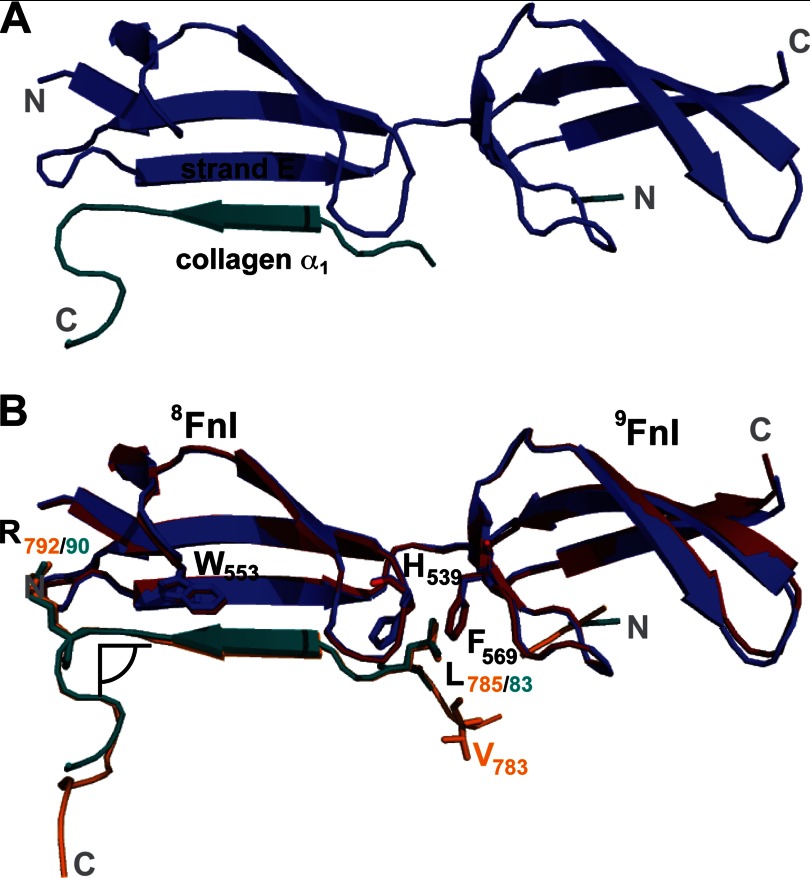

To examine the binding of a collagen 1/10 site, we determined the crystal structure of 8–9FnI in complex with peptide AN. The structure, solved to a resolution of 2.6 Å, showed AN binding in an antiparallel manner to strand E of 8FnI (Fig. 4A; see Table 2 for crystallographic statistics). Thus, the molecular basis of this association is the strand extension mechanism commonly used by complexes involving FnI modules (28, 29), including the high affinity 8–9FnI-BN complex (26). In-depth comparison of 8–9FnI-AN with 8–9FnI-BN revealed a striking similarity in atomic interactions. In both complexes, the indole ring of 8FnI Trp553 stacks above a glycine residue of the peptide main chain (Gly88 in AN), and an important collagen leucine (Leu83) is sandwiched between FN His539 and Phe569 (Fig. 4B). A crucial electrostatic interaction between an arginine (Arg90) on AN and 8FnI Asp516 is also present in both structures. We were therefore surprised by NMR titrations, which revealed significantly weaker 8–9FnI binding affinities for the 1/10 sites (KD = 143 μm for AN and 2 mm for CN) (Fig. 5 and Table 1) compared with their 3/4 counterparts. Comparisons of proton and nitrogen chemical shift changes in 8–9FnI upon addition of collagen peptides showed good correlations between the binding of high (BN and DN) and low (AN and CN) affinity sites (Fig. 6). These chemical shift changes report on structural perturbations induced by complex formation; thus, we conclude that the core binding mechanism of all four collagen sites for 8–9FnI is similar, and the reasons for the apparent differences in affinity must lie elsewhere.

FIGURE 4.

Crystal structure of 8–9FnI in complex with a peptide from the collagen α1 1/10 site. A, schematic representation of the crystal structure of 8–9FnI (blue) in complex with the low affinity peptide AN (cyan). B, overlay of the crystal structure of 8–9FnI (red) in complex with the high affinity peptide BN (orange) (26). The antiparallel β-strand mode of binding alongside strand E of 8FnI is conserved, and the primary hydrophobic contacts are indicated. Val783, which plays an important role in increasing the affinity of peptide BN for 8–9FnI but is not part of the consensus 9-mer sequence, is shown. A peptide hairpin just C-terminal of the consensus binding site in both collagen peptides leads to a 90° kink as indicated.

TABLE 2.

Crystallographic data and refinement statistics

r.m.s.d., root mean square deviation.

| Data statistics | |

| Cell parameters | a = b = 56.57, c = 152.66 Å; α = β = 90°, γ = 120° |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9792 |

| Resolution (Å) | 46.68–2.6 (2.6–2.74) |

| Unique reflections | 16,850 |

| Rmerge | 0.074 (0.442) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 (100.0) |

| Multiplicity | 3.4 (3.5) |

| I/σ(I) | 14.5 (2.4) |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Resolution (Å) | 46.6–2.6 |

| Unique reflections | |

| Working set (%) | 92.6 |

| Free set (%) | 7.4 |

| Rwork | 0.219 |

| Rfree | 0.271 |

| Overall mean B values (Å2) | 57.6 |

| No. of amino acid residues/asymmetric unit (protein and ligand) | 232 |

| No. of water molecules | 44 |

| Matthews coefficient | 2.68 (solvent content, 54.05%) |

| r.m.s.d. from ideal values | |

| Bonds (Å) | 0.003 |

| Angles | 0.683° |

| Estimated overall coordinate error based on maximum likelihood (Å) | 0.990 |

| Ramachandran plot statistics (%) | |

| Residues in favored regions | 95.9 |

| Residues in allowed regions | 4.1 |

| Residues in disallowed regions | 0.0 |

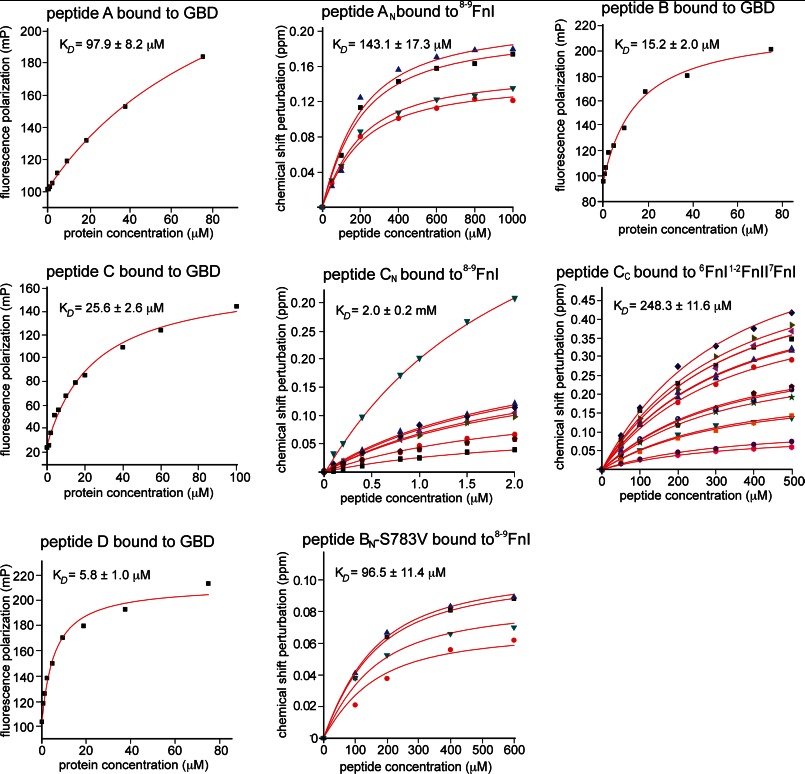

FIGURE 5.

Biophysical studies of collagen interactions with FN modules. Shown here are the protein titration data for interactions summarized in Table 1. For NMR measurements, chemical shift perturbations are plotted against collagen peptide concentration. For fluorescence measurements, we report the polarization of peptide-bound fluorescein against the GBD concentration. All data were fit assuming a single binding event. mP, millipolarization units.

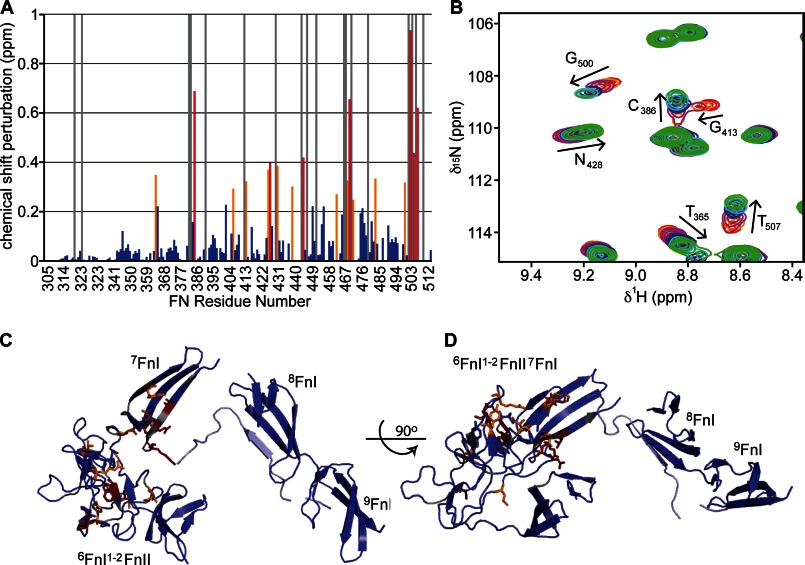

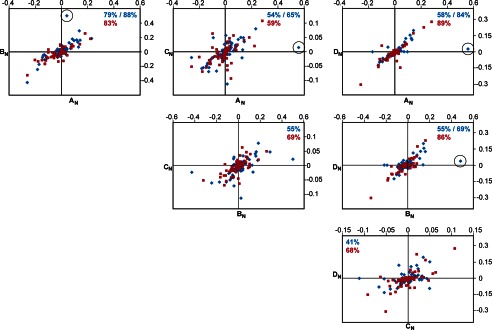

FIGURE 6.

8–9FnI binds collagen through a conserved interaction mode. Shown here are pairwise comparisons of proton (blue) and nitrogen (red) chemical shift changes in 8–9FnI resonances upon addition of collagen peptides AN, BN, CN, and DN. Nitrogen values were divided by a factor of 5 to allow comparison with proton values on the same graph. All values are in ppm. The correlation coefficients (R) of independent linear fits to each data series are indicated in blue (for proton) or red (for nitrogen). In some cases, the coefficients after removal of a single proton data point (circled) are also shown. Note that shift changes for peptides CN and DN are small due to weak binding; thus, experimental errors adversely affect the correlations.

Just N-terminal of the consensus 9-mer sequence, both high affinity collagen 3/4 sites contain two hydrophobic residues, whereas the weaker 1/10 sites harbor a GTA (AN) or GTO (CN) triplet (Fig. 3B). This residue triplet makes no contacts with 8–9FnI in the AN or BN complex structure and has poor local electron density (Fig. 4B). Nonetheless, we reasoned that it could interact transiently with exposed hydrophobic residues of 9FnI, such as Phe569 or Ile592, thereby strengthening the association. To explore this hypothesis, we substituted either Val782 or Val783 in BN with serine and tested for 8–9FnI binding using NMR titrations. Whereas substitution of Val782 did not alter the association significantly, maintaining a slow time scale interaction regime similar to the wild type, when Val783 was changed, the affinity for 8–9FnI dropped to ∼100 μm and a fast interaction regime. Thus, we conclude that although the 8–9FnI binding mode is conserved for all four collagen type I sites, residues outside the central consensus 9-mer sequence influence the association strength. This most adversely affects CN at the 1/10 site of the α2 chain, likely due to the substitution of both hydrophobic residues in the triplet above with highly hydrophilic ones.

The GBD Binds Cooperatively to the Collagen α2 1/10 Site

Could the remaining modules of the GBD strengthen the FN interaction with collagen? Interestingly, the collagen peptide in both 8–9FnI-AN/BN crystal structures displays a 90° kink just C-terminal to the consensus 8–9FnI-binding sequence, stabilized by hydrophobic interactions involving the Phe92 (AN) or Phe794 (BN) side chain and the peptide main chain (Fig. 4B). Hydrophobic residues exist in equivalent positions in CN and DN as well, thus raising the possibility that this peptide kink is a common feature of all four collagen sites (Fig. 3B). This change in peptide direction matches well the relative orientation of 8–9FnI with respect to 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI in the SAXS-derived GBD model presented above. Indeed, when we overlay the 8–9FnI-AN/BN crystal structures onto the SASREF GBD model, the collagen peptides follow the GBD kink, so their C termini would be ideally located to bind to 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI. These findings are consistent with our earlier suggestions of possible cooperative collagen binding to the GBD (7); thus, we explored whether extending the four collagen peptides toward their C terminus increases their affinity for the GBD compared with 8–9FnI.

The long peptides A, B, and D (Fig. 3A and Table 1) bound to the full-length GBD with affinities comparable to 8–9FnI alone, as shown by fluorescence polarization experiments (Fig. 5). These results suggest that 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI does not add significantly to the collagen interaction once 8–9FnI is bound to peptides AN, BN, and DN. This observation was supported by NMR titrations of just the C-terminal segments of these peptides (AC, BC, and DC) (Fig. 3A) with 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI, where no appreciable binding was detected (Table 1). In contrast, the long peptide C, which extends from the weakest 8–9FnI interaction site at the 1/10 position of the α2 chain, interacted with the full-length GBD with KD ≈ 26 μm (Fig. 5), which represents an ∼80-fold enhancement compared with the 8–9FnI-CN interaction alone (Table 1). The C terminus of this peptide (CC) bound 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI with an affinity of KD ∼ 250 μm, as measured by chemical shift analysis of NMR titrations (Figs. 5 and 7, A and B, and Table 1). As shown in Fig. 7 (C and D), structural perturbations upon peptide CC binding to 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI occur over a single molecular surface that extends from the 8–9FnI collagen-binding interface. We conclude that peptide C, the collagen 1/10 site of the α2 chain, binds the full-length GBD and not just the 8–9FnI modules; to our knowledge, this is the first time a specific cooperative binding site for the full-length GBD has been found.

FIGURE 7.

NMR chemical shift analysis of the interaction between 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI and peptide CC. A, combined amide chemical shift differences. Red bars indicate perturbations >2 S.D. from the mean, and orange bars indicate perturbations >1 S.D. Blue bars denote measured chemical shift perturbations < 1 S.D. Gray bars indicate peak disappearance upon titration with the peptide. B, region of a 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum correlation NMR spectrum showing an overlay of 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI resonances that shift upon addition of peptide CC. C and D, two perpendicular representations of the GBD SASREF model with residues in stick representations and colored according to the chemical shift perturbations found in A. The light blue collagen peptide indicates how the most perturbed residues in 2FnII and 7FnI can form a continuous collagen-binding interface with 8–9FnI.

Collagen Binding Stabilizes the Solution GBD Conformation

To investigate the effects of the cooperative binding of collagen peptide C to the GBD structure, we measured SAXS data on this 1:1 complex and obtained scattering curves without any sign of aggregation. Three independent ensemble analysis runs of these data yielded a monodisperse distribution of molecular models, with an average Rg of ∼3.5 nm (Figs. 2C and 8A), which is essentially identical to the major population cluster of the GBD alone. Although the fit is still reasonable, it deviates further than calculations of the GBD alone. We attribute this at least partly to the fact that the contribution of the peptide to the scattering curve was not taken into account.

FIGURE 8.

SAXS analysis of the GBD in complex with collagen. A, ensemble optimization analysis of the GBD alone or in a 1:1 complex with peptide C. Upon complex formation, the Rg distribution narrows through disappearance of minor conformational states. B, schematic representation of 10 SASREF models of the GBD alone (green) or in complex with peptide C (orange). All structures are aligned at the 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI subfragment. Peptide binding does not lead to a major structural rearrangement but stabilizes the pre-existing major conformation.

However, upon complex formation, the breadth of possible GBD conformations narrows through disappearance of minor states. We interpret these data in terms of stabilization of a unique GBD conformation upon collagen binding without further structural rearrangements. This interpretation is supported by an ensemble of 10 SASREF models of the GBD-CC complex, which is highly similar to the ensemble of the GBD alone (Fig. 8B). Once again, there is a 90° kink between 7FnI and 8FnI, and the model displays a slight compaction of 8–9FnI toward the 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI core. Thus, we conclude that cooperative binding of the collagen α2 1/10 site (peptide C) stabilizes a major pre-existing conformation of the GBD in solution. This supports previous findings that FN modules form distinct functional units capable of presenting a unique interface to their respective binding partners (8, 31, 46).

DISCUSSION

We have presented a model showing how the full-length GBD of FN and the most common collagen (type I) interact on a molecular scale. Collagen binding to the GBD is mediated mostly by the 8–9FnI subfragment, which interacts with sites on D-period 1 (1/10 site) and D-period 4 (3/4 site) of both collagen type I chains (26). All four binding sites contain a consensus 9-mer sequence with conserved leucine (position 2) and arginine (position 9) residues acting as major interaction determinants (Fig. 3B) (26). However, not all sites are equal in their affinity for 8–9FnI, with disparities as great as 400-fold between peptides CN and BN.

Our analysis suggests that, in select cases, the remaining GBD subfragment, 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI, can act to reduce this disparity. It had previously been noted that this subfragment binds to gelatin and to short collagen fragments (47, 48), and it had been suggested that 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI can bind triple-helical collagen prior to unwinding (7). Here, we have shown that these domains can also engage a specific collagen site at the 1/10 position of the collagen α2 chain (peptide CC) and increase the overall GBD affinity of that site to levels comparable to those of sites A, B, and D. This is the first collagen interaction found to engage all GBD modules in a cooperative manner, and we speculate that the final physiological result of this additional association is the creation of four broadly equipotent FN-binding sites on collagen type I.

SAXS analysis revealed the GBD to be a relatively elongated particle in solution, the structure of which is characterized by a 90° kink between 7FnI and 8FnI (Figs. 1A and 8B). This GBD kink is matched by a similar change in direction on the collagen peptides studied, which is the result of a local hydrophobic collapse just C-terminal of the core 8–9FnI-binding site (Fig. 7, C and D). Together, these two features create the potential for a snug interaction between collagen and the full-length GBD, a feature exploited by collagen peptide C. GBD modeling from SAXS data of this complex yielded a very similar albeit slightly more compact model than the GBD alone (Fig. 8, A and B). Together with the narrowing of the Rg distribution in the SAXS ensemble analysis, this result indicates that the GBD does not undergo any major conformational changes upon collagen binding. Rather, we propose that the FN GBD adopts in solution a well defined major conformation, which is capable and ready for functional engagement with collagen (17, 49).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. D. Bihan and Prof. R. Farndale for fruitful discussions concerning our work on collagen and for invaluable comments on the manuscript. We thank Drs. Melissa Graewert, Mikail Kachala, and Dimitri Svergun (DESY) and Dr. Adam Round (ESRF) for invaluable support with SAXS data collection. Dr. Pau Bernardo advised us on the ensemble optimization method. We acknowledge DESY and ESRF for provision of synchrotron radiation facilities, including time at beamline ID14-3 for preliminary SAXS measurements. We thank Nick Soffe and Dr. Edward Lowe for maintenance of the NMR and crystallization facilities in the Department of Biochemistry of the University of Oxford and Dr. David Staunton for upkeep of the biophysics facility.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3GXE) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

- FN

- fibronectin

- GBD

- gelatin-binding domain (collagen-binding subfragment of fibronectin)

- SAXS

- small angle x-ray scattering.

REFERENCES

- 1. George E. L., Georges-Labouesse E. N., Patel-King R. S., Rayburn H., Hynes R. O. (1993) Defects in mesoderm, neural tube and vascular development in mouse embryos lacking fibronectin. Development 119, 1079–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leitinger B., Hohenester E. (2007) Mammalian collagen receptors. Matrix Biol. 26, 146–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Campbell I. D., Downing A. K. (1998) NMR of modular proteins. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5, 496–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Erickson H. P., Carrell N., McDonagh J. (1981) Fibronectin molecule visualized in electron microscopy: a long, thin, flexible strand. J. Cell Biol. 91, 673–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leahy D. J., Aukhil I., Erickson H. P. (1996) 2.0 Å crystal structure of a four-domain segment of human fibronectin encompassing the RGD loop and synergy region. Cell 84, 155–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sharma A., Askari J. A., Humphries M. J., Jones E. Y., Stuart D. I. (1999) Crystal structure of a heparin- and integrin-binding segment of human fibronectin. EMBO J. 18, 1468–1479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Erat M.C., Schwarz-Linek U., Pickford A. R., Farndale R. W., Campbell I. D., Vakonakis I. (2010) Implications for collagen binding from the crystallographic structure of fibronectin 6FnI1–2FnII7FnI. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 33764–33770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pickford A. R., Smith S. P., Staunton D., Boyd J., Campbell I. D. (2001) The hairpin structure of the 6F11F22F2 fragment from human fibronectin enhances gelatin binding. EMBO J. 20, 1519–1529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vakonakis I., Staunton D., Ellis I. R., Sarkies P., Flanagan A., Schor A. M., Schor S. L., Campbell I. D. (2009) Motogenic sites in human fibronectin are masked by long range interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 15668–15675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vakonakis I., Staunton D., Rooney L. M., Campbell I. D. (2007) Interdomain association in fibronectin: insight into cryptic sites and fibrillogenesis. EMBO J. 26, 2575–2583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Litvinovich S. V., Strickland D. K., Medved L. V., Ingham K. C. (1991) Domain structure and interactions of the type I and type II modules in the gelatin-binding region of fibronectin. All six modules are independently folded. J. Mol. Biol. 217, 563–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Balian G., Click E. M., Bornstein P. (1980) Location of a collagen-binding domain in fibronectin. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 3234–3236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hynes R. (1985) Molecular biology of fibronectin. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 1, 67–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hynes R. O. (1990) Fibronectins, Springer-Verlag, Berlin [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kleinman H. K., McGoodwin E. B. (1976) Localization of the cell attachment region in types I and II collagens. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 72, 426–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McDonald J. A., Kelley D. G., Broekelmann T. J. (1982) Role of fibronectin in collagen deposition: Fab′ to the gelatin-binding domain of fibronectin inhibits both fibronectin and collagen organization in fibroblast extracellular matrix. J. Cell Biol. 92, 485–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kadler K. E., Hill A., Canty-Laird E. G. (2008) Collagen fibrillogenesis: fibronectin, integrins, and minor collagens as organizers and nucleators. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20, 495–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Engvall E., Ruoslahti E. (1977) Binding of soluble form of fibroblast surface protein, fibronectin, to collagen. Int. J. Cancer 20, 1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dessau W., Adelmann B. C., Timpl R. (1978) Identification of the sites in collagen α-chains that bind serum anti-gelatin factor (cold-insoluble globulin). Biochem. J. 169, 55–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blumenstock F. A., La Celle P., Herrmannsdoerfer A., Giunta C., Minnear F. L., Cho E., Saba T. M. (1993) Hepatic removal of 125I-DLT gelatin after burn injury: a model of soluble collagenous debris that interacts with plasma fibronectin. J. Leukoc. Biol. 54, 56–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. La Celle P., Blumenstock F. A., McKinley C., Saba T. M., Vincent P. A., Gray V. (1990) Blood-borne collagenous debris complexes with plasma fibronectin after thermal injury. Blood 75, 470–478 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Egeblad M., Werb Z. (2002) New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 161–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leikina E., Mertts M. V., Kuznetsova N., Leikin S. (2002) Type I collagen is thermally unstable at body temperature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 1314–1318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fiori S., Saccà B., Moroder L. (2002) Structural properties of a collagenous heterotrimer that mimics the collagenase cleavage site of collagen type I. J. Mol. Biol. 319, 1235–1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stultz C. M. (2002) Localized unfolding of collagen explains collagenase cleavage near imino-poor sites. J. Mol. Biol. 319, 997–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Erat M. C., Slatter D. A., Lowe E. D., Millard C. J., Farndale R. W., Campbell I. D., Vakonakis I. (2009) Identification and structural analysis of type I collagen sites in complex with fibronectin fragments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 4195–4200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Iyer S., Visse R., Nagase H., Acharya K. R. (2006) Crystal structure of an active form of human MMP-1. J. Mol. Biol. 362, 78–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bingham R. J., Rudiño-Piñera E., Meenan N. A., Schwarz-Linek U., Turkenburg J. P., Höök M., Garman E. F., Potts J. R. (2008) Crystal structures of fibronectin-binding sites from Staphylococcus aureus FnBPA in complex with fibronectin domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 12254–12258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schwarz-Linek U., Werner J. M., Pickford A. R., Gurusiddappa S., Kim J. H., Pilka E. S., Briggs J. A., Gough T. S., Höök M., Campbell I. D., Potts J. R. (2003) Pathogenic bacteria attach to human fibronectin through a tandem β-zipper. Nature 423, 177–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Graille M., Pagano M., Rose T., Ravaux M. R., van Tilbeurgh H. (2010) Zinc induces structural reorganization of gelatin binding domain from human fibronectin and affects collagen binding. Structure 18, 710–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vakonakis I., Campbell I. D. (2007) Extracellular matrix: from atomic resolution to ultrastructure. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19, 578–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Millard C. J., Campbell I. D., Pickford A. R. (2005) Gelatin binding to the 8F19F1 module pair of human fibronectin requires site-specific N-glycosylation. FEBS Lett. 579, 4529–4534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vakonakis I., Langenhan T., Prömel S., Russ A., Campbell I. D. (2008) Solution structure and sugar-binding mechanism of mouse latrophilin-1 RBL: a 7TM receptor-attached lectin-like domain. Structure 16, 944–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Leslie A. G. W., Powell H. R. (2007) Processing diffraction data with MOSFLM. in Evolving Methods for Macromolecular Crystallography (Read R. J., Sussman J. L., eds) pp. 41–51, Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 35. Evans P. (2006) Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 72–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zwart P. H., Afonine P. V., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Hung L. W., Ioerger T. R., McCoy A. J., McKee E., Moriarty N. W., Read R. J., Sacchettini J. C., Sauter N. K., Storoni L. C., Terwilliger T. C., Adams P. D. (2008) Automated structure solution with the PHENIX suite. Methods Mol. Biol. 426, 419–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Adams P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Hung L. W., Ioerger T. R., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Read R. J., Sacchettini J. C., Sauter N. K., Terwilliger T. C. (2002) PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1948–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Krissinel E., Henrick K. (2007) Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Konarev P. V., Volkov V. V., Sokolova A. V., Koch M. H. J., Svergun D. I. (2003) PRIMUS: a Windows PC-based system for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Cryst. 36, 1277–1282 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Svergun D. I. (1992) Determination of the regularization parameter in indirect-transform methods using perceptual criteria. J. Appl. Cryst. 25, 495–503 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bernadó P., Mylonas E., Petoukhov M. V., Blackledge M., Svergun D. I. (2007) Structural characterization of flexible proteins using small-angle x-ray scattering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 5656–5664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Petoukhov M. V., Svergun D. I. (2005) Global rigid body modeling of macromolecular complexes against small-angle scattering data. Biophys. J. 89, 1237–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Svergun D. I., Barberato C., Koch M. H. J. (1995) CRYSOL–a program to evaluate x-ray solution scattering of biological macromolecules from atomic coordinates. J. Appl. Cryst. 28, 768–773 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Petroukhov M. V., Konarev P. V., Kikhney A. G., Svergun D. I. (2007) ATSAS 2.1–towards automated and web-supported small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Cryst. 40, s223–s228 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Atkin K. E., Brentnall A. S., Harris G., Bingham R. J., Erat M. C., Millard C. J., Schwarz-Linek U., Staunton D., Vakonakis I., Campbell I. D., Potts J. R. (2010) The streptococcal binding site in the gelatin-binding domain of fibronectin is consistent with a non-linear arrangement of modules. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 36977–36983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Katagiri Y., Brew S. A., Ingham K. C. (2003) All six modules of the gelatin-binding domain of fibronectin are required for full affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11897–11902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pagett A., Campbell I. D., Pickford A. R. (2005) Gelatin binding to the 6F11F22F2 fragment of fibronectin is independent of module-module interactions. Biochemistry 44, 14682–14687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Holmes D. F., Tait A., Hodson N. W., Sherratt M. J., Kadler K. E. (2010) Growth of collagen fibril seeds from embryonic tendon: fractured fibril ends nucleate new tip growth. J. Mol. Biol. 399, 9–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]