Abstract

The BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill was enormously newsworthy; coverage interlaced discussions of health, economic, and environmental impacts and risks. We analyzed 315 news articles that considered Gulf seafood safety from the year following the spill. We explored reporting trends, risk presentation, message source, stakeholder perspectives on safety, and framing of safety messages. Approximately one third of articles presented risk associated with seafood consumption as a standalone issue, rather than in conjunction with environmental or economic risks. Government sources were most frequent and their messages were largely framed as reassuring as to seafood safety. Discussions of prevention were limited to short-term, secondary prevention approaches. These data demonstrate a need for risk communication in news coverage of food safety that addresses the larger risk context, primary prevention, and structural causes of risk.

The British Petroleum (BP) Deepwater Horizon oil spill (“the oil spill”) in the Gulf of Mexico was the largest offshore oil spill in US history.1 This event presented interlaced threats to local economies, fisheries, sensitive habitats and human health. From the oil spill’s start on April 20, 2010, to the near complete reopening of fishing waters on November 15, 2010, news coverage was extensive and generated greater reader interest than other leading news stories.2 Somewhat astonishingly, for the first 100 days, oil spill coverage accounted for 22% of the US newshole (space given to news content)2; 1 survey found that up to 50% to 60% of respondents followed the story “very closely.”2

The present study explores the ways in which the safety of seafood for human consumption was presented amid other seafood-related risks in US print news media coverage of the oil spill. News coverage is a key source through which the public learns about health risks,3,4 particularly during heightened awareness situations. In assessing the messages about seafood safety, we address the dynamics and multiple potential functions5 of risk communication in print media. The news media as a social institution frequently stands apart from those that bear responsibility for the creation and management of risk and make risks perceptible to the public.3 Instead, the news media select among possible expert and lay sources, each which could have different interpretations of the issue at hand.6 To these sources, journalists contribute their own frames to create a story while also responding to deadlines, resource constraints, and sales pressures.3,7

As a medium for risk communication in a politically sensitive contamination event such as the BP oil spill, news coverage faces potential extremes: downplaying food risk to avoid local economic fallout and therefore underinforming the public, focusing only on technical risk assessment and avoiding the many other interpretations of risk, or stigmatizing the domestic or regional seafood supply by highlighting dangers.8

If long-range effects of media coverage are important, then the function of risk communication becomes more than the immediate avoidance of a hazard.5 Risk communication via the news media may also influence how the public understands direct and indirect causes of a risk issue. If the larger context of risk is highlighted, the various publics may pursue opportunities to engage in prevention via policy or structural means.9

To assess (1) the newsworthiness of seafood safety, (2) factors potentially shaping public perception of risk, and (3) short- and long-term risk messaging about Gulf seafood safety, we examined coverage volume across various news outlets, the sources referenced in the stories, reference to cause, and depth of risk information provided in news coverage of the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. In particular, we examine how health messages presented in the news media reflect the complex interplay of economic, environmental, and health concerns. We address the following 4 questions: (1) How and where are human health threats of fish consumption being discussed as part of the oil spill news coverage?; (2) Do health risks associated with eating Gulf seafood appear alone or are they paired with other oil spill related risks?; (3) When an article includes a quote about seafood safety, who is the source and how does that source frame issues of seafood safety?; and finally (4) What parties are identified as responsible for ensuring seafood safety after the oil spill?

The oil spill story is complex. Rather than a single narrative, it is perhaps better understood as numerous, intertwined news threads. These include issues such as the human tragedy of the explosion, ecological damage, future of the Gulf economy, energy policies, industrial regulation, cultural impacts, and the health consequences. In a report detailing the 3 main human health threats from the oil spill, seafood safety was identified along with direct oil contact and mental health issues.10 Consuming oil-contaminated seafood increases exposure to carcinogens known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)11 or dispersants.12,13

Seafood safety presents a unique dimension of risk communication in the oil spill. Many direct health threats associated with the oil spill are local, whereas the public health implications of seafood safety have both local and national impact. Though Gulf residents consume more seafood than the national average,14 Gulf seafood is sold and consumed throughout the United States. Ninety percent of the crawfish, 70% of shrimp, and 69% of oysters caught in the United States come from the US Gulf Coast fisheries.15 Some of the main Gulf seafood exports—shrimp, crab, and oysters—are more vulnerable to PAHs than other seafood because their systems are less able to clear these contaminants.11,16

Certain types of seafood come predominantly from the Gulf, overall, but only 16% of the US seafood supply is sourced from the Gulf of Mexico.17 From a national perspective, consumers may assume information about the Gulf oil spill applies to most of their seafood, and this misunderstanding could change seafood purchasing accordingly. Alternatively, the attention to domestic seafood risk could cause consumers to lose sight of concerns about imported seafood, such as the risk of contamination with antimicrobial drugs,18 rather than making a more rational and informed calculus.

Finally, the messages on seafood safety evolved over time moving from more to less uncertainty regarding actual rather than feared contamination with PAHs. According to 2 studies, ultimately the exposure risk posed to humans from oil- or dispersant-contaminated seafood in the Gulf was low.13 Readings from approximately 8000 seafood samples for 13 individual carcinogenic PAHs and a dispersant

were found in low concentrations or below the limits of quantitation. When detected, the concentrations were at least two orders of magnitude lower than the level of concern for human health risk.19(p4)

Although the findings show minimal seafood contamination, the US Food and Drug Administration has been criticized for problematic exposure assessment in terms of underestimating human seafood consumption levels, not applying sufficient safety margins for children’s consumption, and overestimating body weight when considering exposure.11,16,20 The evolving nature of the data on seafood contamination and challenges to the assessment process underscore the uncertainty involved in terms of what messages could and should be communicated to whom at what point.

From a public health perspective, the news media’s communication about seafood as a risky or healthy food source in the context of the oil spill is particularly relevant. Not only is the safety of Gulf seafood a standalone public health concern, but risk messages can also be detrimental if they disproportionately amplify concern and thus discourage consumption of seafood in general.21 Similarly, insufficient discussion of risk does not adequately inform consumers for their food choices. The quality of Gulf seafood is closely entwined with the economic and environmental future of the Gulf. Local reporting of seafood risk becomes a potentially delicate matter of gauging health and economic impacts. Finally, the extent to which these 3 risks (economic, environmental, and health) were reported as linked was of interest as the connections between environmental concerns and food systems concerns have not always been adequately addressed in the news media, missing an opportunity to detail the path from environmental problems to human health challenges.22

METHODS

We collected print news coverage of the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill that mentioned seafood and risk for the 6 months following the oil spill (April 20—October 20, 2010) and for the 4 weeks surrounding the 1-year anniversary, from April 1 to April 30, 2011. During this April 2011 timeframe, the FDA and NOAA reopened the last of the affected federal fisheries for commercial fishing.23 Our news sample included 7 news sources, selected for their circulation or reach, as well as proximity to the oil spill and accessibility via LexisNexis Academic. Three were local newspapers from the Gulf of Mexico (St. Petersburg Times [Florida], Louisiana Times-Picayune, Mobile Register [Alabama]), 3 were national newspapers (New York Times, Washington Post, and USA Today), and 1 was a national news wire service (Associated Press). Our final search string follows: (seafood or fish or oysters or shrimp) AND (contaminat* or taint* or test* or safe*) AND (oil spill). News stories, event announcements, letters to the editor, columns, and editorials were included in the resulting sample.

Codebook Development

The codebook was based on the 4 research questions presented in the introduction, and was initially developed by 2 authors (N. S. and K. C. S.). Refinement of the coding schema was achieved by 4 additional authors (A. L. G., L. P. L., R. A. N., and D. C. L) jointly coding 19 of articles followed by repeated consensus-building discussions. Our coding variables included headline (free text), date of publication, news source, type of fish mentioned, type of risk mentioned, connection made between ecological harm and human health, mention of seafood health benefits, mention of means of avoiding risk from contaminated seafood, government policy interventions to minimize risk, mention of BP or other party responsibility for seafood safety, perspectives on seafood safety and oil industry, and message valence.

Analytic Coding

The 556 articles from LexisNexis were divided evenly among the 4 coders, and each article was reviewed by a single coder. Coding focused only on manifest content explicitly stated in the article, rather than also including more subjective or latent codes. Articles were noted as “not relevant” and excluded from further analysis if they contained less than 2 sentences discussing the oil spill’s impacts on seafood as a human food source (including economic, environmental, cultural, or human health concerns). We excluded articles focused on biologic and ecologic impacts of oil and dispersants to marine life. Based on these exclusion criteria, 315 articles were included for further analysis.

Interrater Reliability and Inclusion of Variables

In conjunction with the analytic coding, 2 additional rounds of coding (18 articles in each set) by all coders were undertaken to (1) assess agreement and reliability across the 4 coders and (2) compare reliability over the span of the project. The first round of reliability coding occurred prior to the analytic coding of the full sample; the second was conducted near the end of the analytic coding.

We used Stata version 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) to calculate Intraclass Correlation Coefficient case 3, 1 judge (ICC (3,1)) for each variable of interest.24 Because this coding process did not result in each article receiving a single summary score, the ICC provides a reliability measure for each variable of interest, but not an overall reliability score. This measure assesses reliability and agreement among a fixed set of raters for a specific data set (in this case, news articles). This particular measure accounts for the variation that will occur when, for the full analysis, each article would be assessed by exactly 1 of the 4 raters who participated in the reliability study. Additionally, to account for variables with insufficient levels of variance in order for the ICC calculations to be useful, we also calculated percent agreement.

ICC scores from 0.5 to 0.75 indicate moderate agreement.25 Those variables that achieved either 65% agreement or an ICC score of 0.5 by the second round of reliability coding were included for analysis. Our percent agreement ranged from 0.64 to 1; our ICC (3,1) scores ranged from 0 to 0.79, with many of the lower scores reflecting insufficient variation in answers to yes or no questions for a meaningful score. The only variable that was excluded from further analysis was the “fishing-related policy recommendations” as it did not achieve sufficient reliability or agreement scores.

Analysis

Data analysis of the final 315 articles was performed using Stata version 11. To analyze change in key variables over time, we grouped the data into 4 time periods (below) based on the evolution of the oil spill and fishery closures and reopenings. These time periods were selected to break up reporting into theoretically meaningful divisions, and are not of equal length, nor do they include consistent numbers of articles. Comparisons across these time periods are made in terms of proportions or weekly average article count, and not raw counts.

April 20–June 2, 2010: Oil spill begins—start of spill until fishery closures reach maximum;

June 3–July 21, 2010: Getting control of the spill—includes maximum fishery closures, capping the well on June 15, and the day before first major reopening of federal waters for fishing;

July 22–Oct 20, 2010: Federal waters opening—includes reopening of some federal waters until 6 months after the oil spill;

April 1–April 30, 2011: One-year anniversary comparison—includes the month surrounding 1-year anniversary of oil spill and opening of a commercial fishery in Louisiana (April 11), largest fishery opening announcement since November 15, 2010.23,26

To understand how our different sources presented seafood risk and safety messages, we first calculated the odds that each source (e.g., government representative, independent evaluator) would frame its message in terms of risk or uncertainty. We examined how articles addressed responsibility for seafood safety by evaluating what percentage of articles made any statements about responsibility. Then, among those articles we calculated the frequency that each of 6 possible parties (federal government, local or state government, business, consumers, oil industry, and NGOs) was implicated. Further analysis addressed how health was prioritized in the articles and trends in co-occurrence of discussion of health risks with other risks. Our qualitative analysis included 3 considerations of risk presentation: how risk appeared in headlines, types of seafood safety messages that different sources were presenting and how those messages were framed, and comparing how “risk/uncertainty” messages differed from “reassurance” or “neutral” messages.

RESULTS

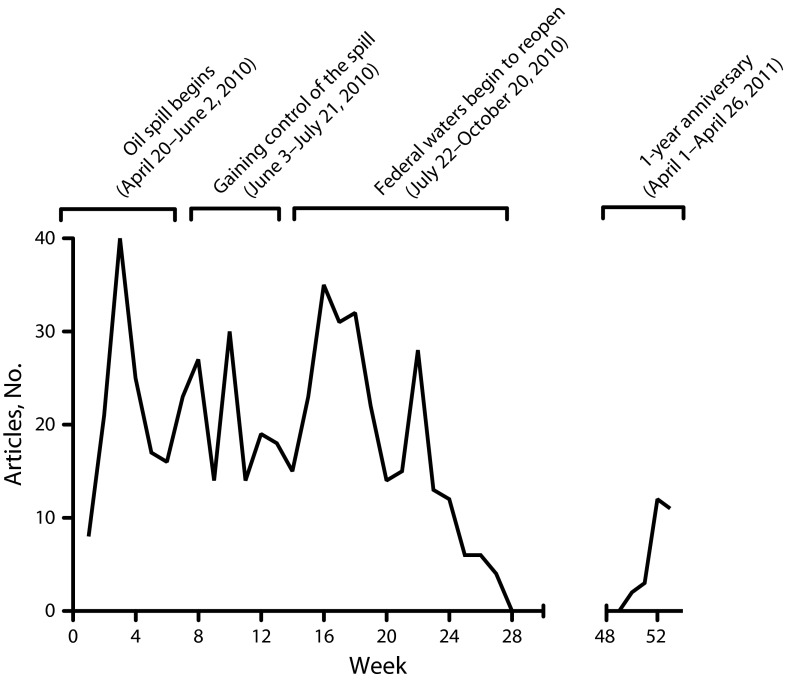

Our Lexis-Nexis search resulted in 556 articles, 315 of which met our inclusion criteria. The majority of news coverage relevant to the impact of the oil spill on seafood was observed during the initial stages of the disaster and early attempts to gain control of the spill (Figure 1), indicating that the newsworthiness of seafood safety ebbed over time. Coverage dropped off steadily as the authorities gained control over the spill and federal fishing waters began to reopen. Relatively few seafood articles were published during the month marking the disaster’s 1-year anniversary (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Volume of seafood-related newspaper coverage connected with the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill: April 20, 2010–April 26, 2011.

Note. First 6 months of coverage and the month around the 1-year anniversary of the oil spill were monitored.

The source with the highest volume of pertinent articles was the Mobile Register (n = 109, 35%), followed by the Associated Press (n = 99, 31%), The Times-Picayune (n = 69, 22%), the New York Times (n = 15, 5%), the St. Petersburg Times (n = 14, 4%), USA Today (n = 6, 2%), and the Washington Post (n = 3, 1%; Table 1). Thus, 192 articles (61%) were classified as “local” and 123 articles (39%) were drawn from “national” news sources.

TABLE 1—

Summary Statistics of Seafood-Related Newspaper Coverage of the British Petroleum (BP) Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill by Newspaper: April 20, 2010–April 26, 2011

| Variable | Times-Picayune (n = 69), No. (%) | Mobile Register (n = 109), No. (%) | St. Petersburg Times (n = 14), No. (%) | New York Times (n = 15), No. (%) | Associated Press (n = 99), No. (%) | Washington Post (n = 3), No. (%) | USA Today (n = 6), No. (%) |

| Region | Local | Local | Local | National | National | National | National |

| Seafood type mentioneda | |||||||

| “Seafood” | 49 (71.0) | 56 (51.4) | 9 (64.3) | 7 (46.7) | 56 (56.6) | 2 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| Finfish | 28 (40.6) | 69 (63.3) | 9 (64.3) | 7 (46.7) | 55 (55.6) | 1 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) |

| Crustaceans and mollusks | 42 (60.9) | 79 (72.5) | 7 (50.0) | 12 (80.0) | 62 (62.6) | 3 (100) | 6 (100.0) |

| Health in the headline | 14 (20.3) | 32 (29.4) | 2 (14.3) | 0 | 19 (19.2) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) |

| Health benefits of seafood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Types of riska | |||||||

| None | 3 (4.3) | 2 (1.8) | 0 | 0 | 6 (6.1) | 0 | 1 (16.7) |

| Environmental | 24 (34.8) | 32 (29.4) | 1 (7.1) | 5 (33.3) | 28 (28.3) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) |

| Economic | 52 (75.4) | 49 (45.0) | 10 (71.4) | 13 (86.7) | 52 (52.5) | 3 (100) | 4 (66.7) |

| Health—seafood in general | 2 (2.9) | 0 | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 2 (2.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Health—Gulf seafood | 48 (69.6) | 88 (80.7) | 8 (57.1) | 9 (60.0) | 69 (69.7) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) |

| Response to health risksa | |||||||

| Individual means | 2 (2.9) | 13 (11.9) | 2 (14.3) | 0 | 10 (10.1) | 1 (33.3) | 0 |

| Food safety policies | 31 (44.9) | 68 (62.4) | 5 (35.7) | 4 (26.7) | 49 (49.5) | 2 (66.7) | 4 (66.7) |

| Other policies | 14 (20.3) | 15 (13.8) | 4 (28.6) | 4 (26.7) | 31 (31.3) | 0 | 1 (16.7) |

| Parties implicated as responsible for seafood safety | |||||||

| Consumers | 2 (2.9) | 6 (5.5) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Business | 8 (11.6) | 3 (2.8) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (6.7) | 6 (6.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Federal government | 32 (46.4) | 62 (56.9) | 5 (35.7) | 7 (46.7) | 58 (58.6) | 2 (66.7) | 4 (66.7) |

| State/local government | 24 (34.8) | 44 (40.4) | 4 (28.6) | 4 (26.7) | 33 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (33.3) |

| Oil companies in general | 5 (7.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 0 |

| BP specifically | 11 (15.9) | 5 (4.6) | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 10 (10.1) | 0 | 2 (33.3) |

| Distribution by time period | |||||||

| April 20–June 2, 2010 | 17 (24.6) | 21 (19.3) | 4 (28.6) | 1 (6.7) | 25 (25.3) | 0 | 1 (16.7) |

| June 3–July 21, 2010 | 21 (30.4) | 21 (19.3) | 5 (35.7) | 7 (46.7) | 22 (22.2) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (16.7) |

| July 22–November 30, 2010 | 29 (42.0) | 58 (53.2) | 5 (35.7) | 6 (40.0) | 51 (51.5) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (50.0) |

| April 2011 | 2 (2.9) | 9 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 1 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (16.7) |

Note. First 6 months of coverage and the month around the 1-year anniversary of the oil spill were monitored.

Response categories for items 2, 5, 6 were not mutually exclusive; values may total more than 100%.

Table 1 provides summary data on the nature of the articles’ discussion around seafood, the context in which messages about seafood risk appeared, the extent to which health was identified as a relevant consideration, and the risk management strategies discussed.

Discussion of Health in the Context of the Oil Spill

To assess the prominence of seafood safety as a health concern, we examined the frequency with which this topic appeared as a headlining issue (in addition to the article text). Health concerns first appeared in these newspapers approximately 2 weeks after the start of the spill in the article headline and text. The first was a Times-Picayune article on May 1, 2010, under the headline “State shuts down fishing east of Mississippi River; Jindal, federal officials losing patience with BP efforts to control oil.”27 The next day, seafood safety again made headlines in the Times-Picayune: “Crisis in Gulf eating at seafood lovers, restaurants; eateries stress fish being served is safe.”28 Other seafood safety headlines included:

“US works to assure public Gulf seafood is safe,”29

“Seafood tests underway, Pas lab is testing seafood,”30

“Trained noses to sniff out Gulf seafood for oil,”31

“Festivals offer tasty (and safe) seafood,”32

“Gulf seafood declared safe; fisherman not so sure,”33 and

“Seafood testing goes on.”34

Seafood safety and associated health concerns was more newsworthy (as assessed by proportion of headlines) in local rather than national newspapers (Table 1). For both national and local newspapers, however, the issue of seafood safety never headlined in more than a third of the articles.

Discussing Health Risks of Gulf Seafood

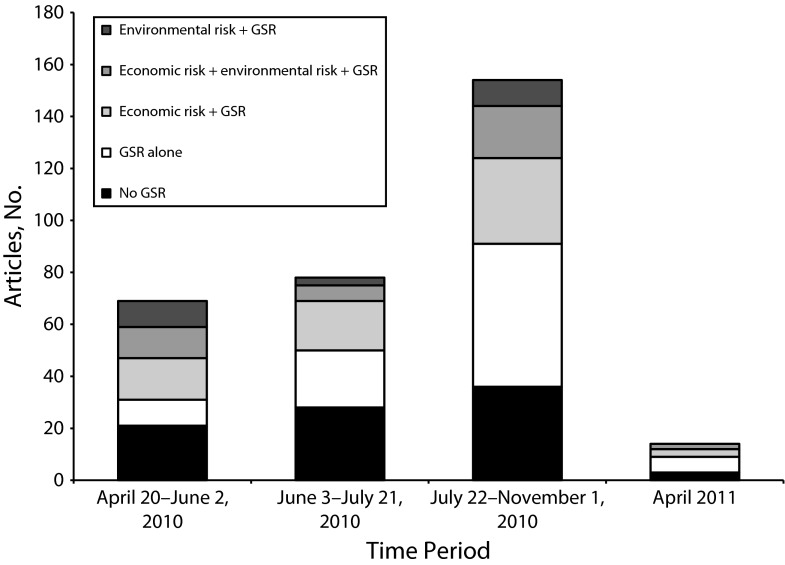

As presented in Figure 2, we evaluated whether health risk associated with Gulf seafood (labeled GSR for “Gulf seafood risk”) appeared alone (GSR only), with other risks (GSR+Environment; GSR+Economic; GSR+Environment+Economic), or not at all (No GSR).

FIGURE 2—

Number of seafood-related newspaper articles connected with the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill, by oil spill stage: April 20, 2010–April 26, 2011.

Note. GSR = Gulf Seafood Risk. Raw counts were used to preserve comparison of volume differences among time periods, note that the third time period involves several months and the others, 4–6 weeks. First 6 months of coverage and the month around the 1-year anniversary of the oil spill were monitored. Those articles marked as “no gulf seafood risk” included those that mentioned seafood and risk, but the risks discussed were not connected to seafood.

Approximately three quarters of the articles in the sample included some discussion of potential health risks associated with consuming Gulf seafood following the oil spill (n = 227, 72.1%), and in more than one quarter (n = 93, 29.5%) human health was the only risk discussed. Approximately 40% of articles discussed threats to human health in conjunction with at least one other risk (i.e. economic, environment). The number and proportion of articles that covered Gulf seafood and human health concerns as a stand-alone issue increased over time, indicating that this topic was newsworthy in its own right, (though overall coverage of seafood issues was decreasing).

We examined the extent to which articles presented strategies by which individuals could avoid health threats from eating oil- or dispersant-tainted seafood. Such strategies could include smelling the fish for oil or asking vendors about location of origin. Across the entire sample, only 28 articles (8.9%) provided guidance on how to avoid risk, with more frequent discussion in local newspapers (7.6%–10.6% across time periods) than national sources, which ranged from no coverage to 12.9% coverage (1 of the 7 national articles) in the final time period. To understand the context of risk messages, we coded the articles for any mention of benefits of eating seafood (ω-3 fatty acids, healthy protein source). No article in the sample made any mention of benefits associated with seafood consumption, Gulf or otherwise.

Another question was the extent to which articles mentioned policy approaches to address seafood safety concerns (Table 1). Across the 7 news outlets, policies relevant to food safety and testing were discussed more often than other potential policy solutions; this contrast was greatest for local newspapers. For example, 62.4% of articles collected from the Mobile Register mentioned food safety and testing policies, although 13.8% discussed other policies.

Stakeholder Perspectives Regarding Seafood Safety

The news articles incorporated more than 1 dimension of risk and often a variety of perceptions. A considerable majority of articles cited at least 1 stakeholder (n = 231, 73.3%) quoting his or her perspective on seafood safety. There were distinct trends in how these stakeholders framed issues concerning seafood safety (Table 2).

TABLE 2—

Odds of Framing Seafood Safety Messages as Reassuring, Risky or Neutral and Message Frequency by Source: April 20, 2010–April 26, 2011

| Source | Odds of Reassurance Frame Over Other | Odds of Neutral Frame Over Other | Odds of Risk Frame Over Other | Times Quoted as First or Second Source, No. | Total Quotes, % |

| Federal government | 3.94 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 84 | 27.1 |

| Marketing group | 3.80 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 24 | 7.7 |

| State/local government | 3.25 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 68 | 21.9 |

| Fishing industry | 0.73 | 0.00 | 1.38 | 38 | 12.3 |

| Gulf business | 0.57 | 0.06 | 1.40 | 36 | 11.6 |

| Other (academic) | 0.50 | 0.06 | 1.18 | 24 | 7.7 |

| Gulf resident | 0.44 | 0.00 | 2.25 | 13 | 4.2 |

| Fisherman | 0.38 | 0.00 | 2.63 | 29 | 9.4 |

| Independent evaluator | 0.36 | 0.00 | 2.75 | 15 | 4.8 |

| BP | …a | …a | …a | 3 | 1.0 |

Note. BP = British Petroleum.

The small number of BP representatives quoted provides limited data to sufficiently calculate the odds.

We conducted a Pearson’s χ2 analysis to assess whether government sources varied in message framing from all other sources. The federal, state and local sources were statistically significantly different from the other sources in the framing of seafood safety messages (χ2 = 84.105; P < .001).Governmental representatives (both federal and local or state), along with marketing professionals, had the highest odds of putting forth messages about reassurance and safety. For example, Jane Lubchenco, administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, said “We’re taking extraordinary steps to assure a high level of confidence in the seafood.”35

Still, Don Kraemer, who is leading FDA’s Gulf seafood safety efforts, said the government is not relying on testing alone.

We couldn’t possibly have enough samples to make assurances that fish is safe. The reason we have confidence in the seafood is not because of the testing, it’s because of the preventive measures that are in place, [such as fishing closures].36

By contrast, independent evaluators, members of the fishing industry, and Gulf business owners, residents, and fishermen were more likely to be quoted discussing seafood safety in terms of risk. Examples of messages about seafood safety with risk frames include the following, 1 from a fisherman and 1 from a Gulf resident:

In Pass Christian, Mississippi, 61-year-old Jimmy Rowell, a third-generation shrimp and oyster fisherman, worked on his boat at the harbor and stared out at the choppy waters. “It’s over for us. If this oil comes ashore, it’s just over for us,” Rowell said angrily, rubbing his forehead. “Nobody wants no oily shrimp.”37

“Normally, I would go to the casinos and eat seafood, but now I’m going to be kind of skeptical of eating,” said Samuel Washington, 44, who lives in Norfolk, Va., but also owns a home in Ocean Springs. “My biggest concern is whether they are really testing all the affected areas.”38

Responsibility for Seafood Safety

We sought to understand whether and how the news articles allocated responsibility for addressing seafood safety after the oil spill; 218 articles (69.2%) identified a specific responsible party. Generally, 1 or 2 responsible parties were identified per article (out of a possible 7), with federal and local or state governmental representatives most often mentioned (52.5% and 34.6%, respectively). Articles in national sources gave more attention to the Federal government in this regard, whereas local sources gave relatively more attention to local or state governments.

We also included a specific question about BP’s role and found that few articles specifically identified BP as being responsible for safety following the oil spill (n = 29; 9.2%). The proportions of local versus national newspapers indicating BP as being responsible for seafood safety were similar (8.3% vs 10.6%, respectively). A small proportion of articles identified businesses (5.9%), consumers or the public (3.4%), or some other party (3.7%) as being responsible for addressing seafood safety following the oil spill.

Linking Human Health and Ecological Disasters

We examined how widely the articles might acknowledge that ecological disruptions could indirectly affect human health and found that only a small portion (n = 16; 5.1%) of articles explicitly made this linkage. A slightly greater proportion of local newspapers (6.3%) made this connection versus national sources (3.3%), and only local articles considered this a newsworthy issue during the first time period.

DISCUSSION

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill dominated US media coverage for months and sustained the public’s interest at nearly unprecedented levels.39 We examined a subset of that coverage in selected local and national newspapers, including articles that dealt with some dimension of seafood and associated risks. The analysis identified varying levels of attention to seafood safety across news outlets, with greater and somewhat more detailed coverage in local than national sources. We found that coverage often lacked a public health perspective, providing inadequate context and information about different levels of prevention. This finding raises questions about what ultimate function(s) mentioning seafood risk is meant to serve.5 The analysis found both that media coverage addressed many perspectives of risk3 and that striking differences existed in how seafood safety messages were framed by different quoted stakeholders, with governmental spokespeople particularly likely to communicate reassurance. The study thus sparks questions about the impacts of this risk communication and suggests several potential targets for public health expert guidance to improve reporting on food-related risk.

Extent of Coverage

Media coverage of seafood safety began soon after the oil spill. The issue’s appearance in the weeks following the explosion is an important indicator of newsworthiness, particularly in light of competing storylines highlighting the explosion itself and efforts to cap the well. As one might predict, over the study period, the proportion of articles discussing seafood safety increased, both because attention turned from crisis to a more considered analysis of potential implications and because of a drive to pursue new angles. The study found more than 50% more articles mentioning seafood safety in the local than the national newspapers sampled. This may be appropriate, as consumers in the region eat more Gulf seafood than do others,14,20 and these are the groups that are most interacting with the multiple dimensions of risk the oil spill presents. However, the national nature of the food supply means risks do not remain localized. Although not representative, our sample indicates that newspaper readers likely encountered different risk messages depending on where they lived and whether they read local or national newspapers. As a headlining issue, seafood safety never appeared in more than one third of either local or national headlines in our sample. It is possible that this and the smaller proportion of articles that address seafood safety as a standalone issue represent some form of underreporting, potentially motivated by the sensitivity to the fragility of the Gulf economy. This level of reporting about seafood safety may also be a reflection of the many other pressing concerns as part of the oil spill.

Discussion of Health Risks

Discussion of health risks associated with eating Gulf seafood was frequently paired with discussion of environmental and economic risks rather than being treated as a standalone issue. This pairing is not surprising given the role the environment plays in seafood quality and the impact that contaminated seafood could have on the Gulf region’s economy. Although various risks were often presented in a single story, explicit linkages—causal or otherwise—between environmental and human health problems were relatively rare, particularly in the national sources. Indeed, a growing body of literature suggests that connections between policy and human and ecological health are not always fully addressed by the media.9,22 In addition, although seafood safety as a standalone issue did not predominate, it did increase over time (Figure 2), explained in part by the opening of fisheries for sales nationally and the growing availability of data on the level of contamination labs found in the fish.13

Framing Seafood Safety

One of the more surprising findings was the differentiation in risk and reassurance message framing between government sources and others, particularly Gulf residents. These differences highlight 3 dynamics at play when risk communication and new coverage intersect: (1) the existence of multiple, often competing dimensions of risk perception, (2) journalists’ choices about which perspectives to relay, and (3) the possibility that controversy or disagreement is emphasized to maximize newsworthiness. The consistency of reassurance framing in government messaging suggests a purposeful strategy. Indeed, government messages conveyed reassurance about the sufficiency of the process and the safety of the seafood even from the beginning when there was little information available about actual risk40,41; as fishing restrictions and seafood testing programs were implemented, such positively-valenced messaging continued.42 The federal and state governments’ interest in conveying reassurance may stem from a desire to reduce anxiety in the context of a fragile economy, confidence in the risk-reduction measures available, an effort to increase confidence in government in the lead-up to midterm elections, or an interest in reducing outrage at government regulators. This approach may, however, have negative implications for trustworthiness if the messages do not seem complete nor to adequately attend to stakeholders’ concerns.7 Uncertainty is a challenge in terms of effective mass communication, particularly during periods of fast paced change, but must be appropriately managed if public trust is to be maintained.43

News coverage is a product of collective social action in which both journalists and stakeholders serve as influential actors. Thus, any consistent reassurance message regarding seafood safety involves not only governmental accounts but also media acquiescence with such a position. Ungar provides an explanation for such actions in times of great uncertainty and potential crisis, where journalists and other agenda setters prioritize maintenance of established order, rather than building fear.44 Similarly, journalists, even though limited by resources and time, have a choice about whether to engage critically with risk messages provided by different sources.3

The fishing industry exhibited the most temporal variation in message framing, with a slight likelihood of reassurance framing in the first time set and moving sharply to a risk frame in the second and third. Spokespeople may have changed their framing as it became clear that the industry faced more long-term risk from consumer outrage if the public felt it was being falsely reassured about unsafe seafood. In other words, those associated with the fishing industry walked both sides of the “risk” line: on one hand, sufficient concern about seafood needs to exist to garner support to help the industry and fishing-related business cannot survive if contaminated supplies make it into the food chain. On the other hand, exaggerated concerns about seafood safety are also damaging to demand for Gulf seafood.

What does it mean when there is such a consistent difference in reaction to a topic such as seafood safety? Certainly the interests and experience of each stakeholder group would lead them to perceive and react to seafood safety differently. Federal and state governments combined strong precautionary actions (fishery closures, widespread testing) and reassurance-framed messages. These messages often lacked sufficient context to fully inform, and this imbalance has perhaps contributed to existing concern among those most immediately affected. Journalists may also routinely include statements from officials, and would then seek differently framed statements either for balance or even with the aim of presenting controversy. It should be emphasized that this discussion of framing reflects the statements’ overall tone and does not necessarily reflect differences in beliefs about the actual safety of the seafood; this coding aims to assess the emotional tenor around different sources discussions of seafood safety in the news media.

Prevention at the Individual and Policy Level

From a public health perspective, 2 findings around prevention messages are particularly noteworthy. Both raise questions about the function of risk communication efforts in the reporting of complex disasters. First, we were surprised to find that no article in our sample mentioned the benefits of eating seafood, important context to counteract avoidance of an entire food group. Notably, very few mentioned what consumers or businesses should look for when purchasing or catching seafood to avoid risk. The Environmental Protection Agency has noted that informing individuals about what they can do to avoid risk is perhaps the most important function of risk communication.7(p3) At the policy level, reporting primarily focused on the most proximal issues related to seafood safety—testing and inspection policies. There was little discussion about the larger context of prevention—how drilling practices and societal demands for oil can link to these kinds of environmental, economic, and health disasters, which in turn threaten seafood. To be fair, the media did provide extensive coverage of energy policy, drilling regulations, and the potential environmental challenges in relation to the oil spill, but most of this coverage was not included in this sample because most of the policy discussions did not mention seafood. As such, no link was established from energy policies and resource extraction to potential ecological impacts, to implications for the safety of the food supply. If a function of risk communication in the news media is to address risk on a short-term scale and avoid immediate hazards, an informational need remains to advise consumers as to what they should look for when purchasing fish. If mentioning risk in the news is to play a larger function of understanding cause so that various publics may pursue prevention efforts at the policy level, then reporting would need to better link the many steps that lead to the focused discussion of seafood safety.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, although our data are sourced from leading local and national newspapers, these were not randomly selected from a sample of all national and local newspapers, and we cannot make inferences about the presentation of seafood safety in all newspapers, nor are these findings necessarily directly generalizable to other types of news sources. Second, we limited our focus to news stories that included some mention of seafood, and therefore we are not able to comment on the relative frequency of discussing seafood safety versus other topics in oil spill coverage. Because we selected for discussion of seafood, we applied a specific filter to this coverage that most other media consumers likely did not; the trends we identified may not be salient to other readers. Similarly, alternative temporal groupings of articles might have yielded different findings. Finally, seafood safety was covered in many venues other than newspapers—television, radio, Internet blogs, magazines45—and we do not purport to cover the entire landscape of seafood safety discussions here.

Conclusions

The news media is not primarily in the business of health education nor is it the sole way people understand and experience risk.45 Nonetheless, newspapers serve as a top source from which the public learns about risks, particularly in heightened awareness situations such as the Deepwater Horizon spill.3,46 Amid a complex disaster, journalists were able to present many perceptions of risk and highlighted controversy without making a spectacle of seafood safety. Still, risk reporting can be improved if either short- or long-term public health considerations are important to news media. The public health and risk communication community can build on existing interactions with journalists and government spokespeople to share perspectives about how most appropriately and effectively to frame and convey food risk messages and what the ultimate function of these risk messages is meant to be.47 In this research, articles in the Associated Press accounted for one third of the sample, and likely widely influenced additional reporting around the country. Accordingly, newswires may be particularly useful targets for building capacity around public health and risk communication. Increasingly, online news aggregator services would also be worth explicit empirical consideration.

A public health approach to communicating about Gulf seafood risk or a related scenario would emphasize 4 elements, several of which draw from theories of risk communication:

Providing information about the risk, including its geographic or other extent, magnitude, and direct and indirect causes5,7,9;

Explaining how individuals can avoid risk (for example, how to identify problematic food and where to go for more information) and what is being done to address risk7;

Providing context including background information about the food—both the food’s risks and its benefits—and pointing out specific information for vulnerable populations,11,48 as well as the risks and benefits of not consuming the food49; and

Suggesting policy-level and structural prevention approaches to help turn attention to the larger factors that led to this particular food risk.

Most or all of this information may be unavailable immediately after a threat is identified and journalists may have insufficient time to engage critically with sources that have overly narrow risk messages. Responsible journalists and spokespeople can nonetheless aim, at minimum, to emphasize that these are the key questions that must be addressed in order to most effectively minimize risks and advance the public’s health.

Acknowledgments

This research is the result of a grant provided to Dr. Katherine Clegg Smith entitled, “News coverage of the BP Oil Spill: Is seafood contamination part of the story?” from the Center for a Livable Future in the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was not required for this study because human participants were not involved.

References

- 1.National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling. Deep Water: The Gulf Oil Spill and the Future of Offshore Drilling. Report to the President. January 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 2.A different kind of disaster story. Journalism.org. August 25, 2010. Available at: http://pewresearch.org/pubs/1707/media-coverage-analysis-gulf-oil-spill-disaster. Accessed August 25, 2010.

- 3.Tulloch J, Zinn J. Risk, health and the media. Health Risk Soc. 2011;13(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lupton D. ‘A grim health future’: food risks in the Sydney press. Health Risk Soc. 2004;6(2):187–200. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson PB. Ethics and Communication Risk. Sci Commun. 2012. October 1, 2012;34(5):618–641. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frewer L. The public and effective risk communication. Toxicol Lett. 2004;149(1-3):391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin I, Petersen DD. Risk Communication in Action: The Tools of Message Mapping. Cincinnati, OH: National Risk Management Research Laboratory Office of Research and Development, Environmental Protection Agency; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edelstein M. Crying over spilled milk; contamination, visibility and expectation in environmental stigma. In: Flynn J, Slovic P, Kunruether H, editors. Risk, Media and Stigma: Understanding PUblic Challenges to Modern Science and Technology. Sterling, VA: Earthscan Publications Ltd; 2001. pp. 41–68. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laestadius LI, Lagasse LP, Smith KC, Neff RA. Print news coverage of the 2010 Iowa egg recall: Addressing bad eggs and poor oversight. Food Policy. 2012;37:751–759. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solomon GM, Janssen S. Health effects of the Gulf oil spill. JAMA. 2010;304(10):1118–1119. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rotkin-Ellman M, Solomon G. FDA risk assessment of seafood contamination after the BP oil spill: Rotkin-Ellman and Solomon respond. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(2):a55–a56. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yender R, Michel J, Lord C. Managing Seafood Safety After an Oil Spill. Seattle, WA: Hazardous Materials Response Division, Office of Response and Restoration, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gohlke JM, Doke D, Tipre M, Leader M, Fitzgerald T. A review of seafood safety after the Deepwater Horizon blowout. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(8):1062–1069. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahaffey KR, Clickner RP, Jeffries RA. Adult women’s blood mercury concentrations vary regionally in the United States: association with patterns of fish consumption (NHANES 1999–2004) Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(1):47–53. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Why Buy Lousiana? Louisiana Leads the Way. Louisiana Seafood Promotion and Marketing Board; 2012. Available at: http://louisianaseafood.com/louisiana_leads_the_way. Accessed February 27, 2012.

- 16.Law RJ, Kelly C, Baker K, Jones J, McIntosh AD, Moffat CF. Toxic equivalency factors for PAH and their applicability in shellfish pollution monitoring studies. J Environ Monit. 2002;4(3):383–388. doi: 10.1039/b200633m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Marine Fisheries Service. Fisheries of the United States. Silver Spring, MD: National Marine Fisheries Service, Office of Science and Technology; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Love DC, Rodman S, Neff RA, Nachman KE. Veterinary drug residues in seafood inspected by the European Union, United States, Canada, and Japan from 2000 to 2009. Environ Sci Technol. 45(17):7232–7240. doi: 10.1021/es201608q. 2011/09/01 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ylitalo GM, Krahn MM, Dickhoff WW et al. Federal seafood safety response to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(50):20274–20279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108886109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rotkin-Ellman M, Wong KK, Solomon GM. Seafood contamination after the BP Gulf oil spill and risks to vulnerable populations: a critique of the FDA risk assessment. Environ Health Perspect. 2012-Feb 2012;120(2):157–161. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greiner A, Smith KC, Guallar E. Something fishy? News media presentation of complex health issues related to fish consumption guidelines. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(11):1786–1794. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010000923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neff RA, Chan IL, Smith KC. Yesterday’s dinner, tomorrow’s weather, today’s news? US newspaper coverage of food system contributions to climate change. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(7):1006–1014. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008003480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Previous reopenings. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2011. Available at: http://sero.nmfs.noaa.gov/PreviousReopenings.htm. Accessed February 27, 2012.

- 24.Shrout P, Fleiss J. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice. New York, NY: Prentice Hall; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deepwater Horizon/BP Oil Spill. size and percent coverage of fishing area closures due to BP Oil Spill. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2011. Available at: http://sero.nmfs.noaa.gov/ClosureSizeandPercentCoverage.htm. Accessed February 27, 2012.

- 27.Nolan B. State shuts down fishing east of Mississippi River; Jindal, federal officials losing patience with BP efforts to control oil. Times-Picayune. May 1, 2010 A1. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson B. Crisis in Gulf eating at seafood lovers, restaurants; eateries stress fish being served is safe Times-Picayune. May 2, 2010 A1. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skoloff B. Associated Press; May 6, 2010. US works to assure public Gulf seafood is safe. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkinson K. Seafood tests under way, Pas lab is testing seafood. Mobile Register. May 21, 2010 A1. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skoloff B. Associated Press; June 7, 2010. Trained noses to sniff out Gulf seafood for oil. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Canulette A. Festivals offer tasty (and safe) seafood. Times-Picayune. June 24, 2010 H1. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gulf seafood declared safe; fisherman not so sure. Associated Press; August 2, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrews C. Seafood testing goes on. Mobile Register. August 17, 2010 A1. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neergaard, Lauran Seafood ‘CSI': NOAA hunts for minute traces of oil. Mobile Register. August 17, 2010 A4. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dearen J, Bluestein G. Associated Press; July 10, 2010. NOAA: Gulf seafood tested so far is safe to eat. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burdeau C, Ray H. Associated Press; May 2, 2010. BP defends record; Obama in La. as oil spill grows. [Google Scholar]

- 38.BP image recovering from spill, still low. Mobile Register. August 19, 2010 A7. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Eight things to know about how the media covered the Gulf. Journalism.org. August 25, 2010. Available at: http://www.journalism.org/node/21828. Accessed February 27, 2012.

- 40. Statements by seafood industry leaders supporting NOAA's fishing regulations announced today in response to the BP oil spill. RestoreTheGulf.gov. May 2, 2010. Available at: http://www.restorethegulf.gov/release/2010/05/02/statements-seafood-industry-leaders-supporting-noaas-fishing-regulations-announce. Accessed February 27, 2012.

- 41. NOAA Expands Commercial and Recreational Fishing Closure in Oil-Affected Portion of Gulf of Mexico. RestoreTheGulf.gov. May 7, 2010. Available at: http://www.restorethegulf.gov/release/2010/05/07/noaa-expands-commercial-and-recreational-fishing-closure-oil-affected-portion-gul. Accessed February 27, 2012.

- 42.Administration launches dockside chats to promote Gulf seafood safety awareness. RestoreTheGulf.gov. August 25, 2010. Available at: http://www.restorethegulf.gov/release/2010/08/25/administration-launches-dockside-chats-promote-gulf-seafood-safety-awareness. Accessed March 23, 2012.

- 43.Holmes B. Communicating about emerging infectious disease: the importance of research. Health Risk Soc. 2008;10(4):349–360. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ungar S. Hot crises and media reassurance: a comparison of emerging diseases and Ebola Zaire. Br J Sociol. 1998;49(1):36–56. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilkinson I. Grasping the point of unfathomable complexity: the new media research and risk analysis. J Risk Res. 2010;13(1):19–28. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kasperson R, Renn O, Slovic P et al. The social amplification of risk: a conceptual framework. Risk Anal. 1988;8(2):177–187. [Google Scholar]

- 47.West BM, Sandman PM, Greenberg MR. The Reporter’s Environmental Handbook. 3rd ed. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwartz J, Bellinger D, Glass T. Expanding the scope of environmental risk assessment to better include differential vulnerability and susceptibility. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(suppl 1):S88–S93. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fischoff B, Brewer NT, Downs JS. Communicating Risks and Benefits: An Evidence-Based User’s Guide. Silver Spring, MD: US Food and Drug Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]