Abstract

Although “population health” is one of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Triple Aim goals, its relationship to accountable care organizations (ACOs) remains ill-defined and lacks clarity as to how the clinical delivery system intersects with the public health system.

Although defining population health as “panel” management seems to be the default definition, we called for a broader “community health” definition that could improve relationships between clinical delivery and public health systems and health outcomes for communities.

We discussed this broader definition and offered recommendations for linking ACOs with the public health system toward improving health for patients and their communities.

WITH THE PASSAGE OF THE Affordable Care Act (ACA),1 the United States has turned its attention to improving the quality of health care while simultaneously decreasing cost. As we move toward alternative and global payment arrangements, the need to understand the epidemiology of the patient population will become imperative. Keeping this population healthy will require enhancing our capacity to assess, monitor, and prioritize lifestyle risk factors that unduly impact individual patient health outcomes. This is especially true, given that only 10% of health outcomes are a result of the medical care system, whereas from 50% to 60% are because of health behaviors.2,3 To change health behaviors, it will be necessary to engage in activities that reach beyond the clinical setting and incorporate community and public health systems.4

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), a leading not-for-profit organization dedicated to using quality improvement strategies to achieve safe and effective health care, has developed the Triple Aim initiative5 as a rubric for health care transformation. The three linked goals of the Triple Aim include improving the experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing per capita costs of health care.6 However, although two of the three aims–experience of care and cost reduction–are self-explanatory, there is little consensus about how to define population health. Words like “panel management,” “population medicine,” and “population health” are being used interchangeably. Berwick et al.6 describe the care of a population of patients as the responsibility of the health care system and use broad-based community health indicators as evidence of improvement. Other recent publications have attempted to describe population health from the hospital,7–10 primary care,11 and community health center perspectives.12 The “clinical view” identifies the population as those “enrolled” in the care of a specific provider, provider or hospital system, insurer, or health care delivery network (i.e., panel population).7 Alternatively, from the public health perspective,8 population is defined by the geography of a community (i.e., community population) or the membership in a category of persons that share specific attributes (e.g., populations of elderly, minority population). In either case, the context of a community and the existing social determinants of health, ranging from poverty to housing, are known to have substantial impact on individual health outcomes. Thus, ensuring the health of a population is highly dependent on addressing these social determinants and requires collaborative relationships with community institutions outside the health care setting.13,14

Two key concepts that will greatly influence the definition and actualization of population health in the post-ACA era include the accountable care organization (ACO)15 and the patient-centered medical home (PCMH).16 The ACO represents an integrated strategy at the delivery system level to respond to payment reform.15 These integrated systems of care are poised to manage a population of patients under a global payment model. The PCMH is focused on transforming primary care to better deliver “patient-centered” care and to address the whole patient, including their health and social needs.17,18 Both models will need to identify, monitor, and manage their “population” of patients. However, their ability to extend their definition of population health to encompass the entire community will depend on resources, market share, and the strength and capacity of collaborating community and public health organizations. As integrated delivery systems are asked to do more than focus on their own patients, they will require additional resources. These may come from a realignment of existing programs (community benefits), a return on investment from effective preventive care, or collaborative relationships with existing community and public health organizations.

In this article, we discuss two major points regarding ACOs and their approach to population health. First, ACOs should be committed to serving the health of the people in the communities from which their population is drawn, and not just the population of patients enrolled in their care to achieve the population health goal. Second, to achieve this expanded definition of population health, ACOs will need to engage in collaborative efforts with community agencies and the public health system. We describe a “community” definition of population health to be used in lieu of the “panel” definition and then outline the resources needed and strategies for collaboration. Finally, we offer recommendations to assist ACOs in realizing their population health goal.

DEFINING POPULATION HEALTH

Population health connotes a high-level assessment of a group of people.9 This epidemiological framework is often in direct opposition to the manner in which the health care system has cared for patients in a fee-for-service model: one individual at a time. Currently, population health is being seen in two distinct ways: (1) from a public health perspective, populations are defined by geography of a community (e.g., city, county, regional, state, or national levels); and (2) from the perspective of the delivery system (individual providers, groups of providers, insurers, and health delivery systems), population health connotes a “panel” of patients served by the organization.

In the post-ACA world, as payment models shift from fee-for-service to global payment, ACOs will necessarily reorient from a disease focus to a wellness focus to improve quality and contain costs. Although they will have an ethical and contractual obligation for the patients for which they care, their engagement in the larger community may be highly dependent on which members of the community population actually end up being part of a particular ACO or PCMH panel. The larger the overlap between an ACO panel and the community population, the more the overall health of the community will contribute to the ACOs' ability to keep their patients healthy. Similarly, the larger the overlap between community population and ACO panel, the more ACO health outcomes will drive community health indicators. Table 1 displays how an ACO might address a variety of characteristics, depending on the chosen definition of population health (none, panel of patients in the delivery system, all members of a community).

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of Various Approaches to Population Health in Accountable Care Organizations

| Approach | Focus on Individual Patients in Primary Care Settings | Panel Population = Population Health | Communitya Population = Population Health |

| Medical home | May or may not have medical home | Medical home implemented | Medical home implemented |

| Care coordination | Focuses on coordination within primary care setting | Focuses on coordination within delivery system and potentially some community resources | Focuses on coordination within delivery system and all community resources |

| Clinical prevention services | Implement all clinical prevention services in primary care | Implement all clinical prevention services in primary care | Implement all clinical prevention services in primary care |

| Community prevention services | No implementation of community prevention services | Limited implementation of community prevention services | Full implementation of community prevention services |

| Health indicators monitored | Measures for provider settings, but no alignment with delivery or community or public health systems | Measures for patients in the delivery system, but no alignment with community or public health systems | Measures for delivery system include measures at the community population level |

| Needs assessment | No attention to community needs assessment—focus only on primary care settings | May have some joint needs assessment but focuses on decisions within the delivery system | Joint needs assessment related to community population outcomes and joint selection of target areas for action |

| Relationship to public health system | No relationship | Coordinating structure may exist with public health | Governance and coordinating structures in place with public health agencies to improve community population health |

| Relationship to community agencies | No relationship | Coordinating structure may exist with some agencies to promote health for patients in delivery system | Formal coordinating relationships with community agencies to share community population health goals |

| Use of community health workers | Use within primary care system with little link to community | Use to coordinate across delivery system and some community resources | Use in clinical and community settings to improve community population health for all individuals in the community. |

| Financing for population health initiatives | None within a fee-for-service system | Limited financing within fee-for-service system; community benefits supports limited activities with community; special grants and demonstrations but no dedicated source | Increased financing for public health entities through state or federal streams or Prevention Trusts; global fee systems for delivery systems commit 5% to community population health outcomes |

| Governance to promote population health | None in place in primary care setting | Limited governance structures in delivery system; might participate on community coalition or in informal partnerships | Formal governance structures in place with community and public health agency; delivery system has a designate senior lead for population health and dashboard measures on population health |

Community can also equal geographic area.

Resources

As provider organizations are asked to embrace the broader community definition of population health, resources will be needed to support this role. These resources include access to data, funding, and collaborative relationships.

Data.

With the emergence of the electronic medical records, ACOs should become more facile at viewing their population as a whole and identifying trends across their panel’s health (age, gender, race, chronic conditions). The data needed for this endeavor are largely collected at the visit level by registration and clinical staff. With adequate health information technology, systems can now examine issues such as risk for future disease, comorbidities, and quality metrics across a defined population. Using these data, the ACO can also determine the zip codes and communities where a majority of their patients reside and compare their health indicators to the community health indicators for the same geography.

Data on community health indicators (e.g., preventive services use, infectious disease rates, lead paint exposure, occupational health issues, cancer rates, births, and deaths from vital statistics) are more accessible than ever before. The National Prevention Strategy19 and the Healthy People 2020 goals for the nation20 include health indicators for population health at the community level. Much of community health information resides with state and county or city health departments, some of which have online interactive data tools that are available to the public (MassCHIP-Massachusetts21). New tools, such as the County Health Rankings22 and the Community Health Status Indicators,23 are publicly available and allow users to obtain county-level health data. In some jurisdictions, provider organizations are identifying ways to share de-identified data with community health leaders to jointly identify priority prevention strategies.24

Funding.

ACOs will also need to identify financial resources to achieve population health goals. The current fee-for-service structure does not support population health efforts, and although demonstration grants may help, they cannot sustain ongoing work. Today, nonprofit hospitals are required to provide some support for community programs through the recently revised community benefit in the ACA.25 Realigning hospital community benefit programs with population health efforts can help support the expanded role.

Simultaneously, ACOs need to assess which preventive strategies will yield the best return on investment (ROI) for their patients. Evidence-based services that demonstrate ROI and improved health outcomes can help in this endeavor. Nationally, two sets of evidenced-based prevention services have been identified: clinical preventive services, such as mammography, immunizations, and smoking cessation26; and community preventive services, such as fluoridation, lead testing, and community screening.27 Many of the clinical preventive measures are considered quality measures by major accrediting systems (e.g., Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set or the National Committee for Quality Assurance) and are also included in health coverage under the ACA. Assuming an ROI is realized, dollars saved can shift to support community and public health initiatives. Additionally, the federal public health trust fund provides a new revenue stream to support prevention strategies directly tied to health improvement and cost containment.28 This was recently replicated in Massachusetts with the passage of Chapter 224.29

Collaboration.

Many of these evidence-based prevention practices fall within the purview of community agencies and the public health system outside of ACO responsibility. For example, smoking bans promulgated by public health authorities have affected smoking rates and secondhand smoke exposure and have led to lower risk of hospitalization for cardiac and pulmonary conditions.30 Therefore, ACOs that strive to improve population health within geography will need to develop partnerships to support prevention activities while integrating complementary efforts into clinical settings. In particular, the ACO’s relationship with the local public health authority or authorities is essential. Although the public health authority is not the only organization with which an ACO will need to collaborate, it is the only agency that has legal authority and mandates to protect, promote, and assure the health for every individual in the community.31 Despite the logic of this partnership, integrating public health and the delivery system has proven difficult.32,33 Today, the ACA poses an unprecedented opportunity to refocus these efforts. While ACOs are contemplating the best strategies for population health improvement, public health authorities are also recognizing their changing roles34,35 and their need to effectively align with providers.36 As health insurance expands, public health clinical services are likely to decrease, and core functions including surveillance, regulation, and quality assurance will be more important than ever before. States such as Massachusetts, Minnesota, Washington, and Vermont have already evolved from delivering direct services to providing “wrap around” services (e.g., outreach, care coordination) and maintaining the core public health functions. Under global payment models, ACOs will depend on public health authorities to address regulatory and policy issues that have wide-reaching health impact.37

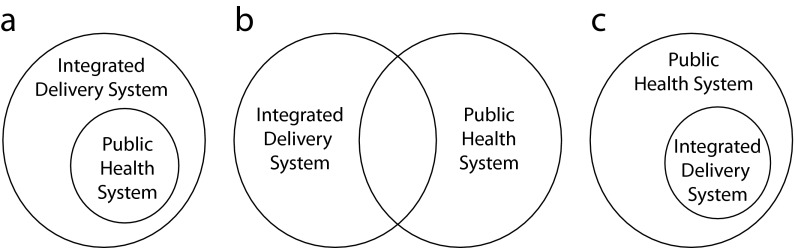

Figure 1 presents three possible relationships between health delivery and public health systems. When a community is served by one health system and one public health authority, integration efforts may be more easily achieved. However, in other cases, the delivery system will need to work with a number of public health authorities or the public health authority will need to work with numerous delivery systems.

FIGURE 1—

Relationships between integrated delivery system and public health system.

Strategies to Overcome Obstacles

To achieve alignment between provider organizations and community and public health agencies, strategies are needed to overcome multiple obstacles. For example, in highly competitive environments with multiple providers, a strategy of cooperation between clinical delivery systems and community and public health agencies is required to jointly improve population health. The Institute of Medicine report, Improving Health in the Community38 presented a method for multiple stakeholders in a community coming together to “share accountability” for population health outcomes. Weak public health infrastructure is another obstacle, and in these cases, the delivery system may need to shore up core public health functions (assurance, assessment, policy).31 In communities with strong public health systems, public health can address health from a policy and regulatory perspective while the health care system provides individual clinical prevention and treatment.37,39 ACOs may lack the appropriate skills and resources to achieve population health goals, posing another challenge. A strategy that identifies and connects an ACO to community and public health resources can enhance population health efforts. For example, many community and public health agencies have extensive experience and programs serving vulnerable populations and can assist ACOs in their outreach efforts. Overall, ACOs and public health systems can play complementary roles in improving population health goals as seen in the following examples.

An urban ACO serving a large city works with a local public health authority to identify geographic pockets of patients with diabetes. The ACO focuses on improved diabetes management in the clinical setting while linking to community resources for patients requesting exercise and physical activity options. Public health can lead a campaign to improve access to fresh fruits and vegetables and change policies related to menu labeling.

An ACO serving a number of suburban communities identifies high use of the emergency room from alcohol-related issues in young adults as a focus for improvement. Working with the public health authority, local schools, and substance abuse agencies, the collaboration creates a safe rides program and develops policies to monitor underage liquor sales.

An ACO serving a large rural population has trouble providing enough access for immunizations to elders. Community-wide access to immunizations is provided by working with the public health authority and local pharmacies. Communication strategies that link pharmacies and public health to the ACO are developed, along with an immunization registry for public health population-level surveillance.

Recommendations

It will take time for newly emerging ACOs to develop meaningful collaborative relationships with public health entities. We recommend the following steps for ACOs:

Determine in which geographic communities patients reside and what the overlap is between the ACO panel and the community population.

Compare the health of the population served by the ACO with that of the community.

Decide what level of overlap in any geographic area merits collaboration. The more market share an ACO has in the area, the more investment in collaboration might be made, and the more impact that investment will have on health outcomes.

Engage in collaboration with public health and key community agencies, including conducting a joint needs assessment.

Collaboratively select health outcomes for focus.

Set up a formal agreement with the public health authorities to share data and monitor progress toward goals in clinical and community settings.

Identify population health indicators to be included on the ACO dashboard.

Use a portion of global payment fee to support community public health activities.

CONCLUSIONS

To fully meet the goals of the Triple Aim, including improving the health of a population, ACOs must define “population health.” We recommend that they embrace the broad community definition of population health and take steps to work collaboratively with community and public health agencies. Future financing and value-based purchasing should reward collaborations that result in population health improvements at the community level. As health care moves toward alternative and global payment arrangements, the need to understand the epidemiology of the patient population is imperative. Keeping the population healthy will require enhancing capacity to assess and to monitor and prioritize lifestyle risk factors and social determinants of health that unduly affect health outcomes.

References

- 1.The White House A More Secure Future. What the new health law means for you and your family. Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/healthreform/healthcare-overview. Accessed June 18, 2012

- 2.McGinnis JM, Foege WH. Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270(18):2207–2212 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002;21(2):78–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker DK. Time to embrace public health approaches to national and global challenges. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(11):1934–1936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute for Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim Initiative. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/offerings/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed November 4, 2012.

- 6.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Health Research and Educational Trust, American Hospital Association Managing Population Health: The Role of the Hospital. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Association; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kindig D, Stoddart G. What is population health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(3):380–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis S. Creating incentives to improve population health. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(5)A93 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institute of Medicine Primary Care and Public Health: Promoting Integration to Improve Population Health. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cantor J, Cohen L, Mikkelsen L, Panares R, Srikantharajah J, Valdovinos E. Community-Centered Health Homes. Oakland, CA: Prevention Institute; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans RG, Stoddart GL. Producing health, consuming health care. Soc Sci Med. 1990;31(12):1347–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marmot M, Wilkinson RG. Social Determinants of Health. 2nd ed Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher ES, Shortell SM. Accountable care organizations: accountable for what, to whom, and how. JAMA. 2010;304(15):1715–1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barr MS. The patient-centered medical home: aligning payment to accelerate construction. Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67(4):492–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrews E, Toubman S. Patient-centered medical home: improving health care by shifting the focus to patients. Conn Med. 2009;73(8):479–480 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox JV, Kirschner N. Patient-centered medical home: renewing primary care. J Oncol Pract. 2008;4(6):285–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Prevention Council National Prevention Strategy. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Department of Health and Human Services Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Massachusetts Department of Public Health MassCHIP. Available at: http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/researcher/community-health/masschip. Accessed November 24, 2012

- 22.County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. Available at: http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/#app. Accessed November 4, 2012.

- 23.US Department of Health and Human Services Community health status indicators. Available at: http://wwwn.cdc.gov/CommunityHealth/homepage.aspx?j=1. Accessed November 25, 2012

- 24.Diamond CC, Mostashari F, Shirky C. Collecting and sharing data for population health: a new paradigm. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(2):454–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Internal Revenue Service Internal Revenue Bulletin: 2011-30. Notice 2011-52. Washington, DC: Internal Revenue Service; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 26.United States Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Washington, DC: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Department of Health and Human Services; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Task Force on Community Preventive Services Guide to Community Preventive Services: What Works to Promote Health? New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haberkorn J. Health Policy Brief: The Prevention and Public Health Fund. Health Affairs and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Bethesda, MD: Health Policy Briefs; 2012. Available at: http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=63. Accessed February 27, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Massachusetts Public Health Association Massachusetts Prevention and Wellness Trust Fund. Available at: http://www.mphaweb.org/documents/PrevandWellnessTrustFund-MPHAFactSheetupdatedOct12.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2012

- 30.Meyers DG, Neuberger JS, He J. Cardiovascular effect of bans on smoking in public places: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(14):1249–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Institute of Medicine The Future of Public Health. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brandt AM, Gardner M. Antagonism and accommodation: interpreting the relationship between public health and medicine in the United States during the 20th century. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(5):707–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stine NW, Chokshi DA. Opportunity in austerity–a common agenda for medicine and public health. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(5):395–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jarris PE, Leider JP, Resnick B, Sellers K, Young JL. Budgetary decision making during times of scarcity. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2012;18(4):390–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Young J, Resnick B, Leider JP. Perceived and anticipated impacts of the Affordable Care Act on state public health practice. Paper presented at the American Public Health Association Annual Conference; October 27–31, 2012; San Francisco, CA: Available at: https://apha.confex.com/apha/140am/webprogram/Paper260623.html. Accessed February 27, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benjamin GC.Transforming the public health system: What are we learning? Available at: http://iom.edu/Global/Perspectives/2012/TransformingPublicHealth.aspx. Accessed November 30, 2012.

- 37.Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(4):590–595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Institute of Medicine Improving Health in the Community: A Role for Performance Monitoring. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Institute of Medicine The Future of the Public’s Health in the 21st Century. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2003 [Google Scholar]