Abstract

Community resilience (CR)—ability to withstand and recover from a disaster—is a national policy expectation that challenges health departments to merge disaster preparedness and community health promotion and to build stronger partnerships with organizations outside government, yet guidance is limited.

A baseline survey documented community resilience–building barriers and facilitators for health department and community-based organization (CBO) staff. Questions focused on CBO engagement, government–CBO partnerships, and community education.

Most health department staff and CBO members devoted minimal time to community disaster preparedness though many serve populations that would benefit. Respondents observed limited CR activities to activate in a disaster. The findings highlighted opportunities for engaging communities in disaster preparedness and informed the development of a community action plan and toolkit.

THE NATIONAL POLICY enthusiasm for re-envisioning the preparedness agenda around community resilience (the ability to prevent, withstand, and mitigate the stress of a disaster) raises questions among local health departments (LHDs) about how to build or strengthen community resilience and how to integrate the “whole of community approach” (a community-integrated model to involve a diverse set of stakeholders) in usual disaster-planning activities.1–6 In the past 3 years, all federal agencies that oversee and fund state and local emergency preparedness and response developed requirements and some guidance to establish more of a focus on inclusion of communities in emergency planning and response activities, and as part of the Public Health Emergency Preparedness Cooperative Agreement, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now requires a set of capabilities in the area of community preparedness and resilience.2,4,7,8

The purpose of this focus is 2-fold. There is a recognition based on previous disaster experience domestically and internationally (e.g., Hurricane Katrina, Joplin tornado, Hurricane Sandy) that greater partnership between government and a diverse set of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs; both for-profit and nonprofit) is necessary for more effective response and recovery.9–12 Furthermore, there is new acknowledgment that the principles of community engagement used in other aspects of public health promotion, including those employed for daily stressors (e.g., community violence), may serve the best strategy for engaging historically vulnerable populations, leveraging existing community assets, and integrating routine and disaster activities.13 Moreover, the principles of community resilience (e.g., strengthening social connections, finding dual benefit opportunities between routine public health and disaster preparedness) address many of the social and environmental issues that aid communities to withstand and mitigate overlapping disasters.12,14,15

This new approach requires very different levels of partnership compared with the traditional top-down disaster response approach that has pervaded the past decade.3,5,9,16–18 Yet, even though all LHDs must address community resilience capabilities as part of their public health emergency preparedness cooperative agreement,7 key questions remain as to how LHDs can operationalize and measure this broader approach, and there are few examples of how to address these expectations. The Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience (LACCDR) Project is a comprehensive, community-based approach to answer these questions through both strategy and tactical activities, moving community resilience from conceptual (national policy and associated literature on community resilience) to operational (identifying and testing resilience-building activities in actual communities).

The structure of the partnerships, the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health (LACDPH) design strategy, and the community engagement approaches used are described elsewhere in this issue.6,13 This article summarizes findings from a baseline survey of governmental public health and community organizations to document initial capacities and practices regarding community resilience and describes the initial logic model for the LACCDR project. The LACCDR builds on a conceptual framework for community resilience that emphasizes the engagement, education, and interconnection of governmental and NGO partners considered essential to a community’s ability to mitigate vulnerabilities and recover from stress.5,12,19

DEFINING COMMUNITY RESILIENCE AND THE CONCEPTUAL MODEL

The LACCDR effort was guided by previous work in the area of community resilience conducted by several team members.5,20–22 This work included a literature review on community resilience in the context of public health or national health security and identified 5 core components of resilience for health security: (1) physical and psychological health of the population, (2) social and economic well-being of the community, (3) effective risk communication, (4) integration and involvement of organizations (both government and nongovernmental), and (5) social connectedness (more details on data abstraction are available5). This work also included a series of focus groups nationally with government and NGO stakeholders to solicit additional perspectives on community resilience.5 This research resulted in a definition in the context of public health emergency preparedness or national health security (any disaster with health impacts):

The ongoing and developing capacity of the community to account for its vulnerabilities and develop capabilities that aid in: preventing, withstanding, and mitigating the stress of an incident; recovering in a way that restores the community to self-sufficiency and at least the same level of health and social functioning as before the incident; and using knowledge from the response to strengthen the community's ability to withstand the next incident.23

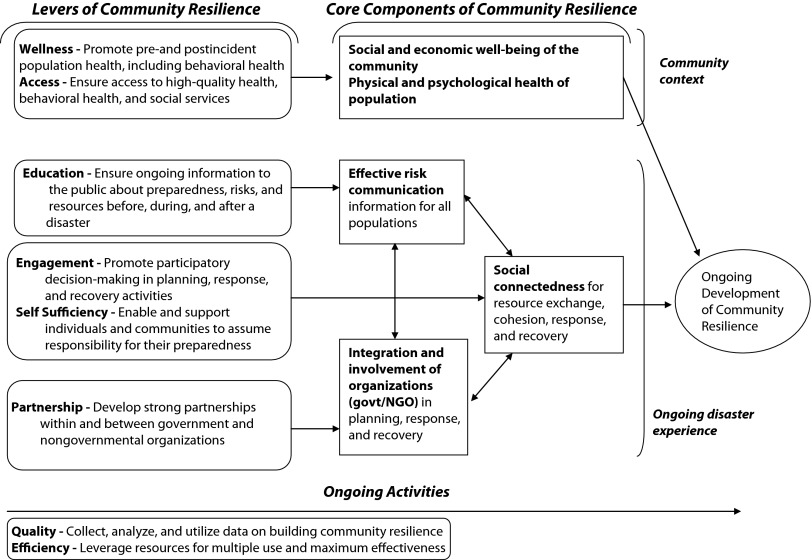

Figure 1 outlines the levers and core components of community resilience based on this literature review and stakeholder input.5 The core components are the main domains or factors associated with community resilience, such as the preexisting health of the population, derived from previous disaster research. It highlights that community resilience depends on the strength of social connections among community members and between community members and the community-based organizations (CBOs) that serve their needs. It also depends on the underlying health and well-being of the community. The capacity of residents to respond and recover from a disaster requires that they have access to timely information about the threat and appropriate response mechanisms. The levers are the means of addressing these core components, such as by improving a population’s access to health services.

FIGURE 1—

Core components and levers of community resilience, derived from disaster research.

Note. govt/NGO = government and nongovernment organization.

Source. Data from Chandra et al.5

Wellness relates to pre- and postincident population health, including behavioral health. Working to improve health is important because the overall resilience of a community can rest on the extent to which community members practice healthy lifestyles. Promoting wellness also involves taking steps to mitigate vulnerabilities either by planning for or reducing (predisaster) a community’s vulnerabilities (e.g., number of people who need transportation assistance) that, if ignored, can render emergency response and recovery difficult.24–26

Access relates to ensuring access to high-quality health, behavioral health, and social services because these services contribute to the development of the social and economic well-being of a community and the physical and psychological health of the population. Improving access ranges from making appropriate links to existing services to supplying new services where none exist. Specific to the disaster experience, education (ensure ongoing information to the public about preparedness, risks, and resources before, during, and after a disaster) can be used to improve effective risk communication. Community education means that individuals know where to turn for help both for themselves and their neighbors, enabling the entire community to be resilient in the face of a disaster.

Engagement (promote participatory decision-making in planning, response, and recovery activities) and self-sufficiency (enable and support individuals and communities to assume responsibility for their preparedness)18,27–29 are needed to build social connectedness particularly in neighbor-to-neighbor reliance, critical to resilience. Engagement also includes the general level of participation in preparedness and resilience building, particularly for at-risk or vulnerable populations, which are often poorly integrated into plans but face challenges in recovery and response. Self-sufficiency, or the active engagement of individual citizens in response, is important because individuals are often the first responders to incidents and must be effective in bystander reactions. Furthermore, we know that disaster conditions can prevent the deployment of external aid until the acute phase of the emergency has passed; thus, communities have to leverage existing resources.30–33

Partnership (develop strong partnerships within and between government and NGOs) helps ensure that government and NGOs are integrated and involved in resilience building and disaster planning, another essential feature of resilient communities.9,18,34 Quality, or a community’s ability to collect, analyze, and utilize data, is a critical lever needed to monitor and evaluate progress on building community resilience.35 Finally, developing sustainable processes and resilience-strengthening activities requires an integration of any new efforts within the foundation already established by existing organizations. Greater efficiency (leverage resources for multiple use and maximum effectiveness) is particularly needed in the processes involved in recovery from a health incident because significant human and financial costs can be incurred as a result of gaps in services or unnecessary redundancies.16,20,36,37 As denoted in Figure 1, both quality and efficiency are reflected throughout the entire resilience-building process.

The LACCDR program will eventually focus on all 8 levers; however, on the basis of discussions in stakeholder working groups on the most important immediate needs, we are principally focused on bolstering the 3 levers of partnership, engagement, and education at this stage. We also focused on these 3 levers because partnership and engagement of the community was cited as a critical goal for LACDPH, and education is essential to achieving broader community participation and enhancing resilience. Finally, these levers are considered mutable by stronger networks among government agencies and NGOs. As such, they are a means of achieving many of the other levers, such as greater community wellness or more efficiency in linking routine public health with disaster preparedness activities (efficiency).

The objective of the baseline survey was to measure the baseline activities related to these 3 levers in the community resilience framework, before the implementation of a 3-year capacity-building process, among the key stakeholders of this project—the LACDPH and members of the Emergency Network of Los Angeles (ENLA), an umbrella organization for CBOs, faith-based organizations, and private-sector organizations that serve in disaster response support roles but primarily provide routine services to address community needs. This network is the Los Angeles chapter of Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster.

METHODS

The baseline survey was administered via online platforms (Survey Select and LimeSurvey), preceded by an e-mail invitation describing the study. Our survey window was 3 weeks (between February and March 2011), and respondents were reminded 3 times via e-mail over that period to complete the survey. The goal was to complete the baseline survey before the first project kick-off meeting, so that we captured attitudes and activities before project exposure.

Sample Characteristics

We surveyed a sample of staff representing all divisions within LACDPH and community organization members of ENLA during February through March 2011, before the first LACCDR community meeting that marked the official start of the LACCDR project. We invited all ENLA member organizations (n = 86) to participate in the survey and a stratified sample of LACDPH employees (by DPH division) via online invitation (n = 190). We chose to use a stratified approach to the LACDPH survey because the number of staff is quite large in LACDPH (approximately n = 4000) and the stratification ensured that we received survey representation from across the divisions within the agency. This was critical because 1 aim of LACCDR is to bridge the disaster preparedness work in public health with other community health activities (e.g., maternal and child health). We selected staff from each of 23 programs in LACDPH. We randomly selected names among levels of staff in each program to ensure we included program directors or managers, service providers, and administrative staff. We also attempted to sample proportionately to the size of the program; thus, we had almost 40 to 50 names from each of the 3 largest programs (Emergency Preparedness and Response, Acute Communicable Disease, and Community Health Services).

Survey Content

The survey included 4 categories of questions—demographics on the individual or organization completing the survey including roles in disaster preparedness, response, and recovery (engagement); strength of partnerships between LACDPH and CBOs, and among CBOs for disaster response and recovery functions (partnerships); and current activities to educate community members about education and build resilience (education). In addition, we included questions about barriers to strengthening community resilience in Los Angeles County, and general resilience perspectives. We also queried LACDPH staff about whether their division focused on 1 or more of public health’s core services, and for ENLA, we queried about a range of organizational services and assets by using the International Classification of Nonprofit Organizations and the role of nonprofits in disasters.38 Because of the potential differential definition of disaster, we defined this term for respondents to be a range of natural and manmade disasters and defined community resilience as the ability to withstand, mitigate, and recover from disaster. This ensured consistency with national policy. Table 1 summarizes types of questions by lever.

TABLE 1—

Question Content by Community Resilience Lever (Engagement, Partnership, Education) Derived From Disaster Research

| “Lever” or Domain Area | Question Content |

| Engagement, including current level of preparedness activity | Activities that organization conducts in disaster preparedness, response, and recovery (preparedness: risk communication, volunteer operations, training and exercises, animal services, partnership development, staff training, environmental preparedness, community engagement; response: all and add staff mobilization; recovery: all and add response and recovery evaluation) |

| Engagement with “vulnerable” or at-risk populations, including modes and types of risk communication | |

| General time allocation to disaster preparedness, response, and recovery | |

| Partnership | Formal and informal relationship between LACDPH and various community-based organizations (neighborhood associations, faith-based organizations, businesses, other) |

| Formal and informal relationships between LACDPH and ENLA | |

| Education, including perspectives on resilience | Perception of individual or household and organizational readiness (preparedness education level) |

| Proposed and future activities to disseminate information about disaster preparedness and community resilience | |

| Perspectives on level of neighbor-to-neighbor reliance and volunteer capacity | |

| Perspectives on community-resilience capabilities, including recent event response (e.g., H1N1 influenza) and ability to educate community |

Note. ENLA = Emergency Network of Los Angeles; LACDPH = Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Source. Data from Chandra et al.5

We developed the survey items in concert with LACCDR steering committee members, representing LACDPH, ENLA, University of California Los Angeles, and RAND leadership. In most cases, items were newly constructed for the study because of the limited survey questions in the area of community resilience. However, we examined previous community resilience studies to identify response lists, such as core community resilience activities and capabilities (e.g., the ability of community organizations to educate their members about disaster or disaster preparedness; effective partnerships between government authorities and CBOs including businesses and schools). The study team also reviewed other disaster preparedness surveys to abstract relevant questions that could be used or modified for LACCDR; however, in most cases survey items did not exist for the concepts we planned to query in our instrument.39,40

We pilot tested the instrument with 10 respondents (5 LACDPH, 5 CBOs) to assess readability and flow as well as to determine if respondents interpreted the questions as we intended.

Analyses were purposefully descriptive at this stage because the goal of the baseline survey was to assess general community interest and challenges. In addition, the sample size and differences in how LACDPH (individual staff members nested in division within agency) and ENLA organizational representatives were sampled precluded robust comparison with weights at this time. However, we did disaggregate findings within LACDPH by representatives of the Emergency Preparedness and Response Program (EPRP) and all other divisions, where relevant.

RESULTS

We received 98 complete surveys and 6 partial surveys from LACDPH staff (out of 190, response rate = 55%) and 29 surveys and 2 partial surveys from ENLA (out of 86, response rate = 36%).

We queried LACDPH and ENLA respondents about their division or department or organization type, respectively. Respondents from LACDPH represented 23 programs within DPH. Approximately 30% (29 out of 98 surveys) of the LACDPH respondents were from the EPRP. The next largest groups were from the Acute Communicable Disease Program and Community Health Services. For ENLA, most respondents represented tax-exempt charitable organizations, foundations, or service organizations, and most worked in social services, followed by health or education.

Because ENLA represents a wide range of organizations with varying capacity, we queried respondents about their overall paid and volunteer staff size and their membership, particularly as this has implications for disaster resilience. Twenty-one organizations had individual members or constituents, though reported membership size varied from 1 to 120 000 (the median membership size was 40 and the mean membership size was 7383). Twenty of the organizations reported having between 1 and 15 000 volunteers (the median number of volunteers was 200 and the mean number of volunteers was 1278).

In addition to these basic demographic characteristics, we asked respondents to describe their usual array of activities. The LACDPH respondents were focused on a range of public health core services, particularly monitoring health status, developing public health policies, and engaging the community. Fifteen of the ENLA organizations considered public safety or disaster preparedness as a daily activity (48%), followed by 11 organizations focused on human services (35%), and 10 engaged in food and nutrition activities (32%). As this baseline survey also served as a needs assessment to inform the LACCDR project, these data illustrated where opportunities may exist to leverage community partnerships in other parts of LACDPH or with ENLA organizations (data not shown).

Activities and Engagement in Disaster Preparedness

We queried respondents about their current activities in disaster preparedness (on a scale of none [0% time]; a little [1%–24% time]; some [25%–49% time], most [50%–74% time]; nearly all [75%–99% time]; and all [100% time]). Approximately 63% of ENLA respondents noted that they only spent “a little time” devoted to disaster preparedness activities (< 25% time), which could include disaster planning, response, or recovery activities. Representatives of divisions outside EPRP noted a slightly different story, with 37% reporting “a little” participation in disaster preparedness and 31% reporting at least some effort devoted to preparedness (25%–49% time). Sixty-nine percent of EPRP staff indicated that they spent all or nearly all of their time (75% or more) devoted to disaster planning activities.

In addition, we queried ENLA organizations about their specific activities in disaster preparedness, response, and recovery activities (Table 1). This information provided insight into their general level of engagement, but also the extent to which they were involved in educating their staff and community residents about preparedness. Top responses for the preparedness phase included organizational preparedness (50%) and training and exercises (45%). The ENLA organizations were less involved in risk communication (26%), partnership development (35%), or environmental preparedness (23%). In the response phase, key ENLA activities were staff mobilization (45%) and organizational response (45%). Community engagement was more commonly cited in recovery (42%) rather than preparedness (35%) and response (29%).

As described earlier, engagement addresses participatory decision-making; therefore, a key step is to ensure that vulnerable or at-risk populations are included in disaster preparedness activities. The ENLA respondents tended to report more engagement of these populations than did LACDPH staff. There were some distinctions between ENLA, LACDPH–other divisions, and LACDPH–EPRP engagement of at-risk populations; only 47% of EPRP staff noted engagement of limited-English-proficiency populations compared with 56% of LACDPH–other divisions and 69% of ENLA respondents. Approximately 57% of EPRP staff noted engagement of low-income populations compared with 87% of LACDPH–other divisions and 75% of ENLA respondents.

Current Partnerships in Disaster Resilience

A critical aim of LACCDR is to strengthen partnerships where gaps exist, and to leverage current partnerships particularly between LACDPH and ENLA member organizations where opportunities exist to bolster community resilience. Formal partnerships were defined as having some type of agreement in place including a memorandum of understanding or membership on a coalition, where informal relationships were defined as occasional meetings or other correspondence.

We were most interested in the types of organizations with which LACDPH had partnerships (e.g., business, faith-based organizations) because these relationships could be accessed and potentially expanded through the ENLA network in LACCDR. All other divisions of LACDPH tended to have fewer formal relationships with neighborhood associations (8%) and businesses (9%) than with hospitals (34%) and health clinics (34%). We found similar trends for LACDPH–EPRP though the business relationships were more common (25% had formal relationships). Only 39% of ENLA organizations reported a formal partnership with LACDPH.

Education About and Perspectives on Resilience

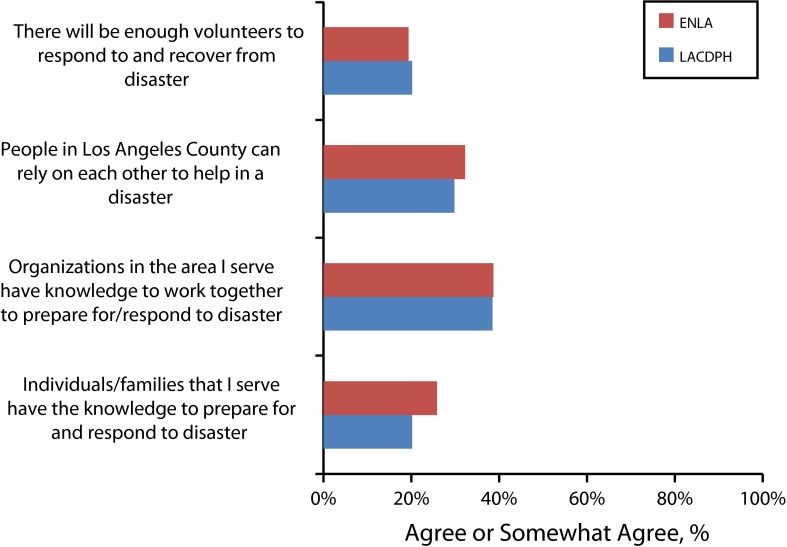

The third “lever” or arm of our analysis was to assess education activities provided by both ENLA and LACDPH. In addition, we were interested in exploring current perspectives on resilience (Figure 2). In general, relatively few respondents agreed (or somewhat agreed) with statements that individuals in their communities had necessary preparedness knowledge (28% ENLA, 20% LACDPH) and that people could rely on each other in disaster (32% ENLA, 30% LACDPH). However, somewhat more respondents believed that there was organizational readiness and knowledge to align resources to improve community resilience outcomes (39% ENLA, 37% LACDPH).

FIGURE 2—

Perspectives on current community resilience in Los Angeles County: survey of staff from Los Angeles Department of Public Health and Emergency Network of Los Angeles, 2011.

Note. ENLA = Emergency Network of Los Angeles; LACDPH = Los Angeles Department of Public Health.

Using H1N1 influenza as the recent disaster example, we queried respondents about their satisfaction that LACDPH currently exhibited core community resilience capabilities, including educating residents. Approximately 73% of LACDPH staff were satisfied with their ability to educate the public about H1N1 before it occurred (vs 60% of ENLA respondents), and nearly 80% felt satisfied in their ability to communicate information after the event had started (vs 58% of ENLA respondents). The LACDPH respondents were more satisfied with their ability to improve individual or family preparedness before H1N1 than were ENLA respondents (65% LACDPH were very or somewhat satisfied vs 19% of ENLA organizations). Approximately 42% of ENLA organizations reported satisfaction with LACDPH ability to connect with CBOs in preparedness compared with 55% of LACDPH staff. In addition, both LACDPH (42%) and ENLA (35%) respondents were the least satisfied in their ability to attend to special needs or traditionally vulnerable populations compared with other areas of H1N1 response.

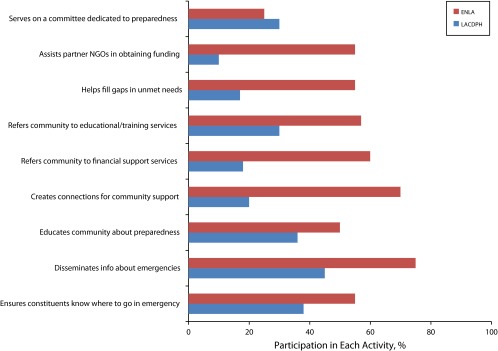

In addition to community resilience assessments, we asked respondents about current efforts or education to support community resilience (Figure 3). The ENLA organizations were more engaged in community resilience activities than LACDPH. About 36% of LACDPH staff had educated constituents about preparedness, whereas 50% of ENLA respondents had conducted that type of education. Approximately 55% of ENLA staff reported educating constituents about preparedness and 75% reported disseminating information (vs 38% and 45% of LACDPH staff, respectively). The ENLA organizations reported more activities in creating connections for social support, a key indicator of a community’s ability to rebound from disaster.12

FIGURE 3—

Current community resilience activities implemented by LACDPH and ENLA: survey of staff from Los Angeles Department of Public Health and Emergency Network of Los Angeles, 2011.

Note. ENLA = Emergency Network of Los Angeles; LACDPH = Los Angeles Department of Public Health.

In terms of barriers to implementing community resilience activities, ENLA reported a lack of materials in preparedness to share with community members (50%) and 25% noted a lack of preparedness training. Staff of LACDPH reported these barriers to resilience—lack of community interest in preparedness (40%) compared with ENLA respondents (25%), as well as lack of organizational interest in preparedness (25%) compared with ENLA (18%).

DISCUSSION

The analysis of the early development of the LACCDR provides an important and timely template for practitioners developing similar resilience-building strategies in response to new federal mandates. Moreover, guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on building more disaster-resilient communities is directed at all LHDs, but there are few examples of challenges, particularly the capacity of potential CBO partners. By tracking and documenting these efforts in Los Angeles, all LHDs that must address these goals will have some early insight into ways to embark on similar activities. Plus, this study provides potential community resilience indicators for the field to analyze as well as to provide a framework for measurement, which other jurisdictions might use.

The baseline survey of LACDPH and ENLA organizations provides an important first snapshot for how these staff members or organizations view community resilience, their baseline engagement in resilience-building activities and preparedness generally, and the extent of current partnerships between LACDPH and CBOs. These data provide the initial information for assessing gaps in engagement, partnership, and education in both ENLA and LACDPH and indicate the types of project activities that may be required to improve resilience outcomes.

There are several findings of note from this first survey. In the area of engagement, many LACDPH staff members, particularly those outside of the EPRP, did not devote significant time to disaster preparedness activities in the communities that they served, yet they engaged many of the vulnerable populations in other public health promotion activities that also require this type of information. In addition, despite the fact that current ENLA members tend to be more “disaster-ready” because of their engagement within the Los Angeles chapter of Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster, many of these organizations still only spend “a little” time in preparedness. Furthermore, although ENLA members focused time on organizational readiness, they noted less activity in partnership development and community engagement, which could be an asset provided by ENLA organizations in strengthening resilience. The challenge for LACCDR is to build institutional and community capabilities in these areas before the response phase.

In the area of partnership, the survey responses are also informative. First, LACDPH and ENLA do not have many formal connections between these 2 organizations for disaster response and recovery. Second, LACDPH also has not fully leveraged community partnerships that may be critical for disaster resilience yet, principally those relationships with nontraditional organizations that have community reach, such as neighborhood associations, faith-based organizations, and businesses. In addition, the limited participation of ENLA members on preparedness committees (only 25% reporting membership) could also change. For LACDPH, there may be opportunities to work with ENLA to engage constituents in preparedness, particularly because LACDPH staff tended to report less community interest in these topics than did ENLA respondents.

Finally, perhaps the most critical findings were in the domain of education, including activities to disseminate preparedness information and general perspectives on community resilience. Although community resilience rests on the strength of individual and neighborhood-level preparedness,1,4,5,12,18 the assessment of household preparedness and neighbor-to-neighbor reliance in a disaster was low. The majority of LACDPH and ENLA respondents did not think that individuals or households in Los Angeles County had the knowledge necessary to prepare and respond effectively, even though most of the ENLA respondents noted that they spent time educating their members about disaster preparedness. As ENLA organizations are already developing social networks for support as evidenced by their current community resilience activities (Figure 3), these organizations may need to be leveraged more consistently for broader neighborhood and community-preparedness education. Furthermore, although LACDPH was very satisfied with its ability to educate the public about H1N1 before and during the event, most staff members still identified a need to improve both individual and organizational preparedness.

Limitations

There are study limitations that should be noted. First, the study was conducted in a large county and as such is most directly relevant to other large metropolitan LHDs (which do serve about 60% of the US population). However, many of the principles addressed in the study (e.g., enhancing neighborhood support, partnership between government agencies and NGOs) are critical to any community’s efforts to strengthen public health and build disaster resilience. Plus, the Los Angeles County area contains urban, rural, and suburban populations representing diverse populations.

In addition, low survey return rate from ENLA organizations is a concern, though we obtained a diversity of organizations in the small sample including public safety, health, education, human services, and nutrition that comprise the majority of the ENLA population. The low response rate may be indicative of a lack of engagement or lack of clarity about the study’s purpose; both issues should be addressed by LACCDR. As such, we may be obtaining perspectives from ENLA members that are more engaged in preparedness, perhaps underestimating some of the challenges or barriers. Also, our survey was focused on partnerships between ENLA and LACDPH; we did not query ENLA about relationships with other government agencies. In addition, as described earlier, the sample design for this survey purposefully allowed for descriptive analyses only. We were unable to include subanalyses of differences by ENLA organization or LACDPH program type because of differential sampling strategy and sample size within groups. Future evaluation will include more robust measurement of change over time in pilot neighborhoods as well as comparison between LACDPH divisions and between LACDPH and ENLA.

Finally, the lack of tested measures in community resilience is a limitation. However, one objective of this study was to further test and validate items, such as those included in this baseline survey, which could inform a community-resilience index and current national efforts to create a health security preparedness index.

Conclusions

With the baseline findings and a study logic model,41 the LACCDR team has completed a rigorous workgroup process,30 which guided the development of the community resilience action plan, principally through a community resilience toolkit. The community resilience toolkit includes a set of strategies and materials that planning groups will use over the next 3 years to build resilience in their communities including components that were deemed high priority areas in the survey such as partnership development and social preparedness. Findings from this survey and the larger demonstration evaluation13 will significantly advance the fields of public health and disaster preparedness simultaneously, surfacing key strategies that will build community resilience, and assessing whether and how indicators of partnership, education, and engagement can be improved to enhance that resilience. This baseline assessment represents an important first step toward understanding community resilience challenges and opportunities in a large county and illustrates specifically how government and NGOs can strengthen ties and leverage a greater diversity of assets to more effectively respond to disasters or other emergencies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant 2U90TP917012-11).

The authors wish to thank survey participants and Brittney Weissman and Benjamin Bristow for their commitment to the project.

Note. The findings are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funders.

Human Participant Protection

The study was reviewed by the RAND Human Subjects Protection Committee and deemed exempt.

References

- 1.Allen KM. Community-based disaster preparedness and climate adaptation: local capacity-building in the Philippines. Disasters. 2006;30(1):81–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.2006.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency. National disaster recovery framework: strengthening disaster recovery for the nation. Available at: http://www.fema.gov/pdf/recoveryframework/ndrf.pdf. AccessedMay 20, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency. A whole community approach to emergency management principles, themes, and pathways for action. Available at: http://www.fema.gov/library/viewRecord.do?id=49412011. AccessedMay 20, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Department of Homeland Security, Federal Emergency Management Agency. National health security strategy of the United States of America. Available at: http://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/authority/nhss/strategy/Documents/nhss-final.pdf. AccessedJanuary 26, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandra A, Acosta J, Stern S . Building Community Resilience to Disasters: A Way Forward to Enhance National Health Security. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2011. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plough A, Fielding J, Chandra A et al. Building community disaster resilience: perspectives from a large urban County Department of Public Health. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(7):1190–1197. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Public Health Emergency Preparedness Capabilities. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Homeland Security Presidential Directive/HSPD-21: Public Health and Medical Preparedness. Washington, DC: US Department of Homeland Security; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alesi P. Building enterprise-wide resilience by integrating business continuity capability into day-to-day business culture and technology. J Bus Contin Emer Plan. 2008;2(2):214–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keim M. Using a community-based approach for prevention and mitigation of national health emergencies. Pac Health Dialog. 2002;9(1):93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Acosta J, Chandra A. Harnessing community for sustainable disaster response and recovery: an operational model for integrating nongovernmental organizations. Disaster Manag Public Health Prep. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2012.1. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore M, Chandra A, Feeney K. Building community resilience: What the United States can learn from experiences in other countries? Disaster Med Public Health Prep. Epub ahead of print. April 30, 2012 doi: 10.1001/dmp.2012.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wells K, Lizaola E, Tang J et al. Applying community engagement to disaster planning: developing the vision and design for the Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience (LACCDR) initiative. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(7):1172–1180. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yong-Chan K, Jinae K. Communication, neighbourhood belonging and household hurricane preparedness. Disasters. 2010;34(2):470–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2009.01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyn K, Martin JA. Enhancing citizen participation: panel designs, perspectives and policy formation. J Policy Anal Manage. 1991;10(1):46–63. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandra A, Acosta J. The Role of Nongovernmental Organizations in Long-Term Human Recovery After Disaster: Reflections From Louisiana Four Years After Hurricane Katrina. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2009. OP-277-RC. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schoch-Spana M, Franco C, Nuzzo J, Usenza C. Community engagement: leadership tool for catastrophic health events. Biosecur Bioterror. 2007;5(1):8–25. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2006.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norris FH, Stevens S, Pfefferbaum B, Wyche K, Pfefferbaum R. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(1-2):127–150. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baezconde-Garbanati L, Unger J, Portugal C, Delgado JL, Falcon A, Gaitan M. The politics of risk in the Philippines: comparing state and NGO perceptions of disaster management. Disasters. 2006;33(4):686–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2009.01104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chandra A, Acosta J, Meredith LS . Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2010. Understanding community resilience in the context of national health security: a literature review. RAND working paper. Available at: http://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WR737. Accessed March 17, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandra A, Acosta J. Disaster recovery also involves human recovery. JAMA. 2010;304(14):1608–1609. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Acosta J, Chandra A, Sleeper S . The Nongovernmental Sector in Disaster Resilience: Conference Recommendations for a Policy Agenda. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandra A, Acosta J, Stern S . Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2011. Building community resilience to disasters: a roadmap to guide local planning. RAND research brief 9574. Available at: http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9574. Accessed March 17, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore S, Daniel M, Linnan L, Campbell M, Benedict S, Meier A. After Hurricane Floyd passed: investigating the social determinants of disaster preparedness and recovery. Fam Community Health. 2004;27(3):204–217. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200407000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andrulis DP, Siddiqqui NJ, Gantner JL. Preparing racially and ethnically diverse communities for public health emergencies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(5):1269–1279. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aldrich N, Benson WF. Disaster preparedness and the chronic disease needs of vulnerable older adults. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(1):A27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGee S, Bott C, Gupta V, Jones K, Karr A. Public Role and Engagement in Counterterrorism Efforts: Implications of Israeli Practices for the US. Arlington, VA: Homeland Security Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magsino SL. Applications of Social Network Analysis for Building Community Disaster Resilience. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Putnam RD. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hearing, Post Katrina: What It Takes to Cut the Bureaucracy. Washington, DC: Subcommittee on Economic Development; 2009. Public Buildings, and Emergency Management. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacob B, Mawson A, Payton M, Guignard JC. Disaster mythology and fact: Hurricane Katrina and social attachment. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(5):555–566. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.AufderHeide E. Common misconceptions about disasters: panic, the “disaster syndrome,” and looting. In: O’Leary M, editor. The First 72 Hours: A Community Approach to Disaster Preparedness. Lincoln, NE: iUniverse Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helsloot I, Ruitenberg A. Citizen response to disasters: a survey of literature and some practical implications. J Contingencies Crisis Manage. 2004;12(3):98–111. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gajewski S, Bell H, Lein L, Angel RJ. Complexity and instability: the response of nongovernmental organizations to the recovery of Hurricane Katrina survivors in a host community. Nonprofit Volunt Sector Q. 2011;40(2):389–403. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brownson RC, Fielding JE, Maylahn CM. Evidence-based public health: a fundamental concept for public health practice. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:175–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paton D, Gregg CE, Houghton BF et al. The impact of the 2004 tsunami on coastal Thai communities: assessing adaptive capacity. Disasters. 2008;32(1):106–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2007.01029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pant AT, Kirsch TD, Subbarao IR, Hsieh YH, Vu A. Faith-based organizations and sustainable sheltering operations in Mississippi after Hurricane Katrina: implications for informal network utilization. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2008;23(1):48–54. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00005550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salamon LM, Anheier HK. The International Classification of Nonprofit Organizations: ICNPO—Revision 1, 1996. Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins Institute for Policy Studies; 1996. Working Papers of the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project, no.19. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bankoff G, Hilhorst D. The politics of risk in the Philippines: comparing state and NGO perceptions of disaster management. Disasters. 2009;33(4):686–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2009.01104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Citizen Corps. Personal preparedness in America: findings from the Citizen Corps National Survey. 2009. 2012 Available at: http://citizencorps.gov/resources/research/2009survey.shtm. Accessed May 21. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience Project. March 17, 2013 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301270. Available at: http://www.laresilience.org. Accessed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]