Abstract

Community resilience (CR) is a priority for preparedness, but few models exist. A steering council used community-partnered participatory research to support workgroups in developing CR action plans and hosted forums for input to design a pilot demonstration of implementing CR versus enhanced individual preparedness toolkits. Qualitative data describe how stakeholders viewed CR, how toolkits were developed, and demonstration design evolution.

Stakeholders viewed community engagement as facilitating partnerships to implement CR programs when appropriately supported by policy and CR resources. Community engagement exercises clarified motivations and informed action plans (e.g., including vulnerable populations). Community input identified barriers (e.g., trust in government) and CR-building strategies. A CR toolkit and demonstration comparing its implementation with individual preparedness were codeveloped.

Community-partnered participatory research was a useful framework to plan a CR initiative through knowledge exchange.

“We want information about how to identify resilience-building tasks and activities that communities can replicate. How can vulnerable communities fit into these activities to make sure they are also more resilient to disasters?”

–Workgroup member

Disasters such as wildfires, tropical storms, hurricanes, earthquakes, and epidemics pose temporary and long-term threats to public health.1,2 Underresourced communities are at high risk for adverse outcomes owing to preexisting disparities in health, access to services, and environmental risks.3–5 Large-scale events disrupt physical, social, and communication infrastructures posing challenges to response, and creating “surge burdens” that overwhelm care resources and strain social supports.6 Events such as Hurricane Katrina, the H1N1 epidemic, and the Gulf oil spill have increased public awareness of the impacts of disasters and of gaps in communication, infrastructure, and resources that limit capacities to respond and recover.3,7,8

One paradigm that has emerged in response is community resilience (CR).9,10 Based on a community-systems model,11,12 CR refers to community capabilities that buffer it from or support effective responses to disasters.13,14 Such capabilities include effective risk communications, organizational partnerships and networks, and community engagement to improve, prepare for, and respond to disasters. These capabilities may improve outcomes such as access to response and recovery resources, or return to functioning and well-being.15 Yet there are no operational models of how to build CR.16,17

One potential model is community-partnered participatory research (CPPR), a manualized form of community-based participatory research18 that emphasizes power sharing and 2-way knowledge exchange following principles of community engagement to support authentic partnerships.19–21 We define a community as persons who work, share recreation, or live in a given area. A CPPR initiative has 3 stages: vision (planning), valley (implementation), and victory (products, dissemination).22–24 Each stage involves organizing, action, and feedback.20 Community-partnered participatory research was used to support post-Katrina mental health recovery in New Orleans24–28 and to address chronic conditions.29–33 Following successful application of CPPR in a postdisaster context, we proposed that it could support development of predisaster CR programs. We describe here the use of CPPR for the planning or vision stage of the Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience (LACCDR) initiative.

As described elsewhere, LACCDR was initiated in 2010 by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health (LACDPH) in collaboration with key academic and community partners based on principles from the National Health Security Strategy.10 Representatives of these partners constitute the LACCDR Steering Council. The Council reviewed the policy background for CR34 and developed a logic model35 that emphasizes the importance of community engagement in developing organizational partnerships to build CR. This article focuses on how the Council then used community engagement principles and the CPPR model to develop the project’s CR intervention framework, propose and develop a toolkit containing training and other resources to improve CR, and design a demonstration to compare the effectiveness of implementing the CR toolkit with the enhanced standard approach that emphasizes individual or family preparedness.15,36

METHODS

The Council convened a Community Kick-Off Conference in March 2011, attended by more than 50 representatives of LACDPH; the Emergency Network of Los Angeles (ENLA), which is the Los Angeles County’s Voluntary Organizations Active in Disasters; emergency response agencies; local government and community-based organizations (CBOs); and unaffiliated community members to introduce the initiative and obtain feedback from stakeholders.34,35 Breakout groups discussed 3 questions: (1) What is your organization doing now to build community disaster resilience? (2) What challenges do you see in increasing community disaster resilience? (3) What would make your community more resilient? The feedback was synthesized by the Steering Council into recommendations for workgroups in 3 areas: (1) information and communication (IC), (2) partnerships and social preparedness (PSP), and (3) vulnerable populations (VP). Council members volunteered to co-lead workgroups, each of which included a broad range of government agencies and CBOs, unaffiliated community members, and academic partners. From May to December 2011, each group met biweekly to develop recommendations for CR interventions.

Leadership differed across groups: IC was led by 2 community members, VP by 2 academic members, and PSP by 2 academic and 2 community members. The workgroups used strategies to encourage participation, including votes on issues and rotating responsibilities for presentations. In the PSP workgroup community and academic cochairs jointly set the agenda, defined community engagement goals,20 and reviewed feedback based on postmeeting reflection sheets. Examples of the initial concerns raised by the group included unfamiliarity with emergency preparedness topics and a lack of transparency over which officials and organizations were responsible for emergency preparedness. Leadership responses included providing contact lists, readings, presentations by experts in emergency response, and developing a glossary of terms and resource guide. Workgroup leaders shared progress in weekly Council meetings.

The Council hosted a Community Response Conference in October 2011 with more than 40 attendees from CBOs and unaffiliated community members, featuring an overview of LACCDR goals, a summary of findings from a baseline agency survey,35 presentations by workgroups, and breakout open discussions. Attendees participated in a group exercise designed to demonstrate that collaboration is essential to building CR. In breakout discussions, there was broad support for proposed action plans but additional ideas were also developed and incorporated. For example, participants noted the importance of financial support for agencies to implement CR, a suggestion that later led to a CR-focused “minigrants” program. Participants also noted the importance of LACDPH staff buy-in, leading to a LACDPH Conference in January 2012, attended by more than 70 LACDPH staff. The discussions at the LACDPH conference focused on how CR programs might be developed, the challenges of shifting from traditional bioterrorism and top-down planning models toward community engagement, and the resources and staff training that would be required for successful implementation. Feedback included suggestions for outreach to vulnerable populations such as seniors and persons living with a disability.

Community Resilience Toolkit

The Council met in January 2012 to review and prioritize action plans and consolidate recommendations for training resources and technical assistance into a CR toolkit that could be implemented by neighborhood coalitions with LACDPH staff support and Council guidance. The Council implemented the minigrant program to support community input into toolkit components and develop engagement strategies. Using the information obtained across workgroups, broader community meetings, and agency surveys, the Council developed a design for a randomized pilot demonstration across 16 community coalitions to compare implementation of a CR toolkit with an enhanced standard preparedness approach focused on individuals and families. In preparation for the demonstration, supported by an evaluation subcommittee, restructured workgroups intensively developed specific toolkit components. The VP workgroup developed plans for engaging vulnerable groups and mapping assets and hazards within specific demonstration communities, with input from community participants who themselves were members of at-risk groups or were staff from organizations serving such groups. The combined IC and PSP workgroups developed an approach for responder agencies and other community leaders to collaborate in implementing a toolkit at the neighborhood level following principles of community engagement, including resources for community leaders developed under the minigrant program, and explored and selected approaches to train community health workers for CR. Between January and June 2012 the workgroups narrowed options for the toolkit and refined the demonstration design. In June 2012 the Council hosted a workshop attended by 35 workgroup participants including many community members to review the proposed demonstration plan.

Data Sources and Analyses

We used meeting minutes, field notes, and reflection sheets from workgroup and Council meetings to develop a framework for building CR capabilities, identify recommendations for the toolkit, and describe the proposed demonstration, clarifying community input and reactions. Qualitative data from conference breakout discussions were systematically analyzed for themes by using a grounded theory approach. Themes were assigned a code and 2 staff members and 2 Council members coded quotations independently. The κ scores ranged from 95% to 98% across 3 questions (SE ranged from 0.17 to 0.34), for excellent reliability. Two project staff and a Council member reviewed notes to develop consensus on descriptions, supplemented by workgroup cochair descriptions of activities.

Quotes and paraphrased excerpts were used to illustrate themes and to prepare a brief report that allowed for community participants to obtain immediate feedback on the project. A common community concern is that academics enter their community and take data without giving information back. Throughout the vision stage, reports and presentations were provided to community participants to illustrate how their input shaped the project and to provide updates on progress.

RESULTS

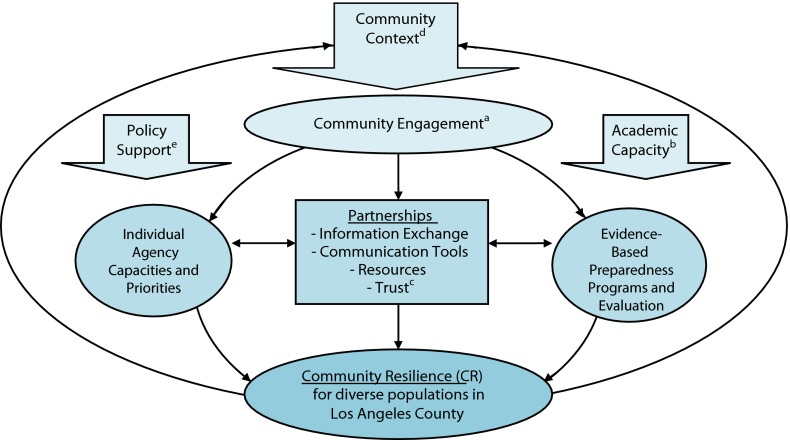

At the Kick-Off Conference, participants noted that their agencies provided education (36%) and outreach (21%), but few described building 2-way capacity in communities (10%): “We do training and planning to discuss emergency preparedness. [We] do exercises or drills to practice our strategies.” Challenges to addressing CR included time for engaging the community and lack of funding, policy support, or community resources: “In many communities they are already facing their rainy day. Preparing for tomorrow is a luxury they can’t afford.” Engagement was cited as a central strategy for making communities more resilient and was a higher priority than funding for preparedness activities. The framework (Figure 1) developed from the discussions highlights the importance of community engagement to enable partnerships that use communication and preparedness resources to build CR. It further clarifies that policy support is necessary for agencies to prioritize CR and have resources to engage communities, and that academic support facilitates access to evidence-based strategies and evaluation capacity. Examples of quotes that informed the framework are given in footnotes.

FIGURE 1—

Framework to build community resilience in Los Angeles County: Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience Initiative, August 2011.

aMarch 2011 (Kick-Off Conference): “[Community] engagement, getting buy-in… are challenges in increasing community resilience.”

bJune–August 2011 (Partnerships and Social Preparedness [PSP] Workgroup Discussions): “I would like to see practical applications of community engagement and community resilience.”

“We need more proactive inclusion of recovery needs in preparedness planning, especially psychological.”

cJune 2011 (PSP Workgroup Discussions): “Businesses are an important resource in communities that need to be included in partnerships.”

dJune 2011 (PSP Workgroup Discussion): “A revised framework can show how the community context informs community engagement and how community disaster resilience reshapes the community.”

eJuly 2011 (Weekly Council Meeting): “Policy support includes policy engagement and funding for agencies to increase their ability to pursue CR efforts.”

Recommendations for Community Resilience Toolkit

Recommendations for toolkits were developed from visioning exercises in which workgroup members identified goals or “wins” for themselves, their agencies, and their community (Table 1). Participants noted that it was difficult to separate individual, agency, and community goals as preparedness was a universal concern. Recommendations for the toolkit reflected members’ interests and experience. For example, Council members sought knowledge about CR and linkages to health promotion; PSP participants wanted to gain community engagement skills and develop a culturally relevant CR toolkit; VP members sought approaches to working with vulnerable groups, activate networks for CR, and sustain commitment to vulnerable groups. Table 1 illustrates themes.

TABLE 1—

Responses From Visioning Exercises: Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience Initiative

| Responses | PSPa | VPb | SCc |

| Individual gains | |||

| “Learn how public health nursing can become an asset in community engagement.” | X | ||

| “Inclusion of psychological recovery factors in preparedness planning.” | X | ||

| “Focus attention on vulnerable populations to make LACDPH work better with communities and vice versa.” | X | ||

| Defining different types of vulnerable populations with which to work | X | ||

| “This project presents a unique opportunity to do work that bridges public health policy and academic research. It would be really great to see community resilience incorporated into policy.” | X | ||

| Experience working with, learning from, and contributing to a great team | X | ||

| Contribute to working on social justice issues | X | ||

| “I would like to see the group be able to focus on the task in front of them. Come up with a direction and goal for the project. Once the direction and goal are set I would like to have a way to measure progress and outcome.” | X | X | |

| “Application of community engagement principles to community disaster resilience.” | X | X | X |

| Agency gains | |||

| “Learn how LACDPH can become a more acceptable, plausible partner through the community engaging processes.” | X | ||

| Clearer understanding of expected roles and responsibilities of government and community sectors after a disaster | X | ||

| Increase agency staff capacity—“We want to enhance the knowledge of promotoras to be able to send messages to the community.” | X | ||

| Greater appreciation of community needs and wants—trust from the community | X | ||

| Incorporation of community engagement into practice | X | ||

| Define and measure resilience to track progress—“We want information about how to identify resilience-building tasks and activities that communities can replicate. How can vulnerable communities fit into these activities to make sure they are also more resilient to disasters?” | X | X | |

| A culturally relevant community engagement toolkit—“The goal of my agency, or I should say me as the agency rep, would like to see a finished project that can be used as a model for all socioeconomic classes. As an emergency manager for a mid-sized city I believe it is important to be able to reach out and educate the citizens on the availabilities in their community in the event of a disaster. It would be nice to be able to use the same set of ‘educational tools’ on everyone.” | X | X | X |

| Access to knowledge, skills, and tools | |||

| A resource and referral directory | X | X | X |

| Development of operational guidelines or a strategic plan for agencies | X | X | X |

| Effective partnerships and network development—“For example, CERT Neighborhood Team Program needs to find concentrations of community residents that want to be trained and learn how to organize and function as a local team. Other groups with established constituencies can assist by communicating our need through their organization.” | X | X | X |

| Community gains | |||

| Relevance and involvement of the community: “I believe they would like to feel included in our mission. By asking for input from them we can achieve buy in.” | X | X | X |

| “Perhaps also, having some tools and methods relevant to disaster that become available for daily use for broader purposes, such as improving partnership strengths and capacities, coping with stress, or better outreach to vulnerable group.” | X | X | X |

| Addressing the needs of a community before a disaster through the recovery period | X | X | X |

| Clear, consistent messaging on disaster preparedness and ways to increase resilience | X | X | X |

| Preparedness and empowerment for underserved communities | X | X | X |

Note. CERT = community emergency response teams; LACDPH = Los Angeles County Department of Public Health; PSP = partnerships and social preparedness workgroup; SC = Steering Council; VP = vulnerable populations workgroup.

PSP workgroup convened June 2011.

VP workgroup convened July 2011.

SC convened January 2012.

In addition, the PSP workgroup engaged community members, with the help of ENLA leaders, in an exercise to prioritize CR capacities outlined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.37 The group’s highest ratings were for promoting the ability of communities to survive postdisaster without government assistance, developing partnerships between government agencies and CBOs, and building trust among community members. Members of the VP group’s priorities included identifying community assets to foster CR, including geographic information systems mapping to track vulnerabilities and assets, promotoras to build CR locally, and opportunities for faith-based and other organizations to build CR while sharing their daily work.

The Council integrated and prioritized workgroup recommendations by using a visioning exercise. Priorities included (1) tools to support responder community engagement skills and community members’ preparedness knowledge; (2) a free Web-based mapping tool to provide information on assets for building CR and to identify resources and potential areas of vulnerability or gaps in planning; (3) tools to help communities identify and develop CR leaders, including responders and other community members, and resources for health workers to support CR; and (4) a training module for psychological first aid (PFA), an approach to promote safety, social stability, and referral to achieve social and psychological resiliency.38–40 Participants across workgroups noted that PFA offered a “daily win” from a community perspective.

The box on the next page describes the proposed CR toolkits as well as components identified for enhanced “standard” public health practice for individual and family preparedness. The CR toolkit supports effective team leadership in training communities to use CR strategies such as asset mapping and community health workers for preparedness at the local level. The toolkit includes principles and strategies for community engagement and adult learning resources to enhance capacities of responders and community members to implement the CR toolkits in partnership. Resources include a Web-based tool to identify local resources and vulnerabilities related to emergencies and a community health worker manual developed by using a community-based participatory research process that will also be used to adapt that manual to assets, needs, and culture of particular communities in the pilot demonstration described in the next section.

Community Resilience Toolkit and Preparedness Package (Enhanced Standard Practice), Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience Initiative.

| Preparedness Package—Enhanced Standard Practice |

| A public health nurse or health educator from the LACDPH will present 6 preparedness modules (referred to as the “preparedness package”) and accompanying resources. Together, the involved community stakeholders will build their understanding of the resources available to individuals and families in the communities and groups they represent. |

| 1. Individual and family preparedness—Includes instructions how to make a disaster plan, keep supplies, stay informed of disaster status updates, and next steps for preparedness |

| 2. Special considerations for preparedness planning—Information on how to prepare special populations for disasters including kids, animals, people with access and functional needs, and seniors |

| 3. Community emergency response teams (CERTs) and neighborhood watch—Information on CERTs and neighborhood watch groups, their roles and responsibilities, and how to get connected locally |

| 4. Communication tools for neighbors—Brief overview of Map Your Neighborhood and NextDoor, which are materials for mapping a resources in a community |

| 5. Local nonprofits, faith-based organizations, and small businesses in disasters—Disaster planning and emergency survival guide for nonprofits, faith-based organizations, and small businesses |

| 6. Donating and volunteering in disasters—Guidance on how to donate and volunteer in a disaster situation to really help and avoid making things more difficult for organizations in providing assistance |

| Community Resilience (CR) Toolkit |

| A public health nurse from the Department of Public Health will introduce community stakeholders to a Community Resilience Toolkit and collaborate with local coalitions on developing a community resilience plan. The CR coalitions will also have available the toolkits from the enhanced standard preparedness intervention. |

| 1. Psychological first aid—“Listen, protect, connect,” a psychological first aid model for use by lay persons to provide practical and social support and linkages to mental health services in emergencies |

| 2. Community mapping—A tool for use by local leaders to identify capacities to support CR programs and respond to emergencies and to locate vulnerable groups and identify risk factors for emergencies and public health threats |

| 3. Community engagement strategies—Includes principles of community engagement for CR and real life examples contextualizing these principles and strategies |

| 4. How to develop community leaders—Resources for CR leaders from responder and other community agencies |

| 5. Training community field workers—Tools for responder and community agency field staff for training of communities in CR |

Note. LACDPH = Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Pilot Demonstration

On the basis of the framework, toolkit plan, and further information and feedback gathered from the workgroups and community meetings, the Steering Council outlined a 3-year pilot demonstration with the major features described in the next paragraphs.

Community selection.

Los Angeles County is divided into 8 service planning areas (SPAs) of 1 million to 1.5 million people. Each has different geographic features, disaster risks, populations, and service infrastructures. The Council included all 8 SPAs at community members’ request and requested SPA leaders to identify 3 to 5 candidate neighborhoods from which 2 would be selected and randomized to enhanced individual and family preparedness or CR resources. The design is based on a multisite, participatory public health randomized trial.41 The Council identified criteria for candidate communities:

population size 30 000 to 40 000 to increase feasibility of engagement;

including at least 30% underresourced groups, such as low-income racial/ethnic minorities;

shared identity as a “community” and have at least 2 of the following: local business community, schools, fire and police departments, community clinic or hospital, evidence of engaged CBOs or civic leaders;

an existing local neighborhood coalition; and

across communities, diversity in disaster risk, such as level and type of disaster (earthquake, flood, or fire) and culture or ethnicity of the population.

Enhanced standard practice interventions.

The Council considered a “usual practice” control, but community input suggested it would not generate commitment to participate, so an enhanced “best-practice” model supporting individual and family preparedness was specified. In addition, we will track indicators of CR for the county as a whole, to better understand usual practice across Los Angeles County’s 88 cities and unincorporated areas.42 Enhanced standard practice consists of an LACDPH-sponsored annual preparedness campaign and leadership by SPA-level nurses working with a neighborhood coalition to facilitate supported by ENLA leadership. Intervention resources are outlined in the box on the next page.43 The LACDPH will provide nurse facilitators supported by LACDPH and $15 000 per community for trainings.

Community resiliency.

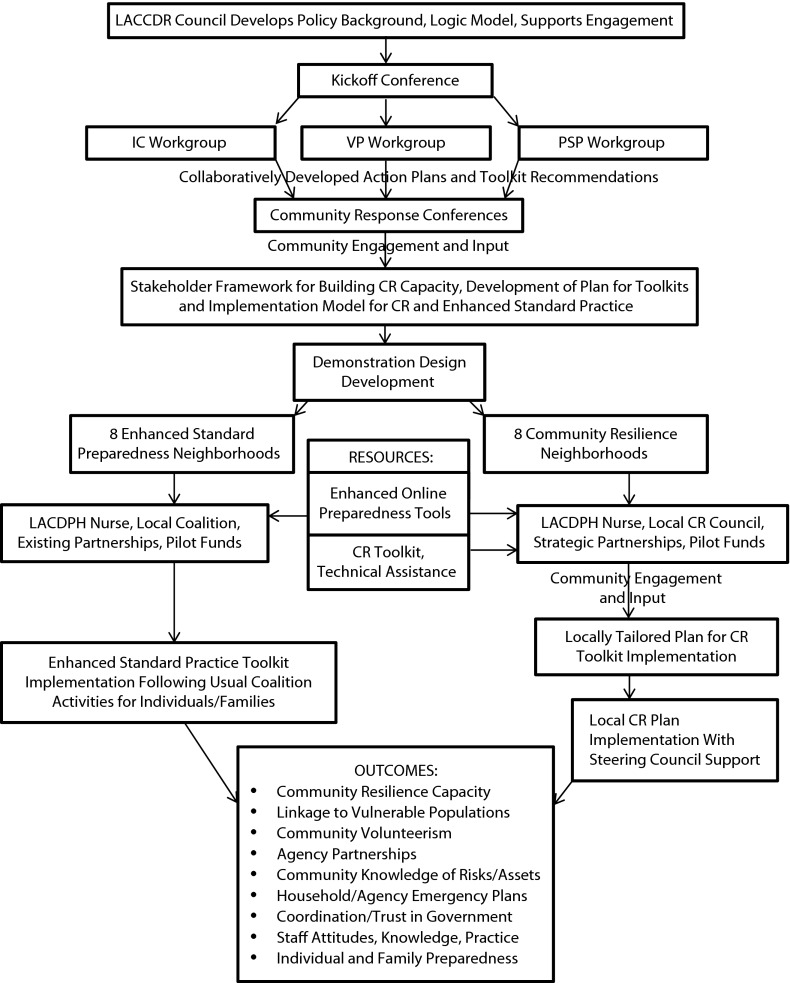

The Council used workgroup feedback and models from previous CPPR initiatives24,26,44 to develop an implementation plan for the CR toolkits (Figure 2). Over 4 months, within each community a public health nurse will work with an existing neighborhood coalition to review the toolkit and develop a written implementation plan. The plan will include such details as trainers, venues, and strategies to engage vulnerable groups across the 11 community sectors in the Centers for Disease Control’s Public Health Preparedness Capabilities.37 In each community, the draft plan will be presented in a local community forum for feedback followed by implementation supported by the coalition and LACDPH and $15 000 per year to support trainings or other needed resources to implement the CR toolkits described previously, including locally tailored public health campaigns, community hazard and asset mapping, training of CR health workers and training of community leaders, health workers, and emergency responders in PFA (see the box on the next page).

FIGURE 2—

Vision to valley: how the vision phase shaped the implementation plan of the Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience initiative.

Note. CR = community resilience; IC = information and communication; LACCDR = Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience; LACDPH = Los Angeles County Department of Public Health; PSP = partnerships and social preparedness; VP = vulnerable populations.

Evaluation design.

The Council proposed a mixed-methods evaluation of the comparative effectiveness of the CR and enhanced standard practice interventions in 16 communities and an evaluation of how key CR indicators change over time across Los Angeles County. The design is group randomization at the neighborhood level within SPA with attention to inclusion of diverse populations across SPAs. Evaluation questions are

What are the benefits of implementing CR programs over enhanced individual or family preparedness practice?

What are processes at the agency, leader, and field-worker levels that promote uptake of CR toolkits?

What are facilitators and barriers at the individual, agency, and community levels for achieving CR?

What components of the toolkit are most feasible and effective?

What are the costs to communities of implementing CR relative to enhanced standard preparedness? and

How do the demonstration and broader policy trends shape the evolution of CR across Los Angeles County?

Key outcome measures.

At the community level, key outcome measures include development of local capacity (e.g., trained leaders) and integration of CBOs into disaster planning. At the agency level, key outcome measures include improvements in preparedness capabilities, development of partnerships between CBOs and responder agencies, knowledge and use of organizational assets for CR, and costs and resources required to implement programs. At the individual level, key outcome measures are knowledge and use of resilience practices and awareness of CR goals and resources.

Data collection strategies.

The data collection strategies include

organizational surveys,

stakeholder interviews,

records kept by public health and responder agencies,

periodic telephone surveys of households in participating neighborhoods and comparison with data across Los Angeles County from public health surveys,

structured observations of field activities,

attendance records and feedback surveys from trainings, and

records kept by agencies after public health threats and disaster events.

Examples of workgroup feedback into design.

Community members raised concerns about ethnic minorities’ trust in randomization but recognized that it would ensure fairness of resource allocation. Leaders from LACDPH noted the importance of LACDPH leadership buy-in, leading to a LACDPH leadership kick-off conference. Some members were concerned that communities might be selected without sufficient infrastructure to support CR. Others suggested inclusion of rural communities and those at risk for wildfires; these concerns influenced selection criteria and priorities. The issue of trust in government responders led to a recommendation for health worker training with responder and community coleaders. Because of the diversity of Los Angeles County communities, workgroup members prioritized getting to know local context, which was responded to through a participatory approach to asset mapping. Ongoing discussions with public health nurses helped to identify challenges to implementation including the need for practical support for nurses in community engagement, technical assistance in use of the toolkit, and flexibility in timelines. Participant input into evaluation design included the importance of tracking broader policy changes promoting CR and including outcomes for community members. Orientation meetings for public health nurses who would facilitate each intervention arm in local communities for the demonstration commenced in January 2013.

DISCUSSION

Community engagement is essential to advancing CR goals but few operational models exist through public health departments. To fill this gap, we applied the structure, principles, and framework of the CPPR “vision” stage to plan a CR initiative in Los Angeles County. This led to clarifying stakeholders’ conceptual framework for developing CR capacity, developing intervention toolkits, and designing a pilot demonstration to compare implementation of resources to support CR versus enhanced public health practice for individual and family preparedness. We found that CPPR was well-suited to bringing community engagement principles into disaster planning, given that all tasks were completed in 18 months with extensive stakeholder input. We found that concrete strategies such as pairing community and academic cochairs, reflection sheets to ensure community input and responsiveness, and use of community engagement exercises helped achieve support for collaboratively developed action plans while building relationships that will improve implementation. Across groups, the use of visioning exercises allowed participants to understand each other’s goals and informed the Council for planning the toolkit and aligning people to action plans. Larger feedback conferences developed agency buy-in and identified gaps, such as the need to increase commitment of administrators. Authorizing a work group to lead community engagement was an effective strategy to support development of this focus across responder agencies while engaging community partners.

The participatory approach and 2-way knowledge exchange inherent to CPPR led to many modifications of the CR toolkit and demonstration design, including a greater focus on trust building, assets of communities, capacity building through team leadership, and a focus on inclusion of vulnerable populations. The discussions in conferences and workgroups helped to fill a key goal for agencies to network in learning about preparedness.

Nevertheless, we faced challenges in implementing a partnered approach. Much of traditional emergency preparedness is conducted “top-down,” but immediate response in the first 72 hours and long-term recovery falls on communities following a “bottom-up” approach. A central message in preparedness training is for communities to be prepared to survive for a period of time on their own, but this message is not necessarily delivered to communities predisaster or coupled with a long-term commitment by responders to assist them in preparing. There can thus be a real or perceived disconnect between the goals and approach of preparedness initiatives and the needs of communities to respect their priorities. An awareness of this gap led to marked shifts in how CR was approached—for example, developing a glossary of terms or grid of responder agencies to promote knowledge exchange or proposing paired responder and community trainers.

Traditional responder agencies noted that it was a substantial shift to focus on agency relationships, community context, and long-term engagement. Yet we found that some models for collaboration existed within responder agencies. One example offered by an emergency management officer was his collaborating alongside community members to paint over neighborhood graffiti. By building on such examples, it became feasible to shift the dialogue toward community engagement. For community members, trust in government responding agencies was a central concern but views shifted as members became more familiar with preparedness content and responders through workgroups.

The demonstration design addresses this responder–community tension by comparing best-practice individual and family preparedness and CR approaches. A limitation of this design is the lack of a true usual practice control, partially addressed by a plan to track selected CR and preparedness indicators across the county. The outcomes framework emphasizes building capacity for agency partnerships in preparedness across public health and other responder agencies and CBOs, community stakeholder knowledge of programs, and evidence from process notes of application of community engagement principles. By planning an initiative to build capacity and generate data on comparative effectiveness of alternative preparedness paradigms, we hope to promote commitment to community participation in the demonstration and to sustaining programs identified as effective, while informing public health policy and practice through evidence.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grant 2U90TP917012-11), the National Institutes of Health (research grant P30MH082760 funded by the National Institute of Mental Health), and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (70503).

The authors thank all workgroup and Steering Council members including Brittney Weissman, Benjamin Bristow, Mariana Horta, Alexa Punzalan, Patrina Haupt, and Gillian Pears for their commitment to the project.

Note. The findings are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funders.

Human Participant Protection

The Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience project was approved by the institutional review boards of RAND (with deferral from University of California, Los Angeles) and Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

References

- 1.Galea S, Ahem J, Resnick H et al. Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(13):982–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa013404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norris FH, Friedman M, Watson P, Byrne C, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. 60,000 disaster victims speak: part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65(3):207–239. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acosta J, Chandra A, Feeney KC. Navigating the Road to Recovery: Assessment of the Coordination, Communication, and Financing of the Disaster Case Management Pilot in Louisiana. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corp; 2010. TR-849-LRA. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandra A, Acosta J. The Role of Nongovernmental Organizations in Long-Term Human Recovery After Disaster: Reflections From Louisiana Four Years After Hurricane Katrina. Vol 277. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corp; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandra A, Acosta JD. Disaster recovery also involves human recovery. JAMA. 2010;304(14):1608–1609. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hobfoll SE, Watson P, Bell C et al. Five essential elements of immediate and mid-term mass trauma intervention: empirical evidence. Psychiatry. 2007;70(4):283–315. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2007.70.4.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Motoyoshi T, Takao K, Ikeda S. Determinants of household- and community-based disaster preparedness. Jpn J Soc Psychol. 2008;23(3):209–220. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Troy DA, Carson A, Vanderbeek J, Hutton A. Enhancing community-based disaster preparedness. Disasters. 2008;32(1):149–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2007.01032.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Disaster Recovery Framework. Washington, DC: Federal Emergency Management Agency; 2011. pp. 1–116. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Health Security Strategy of the United States of America. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pfefferbaum R, Reissman D, Pfefferbaum B, Wyche F, Norris F, Klomp R. Factors in the Development of Community Resilience to Disasters. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schreiber M, Pfefferbaum B, Sayegh L. Toward the way forward: the national children’s disaster mental health concept of operations. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2012;6(2):174–181. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2012.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masten A, Obradovic J. Disaster preparation and recovery: lessons from research on resilience in human development. Ecology Soc. 2008;13(1):9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfefferbaum B, Pfefferbaum R, Norris F. Community Resilience and Wellness for Children Exposed to Hurricane Katrina. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norris FH, Stevens SP, Pfefferbaum B, Wyche KF, Pfefferbaum RL. Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(1-2):127–150. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schoch-Spana M, Franco C, Nuzzo JB, Usenza C. Community engagement: leadership tool for catastrophic health events. Biosecur Bioterror. 2007;5(1):8–25. doi: 10.1089/bsp.2006.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayunga JS. Understanding and applying the concept of community disaster resilience: a capital-based approach. Working paper for the Summer Academy for Social Vulnerability and Resilience Building. 2007. Available at: http://www.ehs.unu.edu/file/get/3761. Accessed April 29, 2013.

- 18.Institute of Medicine. Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies From Social and Behavioral Research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones L, Wells K, Norris K, Meade B, Koegel P. The vision, valley, and victory of community engagement. Ethnicity Dis. 2009;19(4 suppl 6):S6-3–S6-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells K, Jones L. “Research” in community-partnered, participatory research. JAMA. 2009;302(3):320–321. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bluthenthal RN, Jones L, Fackler-Lowrie N et al. Witness for Wellness: preliminary findings from a community–academic participatory research mental health initiative. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(suppl):S18–S34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallerstein N. Commentary: challenges for the field in overcoming disparities through a CBPR approach. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(suppl 1):S146–S148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wells KB, Jones L, Chung B, et al. Community-partnered cluster-randomized comparative effectiveness trial of community engagement and planning or resources for services to address depression disparities. J Gen Intern Med. Epub ahead of print May 7, 2013. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2484-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Springgate BF, Wennerstrom A, Meyers D et al. Building community resilience through mental health infrastructure and training in post-Katrina New Orleans. Ethnicity Dis. 2011;21(3 suppl 1):S1-20–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Springgate B, Allen C, Jones C . Post-Katrina Project Demonstrates a Rapid, Participatory Assessment of Health Care and Develops a Partnership for Post-Disaster Recovery in New Orleans. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corp; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Springgate BF, Allen C, Jones C et al. Rapid community participatory assessment of health care in post-storm New Orleans. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):S237–S243. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wennerstrom A, Vannoy SD, III, Allen C et al. Community-based participatory development of a community health worker mental health outreach role to extend collaborative care in post-Katrina New Orleans. Ethnicity Dis. 2011;21(3 suppl 1):S1-45–S1-51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wells KB, Staunton A, Norris KC et al. Building an academic–community partnered network for clinical services research: the Community Health Improvement Collaborative (CHIC) Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1 suppl 1):S3–S17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung B, Jones L, Jones A et al. Using community arts events to enhance collective efficacy and community engagement to address depression in an African American community. J Information. 2009;99(2):237–244. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lizaola E, Schraiber R, Braslow J et al. The Partnered Research Center for Quality Care: developing infrastructure to support community-partnered participatory research in mental health. Ethnicity Dis. 2011;21(3 suppl 1):S1-58–S1-70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung B, Corbett CE, Boulet B et al. Talking Wellness: a description of a community–academic partnered project to engage an African-American community around depression through the use of poetry, film, and photography. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):S67–S78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vargas RB, Jones L, Terry C et al. Community-partnered approaches to enhance chronic kidney disease awareness, prevention, and early intervention. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2008;15(2):153–161. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plough A, Fielding JE, Chandra Aet al. Building community disaster resilience: perspectives from a large urban county department of public health Am J Public Health 2-13;103(7):1190–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chandra A, Williams M, Plough Aet al. Getting actionable about community resilience: the Los Angeles County Community Disaster Resilience project Am J Public Health2-13;103(7):1181–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gillespie DF, Murty SA. Cracks in a postdisaster service delivery network. Am J Community Psychol. 1994;22(5):639–660. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Public Health Preparedness Capabilities: National Standards for State and Local Planning. Washington, DC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bisson JI, Lewis C. Systematic Review of Psychological First Aid. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Psychological First Aid: Field Operations Guide. 2nd Edition. Los Angeles, CA: National Child Traumatic Stress Network and National Center for PTSD; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Psychological First Aid. Bethesda, MD: Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katz DL, Murimi M, Gonzalez A et al. From controlled trial to community adoption: The Multisite Translational Community Trial. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(8):e17–e27. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cities. County of Los Angeles. Available at: http://portal.lacounty.gov/wps/portal/lac/residents/cities. Accessed June 29, 2012.

- 43.County of Los Angeles Emergency Survival Guide. Los Angeles, CA: County of Los Angeles Office of Emergency Management; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung B, Jones L, Dixon E, Miranda J, Wells K Community Partners in Care Steering Council. Using a community partnered participatory research approach to implement a randomized controlled trial: planning community partners in care. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):780–795. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]