Abstract

Background

This focus group study describes motivators and barriers to participation in the Mayo Mammography Health Study (MMHS), a large-scale longitudinal study examining the causal association of breast density with breast cancer, involving completion of a survey, providing access to a residual blood sample for genetic analyses, and sharing their results from a screening mammogram. These women would then be followed long-term for breast cancer incidence and mortality.

Methods

48 Women participated in six focus groups, four with MMHS non-respondents (N=27), and two with MMHS respondents (N=21). Major themes were summarized using content analysis. Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) was used as a framework for interpretation of the findings.

Results

Barriers to participation among MMHS non-respondents were: 1) lack of confidence in their ability to fill out the survey accurately (self-efficacy); 2) lack of perceived personal connection to the study or value of participation (expectancies); and 3) fear related to some questions about perceived cancer risk and worry/concern (emotional coping responses). Among MMHS respondents, personal experience with cancer was reported as a primary motivator for participation (expectancies).

Conclusions

Application of a theoretical model such as SCT to the development of a study recruitment plan could be used to improve rates of study participation and provide a reproducible and evolvable strategy.

Keywords: Focus groups, participation, epidemiology, recruitment, social cognitive theory, breast cancer, mammography, qualitative

INTRODUCTION

Participation in all types of epidemiologic research has been declining nationally since 1970 with the steepest declines after 1990(1). Both internal and external validity can be compromised due to potential selection bias, and findings cannot be generalized to other populations if differences between participants and non-participants are systematic (1–4).

Morton et al.(1) suggests that the declines in participation are attributable to both inconsistent methods of reporting participation as well as to the increase in the number of epidemiologic studies that include specimen collection. A more recent drop in participation rates could also be directly attributable to the complexity of consent forms resulting from the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability (HIPAA) regulations. For example, Woolf et al. (5) reported a 72.9% decrease in patient accrual to the SELECT (chemoprevention RCT with veterans) study after the enactment of HIPAA regulations. Also, nonparticipation can stem from misunderstandings about the procedure or nature of a project (6).

Others have suggested that the decline in participation is most likely attributable to societal factors. La Verda (1, 7) stated that survey and marketing firms have negatively impacted the public's perceptions of surveys altogether by using them to sell goods and services. Findings from the survey and marketing research literature indicate that survey non-participation is related to: 1) topic disinterest; 2) privacy concerns; 3) perceived lack of authority of survey sponsor; and 4) general over-surveying (8, 9). A review by Edwards et al.(10) highlighted personalization (phone calls prior, personalized letter) and incentives as important components to increasing response rates to postal questionnaires. A recent Cochrane review (11) examined 15 studies of methods to increase recruitment in research studies. Effective strategies identified included: the use of monetary incentives, an additional questionnaire at invitation, and treatment information on the consent form. However, given the heterogeneity of the studies included in the meta analysis, the overall conclusion of the review was that it was not possible to generalize these findings and that it is still not possible to predict the effect of most strategies on recruitment. The authors also emphasized that while many strategies have been used to improve recruitment most are not tested or evaluated in a systematic manner. Williams et al. (12) proposed that investigators look beyond individual factors in developing strategies to promote research participation to include efforts to influence social expectations about involvement. In his commentary on Williams (6), Fry (13) acknowledges that more needs to be done to promote research participation, but before doing so, there is a need to better understand the decision to participate in research using an evidence-based approach that accounts for the variability of participation across social groups and research settings such as ‘preferences, personal and structural barriers and enablers, personal and social benefits and costs of participation’ (pg 1458). According to Williams (6), social cognitive theory (SCT) (14) could provide a basis upon which to evaluate the multi-factorial nature of participation in health-related research as it has been used extensively in the public health literature to explain other types of health-related human behavior (15). SCT specifies determinants of behavior and the mechanisms through which such behavior operates from both the individual and his social environment (14).

In SCT, the interplay of the person in his/her environment is referred to as "reciprocal determinism," whereby interaction between the individual, his environment, and the behavior are dynamic, continually interacting, and influencing each other simultaneously. In SCT, the environment refers to external influences on the individual’s behavior, such as social groups, social relationships (i.e., social support), or public policies. Within these three domains (e.g., individual, environment, and the behavior) are many constructs that have been shown to have an influence on health behavior (14). Some key constructs, which can occur in all three domains, are: behavioral capability, self-efficacy (confidence in one's ability to perform a specific behavior;), outcome expectations, expectancies (the value placed on a certain outcome), normative influences, modeling, observational learning, and emotional coping responses. Bandura stresses that an individual’s closest social network, tends to have the most impact on behavior by influencing one’s personal norms and beliefs and by presenting a culture holding its own norms and beliefs. In SCT, these concepts are termed normative influences at the personal and social level. These normative influences control behavior through social and self sanctions and behaviors that that fulfill socially valued norms will be rewarded. The most proximal environment will carry the most influence, even when the norms of one’s immediate network are contrary to those of the larger environment (16).

Participation in the Mayo Mammography Health Study (MMHS)

Declining participation concerns are salient in the case of the MMHS, a large-scale longitudinal study examining the causal association of breast density with breast cancer. The study proposes to identify new markers of breast cancer risk, including genetic markers and density responses to hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Over a three-year period, researchers planned to recruit 20,700 breast cancer-free women who would provide complete risk factor information from a baseline questionnaire, share their results from a scheduled screening mammogram, and grant access to biological samples that would provide DNA for genetic analyses. These women would then be followed long-term for breast cancer incidence and mortality.

Eligibility criteria for the screening cohort included women ages 35 years or older seen in the Mayo Mammography Clinic for a routine screening mammogram between October 2003– September 2006;current residents of Minnesota, Iowa or Wisconsin; no prior history of bilateral mastectomy, implants, or breast cancer; and be English speaking or agree to have a translator or relative assist with forms.

Eligible women were mailed a recruitment packet one week prior to their scheduled mammogram with a maximum of two contacts before being considered non-responders. The packed contained the study cover letter, an informational brochure, a pencil/paper survey, and the consent form (17). As part of the consent process, participants were asked to grant access to left-over blood from an existing or future sample from a routine medical visit. To promote awareness and make participation easier, study investigators also implemented a community-wide media campaign and provided a toll free number for individuals to call for further information or for help in filling out study materials. Women were contacted twice before being considered a non-responder. The toll free line was utilized by prospective study participants on a routine basis to address questions related to filling out enrollment and consent forms, questions about the study purpose, and to provide help with filling out the study survey.

Between 10/1/2003 and 4/12/2004 there were 14475 eligible women with mammograms who received a recruitment packet while at the Mayo Clinic for a mammogram, of which 4797 (33.1%) consented to the study within 2 months of their mammogram. Prompted by the low response rate and a perceived drop of study participation in general at Mayo, this qualitative study assessed motivators and barriers to MMHS participation to better understand how to improve study participation and recruitment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Focus Group Participants

Focus group participants were recruited by telephone to participate in a 90 minute group interview. Women were eligible for the focus groups if they were MMHS respondents (i.e., those who consented to participate in the MMHS study, provided access to a blood sample, and filled out the survey) and MMHS non-responders (i.e., those who had not responded as to their decision to participate in the larger MMHS study at least one month after receiving a second recruitment mailing). However, those who responded to the mailing and actively declined MMHS study participation were not eligible and therefore were not contacted for the focus group per IRB restrictions. In addition, to be eligible for the focus group, the women had to live within 75 miles of the clinic so they could easily travel to Mayo Clinic to participate in the focus group discussion. Women were contacted by phone up to two times to participate in the focus group before being considered a focus group non-responder.

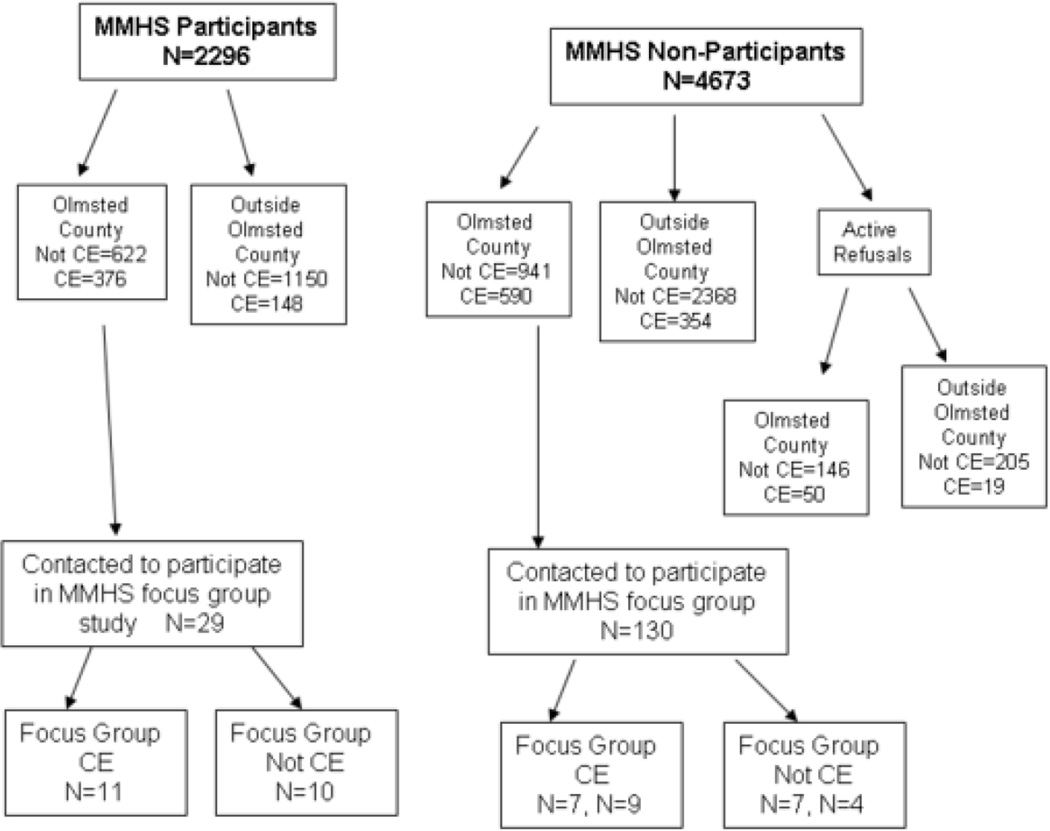

A stratified purposeful sampling strategy (18) was utilized to gather credible information-rich cases from “like groups” of people and that enabled us to explore both motivators and barriers to participation and address concerns that clinic employees might have about the confidentiality of their study information (mammogram results, results of genetic analyses, and survey responses). Women were stratified by their participation in the larger MMHS (i.e., MMHS respondents and MMHS non-respondents) and their employment status (i.e. clinic employee or not a clinic employee). The randomized purposeful design was set-up to achieve a balance of both clinic and non-clinic employees, and MMHS non-responders were oversampled as it was anticipated they would be more difficult to recruit (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of recruitment for MMHS Focus Group Study 4/2004 through 9/2004*

*CE=Mayo Clinic Employee

Procedures

Written informed consent was obtained for the voluntary and confidential focus group session. Dinner and $50 remuneration were provided. Focus groups were selected as the target methodology for this study as these are a useful method for gathering in-depth information from groups of individuals in an expedient and efficient manner, they provide the opportunity for participants to share their experiences with one another and they can stimulate discussion (19). Focus groups were conducted separately for MMHS participants, MMHS non-responders, and for clinic and non-clinic employees. All of the focus groups were conducted by the same moderator and facilitator. The moderator was a cultural anthropologist with formal training in qualitative methods and the facilitator was an MMHS study coordinator with experience conducting qualitative research. Neither the moderator nor the facilitator knew any of the focus group participants prior to their participation in the focus group. The focus group interview was conducted using a semi-structured interview guide by the moderator and the role of the facilitator was to take notes and make observations. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Content domains covered in MMHS respondent and non respondent focus group interviews

| Domain 1 | Review of study recruitment process and materials used in the MMHS. |

| Domain 2: | Discussion of barriers to participation in the MMHS |

| Domain 3: | Discussion of motivators for participation in the MMHS |

| Domain 4: | Discussion of the purpose of the MMHS |

| Domain 5: | Discussion of factors that would make non-responders more likely to participate in the MMHS |

Data Analysis

Audio tape recordings of the focus groups were transcribed verbatim and the written scripts were checked for accuracy. Transcripts were analyzed using content analysis(20). Content analysis of the verbatim transcripts from the six focus groups was used to identify motivators and barriers to participation in the MMHS study. Using NVivo(21), three researchers together coded units of text or statements that conveyed ideas relevant to the research questions and then chose representative labels for these content areas. Generally, the first level of coding included responses to the interview questions. The second level of coding included issues feelings or opinions that were repeated across multiple respondents. Areas of disagreement were identified and definitions of codes were revised and clarified until consensus was reached. Once the codes were identified, the researchers then discussed how these codes related to individual and environmental SCT constructs. The relationship of our findings to SCT is highlighted in the discussion.

RESULTS

Participants

29 participants in the larger MMHS study were contacted to participate in the focus group of which 24 agreed to participate (82.7%). Of the 24 subjects confirmed, 21 actually (72.4%) attended. 130 non-responders to the larger MMHS study were also contacted and 32 (24.6%) agreed to participate. Of the 32, 27 attended (20.8%). The mean age of all focus group participants (63.8 years old) was slightly higher than the average age of all the MMHS cohort participants (58.9 years old).

Six focus groups were conducted: two with MMHS respondents and four with MMHS non-respondents. (Figure 1)

Focus group themes

This section summarizes our findings by the research questions addressed in the focus group interviews. Table 2 highlights the major themes, and includes quotes, or thick description from focus group participants that illustrate our findings.

Table 2.

Overview of themes identified in focus groups of Healthy Women Respondents (N=21) and Non-Respondents (N=27) Recruited for a Breast Cancer Cohort Study (MMHS)*

| Interview Question (MMHS respondent and/or non-respondent focus groups) |

Theme / Related SCT construct |

Representative Quotes from Focus Group Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Study Recruitment Process and Study Materials (both MMHS respondents and MMHS non respondents) | Positive reaction to recruitment packet |

When you say tulips that brings your attention to it. When she called me she said, ‘Do you remember the packet that had tulips on it?’ That brought back that I did receive it. (Non-respondent) The flower kind of lightened it up instead of just plain paper. It was inviting. (Respondent) Yes! It says Mayo Clinic on it, but the words ‘an invitation to participate,’ that is what got my attention when I got this letter…Like I said, I like flowers and I like purple. (Non-respondent) |

| Survey too long and time consuming |

What turned me off was the thing that we were to fill out. It was the same stuff that they asked when you go to a doctor…you get it…you fill it out at home and bring it in. (Non-respondent) It is just a constant fill out of stuff that you think, ‘Oh, who cares if I eat broccoli three times a week?’ (Non-respondent) |

|

| Language in consent form confusing |

I think this could have been written better…dumbing it down…this is more scientific language than we are used to reading… I feel like this is a journal. (Respondent) Why would you want to read through all of it? I’m not really interested…a lot of paragraphs were really cold information that I’m really not interested in. (Non-respondent) I don't think it really tells you that. They don't really give you the facts, they sort of talk around it so you can't really say. That is just how they do it. (Non-respondent) |

|

| Mayo employment status did not lead to concerns about confidentiality |

…I was particularly interested in it because I thought in certain cases they could do mammograms in some other way than they do now. Also, we as former Mayo employees or employees now, we want to do this for the clinic. (Non-respondent) This may sound strange, but I raised five children alone. Mayo was very good to me as far as the benefits, so on and so forth. When I first started doing any of the studies it was really to almost say thank you to Mayo. There were things I couldn’t do but that was one of the things I could do. (Respondent) …I think so many of us worked at Mayo and we kind of really know the system and have trust in it. (Respondent) |

|

| Understanding of Purpose and Requirements of Study (both MMHS respondents and MMHS non respondents) | Purpose of study was not clear |

I thought it was being used for DNA. (Respondent) How breast tissue changes in the genes that process estrogen. (Respondent) I think it is to try to figure out is there a higher prevalence if you exercise or if you eat certain thinks. They will come at it from different angles. It’s not just if you exercise – it is like it may not even be what causes cancer. Who knows? (Non-respondent) I think I just read where there was going to be a blood draw at a normal time when you have your blood drawn anyway which is just an extra sample. So it added a little extra cost to you. (Non-respondent) I think when I read it, it said we usually do one yearly blood draw, and I thought is that going to be an extra appointment set up, worked into your day? (Non-respondent) |

| Confusion about study duration Related SCT constructs: behavioral capability, self-efficacy, expectancies, and outcome expectations |

Well maybe this is a revolving door project, depending on what they find they would proceed to do this or that. But then that should be clarified too. (Non-respondent) …It seemed to me you open the page and if it was clearly spelled out exactly what the study entails, you would have this blood test, this mammogram and amen, you are done! Rather than still leafing through here thinking what am I really going to be doing? I still haven’t really found it. (Nonrespondent) |

|

| Motivators to participation (MMHS respondents only) | Personal connection to cancer |

I’m the same age my mom was when she died of breast cancer…Whatever somebody can learn from my history or my mammograms, or my blood, if it will help down the line to improve things, that is important. I enjoyed doing research in breast cancer and mammography in particular because I have several friends who have had breast cancer and gone through chemo. I think if we can do something so it could be picked up earlier and treated better…. That is part of my reason, too. My mom had both breasts removed. My mom died of breast cancer about a year ago. |

| Perceived value of participating |

I feel that research is very important and also because I have had some cancer in my family and I know a lot of good friends and neighbors who have done research at Mayo. Well, no matter the field, I feel that without research studies and the results from those, progress just won’t be made. |

|

| Strong trust/connection to Mayo Clinic Related SCT Constructs: | I have gone to Mayo since 1958 when I moved here. I haven’t gone anywhere else. I have nothing against the others, but I feel at home at Mayo. I volunteered for 14 years here. This is home. | |

| Environment, Situation, Outcome Expectations, Emotional coping responses, |

This [Mayo Clinic} is the only place I have gone. Another thing I’m thinking is knowing that Mayo will guard my confidentiality…with Mayo, I feel comfortable that if your information is given to an outside group, that everything would be okay. My doing this for the clinic would be because of my affection for the clinic. Mayo is ours! I’m very comfortable being strongly affiliated with Mayo. I have that certain bias or comfort level with this study you have conducted. |

|

| Barriers to participation (MMHS non respondents only) | Procrastination |

I appreciate people trying to find out better ways to serve women with their health problems. I did have every intention of filling it out and sending it back, but time just got away from me I got it; I read through it and the time that I got it, I believe it was when I just starting working on a new job, nights, and I just kind of put it off to the side and just never got back to it. I laid it down and couldn’t find it again! It got in a pile of papers and got lost! Yes, and I just don’t recall what they were, but I think last, probably…well, I know I had my appointment in June, so I received it about that same time. I thought’ I’ll never get this done before I go in,’ but I did start filling it out and it is still in the drawer! |

| Lack of perceived value | We were supposed to leave on a trip to California and I thought I can’t deal with this now…; When I came home I was no longer interested in really doing it. | |

| Perceived difficulty of survey |

I did fill out the survey, but there were questions that I don’t have the immediate answers and it was more of a dates problem…I wanted to do the correct answer I thought ‘this is a snap, I can do this.’ But it went on and on and on. I don’t remember seeing things as black and white, but I didn’t really know. Again, when she said that about no place to comment, there should be room to write the ‘I don’t know part and this is why.’ I don’t know how old everybody is here, but I’m 74 and ‘when did you have the first menstrual cycle?’ Holy smokes! That is a long time ago! ‘Considering the 7 day period a week, how many times, on the average, do you do the following kinds of exercise for more than 15 minutes during your free time?’ Well, I’m retired, I don’t know what they mean by free time? And ‘strenuous exercise, moderate, not exhausting, mild, minimal’--I didn’t agree with that. I would have liked to have written in my own version instead of having to fill in the thing. We climb 40 stairs in our Co-op 3 times a week and walk the halls. It is too hard to answer. |

|

| Fear, e.g., questions about perceived personal and comparative cancer risk |

Number one, it is just cold. When you work with this information daily, you progress to the next question. but also this is very personal. Those two questions that we were just talking about – 18 and 19, those questions don’t bode right. Okay, am I going to be one of those women? I mean, those really were like cold showers sitting there. Do they have to be in there at all? |

|

| Survey overload | As usual, like all Mayo forms that come to us, it is really long. | |

| SCT construct self-efficacy Environment, Situation, Outcome Expectations, Emotional coping responses, | I think that I was having my yearly and I had gotten all the paperwork to fill out for that, and then I got this in the mail about a day later…. 8 pages for this and 4 pages for that. ’I just put it aside. | |

Study recruitment process and materials used in the MMHS

For both the MMHS respondent and non-respondent focus groups, reactions to the recruitment packet were positive and women were responsive to the attractive packaging of the recruitment packet. Women reported reading at least one piece of the recruitment packet, and commented that the materials, particularly the tulip artwork on the information folder and the words, "invitation to participate" printed on the outside envelope, attracted their attention positively.

However, many women expressed complaints regarding the survey, specifically the difficulty of information recall, repetition of solicited clinical information, confusing terms, and length. Several women reported that they stopped taking the survey when it took longer than the estimated 10–15 minutes reference in the cover letter.

In addition, the women had complaints about the language in the MMHS consent form about the blood sample and the protection of their health information, which is standard consent language, used in all research studies. Some were also concerned that by filling out the survey they would be required to undergo further tests or invasive procedures, though this was not the case. They attributed their general lack of understanding to the technical nature of the writing in the consent form which stated that a five-year study was under way, but all that was required for participation was filling out the survey and providing access to the left-over blood sample.

Overall, women expressed that Mayo Clinic employment status did not lead to concerns about confidentiality or affect their decision whether to participate in the MMHS. Loyalty and trust of Mayo Clinic was expressed in both the MMHS respondent and MMHS non-respondent focus groups.

Understanding of the purpose of the original MMHS study

When asked, "What was the purpose of MMHS study, women responded with a variety of answers ranging from “I don’t know. Will you tell us?” from an MMHS non-respondent to “…the factor of breast density and how that leads to breast cancer” from an MMHS participant. Of the 41 textual statements coded under the study purpose theme, 8 statements referenced breast density. When asked about why they would provide access to a residual blood sample; none of the focus group participants provided a rationale and several women expressed concern over having to provide the sample at all.

Motivators to participation among MMHS respondents

MMHS respondents reported altruism, and a personal connection to the Mayo Clinic and to a personal cancer experience through friends or family members, as motivators to participation. Women reported that they felt strongly about participating in research to help find a cure for cancer.

Barriers to participation among MMHS non-respondents

Perfectionism and perceived difficulty in filling out the survey were expressed as primary barriers by the non-respondents. Other barriers were survey overload (receiving too many research surveys), lack of a personal connection (low perceived value of participating), and fear surrounding the mammogram itself that would be heightened through participation in MMHS. Finally, women expressed negative emotional reactions to certain questions on the survey assessing perceived breast cancer risk. For example, the Likert-style questions “How likely do you think it is that you will get breast cancer sometime in your life?” and “Compared to women of your same age and race, what do you think your changes are of getting breast cancer sometime in your life?” were reported to elicit emotional reactions. Women expressed concern not only over thinking about their perceived breast cancer risk, but about why these questions were on the survey and whether they had anything to do with their use of HRT, which was also on the survey.

Factors that would make MMHS non-respondents more likely to participate

Generally, MMHS non-respondents indicated they would be more likely to participate if they were informed of the results and progress with the study and they said they would consider this feedback as a personal benefit to their participation. Women also expressed preferences about survey administration. For example, they would have preferred to receive the survey in the clinic and not by mail, and suggested that having a deadline would have made them more likely to return their survey.

DISCUSSION

This study presents a qualitative in-depth exploration of barriers and motivators to participation in an epidemiological study of mammography and breast cancer. The results provide insight into the complex decision-making processes participants undergo, and suggest strategies and approaches to study recruitment that may increase participation overall and could lead to reductions in selection bias and study validity through the inclusion of a wider range of subjects who may not have a personal association to cancer or who find surveys difficult to complete accurately. Overall, we found that focus group participants reported motivators and barriers to participation at the individual and the environmental level and our understanding of these factors affecting research participation can lead us toward a better understanding of how to intervene effectively to promote participation and reduce barriers in a systematic manner.

First, among respondents, our finding that a personal connection to breast cancer served as a principal driver to decision-making to enroll in the MMHS corresponds well with the literature showing that family cancer history (22) and illness of a friend or relative (23) can serve as motivation for participation in medical research. In the epidemiology literature, a personal connection to breast cancer is reported as a strong motivator for participation in research, as women who participated in a breast cancer prevention trial were observed to be “keenly aware of their responsibility to others” and stated that they took part in hopes of preventing breast cancer in future generations (24). Particular to epidemiologic studies, the title and or topic of women and cancer has been shown to increase participation (25) supporting the view that healthy subjects may contribute if they think they can help find a cure for cancer. This finding is also consistent with SCT as it demonstrates how observation of the cancer experience in friends or family can motivate research participation by enhancing the value placed on advancing breast cancer research (expectancies). Another finding was the level of trust in Mayo Clinic expressed by MMHS study participants. Participants perceived social value in supporting Mayo Clinic exemplified when a Mayo Clinic expressed her primary motivation to participate as an opportunity to “give back” to Mayo.

Alternatively, procrastination was frequently cited as a barrier to participation. The individuals recruited for the MMHS were healthy, breast cancer-free women at population-level risk for developing breast cancer during their lifetime. This represents a category of individuals typically less motivated to participate in disease-ameliorating research (22), and in the context of SCT, the outcome expectations of participation for these women might not be as highly valued as those with a personal connection to cancer. Those who lack a personal connection to cancer need to be provided with a motivator so they see study participation as worth the time and effort taken away from other daily activities. A personal appeal to altruism might be appropriate for these women. For example, if the outside of the envelope read, "Open this if you are interested in helping to prevent breast cancer," this might be motivating. Also, procrastination could have been the result of an emotional coping response to the study subject, whereby subjects didn't want to deal with the subject at hand due to fear of the study topic.

Health behavior theory can also help investigators identify novel strategies to quickly increase one’s interest, outcome expectations, and expectancies related to participation. In this study, all respondents reported being drawn to the tulips on the front of the recruitment packet. How could researchers have devised such a logo that appealed to them with both aesthetic and meaning that linked to a personal connection or social value for participation? Alternatively, how could the tulip logo have been repeated throughout the recruitment materials, in media campaigns, and via incentives (i.e. a tulip pen for breast cancer) to maximize its appeal? The tulip is an excellent example of an effective marketing strategy to draw attention to the study materials, but the behavior of the non-respondents once they opened the envelope provides clear evidence that the tulip doesn't go far enough and social cognitive theory-based strategies are then necessary to move potential participants from interest to participation.

Another barrier was that of "perfectionism," whereby respondents said that if they could not answer a survey item correctly, then they opted to not fill out the survey at all. Survey difficulty was also considered a barrier. The concept of self-efficacy or confidence in one's ability to perform a behavior (such as fill out a survey), from social cognitive theory has been shown as a consistent predictor of behavior across multiple health behaviors (e.g., those who don't have confidence in their ability to fill out the survey will tend not to fill out the survey at all) (26). Studies need to take extra time via pilot testing and careful wording of survey instructions and length limits to enhance the response efficacy of respondents to fill out the survey. Respondents should be given the opportunity to leave an answer blank, fill in a "do not know" category, or have the option and feel comfortable to call a 1–800 number for help. While study coordinators reported that this number was used to provide participants information on the study purpose, to provide help in filling out the survey, and to answer general questions, perhaps this number needs to be highlighted more in the recruitment materials. Survey length was also described as a barrier by our non-respondents. Shorter questionnaire length has been seen to increase participation rates at least 5% in some (25, 27) but not all epidemiologic studies (28). This could illustrate that the title, type of questions and content are simultaneously considered by the individual when considering participation.

Fear was another theme reported by non-respondents. According to SCT, fear can elicit an emotional coping response which would either be study participation or avoidance of the topic altogether (14). It would be difficult to completely eliminate the fear derived from the study topic (breast cancer and mammography); in fact, this type of fear is sometimes utilized as a motivator for screening and disease-preventative behaviors in the public health field (29). However, individuals also reported fear from the study itself (i.e., how and why they were selected to participate, confidentiality issues, and the risk questions, and these fears also served as barriers to participation). Given these concerns, SCT would indicate that this fear be addressed by providing additional support related to problem solving or stress management. This could be provided through improvement in the study materials and ready access to a study coordinator. For example, a clearer explanation of the study purpose, and how/why the woman was selected for participation, may have reduced the overall level of fear, which would have benefits for both respondents and non-respondents. Nonetheless, it was clear from the MMHS respondent focus groups that complete comprehension of the study did not factor greatly into MMHS respondents' decisions to participate. There was very little difference in detailed knowledge about the study between the respondent and non-respondent groups, which corresponds with other studies examining participant and non-participant study understanding (30).

Lack of study understanding is problematic in the context of informed consent. Investigators are now challenged to comply with the HIPAA regulations and wording and balance those requirements with the need to relay the study purpose in a way that a layperson can truly understand. As with other studies (23), focus group participants reported confusion after reading the consent form and this did serve as a barrier to participation or at least gave cause for concern. Some focus groups participants asked that a paragraph explaining the study purpose and the basic concepts presented in the consent form be summarized on the front of the consent in layman's terms, which was provided by the study investigators (see materials). However, from this focus group study, it was apparent that more of a summary is necessary. Further study is needed to find the best way to communicate study purpose and informed consent in both a clear and ethical way (31).

Study limitations and strengths

Those who had actively refused participation in the MMHS were not eligible to participate in this focus group study, due to IRB restrictions on contacting decliners. Thus, our focus groups of MMHS non-responders likely do not represent the views of the resolute decliners. However, those who actively refused formed a very small group (5%) of women approached for participation in the MMHS. Another limitation is that the women were primarily Caucasian which mirrored the makeup of the MMHS itself. This precludes generalizing to other groups such as ethnic minorities and men. Also, while the use of focus groups provided for a wide range of responses and allowed women to share and compare their views on study participation, it could have been inhibiting to some of the women and kept some from discussing issues related to participation that were more personal. We also restricted our study to women living within 75 miles of Mayo Clinic those with a telephone number which limits the generalizability of our findings. Given the time and money required for travel to Mayo for these women, participation in the focus groups was not deemed to be feasible. Finally, both the focus group study and MMHS were conducted at the Mayo Clinic, further limiting generalizability to other large cohort studies.

Strengths of our study include the random purposeful sampling design and the inclusion of both MMHS respondents and non-respondents to obtain reasons for and against participation. Another strength to our analysis was the reliance on SCT (14) to guide interpretation. Future research could focus on a more comprehensive quantitative assessment of SCT to guide not only the interpretation of findings, but also the development of an interview or survey tool. In this fashion, all constructs within SCT could be more rigorously addressed. From our findings, the following recommendations can be made for investigators attempting to maximize recruitment for health research studies: 1) Develop recruitment materials that capitalize on the personal connection to cancer and the expressed loyalty and trust to your research institution [if applicable] using role models that are similar in age, race, and socioeconomic status to the women being targeted for the study; 2) In recruitment materials present potential outcomes (expectancies) that could result from this study that directly affect the participant (i.e. articulate the social value as well as expected outcomes of participating for the participant, their friends and family, the research institution, and the local community); 3) provide clearly defined support and assistance to increase confidence in the participants' ability to complete all aspects of the study including the survey; and 4) keep the survey brief and simplify your recruitment materials. This study underscores the importance of rigorously addressing and evaluating recruitment procedures to maximize motivators and minimize barriers to participation in epidemiological research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part through a grant to Dr. Vachon from the National Cancer Institute, R01 CA 97396. The funding sources had no role in the study design, the interpretation of data, the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. We would also like to thank the study coordinators from the MMHS who contributed to the content of this manuscript and to the recruitment efforts for the MMHS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Morton LM, Cahill J, Hartge P. Reporting participation in epidemiologic studies: a survey of practice. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(3):197–203. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galea S, Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Annals of Epidemiology. 2007;17(9):643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerber Y, Jacobsen SJ, Killian JM, Weston SA, Roger VL. Participation bias assessment in a community-based study of myocardial infarction, 2002–2005. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(8):933–938. doi: 10.4065/82.8.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobsen SJ, Mahoney DW, Redfield MM, Bailey KR, Burnett JC, Jr, Rodeheffer RJ. Participation bias in a population-based echocardiography study. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14(8):579–584. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woolf SH, Chan EC, Harris R, Sheridan SL, Braddock CH, 3rd, Kaplan RM, et al. Promoting informed choice: transforming health care to dispense knowledge for decision making. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2005;143(4):293–300. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-4-200508160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams B, Irvine L, McGinnis AR, McMurdo ME, Crombie IK. When "no" might not quite mean "no"; the importance of informed and meaningful non-consent: results from a survey of individuals refusing participation in a health-related research project. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:59. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.La Verda N, Teta MJ. Re: "Reporting participation in epidemiologic studies: a survey of practice". Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(3):292. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groves RM, Singer E, Corning A. Leverage-saliency theory of survey participation: description and an illustration. Public Opin Q. 2000;64(3):299–308. doi: 10.1086/317990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hox JJ, de Leeuw ED, Vorst H. Survey participation as reasoned action: a behavioral paradigm for survey nonresponse? Bull. Methodol. Sociol. 1995;48:52–67. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, DiGuiseppi C, Pratap S, Wentz R, et al. Increasing response rates to postal questionnaires: systematic review. Bmj. 2002;324(7347):1183. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7347.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mapstone J, Elbourne D, Roberts I. Strategies to improve recruitment to research studies (Cochrane Methodology Review) The Cochrane Database of Methodology Reviews. 2008;(3):1465–1858. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000013.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams B, Entwistle V, Haddow G, Wells M. Promoting research participation: why not advertise altruism? Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(7):1451–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fry CL. A comprehensive evidence-based approach is needed for promoting participation in health research: a commentary on Williams. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(7):1457–1460. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.014. discussion 1461-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baranowski T, Perry CL, Parcel GS. Social Cognitive Theory. In: Glanz K, Lewis Fm, Rimer Bk, editors. Health Behavioral and Health Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection. Preventing AIDS: Theories and methods of behavioral interventions. In: Diclemente R, Peterson J, editors. AIDS prevention and mental health. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17. [Accessed on June, 2007]; MMHS study materials available at: http://mayoresearch.mayo.edu/mammohealthstudy/additional-resources.cfm.

- 18.Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation & research methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. Designing qualitative studies. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krueger RA. Focus Group Kit. Vol. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. Developing Questions for Focus Groups. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knodel J. The Design and Analysis of Focus Group Studies: A Practical Approach, in. In: Morgan Dl., editor. Successful Focus Groups: Advancing the State of the Art. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.NVivo. NVivo Qualitative data analysis software. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shuhatovich OM, Sharman MP, Mirabal YN, Earle NR, Follen M, Basen-Engquist K. Participant recruitment and motivation for participation in optical technology for cervical cancer screening research trials. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99(3 Suppl 1):S226–S231. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lansimies-Antikainen H, Pietila A, Laitinen T, Schwab U, Rauramaa R, Lansimies E. Evaluation of informed consent: a pilot study. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;59(2):146–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schaefer KM, Ladd E, Gergits MA, Gyauch L. Backing and forthing: the process of decision making by women considering participation in a breast cancer prevention trial. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2001;28(4):703–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lund E, Gram IT. Response rate according to title and length of questionnaire. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine. 1998;26(2):154–160. doi: 10.1177/14034948980260020401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. United States of America: W.H. Freeman and Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eaker S, Bergstrom R, Bergstrom A, Adami HO, Nyren O. Response rate to mailed epidemiologic questionnaires: a population-based randomized trial of variations in design and mailing routines. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;147(1):74–82. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffman SC, Burke AE, Helzlsouer KJ, Comstock GW. Controlled trial of the effect of length, incentives, and follow-up techniques on response to a mailed questionnaire. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;148(10):1007–1011. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller SM, Rodoletz M, Mangan CE, Schroeder CM, Sedlacek TV. Applications of the monitoring process model to coping with severe long-term medical threats. Health Psychol. 1996;15(3):216–225. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.3.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verheggen FW, Jonkers R, Kok G. Patients' perceptions on informed consent and the quality of information disclosure in clinical trials. Patient Educ Couns. 1996;29(2):137–153. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(96)00859-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ives NJ, Troop M, Waters A, Davies S, Higgs C, Easterbrook PJ. Does an HIV clinical trial information booklet improve patient knowledge and understanding of HIV clinical trials? HIV Med. 2001;2(4):241–249. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-2662.2001.00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]