Abstract

Background

Osteomyelitis is a complex and heterogeneous group of infections that require surgical and antimicrobial interventions. Because treatment failure or intolerance is common, new treatment options are needed. Daptomycin has broad Gram-positive activity, penetrates bone effectively and has bactericidal activity within biofilms. This is the first report on clinical outcomes in patients with osteomyelitis from the multicentre, retrospective, non-interventional European Cubicin® Outcomes Registry and Experience (EU-CORESM), a large database on real-world daptomycin use.

Patients and methods

In total, 220 patients were treated for osteomyelitis; the population was predominantly elderly, with predisposing baseline conditions such as diabetes and chronic renal/cardiac diseases.

Results

Most patients (76%) received prior antibiotic treatment, and first-line treatment failure was the most frequent reason to start daptomycin. Common sites of infection were the knee (22%) or hip (21%), and the most frequently isolated pathogens were Staphylococcus aureus (33%) and coagulase-negative staphylococci (32%). Overall, 52% of patients had surgery, 55% received concomitant antibiotics and 29% received a proportion of daptomycin therapy as outpatients. Clinical success was achieved in 75% of patients. Among patients with prosthetic device-related osteomyelitis, there was a trend towards higher success rates if the device was removed. Daptomycin was generally well tolerated.

Conclusions

This analysis suggests that daptomycin is an effective and well-tolerated treatment option for osteomyelitis and highlights the importance of optimal surgical intervention and appropriate microbiological diagnosis for clinical outcomes.

Keywords: lipopeptides, Gram-positive infections, bone infections, prosthetic device infections, non-interventional study

Introduction

Osteomyelitis is a complex and heterogeneous group of infections in which the causative pathogens are primarily Gram-positive bacteria, especially staphylococcal species.1 The presence of a prosthetic device (and the temporal relationship to surgery) and whether bone infection is derived from a contiguous focus of infection or from haematogenous spread are crucial determinants for surgical intervention and antibiotic management strategies. Despite the use of various oral and parenteral antibiotics with clinical activity against relevant Gram-positive pathogens, treatment remains challenging and relapse rates after seemingly successful antibiotic treatment may be high.2–4 Specific challenges for antibiotic therapy include the inherent difficulties of tackling deep-seated infections, complications of vascular insufficiency and the involvement of biofilm-forming bacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus.

Daptomycin has excellent bactericidal activity against Gram-positive pathogens, including methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA),5,6 and also retains this advantage in biofilms.7–9 Although it is not licensed for the treatment of osteomyelitis, it penetrates bone effectively10 and has demonstrated efficacy in animal models of chronic MRSA osteomyelitis11,12 and in vitro against MRSA and coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from patients with endocarditis or bone and joint infection,13 with increased efficacy when used in combination with, for example, rifampicin.14 Retrospective analyses have also indicated clinical improvement in patients with osteomyelitis treated with daptomycin.15,16 Additionally, the Infectious Diseases Society of America's 2011 guidelines on the management of MRSA recognize daptomycin as an option for the treatment of osteomyelitis.17

Data from patient registries of real-world clinical experience can be helpful in providing additional information and insights, with the aim of improving outcomes in difficult-to-treat infections, including bone infections. This analysis reports a subset of data from the European Cubicin® Outcomes Registry and Experience (EU-CORESM), a multicentre, retrospective, non-interventional registry for the characterization of daptomycin use and associated clinical outcomes. The objectives of this analysis were to: characterize patients with osteomyelitis who received daptomycin and detail the associated pathogens; evaluate the clinical outcomes, safety and tolerability of daptomycin therapy in these patients; and describe daptomycin prescribing patterns for osteomyelitis.

Patients and methods

Patients and data collection

Investigators retrospectively enrolled patients into the EU-CORE registry who had received treatment with at least one daptomycin dose for infections caused by Gram-positive organisms and for whom all relevant information as required in the case report forms was available. All patients who received daptomycin for inpatient or outpatient treatment of osteomyelitis, with treatment initiated and completed between 19 January 2006 and 14 September 2010, were included in the analysis. Patients with peri-prosthetic joint infections were eligible for inclusion in this analysis, whereas patients with septic arthritis were excluded. Patients were considered to have permanent prosthetic device-related osteomyelitis if infection was associated with a prosthetic joint or temporary prosthetic device-related osteomyelitis if infection was associated with a spacer. Full data collection methods have been described previously.18 Written informed consent that complied with the Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation was obtained if required by the institutional review board or ethics committee and/or local data privacy regulations, and the protocol was approved by the health authority and the institutional review board or ethics committee, as required, in each country.

Demographic, microbiological and clinical outcome data, as well as information on antimicrobial treatment, were collected using a standardized case report form and protocol from patients at 237 institutions across Europe, Latin America, India and Russia. Of these, 77 provided data from patients with a primary diagnosis of osteomyelitis.

Definitions

Clinical outcomes at least 28 days after daptomycin therapy were assessed by investigators using protocol-defined criteria: cure was defined as resolution of clinical signs and symptoms and/or no additional antibiotic therapy necessary, or negative culture reported at the end of therapy. Improved was defined as partial resolution of clinical signs and symptoms and/or additional antibiotic therapy warranted at the end of therapy. Failure was defined as inadequate response to therapy, worsening or new/recurrent signs and symptoms, need for a change in antibiotic therapy, or positive culture reported at the end of therapy; patients for whom insufficient information was provided to allow the response to be determined were classified as non-evaluable.18

Clinical success was used to collectively describe patients with an outcome of cure or improved. The safety and efficacy populations included all patients who received at least one dose of daptomycin; additionally, the safety population included all patients for whom any safety parameters were assessed [the statement that no adverse events (AEs) occurred was considered a valid assessment] and the efficacy population included all patients for whom clinical outcome was assessed.18

Results

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

EU-CORE enrolled 3621 patients in the analysis period 2006–10 and, of these, 220 (6%) had osteomyelitis as the primary diagnosis and were included in both efficacy and safety populations (Table 1). In total, 114 (52%) had non-prosthetic device-related osteomyelitis, 74 (34%) had permanent prosthetic device-related osteomyelitis and 32 (15%) had temporary prosthetic device-related osteomyelitis. The most common sites of primary infection were the knee and hip, which were all implant-related (peri-prosthetic infections). The population was predominantly female and elderly, with predisposing baseline conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, chronic renal or cardiac diseases, and fractures. Ten (4.6%) were receiving dialysis at initiation and at the end of treatment.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with osteomyelitis (n = 220)

| Characteristic | Patients |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| female | 133 (60.5) |

| male | 87 (39.5) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 58.0 (17.25) |

| Age groups | |

| <65 years | 124 (56.4) |

| ≥65 to <75 years | 62 (28.1) |

| ≥75 years | 34 (15.5) |

| Other baseline characteristics | |

| body weight (kg), mean (SD) | 76.7 (18.0) |

| ethnicitya, Caucasian | 197 (95.2) |

| neutropenia at baseline or during daptomycin therapy | 5 (2.3) |

| Renal function | |

| creatinine clearance <30 mL/min | 21 (9.6) |

| receiving dialysis | 10 (4.6) |

| Frequent significant underlying disease (>4%)b | |

| hypertension | 69 (31.4) |

| diabetes mellitus | 59 (26.8) |

| fractures/orthopaedic | 27 (12.3) |

| chronic renal failure | 18 (8.2) |

| cardiac arrhythmias | 12 (5.5) |

| congestive heart failure | 12 (5.5) |

| acute coronary syndromes | 11 (5.0) |

| other cardiovascular disease | 11 (5.0) |

| peripheral vascular disease | 11 (5.0) |

| anaemia (all haematological diseases) | 10 (4.6) |

| alcoholic liver disease, liver failure and chronic liver disease | 9 (4.1) |

| cancer (solid organ) | 9 (4.1) |

| Anatomical site of infection (>4% of population)c | |

| knee | 49 (22.3) |

| hip | 45 (20.5) |

| foot/ankle | 34 (15.5) |

| lower extremity | 33 (15.0) |

| back | 25 (11.4) |

| chest | 13 (5.9) |

| Prior antibiotic therapyd | |

| glycopeptides | 76 (34.5) |

| fluoroquinolone | 62 (28.2) |

| penicillin | 52 (23.6) |

| oxazolidinone | 30 (13.6) |

| cephalosporin | 25 (11.4) |

| carbapenem | 21 (9.5) |

| aminoglycoside | 16 (7.3) |

| tetracycline | 4 (1.8) |

| glycylcycline | 3 (1.4) |

| miscellaneous | 62 (28.2) |

| other | 13 (5.9) |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

aEthnic origin category was missing for 13 patients; therefore, the percentage was calculated as a percentage of the number of values present (n = 207).

bPatients with multiple diseases within a category were counted only once in the total row.

cMultiple sites of infection were possible.

dPatients may have received more than one antibiotic; a patient treated with more than one antibiotic per antibiotic category was counted only once.

Microbiology

Daptomycin was used empirically in 105 (48%) patients, with MRSA being the suspected primary pathogen in 74/105 (70%). Culture results were obtained for 189/220 (86%) before or shortly after initiation of therapy with daptomycin. In cases for which culture results were available the most common primary pathogens were S. aureus (63/189; 33%) and coagulase-negative staphylococci (60/189; 32%).

Previous and concomitant therapy

In total, 168 (76%) patients received antibiotic therapy for osteomyelitis before receiving daptomycin (duration 1–270 days). Glycopeptides were the most common prior treatment. Antibiotic failure was the most common reason for discontinuing prior antibiotic therapy. Of those who received prior glycopeptides, 23/73 (32%) switched because of failure and 14/73 (19%) because of intolerance. Concomitant antibiotic therapy was received by 120 (55%) patients during daptomycin treatment, most commonly fluoroquinolones (34/120; 28%) and carbapenems (24/120; 20%).

One hundred and fifteen patients (52%) underwent surgical interventions as part of their treatment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Concomitant surgical interventions during daptomycin treatment in patients with osteomyelitis (efficacy population)

| Intervention | Number of patients (%)a (n = 220) |

|---|---|

| None | 105 (47.7) |

| Bone debridement | 69 (31.4) |

| Soft tissue debridement | 69 (31.4) |

| Implant removed | 36 (16.4) |

| Incision and drainage | 26 (11.8) |

| Amputation | 7 (3.2) |

| Other | 17 (7.7) |

aPatients may have had more than one surgical intervention.

Daptomycin prescribing patterns

The most frequently prescribed daptomycin dose was 6 mg/kg (123/219; 56%); 46 (21%) patients received >6 mg/kg, 15 (7%) patients received >4 mg/kg but <6 mg/kg, and 35 (16%) patients received 4 mg/kg. Most received daptomycin once daily (205; 94%) and 13 (6%) received daptomycin once every 48 h, as indicated in severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min). One (0.5%) patient received daptomycin three times weekly, an alternative, unapproved dosing interval for patients on three times weekly dialysis (48 h–48 h–96 h). Sixty-four (29%) patients received at least a proportion of their daptomycin treatment as outpatients. The mean total duration of treatment with daptomycin was 28 days (range 1–246 days; median 20 days). Mean inpatient duration of treatment was 20.4 days (range 1–246 days; median 14 days) and mean outpatient duration of treatment was 32.7 days (range 4–89 days; median 29 days).

The primary reason for stopping daptomycin was therapy completion (94 patients; 43%). Eighty-seven patients switched therapy (40%), often to oral antibiotics (69 patients; 31%). Ten (5%) discontinued because of AEs; the reason for discontinuation was recorded as ‘other’ for 12 (6%) and no reason was recorded for 10 (5%). Treatment failure was recorded for seven (3%) patients.

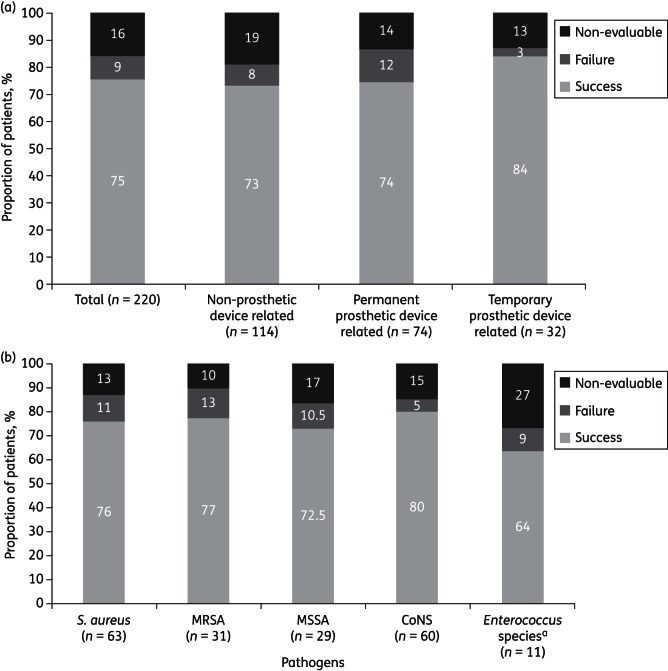

Clinical effectiveness

Clinical success was achieved in 165/220 patients [75%; 50 (23%) were categorized as cured and 115 (52%) were categorized as improved], with treatment failure observed in 19 (9%) and a non-evaluable outcome in 36 (16%; Figure 1a). Treatment failure rates were higher in infections with permanent prosthetic devices (12%) than in infections without prostheses (8%) and infections with temporary prosthetic devices (3%). Among patients with permanent or temporary prosthetic devices, a third (36/106) had an implant removed. There was a trend to higher success rates for both types of prosthetic devices if the device was removed: immediate removal was associated with success rates of 92% (11/12 patients) for temporary devices and 88% (14/16) for permanent devices, compared with successful retention for 80% (16/20) of patients with temporary devices and 71% (41/58) of patients with permanent devices.

Figure 1.

(a) Treatment outcomes by primary infection type (efficacy population). Clinical success: cure or improved outcome. (b) Treatment outcomes by primary infection pathogen (efficacy population). Clinical success: cure or improved outcome. aEnterococcus species includes Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium. CoNS, coagulase-negative staphylococcal species.

Treatment outcomes by primary infecting pathogen are summarized in Figure 1(b). The lowest treatment failure rates (5%) were observed among coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections. Enterococcal infections were limited in number (11 patients), with a higher proportion of non-evaluable outcomes (27%) compared with other pathogens. Similar success was noted between patients with MRSA and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA).

Success rates with first-line (32/50; 64%) versus second-line (133/168; 79%) daptomycin treatment were similar. Similarly, no clear trends related to daptomycin dose were apparent: clinical success was observed in 34/44 (77%) who received ≥4 to ≤5 mg/kg daptomycin, 96/130 (74%) who received >5 to ≤6.2 mg/kg, 23/28 (82%) who received >6.2 to <8 mg/kg and 11/17 (65%) who received ≥8 mg/kg daptomycin.

Safety and tolerability

All 220 patients were eligible for inclusion in the safety population. Of these, 27 (12%) had treatment-emergent AEs: 15 (7%) had treatment-related AEs and 2 (0.9%) had serious AEs considered treatment related by the investigator (renal tubular necrosis and bronchospasm). The most commonly reported treatment-related AE was malaise (three patients; 1%). Ten (5%) discontinued treatment because of an AE, regardless of relationship to daptomycin (Table 3). Four deaths were reported; none was considered treatment-related. The primary causes of death were infections (n = 2) and cardiac disorders with or without renal urinary disorders (n = 2).

Table 3.

Discontinuation of daptomycin treatment because of treatment-emergent adverse events regardless of drug relationship (safety population)

| Primary system organ class preferred term | Number of patients (%) (n = 220) |

|---|---|

| Cardiac failure congestive | 1 (0.5) |

| Nausea | 1 (0.5) |

| Drug intolerance | 1 (0.5) |

| Pyrexia | 1 (0.5) |

| Hypersensitivity | 1 (0.5) |

| Bacterial sepsis | 1 (0.5) |

| Pneumonia | 1 (0.5) |

| Blood CPK increased | 1 (0.5) |

| Renal tubular necrosis | 1 (0.5) |

| Bronchospasm | 1 (0.5) |

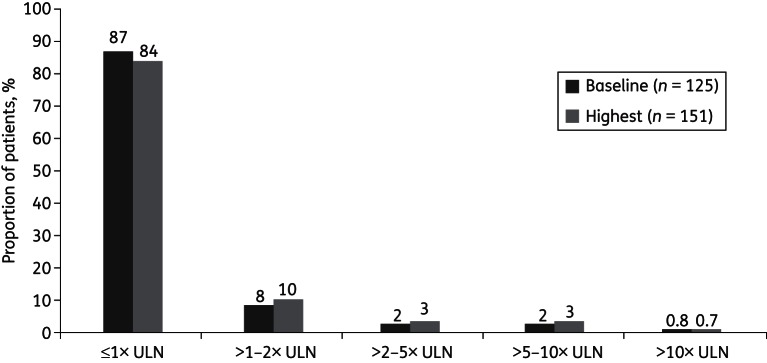

A similar proportion of patients had a creatinine clearance <30 mL/min at the start of therapy (10%) compared with that at the end of therapy (9%). Peak serum creatine phosphokinase (CPK) concentrations were below or equal to the upper limit of normal throughout the analysis period in most patients (127/151; 84%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Baseline and peak serum CPK concentrations (safety population with measurements available). Values were missing or not measured for 95 patients at baseline and for 69 patients on treatment. ULN, upper limit of normal.

Discussion

In this analysis of EU-CORE registry data, 75% of patients receiving daptomycin for osteomyelitis were assessed as clinical successes at least 28 days after treatment. This is notable for such a challenging infection type in a mostly pre-treated population who were switching to daptomycin primarily because of antibiotic treatment failure. Longer-term success rates will become available from EU-CORE with follow-up visits after 1 year and 2 years of treatment. Short-term clinical success rates of 93% and 91% have been reported in patients treated with daptomycin for osteomyelitis in the CORE® registry (US-based Cubicin® Outcomes Registry and Experience).15,19 Another retrospective case review reported cure in 87% of patients with osteomyelitis after completion of daptomycin given as outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy.16

Clinical success was higher in patients with temporary prosthetic device-related osteomyelitis than in non-prosthetic device and permanent prosthetic device-related osteomyelitis, potentially reflecting the advantage of surgical removal of the focus of infection. As prosthesis retention can only be determined as successful after a long follow-up period (in a well-selected population according to standard protocols and guidelines20–22), the reported success rates in prosthesis retention need careful interpretation. Reasons for prosthesis retention and detail regarding debridement were not reported in the case report forms.

Patients undergoing surgery for osteomyelitis associated with an infected prosthesis caused by staphylococci were specifically studied in a recent multinational, randomized, Phase II clinical trial. Once-daily daptomycin at 6 and 8 mg/kg achieved higher clinical success rates in evaluable patients [58% (14/24) and 61% (14/23), respectively] than in patients on the pooled comparator of vancomycin, teicoplanin or a semi-synthetic penicillin (38%; 8/21).23 The optimal daptomycin dose to treat osteomyelitis has not been defined, but doses >6 mg/kg may be advantageous to compensate for low vascularization of bone tissue.24 Initial high-dose daptomycin (10 mg/kg) is currently recommended in guidelines for treatment of several infections caused by MRSA.17 No trend in dose-related outcomes was apparent in this analysis.

The clinical efficacy of daptomycin in osteomyelitis is supported by its pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile. Bone penetration following a single 8 mg/kg dose of daptomycin in patients undergoing joint replacement resulted in local drug levels that were greater than the susceptibility breakpoint of clinical S. aureus isolates: median daptomycin concentrations were 3.1 mg/g in bone and 22.4 mg/L in synovial fluid versus a maximum plasma concentration of 71.3 mg/L.25 Furthermore, in patients with diabetic foot infection complicated with osteomyelitis, free concentrations of daptomycin in bone and subcutaneous adipose tissue after administration of multiple doses of 6 mg/kg were sufficient to treat MRSA and other Gram-positive bacteria.10 The bactericidal activity advantage of daptomycin against biofilm infections compared with other antibiotics has been demonstrated consistently.7–9 However, because the treatment of these types of infection with monotherapy is rarely successful, the importance of using daptomycin in combination with other antibiotics has been recognized, and combination therapy with rifampicin has had high success rates in animal models of biofilm-associated MRSA infections.14

In this analysis, 40% of patients switched therapy from daptomycin. Switch to oral therapy in osteomyelitis is an appropriate and commonly applied strategy if clinical and inflammatory marker improvement has been achieved, infection is controlled and suitable oral therapy is available.26,27 Oral switch is of particular relevance for patients in whom an infected prosthesis has been retained after debridement.28 Daptomycin particularly lends itself to outpatient administration, given its 2 min daily administration time.15,19,29

The data from this EU-CORE sub-analysis suggest that daptomycin is well tolerated in osteomyelitis, with a safety profile that compares favourably with previous reports, including case studies of high-dose daptomycin.18,30,31 Although elevation of CPK levels is well documented with daptomycin,32 peak CPK concentrations compared favourably with the overall EU-CORE population.18 Here, CPK increase was reported as an AE leading to discontinuation in only one case.

This analysis is limited by the retrospective nature of the data and the relatively short follow-up period of 28 days after discontinuation of daptomycin. Long-term follow-up will help in defining the robustness of the presented results. The relatively high proportion (16%) of patients with a non-evaluable outcome in this analysis may reflect the difficulties in assessing short-term response in this complex infection and a reluctance of investigators to ascribe success of treatment after a relatively short follow-up period. It is possible that some implant-related hip and knee infections may have been misclassified as ‘septic arthritis’ and therefore not included in this analysis as a qualifying primary infection. This potential omission raises the possibility that the proportion of prosthesis-related osteomyelitis within EU-CORE may have been underestimated.

Although the inclusive nature of the registry is a strength, demonstrating the diversity of osteomyelitis infections treated with daptomycin in the real world, it is also a weakness with regard to assessing specific treatment responses. Various factors could not be controlled for and could have influenced treatment outcome. These factors included infection types, duration of antimicrobial therapy, surgical management strategies, and the influence of prior and concomitant antibiotic therapy. Improvements to the registry case report forms have subsequently been made to collect additional data, with longer follow-up, from future patients enrolling in EU-CORE.

In conclusion, this analysis suggests that daptomycin is a useful and well-tolerated treatment for osteomyelitis. The optimal dosage, regimen and value of concomitant antimicrobials and the role of surgical treatments in osteomyelitis have yet to be determined. Higher daptomycin doses, >6 mg/kg once daily, as monotherapy or in combination therapy may have potential in difficult-to-treat infections and deserve further investigation in osteomyelitis.

Funding

This study was supported by Novartis Pharma AG. Editorial support was also funded by Novartis Pharma AG.

Transparency declarations

R. A. S. has received funds for speaking and Advisory Board membership from Novartis. K. N. M. has received funds for Advisory Board membership from Novartis. P. V. has received funds for speaking for Novartis. P. G.-K. has received funds for speaking for Novartis. R. P., M. H. and R. L. C. are employees of Novartis Pharma AG and own stocks with the company. T. S. and E. P.: none to declare.

All of the authors were involved in all phases of this analysis; this included enrolment of patients, data analysis and preparation of the manuscript. The authors did not receive honoraria for the preparation of this manuscript.

Editorial support for the authors of this article was provided by Laura Saunderson of Chameleon Communications International. This support encompassed the preparation of a preliminary draft, incorporating authors' contributions and revisions, editing and referencing, all under the direction of the authors. At all stages, the authors have had control over the content of this manuscript, for which they have given final approval and take full responsibility. Novartis Pharma AG enforces a ‘no ghost-writing’ policy.

Acknowledgements

These data were presented in part at the Nineteenth European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Vienna, Austria, 2010 (oral abstract 513).

We acknowledge the work of the EU-CORE investigators and participating institutions. We thank Dr Margaretha Bindschedler for useful discussions.

References

- 1.Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. Osteomyelitis. Lancet. 2004;364:369–79. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16727-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conterno LO, da Silva Filho CR. Antibiotics for treating chronic osteomyelitis in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;issue 3:CD004439. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004439.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazzarini L, Lipsky BA, Mader JT. Antibiotic treatment of osteomyelitis: what have we learned from 30 years of clinical trials? Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:127–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraimow HS. Systemic antimicrobial therapy in osteomyelitis. Semin Plast Surg. 2009;23:90–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marconescu P, Graviss EA, Musher DM. Rates of killing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus by ceftaroline, daptomycin, and telavancin compared to that of vancomycin. Scand J Infect Dis. 2012;44:620–2. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2012.669843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LaPlante KL, Rybak MJ. Impact of high-inoculum Staphylococcus aureus on the activities of nafcillin, vancomycin, linezolid, and daptomycin, alone and in combination with gentamicin, in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4665–72. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.12.4665-4672.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raad I, Hanna H, Jiang Y, et al. Comparative activities of daptomycin, linezolid, and tigecycline against catheter-related methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus bacteremic isolates embedded in biofilm. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:1656–60. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00350-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leite B, Gomes F, Teixeira P, et al. In vitro activity of daptomycin, linezolid and rifampicin on Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. Curr Microbiol. 2011;63:313–7. doi: 10.1007/s00284-011-9980-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaPlante KL, Woodmansee S. Activity of daptomycin and vancomycin alone and in combination with rifampin and gentamicin against biofilm-forming methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in an experimental model of endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3880–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00134-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Traunmuller F, Schintler MV, Metzler J, et al. Soft tissue and bone penetration abilities of daptomycin in diabetic patients with bacterial foot infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:1252–7. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rouse MS, Piper KE, Jacobson M, et al. Daptomycin treatment of Staphylococcus aureus experimental chronic osteomyelitis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:301–5. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lefebvre M, Jacqueline C, Amador G, et al. Efficacy of daptomycin combined with rifampicin for the treatment of experimental meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) acute osteomyelitis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;36:542–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rouse MS, Steckelberg JM, Patel R. In vitro activity of ceftobiprole, daptomycin, linezolid, and vancomycin against methicillin-resistant staphylococci associated with endocarditis and bone and joint infection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;58:363–5. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.John AK, Baldoni D, Haschke M, et al. Efficacy of daptomycin in implant-associated infection due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: the importance of combination with rifampin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:2719–24. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00047-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crompton JA, North DS, McConnell SA, et al. Safety and efficacy of daptomycin in the treatment of osteomyelitis: results from the CORE Registry. J Chemother. 2009;21:414–20. doi: 10.1179/joc.2009.21.4.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larioza J, Girard A, Brown RB. Clinical experience with daptomycin for outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy. Am J Med Sci. 2011;342:486–8. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31821e1e6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e18–55. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez-Ruiz A, Beiras-Fernandez A, Lehmkuhl H, et al. Clinical experience with daptomycin in Europe: the first 2.5 years. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:912–9. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martone WJ, Lindfield KC, Katz DE. Outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy with daptomycin: insights from a patient registry. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:1183–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01824.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandt CM, Sistrunk WW, Duffy MC, et al. Staphylococcus aureus prosthetic joint infection treated with debridement and prosthesis retention. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:914–9. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.5.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meehan AM, Osmon DR, Duffy MC, et al. Outcome of penicillin-susceptible streptococcal prosthetic joint infection treated with debridement and retention of the prosthesis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:845–9. doi: 10.1086/368182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1645–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byren I, Rege S, Campanaro E, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the safety and efficacy of daptomycin versus standard-of-care therapy for the management of patients with osteomyelitis associated with prosthetic devices undergoing two-stage revision arthroplasty. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:5626–32. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00038-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimmerli W. Clinical practice. Vertebral osteomyelitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1022–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0910753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chirouze C, Muret P, Berthier F, et al. Penetration of daptomycin into bone and joint. Abstracts of the Fifty-first Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. Washington, DC, USA: American Society for Microbiology; Abstract A1–1745. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1373–406. doi: 10.1086/497143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Licitra C, Crespo A, Licitra D, et al. Daptomycin for the treatment of osteomyelitis and prosthetic joint infection: retrospective analysis of efficacy and safety in an outpatient infusion center. Internet J Infect Dis. 2011;9 doi:0.5580/215c. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Byren I, Bejon P, Atkins BL, et al. One hundred and twelve infected arthroplasties treated with ‘DAIR’ (debridement, antibiotics and implant retention): antibiotic duration and outcome. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:1264–71. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chakraborty A, Roy S, Loeffler J, et al. Comparison of the pharmacokinetics, safety and tolerability of daptomycin in healthy adult volunteers following intravenous administration by 30 min infusion or 2 min injection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:151–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fowler VGJ, Boucher HW, Corey GR, et al. Daptomycin versus standard therapy for bacteremia and endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:653–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Durante-Mangoni E, Casillo R, Bernardo M, et al. High-dose daptomycin for cardiac implantable electronic device-related infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:347–54. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Novartis Europharm Ltd. Cubicin® (Daptomycin) Summary of Product Characteristics. 2012 http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/17341. (18 January 2013, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]