Abstract

High-density lipoproteins (HDLs) represent a family of particles characterized by the presence of apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) and by their ability to transport cholesterol from peripheral tissues back to the liver. In addition to this function, HDLs display pleiotropic effects including antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic or anti-proteolytic properties that account for their protective action on endothelial cells. Vasodilatation via production of nitric oxide is also a hallmark of HDL action on endothelial cells. Endothelial cells express receptors for apoA-I and HDLs that mediate intracellular signalling and potentially participate in the internalization of these particles. In this review, we will detail the different effects of HDLs on the endothelium in normal and pathological conditions with a particular focus on the potential use of HDL therapy to restore endothelial function and integrity.

Keywords: high-density lipoproteins, endothelium, receptors, proteomics, antioxidant, cholesterol, protease, stroke, cardiovascular, functionality

Introduction

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) diversity

HDLs are heterogeneous particles (Camont et al., 2011), primarily defined by their density, between 1.063 and 1.21, which allows isolation from plasma by ultracentrifugation: HDL2a, HDL2b and HDL3 (HDL1 is not detectable in humans). Concomitantly, characterization of HDL particles by size can be achieved by gradient gel electrophoresis, which separates HDLs into HDL2b, HDL2a, HDL3a, HDL3b and HDL3c. Alternatively, two-dimensional gel electrophoresis allows separation into small pre-β HDLs and large α1-α4 HDLs according to their charge (β and α migration) and size (nm). More recently techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and ion mobility have been used to separate HDLs. The range of techniques used emphasize the heterogeneity of HDL subclasses and data from these different methodologies need to be brought together to conduct prospective studies in order to establish associations between HDL subclasses and cardiovascular diseases. HDLs are composed of lipids (phospholipids, esterified and non-esterified cholesterol, triglycerides) and proteins. Although apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I) is the most abundant protein present, more than 100 different proteins have been reported to be associated with HDL particles (Vaisar, 2012). In addition to the classical ultracentrifugation technique, immuno-precipitation using anti-apoA-I antibodies to capture all HDL particles can be used to isolate HDLs from plasma (McVicar et al., 1984). However, most studies that investigate the effects of HDLs in vitro use plasma HDLs isolated by ultracentrifugation, which represent a pool of all fractions. In certain studies and particularly in vivo, the authors use reconstituted HDLs (rHDLs), which consist of an in vitro combination of apoA-I and phospholipids, producing disc-shaped particles resembling nascent HDL (Newton and Krause, 2002). The apoA-I used for reconstituting HDLs may be either purified from human plasma or produced by recombinant technology.

Different types of endothelium

The endothelium is defined as the inner cell layer of blood vessels including arteries, veins, capillaries and venules, but also lymphatics. Electron microscopic studies have revealed an important structural heterogeneity of endothelium, ranging from a continuous to a fenestrated or discontinuous cell lining, depending on the density of tight junctions, the presence of holes or fenestrae, or even frank gaps between cells (see Aird, 2007a,b). The blood brain barrier (BBB) is an example of a continuous endothelium with a dense network of tight junctions, which is closely associated with pericytes and astrocyte feet. A separate section is devoted to the effects of HDLs on the BBB, in this review. The transport of material across the endothelium is mediated by caveolae and vesiculo-vacuolar organelles (VVO). Whereas caveolae are frequently found in capillary endothelium [except for the BBB, which displays a reduced number of caveolae (Simionescu et al., 2002)], VVOs are most prominent in venular endothelium (Dvorak and Feng, 2001). Different types of endothelial cells can be used in vitro to investigate the effects of HDLs in response to various stimuli. In this review, the cell type used (primary cell culture, cell lines, obtained either from arteries or veins) and the origin (human, animals) will be specified. Furthermore, the extent of confluence in endothelial cell monolayers may induce different responses to the same stimulus, because the presence of tight junctions between endothelial cells critically affects their function, but this information is seldom available in publications.

Endothelial receptors for HDLs

HDLs exert a plethora of beneficial effects on the endothelial layer, which is the focus of the present review, but also on the surrounding tissues. It is important to understand how HDLs induce intracellular signalling from apical receptors of endothelial cells, whether HDL particles can enter endothelial cells and how they reach the subendothelial space.

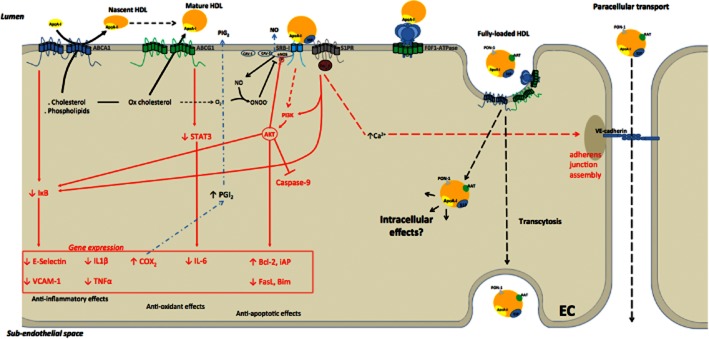

The different endothelial receptors for HDL include the scavenger receptor B type I (SR-BI), the ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABCA1 and ABCG1), and the recently discovered ecto-F1-ATPase (receptor nomenclature follows Alexander et al., 2011). These receptors can mediate intracellular signalling and then trigger or participate in HDL internalization, as summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Different receptors for apoA-I and HDLs and associated intracellular signalling pathways (in red) in the endothelial cell (EC). ABCA1 mediates cholesterol and phospholipid efflux to apoA-I to form nascent discoidal HDL particles. ABCG1 transfers oxidized cholesterol to mature HDL particles. SR-BI, in combination with S1P receptors, mediates various endothelio-protective effects including NO production and induction of survival signalling pathways. Inhibition of NF-κB signalling and activation of Akt represent common pathways downstream to the different HDL receptors for mediation of anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anti-apoptotic effects of HDLs. S1P receptors are involved in the stabilization of adherens junctions. ABCA1, ABCG1 and F0F1-ATPase participate in HDL transport through endothelial cells (transcytosis). The intracellular fate of internalized HDL particles and associated proteins [such as α-1 antitrypsin (AAT)] requires further investigation.

SR-BI

CO36, which was the first identified receptor for HDL (Calvo and Vega, 1993; Acton et al., 1994), due to its homology with CD36, which is able to bind HDL particles, but devoid of the associated intracellular signalling that characterizes the response of SR-BI to HDL binding (Saddar et al., 2010). Whereas the role of SR-BI in cholesterol efflux from macrophages is not clear, in particular due to species-related differences between mice and humans (Chen et al., 2000b; Larrede et al., 2009), endothelial SR-BI signalling in response to HDLs clearly leads to production of vasculo-protective NO (Yuhanna et al., 2001). Recently, Zhang et al. reported that SR-BI signalling was involved in HDL-induced cyclooxygenase 2 expression and PGI2 production by endothelial cells (Zhang et al., 2012). The latter is a strong vasodilator and potent inhibitor of platelet adhesion (Linton and Fazio, 2002). SR-BI also binds to other ligands such as phospholipids, very low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and modified LDL (oxidized or acetylated) (Krieger, 2001). The endothelial effects associated with binding of these ligands to SR-BI are not well documented. The C-terminal transmembrane domain of SR-BI is also regarded as a plasma membrane cholesterol sensor, necessary for its downstream intracellular signalling (Saddar et al., 2013).

ABCA1

Patients with Tangier disease are characterized by an HDL deficiency syndrome, such that they accumulate cholesterol in tissue macrophages and are more prone to atherosclerosis (Calabresi and Franceschini, 1997). Based on studies using cells from these patients, several groups have identified a member of the ABC transporter family, ABCA1, as the protein involved in defective apolipoprotein-mediated lipid removal in these patients (Bodzioch et al., 1999; Brooks-Wilson et al., 1999; Rust et al., 1999). ABCA1 mediates cholesterol efflux from macrophages to apoA-I via two possible mechanisms: (i) at the plasma membrane (Venkateswaran et al., 2000); or (ii) after binding and internalization of apoA-I into late endosomes to finally be re-secreted by exocytosis after being enriched with cholesterol (Takahashi and Smith, 1999). ABCA1 is also expressed by human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) and was reported to be up-regulated by LDLs (Liao et al., 2002). In these cells, overexpression of ABCA1 increased cholesterol efflux. Similarly, in a model of hypercholesterolemia in pigs, induced by 2 weeks of high fat (15%) and cholesterol (1.5%) diet, Civelek et al. (2010) showed that the ABCA1 gene was up-regulated in endothelial cells, independently of the aortic territory (in both atherosusceptible and atheroprotected regions).

ABCG1

The role of a related transporter protein, ABCG1, in lipid metabolism was investigated because of its high sequence homology with ABCA1. It was suggested to be a regulator of macrophage cholesterol and phospholipid transport (Klucken et al., 2000). ABCG1 expression is induced in macrophages by modified LDL (oxidized, acetylated and enzymatically modified LDL (Schmitz et al., 2001)), at least in part via the liver X receptor subfamily of nuclear hormone receptors in response to oxysterols (Venkateswaran et al., 2000). ABCG1 is also expressed by endothelial cells (HUVECs and HAECs), but is not associated with cholesterol efflux to HDL3 (O'Connell et al., 2004). In contrast, ABCG1 was reported to mediate cholesterol efflux and in particular that of 7-ketocholesterol to HDLs in a different study using HAECs (Terasaka et al., 2008). These authors suggest a role for ABCG1 in the protection of endothelial dysfunction of mice fed with a high-cholesterol diet via a reduced inhibition of NO production (Terasaka et al., 2010).

Ecto-F1-ATPase

Ecto-F1-ATPase, a cell surface enzymatic complex related to mitochondrial F1F0-ATP synthase, was first discovered by Martinez et al. (2003) as a high affinity receptor for apoA-I in hepatocytes and shown to trigger endocytosis of HDLs. In this HDL endocytosis pathway, apoA-I binds to the β-chain of ecto-F1-ATPase leading to hydrolysis of ATP to ADP. Extracellular ADP activates the P2Y13 receptor, which stimulates, in turn, the uptake of holo-HDL (proteins + lipids) via an unknown low affinity receptor, distinct from the classical HDL receptor, SR-BI (Jacquet et al., 2005; Fabre et al., 2010).

Expression of ecto-F1-ATPAse at the surface of endothelial cells (HUVECs) was demonstrated in 1999 by Moser et al. (1999) who showed that the α subunit could bind angiostatin and mediate its anti-angiogenic effects. Ten years later, endothelial ecto-F1-ATPAse was shown to bind apoA-I and to mediate inhibition of apoptosis induced by serum deprivation (in HUVECs) (Radojkovic et al., 2009). This receptor for apoA-I was recently involved in uptake and transport of HDL and lipid-free apoA-I by bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAEC) (Cavelier et al., 2012).

How do HDLs reach the sub-endothelial space?

The best documented cardiovascular protective effect of HDLs is their capacity to remove excess cholesterol from the peripheral tissues and to transport it back to the liver, for its subsequent elimination in the bile. This is called reverse cholesterol transport (RCT). The first step of RCT is to transfer cholesterol from lipid-laden cells (including macrophages or smooth muscle foam cells) to HDLs. RCT also plays an important role in mediating endothelial protective effects, by removing cholesterol and oxysterol and by triggering intracellular signalling pathways. The involvement of RCT in the protection of endothelial cells by HDL has recently been reviewed (Prosser et al., 2012).

The exact mechanisms governing RCT from foam cells are still a matter of debate, in particular, whether HDLs need to enter the cells or not in order to accept cholesterol should be investigated in more detail:

One theory suggests that cholesterol efflux from foam cells towards HDLs involves an endocytotic pathway of mature HDLs and lipid-free apoA-I to reach the subendothelial space of the arteries (Takahashi and Smith, 1999).

The other main theory suggests that HDLs dock with their cell surface receptor, which triggers a signal leading to the delivery of cholesterol from intracellular membranes to HDLs, without the necessity for HDL internalization (Slotte et al., 1987). Caveolin-1 appears to play an important role in this mechanism and this protein is the main structural component of caveolae that have been implicated in transmembrane transport and intracellular signal transduction (Anderson, 1998).

However, in order to reach the foam cells within the arterial wall, circulating HDLs have to cross the endothelial layer either through endothelial cells, via a transcellular route (transcytosis), or between them (paracellular) route, unless the endothelial lining is disrupted.

von Eckardstein and Rohrer (2009), who studied the interaction of both mature HDLs and apoA-I with endothelial cells, extensively analysed the process of transcytosis. They showed that BAECs cultured on porous inserts, bind, internalize and translocate HDLs from the apical to the basolateral compartment. HDL transcytosis involves two endothelial cell surface receptors that are SR-B1 and ABCG1 (Rohrer et al., 2009), but not ABCA1, which was previously found to modulate lipid-free apoA-I transendothelial transport (Cavelier et al., 2006). Lin et al. (2007) also reported that rat aortic endothelial cells express ABCA1 and showed that this transporter was able to modulate HDL-mediated cholesterol efflux in association with caveolin-1. They showed that ABCA1 and caveolin-1 are internalized by these cells after HDL incubation, but do not colocalize (Kuo et al., 2011). The intracellular fate of HDL after uptake is not yet well characterized. Using immunoelectron microscopy, the same group reported, in rat aortic endothelial cells incubated with HDLs, that caveolin-1 was found in plasmalemmal invaginations and colocalized with HDL in cholesterol-loaded cells (Chao et al., 2003). Only a very few free HDL particles were observed in the cytoplasm. Thus, these authors concluded that HDLs probably dock with caveolin-1, which is part of a specific membrane domain, that is within caveolae, and thus stimulate cholesterol efflux (Chao et al., 2003). Arakawa et al. (2000) demonstrated the involvement of caveolin-1 and ABCA1 in cholesterol enrichment of HDLs in the human monocytic leukaemia cell line, THP-1. They showed that apoA-I allowed removal of intracellular cholesterol and phospholipid after treatment by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), which induced expression of both caveolin-1 and the ABCA1 transporter.

Another receptor that could play a role in endothelial endocytosis of HDL is the β-chain of cell surface F0F1-ATPase. This receptor, initially identified as a hepatic receptor for apoA-I able to trigger HDL internalization by hepatocytes (Martinez et al., 2003), was recently shown to mediate apoA-I binding and subsequent internalization of HDLs by BAECs (Cavelier et al., 2012).

Another pathway for HDL particles to reach the subendothelial space is the paracellular route. Gaps between endothelial cells are regulated by adherens and tight junctions, which restrict and control the trafficking of macromolecules larger than 6 nm. Because the diameter of HDL particles ranges from 8 to 10 nm, their entrance into the intima of the vessels should be actively regulated. Potent mediators of endothelial permeability such as thrombin, via the protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR1), and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) may represent important modulators of lipoprotein passage into the subendothelial space (Mehta and Malik, 2006; von Eckardstein and Rohrer, 2009). To our knowledge, the paracellular transport of HDLs has not been investigated.

Can HDLs be used for vectorization towards the endothelium?

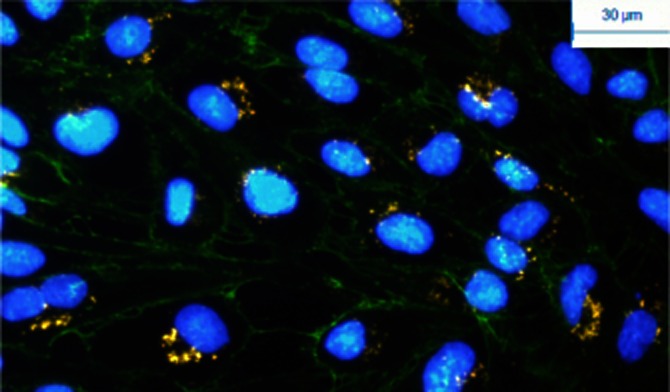

To better understand the mechanism by which HDLs act in endothelial cells beyond RCT, the question of their potential capacity to vectorize protective molecules and/or drugs within the cells should be raised. In smooth muscle cells, HDL uptake was shown to be accompanied by alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) internalization (Ortiz-Munoz et al., 2009). HDL uptake has been documented in different cultures of endothelial cells (Chao et al., 2003; Rohrer et al., 2009), including human microvascular cerebral endothelial cells constituting the BBB (see Figure 2). The BBB provides the brain with nutrients but prevents the introduction of harmful blood-borne substances and restricts the movement of ions and fluid to ensure an optimal environment for brain function. As a consequence of its barrier properties, the BBB also prevents the movement of drugs from the bloodstream into the brain, and therefore acts as an obstacle for the systemic delivery of neurotherapeutic agents. Lapergue et al. (2010) studied the protective effect of intravenous injection of HDLs in a rat model of embolic cerebral ischaemia and showed that HDLs labelled with carbocyanines penetrated the infarct area and colocalized with endothelial cells and also reached the cerebral compartment where they were taken up by astrocytes. Moreover, Kratzer et al. (2007) showed that coating protamine-oligonucleotide nanoparticles with apoA-I enhanced their uptake and increased their transcytosis in cultures of primary porcine brain capillary endothelial cells. Thus, as endothelial cells express receptors for apoA-I, both HDL particles and apoA-I-coated nanoparticles could be used to improve the delivery of drugs across the BBB.

Figure 2.

Internalization of HDLs labelled with DiIC18 carbocyanines (red) in HCMEC/D3 cells (immortalized human brain endothelial cells). Nuclei are labelled with DAPI (diaminophenylindole) and vascular endothelial-cadherins are immunostained in green. Labelled HDLs were incubated with endothelial cells and rapidly taken up (visible after 15 min of contact). After 4 h of incubation, HDL particles concentrate in the perinuclear area (as shown here).

HDLs in pathological conditions

Endothelial dysfunction

Endothelial dysfunction is common to all cardiovascular diseases. It contributes to the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic vascular disease by promoting the recruitment of leukocytes and thrombosis and by impairing the regulation of arterial tone and flow. Numerous cardiovascular risk factors and disorders have been shown to be associated with altered endothelium-dependent relaxation, such as diabetes mellitus, smoking, hypertension, atherosclerosis and heart failure (Widlansky et al., 2003). The endothelial vasomotor tone integrates several factors, such as NO, prostaglandins, endothelin or endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor.

The evaluation of endothelial functionality in humans is often restricted to the measurement of NO-dependent endothelial vascular tone. Clinical studies usually evaluate endothelial vasomotor tone by monitoring changes in flow after stimulation of NO release by the endothelium in response to ACh. ACh has a vasodilatory effect after binding to muscarinic receptors that activate endothelial NO synthase (eNOS). NO, which is produced by eNOS from L-arginine, stimulates the cytosolic guanylate cyclase and increases cGMP content in vascular smooth muscle cells, resulting in relaxation of vascular tone. The most commonly used method to assess endothelium-dependent relaxation is to infuse ACh in the brachial artery and to determine the increase in blood flow in the forearm by venous occlusion plethysmography (Benjamin et al., 1995). Endothelial functionality measured by flow-mediated dilation (FMD) of the brachial artery is impaired in hypercholesterolemic patients, but the underlying mechanisms remain to be elucidated. Several possibilities have been suggested including: (i) a reduced synthesis of NO; (ii) altered membrane receptor coupling mechanisms affecting the release of NO; and (iii) impaired diffusion or augmented destruction of NO in the vessel wall. Spieker et al. (2002) showed that endothelium-dependant vasodilation in response to ACh was reduced in healthy hypercholesterolemic patients compared with normocholesterolemic subjects, although endothelium-independent vasodilation to sodium nitroprusside (SNP) was not altered, which suggested an important role for NO. When hypercholesterolemic patients received an intravenous perfusion of rHDL (at 80 mg kg−1 for 4 h), the endothelium-dependent vasodilation to ACh was significantly enhanced (P = 0.017), whereas endothelium-independent vasodilation to SNP was not altered. The authors concluded that increasing HDL plasma levels may normalize impaired endothelial function in hypercholesterolemic patients. In patients with Tangier disease, who have defective ABCA1 transporters resulting in low circulating HDL levels, impaired NO-dependent FMD was also observed. Intravenous infusion of apoA-I/phosphatidylcholine (PC) in these patients completely restored the vasomotor response, indicating that HDLs play an important role in the maintenance of endothelial function by stimulating NO bioactivity (Bisoendial et al., 2003).

HDLs and eNOS

HDLs are known to promote production of NO and subsequent vasorelaxation (Yuhanna et al., 2001) by different mechanisms:

By maintaining the lipid microenvironment (Uittenbogaard et al., 2000), as HDLs serve as cholesterol donors for caveolae and thus inhibit subcellular redistribution and inactivation of eNOS, and in particular that induced by oxidized LDL (oxLDL). This process was reported to be SR-BI-dependent in human microvascular cerebral endothelial cells

By inducing signalling cascades leading to eNOS phosphorylation, for example, via Akt/MAPK/ERK (Mineo et al., 2003) and AMP-activated protein kinase (Kimura et al., 2010)

By increasing the half-life and thus the abundance of eNOS (Ramet et al., 2003).

Activation of eNOS by statins was shown to involve SR-BI signalling, independently of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibition (Datar et al., 2010), suggesting that this pathway could be involved in HDL-mediated NO production by endothelial cells, as previously described by Yuhanna et al. (2001). SR-BI-blocking antibodies inhibited activation of eNOS by HDLs and HDL signalling was shown to require cholesterol binding and efflux to induce eNOS activation (Yancey et al., 2000; Assanasen et al., 2005). In addition, cyclodextrin (Assanasen et al., 2005) and PC-enriched HDL yielded increased eNOS activation (Yancey et al., 2000), suggesting that cholesterol efflux plays a central role in eNOS stimulation by HDL.

The dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase/asymmetric dimethylarginine (DDAH/ADMA) system is a recently described pathway for modulating NO production (Fiedler, 2008). HDL prevented the decrease in NO production by HUVECs in response to oxLDL, as well as the reduction of DDAH expression and activity, and increased the level of ADMA (Peng et al., 2011).

In vivo, rats pretreated with rHDL had less ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation in a model of ischaemia/reperfusion induced by left coronary artery occlusion. The authors suggested that these beneficial effects of HDLs are mediated by an increased NO production via ABCA1 or ABCG1 and subsequent kinase signalling (Akt/ERK) leading to NOS phosphorylation (Imaizumi et al., 2008).

Similarly, in an in vivo mouse model of myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion, HDL decreased infarction size. HDL and S1P were shown to mediate cardioprotection in an NO-dependent manner and via the S1P3 receptor (Theilmeier et al., 2006).

HDLs and S1P

S1P is the product of sphingosine phosphorylation by sphingosine kinase and can also be released from ceramide. S1P binds to S1P receptors (S1P1–5), which can couple to different G-proteins and drive a multiplicity of intracellular signalling cascades leading to a variety of cellular responses. In endothelial cells, S1P1 appears to be the most highly expressed receptor for S1P, followed by S1P2 and S1P3 receptors (Lucke and Levkau, 2010). S1P1 receptor expression is up-regulated in endothelial cells by thrombin (Takeya et al., 2003) and by hypoxic conditions, suggesting a role of S1P signalling in cerebrovascular diseases (Hayashi et al., 2003). In cultures of human brain endothelial cells, a model of the BBB, S1P5 receptors were important contributors to the maintenance of brain endothelial barrier function via stabilization of adherens junctions (van Doorn et al., 2012).

S1P promotes endothelial barrier function in cultured pulmonary endothelial cells (Garcia et al., 2001) possibly by enhancing tight junction formation (as shown in HUVECs; Lee et al., 2006) and cortical actin assembly (Garcia et al., 2001), resulting in a decreased permeability. Whereas activation of S1P1 and S1P3 receptors enhanced the formation of endothelial junctions, activation of S1P2 receptors appeared to have the opposite effect (Lucke and Levkau, 2010). S1P is also known to stimulate NO production by endothelial cells via eNOS activation (Dantas et al., 2003; Levkau, 2008). Finally, albeit a matter of controversy, S1P is reported to inhibit endothelial activation by TNF-α both in vitro and in vivo. In particular, S1P reduced expression of platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1, E-selectin, vascular endothelial-cadherin, IL-8, and CCL2 (MCP-1), leading to decreased adhesion of leukocytes to TNF-α-activated endothelial cells (Bolick et al., 2005; Krump-Konvalinkova et al., 2005; Whetzel et al., 2006).

HDLs represent the principal acceptor and carrier of S1P, as about 60% of S1P contained in plasma is transported by HDL particles (Karliner, 2013). S1P is preferentially carried by small HDL3 versus large HDL2 (Kontush et al., 2007). Only small amounts of S1P are found in LDL and the quantity decreased upon oxidation. Furthermore, under pathological conditions such as coronary artery disease, S1P associated with HDL was lower than in controls (Sattler et al., 2010). HDL-associated S1P was also reported to promote endothelial motility, a process of potential importance in the case of vascular injury, via Gi-coupled S1P receptors and the Akt signalling pathway (shown in HUVECs; Argraves et al., 2008). In addition, S1P was identified as one of the principal bioactive lysophospholipids in HDLs which is responsible for about 60% of the vasodilatory effect of HDL in isolated aortae ex vivo (Nofer et al., 2004).

S1P was recently reported to specifically bind to apolipoprotein M (apoM), chiefly contained in HDLs and to a lesser extent in LDL (Christoffersen et al., 2006). apoM is a 25 kDa protein predominantly associated with HDL via a retained hydrophobic signal peptide (Christoffersen et al., 2008). About 90% of apoM is contained in HDL, mainly in the α-particles and apoM was recently reported to mediate the S1P vasculoprotective effects of HDL by delivering S1P to the S1P1 receptor (Christoffersen et al., 2011).

Whereas non-HDL-bound S1P can stimulate S1P1-3 receptors, HDL-associated S1P may preferentially be directed to S1P1 receptors through its binding to apoM. S1P may therefore participate in the vasculoprotective effects of HDL including:

NO-dependent modulation of vascular tone

Improved maintenance of low permeability in endothelial cell layers

Decreased leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells

In vivo, administration of human plasma HDLs to mice was shown to stimulate myocardial perfusion (Levkau et al., 2004). The same group published, in a mouse model of cardiac ischaemia/reperfusion, that both S1P and HDLs isolated from plasma reduced the infarct area. This was associated with a reduced leukocyte adhesion to mouse TNF-α-activated endothelial cells (in vitro and under flow) and limited recruitment of neutrophils in the infarct area (Theilmeier et al., 2006).

In atherosclerosis, S1P may be released by activated platelets during intraplaque haemorrhage and clot formation, and then induce both angiogenesis and smooth muscle cell differentiation and proliferation (English et al., 2000; Lockman et al., 2004). The presence of intraplaque neovessels is thought to promote plaque vulnerability (Le Dall et al., 2010); S1P buffering by HDLs could thus limit the progression of atherothrombotic plaques towards rupture.

HDLs limit endothelial procoagulant activity

Tissue factor (TF) is an important initiator of the coagulation cascade. Its expression by endothelial cells is induced by thrombin and may represent a trigger for the acute coronary syndrome. rHDLs were shown to down-regulate TF expression induced by thrombin in HUVECs via inhibition of small G-protein RhoA (Viswambharan et al., 2004). Thrombin also induces CCL2 expression by endothelial (HMEC-1 cell line) and smooth muscle cells that is inhibited by plasma HDLs (Tolle et al., 2008). By inhibiting apoptosis of endothelial cells (see the following paragraph), HDLs could limit the pro-thrombotic phenotype of endothelial cells that undergo apoptosis. A few hours after induction of apoptosis by staurosporin or by serum deprivation, HUVECs became pro-adhesive for non-activated platelets (Bombeli et al., 1999).

Human plasma HDLs were also reported to enhance the anti-aggregating activity of BAECs in an NO-dependent manner (Chen et al., 2000a). PGI2 is a potent inhibitor of leukocyte activation/adhesion and platelet aggregation. rHDLs were shown to enhance TNF-α- and IL-1β-mediated PGI2 production, and thereby to protect against thrombotic complications (Cockerill et al., 1999). HDLs may also affect thrombosis independently of their endothelial effects, by modulating platelet activation, as shown in vivo by injection of rHDL in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and in vitro, in platelets isolated from both control subjects and diabetic patients (Calkin et al., 2009).

HDLs reduce expression of endothelial adhesion molecules in ‘inflammatory conditions’

HDLs were shown to inhibit TNF-α-induced expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and E-selectin by HUVECs, and this effect was reproduced for ICAM-1 by rHDLs. However, HDLs did not inhibit ICAM-1 in fibroblasts stimulated by TNF-α (Cockerill et al., 1995). Stimulation of endothelial cells by TNF-α or IL-1 and subsequent evaluation of VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and E-selectin expression is a commonly used assay for testing the so-called ‘anti-inflammatory effect’ of HDLs. rHDLs were reported to inhibit markedly neutrophil adhesion to endothelial cells in vitro after stimulation by LPS, via a decreased expression of E-selectin and ICAM-1. This effect was much lower when endothelial cells were stimulated by TNF-α. The authors suggested that rHDL blocked LPS activity and modulated CD11b/CD18 up-regulation on neutrophils (Moudry et al., 1997). In the case of Gram-negative endotoxic shock, endothelial cells are the first to be exposed to LPS. HDLs may thus represent an important modulator of the endothelial response to LPS, in addition to their inhibitory effect on circulating neutrophils. Indeed, interaction of LPS with HDL was reported a long time ago (Freudenberg et al., 1980) and LPS was shown to increase HDL clearance through bile and urine (Konig et al., 1988). HDLs isolated from plasma, but not rHDLs, neutralized LPS, unless recombinant LPS binding protein (LBP) was added, suggesting that LBP was necessary to transfer LPS to HDLs (Wurfel et al., 1994). Studies using SR-BI deficient mice also lend support to the role of HDL in LPS clearance as these mice are more susceptible to LPS-induced death (Li et al., 2006) and display decreased plasma clearance of LPS by the liver. In hepatocytes, SR-BI mediated LPS uptake more efficiently when associated with HDLs (Li et al., 2006).

The modulatory effect of HDL on the expression of molecules supporting adhesion of leukocytes has also been reported in vivo, in various models of inflammation. In a porcine model using intradermal injections of IL-1α, rHDLs reduced the expression of E-selectin. This was confirmed in vitro using porcine aortic endothelial cells (Cockerill et al., 2001a). The same author showed in a rat model of hemorrhagic shock that both plasma-derived and rHDLs limited the multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (Cockerill et al., 2001b). In vitro, HDLs prevented neutrophil transmigration across a HUVEC monolayer after stimulation by TNF-α.

The modulatory effects of HDLs on neutrophil activation may also account for their reduced adherence to endothelial cells and subsequent diapedesis. In a mouse model of inflammation induced by intraperitoneal injection of TNF-α, intravenous apoA-I infusion was shown to reduce leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells. rHDLs inhibited CD11b expression by neutrophils both in vitro, in response to PMA, and in human subjects with peripheral vascular disease (Murphy et al., 2011). Modulation of leukocyte activation, including monocytes, by HDLs is thought to be mediated by apoA-I (Murphy et al., 2008). Thus, in combination with decreased expression of adhesion molecules by endothelial cells, HDLs may also limit transmigration of leukocytes and subsequent tissue damage.

In a rabbit model of local inflammation induced by a carotid periarterial collar, Nicholls et al. (2005) showed that infusion of rHDLs and apoA-I reduced neutrophil infiltration and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in the vascular wall. Expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1 and CCL2 by endothelial cells was also inhibited by both rHDLs and apoA-I. In the same model, the 5A apoA-I mimetic peptide (32AA) combined with phospholipids was sufficient to provide these beneficial effects and thus reduced infiltration of circulating neutrophils into the carotid wall (Tabet et al., 2010).

In order to provide mechanistic insights into the anti-inflammatory effects of rHDL on human coronary artery endothelial cells, the same group used a transcriptomic approach to highlight 3β-hydroxysteroid-δ24 reductase (DHCR24) as being up-regulated in HDL-treated cells. rHDLs increased DHCR24 mRNA levels eightfold and protein levels twofold. Plasma HDLs, but not apoA-I, had similar effects. Silencing DHCR24 expression increased NF-κB expression and VCAM-1 in response to TNF-α, relative to untreated cells (McGrath et al., 2009). DHCR24, known to convert desmosterol into cholesterol (Waterham et al., 2001), is also reported to be anti-apoptotic and a potent scavenger of hydrogen peroxide (Lu et al., 2008).

Antioxidant properties of HDLs

The antioxidant capacity of HDLs is reported to be mainly associated with small dense HDL subfractions and is principally conferred by the presence of apolipoproteins and enzymes transported by HDLs including paraoxonase (PON), platelet-activating factor-acetyl hydrolase (PAF-AH), lecithin-cholesterol acyl transferase and glutathione peroxidase (Kontush and Chapman, 2010; Podrez, 2010; Tabet and Rye, 2009).

Endothelial injury and activation induce a substantial penetration and retention of LDL particles in the subendothelial space where they are oxidized by ROS-producing systems, such as the mitochondrial electron chain transport, NADPH oxidase and uncoupled endothelial NO synthase, in resident and infiltrating cells (Parthasarathy and Santanam, 1994; Mabile et al., 1997). Then, oxLDLs can interact with endothelial cells and other vascular cells to produce a variety of responses (Parthasarathy et al., 1999).

HDLs inhibit LDL oxidation

The most well-documented antioxidant effect of HDLs is their ability to inhibit LDL oxidation. The mechanism involved in oxLDL detoxification can be separated into two consecutive steps: (i) the transfer of oxidized lipids from oxLDL, such as lipid hydroperoxides and lysophosphatidylcholine, to HDL particles. This exchange occurs directly via the interaction of LDL with HDL particles or is mediated by the cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) (Christison et al., 1995); and (ii) inactivation of oxidized lipids. The reduction of lipid hydroperoxides in their inactive hydroxide form primarily involves the methionine residues 118 and 145 of apoA-I (Garner et al., 1998).

Other HDL-associated enzymes also participate in hydrolysis of oxidized lipids. PONs hydrolyse lipid peroxides by the interaction of a free sulfhydryl group with oxidized phospholipids, as shown for PON-1 (Aviram et al., 1999). PAF-AH also hydrolyses oxidized phospholipids more efficiently than PON-1 (Marathe et al., 2003). Glutathione peroxidase, a well-known antioxidant enzyme, is also involved in oxLDL detoxification (Arthur, 2000). Compatible with these mechanisms, HDLs are the major carrier of F-2 isoprostanes, a stable product of lipid peroxidation (Proudfoot et al., 2009).

Another mechanism by which HDL inhibits oxidation is the decrease in ROS production by the inactivation of neutrophil NADPH oxidase (Kopprasch et al., 2004; Liao et al., 2005).

Finally, lipophilic antioxidants such as vitamin E and carotenoids are transported by HDL and represent a small contribution to the antioxidant properties of HDL (Goulinet and Chapman, 1997). HDLs have been reported to promote the uptake of α-tocopherol (the most active member of the vitamin E family) by cerebral endothelial cells (Goti et al., 2000), and this action was mediated by SR-BI (Goti et al., 2001).

HDLs inhibit intracellular oxidative stress in endothelial cells

HDLs counteract intracellular oxidative stress induced by a variety of stimuli, including oxLDL, acute phase proteins, etc. For example, HDLs were reported to decrease superoxide anion production observed in endothelial cells in response to oxLDL in HUVECs and BAECs (Suc et al., 1997; Lee et al., 2005) or to serum amyloid A (SAA) protein in HAECs (Witting et al., 2011).

In HAECs, HDLs were shown to reduce the intracellular oxidative stress induced by 7-ketocholesterol in an ABCG1-dependent manner. These authors also showed in vivo, in mice fed with a high-fat diet, that 7-ketocholesterol levels were increased in endothelial cells of ABCG1−/− mice, relative to those of wild-type mice (Terasaka et al., 2008).

Oxidized/modified HDLs have reduced protective effects

It should be noted that oxidative modifications of HDLs participate in the impairment of HDL functionality. HDLs exposed to peroxynitrite increased their 3-nitrotyrosine levels. These oxidatively modified HDLs reduced HAEC viability associated with decreased expression of Cu2+, Zn2+ superoxide dismutase (Matsunaga et al., 2001).

In particular, HDLs isolated from atherosclerotic lesions and from plasma of patients with coronary artery disease presented modifications specific to myeloperoxidase (MPO) (Pennathur et al., 2004). In pathological conditions, MPO can bind HDLs and induce oxidative modifications on these particles (Bergt et al., 2004; Shao et al., 2012). It is now well documented that apoA-I represents the principal target for HOCl and that chlorinated apoA-I compromises the major function of HDL cholesterol efflux but also favours endothelial activation via NF-κB-mediated adhesion molecule expression (Zheng et al., 2004; Undurti et al., 2009; Shao et al., 2012). Also, MPO can bind to the endothelium and decrease vascular NO bioavailability (Baldus et al., 2001). Heparin was suggested to mobilize vessel-bound MPO and thus improve endothelial function (Rudolph et al., 2010). If HDL could, in a similar way, increase MPO clearance, this could also contribute to the beneficial effects of HDLs on endothelial function in vivo.

Reduced antioxidant capacity of HDLs in pathological conditions

HDLs isolated from patients with coronary artery disease were shown to have a reduced potential to activate eNOS. This was in part explained by a reduced HDL-associated PON1 activity, leading to increased formation of malondialdehyde in HDL particles and subsequent activation of the LOX-1 signalling pathway leading to inhibition of eNOS activation by these HDLs (Besler et al., 2011).

Antioxidant capacity of HDLs, determined by their inhibitory potential on copper-induced LDL oxidation, was decreased in patients with essential hypertension. Carotid artery intima-media thickness was negatively correlated with HDL antioxidant activity (Chen et al., 2010).

In women with primary antiphospholipid syndrome, the beneficial effects of HDLs: endothelial NO production, reduction of superoxide anion production and monocyte adhesion to HAECs in response to TNF-α, were blunted relative to those from controls (Charakida et al., 2009). In coronary artery disease, patients display impaired endothelial function (Esper et al., 1999), and an unsuccessful attempt has been made to remedy this by injection of rHDLs (Chenevard et al., 2012). A recent proteomic study reported differential protein profiles in HDLs isolated by ultracentrifugation between stable coronary artery disease, acute coronary syndrome and controls. Decreased abundance of apoA-IV, suggested to be antioxidant (Ostos et al., 2001), was demonstrated in patients with stable and acute coronary artery disease, relative to controls (Alwaili et al., 2012). It was recently reported that the antioxidant capacity of apoB-depleted serum (considered as ‘HDL’ by the authors) was blunted in patients with acute coronary syndrome compared with controls or patients with stable coronary artery disease (Patel et al., 2011).

The link between the antioxidant properties and the protein and lipid cargo of HDLs should be investigated in more detail in order to assess its impact on endothelial function.

Endothelial protection by HDL: does size matter?

The capacity of the different subclasses of HDLs to promote cholesterol efflux depends principally on the cellular receptors involved in this process. Small pre-β HDL particles correlate significantly with ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux (Asztalos et al., 2005), whereas larger HDL particles preferentially bind to SR-BI, allowing selective uptake of cholesterol esters (de Beer et al., 2001). Concerning the antioxidant activity, Kontush et al. (2003) showed that the protection of LDL against oxidation increased with the density of HDL subfractions (HDL2b < HDL2a < HDL3a < HDL3b < HDL3c). In particular, PON-1 activity was shown to be predominant in the HDL3 fraction (Bergmeier et al., 2004). Small, dense, lipid-poor HDL3 particles also display cytoprotective effects in a model of endothelial cell apoptosis induced by oxLDLs, via inhibition of intracellular ROS generation (de Souza et al., 2010). Moreover, small dense HDL particles exert a higher ‘anti-inflammatory activity’ than large HDL particles: HDL3 was shown to inhibit VCAM1 expression in cytokine-activated HUVECS more efficiently than HDL2 (Ashby et al., 1998). On the other hand, large HDL2 particles were shown to more strongly inhibit platelet aggregability than small dense HDL3 (Desai et al., 1989). In pathological situations such as cardiovascular disease, reduced levels of HDL2 particles could be more strongly predictive of cardiovascular disease risk than are concentrations of HDL3 (Krauss, 2010). However, because several different techniques are used to assess HDL size, as well as the protein and lipid cargo carried by HDL particles, correlations of size with function should be treated with caution.

HDLs prevent apoptosis of endothelial cells

HDLs have been shown to inhibit apoptosis of endothelial cells induced by different stimuli such as oxLDL and TNF-α (Suc et al., 1997; Sugano et al., 2000). Importantly, both the death receptor (TNF-α) and the mitochondrial apoptotic pathways can be inhibited by HDLs. In oxLDL-induced apoptosis, it was nicely shown that HDLs interfere with endoplasmic reticulum and the autophagic response of human microvascular endothelial cells stimulated by mildly oxLDLs (by UV-C irradiation) (Muller et al., 2011a,b). In this model, HDLs inhibited intracellular ROS generation and the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway (i.e. cytochrome C release into the cytosol), but also caspase-independent apoptotic pathways mediated by the apoptosis-inducing factor (de Souza et al., 2010).

Nofer et al. (2001) used growth factor deprivation for induction of apoptosis in HUVECs to show that HDL prevented mitochondrial changes, caspase 9 and 3 activation and stimulated Akt, an important anti-apoptotic pathway (Nofer et al., 2001). Whereas this group attributed the anti-apoptotic effects of HDLs to sphingolipids, de Souza et al. (2010) showed that apoA-I was mainly responsible for the protection against apoptosis in their model. HDLs may therefore display anti-apoptotic effects associated with both their lipid and their protein moieties, depending on the apoptotic trigger.

HDLs and the BBB

The BBB is composed of specialized endothelial cells with a particularly dense network of tight junctions, pericytes and astrocyte endfeet. It represents an active interface between the blood stream and the CNS and endothelial cells play a central role in the control of transcellular and paracellular transport of nutrients and the removal of metabolites (Wilhelm et al., 2011). BBB endothelial cells represent the first cell type to be affected in pathological situations such as ischaemia, for example. Cerebral ischaemia leads to BBB degradation which increases its permeability and subsequently to a loss of brain homeostasis.

The action of neutrophils on the permeability of the BBB remains unclear. Inglis et al. (2004) reported that, under non-stimulated conditions, neutrophil-endothelial cell interactions led to a decreased permeability whereas fMLP-activated neutrophils led to increased permeability, associated with transmigration through the endothelium. This process was dependent on intracellular calcium in endothelial cells and also partially on serine proteases, as it was inhibited by aprotinin. In vivo, IL-1β was reported to induce neutrophil adhesion and migration associated with an increased permeability of the BBB and a disorganization of the junction proteins (occludin, ZO-1, etc.) (Bolton et al., 1998). Interestingly, the transendothelial migration of neutrophils following stimulation of the BBB by TNF-α was accompanied by an increased permeability but, after the migration period, the endothelial layer regained its low permeability (Wong et al., 2007). This suggests that activation of endothelial cells is sufficient for expression of adhesion molecules and recruitment of neutrophils, but permanent BBB disruption may require additional factors, such as PMN activation.

Elastase, which is a major protease released by activated neutrophils, has been suggested to be an important mediator of endothelial layer permeability (Killackey and Killackey, 1990; Suttorp et al., 1993; Carl et al., 1996). For this reason, the recently reported anti-elastase activity of HDLs (Ortiz-Munoz et al., 2009) may represent a novel protective effect of these particles in pathological conditions, involving neutrophil activation and subsequent elastase release. In particular, HDLs may be able to transport α-antitrypsin (AAT) into the cells where it could thwart the deleterious effects of intracellular elastase (Houghton et al., 2010). AAT was shown to inhibit caspase 3 activity and thus prevent pulmonary EC apoptosis (Petrache et al., 2006).

ROS increase the permeability of the BBB in both in vivo and in vitro models (Kahles et al., 2007). For example, superoxide dismutase-deficient mice exhibit high levels of superoxide anion associated with increased permeability of the BBB following ischaemia/reperfusion (Kondo et al., 1997). Under hyperglycaemic conditions, oxidative stress and matrix metalloproteinase-9 were implicated in BBB dysfunction after ischaemia/reperfusion in a model of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats (Kamada et al., 2007). Because HDLs display antioxidant effects (Barter et al., 2004) and rHDLs were shown to restore endothelial function in hyperglycaemic conditions (Nieuwdorp et al., 2008), it is possible that they may have beneficial effects on BBB in these pathological conditions.

HDLs and endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs)

HDLs were shown long ago to promote proliferation in BAECs (Tauber et al., 1980). EPCs are circulating cells derived from the bone marrow involved in the natural turnover of endothelial cells as well as in vascular repair in different pathological situations (Fadini et al., 2007). They were first isolated from mononuclear blood cells based on their CD34 expression (Asahara et al., 1997). The number of EPCs was reported to be correlated with HDL cholesterol levels in young adult healthy subjects (Dei Cas et al., 2011). In addition, in hypercholesterolemic patients, HDL cholesterol was found to be a strong determinant of both EPC number and function. Indeed, decreased EPC number was associated with low HDL and endothelial dysfunction (impaired endothelial-dependent vasodilatation) (Rossi et al., 2010). In vitro, HDLs were able to promote rat EPC proliferation, migration and tube formation via activation of PI3K/Akt intracellular signalling. In hypercholesterolemic rats, intravenous injection of human plasma HDLs increased circulating EPC number and promoted re-endothelialization in wound healing (Zhang et al., 2010). Using a model of transplant arteriosclerosis, the group of De Geest elegantly demonstrated that adenoviral human apoA-I transfer increased both HDL levels and the number of circulating EPCs, and limited neointima formation. This was accompanied by an enhanced incorporation of EPCs into allografts and improved endothelial regeneration (Feng et al., 2008). Furthermore, increased number and function of EPCs induced by apoA-I transfer was dependent on SRB-I expression in the bone marrow (Feng et al., 2009). Finally, the same group recently reported that topical HDL administration to the adventitia limited vein graft atherosclerosis associated with increased incorporation of EPCs and improved endothelial regeneration (Feng et al., 2011).

In a mouse model of endothelial injury in response to LPS, intravenous injection of rHDLs increased circulating EPC number (Tso et al., 2006). In a mouse model of hindlimb ischaemia, rHDL promoted EPC differentiation from mononuclear cells as well as increasing their angiogenic capacity (Sumi et al., 2007). Moreover, HDLs, in vitro, inhibited apoptosis of EPCs, thus increasing their proliferation and subsequent formation of outgrowth colonies and promoting their capacity to adhere to endothelial cells. Finally, in vivo, injection of rHDLs enhanced re-endothelialization after denudation in mice (Petoumenos et al., 2009). In a model of vein graft to carotid arteries (in apoE deficient mice), topical application of HDLs significantly reduced the intimal area and potently enhanced endothelial regeneration. These effects of HDLs were suggested to be related to increased incorporation of circulating progenitor cells (Feng et al., 2011). In vitro, a recent study has reported that high concentrations of HDLs enhanced EPC senescence and impaired tube formation (Huang et al., 2012).

In humans, infusion of rHDLs was attempted in patients with type 2 diabetes and led to an increase in circulating EPCs that was significant at day 7 post-injection (van Oostrom et al., 2007). In their study, Petoumenos et al. (2009) also reported a correlation between circulating EPC number and HDL concentration in patients with coronary artery disease. Taken together, the beneficial effects of apoA-I, HDL and rHDLs on EPC number and function could be one explanation for the vasculoprotective actions of HDLs in pathological conditions.

HDLs and endothelial dysfunction in diabetes

Diabetes represents a good example of a pathological condition that integrates different aspects of the relationship between HDLs and endothelial cells. Endothelial dysfunction is a hallmark of diabetes; it has been linked to type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance in experimental and clinical studies (Creager et al., 2003). Various mechanisms leading to endothelial dysfunction in diabetes have been suggested: (i) an altered cell signalling in endothelial cells that results in an impaired ability to produce NO in response to physiological stimuli; (ii) an increased oxidative stress in the vasculature; and (iii) a pro-inflammatory activation of endothelial cells. Nieuwdorp et al. (2008) showed in type 2 diabetics that the forearm blood flow (FBF) response to serotonin was decreased relative to non-diabetic subjects. Four hours after infusion of rHDL (80 mg kg−1) in diabetic patients, the FBF response to serotonin was significantly restored. On the contrary, in controls, rHDL infusion had no effect on serotonin-induced vasodilation. Interestingly, there was still a trend toward improved NO availability 7 days after rHDL infusion, when apoA-I plasma levels had returned to baseline.

Diabetes is also characterized by increased oxidative stress, in particular in dysfunctional endothelial cells (Tesfamariam, 1994). Non-enzymic glycosylation and oxidation of HDLs is thought to occur in diabetic patients. These modified HDLs induce H2O2 production by HAECs and were shown to reduce eNOS expression associated with decreased NO production (Matsunaga et al., 2003). Human apoA-I gene transfer in a rat model of diabetes induced by streptozotocin was shown to thwart induction of aortic angiotensin AT1 receptor expression. In vivo, NADPH activity was reduced, whereas eNOS dimerization and subsequent NO bioavailability were increased. In vitro, inhibition of hyperglycaemia-induced AT1 receptor up-regulation by HDLs in HAECs was paralleled by decreased NADPH activity and ROS production. In experimental diabetic conditions, the vasculo-protective effects of HDLs could thus be mediated by the down-regulation of AT1 receptors (Van Linthout et al., 2009).

HDLs from patients with type 2 diabetes have been extensively characterized for their capacity to modulate endothelium-dependent vasodilation and EPC-mediated repair in a model of carotid injury in nude mice (Sorrentino et al., 2010). Both HDLs and EPCs from diabetic patients were shown to be dysfunctional. HDLs exhibited increased lipid peroxidation and MPO activity relative to controls, and displayed a reduced capacity to induce endothelial NO production. Furthermore, EPC number and function were reported to be altered in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes (Tepper et al., 2002; Loomans et al., 2004), and EPC count was lower in healthy hyperinsulinemic men (Dei Cas et al., 2011).

HDL3 particles isolated from type 2 diabetics displayed an altered antioxidative activity relative to controls (Nobecourt et al., 2005). Because increased generation of ROS is closely associated with endothelial dysfunction in this disease (Cai and Harrison, 2000), less effective HDLs in the prevention of oxidative stress could participate in this process. Finally, HDLs isolated from patients with type 2 diabetes exhibited an increased «inflammatory index», defined as the ability of HDLs to interfere with LDL-induced monocyte chemotactic activity. HAECs were incubated with LDL ± HDL for 16 h and the resulting conditioned medium was used to attract monocytes in a Transwell system (Morgantini et al., 2011). In conclusion, modified HDLs in diabetic patients may reflect and/or participate in endothelial dysfunction that could be reversed by infusion of rHDLs (see paragraph on HDLs and Proteomics and Table 1). Furthermore, infusion of rHDL was also shown to modulate glucose metabolism by increasing plasma insulin levels (Drew et al., 2009), in particular by modulation of beta cell function (Fryirs et al., 2010; Kruit et al., 2010).

Table 1.

Use of HDL therapy in vivo

| HDL type | Model | Species | Endothelial end-point | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pHDL | Stroke | Rat | BBB permeability | (Lapergue et al., 2010) |

| rHDL | Stroke | Rat | Generation of ROS | (Paterno et al., 2004) |

| rHDL | Diabetes (type 2) | Human | Vasodilation | (Nieuwdorp et al., 2008) |

| apoA-I mimetic | Diabetes (type 1) | Rat | Endothelial cell sloughing | (Kruger et al., 2005) |

| Endothelial cell fragmentation | ||||

| Vasodilation | ||||

| rHDL | Atherosclerosis | Human | VCAM-1 expression | (Shaw et al., 2008) |

| apoA-I mimetic | Hypercholesterolemia | Mouse | Vasodilation | (Ou et al., 2003) |

| Sickle cell disease | ||||

| rHDL | Hypercholesterolemia | Human | Vasodilation | (Spieker et al., 2002) |

| rHDL | ACS | Human | Vasodilation | (Chenevard et al., 2012) |

| pHDL | Cardiac ischaemia/reperfusion | Mouse | Neutrophil infiltration | (Theilmeier et al., 2006) |

| Monocyte adhesion | ||||

| pHDL | S1P3−/− | Mouse | Vasodilation | (Nofer et al., 2004) |

| rHDL | Acute inflammation of carotid artery | Rabbit | Neutrophil infiltration | (Nicholls et al., 2005) |

| Generation of ROS | ||||

| Endothelial inflammation | ||||

| rHDL | Acute inflammation of intradermal vessels | Porcine | Endothelial activation | (Cockerill et al., 2001a) |

| pHDL | Carotid artery electric injury | Mouse | Endothelium regeneration | (Besler et al., 2011) |

| rHDL | Perivascular electric injury | Mouse | Endothelium regeneration | (Seetharam et al., 2006) |

| rHDL | Hypo-α−lipoproteinaemia | Human | Vasodilation | (Bisoendial et al., 2003) |

| apoA-I mimetic | Systemic sclerosis | Mouse | Vasodilation | (Weihrauch et al., 2007) |

| Angiogenic potential | ||||

| rHDL | Vein graft | Mouse | Endothelium regeneration | (Feng et al., 2011) |

| Endothelium inflammation | ||||

| rHDL | Endothelial damage (LPS) | Mouse | Progenitor-mediated endothelial repair | (Tso et al., 2006) |

| pHDL | Endotoxin-induced leukocyte adhesion (LPS) | Rat | Leukocyte adhesion | (Thaveeratitham et al., 2007) |

| rHDL | Endotoxic shock (Escherichia coli) | Rat | Endothelium inflammation | (McDonald et al., 2003) |

| rHDL | Renal ischaemia/reperfusion | Rat | Neutrophil infiltration | (Thiemermann et al., 2003) |

| Endothelium inflammation |

rHDL: reconstituted HDL; pHDL: plasma HDL; apo: apolipoprotein; ACS: acute coronary syndrome; ROS: reactive oxygen species; LPS: lipopolysaccharide; S1P3: sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 3.

HDLs from coronary artery disease patients

HDL isolated from patients with coronary artery disease displayed an impaired endothelial repair capacity in a model of carotid artery injury re-endothelialization performed in nude mice. These effects of HDL were suggested to be dependent on eNOS activation, since they were not observed in eNOS-deficient mice (Besler et al., 2011). In hyperlipemic patients, association studies have shown that HDL – cholesterol concentration was an independent predictor of good endothelial function (Lupattelli et al., 2002) and was inversely correlated with VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 levels (Lupattelli et al., 2003).

HDL-omics and perspectives

A more detailed characterization of HDL particle composition is still necessary in order to better understand their functions and dysfunctions in pathological conditions. Open approaches such as proteomics and lipidomics aimed at identifying and quantifying proteins and lipids associated with HDL particles have been attempted. «Lipoproteomics I and II» published in 2005 reported a list of proteins associated with LDL and HDL fractions isolated by ultracentrifugation (Karlsson et al., 2005a,b). AAT was identified in HDLs for the first time. This anti-elastase protein was confirmed to be associated with HDLs by various techniques and HDLs were shown to inhibit vascular cell apoptosis induced by elastase (Ortiz-Munoz et al., 2009). In addition, HDLs could be enriched in vitro by adding AAT to increase their anti-elastase potential. The identification of new proteins or lipids that can naturally bind to HDL particles suggests that their functionality could be improved and that HDLs could be used as vectors for therapeutic agents in acute or chronic conditions (Burillo and Civeira, 2012a). Other proteomic studies have highlighted proteins associated with HDLs that could affect endothelial cells, in particular proteinase inhibitors, acute phase proteins or those regulating the complement system (Vaisar et al., 2007). Many proteins identified in HDLs could modulate their function or provide them with new properties. For example, what is the biological significance of the presence of growth arrest-specific gene 6 in HDLs, buried in a list of 56 identified proteins (Rezaee et al., 2006)? Is its association with HDLs a means of inactivating this potential pro-inflammatory protein, reported to enhance interactions between endothelial cells, platelets and leukocytes (Tjwa et al., 2008)?

A recent study reported the identification of 122 proteins, by comparing HDLs isolated from control subjects to those from haemodialysis patients (Mange et al., 2012). In view of the increasing sensitivity of proteomic techniques, the number of HDL particles that bind a specific protein should be considered when evaluating whether the protein could impact on HDL function. Also, whether each HDL subfraction has a specific protein and lipid cargo should be considered.

In diabetes, only a few proteomic or lipidomic studies have been reported. HDLs isolated from type 2 diabetics have a different lipid composition (decreased free cholesterol and cholesterol ester levels, increased phospholipids) from that of controls and a different protein profile, in particular in HDL3 subfractions. A decreased cargo of PON-1 and PAF-AH may account for their impaired antioxidant capacity (Nobecourt et al., 2005). It is possible that PON-1 or apoA-I could be replaced under oxidative stress and/or inflammatory conditions (Kontush and Chapman, 2006). For example, oxLDL can modify the ratio of apolipoprotein J (clusterin):PON in HDLs (Navab et al., 1997). A recent proteomic study on HDLs isolated from type 2 diabetic, insulin-sensitive, insulin-resistant, lean or obese patients and controls showed that decreased levels of clusterin in HDLs were associated with insulin resistance, obesity and dyslipoproteinaemia (Hoofnagle et al., 2010). Specific diets may also influence the HDL proteome, as reported following ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplemented-diet that led to increased levels of PON-1 and clusterin associated with HDL particles (Burillo et al., 2012b).

Another recent study in patients with type 2 diabetes assessed the lipidome in HDL fractions and the authors linked their blunted antioxidant capacity to their increased content in oxidized fatty acids. In these patients, plasma levels of serum amyloid A (an acute phase protein) were also increased, reflecting the inflammatory state of these diabetic patients (Morgantini et al., 2011). In a recent proteomic study in patients with stable coronary artery disease or acute coronary syndrome, HDLs were shown to have increased abundance of serum amyloid A and complement C3, reflecting a shift to an «inflammatory» profile that might alter their protective effect, although their RCT capacity was unchanged compared with controls (Alwaili et al., 2012). In vitro, serum amyloid A induced Ca++-dependent superoxide anion generation and reduced NO bioavailability in HAECs. Pre-incubation with HDLs decreased intracellular calcium influx, O2-production and gene expression of NF-κB and TF (Witting et al., 2011). HDLs isolated from coronary artery disease patients were not able to induce anti-apoptotic gene expression or to prevent apoptosis of endothelial cells either in vitro or in vivo, in contrast to HDLs isolated from healthy subjects. HDL proteomic analysis suggested a reduced clusterin and an increased apoC-III content in HDLs from coronary artery disease, compared with healthy subjects (Riwanto et al., 2013).

Modifications of apoA-I and changes in both lipid and protein composition of HDL particles directly affect the function of HDLs. Further investigations combining lipidomic and proteomic studies are needed to understand, and thus to limit, the HDL modifications specific to each pathological condition.

Conclusion

HDLs represent a highly heterogeneous family that have in common their major protein, apoA-I, and a phospholipid layer. HDL particles are dynamic in terms of their protein and lipid cargoes that provide them with various functions including anti-oxidant, anti-protease, anti-inflammatory, anti-thrombotic or anti-apoptotic actions, which account for their global protective effects on the endothelium. Therefore, these particles should not be regarded as ‘molecules’ with a fixed composition (Patel et al., 2011), but as dynamic multi-molecular complexes whose composition varies according to their environment.

In pathological conditions, HDLs may scavenge a variety of noxious molecules such as LPS, acute phase proteins, ROS etc., that directly affect their function. Although RCT remains the best characterized function of HDLs, there is a paucity of information on the mechanisms by which HDL particles reach the sub-endothelial space to exert their anti-atherosclerotic functions. Several studies have used acute HDL therapies in vivo, including in humans, in order to prevent or to limit endothelial dysfunction in various pathologies. Table 1 summarizes the therapeutic use of HDLs, rHDLs, apoA-I or mimetic peptides, in different pathological settings. The use of CETP inhibitors to increase HDL cholesterol levels may not be sufficient to restore all HDL functions, in a pathological context. Infusion of functional HDLs, either reconstituted with appropriate protective molecules in addition to apoA-I and phospholipids or isolated from plasma of healthy subjects, may therefore constitute a promising option, in particular in acute situations such as acute coronary syndrome or stroke. Further investigations are needed to improve the cargo and hence the function of HDLs, by combining protective agents that may be delivered to the endothelial layer.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mary Osborne-Pellegrin for help in editing the manuscript. OM is supported by the Fondation de France, the Fondation Coeur et Artère and the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR JCJC 1105).

Glossary

- AAT

α-1 antitrypsin

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- apoA-I

apolipoprotein A-I

- BAEC

bovine aortic endothelial cell

- BBB

blood brain barrier

- CETP

cholesterol ester transfer protein

- DDAH

dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase

- ADMA

asymmetric dimethylarginine

- DHCR24

3β-hydroxysteroid-Δ24 reductase

- EPC

endothelial progenitor cell

- FBF

forearm blood flow

- FMD

flow-mediated dilation

- HAEC

human aortic endothelial cell

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- LBP

lipopolysaccharide binding protein

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- oxLDL

oxidized low-density lipoprotein

- PAF-AH

platelet-activating factor-acetyl hydrolase

- PAR1

protease-activated receptor 1

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- PON

paraoxonase

- RCT

reverse cholesterol transport

- rHDL

reconstituted high-density lipoprotein

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- S1P

sphingosine-1-phosphate

- SNP

sodium nitroprusside

- SR-BI

scavenger receptor B type I

- TF

tissue factor

- VCAM-1

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

- VVO

vesiculo-vacuolar organelles

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acton SL, Scherer PE, Lodish HF, Krieger M. Expression cloning of SR-BI, a CD36-related class B scavenger receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:21003–21009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aird WC. Phenotypic heterogeneity of the endothelium: I. Structure, function, and mechanisms. Circ Res. 2007a;100:158–173. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000255691.76142.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aird WC. Phenotypic heterogeneity of the endothelium: II. Representative vascular beds. Circ Res. 2007b;100:174–190. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000255690.03436.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alwaili K, Bailey D, Awan Z, Bailey SD, Ruel I, Hafiane A, et al. The HDL proteome in acute coronary syndromes shifts to an inflammatory profile. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821:405–415. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RG. The caveolae membrane system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:199–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa R, Abe-Dohmae S, Asai M, Ito JI, Yokoyama S. Involvement of caveolin-1 in cholesterol enrichment of high density lipoprotein during its assembly by apolipoprotein and THP-1 cells. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:1952–1962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argraves KM, Gazzolo PJ, Groh EM, Wilkerson BA, Matsuura BS, Twal WO, et al. High density lipoprotein-associated sphingosine 1-phosphate promotes endothelial barrier function. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25074–25081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801214200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur JR. The glutathione peroxidases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:1825–1835. doi: 10.1007/PL00000664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, Silver M, van der Zee R, Li T, et al. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science. 1997;275:964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashby DT, Rye KA, Clay MA, Vadas MA, Gamble JR, Barter PJ. Factors influencing the ability of HDL to inhibit expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:1450–1455. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.9.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assanasen C, Mineo C, Seetharam D, Yuhanna IS, Marcel YL, Connelly MA, et al. Cholesterol binding, efflux, and a PDZ-interacting domain of scavenger receptor-BI mediate HDL-initiated signaling. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:969–977. doi: 10.1172/JCI200523858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asztalos BF, de la Llera-Moya M, Dallal GE, Horvath KV, Schaefer EJ, Rothblat GH. Differential effects of HDL subpopulations on cellular ABCA1- and SR-BI-mediated cholesterol efflux. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:2246–2253. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500187-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviram M, Rosenblat M, Billecke S, Erogul J, Sorenson R, Bisgaier CL, et al. Human serum paraoxonase (PON 1) is inactivated by oxidized low density lipoprotein and preserved by antioxidants. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26:892–904. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldus S, Eiserich JP, Mani A, Castro L, Figueroa M, Chumley P, et al. Endothelial transcytosis of myeloperoxidase confers specificity to vascular ECM proteins as targets of tyrosine nitration. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1759–1770. doi: 10.1172/JCI12617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barter PJ, Nicholls S, Rye KA, Anantharamaiah GM, Navab M, Fogelman AM. Antiinflammatory properties of HDL. Circ Res. 2004;95:764–772. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000146094.59640.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Beer MC, Durbin DM, Cai L, Jonas A, de Beer FC, van der Westhuyzen DR. Apolipoprotein A-I conformation markedly influences HDL interaction with scavenger receptor BI. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:309–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin N, Calver A, Collier J, Robinson B, Vallance P, Webb D. Measuring forearm blood flow and interpreting the responses to drugs and mediators. Hypertension. 1995;25:918–923. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.5.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmeier C, Siekmeier R, Gross W. Distribution spectrum of paraoxonase activity in HDL fractions. Clin Chem. 2004;50:2309–2315. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.034439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergt C, Pennathur S, Fu X, Byun J, O'Brien K, McDonald TO, et al. The myeloperoxidase product hypochlorous acid oxidizes HDL in the human artery wall and impairs ABCA1-dependent cholesterol transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13032–13037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405292101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besler C, Heinrich K, Rohrer L, Doerries C, Riwanto M, Shih DM, et al. Mechanisms underlying adverse effects of HDL on eNOS-activating pathways in patients with coronary artery disease. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2693–2708. doi: 10.1172/JCI42946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisoendial RJ, Hovingh GK, Levels JH, Lerch PG, Andresen I, Hayden MR, et al. Restoration of endothelial function by increasing high-density lipoprotein in subjects with isolated low high-density lipoprotein. Circulation. 2003;107:2944–2948. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070934.69310.1A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodzioch M, Orso E, Klucken J, Langmann T, Bottcher A, Diederich W, et al. The gene encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 is mutated in Tangier disease. Nat Genet. 1999;22:347–351. doi: 10.1038/11914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolick DT, Srinivasan S, Kim KW, Hatley ME, Clemens JJ, Whetzel A, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate prevents tumor necrosis factor-{alpha}-mediated monocyte adhesion to aortic endothelium in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:976–981. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000162171.30089.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton SJ, Anthony DC, Perry VH. Loss of the tight junction proteins occludin and zonula occludens-1 from cerebral vascular endothelium during neutrophil-induced blood-brain barrier breakdown in vivo. Neuroscience. 1998;86:1245–1257. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombeli T, Schwartz BR, Harlan JM. Endothelial cells undergoing apoptosis become proadhesive for nonactivated platelets. Blood. 1999;93:3831–3838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Wilson A, Marcil M, Clee SM, Zhang LH, Roomp K, van Dam M, et al. Mutations in ABC1 in Tangier disease and familial high-density lipoprotein deficiency. Nat Genet. 1999;22:336–345. doi: 10.1038/11905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burillo E, Civeira F. HDL proteome: new possibilities in the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2012a;10:391. doi: 10.2174/157016112800812773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burillo E, Mateo-Gallego R, Cenarro A, Fiddyment S, Bea AM, Jorge I, et al. Beneficial effects of omega-3 fatty acids in the proteome of high-density lipoprotein proteome. Lipids Health Dis. 2012b;11:116. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-11-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Harrison DG. Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: the role of oxidant stress. Circ Res. 2000;87:840–844. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.10.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi L, Franceschini G. High density lipoprotein and coronary heart disease: insights from mutations leading to low high density lipoprotein. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1997;8:219–224. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199708000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkin AC, Drew BG, Ono A, Duffy SJ, Gordon MV, Schoenwaelder SM, et al. Reconstituted high-density lipoprotein attenuates platelet function in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus by promoting cholesterol efflux. Circulation. 2009;120:2095–2104. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.870709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo D, Vega MA. Identification, primary structure, and distribution of CLA-1, a novel member of the CD36/LIMPII gene family. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:18929–18935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camont L, Chapman MJ, Kontush A. Biological activities of HDL subpopulations and their relevance to cardiovascular disease. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:594–603. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carl VS, Moore EE, Moore FA, Whalley ET. Involvement of bradykinin B1 and B2 receptors in human PMN elastase release and increase in endothelial cell monolayer permeability. Immunopharmacology. 1996;33:325–329. doi: 10.1016/0162-3109(96)00055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavelier C, Rohrer L, von Eckardstein A. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 modulates apolipoprotein A-I transcytosis through aortic endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2006;99:1060–1066. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250567.17569.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavelier C, Ohnsorg PM, Rohrer L, von Eckardstein A. The beta-chain of cell surface F(0)F(1) ATPase modulates apoA-I and HDL transcytosis through aortic endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:131–139. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.238063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao WT, Fan SS, Chen JK, Yang VC. Visualizing caveolin-1 and HDL in cholesterol-loaded aortic endothelial cells. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:1094–1099. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300033-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charakida M, Besler C, Batuca JR, Sangle S, Marques S, Sousa M, et al. Vascular abnormalities, paraoxonase activity, and dysfunctional HDL in primary antiphospholipid syndrome. JAMA. 2009;302:1210–1217. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Yu QS, Guo ZG. High density lipoproteins enhanced antiaggregating activity of nitric oxide derived from bovine aortal endothelial cells. Sheng Li Xue Bao. 2000a;52:81–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Silver DL, Smith JD, Tall AR. Scavenger receptor-BI inhibits ATP-binding cassette transporter 1-mediated cholesterol efflux in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2000b;275:30794–30800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Wu Y, Liu L, Su Y, Peng Y, Jiang L, et al. Relationship between high density lipoprotein antioxidant activity and carotid arterial intima-media thickness in patients with essential hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2010;32:13–20. doi: 10.3109/10641960902929487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenevard R, Hurlimann D, Spieker L, Bechir M, Enseleit F, Hermann M, et al. Reconstituted HDL in acute coronary syndromes. Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;30:e51–e57. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2010.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]