Abstract

Background and Purpose

PDE3 and/or PDE4 control ventricular effects of catecholamines in several species but their relative effects in failing human ventricle are unknown. We investigated whether the PDE3-selective inhibitor cilostamide (0.3–1 μM) or PDE4 inhibitor rolipram (1–10 μM) modified the positive inotropic and lusitropic effects of catecholamines in human failing myocardium.

Experimental Approach

Right and left ventricular trabeculae from freshly explanted hearts of 5 non-β-blocker-treated and 15 metoprolol-treated patients with terminal heart failure were paced to contract at 1 Hz. The effects of (-)-noradrenaline, mediated through β1 adrenoceptors (β2 adrenoceptors blocked with ICI118551), and (-)-adrenaline, mediated through β2 adrenoceptors (β1 adrenoceptors blocked with CGP20712A), were assessed in the absence and presence of PDE inhibitors. Catecholamine potencies were estimated from –logEC50s.

Key Results

Cilostamide did not significantly potentiate the inotropic effects of the catecholamines in non-β-blocker-treated patients. Cilostamide caused greater potentiation (P = 0.037) of the positive inotropic effects of (-)-adrenaline (0.78 ± 0.12 log units) than (-)-noradrenaline (0.47 ± 0.12 log units) in metoprolol-treated patients. Lusitropic effects of the catecholamines were also potentiated by cilostamide. Rolipram did not affect the inotropic and lusitropic potencies of (-)-noradrenaline or (-)-adrenaline on right and left ventricular trabeculae from metoprolol-treated patients.

Conclusions and Implications

Metoprolol induces a control by PDE3 of ventricular effects mediated through both β1 and β2 adrenoceptors, thereby further reducing sympathetic cardiostimulation in patients with terminal heart failure. Concurrent therapy with a PDE3 blocker and metoprolol could conceivably facilitate cardiostimulation evoked by adrenaline through β2 adrenoceptors. PDE4 does not appear to reduce inotropic and lusitropic effects of catecholamines in failing human ventricle.

Linked Article

This article is commented on by Eschenhagen, pp 524–527 of this issue. To view this commentary visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.12168

Keywords: human heart failure, β1 and β2 adrenoceptors, phosphodiesterases 3 and 4, noradrenaline and adrenaline, inotropism and lusitropism, metoprolol

Introduction

Activation of β1 and β2 adrenoceptors of human failing ventricle by noradrenaline and adrenaline causes similar inotropic, lusitropic and biochemical effects through the cAMP/cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) pathway (Kaumann et al., 1999). PDEs break down cAMP. At least 21 genes of 11 PDE families are known (Bender and Beavo, 2006). The cAMP-hydrolysing isoenzymes PDE1, PDE2, PDE3, PDE4 and PDE8 are expressed in mammalian heart and PDE3 is particularly highly expressed in human myocardium (Osadchii, 2007). PDE3 is relevant to heart failure in which cardiac cAMP levels and function are depressed (Von der Leyen et al., 1991). By preventing cAMP hydrolysis, PDE3 inhibitors (e.g. milrinone and enoximone) enhance cardiac contractility through activation of cAMP-dependent pathways. Short-lasting infusions or low-dose oral treatment with PDE3 inhibitors have been shown to improve systolic function in chronic heart failure (Van Tassel et al., 2008). In contrast, high-dose chronic treatment with PDE3 inhibitors worsens heart failure and increases mortality, particularly through sudden death (Amsallem et al., 2005). We hypothesize that the PDE3 activity in severe heart failure further reduces harmful cardiostimulation by endogenous catecholamines in β-blocker-treated patients. It is unknown whether blockade of β1 adrenoceptors and/or β2 adrenoceptors in heart failure (Bristow, 2000) can modify PDE3 activity.

PDE4 is also expressed in human myocardium (Osadchii, 2007) and in particular PDE4D (Johnson et al., 2012), but its functions are not yet clear. PDE4D3 is an integral component of the murine and human cardiac ryanodine RyR2 receptor complex, and it is reduced in murine and human heart failure (Lehnart et al., 2005). Therefore, PDE4D3 plausibly may affect catecholamine-evoked contractility. PDE4 controls the inotropic effects and cAMP signals of catecholamines, mediated through β1 adrenoceptors in rodent myocardium (Nikolaev et al., 2006; Rochais et al., 2006; Galindo-Tovar and Kaumann, 2008; Christ et al., 2009) but not in human atrium (Christ et al., 2006a; Kaumann et al., 2007). However, it is unknown whether PDE4 controls human ventricular effects of catecholamines and whether it is through β1 adrenoceptors and/or β2 adrenoceptors.

We now investigated whether the inotropic and lusitropic effects of the catecholamines, mediated through β1 or β2 adrenoceptors of ventricular trabeculae from patients with terminal heart failure, are enhanced by PDE3 inhibition with cilostamide and/or PDE4 inhibition with rolipram. We compared results from patients not treated with β-blocker or chronically treated with metoprolol. The results suggest that chronic treatment with metoprolol facilitates PDE3 activity to reduce the inotropic and lusitropic effects of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline, mediated through β1 and β2 adrenoceptors. PDE4 does not modify the effects of catecholamines.

A progress report of this work was presented to a Biochemical Society Meeting (Christ et al., 2006b).

Methods

Heart transplant patients

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Patients with terminal heart failure underwent heart transplant surgery at The Prince Charles Hospital, Brisbane, ethics approval numbers EC9876, HREC10/QPCH/184, and Gustav Carus Hospital, Dresden Technological University ethics committee (Document EK 1140 82202). Clinical data from Brisbane and Dresden patients are shown in Supporting Information Table S1A,B. Clinical data from Oslo patients are shown in Supporting Information Table S1C. All subjects or next of kin gave written informed consent to participate in the study, which was approved by the ethics committee in South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (#S05172).

Isolated ventricular trabeculae from heart transplant patients

Right or left ventricular trabeculae were dissected, mounted on to tissue electrode blocks and electrically paced at 1 Hz to contract as described (Kaumann et al., 1999). For further details see Supporting Information.

Specific activation of β1 and β2 adrenoceptors

To determine the effects of β1 adrenoceptor (Alexander et al., 2011) selective activation, concentration–effect curves for (-)-noradrenaline were obtained in the presence of ICI118551 (50 nM) to selectively block β2 adrenoceptors. To determine the effects of β2 adrenoceptor (Alexander et al., 2011) selective activation, concentration–effect curves for (-)-adrenaline were determined in the presence of CGP20712A (300 nM) to selectively block β1 adrenoceptors (Kaumann et al., 1999). To assess the influence of the PDE3-selective inhibitor cilostamide (300 nM–1 μM) and the PDE4-specific inhibitor rolipram (1–10 μM) on the effects of the catecholamines, a single concentration–effect curve for a catecholamine was obtained in the absence or presence of a PDE inhibitor. Trabeculae were incubated with PDE inhibitors for 30–45 min prior to commencement of catecholamine concentration–effect curves. At the completion of concentration–effect curves to catecholamines on right ventricular trabeculae, the effects of a maximal concentration of (-)-isoprenaline (200 μM) were determined. Since up to 20 contracting trabeculae were obtained from the same heart, it was often possible to compare the influence of the PDE inhibitors on responses mediated through both β1 and β2 adrenoceptors as shown in the representative experiment in Figure 3.

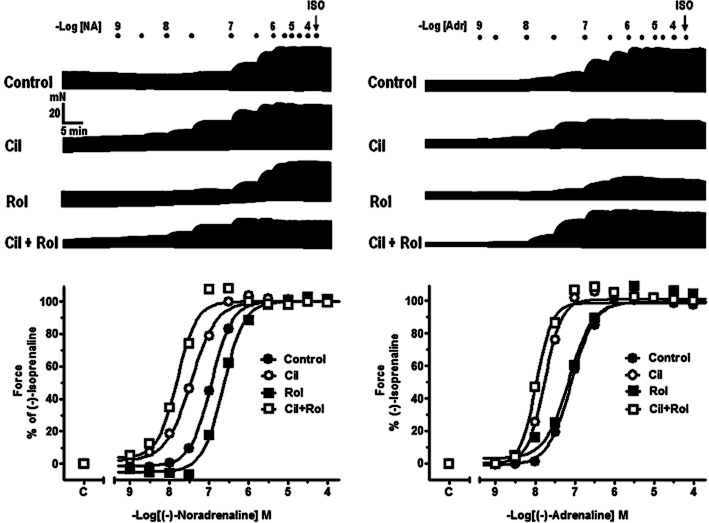

Figure 3.

Representative experiment carried out on right ventricular trabeculae obtained from a 48-year-old male patient with ischaemic heart disease, left ventricular ejection fraction 25 %, chronically administered metoprolol 142.5 mg daily. Shown are original traces for (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline in the absence or presence of cilostamide (Cil, 300 nM), rolipram (Rol, 1 μM), or Cil + Rol, followed by (-)-isoprenaline (ISO, 200 μM). The bottom panels show the corresponding graphical representation with non-linear fits. Note the clear potentiation of inotropic effects of both (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline in the presence of cilostamide but the lack of potentiation by rolipram.

Analysis and statistics

Responses of right ventricular trabeculae to catecholamines were expressed as percentage of the response to a maximally effective isoprenaline concentration (200 μM), administered after a complete concentration–effect curve. The catecholamine concentrations producing a half maximum response, –logEC50M (pEC50), were estimated from fitting a Hill function with variable slopes to concentration–effect curves from individual experiments. The data are expressed as mean ± SEM of n = number of patients or trabeculae as indicated. Significance of differences between means was assessed with the use of either Student's t-test or anova followed by Tukey–Kramer multiple comparisons ad hoc test at P < 0.05 using InStat software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Concentration–response curves on left ventricular trabeculae from Oslo patients were constructed by estimating centiles (EC10–EC100) for the receptor-selective effects for each experiment and calculating the corresponding means and the horizontal positioning expressed as −log EC50M. All results are expressed as mean ± SEM and statistical significance was assessed with one-way anova with a priori Bonferroni corrections made for multiple comparisons. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Drugs

(-)-Adrenaline (+)-bitartrate salt, (-)-noradrenaline bitartrate salt (hydrate), prazosin hydrochloride and atropine sulphate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA or Castle Hill, Australia). Rolipram, cilostamide, CGP20712A (2-hydroxy-5-[2-[[2-hydroxy-3-[4-[1-methyl-4-(trifluorometyl)-1H-imidazol-2-yl]phenoxy]propyl]amino]ethoxy]-benzamide) and ICI118551 (1-[2,3-dihydro-7-methyl-1H-inden-4-yl]oxy-3-[(1-methylethyl)amino]-2-butanol) were from Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK) or Sigma. Stock solutions were prepared in purified water and kept at −20°C to avoid oxidation. Further dilutions of the drugs were made fresh daily and kept cool (0–4°C) and dark. Repetitive experiments showed that drug solutions treated in these ways are stable.

Results

Chronic metoprolol treatment increases the inotropic potencies of catecholamines

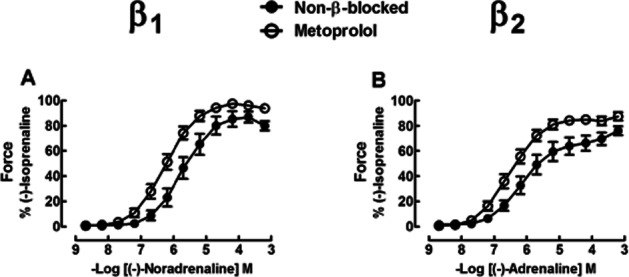

Chronic treatment of patients with metoprolol sensitized right ventricular trabeculae to the inotropic effects of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline. The inotropic potencies of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline were increased fourfold and fivefold, respectively, in metoprolol-treated (P < 0.05) compared with non-β-blocker-treated patients (Figure 1A and B, Table 1). The lusitropic effects of (-)-noradrenaline, mediated through β1 adrenoceptors, were not significantly enhanced but the t50-abbreviating potency of (-)-adrenaline increased sevenfold (P < 0.001) by treatment of patients with metoprolol (Supporting Information Fig. S1A–D, Supporting Information Table S2). These results are consistent with the up-regulation of the β1 adrenoceptor density and enhanced inotropic responses through these receptors in metoprolol-treated patients (Heilbrunn et al., 1989; Sigmund et al., 1996).

Figure 1.

Effects of chronic administration of metoprolol compared with no-β-blocker on inotropic effects of (-)-noradrenaline through activation of β1 adrenoceptors (A) and (-)-adrenaline through activation of β2 adrenoceptors (B) in right ventricular trabeculae from failing hearts. Note the increased potency of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline for inotropic effects in metoprolol-treated patients. See text and Table 1 for further detail. β adrenoceptor blockade did not significantly increase basal force [P = 0.07 for (-)-noradrenaline, P = 0.095 for (-)-adrenaline] and maximum force [P = 0.10 for (-)-noradrenaline, P = 0.054 for (-)-adrenaline]. Data from four [(-)-noradrenaline experiments] or five [(-)-adrenaline experiments] patients with heart failure not treated with a β-blocker and seven patients with heart failure treated with metoprolol.

Table 1.

Inotropic potencies of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline acting through ventricular β1 and β2 adrenoceptors respectively. Effects of cilostamide (300 nM right ventricle, 1 μM left ventricle) and rolipram (1 μM right ventricle, 10 μM left ventricle) and chronic metoprolol treatment

| (-)-Noradrenaline | (-)-Adrenaline | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-βB | Metoprolol treated | Non-βB | Metoprolol treated | |

| pEC50 (n) | pEC50 (n) | pEC50 (n) | pEC50 (n) | |

| Right ventricle | ||||

| Control | 5.65 ± 0.15 (11/4) | 6.25 ± 0.13 (18/7)* | 5.70 ± 0.27 (14/5) | 6.40 ± 0.11 (18/7)* |

| Cilostamide | 5.89 ± 0.24 (10/4) | 6.75 ± 0.17 (17/7) | 6.19 ± 0.27 (12/5) | 7.11 ± 0.16 (13/7)† |

| Rolipram | – | 6.19 ± 0.15 (15/7) | – | 6.50 ± 0.17 (12/7) |

| Left ventricle | ||||

| Control | – | 6.34 ± 0.16 (7/6) | – | 6.26 ± 0.16 (10/7) |

| Cilostamide | – | 6.77 ± 0.19 (7/6) | – | 6.93 ± 0.12 (8/7)†† |

| Rolipram | – | 6.25 ± 0.10 (7/6) | – | 6.29 ± 0.17 (8/7) |

Non-βB: not treated with β-blockers.

P < 0.05 versus non-βB.

P < 0.001 paired Student's t-test for comparison between cilostamide and control (no PDE inhibitor).

P < 0.05 versus control, one-way anova with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple a priori comparisons for comparison between cilostamide, rolipram and control.

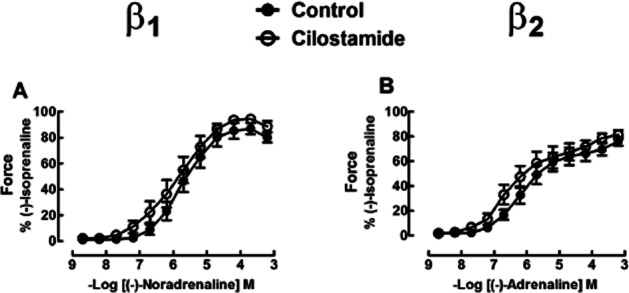

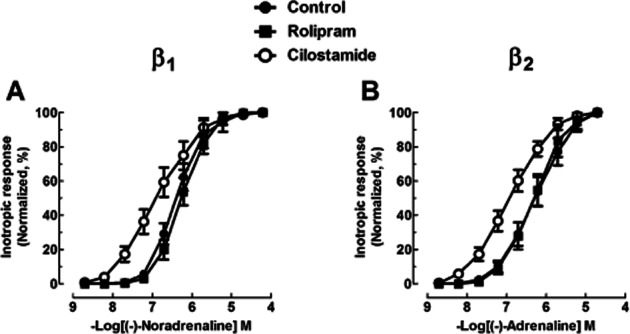

Cilostamide fails to potentiate the inotropic effects of catecholamines in right ventricular trabeculae from non-β-blocker-treated patients

Cilostamide (300 nM) did not significantly increase contractile force or hasten relaxation in the presence of ICI118551 or CGP20712A in trabeculae from non-β-blocker-treated patients. Cilostamide did not potentiate the positive inotropic effects of (-)-noradrenaline or (-)-adrenaline (Figure 2, Table 1). Cilostamide did not affect the lusitropic effects of (-)-noradrenaline (Supporting Information Fig. S2A,C, Table S2) but potentiated the (-)-adrenaline-evoked shortening of t50 (Supporting Information Fig. S2D, Table S2).

Figure 2.

Lack of effect of cilostamide on the inotropic responses of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline in right ventricular trabeculae from four [(-)-noradrenaline experiments] or five [(-)-adrenaline experiments] patients with heart failure not treated with a β-blocker. Shown are concentration–effect curves to (-)-noradrenaline (A) and (-)-adrenaline (B) in the absence or presence of cilostamide (300 nM). Cilostamide did not significantly increase basal force (P = 0.36 for the noradrenaline group, P = 0.46 for the adrenaline group) or enhance the maximum force caused by (-)-noradrenaline (P = 0.41) or (-)-adrenaline (P = 0.13).

Cilostamide potentiates more the effects mediated through β2 adrenoceptors than β1 adrenoceptors in ventricular trabeculae from metoprolol-treated patients

Cilostamide (300 nM) did not significantly change contractile force in the presence of ICI118551 or CGP20712A on right ventricular trabeculae. Cilostamide caused leftward shifts of the inotropic concentration–effect curves of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline as shown in the representative experiment in Figure 3. Inotropic results from right ventricular trabeculae of seven patients are shown in Figure 4. Cilostamide almost significantly increased the inotropic potency of (-)-noradrenaline (P = 0.06) (Figure 4A, Table 1). When data from right ventricular trabeculae of two additional metoprolol-treated Oslo patients (results not shown) were pooled with the data from seven Brisbane–Dresden patients, cilostamide significantly (P < 0.02, n = 9) potentiated the inotropic effects of (-)-noradrenaline. Cilostamide (300 nM) potentiated the effects of (-)-adrenaline on force (fivefold, P < 0.05, Figure 4B, Table 1). Cilostamide potentiated threefold the effects of (-)-noradrenaline on t50 (P < 0.05) but not time to peak force (TPF) (Supporting Information Fig. S3A,C, Table S2). Cilostamide potentiated the effects of (-)-adrenaline on TPF (threefold) and t50 (fourfold) respectively (both P < 0.05, Supporting Information Fig. S3B,D, Table S2).

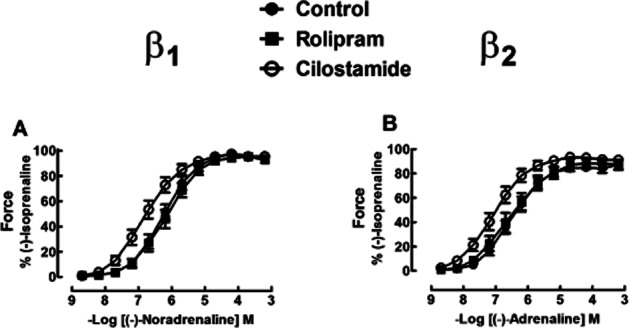

Figure 4.

Potentiation of the inotropic effects of (-)-adrenaline by cilostamide (P < 0.05) in right ventricular trabeculae from seven patients from Brisbane/Dresden with heart failure chronically administered with metoprolol (B). In the same hearts, cilostamide caused a leftward shift of the inotropic effects of (-)-noradrenaline (A) which was not quite significant (P = 0.06). Rolipram had no effect on the inotropic effects of (-)-noradrenaline or (-)-adrenaline. See text for further explanation. Shown are concentration–effect curves to (-)-noradrenaline (A) and (-)-adrenaline (B) in the absence or presence of cilostamide (300 nM) or rolipram (1 μM).

Cilostamide (1 μM) caused a non-significant (P < 0.07) leftward shift of the concentration–effect curve for the inotropic effects of (-)-noradrenaline on left ventricular trabeculae (P < 0.07, Figure 5A, Table 1), but potentiated the inotropic effects of (-)-adrenaline fivefold (P < 0.05, Figure 5B, Table 1).

Figure 5.

Cilostamide potentiates the inotropic effects of (-)-adrenaline in left ventricular trabeculae from seven [(-)-noradrenaline experiments] or eight Oslo patients [(-)-adrenaline experiments] with heart failure and chronically administered with metoprolol. Shown are concentration–effect curves to (-)-noradrenaline (A) and (-)-adrenaline (B) in the absence or presence of cilostamide (1 μM) or rolipram (10 μM). Inotropic data are normalized as a percentage of the maximal response to (-)-noradrenaline or (-)-adrenaline.

Cilostamide did not potentiate the TPF effects of (-)-noradrenaline or (-)-adrenaline on left ventricular trabeculae but potentiated the effects on time to reach 80% relaxation fourfold and fivefold respectively (both P < 0.05, Supporting Information Fig. S4, Table S3).

Cilostamide caused a non-significant trend of greater potentiation of the inotropic effects of (-)-adrenaline through β2 adrenoceptors (0.80 ± 0.11 log units, n = 9) than (-)-noradrenaline through β1 adrenoceptors in right ventricular trabeculae from metoprolol-treated patients (0.48 ± 0.18 log units, n = 9, Brisbane/Dresden/Oslo hearts) (P = 0.14, paired Student's t-test). However, when all right and left ventricular inotropic data from metoprolol-treated patients were pooled, cilostamide (0.3–1 μM) potentiated significantly more the β2-adrenoceptor-mediated effects of (-)-adrenaline (0.78 ± 0.12 log units, n = 15) than the β1-adrenoceptor-mediated effects of (-)-noradrenaline (0.47 ± 0.12 log units, n = 15) (P = 0.037). These results suggest that PDE3 limits more the inotropic responses through β2 adrenoceptor than β1 adrenoceptor.

Rolipram does not modify inotropic and lusitropic potencies of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline

Rolipram did not significantly modify force, TPF and t50 or t80 in right and left ventricular trabeculae incubated with ICI118551 or CGP20712A. The inotropic and lusitropic effects of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline were not significantly changed by rolipram (1 μM) in right ventricular trabeculae (inotropic: Figures 3 and 4, Table 1; lusitropic: Supporting Information Fig. S3, Table S2) and rolipram (10 μM) in left ventricular trabeculae (inotropic: Figure 5, Table 1; lusitropic: Supporting Information Fig. S4, Table S3).

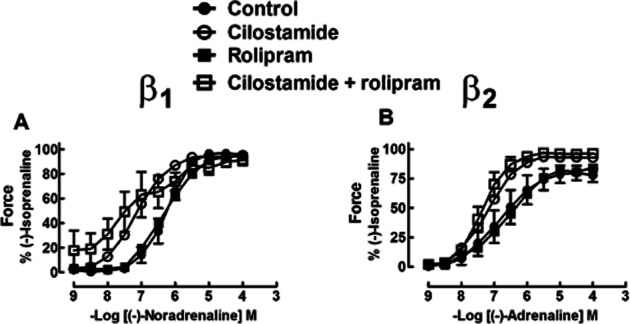

The effects of the combination of cilostamide (300 nM) and rolipram (1 μM) on the inotropic and lusitropic potencies of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline were investigated in three metoprolol-treated patients. Cilostamide + rolipram potentiated the inotropic [(-)-noradrenaline P < 0.05; (-)-adrenaline P < 0.05] and lusitropic [(-)-noradrenaline TPF, t50 both P < 0.05; (-)-adrenaline TPF, t50 both P < 0.05] effects of both (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline, but the degree of potentiation did not significantly (P > 0.05) differ from the potentiation caused by cilostamide alone (inotropic: Figure 6; lusitropic: Supporting Information Fig. S5).

Figure 6.

Effects of the combination of cilostamide and rolipram on the inotropic responses of (-)-noradrenaline (A) and (-)-adrenaline (B) in right ventricular trabeculae from three patients with heart failure and chronically administered with metoprolol. While the combination of cilostamide and rolipram potentiated the inotropic responses of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline, the degree of potentiation did not differ from that caused by cilostamide alone.

Discussion

Our work revealed two important aspects of the control by PDEs of the inotropic effects of catecholamines. Chronic treatment of heart failure patients with metoprolol induced PDE3 to reduce the inotropic responses more through β2 adrenoceptors than β1 adrenoceptors. PDE4 appears not to be involved in the inotropic and lusitropic control at all.

Control by PDE3 of the function of β1 and β2 adrenoceptors in heart failure patients treated with metoprolol

PDE3 activity is stimulated by activation of β1 adrenoceptors and β2 adrenoceptors, which in turn causes a negative feedback by hydrolysing cAMP and thereby reducing inotropic and lusitropic effects. A tonic receptor activation by endogenous catecholamines increases cAMP and PKA activity in a compartment that allows the latter to phosphorylate and activate PDE3 (Gettys et al., 1987), which in turn hydrolyses cAMP. This effect is likely to be more important for β2 adrenoceptors, at least in human heart, because these receptors are more efficient than β1 adrenoceptors at activating Gs and stimulating ventricular adenylyl cyclase (Kaumann and Lemoine, 1987), as verified with recombinant receptors (Levy et al., 1993). Therefore, inhibition of PDE3 may potentiate β2-adrenoceptor-mediated responses more than β1-adrenoceptor-mediated responses, as shown here for human failing ventricle and previously for non-failing atrial myocardium from patients without heart failure (Christ et al., 2006a).

A reduction in the expression and activity of PDE3 has been reported in heart failure patients (Silver et al., 1990; Ding et al., 2005a,b). Treatment with isoprenaline causes sustained down-regulation of PDE3A (Ding et al., 2005b), as also observed in human heart failure and animal heart failure models (Ya and Abe, 2007), presumably due to the high catecholamine plasma levels. A down-regulation of PDE3A would be expected to increase cAMP levels in heart failure so that inhibition of the enzyme would conceivably affect the effects of catecholamines less. The lack of significant potentiation by cilostamide of the inotropic and lusitropic effects of both (-)-noradrenaline through β1 adrenoceptors and marginal potentiation of the effects of adrenaline through β2 adrenoceptors in our five non-β-blocked patients is consistent with this expectation. In contrast, chronic treatment of heart failure patients with metoprolol revealed robust potentiation of the inotropic and lusitropic effects of the catecholamines through β1 and β2 adrenoceptors. We speculate that this effect of metoprolol is due to chronic β adrenoceptor blockade, thereby preventing the suppressing effects of endogenous catecholamines on PDE3 activity.

The increased β2-adrenoceptor-mediated ventricular inotropic and lusitropic effects in ventricular trabeculae caused by metoprolol treatment of heart failure patients agree with a similar (sixfold) enhancement of the β2-adrenoceptor-mediated inotropic potency of (-)-adrenaline in human atria obtained from patients without heart failure chronically treated with atenolol (Hall et al., 1990). The increased cardiac responsiveness to adrenaline through β2 adrenoceptors appears to be the result of chronic β1 adrenoceptor blockade. Experimental long-lasting exposure to catecholamines elicits up-regulation of Giα (Eschenhagen et al., 1992). A similar situation occurs in heart failure in which the sympathetic nervous system is hyperactive (Cohn, 1989), plasma noradrenaline levels are increased (Thomas and Marks, 1978) and ventricular Giα increased (Neumann et al., 1988). Human β2 adrenoceptors can couple to and activate Giα, in addition to Gsα, when they are stimulated by a very high isoprenaline concentration in human atrium (Kilts et al., 2000). Through chronic β1 adrenoceptor blockade of patients by treatment with metoprolol or possibly atenolol, the noradrenaline-induced elevation of Giα ceases, Giα levels are reduced (Sigmund et al., 1996), conceivably thereby favouring coupling of β2 adrenoceptor to Gsα to allow enhanced inotropic and lusitropic effects of adrenaline through β2 adrenoceptors. This hypothesis requires future research.

Our results suggest that chronic β adrenoceptor blockade facilitates the control by PDE3s of catecholamine effects, particularly through β2 adrenoceptors. However, the generality of this argument has to be restricted to heart failure, or it runs afoul because in atrial myocardium obtained from patients without heart failure we observed that cilostamide potentiated the effects of adrenaline, mediated through β2 adrenoceptors, more than the effects of noradrenaline, mediated through β1 adrenoceptors, regardless of whether or not patients had been treated with β1 adrenoceptor-selective blockers (Christ et al., 2006a). Changes of ventricular β2 adrenoceptor function in heart failure (Nikolaev et al., 2010) and profound anatomical differences between ventricle and atrium (Bootman et al., 2011) may be relevant to account for the different consequences of PDE3 control in the two tissues with respect to β1 adrenoceptor and β2 adrenoceptor function after chronic β adrenoceptor blockade.

The lusitropic (Supporting Information Figs S3–5, Tables S2, S3) effects mediated through β1 and β2 adrenoceptors were usually potentiated by cilostamide to a similar extent as the corresponding inotropic effects in trabeculae from β-blocker-treated patients (Figures 6, Table 1). PDE3 activity in human ventricle is associated with membrane vesicle-derived t-tubules and junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), causing hydrolysis of cAMP in the vicinity of phospholamban (PLB) (Movsesian et al., 1991; Lugnier et al., 1993). In ventricular myocardium from failing hearts, noradrenaline and adrenaline produce similar increases in PKA-catalysed phosphorylation of the proteins mediating myocardial relaxation, PLB (at Ser16), troponin-I (TnI) and cardiac myosin-binding protein-C (Kaumann et al., 1999). Our lusitropic results are consistent with an increased phosphorylation of PLB, TnI and myosin-binding protein-C by isoprenaline in the presence of the PDE3 inhibitor pimobendan in human failing myocardium (Bartel et al., 1996).

PDE4 inhibition does not affect the inotropic and lusitropic effects of catecholamines

PDE4 isoenzymes, their subtypes and splicing variants, are equally expressed in rodent and human ventricle but murine hearts have a considerably higher PDE4 activity than human hearts (Richter et al., 2011). Inhibition of PDE4 causes potentiation of the positive inotropic effects mediated through rodent β1 adrenoceptors (Kaumann, 2011). In contrast, our results from human failing ventricle demonstrate that inhibition of PDE4 with rolipram did not potentiate the positive inotropic and lusitropic effects of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline, mediated through β1 and β2 adrenoceptors respectively. It could be argued that we were unable to demonstrate a potentiating effect of rolipram because PDEs, including PDE4s, are down-regulated in heart failure (Ding et al., 2005a,b; Lehnart et al., 2005). However, we have also reported for human atrial myocardium, obtained from non-failing hearts, that rolipram failed to potentiate the positive inotropic effects of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline mediated through β1 and β2 adrenoceptors (Christ et al., 2006a; Kaumann et al., 2007). Our findings are consistent with an early report demonstrating that cilostamide but not rolipram inhibited SR-associated PDE activity in human ventricle from heart failure patients (Movsesian et al., 1991).

Taken together, our present results and a critical appraisal of the literature make it unlikely that PDE4s modulate human inotropic and lusitropic effects of catecholamines, mediated through both β1 and β2 adrenoceptors in non-failing and failing hearts. Moreover, extrapolation of results from the PDE4 function in mouse and rat hearts to human inotropic and lusitropic effects of physiological catecholamines can actually be misleading. However, PDE4s can reduce the occurrence of catecholamine-evoked arrhythmias in murine ventricle (Galindo-Tovar and Kaumann, 2008; Lehnart et al., 2005) and apparently in human atrium (Molina et al., 2012). However, clinical trials with a PDE4 inhibitor, roflumilast, have not provided evidence for cardiovascular side effects in approximately 1500 roflumilast-treated patients compared with 1500 placebo patients (Calverley et al., 2009). A comparison between human and other species of the control of β1-adrenoceptor and β2-adrenoceptor-mediated inotropy and lusitropy by PDE3 and PDE4, as well as protection against arrhythmias, is summarized in Supporting Information Table S4.

Clinical implications

Although we did not detect a direct inotropic change with cilostamide, this PDE3 inhibitor potentiated the inotropic effects of the endogenous catecholamines mediated through ventricular β1 and β2 adrenoceptors of metoprolol-treated patients, consistent with PDE3 inhibition. The induction of PDE3 activity in metoprolol-treated patients could further reduce cardiostimulation by endogenous catecholamines.

We found on human atrium that metoprolol blocks the effects of catecholamines through β1 adrenoceptors only by 2.5-fold more than β2 adrenoceptors (Supporting Information Fig. S6). We predict that heart failure patients under therapy with a PDE3 inhibitor + metoprolol could be at risk of not being protected against adverse stress-induced surges of adrenaline, acting through β2 adrenoceptors. From simple competitive inhibition, the concentration ratio (CR) of a catecholamine in the presence and absence of metoprolol can be calculated from CR = 1 + ([metoprolol] × KB−1). The therapeutic plasma level of 100 ng·mL−1 (310 nM) metoprolol (Kindermann et al., 2004) which hardly binds to plasma proteins, using KB values of 40 nM for β1 adrenoceptors and 98 nM for β2 adrenoceptors (Supporting Information Fig. S6), would produce CR values of 8.8 for β1 adrenoceptors and 4.2 for β2 adrenoceptors. The fivefold potentiation of the inotropic effects of (-)-adrenaline by cilostamide suggests that endogenous increases in plasma (-)-adrenaline could conceivably surmount the β2 adrenoceptor blockade caused by metoprolol in patients also treated with a PDE3 inhibitor.

Conclusions

Treatment with metoprolol induces the control by PDE3 of the ventricular inotropic and lusitropic effects of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline through β1 adrenoceptors and β2 adrenoceptors, respectively, plausibly by restoring the decreased activity and expression of PDE3 in heart failure. Quantitative considerations, based on differences in the affinity profile of metoprolol for β1 and β2 adrenoceptors, suggest that treatment with a PDE3-selective inhibitor could potentially facilitate adverse stress-induced adrenaline effects through β2 adrenoceptors in patients treated with metoprolol. PDE4 does not control the inotropic and lusitropic effects mediated through β1 and β2 adrenoceptors in human heart.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the heart surgeons of The Prince Charles Hospital Brisbane, Carl Gustav Carus Hospital Dresden, and Oslo University Hospital-Rikshospitalet, Oslo. Research at The Prince Charles Hospital (Brisbane) was supported in part by The Prince Charles Hospital Foundation. The research in Oslo was supported by The Norwegian Council on Cardiovascular Disease, The Research Council of Norway, Stiftelsen Kristian Gerhard Jebsen, Anders Jahre's Foundation for the Promotion of Science, The Family Blix Foundation, The Simon Fougner Hartmann Foundation, South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority, and the University of Oslo.

Glossary

- β-blocker

β-adrenoceptor blocker (antagonist)

- CGP20712A

(2-hydroxy-5-[2-[[2-hydroxy-3-[4-[1-methyl-4-(trifluorometyl)-1H-imidazol-2-yl]phenoxy]propyl]amino]ethoxy]-benzamide)

- CR

concentration ratio

- ICI118551

(1-[2,3-dihydro-7-methyl-1H-inden-4-yl]oxy-3-[(1-methylethyl)amino]-2-butanol)

- PKA

cAMP-dependent protein kinase

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- t50

time to 50% relaxation

- TPF

time to peak force

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Figure S1 Effects of chronic administration of metoprolol compared with no-β-blocker on lusitropic effects [time to peak force and time to 50% relaxation (t50)] of (-)-noradrenaline through activation of β1 adrenoceptors (A,C) and (-)-adrenaline through activation of β2 adrenoceptors (B,D) in right ventricular trabeculae from failing hearts. Data from four [(-)-noradrenaline experiments] or five [(-)-adrenaline experiments] patients with heart failure not treated with a β-blocker and seven patients with heart failure treated with metoprolol.

Figure S2 Effect of cilostamide on the lusitropic responses of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline in right ventricular trabeculae from four [(-)-noradrenaline experiments] or five [(-)-adrenaline experiments] patients with heart failure not treated with a β-blocker. Shown are concentration–effect curves to (-)-noradrenaline (A,C) and (-)-adrenaline (B,D) in the absence or presence of cilostamide (300 nM). Cilostamide potentiated the (-)-adrenaline-evoked hastening of relaxation (shortening of t50).

Figure S3 Cilostamide, but not rolipram, potentiates the lusitropic effects of (-)-adrenaline and (-)-noradrenaline in right ventricular trabeculae from seven patients with heart failure chronically administered with metoprolol. Shown are concentration–effect curves to (-)-noradrenaline (A,C) and (-)-adrenaline (B,D) in the absence or presence of cilostamide (300 nM) or rolipram (1 μM).

Figure S4 Cilostamide, but not rolipram, potentiates the relaxant effects of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline in left ventricular trabeculae from seven [(-)-noradrenaline experiments] or eight Oslo patients [(-)-adrenaline experiments] with heart failure chronically administered with metoprolol. Shown are concentration–effect curves to (-)-noradrenaline (A,C) and (-)-adrenaline (B,D) in the absence or presence of cilostamide (1 μM) or rolipram (10 μM). See Supporting Information Table S3 for analysis.

Figure S5 Effects of the combination of cilostamide (300 nM) and rolipram (1 μM) on the lusitropic responses of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline in right ventricular trabeculae from three patients with heart failure chronically administered with metoprolol. While the combination of cilostamide and rolipram potentiated the lusitropic responses of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline, the degree of potentiation did not differ from that caused by cilostamide alone.

Figure S6 Determination of the affinity of metoprolol at β1 and β2 adrenoceptors in human right atrium. Shown are cumulative concentration–effect curves for (-)-noradrenaline at β1 adrenoceptors (A) and (-)-adrenaline at β2 adrenoceptors (B) in the absence and presence of metoprolol. Numbers in parentheses are (trabeculae/patients). The corresponding Schild plots are shown in (C).

Table S1 Summary of patients.

Table S2 Lusitropic potencies of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline acting through right ventricular β1 and β2 adrenoceptors respectively. Effects of cilostamide (300 nM) and rolipram (1 μM) in non-β-blocker-treated (non-βB) and chronic metoprolol-treated patients.

Table S3 Lusitropic potencies of (-)-noradrenaline and (-)-adrenaline acting through left ventricular β1 and β2 adrenoceptors of metoprolol-treated patients. Effects of cilostamide (1 μM) and rolipram (10 μM).

Table S4 Reduction of inotropic and lusitropic responses as well as protection against arrhythmias, mediated through myocardial β1 and β2 adrenoceptors, by PDE3 and PDE4 in different species.

References

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 5th edition. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164(Suppl. 1):S1–S324. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01649_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsallem E, Kasparian C, Haddour G, Boissel JP, Nony P. Phosphodiesterase III inhibitors for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002230.pub2. CD002230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel S, Stein B, Eschenhagen T, Mende U, Neumann J, Schmitz W, et al. Protein phosphorylation in isolated trabeculae from nonfailing and failing hearts. Mol Cell Biochem. 1996;157:171–179. doi: 10.1007/BF00227896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender AT, Beavo JA. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: molecular regulation to clinical use. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:488–520. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootman MD, Smyrnias J, Thul R, Coombes S, Roderick HL. Atrial cardiomyocyte calcium signaling. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:922–934. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow MR. β-Adrenergic receptor blockade in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2000;101:558–569. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.5.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calverley PM, Rabe KF, Goehring UM, Kristiansen S, Fabri LM, Martinez FJ. Roflumilast in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: two randomized clinical trials. Lancet. 2009;374:685–694. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ T, Engel A, Ravens U, Kaumann AJ. Cilostamide potentiates more the positive inotropic effects of (-)-adrenaline through β2-adrenoceptors than the effects of (-)-noradrenaline through β1-adrenoceptors in human atrial myocardium. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2006a;374:249–253. doi: 10.1007/s00210-006-0119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ T, Molenaar P, Galindo-Tovar A, Ravens U, Kaumann AJ. Contractile responses through Gs-coupled receptors are reduced by phosphodiesterase3 activity in human isolated myocardium. 2006b. Compartmentalization of cyclic AMP signalling P014, Biochemical Society Meeting, Cambridge, UK.

- Christ T, Galindo-Tovar A, Thoms M, Ravens U, Kaumann AJ. Inotropy and L-type Ca2+ current, activated by β1- and β2-adrenoceptors, are differently controlled by phosphodiesterases 3 and 4 in rat heart. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:62–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn JN. The sympathetic nervous system in heart failure. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1989;14:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding B, Abe J, Wei H, Huang Q, Walsh RA, Molina CA, et al. Functional role of phosphodiesterase 3 in cardiomyocyte apoptosis: implication in heart failure. Circulation. 2005a;111:2469–2476. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000165128.39715.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding B, Abe J, Wei H, Huang Q, Xu H, Aizawa T, et al. A positive feedback loop of phosphodiesterase 3 (PDE3) and inducible cAMP early repressor (ICER) leads to cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005b;102:14771–14776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506489102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschenhagen T, Mende U, Diedrich M, Nose M, Schmitz W, Scholz H, et al. Long term β-adrenoceptor up-regulation of Giα and Goα mRNA levels and pertussis toxin-sensitive guanine nucleotide binding-proteins in rat heart. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;42:773–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo-Tovar A, Kaumann AJ. Phosphodiesterase-4 blunts inotropism and arrhythmias but not sinoatrial tachycardia of (-)-adrenaline mediated through mouse cardiac β1-adrenoceptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:710–720. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gettys TW, Blackmore PF, Redmon JB, Beebe SJ, Corbin JD. Short-term feedback regulation of cAMP by accelerated degradation in rat tissues. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:333–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JA, Kaumann AJ, Brown MJ. Selective beta 1-adrenoceptor blockade enhances positive inotropic responses to endogenous catecholamines mediated through beta 2-adrenoceptors in human atrium. Circ Res. 1990;66:1610–1623. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.6.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilbrunn SM, Shah P, Bristow MR, Valantine HA, Ginsburg R, Fowler MB. Increased β-receptor density and improved hemodynamic responses to catecholamine stimulation during long-term metoprolol therapy in heart failure from dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1989;70:483–490. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WB, Katugampola S, Able S, Napier C, Harding SE. Profiling of cAMP and cGMP phosphodiesterases in isolated ventricular cardiomyocytes from human hearts: comparison with rat and guinea pig. Life Sci. 2012;90:328–336. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaumann AJ. Phosphodiesterases reduce spontaneous sinoatrial beating but not the ‘fight or flight’ tachycardia elicited by agonists through Gs-protein coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:377–383. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaumann AJ, Lemoine H. β2-adrenoceptor-mediated positive inotropic effect of adrenaline in human ventricular myocardium. Quantitative discrepancies with binding and adenylate cyclase stimulation. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1987;335:403–411. doi: 10.1007/BF00165555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaumann AJ, Bartel S, Molenaar P, Sanders L, Burrell K, Vetter D, et al. Activation of β2-adrenergic receptors hastens relaxation and mediates phosphorylation of phospholamban, troponin I, and C-protein in ventricular myocardium from patients with terminal heart failure. Circulation. 1999;99:65–72. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaumann AJ, Semmler AL, Molenaar P. The effects of both noradrenaline and CGP12177, mediated through human β1-adrenoceptors, are reduced by PDE3 in human atrium but PDE4 in CHO cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2007;375:123–131. doi: 10.1007/s00210-007-0140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilts JD, Gerhardt MA, Richardson MD, Sreeram G, Mackensen GB, White WD, et al. β2-adrenergic and several other G protein-coupled receptors in human atrial membranes activate both Gs and Gi. Circ Res. 2000;87:635–637. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.8.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindermann M, Maack C, Schaller S, Finkler N, Schmidt KI, Läer S, et al. Carvedilol but not metoprolol reduces β-adrenergic responsiveness after complete elimination from plasma in vivo. Circulation. 2004;109:3182–3190. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130849.08704.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehnart SE, Wehrens XH, Reiken S, Warrier S, Belevych AE, Harvey RD, et al. Phosphodiesterase 4D deficiency in the ryanodine-receptor complex promotes heart failure and arrhythmias. Cell. 2005;123:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy FO, Zhu X, Kaumann AJ, Birnbaumer L. Efficacy of β1-adrenergic receptors is lower than that of β2-adrenergic receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10798–17802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugnier C, Muller B, Le Bec A, Beaudry C, Rousseau E. Characterization of indolidan- and rolipram-sensitive cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases in canine and human cardiac microsomal fractions. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265:1142–1151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina CE, Leroy J, Richter W, Xie M, Scheitrum C, Illkyu-Oliver L, et al. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate phosphodiesterase type 4 protects against atrial arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:2182–2190. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movsesian MA, Smith CJ, Krall J, Bristow MR, Manganiello VC. Sarcoplasmic reticulum-associated cyclic adenosine 5′-monophosphate phosphodiesterase activity in normal and failing human hearts. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:15–19. doi: 10.1172/JCI115272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann J, Schmitz W, Scholz H, von Meyerinck L, Döring V, Kalmar P. Increase in myocardial Gi-proteins in heart failure. Lancet. 1988;2:936–937. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)92601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev VO, Bunemann M, Schmitteckert E, Lohse MJ, Engelhardt S. Cyclic AMP imaging in adult cardiac myocytes reveals far-reaching β1-adrenergic receptor-mediated signalling. Circ Res. 2006;99:1084–1091. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250046.69918.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev VO, Moshkov A, Lyon AR, Miragoli M, Novak P, Paur H, et al. β2-adrenergic receptor redistribution in heart failure changes cAMP compartmentation. Science. 2010;327:1653–1657. doi: 10.1126/science.1185988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osadchii OE. Myocardial phosphodiesterases and regulation of cardiac contractility in health and cardiac disease. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2007;21:171–194. doi: 10.1007/s10557-007-6014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter W, Xie M, Scheitrum C, Krall J, Movsesian MA, Conti M. Conserved expression and functions of PDE4 in rodent and human heart. Basic Res Cardiol. 2011;106:249–262. doi: 10.1007/s00395-010-0138-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochais F, Abi-Gerges A, Horner K, Lefebvre F, Cooper DM, Conti M, et al. A specific pattern of phosphodiesterases controls the cAMP signals generated by different Gs-coupled receptors in adult rat ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 2006;2006:1081–1088. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000218493.09370.8e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigmund M, Jacob H, Becker H, Hanrath P, Schumacher C, Eschenhagen T, et al. Effects of metoprolol on myocardial β-adrenoceptors and Gi?-proteins in patients with congestive heart failure. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;51:127–132. doi: 10.1007/s002280050172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver P, Allen P, Etzler JH, Hamel LT, Bentley RG, Pagani ED. Cellular distribution and pharmacological sensitivity of low KM cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase isoenzymes in human cardiac muscle from normal and cardiomyopathic subjects. Second Messengers Phosphoproteins. 1990;13:13–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JA, Marks BH. Plasma norepinephrine in congestive heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 1978;41:233–243. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(78)90162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tassel BW, Radwanski P, Movsesian M, Munger MA. Combination therapy with β-adrenergic receptor antagonists and phosphodiesterase inhibitors for chronic heart failure. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28:1523–1530. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.12.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von der Leyen H, Mende U, Meyer W, Neumann J, Nose M, Schmitz W, et al. Mechanism underlying the reduced positive inotropic effects of the phosphodiesterase III inhibitors pimobendan, adibendan and saterinone in failing as compared to non-failing human cardiac muscle preparations. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1991;344:90–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00167387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ya C, Abe J. Regulation of phosphodiesterase3 and inducible cAMP early repressor in the heart. Circ Res. 2007;100:489–501. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258451.44949.d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.