Abstract

Background and Purpose

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) has been implicated in the regulation of adhesion molecules, leukocyte adhesion and infiltration into inflamed site. However, the underlying mechanism therein involved remains ill-defined. In this study, we explored its cellular mechanism of action in the regulation of the intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression in the brain endothelial cells.

Experimental Approach

bEnd.3 cells, the murine cerebrovascular endothelial cell line and primary mouse brain endothelial cells were treated with PGE2 with or without agonists/antagonists of PGE2 receptors and associated signalling molecules. ICAM-1 expression, Akt phosphorylation and activity of NF-κB were determined by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), immunoblot analysis, luciferase assay and immunocytochemistry.

Key Results

PGE2 significantly up-regulated the expression of ICAM-1, which was blocked by EP4 antagonist (ONO-AE2-227) and knock-down of EP4. PGE2 effects were mimicked by forskolin, dibutyryl cAMP (dbcAMP) and an exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac) activator (8-Cpt-cAMP) but not a protein kinase A activator (N6-Bnz-cAMP). PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression was reduced by knock-down of Epac1. A PI3K specific inhibitor (LY294002), Akt inhibitor VIII (Akti) and NF-κB inhibitors (Bay-11–7082 and MG-132) attenuated the induction of ICAM-1 by PGE2. PGE2, dbcAMP and 8-Cpt-cAMP induced the phosphorylation of Akt, IκB kinase and IκBα and the translocation of p65 to the nucleus and increased NF-κB dependent reporter gene activity, which was diminished by Akti.

Conclusion and Implications

Our findings suggest that PGE2 induces ICAM-1 expression via EP4 receptor and Epac/Akt/NF-κB signalling pathway in bEnd.3 brain endothelial cells, supporting its pathophysiological role in brain inflammation.

Keywords: prostaglandin E2, intercellular adhesion molecule 1, cerebrovascular endothelial cell, EP4 receptor, exchange protein activated by cAMP, PI3K/Akt, nuclear factor-κB

Introduction

Leukocyte adhesion to cerebrovascular endothelial cells and subsequent infiltration into brain parenchyma is crucial in developing brain tissue injury during various neuropathological processes including brain infection, trauma and cerebral ischaemia. Activated endothelial cells present a proadhesive surface to leukocytes, promoting leukocyte recruitment during an inflammatory response (Carlos and Harlan, 1994; Langer and Chavakis, 2009). Leukocyte adhesion to activated endothelial cells is a sequential, multistep process consisting of tethering, rolling, firm adhesion and transmigration (Springer, 1994). Each step requires interaction between leukocytes and distinct adhesion molecules expressed on the endothelial cell surface. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), a member of the immunoglobulin (Ig) gene superfamily of cellular adhesion molecules, is involved in the firm adhesion of leukocyte to endothelial surface by interacting with leukocyte integrins. Increased leukocyte adhesion and infiltration under various pathological conditions is accompanied by increased expression of endothelial ICAM-1 (Springer, 1994; Rossi et al., 2011) and the blockade of ICAM-1 ligation limits leukocyte infiltration and ameliorates brain damage (Bowes et al., 1993; Vemuganti et al., 2004; Arumugam et al., 2009). The induction of ICAM-1 is regulated by a myriad of factors secreted at the site of injury, including cytokines, chemokines, prostaglandins and free radicals (Carlos and Harlan, 1994; Winkler et al., 1997; Bernot et al., 2005).

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a COX product of arachidonic acid released from membrane phospholipids, plays important roles in regulating brain injury and inflammation (Andreasson, 2010; Legler et al., 2010). Levels of PGE2 in CNS are up-regulated in various neurological disorders including ischaemic stroke, Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease (Aktan et al., 1991; Minghetti, 2004; Cimino et al., 2008). The relevance of PGE2 in the process of inflammatory brain injury is underscored by the effectiveness of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as COX inhibitors (Hurley et al., 2002; Minghetti, 2004; Simmons et al., 2004; Aid and Bosetti, 2011). As a classical inflammatory mediator, PGE2 has been implicated in the tissue influx of leukocytes and the expression of adhesion molecules (Kalinski, 2012). However, the role of PGE2 in the regulation of ICAM-1 expression is likely to be context specific. While PGE2 increases ICAM-1 expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (Winkler et al., 1997) and oral cancer cells (Yang et al., 2010), it suppresses cytokine- or endotoxin-induced ICAM-1 expression in human vascular smooth muscle cells (Bishop-Bailey et al., 1998) and fibroblasts (Noguchi et al., 2001). These observations indicate that PGE2 exerts differential effects on the expression of adhesion molecules in the course of inflammation, depending on the cell types and pathologic conditions. PGE2 acts locally through binding of one or more of its four different receptors designated (E-prostanoid) EP1-EP4. The EP subtypes exhibit differences in sensitivity, signal transduction, tissue localization and regulation of expression. This molecular and biochemical heterogeneity of PGE2 receptors permits distinctive effects of PGE2 in different cell types at different stages of inflammation. Thus, it is highly plausible that in addition to the alteration in PGE2 production, the regulation of PGE2 responsiveness at the level of individual PGE2 receptors can also contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammatory disease (Kalinski, 2012).

Despite its implication in inflammatory brain injury, the role of PGE2 in the regulation of ICAM-1 expression in CNS remains ill defined. COX inhibitors, NS-398, indomethacin and dexamethasone are reported to attenuate ICAM-1 expression induced by IL-1, ischaemia and ionizing radiation in cerebrovascular endothelial cells and brain tissues (Stanimirovic et al., 1997; Kyrkanides et al., 2002). In the previous study, we also observed COX inhibitors diminished cadmium-induced ICAM-1 expression in brain endothelial cells, which was reversed by addition of PGE2 (Seok et al., 2006). However, the details of effect of PGE2 on ICAM-1 expression in brain endothelial cells are largely unknown. Thus, in order to better understand the role of PGE2 in brain inflammation, we examined the effects of PGE2 on ICAM-1 expression and leukocyte adhesion to brain endothelial cells and explored underlying mechanisms therein involved. Our findings demonstrate that exogenous PGE2 induces ICAM-1 expression in cerebrovascular endothelial cells and promotes leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cell monolayers via EP4 receptor and Epac/Akt/NF-κB signalling pathway.

Methods

Cell culture

bEnd.3 cells, the murine brain cerebrovascular endothelial cell line, were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were maintained in DMEM (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U·mL−1 penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cells at passage number between 10 and 12 were grown to confluence, made serum free for further treatments, and stimulated with PGE2 (1 ng·mL−1) for all the experiments. The human monocytic leukaemia cell line U-937 (ATCC) was maintained in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies) with 10% FBS and 4 mM glutamine. C57BL/6 mouse brain endothelial cells were obtained from Cell Biologics (Chicago, IL, USA) and cultured in Cell Biologics culture complete growth medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Cell Biologics), 0.1% mVEGF, 0.1% heparin, 0.1% rmEGF, 0.1% hydrocortisone, 0.2% ECGS, 1% L-glutamine and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic. All cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Monocyte-endothelial cell adhesion assay

The adherence of U937 cells to activated bEnd.3 cells were examined under static conditions as previously described with minor modifications (Clercka et al., 1994). Briefly, U937 cells were labelled with 10 μM of CellTracker™ Orange (Invitrogen) in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS at 37°C for 1 h and subsequently washed three times with Dulbecco's PBS (0.9 mM CaCl2, 2.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 0.49 mM MgCl2, 138 mM NaCl and 8.1 mM Na2HPO4). bEnd.3 cells in 24-well plates were incubated with PGE2 or LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for 24 h and further incubated with CellTracker Orange labelled U937 cells (4 × 105 cells·mL−1) at 37°C for 1 h. Non-adherent leukocytes were removed by gentle washing with PBS and adhered cells were imaged under Axiovert 200 inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA). Adherent fluorescent cells were counted using Image Pro-Plus 4.0 software. Results were plotted as percentage of the control values for all the experiments.

Reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using Easy-blue kit® (Intron, Seoul, Korea) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Aliquots of total RNA (1 μg) were transcribed using M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Primer sequences were as follows: ICAM-1, sense, 5′-GTC TGC TGA GAC CCC TCT TG-3′, antisense, 5′-GAA GGT GGT TCT TCT GAG CG-3′; GAPDH, sense, 5′-GTG AAG GTC GGT GTG AAC TTT-3′, antisense, 5′-CAC AGT CTT CTG AGT GGC AGT GAT-3′. PCR amplification of the resulting cDNA template was conducted using the following conditions: ICAM-1; 30 cycles of denaturing at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 58.7°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min; GAPDH; 25 cycles of denaturing at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. Reaction products were then separated on a 2% agarose gel and photographed under ultraviolet light. The optical density was determined by a Gel doc system (GEL DOC 2000, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Real-time quantitative PCR for EP receptors

mRNA levels of EP receptor subtypes were determined by real-time PCR and expressed relative to the expression of GAPDH. Purified total RNA (4 μg) were reverse-transcribed using M-MuLV reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The sequences of EP receptors were amplified using a LightCycler® 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA). GAPDH was used as a reference gene for normalization. Primer sequences were as follows: EP1, sense, 5′-GTG CCA AGG GTG GTC CAA-3′, antisense, 5′-AAC CAC TGT GCC GGG AAC TA-3′; EP2, sense, 5′-ATC ACC TTC GCC ATA TGC TC-3′, antisense, 5′-GGT GGC CTA AGT ATG GCA AA-3′; EP3, sense, 5′-GCT GTC CGT CTG TTG GTC-3′, antisense, 5′-CCT TCT CCT TTC CCA TCT G-3′; EP4, sense, 5′-TCA TCT TACT CA TCG CC ACCT-3′, antisense, 5′-TTC ACC ACG TTT GGC TGA TA-3′ and GAPDH, sense, 5′- CTG CAC CAC CAA CTG CTT AGC-3′, antisense, 5′-CTT CAC CAC CTT CTT GAT GTC-3′. The following experimental protocol entailed 45 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 s; annealing at 60°C (for EP1), 52°C (for EP2), 60°C (for EP3), 60°C (for EP4) or 58°C (for GAPDH) for 20 s; and elongation at 72°C for 10 s (for EP1, EP2, EP3, EP4) or 15 s (for GAPDH). Melting curves were determined to ensure amplification specificity of the PCR products. The quantification data were analyzed with LightCycler software 3.3 (Roche Applied Science).

Immunoblot analysis

Immunoblot analysis was used to determine the expression of ICAM-1 expression and the activation of PI3K/Akt, NF-κB and MAPKs. After treatment, cell lysates were prepared by scraping bEnd.3 cells in the lysis buffer (Tris 50 mM at pH 7.4, 10 mM EDTA, 1% Tween-20, 10 μM leupeptin, and 1 mM phenylmethyl-sulfonyl fluoride) and sonicating for 10–15 s (20-W pulses). Cell lysates containing equal amounts of protein were subjected to a 10% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and subsequently blocked in T-TBS buffer (20 mM Tris buffer; 0.5 M NaCl, 0.5% Tween-20) containing 5% non-fat dried milk. Blots were incubated with anti-ICAM-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), EP1 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), EP4 (Cayman Chemical,), p-IκB-α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), IκB-α (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), IκB kinaseβ (IKKβ; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), p-IKKβ (Ser176/180, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), p-Akt (Thr308, Cell Signaling) or Akt (Cell Signaling). All the antibodies used at a dilution of 1:1000. The membrane was further incubated overnight at 4°C with the horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The blots were visualized using WEST-ZOL® plus chemiluminescence detection kit (Intron).

cAMP measurement

Cellular cAMP was quantified using a cyclic AMP EIA kit from Cayman Chemical. Cells (1 × 105) were plated in 6-well dishes and stimulated with 1 ng·mL−1 PGE2 for indicated time. Following stimulation, cells were lysed in 0.1 M HCl and enzyme immunoassay for cAMP was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. Levels of cAMP were normalized to the protein concentration of the lysate. Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Pull-down assay for Rap1 activity

Cells were incubated with PGE2, dibutyryl cAMP (dbcAMP) or 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-2′-O-methyl adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-Cpt-cAMP) for 15 min and treatment was terminated by washing twice with ice-cold PBS and adding 0.8 mL of a lysis buffer according to the instruction manual of active GTPase pull-down and detection kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Rap1 activity was then assessed by the pulling-down the active form of Rap1 with GST-RalGDS RBD according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Plasmids and transfection

Dominant-negative (DN) and catalytically active (CA) mouse Akt in pUSEs were obtained from Invitrogen Life Technologies. Plasmid for the constitutively active PKA-Cα was gifted from Dr. Haeyoung Suh (Ajou University, Suwon, Korea). Mouse Epac1 siRNA was a pool of five target-specific 19–25 nt siRNAs designed to silence Epac1 gene expression in mouse cells (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The EP1 siRNA (ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool PTGER1; L-042324-00), EP4 siRNA (ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool PTGER4; L-048700-00) and control siRNA (D-001210-01-20) were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA). All constructs for transfection were prepared by Endofree Plasmid Midi kit® (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA, USA). bEnd.3 cells (1 × 105 cells) were transiently transfected in serum-free medium with DNA or siRNA using Lipofectamine™ 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions and treated with different agents and all of them were used for experiment at 48 h after transfection. pcDNA3 vector or control siRNAs (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Dharmacon) was used as a negative control.

Luciferase assay

bEnd.3 cells (5 × 104 cells) were co-transfected with a luciferase reporter construct and a β-galactosidase plasmid for 24 h using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions and treated with different agents (triplicate wells each) for another 12 h. AP-1 and NF-κB binding site (2x)-luciferase reporter constructs were provided by Dr. Joo Yong Lee (Catholic University, Bucheon, Korea). Cells were then lysed by adding 100 μL of lysis buffer, sonicated for 10 s and centrifuged in a tabletop microcentrifuge. An aliquot (20 μL) was mixed with 100 μL of assay reagent (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), vortexed, and read immediately in a TD20/20 luminometer (Turner Biosystems, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The luciferase activity was normalized with β-galactosidase activity and expressed as ratio to the treatment-free control.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were cultured on round coverslips for 2 days in DMEM with 10% FBS. After serum starvation for 24 h, cells were treated with 1 ng·mL−1 PGE2 or 100 μM 8-Cpt-cAMP for 15 min and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. After incubation with blocking solution (0.5% bovine serum albumin in 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 120 mM NaCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 5.4 mM KCl, 1.7 mM MgCl2 and 15 mM glucose) for 30 min, the samples were treated with a polyclonal p65 antibody (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for overnight at 4°C. Samples were further incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. The stained samples were mounted on slide glasses with VECTASHIELD® (VectorLab, Burlingame, CA, USA) and examined with a confocal laser scanning microscope with 488 nm of Ar laser and 543 nm of a long pass emission filter (FV-300, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times and the results were expressed as mean ± SE. The statistical analysis included Student's t-test and a one-way anova followed by Dunnett's test for multiple comparisons. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Chemicals

PGE2, LPS (Escherichia coli O111:B4) and anti-actin antibody were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). LY294002, dbcAMP, 8-Cpt-cAMP, Akt inhibitor VIII, H-89 were obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). N6-Benzoyladenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (N6-Benz-cAMP) was purchased from Biolog Inc (Hayward, CA, USA) and (+)-brefeldin A (Epac inhibitor) was from Merck & Co., Inc. (Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA). Sulprostone, (R)-butaprost (free acid), prostaglandin E1 alcohol (1-OH-PGE1) were purchased from Cayman Chemical. EP receptor specific antagonists, ONO-8713 (EP1), ONO-AE3-240 (EP3) and ONO-AE2-227 (EP4) were generous gifts from ONO Pharmaceutical Co. (Osaka, Japan). Nomenclature of PGE2 receptors follows ‘Guide to Receptors and Channels’ (Alexander et al., 2011).

Results

PGE2 increases ICAM-1 expression and leukocyte-endothelial adhesion

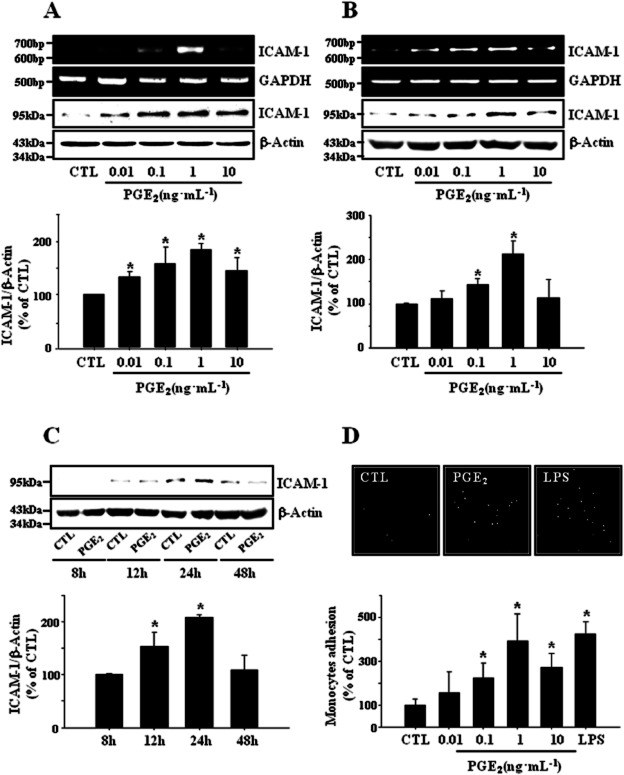

In order to explore the role of PGE2 in the regulation of brain inflammation, we investigated its effects on the expression of ICAM-1 in bEnd.3 cerebrovascular endothelial cells and leukocyte-endothelial cell adhesion. As depicted in Figure 1A, PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression in a dose dependent manner and maximal effect was observed at 1 ng·mL−1. Time course study showed PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression reached to maximum in 24 h and declined to control level in 48 h (Figure 1C). Experiments with primary cultured mouse brain endothelial cells showed qualitatively same results as those obtained from bEnd.3 cells (Figure 1B). Thus, cells were stimulated with 1 ng·mL−1 for 24 h of PGE2 in the subsequent experiments. Exogenous PGE2 dose-dependently increased the adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells and again, maximal effect was observed at 1 ng·mL−1 (Figure 1D). These data indicate that PGE2 plays a role in the regulation of the brain endothelial ICAM-1 expression and leukocyte-endothelial cell adhesion, supporting the previous reports of COX-dependent ICAM-1 expression in the brain cells under various pathological conditions (Stanimirovic et al., 1997; Kyrkanides et al., 2002; Seok et al., 2006).

Figure 1.

PGE2 induces ICAM-1 expression and leukocyte-endothelial adhesion. (A) Murine cerebrovascular endothelial cell line bEnd.3 cells and (B) primary cultured mouse brain endothelial cells were incubated with varying concentrations of PGE2 (0.01∼10 ng·mL−1) for 4 h (RT-PCR) or 24 h (immunoblot). Data are representative of three separate experiments. Values are mean ± SE of protein levels of ICAM-1 relative to β-actin (n = 3). *P < 0.05 compared with control (CTL). (C) bEnd.3 cells were treated with PGE2 (1 ng·mL−1) for indicating time and protein levels of ICAM-1 were determined by immunoblot. Data are representative of three separate experiments. Values are mean ± SE of protein levels of ICAM-1 relative to β-actin (n = 3). *P < 0.05 CTL. (D) PGE2 stimulated adherence of U937 monocytes to bEnd.3 brain endothelial cells. bEnd.3 cells were treated with varying concentrations of PGE2 (0.01∼10 ng·mL−1) or 1 μg·mL−1 LPS for 24 h and further incubated with CellTracker™ Orange prelabelled U937 cells (4 × 105 cells·mL−1) at 37°C for 1 h. Adhered monocytes were imaged under Axiovert 200 inverted microscope. Data are presented as mean ± SE of three independent measurements. *P < 0.05 compared with control.

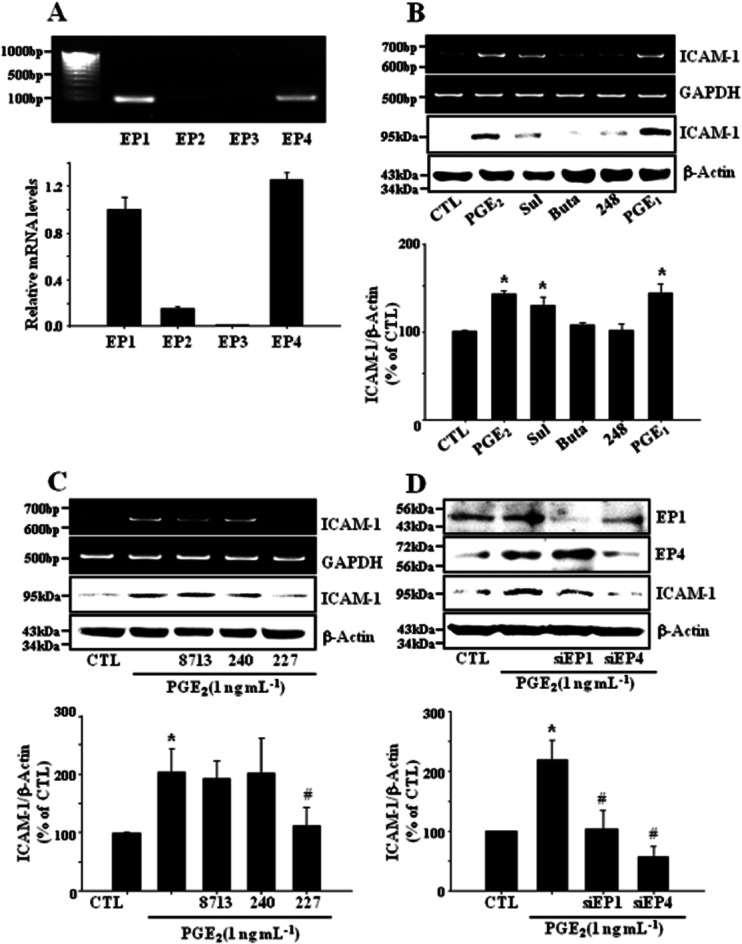

EP4 receptor is associated with PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression

To delineate the EP receptors involved in the effect of PGE2 on endothelial ICAM-1 expression, we examined the expression of EP receptor subtypes and the effects of EP receptor-selective agonists and antagonists on ICAM-1 expression in bEnd.3 cells. Real-time PCR analysis showed that EP1 and EP4 receptors were strongly expressed in these cells while EP3 receptors were barely detected (Figure 2A). PGE2 as well as sulprostone, an EP1/3 agonist, and 1-OH-PGE1, an EP4 selective agonist, induced the expression of ICAM-1 expression, whereas butaprost, an EP2 agonist, and ONO-AE-248, an EP3 selective agonist did not show any significant effect (Figure 2B). Among EP receptor subtype selective antagonists, only ONO-AE2-227 (EP4 antagonist) significantly reduced PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression (Figure 2C). PGE2-stimulation of ICAM-1 expression was blocked by knock-down of EP1 and EP4 with siRNA (Figure 2D). These findings suggest that EP1 and EP4 receptors are associated with the effect of PGE2 on ICAM-1 expression in bEnd.3 brain endothelial cells.

Figure 2.

EP1 and EP4 receptors are associated with PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression. (A) Expression of EP receptor subtypes in bEnd.3 cells. Cells (1 × 105 cells·mL−1) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 100 U·mL−1 penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C for 24 h, and total RNA was extracted, and subjected to real-time PCR for EP1, EP2, EP3 and EP4 mRNA using the respective primers as described in Methods. Amplicons for each EP receptor were obtained with correct size. Values represent the mean ± SE of mRNA levels of the genes relative to murine GAPDH expression (n = 3). (B) Cells were treated with EP receptor subtype selective agonists sulprostone (Sul; EP1/3, 1 nM), butaprost (Buta; EP2, 1 μM), ONO-AE-248 (248; EP3, 1 μM) or 1-OH-PGE1 (PGE1; EP2/4, 1 μM) for 4 h (for RT-PCR) or 24 h (for immunoblot). Data are representative of four separate experiments. Values are mean ± SE of protein levels of ICAM-1 relative to β-actin (n = 4). *P < 0.05 compared with control (CTL). (C) Cells were incubated with selective EP antagonists (EP1: ONO-8713, 10 μM; EP3: ONO-AE3-240, 10 μM; EP4: ONO-AE2-227, 10 μM) in the presence of PGE2 (1 ng·mL−1) for 4 h (for RT-PCR) or 24 h (for immunoblot). Data are representative of four independent experiments. Values are mean ± SE of protein levels of ICAM-1 relative to β-actin (n = 4). *P < 0.05 CTL, #P < 0.05 compared with PGE2 alone. (D) EP1 and EP4 receptors were deleted with siRNA as described in Methods. The levels of EP1, EP4 and ICAM-1 proteins were determined by immunoblot at 24 h. Data are representative of four independent experiments. Values are mean ± SE of protein levels of ICAM-1 relative to β-actin (n = 4). *P < 0.05 compared with control (CTL), #P < 0.05 compared with PGE2 alone.

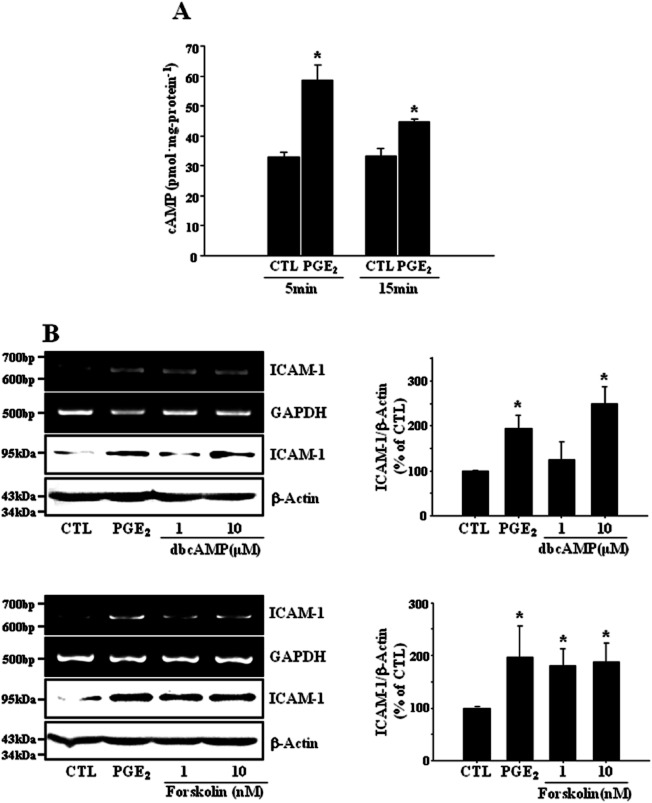

cAMP mediates PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression

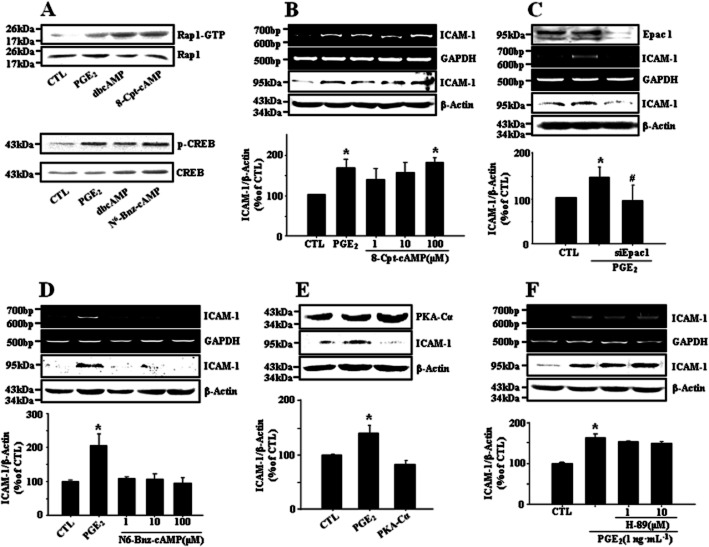

It is well known that the EP4 receptor is positively coupled to cAMP production. We also observed that cellular level of cAMP was increased in bEnd.3 endothelial cells exposed to PGE2 (Figure 3A, 32.9 ± 1.6 and 58.7 ± 5.0 pmol·mg−1 protein in control and PGE2 at 5 min, respectively). The effect of PGE2 on ICAM-1 expression was mimicked by the cAMP analog dbcAMP as well as the adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin (Figure 3B), indicating the mediation of PGE2 action by cAMP. PGE2 activated two key receptors for cAMP, protein kinase A (PKA) and exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (Epac) as assessed by cAMP response element-binding (CREB) phosphorylation and Rap1-GTP formation (Figure 4A). 8-Cpt-cAMP, an Epac specific activator induced ICAM-1 expression and a knock-down of Epac1 with siRNA resulted in the elimination of PGE2 effect on ICAM-1 expression (Figure 4B,C). In addition, brefeldin A, an Epac inhibitor diminished PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression (data are not shown). In contrast, neither a PKA specific activator N6-Bnz-cAMP, nor a PKA inhibitor H-89 affected ICAM-1 expression (Figure 4D,F). Furthermore, transient expression of catalytically active PKA-Cα did not elicit any significant effect on ICAM-1 expression (Figure 4E). These findings suggest cAMP mediates PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression via activation of Epac-Rap1 pathway.

Figure 3.

cAMP mediates PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression. (A) PGE2 increases cAMP levels in bEnd.3 cells. Cells (1 × 105 cells·mL−1) were treated with PGE2 (1 ng·mL−1) for indicated times, then cellular cAMP levels were measured as described in Methods. Data (mean ± SE of three separate measurements) are expressed as pmoles of cAMP·mg-protein−1. *P < 0.05 compared with time matched control (CTL). (B) bEnd.3 cells were incubated with dibutyryl cAMP (dbcAMP, 1 and 10 μM) or forskolin (1 and 10 nM). The levels of ICAM-1 mRNA and protein were determined by RT-PCR and immunoblot at 4 h and 24 h, respectively. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Values are mean ± SE of protein levels of ICAM-1 relative to β-actin (n = 3). *P < 0.05 compared with control (CTL), #P < 0.05 compared with PGE2 alone.

Figure 4.

Epac but not protein kinase A mediates PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression in bEnd.3 cells. (A) PGE2 activates two key receptors for cAMP, PKA and Epac as assessed by CREB phosphorylation and Rap1-GTP formation. Cells were treated with PGE2 (1 ng·mL−1), dbcAMP (10 μM), 8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-2′-O-methyl adenosine 3′5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-Cpt-cAMP, 100 μM), an Epac activator or N6-benzoyladensine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (N6-Bnz-cAMP, 100 μM), a PKA activator for 15 min. Rap1-GTP formation was assessed by pulling down the active form of Rap1 with GST-RalGDS RBD as described in Methods. CREB phosphorylation was determined by immunoblot. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (B, C) Epac mediates PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression in bEnd.3 cells. Cells were treated with PGE2 (1 ng·mL−1) or 8-Cpt-cAMP (1∼100 μM). In a separate experiment, Epac1 was deleted with siRNA for Epac1 as described in Methods. The levels of ICAM-1 mRNA and protein were determined by RT-PCR and immunoblot at 4 h and 24 h, respectively. Data are representative of four independent experiments. Values are mean ± SE of protein levels of ICAM-1 relative to β-actin (n = 4). *P < 0.05 compared with control (CTL), #P < 0.05 compared with PGE2 alone. (D–F) PKA appears not involved in PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression. Cells were treated with N6-Bnz-cAMP (1∼100 μM) alone or H89 (1∼10 μM), a PKA inhibitor in the presence of PGE2 (1 ng·mL−1). In a separate experiment, PKA-Cα, a catalytically active form of PKA, was transiently transfected as described in Methods. The levels of ICAM-1 mRNA and protein were determined by RT-PCR and immunoblot at 4 h and 24 h, respectively. Data are representative of three independent experiments. Values are mean ± SE of protein levels of ICAM-1 relative to β-actin (n = 3). *P < 0.05 compared with control (CTL).

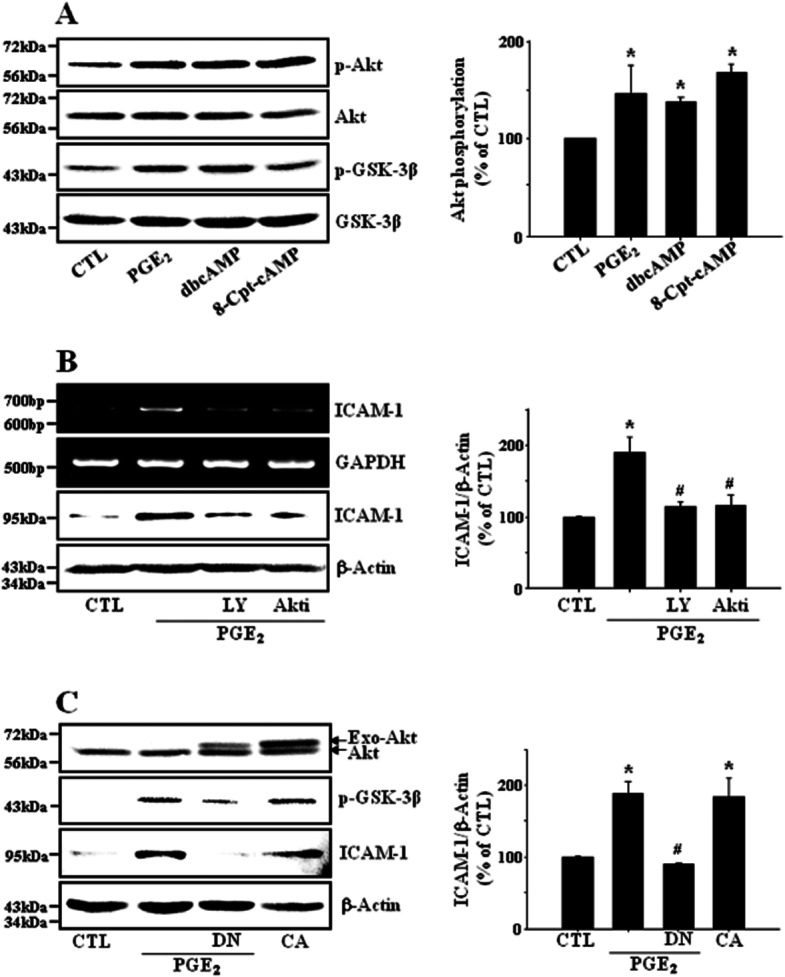

PI3K/Akt signalling pathway is involved in PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression

To explore the downstream signalling of Epac/Rap1, possible involvement of PI3K/Akt pathway was examined. As shown in Figure 5A, PGE2, dbcAMP and 8-Cpt-cAMP stimulated the phosphorylation of Akt and GSK-3β (downstream targets of PI3K and Akt, respectively). LY294002, a PI3K inhibitor and Akti, an Akt inhibitor suppressed PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression (Figure 5B). Transient expression of CA Akt increased the level of ICAM-1 protein in the absence of PGE2 and transfection of DN Akt construct resulted in the reduction of ICAM-1 expression during PGE2 challenge (Figure 5C). Transfected DN and CA Akt successfully regulated the phosphorylation of GSK-3β, a downstream target of Akt, under our experimental condition (Figure 5C). These data indicate that PI3K/Akt signalling pathway is involved in PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression.

Figure 5.

Epac-mediated signalling proceeds through PI3K and Akt. (A) The activation of Epac increases the phosphorylation of Akt. bEnd.3 cells were treated with PGE2 (1 ng·mL−1), dbcAMP (10 μM) or 8-Cpt-cAMP (100 μM) for 15 min and phosphorylation levels of Akt and GSK-3β were evaluated with immunoblot analysis. Data are representative of four independent experiments. Values are mean ± SE of levels of phosphorylated Akt relative to total Akt (n = 4). *P < 0.05 compared with control (CTL). (B) PI3K/Akt signalling pathway is involved in PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression. Cell were pretreated with LY294002 (LY, 10 μM) or Akt inhibitor VIII (Akti, 100 nM) for 30 min and further incubated with PGE2 (1 ng·mL−1) for 4 h (RT-PCR) or 24 h (immunoblot). Data are representative of three independent experiments. Values are mean ± SE of protein levels of ICAM-1 relative to β-actin (n = 3). *P < 0.05 compared with control (CTL), #P < 0.05 compared with PGE2 alone. (C) Cell were transfected with pcDNA3 control vectors (CTL), dominant-negative (DN) Akt or catalytically active (CA) Akt construct using Lipofectamine™. After 36 h, transfected cell were treated with PGE2 (1 ng·mL−1) for another 12 h and cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting. Data are representative of four independent experiments. Values are mean ± SE of protein levels of ICAM-1 relative to β-actin (n = 4). *P < 0.05 compared with control (CTL), #P < 0.05 compared with PGE2 alone.

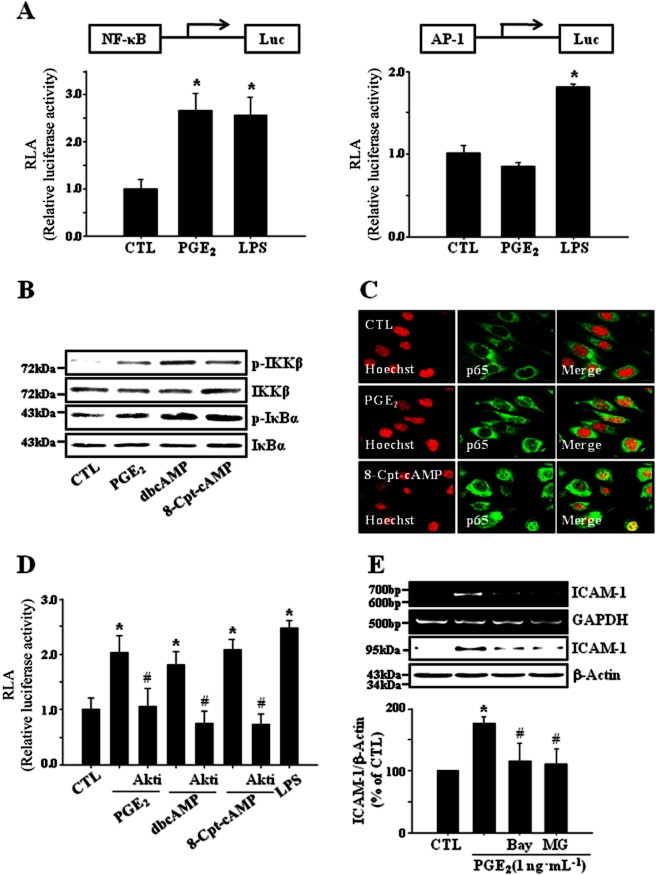

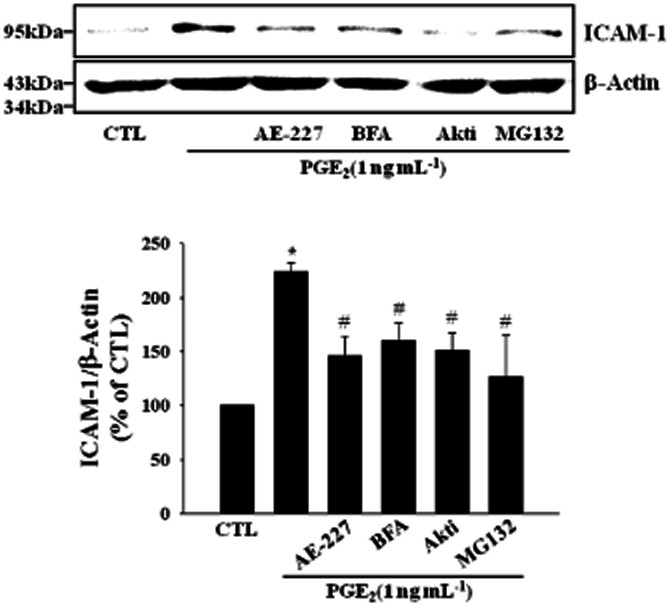

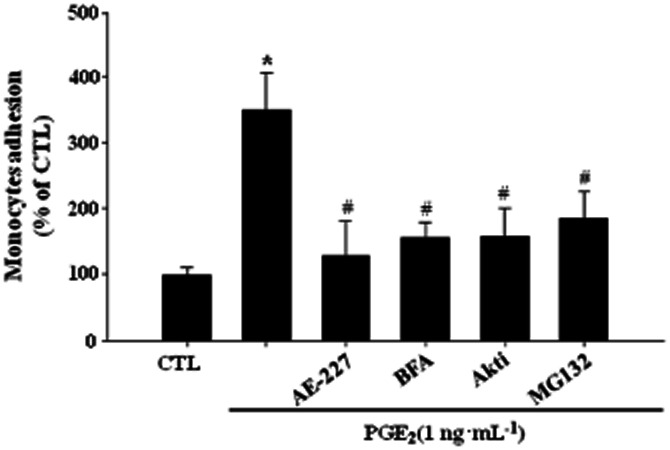

The activation of NF-κB is a major component in PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression

Transcription factors such as NF-κB and AP-1 are known to bind to κB and TRE consensus sequences separately to regulate ICAM-1 gene expression (Chen and Han, 2001). To assess the effects of PGE2 on transcriptional activities of NF-κB and AP-1, NF-κB and AP-1-specific reporter assays were adopted. PGE2 increased the transcriptional activity of NF-κB whereas it did not elicit any significant effect in AP-1 reporter assay (Figure 6A). PGE2 induced the phosphorylation of IKKβ and IκBα (Figure 6B) and stimulated the translocation of p65 to the nucleus (Figure 6C), supporting the activation of NF-κB by PGE2. dbcAMP and Epac activator (8-Cpt-cAMP) also showed similar effects (Figure 6B,C). dbcAMP and 8-Cpt-cAMP increased NF-κB activity in a reporter assay, which was significantly suppressed by Akti, an Akt inhibitor (Figure 6D). NF-κB inhibitors, Bay-11–7082 and MG-132 diminished PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression (Figure 6E). These results suggest that cAMP/Epac-mediated signalling proceeds through PI3K, Akt and NF-κB and finally leads to the expression of ICAM-1 in bEnd.3 brain endothelial cells exposed to PGE2. In primary cultured mouse brain endothelial cells, PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression was significantly attenuated by the treatment of ONO-AE2-227 (an EP4 antagonist), brefeldin A (an Epac inhibitor), Akti (an Akt inhibitor) or MG132 (an IkBα degradation inhibitor), confirming the results obtained from bEnd.3 brain endothelial cells (Figure 7). A functional relevance of this molecular signalling was illustrated in a leukocyte adhesion assay, in which PGE2-induced promotion of leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cells was eliminated by the treatment of ONO-AE2-227, brefeldin A, Akti or MG-132 (Figure 8).

Figure 6.

NF-κB activation is a major component in PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression. (A) PGE2 increases the transcriptional activity of NF-κB but not AP-1 in bEnd.3 cells. Cells were transfected with NF-κB or AP-1 binding site (2x)-luciferase reporter plasmid for 24 h and further incubated with PGE2 (1 ng·mL−1) or LPS (1 μg·mL−1) for 12 h. Luciferase activities were measured as described in Methods and relative luciferase activity (RLA) was normalized with β-galactosidase activity. Data are presented as mean ± SE of three independent measurements. *P < 0.01 compared with control (CTL). (B) PGE2-cAMP-Epac signaling axis induces the activation of NF-κB through IKKβ phosphorylation. bEnd.3 cells were exposed to PGE2 (1 ng·mL−1), dbcAMP (10 μM) or 8-Cpt-cAMP (100 μM) for 15 min and the phosphorylation of IKKβ and IκBα was assessed by immunoblot. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (C) PGE2 and 8-Cpt-cAMP stimulate the translocation of p65 to the nucleus. Cells were exposed to PGE2 (1 ng·mL−1) or 8-Cpt-cAMP (100 μM) for 15 min and the translocation of p65 was determined by immunocytochemistry (green, Alexa Fluor 488; red, Hoechst 33258). Data are representative of three independent experiments. (D) Akti, an Akt inhibitor diminishes NF-κB dependent reporter gene activity induced by PGE2, dbcAMP and 8-Cpt-AMP. Cells were transfected with NF-κB binding site (2x)-luciferase reporter plasmid for 24 h. Transfected cells were pretreated with Akti (100 nM) for 30 min and incubated with PGE2 (1 ng·mL−1), dbcAMP (10 μM), or 8-Cpt-cAMP (100 μM) for another 12 h. Data are presented as mean ± SE of three independent measurements. *P < 0.05 compared with control (CTL), #P < 0.05 compared with PGE2, dbcAMP and 8-Cpt-cAMP alone. (E) NF-κB inhibitors reduce PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression. Cells were incubated with PGE2 (1 ng·mL−1) in the presence of NF-κB inhibitors such as MG132 (an IκBα degradation inhibitor, 10 μM) and Bay11-7082 (an IκBα phosphorylation inhibitor, 5 μM). The levels of ICAM-1 mRNA and protein were determined by RT-PCR and immunoblot at 4 h and 24 h, respectively. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Figure 7.

PGE2 induces ICAM-1 expression via EP4 receptor and Epac/Akt/NF-kB signaling pathway in primary cultured mouse brain endothelial cells. Cells were treated with ONO-AE2-227 (AE-227, an EP4 antagonist, 10 μM), brefeldin A (BFA, an Epac inhibitor, 10 μM), Akti (100 nM) or MG132 (10 μM) in the presence of PGE2 (1 ng·mL−1) for 24 h and protein levels of ICAM-1 were determined by immunoblot. Data are representative of four separate experiments. Values are mean ± SE of protein levels of ICAM-1 relative to β-actin (n = 4). *P < 0.05 compared with control (CTL), #P < 0.05 compared with PGE2 alone.

Figure 8.

PGE2 enhances leukocyte adhesion via EP4 receptor and Epac/Akt/NF-kB signaling pathway in bEnd.3 cells. Cells were treated with ONO-AE2-227 (AE-227, an EP4 antagonist, 10 μM), brefeldin A (BFA, an Epac inhibitor, 10 μM), Akti (100 nM) or MG132 (10 μM) in the presence of PGE2 (1 ng·mL−1) for 24 h and further incubated with CellTracker™ Orange prelabelled U937 cells (4 × 105 cells·mL−1) at 37°C for 1 h. Adhered monocyte cells were imaged under Axiovert 200 inverted microscope. Data are presented as mean ± SE of three independent measurements. *P < 0.05 compared with control (CTL), #P < 0.05 compared with PGE2 alone.

Discussion and conclusion

PGE2 is known to exert divergent modulatory action on the inflammatory responses depending on types of cell and stimulus. The diversity and specificity of cellular effects of PGE2 are believed to be dependent on cell surface expression of four functionally distinct subtypes of PGE2 receptors. We found that EP1 and EP4 receptors are strongly expressed in bEnd.3 cells (Figure 2A). Intriguingly, among subtype specific antagonists, only EP4 selective antagonist (ONO-AE2-227) significantly suppressed PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression, suggesting the EP4 mediation of PGE2 effect. This result was further supported by knock-down of EP4 with siRNA (Figure 2D). It is well known that PGE2 binds to EP receptors with differential affinities (Milatovic et al., 2011). In mice, PGE2 binding affinities are as follows: EP3 (Kd = 0.9 nM) > EP4 (Kd = 1.9 nM) > EP2 (Kd = 12 nM) > EP1 (Kd = 20 nM). In the present study, cells were treated with PGE2 at 1 ng·mL−1 (= 2.8 nM). Thus, it is likely that PGE2 preferentially bound to EP4 under our experimental condition. EP4 receptor has been demonstrated to be coupled to a Gs protein, adenylyl cyclase activation, and cAMP production (Sugimoto and Narumiya, 2007). We also found that PGE2 increased the cellular level of cAMP in bEnd.3 cells and dbcAMP and forskolin, a cAMP elevating agent, mimicked the effects of PGE2 on ICAM-1 expression. These results further support the implication of EP4 receptor in PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression.

cAMP is known to play a regulatory role in leukocyte adhesion to endothelium and transendothelial migration during inflammation. However, the effect of cAMP on cell adhesion remains controversial (Zeidler et al., 2000; Lorenowicz et al., 2006). This discrepancy has been attributed to the complexity of cAMP-driven signalling. Actions of cAMP are mediated by a variety of cAMP effector proteins such as PKA, Epac, PDZ-GEF and cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Among these, PKA and Epac are two major targets of cAMP, which have been implicated in the regulation of leukocyte transendothelial migration and endothelial barrier function (Lorenowicz et al., 2007). Recently, it was reported that cAMP/Epac pathway might be involved in acidosis-induced endothelial cell adhesion and ICAM-1 expression (Chen et al., 2011). It was also shown that Epac specific activators completely reversed thromboxane receptor antagonist-induced reduction of ICAM-1 expression in human coronary artery endothelial cells (Sand et al., 2010). In contrast, the prime cAMP effector PKA was reported to have both negative and positive role in the regulation of ICAM-1 expression depending on the types of cAMP-inducing stimuli (Bernot et al., 2005; Yoshimoto et al., 2005). In this study, we demonstrated that PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression was mimicked by 8-Cpt-cAMP, an Epac specific activator, and suppressed by knock-down of Epac1 (Figure 4). However, these results were not reproduced by the manipulation of PKA activity, indicating the implication of Epac rather than PKA in the PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression in cerebrovascular endothelial cells. Often, both cAMP targets are associated with the same biological process, in which they fulfil either opposite or synergistic effects (Gloerich and Bos, 2010). However, our data suggest the lack of interaction between these two signalling pathways under our experimental condition.

Epac proteins are reported to exert diverse biological functions by signalling to a wide range of effectors such as ERKs, PKB/Akt, NF-κB and GSK-3β. These signalling molecules have been implicated in the inflammatory responses including ICAM-1 expression in vascular endothelial cells (Radisavljevic et al., 2000; Minhajuddin et al., 2009; Fan et al., 2010). However, we observed that specific inhibitors of MAPKs did not affect PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression in brain endothelial cells (Data are not shown). In contrast, PGE2 effect was significantly attenuated by specific inhibitors of PI3K and Akt (Figure 5). These results were supported by data obtained from a DN and constitutively active mutant of Akt. Akt phosphorylation was stimulated by PGE2, of which effect was mimicked by dbcAMP and Epac activator. Taken together, our data indicate that Epac-mediated signalling proceeds through PI3K and Akt in PGE2-stimulated brain endothelial cells. Roles of PI3K/Akt pathway in endothelial ICAM-1 expression under various pathological conditions have been documented (Radisavljevic et al., 2000; Hur et al., 2007; Minhajuddin et al., 2009; Dagia et al., 2010). However, until this time, there is no report describing the involvement of PI3K/Akt pathway in PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression. To our knowledge, our study is the first to demonstrate a regulatory link between activation of Epac/PI3K/Akt and up-regulation of ICAM-1 in brain endothelial cells exposed to PGE2.

NF-κB activation has been implicated in pro-inflammatory stimuli-triggered endothelial ICAM-1 expression (Balyasnikova et al., 2000; Rahman et al., 2004; Minhajuddin et al., 2009). In the present study, we found that PGE2 induced sequential events for NF-κB activation, that is, phosphorylation of IκBβ kinase and IκBα, translocation of p65 to nucleus and increase in NF-κB reporter gene activity (Figure 6). In addition, suppression of NF-κB by Bay-11–7082 and MG-132 attenuated PGE2-induced ICAM-1 expression. These results suggest that NF-κB activation is critically involved in ICAM-1 expression in cerebrovascular endothelial cells stimulated with PGE2. Moreover, Akt inhibitor diminished NF-κB dependent reporter gene activity induced by PGE2, dbcAMP and Epac activator, indicating roles of cAMP, Epac and Akt in PGE2-induced NF-κB activation. These findings are consistent with previous reports that PI3K/Akt modulates NF-κB activation and ICAM-1 expression in endothelial cells (Rahman et al., 2002; Minhajuddin et al., 2009). cAMP is known to exert differential effects on NF-κB activity in a cell type- and stimulus-specific manner. Although most studies report the inhibition of NF-κB activity by cAMP-inducing stimuli, other papers have shown that cAMP stimulates NF-κB activity or does not interfere with NF-κB activation (Gerlo et al., 2011). Overwhelming reports have shown that prototypical cAMP effector PKA is implicated in either inhibitory or stimulatory modulation of NF-κB activity by cAMP effects. However, recent papers showed that the positive effect on NF-κB was not mediated by PKA, but was dependent on Epac activation in murine macrophages (Moon and Pyo, 2007; Moon et al., 2011). We also observed Epac-mediated NF-κB activation in cerebrovascular endothelial cells. These results suggest that Epac-mediated Akt/NF-κB pathway could be helpful for interpretation on various cAMP-mediated physiological responses. Indeed, it was postulated that differential effects of cAMP on NF-κB might be the result of preferential activation of PKA or Epac (Gerlo et al., 2011). Likewise, our findings could provide an insight into explaining contradictory results in PGE2 effect on ICAM-1 expression in a variety of cells.

PGE2 is involved in all processes leading to the classic signs of inflammation (Funk, 2001). Thus, PGE2 has been referred to as a classic pro-inflammatory mediator. The relevance of PGE2 during promotion of inflammation is supported by the effectiveness of NSAIDs (Simmons et al., 2004). However, accumulating evidences indicate that PGE2 can also exert anti-inflammatory effects in the CNS (Milatovic et al., 2011). PGE2 is reported to inhibit LPS-induced microglial activation and cytokine gene expression (Levi et al., 1998; Caggiano and Kraig, 1999) and stimulate production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (Aloisi et al., 1999). Intriguingly, recent studies in microglia and peripheral macrophages suggest that EP4 signalling mediates anti-inflammatory effects of PGE2 and this is associated with PKA activation, reduction of Akt and IκB kinase phosphorylation and decreased nuclear translocation of p65 and p50 NF-κB subunits (Shi et al., 2010). Moreover, the prostanoid PGE1, an EP4 agonist, blocks induction of ICAM-1 expression in various models of inflammation (Takahashi et al., 2003; 2005). These findings support a potential anti-inflammatory role of EP4 in brain diseases characterized by an inflammatory response. However, in the present study, we demonstrated that PGE2 signalling via EP4 receptor elicited inflammatory response in terms of endothelial ICAM-1 expression, and signalling pathways therein involved were distinct from those in microglia and macrophages. These results indicate that EP receptors could mediate pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory effects depending on the cell types in which they are expressed. At present, it is unclear what caused differences in PGE2 effect and participating signalling cascade, but these may include the injury context including the type, duration and strength of stimulus as well as cell types involved, expressing a specific repertoire of PGE2- or cAMP-responsive effectors (Lorenowicz et al., 2007; Andreasson, 2010). Thus, comparative study on these factors would contribute to better understanding of roles of PGE2 in brain inflammation.

In summary, our data obtained in the current study indicate that PGE2 up-regulates endothelial ICAM-1 expression through ligation of EP4 receptor and sequential activation of Epac-Rap1, PI3K/Akt and NF-κB, and thereby induces leukocyte adhesion to brain endothelial cells. These findings imply the role of PGE2 and cAMP-controlled signalling pathway in a variety of inflammatory CNS injury, although additional in vivo studies are needed to address the functional significance of results.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from of Department of Medical Sciences, The Graduate School, Ajou University and a grant from of the GRRC Program of Gyunggi-Do, Republic of Korea through the Center for Cell Death Regulating Biodrug, Ajou University, Republic of Korea.

Glossary

- 1-OH-PGE1

prostaglandin E1 alcohol

- 8-Cpt-cAMP

8-(4-chlorophenylthio)-2′-O-methyl adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate

- Akti

Akt inhibitor VIII

- CNS

central nervous system

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- CREB

cAMP response element-binding

- dbcAMP

dibutyryl cAMP

- EP receptors

E-prostanoid receptors

- Epac

exchange protein activated by cAMP

- GSK-3β

glycogen synthase kinase-3β

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- IKKβ

IκB kinaseβ

- MAPKs

mitogen-activated protein kinases

- N6-Bnz-cAMP

N6-benzoyladenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodesyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

Conflicts of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Aid S, Bosetti F. Targeting cyclooxygenases-1 and -2 in neuroinflammation: therapeutic implications. Biochimie. 2011;93:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aktan S, Aykut C, Oktay S, Yegen B, Keles E, Aykac I, et al. The alterations of leukotriene C4 and prostaglandin E2 levels following different ischemic periods in rat brain tissue. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1991;42:67–71. doi: 10.1016/0952-3278(91)90069-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to receptors and channels (GRAC) Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164(Suppl. 1):S1–S324. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01649_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloisi F, De Simone R, Columba-Cabezas S, Levi G. Opposite effects of interferon-gamma and prostaglandin E2 on tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-10 production in microglial: a regulatory loop controlling microglia pro- and anti-inflammatory activities. J Neurosci Res. 1999;56:571–580. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990615)56:6<571::AID-JNR3>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasson K. Emerging roles of PGE2 receptors in models of neurological disease. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2010;91:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam TV, Woodruff TM, Lathia JD, Selvaraj PK, Mattson MP, Taylor SM. Neuroprotection in stroke by complement inhibition and immunoglobulin therapy. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1074–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balyasnikova IV, Pelligrino DA, Greenwood J, Adamson P, Dragon S, Raza H, et al. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate regulates the expression of the intercellular adhesion molecule and the inducible nitric oxide synthase in brain endothelial cells. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:688–699. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200004000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernot D, Peiretti F, Canault M, Juhan-Vague I, Nalbone G. Upregulation of TNF-alpha-induced ICAM-1 surface expression by adenylate cyclase-dependent pathway in human endothelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 2005;202:434–441. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop-Bailey D, Burke-Gaffney A, Hellewell PG, Pepper JR, Mitchell JA. Cyclo-oxygenase-2 regulates inducible ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;249:44–47. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowes MP, Zivin JA, Rothlein R. Monoclonal antibody to the ICAM-1 adhesion site reduces neurological damage in a rabbit cerebral embolism stroke model. Exp Neurol. 1993;119:215–219. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiano AO, Kraig RP. Prostaglandin E receptor subtypes in cultured rat microglia and their role in reducing lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-1beta production. J Neurochem. 1999;72:565–575. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlos TM, Harlan JM. Leukocyte-endothelial adhesion molecules. Blood. 1994;84:2068–2101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Dong L, Leffler NR, Asch AS, Witte ON, Yang LV. Activation of GPR4 by acidosis increases endothelial cell adhesion through the cAMP/Epac pathway. Plos ONE. 2011;6:e27586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen NG, Han X. Dual function of troglitazone in ICAM-1 gene expression in human vascular endothelium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:717–722. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cimino PJ, Keene CD, Breyer RM, Montine KS, Montine TJ. Therapeutic targets in prostaglandin E2 signaling for neurologic disease. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:1863–1869. doi: 10.2174/092986708785132915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clercka LSD, Bridtsa CH, Mertensa AM, Moensa MM, Stevens WJ. Use of fluorescent dyes in the determination of adherence of human leukocytes to endothelial cells and the effect of fluorechromes on cellular function. J Immunol Methods. 1994;172:115–124. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90384-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagia NM, Aqarwal G, Kamath DV, Chetrapal-Kunwar A, Gupte RD, Jadhav MG, et al. A preferential p110alpha/gamma PI3K inhibitor attenuates experimental inflammation by suppressing the production of proinflammatory mediators in a NF-kappaB-dependent manner. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C929–C941. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00461.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Liu C, Qin X, Wang Y, Han Y, Zhou Y. The role of ERK1/2 signaling pathway in Nef protein upregulation of the expression of the intercellular adhesion molecule 1 in endothelial cells. Angiology. 2010;61:669–678. doi: 10.1177/0003319710364215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk CD. Prostaglandins and leukotrienes: advances in eicosanoid biology. Science. 2001;294:1871–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5548.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlo S, Kooijman R, Beck IM, Kolmus K, Spooren A, Haegeman G. Cyclic AMP: a selective modulator of NF-kB action. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:3823–3841. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0757-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloerich M, Bos JL. Epac: defining a new mechanism of cAMP action. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:355–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur J, Yoon CH, Lee CS, Kim TY, Oh IY, Park KW, et al. Akt is a key modulator of endothelial progenitor cell trafficking in ischemic muscle. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1769–1778. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley SD, Olschowka JA, O'Banion MK. Cyclooxygenase inhibition as a strategy to ameliorate brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2002;19:1–15. doi: 10.1089/089771502753460196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinski P. Regulation of immune responses by prostaglandin E2. J Immunol. 2012;188:21–28. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrkanides S, Moore AH, Olschowka JA, Daeschner JC, Williams JP, Hansen JT, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 modulates brain inflammation-related gene expression in central nervous system radiation injury. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2002;104:159–169. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer HF, Chavakis T. Leukocyte-endothelial interactions in inflammation. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:1211–1220. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00811.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legler DF, Bruckner M, Uetz-von Allmen E, Krause P. Prostaglandin E2 at new glance: novel insights in functional diversity offer therapeutic chances. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:198–201. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi G, Minghetti L, Aloisi F. Regulation of prostanoid synthesis in microglial cells and effects of prostaglandin E2 on microglial functions. Biochimie. 1998;80:899–904. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(00)88886-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenowicz MJ, van Gils J, de Boer M, Hordijk PL, Fernandez-Borja M. Epac1-Rap1 signaling regulates monocyte adhesion and chemotaxis. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:1542–1552. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0506357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenowicz MJ, Fernandez-Borja M, Hordijk PL. cAMP signaling in leukocyte transendothelial migration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1014–1022. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.106.132282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milatovic D, Montine TJ, Aschner M. Prostanoid signaling: dual role for prostaglandin E2 in neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology. 2011;32:312–319. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minghetti L. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in inflammatory and degenerative brain diseases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:901–910. doi: 10.1093/jnen/63.9.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minhajuddin M, Bijli KM, Fazal F, Sassano A, Nakayama KI, Hay N, et al. Protein kinase C-δ and phosphatidylinsitol 3-kinase/Akt activate mammalian target of rapamycin to modulate NF-κB activation and intercellular adhesion molecule-1(ICAM-1) expression in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4052–4061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805032200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon EY, Pyo S. Lipopolysaccharide stimulates Epac1-mediated Rap1/NF-kappaB pathway in RAW264.7 murine macrophages. Immunol Lett. 2007;110:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon EY, Lee JH, Lee JW, Song JH, Pyo S. ROS/Epac1-mediated Rap1/NF-kappaB activation is required for the expression of BAFF in Raw264.7 murine macrophages. Cell Signal. 2011;23:1479–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi K, Iwasaki K, Shitashige M, Umeda M, Izumi Y, Murota S, et al. Downregulation of lipopolysaccaride-induced intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression via EP2/EP4 receptors by prostaglandin E2 in human fibroblasts. Inflammation. 2001;25:75–81. doi: 10.1023/a:1007110304044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radisavljevic Z, Avraham H, Avraham S. Vascular endothelial growth factor up-regulates ICAM-1 expression via the phosphatidylinositol 3 OH-kinase/AKT/Nitric oxide pathway and modulates migration of brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20770–20774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002448200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, True AL, Anwar KN, Ye RD, Voyno-Yasenetskaya TA, Malik AB. Galpha(q) and Gbetagamma regulate PAR-1 signaling of thrombin-induced NF-kappaB activation and ICAM-1 transcription in endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2002;91:398–405. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000033520.95242.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Anwar KN, Minhajuddin M, Bijli KM, Javaid K, True AL, et al. cAMP targeting of p38 MAP kinase inhibits thrombin-induced NF-kappaB activation and ICAM-1 expression in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287:L1017–L1024. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00072.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi B, Angiari S, Zenaro E, Budui SL, Constantin G. Vascular inflammation in central nervous system diseases: adhesion receptors controlling leukocyte-endothelial interactions. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89:539–556. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0710432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sand C, Grandoch M, Borgermann C, Oude Weernink PA, Mahlke Y, Schwindenhammer B, et al. 8-pCPT-conjugated cyclic AMP analogs exert thromboxane receptor antagonistic properties. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:662–678. doi: 10.1160/TH09-06-0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seok SM, Park DH, Kim YC, Moon CH, Jung YS, Baik EJ, et al. COX-2 is associated with cadmium-induced ICAM-1 expression in cerebrovascular endothelial cells. Toxicol Lett. 2006;165:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Johansson J, Woodling NS, Wang Q, Montine TJ, Andreasson K. The prostaglandin E2 E-prostanoid 4 receptor exerts anti-inflammatory effects in brain innate immunity. J Immunol. 2010;184:7207–7218. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons DL, Botting RM, Hla T. Cyclooxygenase isozymes: the biology of prostaglandin synthesis and inhibition. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56:387–437. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer TA. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell. 1994;76:301–314. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanimirovic D, Shapiro A, Wong J, Hutchison J, Durkin J. The induction of ICAM-1 in human cerebromicrovascular endothelial cells (HCEC) by ischemia-like conditions promotes enhanced neutrophil/HCEC adhesion. J Neuroimmunol. 1997;76:193–205. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(97)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto Y, Narumiya S. Prostaglandin E receptors. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11613–11617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600038200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi HK, Iwagaki H, Tamura R, Xue D, Sano M, Mori S, et al. Unique regulation profile of prostaglandin e1 on adhesion molecule expression and cytokine production in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:1188–1195. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.056432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi HK, Xue D, Iwagaki H, Tamura R, Katsuno G, Yagi T, et al. Prostaglandin E1-initiated immune regulation during human mixed lymphocyte reaction. Clin Immunol. 2005;115:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vemuganti R, Dempsey RJ, Bowen KK. Inhibition of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 protein expression by antisense oligonucleotides is neuroprotective after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in rat. Stroke. 2004;35:179–184. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000106479.53235.3E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler M, Kemp B, Hauptmann S, Rath W. Parturition: steroids, prostaglandin E2, and expression of adhesion molecules by endothelial cells. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:398–402. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(96)00500-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SF, Chen MK, Hsieh YS, Chung TT, Hsieh YH, Lin CW, et al. Prostaglandin E2/EP1 signaling pathway enhances intercellular adhesion molecule 1(ICAM-1) expression and cell motility in oral cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:29808–29816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.108183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto T, Gochou N, Fukai N, Sugiyama T, Shichiri M, Hirata Y. Adrenomedullin inhibits angiotension II-induced oxidative stress and gene expression in rat endothelial cells. Hypertens Res. 2005;28:165–172. doi: 10.1291/hypres.28.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidler R, Csanady M, Gires O, Lang S, Schmitt B, Wollenberg B. Tumor cell-derived prostaglandin E2 inhibits monocyte function by interfering with CCR5 and Mac-1. FASEB J. 2000;14:661–668. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.5.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]