Abstract

Functional genomics have not been reported for Opisthorchis viverrini or the related fish-borne fluke, Clonorchis sinensis. Here we describe the introduction by square wave electroporation of Cy3-labelled small RNA into adult O. viverrini worms. Adult flukes were subjected to square wave electroporation employing a single pulse for 20 ms of 125 volts in the presence of 50 μg/ml of Cy3-siRNA. The parasites tolerated this manipulation and, at 24 and 48 hours after electroporation, fluorescence from the Cy3-siRNA was evident throughout the parenchyma of the worms, with strong fluorescence evident in the guts and reproductive organs of the adult worms. Second, other worms were treated using the same electroporation settings with double stranded RNA targeting an endogenous papain-like cysteine protease, cathepsin B. This manipulation resulted in a significant reduction in specific mRNA levels encoding cathepsin B, and a significant reduction in cathepsin B activity against the diagnostic peptide, Z-Arg-Arg-AMC. This appears to be the first report of introduction of reporter genes into O. viverrini and the first report of experimental RNA interference (RNAi) in this fluke. The findings indicated the presence of an intact RNAi pathway in these parasites which, in turn, provides an opportunity to probe gene functions in this neglected tropical disease pathogen.

Keywords: O. viverrini, RNA interference, cathepsin B, liver fluke

1. Introduction

The mechanisms by which infection with Opisthorchis viverrini causes cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), cancer of the bile ducts, are likely to be multi-factorial [1]. The liver fluke induces inflammation of the bile ducts, resulting in oxidative DNA damage of the epithelium. In addition, the flukes secrete proteins that promote biliary epithelial cells to hyper-proliferate but not undergo apoptosis, providing an additional potential mechanism by which epithelial cells become malignant [2]. Characterization of these secreted antigens may give important information about the key molecules responsible for O. viverrini-associated CCA pathogenesis [3–5]. Secreted proteases have been found in abundance in O. viverrini secretions where they play key roles in food digestion and may be involved in bile duct inflammation. O. viverrini cathepsin F (Ov-CF-1) and cathepsin B (Ov-CB-1) were shown as the key enzymes in food catabolism [3,5]. In addition, the Ov-CB-1 is important in regulating the activity of Ov-CF-1 and that both enzymes work in concert to degrade host tissue macromolecules. Damage caused by the concerted action of these two cathepsins on the epithelium of the biliary tree may contribute the development of liver fluke associated CCA. Its role suggests it may be developed as an intervention target e.g. vaccine or drug target, in like fashion to cathepsin B of the human blood fluke Schistosoma mansoni [6]. In addition, there have major developments in transcriptomics of O. viverrini and Clonorchis sinensis [7,8] but there are no reports on the availability of gene manipulation approaches for O. viverrini and other related species.

Functional genomics have not been reported for O. viverrini or the related fish-borne fluke, C. sinensis. However, RNA interference and other methods for genetic manipulation will facilitate characterization of the role and importance of genes for these flukes [9,10]. Here we targeted cathepsin B of O. viverrini as a model gene for development of RNAi for O. viverrini and other fish-borne flukes. We show that cathepsin B is susceptible to RNAi knockdown, as evidenced by both reductions in transcript levels and indeed in enzyme activity ascribable to cathepsin B.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Adult of O. viverrini and cultivation

Metacercariae (MC) of O. viverrini were obtained from naturally infected cypriniid fish by pepsin digestion, as detailed [11]. Syrian golden hamsters, Mesocricetus auratus, were fed 50 MC by orogastric tube. Infected hamsters were euthanized six weeks after infection and adult O. viverrini flukes recovered from the gall bladder and bile ducts. Worms were washed five times with PBS supplemented with 2X antibiotics (streptomycin/penicillin, 200 μg/ml), and then cultured in RPMI medium supplemented with 1X antibiotics (streptomycin/penicillin, 100 μg/ml) at 37°C under 5% CO2 in air.

2.2 Synthesis of ds RNAs for O. viverrini cathepsin B1 and granulin

Double stranded-RNAs specific for the Ov-CB-1 gene (GenBank accession GQ303560) (residues 257–753 of the transcript, 497 bp) and the O. viverrini granulin (Ov-grn-1) (GenBank FJ436341) (residues 147–300 of the transcript, 154 bp) were synthesized. A TOPO plasmid clone containing the cDNA encoding Ov-CB-1[5] was used as DNA template for dsRNA of Ov-CB-1 using gene-target primers containing T7 promoter sequence (Fwd : 5′-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GGC ACG GGA ACA ATG GCC TCA CTG TC-3′; Rev : 5′-TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GGC GCT GCT TCG ACT GGT CCG TTG AT-3′). Freshly synthesized cDNA from adult O. viverrini [7] was employed as the template for dsRNA specific for the granulin (Ov-grn-1) gene [4] using gene-targeting primers containing T7 promoter sequences, 5′ TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GG TTACGGATGCTGTCCTATGG (Fwd) and TAA TAC GAC TCA CTA TAG GG CTTTCGAGCGTTGAGCATAA (Rev). The DNA containing the T7 RNA polymerase promoter sequence at each end (as indicated in italics) was used as templates for synthesized dsRNA. dsRNAs were synthesized and purified with the Megascript RNAi kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Concentration and purity of dsRNAs were determined with a ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA).

2.3 Electroporation of dsRNA and siRNA

Adult O. viverrini flukes were washed with four times with PBS containing penicillin and streptomycin (100 U, 100 μg/ml) and then incubated in RPMI containing antibiotics for 30 minutes at 37°C under 5% CO2 in air, prior to electroporation. Silencer® Cy™3 labeled siRNA (Ambion) (molecular mass, ~13.8 kDa) was used to investigate efficacy of square wave electroporation to deliver exogenous nucleic acid probes into the tissues and organs of O. viverrini. In brief, five μg of Silencer Cy3-labeled siRNA in 100 μl of RPMI supplemented with 1% glucose, 2 μM of E64 and streptomycin/penicillin (100 μg, 100 U/ml) was delivered to adult worms in 4 mm gap electroporation cuvettes (BTX, San Diego, CA, USA). Electroporation was performed at 125 volts with a single square wave pulse of 20 milliseconds duration (Electroporator Gene Pulser Xcell, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Pre-warmed culture medium was added after electroporation after which transformed flukes were cultivated at 37°C under 5% CO2 in air. Transformed flukes were examined 0, 24 and 48 hours later by bright field and fluorescence microscopy.

To deliver dsRNAs targeting cathepsin B1 or granulin by electroporation into adult O. viverrini, 30 flukes in 100 μl of RPMI 1640 medium with supplements (above) were dispensed into a 4 mm gap electroporation cuvette (BTX) along with 100 μg of the cognate dsRNA. After electroporation (as above), flukes were transferred into RPMI 1640 culture media at 37°C under 5% CO2 in air. Culture media were replaced at intervals of three days. Worms were harvested one, two or three days later for investigation of Ov-CB-1 , Ov-CB-2, Ov-grn-1 (granulin) and actin RNA expression or harvested at one, two, three, six or nine days later in order to examine cathepsin B protease activity.

2.4 Isolation of total RNAs and reverse-transcription PCR

Total RNA was isolated from adult O. viverrini flukes using Trizol® (Invitrogen. Total RNAs were treated with DNase I (Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania) to remove any contaminating DNA at 37 °C for 30 min and inactivated at 65°C for 10 min. RNA concentration was determined using a spectrophotometer (ND-1000, NanoDrop Technologies). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of DNase-treated RNA using the RevertAid™ First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit Fermentas. Expression of O. viverrini genes, Ov-CB-1, Ov-CB-2, granulin Ov-grn-1 and actin was investigated using both conventional RT-PCR and RT-quantitative PCR (-qPCR) using the following primers; for Ov-CB-1, Fwd, 5′-CAGCTGCGGGTGAAGTTACAGGAT and Rev, 5′-GGTCTTGGGTATGTTTTCATCGC, which span positions nt 38-249 of the Ov-CB-1 transcript (above). (These primers were designed to anneal outside of the target sequences of the dsRNA of Ov-CB-1 interference to avoid cross contamination). The specific primers for detecting Ov-CB-2 (GenBank GQ303559) transcripts, residues 51-264, 213 bp were CCAAGACGCCCAGTGTGGAGA (Fwd) and CTTTGGGAGACGCGTATCATC (Rev); and for Ov-grn-1, (residues 39-142; 104 bp) were TGCAACAACTTTCTCGATGG (Fwd) and GTAAGCCGCGACAACAAGTC (Rev). Amplifications were undertaken with Taq polymerase (Invitrogen) in 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 sec, annealing at 55°C for 30 sec and extension at 72°C for 1 min, following by a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis through ethidium-stained agarose (1%) gels. RT-qPCR was performed using the SYBR Green method and a Mx3005P Real-time-PCR System (Stratagene, Agilent Technologies Inc, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Real time reactions were carried out with 2XBrilliant SYBR® Green QPCR Master Mix (Stratagene) and, performed in triplicate, as follows: initial pre-heat cycle at 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, annealing at 55°C for 30 sec and extension at 72°C for 1 min. Expression levels of the Ov-CB-1 mRNA (and Ov-CB-2; and Ov-grn-1) and actin mRNA (OvAE1657, GenBank EL620339.1) [7], with actin included as an internal control, were determined. The mRNA level of Ov-CB-1 (or Ov-CB-2, or Ov-grn-1) was normalized with actin mRNA and presented as the unit value of 2−ΔΔCt where ΔΔCt = ΔCt (treated worms) − ΔCt (non-treated worms) [12].

2.5 Determination of cathepsin B activity

Soluble extracts of O. viverrini flukes, prepared as previously described [13,14] , were assayed for cathepsin B protease activity using a peptide substrate diagnostic for cathepsin B, Z-Arg-Arg- amino-methylcourmarin (AMC) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Release of AMC from hydrolyzed substrate was measured at 348 nm excitation and 440 nm emission at 37°C continuously for 300 min using a Spectra Max Gemini XPS fluorescence plate reader (Molecular Devices Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Optimal conditions for cleavage were determined by incubating 50 μg of the soluble fluke extracts or 5 μg of recombinant Ov-CB-1 enzyme, prepared as described [5], with substrate Z-Arg-Arg-AMC to a final concentration of 2 μM in 100 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.0), 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM EDTA (not shown). Because limited information was available on the specific activity of Ov-CB-1 in lysates of O. viverrini, the performance of the diagnostic substrate Z-Arg-Arg-AMC in monitoring this protease in lysates that would include other enzymes that might also cleave the substrate, and/or the performance of RNAi targeting Ov-CB-1, we monitored hydrolysis of Z-Arg-Arg-AMC over five hours, aiming to characterize potentially early and later proteolytic activity.

3. Results

3.1 Transduction of O. viverrini with siRNA by square wave electroporation

To investigate whether O. viverrini flukes might be amenable to genetic manipulation, adult parasites were subjected to square wave electroporation in the presence of labeled short interfering RNA. At 0 (Figures 1A and B), 24 (Figures 1C and D) and 48 (Figures 1E, F and G, H) hours after electroporation with Cy3-Silencer siRNA, the transduced flukes were examined by fluorescence microscopy. Cy3-siRNA fluorescence was evident at 24 hours (Figures 1C and D) and more intensely at 48 hours (Figures 1E, F and 1G, H). Cy3-fluorescence was evident throughout much of the body of the flukes, in particular in the vicinity of the oral sucker, ventral sucker, uterus and vitelline glands. (Bright field images are indeed included in the figure to provide anatomical context for the fluorescence localization signals.) The more intense signals at these sites may have resulted from entry of the probe into apertures on the body of the fluke including the mouth and genital pore. In addition, more generalized, weaker fluorescence was evident throughout the body of the flukes, perhaps reflecting entry of the probe through the tegument of the flukes at large. The results confirmed that utility of square wave electroporation to introduce exogenous nucleic acid probes into this liver fluke and the utility of Cy3-RNA to indicate location of the reporter siRNA in the transduced worms.

Figure 1. Opisthorchis viverrini flukes transduced by square wave electroporation with fluorescent, control Cy3-Silencer siRNA.

Adult O. viverrini transfected with Cy3-siRNA using square wave electroporation, employing a single pulse for 20 ms of 125 volts in the presence of 50 μg/ml of Cy3-siRNA. The worms were observed under bright field (panel A, C, E and G) and fluorescence (panel B, D, F and H) at 0, 24 and 48 hours after electroporation; 0 hours, A, B; 24 hours, C, D; 48 hours, E, F, G, H. Panels E and G present two different worms at 48 hours after electroporation; the two different panels are included to provide a more complete representation of the signals evident in the worms at this time point. (x4 magnification, Nikon Eclipse TS100 with Epi-Fluorescence Attachment (Mercury Lamp Illuminator model name, C-SHG) (Nikon Instruments Incorporation, Japan).

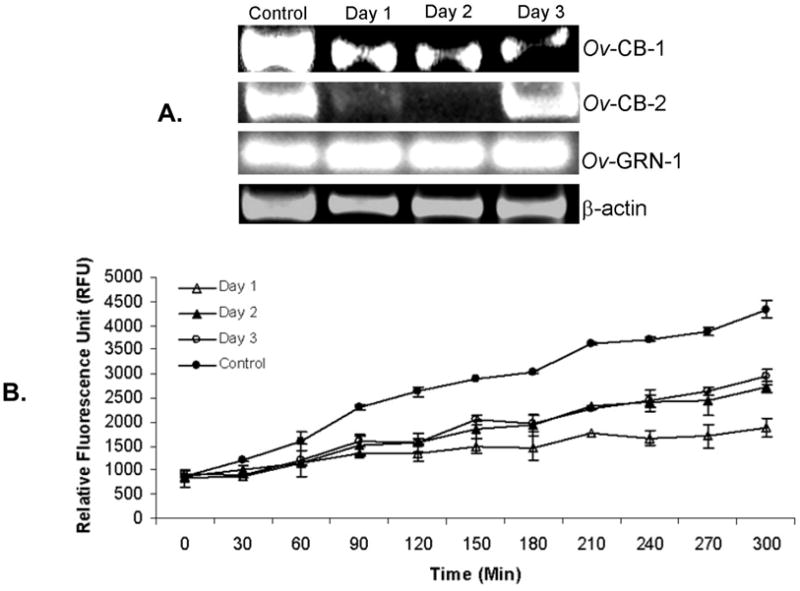

3.2 Double stranded RNA reduces O. viverrini cathepsin B transcript

Following the demonstration of introduction of Cy3-siRNA into adult flukes using the square wave electroporation protocols pioneered by Correnti and Pearce [15], we employed electroporation to transform adult O. viverrini parasites with dsRNAs specific for the gene encoding cathepsin B, Ov-CB-1 and, in a second group of worms, the gene encoding granulin, Ov-grn-1. Thereafter, in both groups, expression levels of Ov-CB-1, Ov-CB-2, Ov-grn-1 and actin were investigated by qRT-PCR of total RNAs collected at 1, 2 and 3 days after exposure by electroporation to the dsRNAs. Strong knockdown of Ov-CB-1 was seen, >90% at each of days 1, 2 after introduction of the dsRNA. We also saw strong knockdown of Ov-CB2 on days 1 and 2. By day 3, only ~50% knockdown of Ov-CB-2 was apparent. No silencing of granulin or actin was evident.

After treatment of the worms with dsRNA targeting Ov-CB-1, we monitored the levels of transcripts for Ov-CB-1 (the cognate gene target) and also three other genes, Ov-CB-2, actin and Ov-grn-1. We found significant silencing of Ov-CB-2 with dsRNA specific for Ov-CB-1, but no effect on two unrelated inducible genes, actin and granulin. There was a near total (>90%) reduction of Ov-CB-1 transcripts at one day after exposure to dsRNA. Likewise, near total knock-down in expression of Ov-CB-1 was maintained at two and three days after transduction (Figure 2). Also, we treated other worms with dsRNA targeting granulin, and then monitored expression levels of granulin (Ov-grn-1), cathepsin B1 (Ov-CB-1), cathepsin B2 (Ov-CB-2), and actin. When granulin was targeted, we saw a modest knockdown of granulin on day 1. However, by day 2, granulin expression levels had returned to levels before dsRNA treatment. By contrast, no effect was seen on Ov-CB-1, Ov-CB-2 or actin levels. The outcome of this control knockdown experiment suggested that off-target effects of RNAi may not be a widespread problem in functional genomics analysis in O. viverrini. Furthermore, we repeated the experiment, and cultured the worms for nine days after exposure to dsRNA. We observed that the near total silencing of Ov-CB-1 remained in place at nine days (data not shown).

Figure 2. Specific silencing of expression of the cathepsin B1 gene, Ov-CB-1 of Opisthorchis viverrini by dsRNA.

Panel A: Real-time RT-PCR targeting Ov-CB-1 cathepsin B revealed >90% knockdown in specific mRNA levels when monitored at one, two and three days after introduction of dsRNAs into cultured flukes. Knockdown of Ov-CB-2 was also seen at days one and two. By day three, only incomplete silencing of Ov-CB-2 remained apparent, in contrast to the >90% knockdown of Ov-CB-1, indicating the silencing of Ov-CB-2 had commenced to wane. Panel B: In like fashion, dsRNA induced silencing of the granulin gene, Ov-grn-1 was examined. This experiment was included here as a control to examine whether other genes in addition to Ov-CB-1 could be silenced. It also investigated whether silencing in O. viverrini was specific since the levels of Ov-CB-1 and Ov-CB-2 were examined here as well. These latter two genes appear unrelated in sequence and function of Ov-grn-1. For both panels A and B, relative mRNA expression levels of the Ov-CB-1, Ov-CB-2 and Ov-grn-1 mRNA were calculated by comparing the dsRNA treated group to the non-treated group. The mRNA levels were normalized by comparison to actin mRNA and presented as the unit value of 2-ΔΔCt where ΔΔCt = ΔCt (treated worms) − ΔCt (non-treated worms).

In addition to demonstrating specific knockdown of Ov-CB-1, these findings indicate, notably, the presence of active RNAi machinery in O. viverrini.

3.3 Robust knockdown of cathepsin B enzyme activity

Following qRT-PCR analysis that confirmed silencing of the Ov-CB-1 gene (above), other transformed flukes were assayed for cathepsin B protease activity at one, two and three days after treatment with dsRNA. In like fashion to the findings at 1, 2 and 3 days (Figure 2), ethidium bromide-stained gel analysis of RT-PCR products in control flukes and in flukes at one, two and three days after transfection revealed a steady decline of Ov-CB-1 transcripts following the electroporation of dsRNA specific for Ov-CB-1 (Figure 3, panel A). Hydrolysis of the cathepsin B diagnostic peptide Z-Arg-Arg-AMC was undertaken using extracts of the transformed flukes, collected at one, two and three days after exposure to the dsRNA. Liberation of AMC was monitored at five minute intervals for 300 min, which revealed significantly less cathepsin B activity in the transduced worms than in the control, electroporated flukes (Figure 3B). The difference between the control and dsRNA-treated flukes was evident in each of the three treatment groups, i.e. worms collected at one, two or three days after electroporation. More particularly, cathepsin B activity was substantially reduced by day one (60% reduction compared to control, non-dsRNA exposed flukes); at days two and three, cathepsin B activity was reduced by 45% and 40%, respectively, compared to controls (Figure 3). Recombinant Ov-CB-1 (5 μg) showed similar activity against Z-Arg-Arg-AMC to the soluble extract (5 μg) (not shown). The assay monitors hydrolysis of a fluorgenic, diagnostic peptide substrate. The differences in signals among the groups increased over time. We interpret this to reflect relatively long half-life of the cleaved products and accumulating amounts of the hydrolysis liberation products. The reduction of cathepsin B protease activity in the Ov-CB-1 knockdown worm group correlated with the reduction of cathepsin B mRNA levels shown by RT-PCR and RT-qPCR (Figures 2 and 3A).

Figure 3. Suppression of cathepsin B activity in Opisthorchis viverrini flukes by treatment with dsRNA specific for Ov-CB-1.

Reduction in expression of Ov-CB-1 in adult O. viverrini flukes transduced by square wave electroporation with 100 μg of dsRNA targeting the Ov-CB-1 gene at one, two and three days after treatment (panel A). Corresponding knockdown in cathepsin B protease activity observed at one, two and three days after exposure to dsRNA. Hydrolysis of Z-Arg-Arg-AMC was monitored continuously from 0 to 300 min after addition of soluble extracts of the flukes to the substrate (panel B).

4. Discussion

RNA interference (RNAi) is a key tool to investigate gene function and has been widely used in many eukaryotic pathogens including schistosomes [16,17]. The human liver fluke O. viverrini is endemic in Thailand, Laos and Cambodia where long standing infection is associated with cancer of the bile ducts, cholangiocarcinoma. Although O. viverrini infection remains a neglected tropical disease, recent advances on its transcriptome and proteome have provided an enormous new catalogue of sequences from which it will now be possible to develop new interventions [7,18,8]. However, functional genomics have not been reported for O. viverrini or the related C. sinensis. We now have described gene manipulation approaches for O. viverrini, including the deployment of square wave electroporation to introduce small RNAs into adult O. viverrini obtained from experimentally infected hamsters. More importantly, we have shown specific knockdown of transcripts encoding a cysteine protease, Ov-CB1 of O. viverrini. To our knowledge, this is not only the first description of genetic transformation of O. viverrini, but also the first report of successful RNAi in this parasite. It is relevant to note that key enzymes of the RNA interference machinery and pathways including dicer and drosha have been detected in recent transcriptomic analyses of O. viverrini [8].

RNAi targeting cathepsin B-like enzymes has been demonstrated in S. mansoni [19,20] and Fasciola hepatica [21]. Cathepsin B1 of O. viverrini is an essential enzyme for digestion of host hemoglobin, a primary food source for this parasite, and may also play a role in pathogenesis due to irritation of the bile duct. In O. viverrini, at least two forms of cathepsin B are expressed, including Ov-CB-1 and Ov-CB-2 [5]. Ov-CB-1 is also secreted as an active zymogen that is capable of trans-activating the related enzyme Ov-CF-1. We have previously predicted that Ov-CB-1 regulates Ov-CF-1 activity and that both enzymes participate to degrade host tissue contributing to the development of liver fluke-associated cholangiocarcinoma [5]. Accordingly, we plan to investigate the impact of RNAi targeting Ov-CB1 on the activity ascribable to Ov-CF-1. Peak suppression levels were seen at three days after exposure to the dsRNA, although strong suppression was still apparent at nine days after treatment. These results are redolent of those described with S. mansoni where the effect of knockdown of cathepsin B1 expression by RNAi remained evident for at least 30 days [19]. It will be of interest now to investigate RNAi targeting other genes of O. viverrini (and C. sinensis), including thioredoxin peroxidase, cathepsin F and other mediators that are predicted to play pivotal roles in molecular carcinogenesis [4,22,23]. Whereas RNAi is efficient in the two other flukes reported to date, schistosomes and Fasciola, it is thought that some genes are more responsive than other to this manipulation, perhaps influenced by the degree of difficulty in delivering the dsRNA or siRNA to target organs or tissues within the flukes [24].

In overview, we introduced genetic material by electroporation into O. viverrini, demonstrating the feasibility of this route of transformation of this neglected tropical pathogen. The findings with silencing of an endogenous gene, Ov-CB1, suggested the existence of a viable and functional RNAi pathway in this liver fluke. We consider that these results will not only facilitate further investigation of gene function in O. viverrini by RNAi approaches, including investigation of novel intervention targets, but they may likewise provide a path forward for genetic manipulation of other, even less-studied, food-borne trematodes [10,25].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Higher Education Research Promotion and National Research University Project of Thailand, Office of the Higher Education Commission, Grant under the program Strategic Scholarships for Frontier Research Network for the Ph.D. Program Thai Doctoral degree from the Office of the Higher Education Commission, Thailand and from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases award number UO1AI065871(the content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAID or the NIH).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sripa B, Kaewkes S, Sithithaworn P, Mairiang E, Laha T, Smout M, Pairojkul C, Bhudhisawasdi V, Tesana S, Thinkamrop B, Bethony JM, Loukas A, Brindley PJ. Liver fluke induces cholangiocarcinoma. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinlaor S, Hiraku Y, Ma N, Yongvanit P, Semba R, Oikawa S, Murata M, Sripa B, Sithithaworn P, Kawanishi S. Mechanism of NO-mediated oxidative and nitrative DNA damage in hamsters infected with Opisthorchis viverrini: a model of inflammation-mediated carcinogenesis. Nitric Oxide. 2004;11:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinlaor P, Kaewpitoon N, Laha T, Sripa B, Kaewkes S, Morales ME, Mann VH, Parriott SK, Suttiprapa S, Robinson MW, To J, Dalton JP, Loukas A, Brindley PJ. Cathepsin F cysteine protease of the human liver fluke, Opisthorchis viverrini. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smout MJ, Laha T, Mulvenna J, Sripa B, Suttiprapa S, Jones A, Brindley PJ, Loukas A. A granulin-like growth factor secreted by the carcinogenic liver fluke, Opisthorchis viverrini, promotes proliferation of host cells. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000611. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sripa J, Laha T, To J, Brindley PJ, Sripa B, Kaewkes S, Dalton JP, Robinson MW. Secreted cysteine proteases of the carcinogenic liver fluke, Opisthorchis viverrini: regulation of cathepsin F activation by autocatalysis and trans-processing by cathepsin B. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:781–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01433.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdulla MH, Lim KC, Sajid M, McKerrow JH, Caffrey CR. Schistosomiasis mansoni: novel chemotherapy using a cysteine protease inhibitor. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laha T, Pinlaor P, Mulvenna J, Sripa B, Sripa M, Smout MJ, Gasser RB, Brindley PJ, Loukas A. Gene discovery for the carcinogenic human liver fluke, Opisthorchis viverrini. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:189. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young ND, Campbell BE, Hall RS, Jex AR, Cantacessi C, Laha T, Sohn WM, Sripa B, Loukas A, Brindley PJ, Gasser RB. Unlocking the transcriptomes of two carcinogenic parasites, Clonorchis sinensis and Opisthorchis viverrini. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rinaldi G, Morales ME, Alrefaei YN, Cancela M, Castillo E, Dalton JP, Tort JF, Brindley PJ. RNA interference targeting leucine aminopeptidase blocks hatching of Schistosoma mansoni eggs. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2009;167:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rinaldi G, Morales ME, Cancela M, Castillo E, Brindley PJ, Tort JF. Development of functional genomic tools in trematodes: RNA interference and luciferase reporter gene activity in Fasciola hepatica. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tesana S, Kaewkes S, Srisawangwong T, Phinlaor S. The distribution and density of Opisthorchis viverrini metacercariae in cyprinoid fish in Khon Kaen Province. J Parasit Trop Med Ass Thai. 1985;8:36–39. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sripa B, Kaewkes S. Relationship between parasite-specific antibody responses and intensity of Opisthorchis viverrini infection in hamsters. Parasite Immunol. 2000;22:139–145. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2000.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wongratanacheewin S, Bunnag D, Vaeusorn N, Sirisinha S. Characterization of humoral immune response in the serum and bile of patients with opisthorchiasis and its application in immunodiagnosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1988;38:356–362. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1988.38.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Correnti JM, Pearce EJ. Transgene expression in Schistosoma mansoni: introduction of RNA into schistosomula by electroporation. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;137:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geldhof P, Visser A, Clark D, Saunders G, Britton C, Gilleard J, Berriman M, Knox D. RNA interference in parasitic helminths: current situation, potential pitfalls and future prospects. Parasitology. 2007;134:609–619. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006002071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stefanic S, Dvorak J, Horn M, Braschi S, Sojka D, Ruelas DS, Suzuki B, Lim KC, Hopkins SD, McKerrow JH, Caffrey CR. RNA interference in Schistosoma mansoni schistosomula: selectivity, sensitivity and operation for larger-scale screening. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mulvenna J, Sripa B, Brindley PJ, Gorman J, Jones MK, Colgrave ML, Jones A, Nawaratna S, Laha T, Suttiprapa S, Smout MJ, Loukas A. The secreted and surface proteomes of the adult stage of the carcinogenic human liver fluke Opisthorchis viverrini. Proteomics. 2010;10:1063–1078. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Correnti JM, Brindley PJ, Pearce EJ. Long-term suppression of cathepsin B levels by RNA interference retards schistosome growth. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2005;143:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skelly PJ, Da’dara A, Harn DA. Suppression of cathepsin B expression in Schistosoma mansoni by RNA interference. Int J Parasitol. 2003;33:363–369. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(03)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGonigle L, Mousley A, Marks NJ, Brennan GP, Dalton JP, Spithill TW, Day TA, Maule AG. The silencing of cysteine proteases in Fasciola hepatica newly excysted juveniles using RNA interference reduces gut penetration. Int J Parasitol. 2008;38:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suttiprapa S, Loukas A, Laha T, Wongkham S, Kaewkes S, Gaze S, Brindley PJ, Sripa B. Characterization of the antioxidant enzyme, thioredoxin peroxidase, from the carcinogenic human liver fluke, Opisthorchis viverrini. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008;160:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suttiprapa S, Mulvenna J, Huong NT, Pearson MS, Brindley PJ, Laha T, Wongkham S, Kaewkes S, Sripa B, Loukas A. Ov-APR-1, an aspartic protease from the carcinogenic liver fluke, Opisthorchis viverrini: functional expression, immunolocalization and subsite specificity. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1148–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krautz-Peterson G, Bhardwaj R, Faghiri Z, Tararam CA, Skelly PJ. RNA interference in schistosomes: machinery and methodology. Parasitology. 2010;137:485–495. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009991168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sripa B, Kaewkes S, Intapan PM, Maleewong W, Brindley PJ. Food-borne trematodiases in Southeast Asia epidemiology, pathology, clinical manifestation and control. Adv Parasitol. 2010;72:305–350. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(10)72011-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]