Abstract

Attitudes and beliefs about antiretroviral therapy (ART) may affect sexual risk behaviors among the general population in sub-Saharan Africa. We performed a cross-sectional population-based study in Kisumu, Kenya to test this hypothesis in October 2006. A total of 1655 participants were interviewed regarding attitudes and beliefs about ART and their sexual risk behaviors. The majority of participants, (71%) men and (70%) women, had heard of ART. Of these, 20% of men and 29% of women believed ART cures HIV. Among women, an attitude that “HIV is more controllable now that ART is available” was associated with sex with a non-spousal partner, increased lifetime number of sexual partners as well as a younger age at sexual debut. No significant associations with this factor were found among men. The belief that “ART cures HIV” was associated with younger age of sexual debut among women. The same belief was associated with an increased likelihood of exchanging sex for money/gifts and decreased likelihood of condom use at last sex among men. These findings were most significant for people aged 15–29 years. In high HIV seroprevalence populations with expanding access to ART, prevention programs must ensure their content counteracts misconceptions of ART in order to reduce high risk sexual behaviors, especially among youth.

Keywords: HIV-1, antiretroviral therapy, highly active, behavioral risk factor surveillance system, high risk sex, Africa, south of the Sahara, factor analysis, statistical

Introduction

In Kenya approximately 1.4 million people are infected with HIV (National AIDS and STI Control Programme, July 2008). Since 2001 access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in developing countries has moved to the forefront of the global health agenda. By the end of 2009 ART coverage in Kenya reached approximately 42–55% of people in need (Towards universal access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector, 2010). As ART availability continues to increase in sub-Saharan Africa, global health organizations have recognized the importance of maintaining the gains made through HIV prevention (Bringing HIV Prevention to Scale: an urgent global priority, 2007; HIV Prevention in the Era of Expanded Treatment Access, 2004). However, there is risk that an overemphasis on treatment programs will detract from prevention efforts and lead to reduced public concern about HIV and increased HIV risk behaviors (a phenomenon termed “risk compensation”).

Studies in the United States and Europe have characterized increases in risky sexual behavior since the introduction and scale up of ART (Gremy & Beltzer, 2004; Ostrow et al., 2002; van der Straten, Gomez, Saul, Quan, & Padian, 2000; Vanable, Ostrow, & McKirnan, 2003; Wilson & Minkoff, 2001). A meta-analysis of the association between ART use and various measures of sexual risk behaviors found that the prevalence of unprotected sex was elevated in persons who had reduced concerns about unsafe sex given the increased availability of ART (Crepaz, Hart, & Marks, 2004). Limited studies have evaluated the impact of attitudes and beliefs regarding ART on high risk sexual behavior in sub-Saharan Africa among patients enrolled in HIV care (Bateganya et al., 2005; Bunnell et al., 2006). To our knowledge, no study has examined the relationship between attitudes and beliefs regarding ART and risky sexual behavior among a general population in sub-Saharan Africa.

We conducted a population-based survey to determine if specific ART-related attitudes and beliefs were associated with sexual risk behavior after the roll out of ART and HIV care services in Kisumu, Kenya. Informed by the Health Belief Model (DiClemente & Peterson, 1994), we theorized that lower perceived severity of HIV and greater perceived benefit of ART would decrease the degree to which HIV is appraised as a threat. This would, in turn, promote engagement in risky sexual behaviors. We hypothesized that attitudes and beliefs reflecting decreased concern about HIV since ART is available would be associated with increased high risk sexual behavior. Where significant associations of attitudes and beliefs with indices of sexual risk behavior were observed, age was examined as an effect modifier. Finally, we validated the indices of high risk sexual behavior by examining their association with HIV and herpes simplex virus (HSV)-2 seroprevalence.

Methods

The complete study methodology is presented elsewhere (Cohen et al., 2009). In short, 40 clusters in Kisumu were selected and the number of households in these clusters was enumerated, with total number of households in our sampling frame determined by the target sample size. Households were selected by systematic random sampling and were visited three times if no resident was home before being replaced by another household. All persons 15–49 who slept in the house the prior night were eligible for participation. The final study protocol, consent, and questionnaire were approved by the ethical committee of the Kenya Medical Research Institute and the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco. Data collection took place from July to October 2006.

Survey measures

The data collection instrument, a questionnaire, was written in English and translated into Kiswahili and Dholuo. All materials for the study questionnaire were translated and back-translated to ensure accuracy. The back-translation was checked by a third person to detect any inconsistencies with amendments made to the translations as required before the instruments were finalized. Data were collected on demographic characteristics and participants responded to six items designed to quantify high risk sexual behaviors. These behaviors were operationally defined as behaviors shown in previous research to put individuals at risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV (Celentano et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2007; Cote et al., 2004; Lindley, Kerby, Nicholson, & Lu, 2007; Pettifor, van der Straten, Dunbar, Shiboski, & Padian, 2004; Zuma et al., 2005). Two items of sexual risk were continuous measures: lifetime number of sex partners and age at sexual debut. Four items were categorical (yes or no) measures: exchange of gifts or money for sex in the past 12 months, sex with a non-spouse in the past 12 months, any sex partner in the past 12 months, and condom use at last sex. ART-related attitudes and beliefs were adapted from prior studies and modified to fit the local context (Ostrow et al., 2002; van der Snoek et al., 2006; Vanable et al., 2003). For each item, participants selected one of three response options: agree, unsure, or disagree. In our previous work using both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (Cohen et al., 2009) we determined that these 13 variables could be summarized by two factors outlined in Table 1: a four-item factor measuring perceptions that HIV/AIDS is more controllable since the availability of ART and a seven-item factor that measures ART-related risk compensation. Although not summarized by either of the factors, we included the belief that “ART cures HIV/AIDS” as a single item predictor in subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Factors derived from ART-related attitudes and beliefs.a

| Factor 1: Belief that HIV is a more controllable disease due to ART availability (α=0.61)b | M (SD) |

| Now that ART is available, HIV is less serious than it used to be | 1.33 (0.93) |

| Now that ART is available, it is more important for people to know their HIV status | 1.77 (0.64) |

| Now that ART is available, HIV/AIDS is a controllable disease | 1.43 (0.88) |

| Now that ART is available, people are more willing to get tested for HIV | 0.80 (0.40) |

| Composite score | 5.32 (1.99) |

|

| |

| Factor 2: ART-related risk compensation (α=0.66)b | M (SD) |

|

| |

| Now that ART is available, people do not need to be as concerned about becoming HIV-positive | 0.34 (0.73) |

| Now that ART is available, condom use during sex is less necessary | 0.18 (0.54) |

| Now that ART is available, you are less worried about HIV infection | 0.18 (0.56) |

| Now that ART is available, you are more likely to have more than one sexual partner | 0.12 (0.46) |

| Now that ART is available, you are more willing to take a chance of getting infected or infecting someone else with HIV | 0.09 (0.40) |

| Now that ART is available, someone who is HIV-positive does not need to worry as much about condom use | 0.26 (0.66) |

| Now that ART is available, you are more likely to have sex without a condom | 0.04 (0.19) |

| Composite score | 1.20 (2.18) |

Factor analysis conducted on the 71% (n=1164) of the study participants that had heard of ART.

Participants rated responses to each item by selecting: disagree (0); unsure (1); or agree (2).

Data analysis

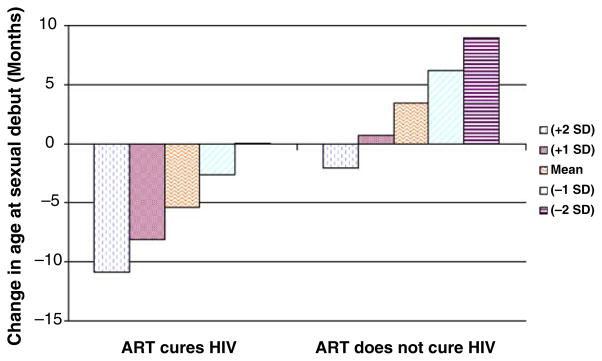

Data analysis was restricted to those participants who answered “Yes” to the survey question: “Have you heard about ART, the medicines for HIV?” Participants who marked “No” or “Not sure” were excluded. We theorized that the associations of ART-related attitudes and beliefs with sexual risk taking behavior may vary as a function of gender due to the distinct social norms governing expression sexual behaviors among men and women (Shisana & Davids, 2004). Consequently, separate logistic and linear regression analyses were conducted for men and women. First, we conducted logistic and linear regression analyses that were stratified by gender to examine whether ART-related attitudes and beliefs were associated with sexual risk taking. This model included all ART-related attitudes and beliefs(i.e., HIV is more controllable since ART, ART-related risk compensation, and ART cures HIV/AIDS) in the same regression block to examine the potentially independent effects of each. In order to facilitate the interpretation of the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) in logistic regression analyses, the composite scores for the two ART-related attitude and belief factors were transformed into z-scores (M=0, SD=±1). The results from the linear regression models were presented as β, the regression coefficient, and corresponding p-values to test for associations between continuous outcome and predictor variables. In order to provide an index of the magnitude of the association between ART-related attitudes and beliefs and continuous measures of sex risk, we utilized the non-standardized parameter estimates from the linear regression equation to calculate the predicted change in the age at sexual debut seen in Figure 1. Second, where significant associations between ART-related attitudes and beliefs and sexual risk taking behavior were observed within a given gender, we conducted follow-up analyses to examine whether this association varied by age category (i.e., 15–24, 25–29, 30–39 and 40–49 years). In follow-up analyses ART-related attitudes and beliefs were also entered simultaneously in the same regression block.

Figure 1.

Predicted change in age at sexual debut as a function of the perception that HIV is more controllable (now that ART is available) stratified by the belief that ART cures HIV among women who had heard of antiretroviral therapy in Kisumu, Kenya (n=555).

Results

Participant characteristics

Of the 1844 persons who were contacted regarding study participation, 1655 (90%) people enrolled in the study. Fifty-six percent of the 1655 participant were between the ages of 15 and 24 years. Most participants were Luo (77%) and Christian (95%). The majority (53%) had only a primary school education (Table 2). Twenty-five percent of women and 17% of men were HIV seropositive. Most participants (71%) had heard of ART, with no significant differences by gender (men: 71% vs. women: 70%, p=0.53). Of those who had heard of ART, 77% knew of a health facility where they could get ART. Nearly all (98%) agreed that ART prolongs life, but 23% answered “Yes” when asked if “HIV/AIDS can be cured with ART,” and 26% thought that ART had no side effects.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study population in Kisumu, Kenya.

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 749 (45) |

| Female | 906 (55) |

| Age category (years) | |

| 15–19 | 410 (25) |

| 20–24 | 504 (31) |

| 25–29 | 291 (17) |

| 30–39 | 297 (18) |

| 40–49 | 153 (9) |

| Education level | |

| No formal education | 25 (3) |

| Primary school only | 878 (53) |

| Secondary school | 600 (36) |

| Post-secondary education | 132 (8) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 694 (42) |

| Unemployed | 961 (58) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Luo | 1274 (77) |

| Luhya | 247 (15) |

| Other ethnicities | 134 (8) |

| Religion | |

| Catholic | 460 (28) |

| Protestant | 1110 (67) |

| Muslim | 63 (4) |

| Other | 10 (1) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 819 (50) |

| Single | 672 (40) |

| Separated/divorced | 96 (6) |

| Widowed | 68 (4) |

| Had heard of ART? | |

| Yes | 1164 (71) |

| No | 445 (27) |

| Not sure | 39 (2) |

ART-related attitudes and beliefs and sexual risk taking among women

Increased perceptions that HIV is more controllable since the availability of ART were associated with 42% higher odds of reporting sex with a non-spouse during the past 12 months among women. However, ART-related attitudes and beliefs were not significantly associated with exchanging gifts or money for sex during the past 12 months, any sexual partners in the past 12 months, or condom use at last sex. Increases in the perception that HIV is more controllable since the availability of ART were associated with a greater lifetime number of sexual partners and a younger age at sexual debut. A belief that ART cures HIV/AIDS was also associated with a younger age at sexual debut (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of attitudes and beliefs with risky sexual behavior among women and men who had heard of antiretroviral therapy in Kisumu, Kenya.

| Lifetime # sex partners (β) | Age at sexual debut (β) | Sex with a non-spouse in the last 12 months (AOR, 95% CI) | Condom use at last sex (AOR, 95% CI) | Gifts/money for sex in the last 12 months (AOR, 95% CI) | Sexual partner in last 12 months (AOR, 95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (n=635) | ||||||

| HIV is more controllable now that ART is available | 0.09 | −0.09 | 1.42 (1.09–1.86) | 1.08 (0.79–1.49) | 1.42 (0.93–2.15) | 1.41 (0.86–2.33) |

| ART related risk compensation | −0.08 | −0.06 | 0.98 (0.78–1.24) | 0.93 (0.62–1.39) | 0.95 (0.66–1.37) | 1.06 (0.72–1.56) |

| ART cures HIV | 0.03 | −0.14 | 1.00 (0.63–1.60) | 1.09 (0.56–2.14) | 0.95 (0.46–1.93) | 0.96 (0.42–2.17) |

| Men (n=529) | ||||||

| HIV is more controllable now that ART is available | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.18 (0.96–1.44) | 0.92 (0.67–1.27) | 0.98 (0.75–1.28) | 1.14 (0.87–1.50) |

| ART related risk compensation | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.95 (0.78–1.14) | 0.91 (0.64–1.29) | 1.19 (0.96–1.47) | 1.02 (0.81–1.29) |

| ART cures HIV | 0.05 | −0.07 | 0.94 (0.60–1.48) | 0.40 (0.21–0.75) | 1.86 (1.07–3.23) | 1.07 (0.60–1.91) |

Note: Bold values are significant at the p<0.05 level.

We examined the predicted change in age at sexual debut at varying magnitudes for perceptions that HIV is more controllable since ART (±2 SD) stratified by whether participants believed that ART cures HIV/AIDS. This provides an estimate of the additive effects of these ART-related attitudes and beliefs. For example, a belief that ART cures HIV/ AIDS and a score of two standard deviations above the mean on perceptions that HIV is more controllable since ART was associated with approximately a 10.9 month younger age at sexual debut. A belief that ART does not cure HIV/AIDS and a score of two standard deviations above the mean on perceptions that HIV is more controllable was independently associated with a 2.1 month younger age at sexual debut (Figure 1). The perception of increased risk compensation because ART is available was not significantly correlated with high risk sexual behavior in women.

The association between ART-related attitudes and beliefs and risky sexual behavior was examined within different age categories. Among women 25–29 years of age, those who believed that ART cures HIV/ AIDS had a significantly increased odds of reporting sex with a non-spouse during the past 12 months (AOR=3.66, p<0.05). Among women aged 15–24 years( β=0.17, p<0.05) and 30–39 years( β=0.19, p<0.05) a perception that HIV is more controllable since ART was associated with an increased lifetime number of sexual partners. A belief that ART cures HIV was associated with an earlier age at sexual debut for women ages 15–24 years( β= −0.14, p<0.05) and 30–39 years(β= −0.28, p<0.01). No statistically significant association between attitudes and beliefs about ART and risky sexual behavior were found for women in the 40–49 age group.

ART-related attitudes and beliefs and sexual risk taking among men

Men who believed that ART cures HIV/AIDS had an 86% higher odds of reporting exchange of gifts or money for sex in the past 12 months, and a 60% lower odds of reporting condom use at last sex. ART-related attitudes and beliefs were not significantly associated with sex with a non-spouse in the past 12 months or number of sexual partners in the last 12 months (Table 3).

Associations between ART-related attitudes and beliefs and exchange of gifts or money for sex during the past 12 months were examined within different age categories for men. A belief that ART cures HI V/AIDS was associated with an increased odds of exchanging gifts or money for sex among men 25–29 years of age (AOR=3.92, p<0.05). A belief that ART cures HIV / AIDS was associated with a decreased odds of reporting condom use at last sex among men 15–24 years of age (AOR=−0.30, p<0.05). No statistically significant association between attitudes and beliefs about ART and risky sexual behavior were found for men in the 30–39 or 40–49 age groups.

Biological outcome correlates

In order to establish the validity of our self-reported measures of risky sexual behaviors in the study population we examined correlations with biologic outcomes of interest, HIV and HSV-2 seroprevalence. Among women, increasing lifetime number of sex partners was associated with a greater likelihood of being HIV (OR=1.13, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.04–1.23, p<0.01) and HSV-2 (OR=1.16, 95% CI 1.09–1.22, p<0.001) seropositive. Younger age at sexual debut was associated with HIV-infection (OR=1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.05, p<0.01) but was not associated with increased HSV-2 seroprevalence (OR=1.01, 95% CI 0.99–1.04, p>0.20). Among men, only increasing lifetime number of sex partners was associated with an increased likelihood of being HIV (OR=1.20, 95% CI 1.07–1.34, p<0.01) and HSV-2 (OR=1.17, 95% CI 1.09–1.26, p<0.001) seropositive.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is one of the first population based studies to observe that ART related attitudes and beliefs are associated with sexual risk behavior in sub-Saharan Africa since the roll out of ART which started in 2003. Previous studies in this area were largely descriptive and assessed attitudes and beliefs about ART among HIV-positive persons and their partners or looked at sexual risk behavior as influenced by uptake of ART (Bateganya et al., 2005; Bunnell et al., 2006; Nachega et al., 2005). The results from this study highlight attitudes and beliefs about ART, prevalent in the general population of Kisumu, are associated with behaviors that potentially place individuals at risk for contracting HIV and other STIs.

In general, most participants were aware of ART and the majority had accurate information about the effectiveness of ART and how to access it. A sizeable minority had inaccurate expectations for ART. Prevention and education programs that target attitudes and beliefs about ART could address this potential driver of sexual risk taking. We also found that associations between various attitudes and beliefs about ART and the different high risk sexual behaviors varied as a function of gender. Among men, associations were present for transactional sex and lack of condom use. For women the associations were present for age at sexual debut, sex with a non-spouse in the last 12 months and lifetime number of sex partners. In Kenya, as in many cultures, it is more socially acceptable for men to have more sexual partners overall and more partners outside of marriage, while women are expected to be monogamous and married at an early age (Shisana & Davids, 2004). Our differential findings regarding the role of ART-related attitudes and beliefs reflect these gender-based cultural norms which limit the extent to which women can control many aspects of their sexual behavior. In Kenya, women may have more control over their sexual behavior prior to marriage, and individual-level factors such as ART-related attitudes and beliefs can exert an influence (i.e., age at sexual debut). However, women may have less control over their sexual behavior after marriage (e.g., condom negotiation with their primary partner), and individual-level factors such as ART-related attitudes and beliefs cannot meaningfully influence risk behavior. On the contrary, it may also be that women are less likely to disclose socially unacceptable sexual behaviors, and this could explain our differential findings as a function of gender.

Young people are a group at high risk for HIV acquisition and transmission and are more likely to have become sexually active during the period in which ART became available in Kisumu. They are also more likely to have had their first sexual experiences influenced by their perception of ART, though certainly not all had their sexual debut post-ART roll out. We found that the associations between ART-related attitudes and beliefs and high risk sexual behavior we saw in the general study population were strongest among the youngest participants when we stratified the data by age. For young women having an earlier age of sexual debut and increased life-time number of sexual partners has been shown to be strongly associated with increased HIV risk (Chen et al., 2007; Gregson et al., 2006; Pettifor et al., 2004) possibly due in part to biological factors (Moscicki, Ma, Holland, & Vermund, 2001; Moss et al., 1991).

The most consistent correlates of high risk sexual behavior were a greater perception that HIV is more controllable now that ART is available and a belief that ART cures HIV/AIDS. While HIV may indeed be more controllable when ART is widely available, given the reality of ART access, distribution and cost in sub-Saharan Africa, this statement is an overly optimistic expectation for ART at this place and time. An expectation that ART cures HIV is a serious misconception that has the potential to derail HIV control efforts. Prevention agendas should include educational programs with an aim to reduce the spread of this misinformation and overly optimistic perceptions about ART, especially among young sexually active adults.

This study utilized a probability-based sampling methodology to evaluate the association between ART related attitudes and beliefs and high risk sexual behavior among the general population in Kisumu. This is a strength compared with other studies in the developed world which only targeted high risk groups or those receiving ART through convenience sampling methods. Limitations of our study include potential confounding from other determinants of risk. Because this is a cross-sectional study, it is also plausible that persons who engage in risky sexual behavior experience cognitive dissonance such that they are psychologically motivated to reduce their perceptions of the severity of HIV in the era of ART. It is also plausible that many of the participants had their sexual debut and/or majority of their sexual partners prior to the roll out of ART in Kisumu, confounding our study results for those metrics. However, by focusing on associations seen between perceptions of ART and high risk sexual behaviors among the youngest participants( < 25 years of age) we have tried to minimize this confounding. It is also noteworthy that the measure of ART-related attitudes and beliefs in this study utilized three response options to reduce participant burden. Despite the fact that this limited the precision of our measure of ART-related attitudes and beliefs, it was significantly associated with multiple indices of sexual risk taking. Although we did observe an association between one of the ART-related attitudes and beliefs with lifetime number of sexual partners, findings were not consistent when we examined the number of sexual partners in the last 12 months. Some of these lifetime sexual partnerships may have preceded the roll out of ART, especially in older participants. However, ART-related attitudes and beliefs were associated with a greater number of lifetime sexual partners among young women (15–24 years), who were more likely to have had their sexual debut during the roll out of ART. Although this study does not provide definitive evidence that these attitudes and beliefs about ART promote risky sexual behavior, findings support the need for further longitudinal research, with improved measures, in the future.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Operations Research on AIDS Care and Treatment in Africa (ORACTA) grant. RMS was supported by the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Dean’s Research Fund and the UCSF Social and Behavioral Science Area of Concentration Scholarship Fund.

Our success in completing this study was due to the tireless efforts of the research team in the field especially field team leaders(Solace Awuor Amboga, Vitalis Akora, John Marie Mbeche, and Juma G. Juma), the lab (Hannah Kimenyu and Albert Okumu), the data (Edmund Njeru Njagi and Hesbon Ooko), and administrative (Jacob Magige, Michael Mureithi, and Barrack Onyango) offices, as well as strong collaboration and support from the community leaders and residents of Kisumu. The authors also thank the following for their generous support: The Director KEMRI, the Director Centre for Microbiology Research; and the UNIM Project for their hospitality. This work is published with the permission of the Director KEMRI.

References

- Bateganya M, Colfax G, Shafer LA, Kityo C, Mugyenyi P, Serwadda D, Bangsberg D. Antiretroviral therapy and sexual behavior: A comparative study between antiretroviral-naive and - experienced patients at an urban HIV/AIDS care and research center in Kampala, Uganda. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005;19(11):760–768. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringing HIV Prevention to Scale: An urgent global priority. Global Health HIV Prevention Working Group; 2007. Document Number. [Google Scholar]

- Bunnell R, Ekwaru JP, Solberg P, Wamai N, Bikaako-Kajura W, Were W, Mermin J. Changes in sexual behavior and risk of HIV transmission after antiretroviral therapy and prevention interventions in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2006;20(1):85–92. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196566.40702.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celentano DD, Sirirojn B, Sutcliffe CG, Quan VM, Thomson N, Keawvichit R, Aramrattana A. Sexually transmitted infections and sexual and substance use correlates among young adults in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2008;35(4):400–405. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815fd412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Jha P, Stirling B, Sgaier SK, Daid T, Kaul R for the International Studies of HIV/ AIDS (ISHA) investigators. Sexual risk factors for HIV infection in early and advanced HIV epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic overview of 68 epidemiological studies. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(10):e1001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CR, Montandon M, Carrico AW, Shiboski S, Bostrom A, Obure A, Bukusi EA. Association of attitudes and beliefs towards antiretroviral therapy with HIV-seroprevalence in the general population of Kisumu, Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(3):e4573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote AM, Sobela F, Dzokoto A, Nzambi K, Asamoah-Adu C, Labbe AC, Pepin J. Transactional sex is the driving force in the dynamics of HIV in Accra, Ghana. AIDS. 2004;18(6):917–925. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200404090-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Hart TA, Marks G. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and sexual risk behavior: A meta-analytic review. JAMA. 2004;292(2):224–236. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente R, Peterson JL, editors. Preventing AIDS: Theories and methods of behavioral interventions. New York City: Plenum Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Garnett GP, Nyamukapa CA, Hallett TB, Lewis JJ, Mason PR, Anderson RM. HIV decline associated with behavior change in eastern Zimbabwe. Science. 2006;311(5761):664–666. doi: 10.1126/science.1121054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gremy I, Beltzer N. HIV risk and condom use in the adult heterosexual population in France between 1992 and 2001: Return to the starting point? AIDS. 2004;18(5):805–809. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200403260-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIV Prevention in the Era of Expanded Treatment Access. Global HIV Prevention Working Group; 2004. Retrieved from http://www.globalhivprevention.org/pdfs/Prevention%20in%20Era%20of%20Treatment.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Lindley LL, Kerby MB, Nicholson TJ, Lu N. Sexual behaviors and sexually transmitted infections among self-identified lesbian and bisexual college women. Journal of LGBT Health Research. 2007;3(3):41–54. doi: 10.1080/15574090802093323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscicki AB, Ma Y, Holland C, Vermund SH. Cervical ectopy in adolescent girls with and without human immunodeficiency virus infection. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2001;183(6):865–870. doi: 10.1086/319261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss GB, Clemetson D, D’Costa L, Plummer FA, Ndinya-Achola JO, Reilly M, Kreiss JK. Association of cervical ectopy with heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus: Results of a study of couples in Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1991;164(3):588–591. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.3.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachega JB, Lehman DA, Hlatshwayo D, Mothopeng R, Chaisson RE, Karstaedt AS. HIV/AIDS and antiretroviral treatment knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and practices in HIV-infected adults in Soweto, South Africa. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;38(2):196–201. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200502010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS and STI Control Programme, M. o. H., Kenya. Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey 2007: Preliminary Report. Nairobi, Kenya: Jul, 2008. Document Number. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrow DE, Fox KJ, Chmiel JS, Silvestre A, Visscher BR, Vanable PA, Strathdee SA. Attitudes towards highly active antiretroviral therapy are associated with sexual risk taking among HIV-infected and uninfected homosexual men. AIDS. 2002;16(5):775–780. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203290-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor AE, van der Straten A, Dunbar MS, Shiboski SC, Padian NS. Early age of first sex: A risk factor for HIV infection among women in Zimbabwe. AIDS. 2004;18(10):1435–1442. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131338.61042.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shisana O, Davids A. Correcting gender inequalities is central to controlling HIV/AIDS. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004;82(11):812. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towards universal access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Document Number. [Google Scholar]

- van der Snoek EM, de Wit JB, Gotz HM, Mulder PG, Neumann MH, van der Meijden WI. Incidence of sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infection in men who have sex with men related to knowledge, perceived susceptibility, and perceived severity of sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infection: Dutch MSM-Cohort Study. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;33(3):193–198. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000194593.58251.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Straten A, Gomez CA, Saul J, Quan J, Padian N. Sexual risk behaviors among heterosexual HIV serodiscordant couples in the era of post-exposure prevention and viral suppressive therapy. AIDS. 2000;14(4):F47–F54. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003100-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanable PA, Ostrow DG, McKirnan DJ. Viral load and HIV treatment attitudes as correlates of sexual risk behavior among HIV-positive gay men. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2003;54(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00483-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TE, Minkoff H. Brief report: Condom use consistency associated with beliefs regarding HIV disease transmission among women receiving HIV antiretroviral therapy. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2001;27(3):289–291. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200107010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuma K, Lurie MN, Williams BG, Mkaya-Mwamburi D, Garnett GP, Sturm AW. Risk factors of sexually transmitted infections among migrant and non-migrant sexual partnerships from rural South Africa. Epidemiology and Infection. 2005;133(3):421–428. doi: 10.1017/s0950268804003607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]