Abstract

We have shown that the cellular process of macroautophagy plays a protective role in HL-1 cardiomyocytes subjected to simulated ischemia/reperfusion (sI/R) (Hamacher-Brady et al. in J Biol Chem 281(40):29776–29787). Since the nucleoside adenosine has been shown to mimic both early and late phase ischemic preconditioning, a potent cardioprotective phenomenon, the purpose of this study was to determine the effect of adenosine on autophagosome formation. Autophagy is a highly regulated intracellular degradation process by which cells remove cytosolic long-lived proteins and damaged organelles, and can be monitored by imaging the incorporation of microtubule-associated light chain 3 (LC3) fused to a fluorescent protein (GFP or mCherry) into nascent autophagosomes. We investigated the effect of adenosine receptor agonists on autophagy and cell survival following sI/R in GFP-LC3 infected HL-1 cells and neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. The A1 adenosine receptor agonist 2-chloro-N(6)-cyclopentyl-adenosine (CCPA) (100 nM) caused an increase in the number of autophagosomes within 10 min of treatment; the effect persisted for at least 300 min. A significant inhibition of autophagy and loss of protection against sI/R measured by release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), was demonstrated in CCPA-pretreated cells treated with an A1 receptor antagonist, a phospholipase C inhibitor, or an intracellular Ca(+2) chelator. To determine whether autophagy was required for the protective effect of CCPA, autophagy was blocked with a dominant negative inhibitor (Atg5K130R) delivered by transient transfection (in HL-1 cells) or protein transduction (in adult rat cardiomyocytes). CCPA attenuated LDH release after sI/R, but protection was lost when autophagy was blocked. To assess autophagy in vivo, transgenic mice expressing the red fluorescent autophagy marker mCherry-LC3 under the control of the alpha myosin heavy chain promoter were treated with CCPA 1 mg/kg i.p. Fluorescence microscopy of cryosections taken from the left ventricle 30 min after CCPA injection revealed a large increase in the number of mCherry-LC3-labeled structures, indicating the induction of autophagy by CCPA in vivo. Taken together, these results indicate that autophagy plays an important role in mediating the cardioprotective effects conferred by adenosine pretreatment.

Keywords: Preconditioning, Ischemia/reperfusion, Autophagy, Cardiomyocytes, Adenosine, Cardioprotection

Introduction

The induction of ischemic tolerance in the heart to prevent and treat myocardial infarction in the setting of ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury continues to be an area of intense investigation. Many of these efforts have centered around the elucidation of the mechanisms underlying the phenomenon of ischemic preconditioning with the intent to develop new therapies based on the identification of endogenous triggers and putative mediators. One agent that has been shown to mimic both acute (early) and delayed (late phase) preconditioning is the nucleoside adenosine [2, 3]. Purportedly, the cardioprotective effects of the agent are mediated via activation of various adenosine receptor subtypes, the primary one being the A1 receptor [3]. Ligation of the adenosine A1 receptor is followed by activation of phospholipase C (PLC) and protein kinase C (PKC) [2]. These, in turn, have been reported to confer protection by activation of an ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channel within mitochondria (mKATP) prior to the onset of prolonged ischemia [4, 5]. Although it has been suggested that the mKATP channel is the end effector of ischemic preconditioning, just how activation of the mKATP channel results in cardioprotection is unknown, although our understanding continues to grow [6]. A number of other potential effectors have been studied including anion channels, the cytoskeleton, and the closure of gap junctions [3, 7]. Our previous work in HL-1 cells indicated that suppressing autophagy in the context of simulated I/R (sI/R) increased cell death, suggesting the possibility that autophagy was part of a cellular protective response [1]. For that reason we hypothesized that autophagy might be involved in ischemic or pharmacologic preconditioning. Pharmacologic inhibitors of autophagy have off-target side effects that may confound interpretation of the results [8, 9]. For that reason we used a point mutation of the essential autophagy gene Atg5. Mutation of lysine 130 on Atg5 prevents conjugation of ubiquitin-like Atg12 onto the acceptor lysine by Atg7 [10]. We and others have shown that Atg5K130R functions as a potent dominant negative, inhibiting autophagy at the earliest stage [1, 11, 12]. Atg5 is not known to participate in other pathways besides autophagy, and therefore Atg5K130R is the most specific inhibitor available.

Macroautophagy (referred to hereafter as autophagy) is the only means to remove dysfunctional organelles such as mitochondria and insoluble protein aggregates [13]. The process is initiated by a number of stressors including starvation, oxidative stress, lipopolysaccharide exposure, and sI/R injury. Many studies of autophagy now rely on scoring the number of autophagosomes, which can be detected in transfected cells or transgenic animals expressing GFP (or the red fluorescent protein mCherry) fused to the protein LC3, which is incorporated into nascent autophagosomes [14]. In the setting of myocardial sI/R injury, an increased prevalence of autophagosomes has been documented [1]. In an in vivo model of myocardial ischemia, a reduction in stunning correlated with increased expression of Beclin1 (an autophagy gene) [15]. Moreover, this group observed that within the tissue, cells with numerous autophagosomes were not TUNEL positive, suggesting that upregulating autophagy might prevent apoptosis. Since the end-effector(s) of adenosine-mediated protection is unknown, the purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that adenosine-mediated cardioprotection requires activation of autophagy, and that autophagy is necessary and sufficient for achieving cardioprotection. To test these hypotheses, we subjected the HL-1 myocyte cell line to simulated I/R and treated mCherry-LC3 transgenic mice with 2-chloro-N(6)-cyclopentyladenosine (CCPA), a selective adenosine A1 receptor agonist.

Experimental procedures

Reagents

BAPTA-AM and Bafilomycin A1 (Baf) were purchased from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA, USA); CCPA, DPCPX and thapsigargin (TG) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Cell culture

Cells of the murine atrial-derived cardiac cell line HL-116 were plated in gelatin/fibronectin-coated culture vessels and maintained in Claycomb medium [16] (JRH Biosciences, Lenexa, KS) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 0.1 mm norepinephrine, 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 U/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 µg/mL amphotericin B.

Freshly isolated adult rat cardiomyocytes were prepared from 200 to 250 g male Sprague Dawley rats, following standard methods. The animals were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital, and all animal procedures were in accordance with institutional guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. After an injection of heparin (100 U/kg) into the hepatic vein, the heart was excised and the aorta was cannulated. The heart was perfused retrogradely with a Ca2+-free buffer followed by perfusion with 0.6 mg/mL collagenase (CLS 2, Worthington Biochemical Corporation, USA) and 8.3 µM CaCl2 in perfusion buffer. After perfusion with collagenase solution for 15 min, the heart was minced in the same collagenase solution and the myocytes were filtered through a fine gauze. A stopping buffer containing 5% bovine calf serum and 12.5 µM CaCl2 was added to the cells, followed by calcium stepwise reintroduction up to a concentration of 1 mM. The cells were centrifuged at 100×g for 1 min, and the pellet was washed in M199 medium (Invitrogen), containing 10 mM HEPES, 5 mM taurine, 5 mM creatine, 2 mM carnitine, 0.5% free fatty acid BSA and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin. Cardiomyocytes were plated with laminin (Roche) (20 µg/mL laminin for glass, or 10 µg/mL for plastic dishes) at 5 × 104 cells per dish. The cells were incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 2 h, then the medium was replaced with the same fresh medium, and the experiments were performed 24 h later. Cell viability based on rod-shaped morphology at the outset of the experiment was routinely >90%.

Transfections, infections, and protein transduction

HL-1 cells were transfected with the indicated vectors using the transfection reagent Effectene (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, achieving at least 40% transfection efficiency. For experiments aimed at determining autophagic flux, HL-1 cells were transfected with GFP–LC3 and the indicated vector at a ratio of 1:3 µg DNA. For infections, HL-1 cells or adult rat cardiomyocytes were infected with GFP-LC3 adenovirus for 2 h, washed in PBS and re-fed with the Claycomb medium or M199 medium, respectively. All the experiments were performed 20 h after infection. The dominant negative pmCherryAtg5K130R was previously described [1] and has been deposited with Addgene. For adult cardiomyocytes, GFP-LC3 infected cells were incubated with recombinant Tat-Atg5K130R for 30 min before adding CCPA. Tat-Atg5K130R was prepared by cloning Atg5K130R into the pHA-TAT construct previously described [17]. Recombinant protein was purified as previously described [11, 17, 18].

High- and low-nutrient conditions

Cells were plated in 14-mm-diameter glass bottom micro-well dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA, USA). For high-nutrient conditions, experiments were performed in fully supplemented Claycomb medium. For low-nutrient conditions, experiments were performed in modified Krebs-Henseleit buffer (MKH) (in mM: 110 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.25 MgSO4, 1.2 CaCl2, 25 NaHCO3, 15 glucose, 20 HEPES, pH 7.4) and incubation at 95% room air and 5% CO2.

Simulated ischemia/reperfusion (sI/R)

Cells were plated in 14-mm diameter glass bottom microwell dishes (MatTek), and ischemia was introduced by a buffer exchange to ischemia-mimetic solution (in mM: 20 deoxy-glucose, 125 NaCl, 8 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.25 MgSO4, 1.2 CaCl2, 6.25 NaHCO3, 5 sodium lactate, 20 HEPES, pH 6.6) and placing the dishes in hypoxic pouches (GasPak™ EZ, BD Biosciences) equilibrated with 95% N2, 5% CO2. After 2 h of simulated ischemia, reperfusion was initiated by a buffer exchange to normoxic MKH buffer and incubation at 95% room air, 5% CO2. Controls incubated in normoxic MKH buffer were run in parallel for each condition for periods of time that corresponded with those of the experimental groups.

Wide-field fluorescence microscopy

Cells were observed through a Nikon TE300 fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA) equipped with a ×10 lens (0.3 NA, Nikon), a ×40 Plan Fluor and a ×60 Plan Apo objective (1.4 and 1.3 NA oil immersion lenses; Nikon), a Z-motor (ProScanII, Prior Scientific, Rockland, MA, USA), a cooled CCD camera (Orca-ER, Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ, USA) and automated excitation and emission filter wheels controlled by a LAMBDA 10-2 (Sutter Instrument, Novato, CA, USA) operated by MetaMorph 6.2r4 (Molecular Devices Co., Downington, PA, USA). Fluorescence was excited through an excitation filter for fluorescein isothiocyanate (HQ480/×40), and an emission filter (HQ535/50 m).

Determination of autophagic content and flux

To analyze autophagic flux, GFP–LC3-expressing cells were subjected to the indicated experimental conditions with and without a cell-permeable lysosomal inhibitor Bafilomycin A1 (50 nm, vacuolar H+-ATPase inhibitor) to inhibit autophagosome–lysosome fusion [19], for an interval of 3 h. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 15 min.

To analyze the number of GFP–LC3 puncta in population, cells were inspected at 60× magnification and classified as: (a) cells with predominantly diffuse GFP–LC3 fluorescence; or as (b) cells with numerous GFP–LC3 puncta (>30 dots/cell), representing autophagosomes. At least 200 cells were scored for each condition in three or more independent experiments.

Experiments with preconditioning agents

2-Chloro-N(6)-cyclopentyladenosine (CCPA) at concentrations of 0.001–0.1 nM was applied to the cell cultures for 15 min following a 15 min preincubation with various inhibitors (Sigma): 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dimethylxanthine (DPCPX, 1 µM), BAPTA-AM (25 µM), U73122 (2 µM) or thapsigargin (TG, 1 µM). The cell cultures were washed with PBS prior to the experimental treatment.

Release of LDH

Protein content and LDH activity were determined according to El-Ani et al. [20]. Briefly, 25 µL supernatants from 35 mm dishes were transferred into wells of a 96-well plate, and the LDH activities were determined with an LDH-L kit (Sigma), according to the manufacturer. The product of the enzyme was measured spectrophotometrically at 30°C at a wavelength of 340 nm as described previously [21]. The results were expressed relative to the control (X-fold) in the same experiment. Each experiment was done in triplicate and was repeated at least three times.

Nuclear staining

Cells were stained immediately after sI/R with propidium iodide (5 µg/mL), which stains nuclei of cells whose plasma membranes have become permeable because of cell damage. The assay was performed according to Nieminen et al. [22]. For counterstaining we used Hoechst 33342 (10 µM), which stains the nuclei of all cells.

Transgenic mCherry-LC3 mice-Cardiac-specific expressing mCherry-LC3 transgenic mice were created in the FVB/N strain by pronuclear injection of murine alpha myosin heavy chain promoter driven mCherry-LC3 transgene in front of the human growth hormone poly adenylation signal [23]. Mice were injected with saline or CCPA (1 mg/kg, i.p.), and 30 min later they were euthanized with pentobarbital and the hearts excised and embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature medium for cryosectioning and fluorescence microscopy. All animal procedures were carried out in accordance with institutional guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Statistics

The probability of statistically significant differences between two experimental groups was determined by Student’s t-test. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments unless stated otherwise.

Results

Adenosine receptor-selective effects on autophagy

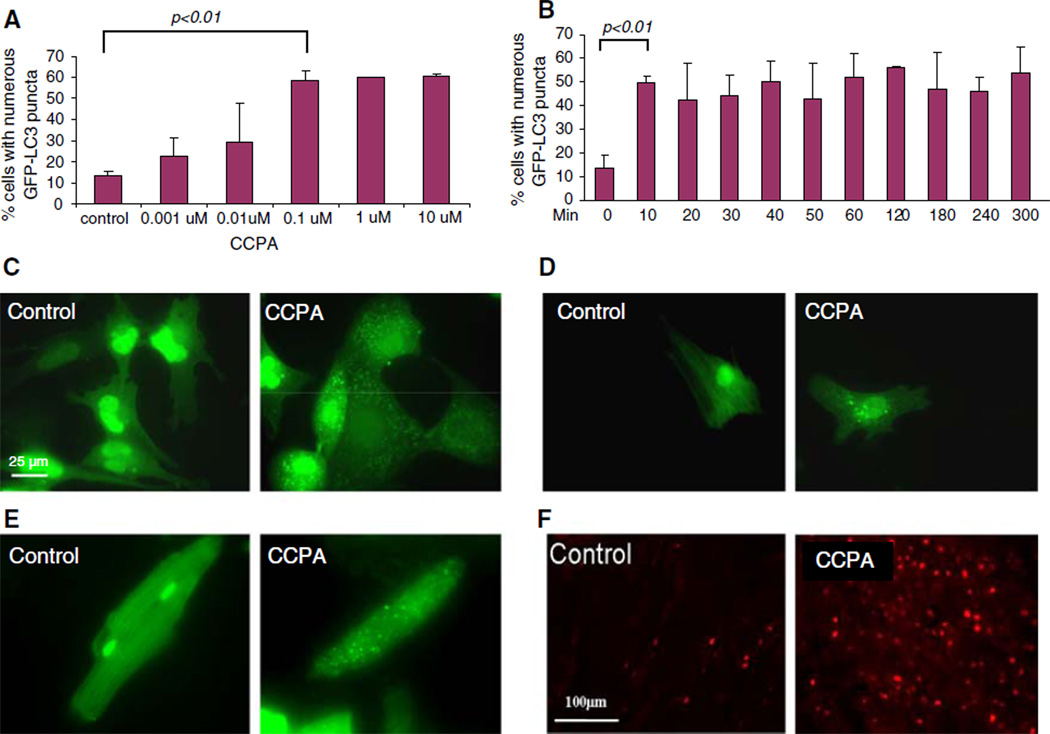

We assessed the role of the adenosine A1 receptor using the selective agonist CCPA. As shown in Fig. 1, CCPA induced autophagy in a dose-dependent fashion. Autophagy was upregulated within 10 min after the addition of CCPA, and was sustained for several hours, consistent with the kinetics of the preconditioned state. We observed an increase in the number of autophagosomes in response to CCPA in HL-1 cells (1C), neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (1D), adult cardiomyocytes (1E), and in vivo in the hearts of mCherry-LC3 transgenic mice (1F).

Fig. 1.

Adenosine receptor-selective effects on autophagy. a GFP–LC3 transfected HL-1 cells were treated for 120 min in full medium (FM) with various concentrations (0.001–10 µM) of CCPA. b GFP-LC3-transfected HL-1 cells were treated with 100 nM CCPA for the indicated time, then fixed with paraformaldehyde and scored by fluorescence microscopy. c Representative images of HL-1 cells expressing GFP-LC3, which is diffuse in quiescent cells and punctate in CCPA-treated cells (PC). d Representative images of neonatal cardiomyocytes under control conditions or 10 min after administration of 100 nM CCPA. e Representative images of adult cardiomyocytes under control conditions or 10 min after administration of 100 nM CCPA. f Transgenic mice expressing mCherry-LC3 under the αMHC promoter received an i.p. injection of saline or 1 mg/kg CCPA, then were sacrificed 30 min later and heart tissue was processed for fluorescence microscopy. The increase in fluorescent red puncta reflects upregulation of autophagy

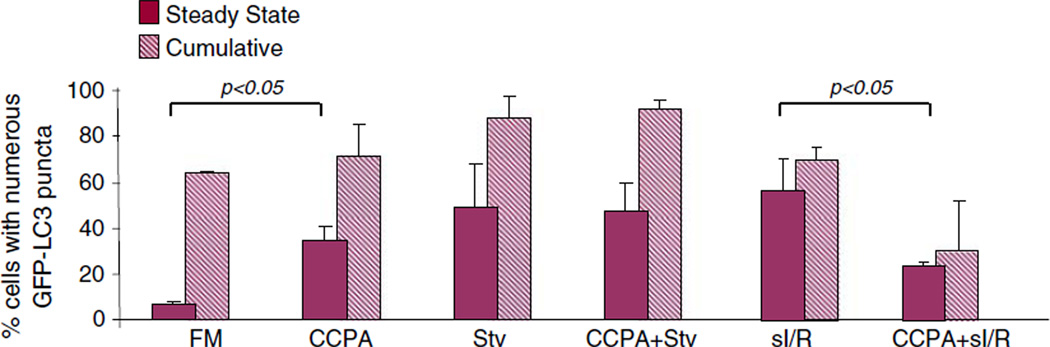

Effect of CCPA on autophagic flux under conditions of starvation or sI/R

An increase in the number of autophagosomes can be due to increased formation of autophagosomes or a decrease in their clearance through lysosomal degradation. To measure flux, we inhibited autophagosomal degradation with Bafilomycin A1: an increase in the abundance of autophagosomes compared with steady state conditions (no Bafilomycin) reflects increased production. As shown in Fig. 2, CCPA increased the percentage of cells with numerous autophagosomes under both steady-state and cumulative conditions, indicating that CCPA increases autophagy rather than interfering with degradation. CCPA has no effect on the extent of autophagy induced by starvation. Simulated ischemia and reperfusion (sI/R) results in an increase in the percentage of cells with numerous autophagosomes seen under steady state conditions, but this is due to impaired clearance rather than increased formation, as there is no significant increase in the number in the presence of Bafilomycin. Fewer autophagosomes were observed after sI/R in CCPA-treated cells. Since CCPA did not reduce autophagic flux induced by starvation, it likely does not interfere with formation of autophagosomes in response to sI/R. If autophagy is upregulated during sI/Rin an attempt to respond to the stress of nutrient deprivation and oxidants, then the diminished autophagy seen in CCPA-treated cells after sI/R may indicate that the cells experienced less stress, and therefore less autophagy is required during reperfusion (reparative autophagy).

Fig. 2.

Effect of CCPA on autophagic flux under conditions of starvation or sI/R. HL-1 cells were infected with adv-GFP-LC3, treated with or without 100 nM CCPA in full medium (FM) for 10 min, then subjected either to starvation (amino acid deprivation in MKH) (Stv) for 3 h, or simulated I/R (2 h sI, 3 h R). Steady-state and cumulative conditions were assessed by incubating cells with or without the lysosomal inhibitor Bafilomycin during the starvation or reperfusion phase. The extent of autophagy was assessed by the intracellular distribution of GFP-LC3 by fluorescence microscopy. The experiments were done at least three times and results shown are mean ± SEM

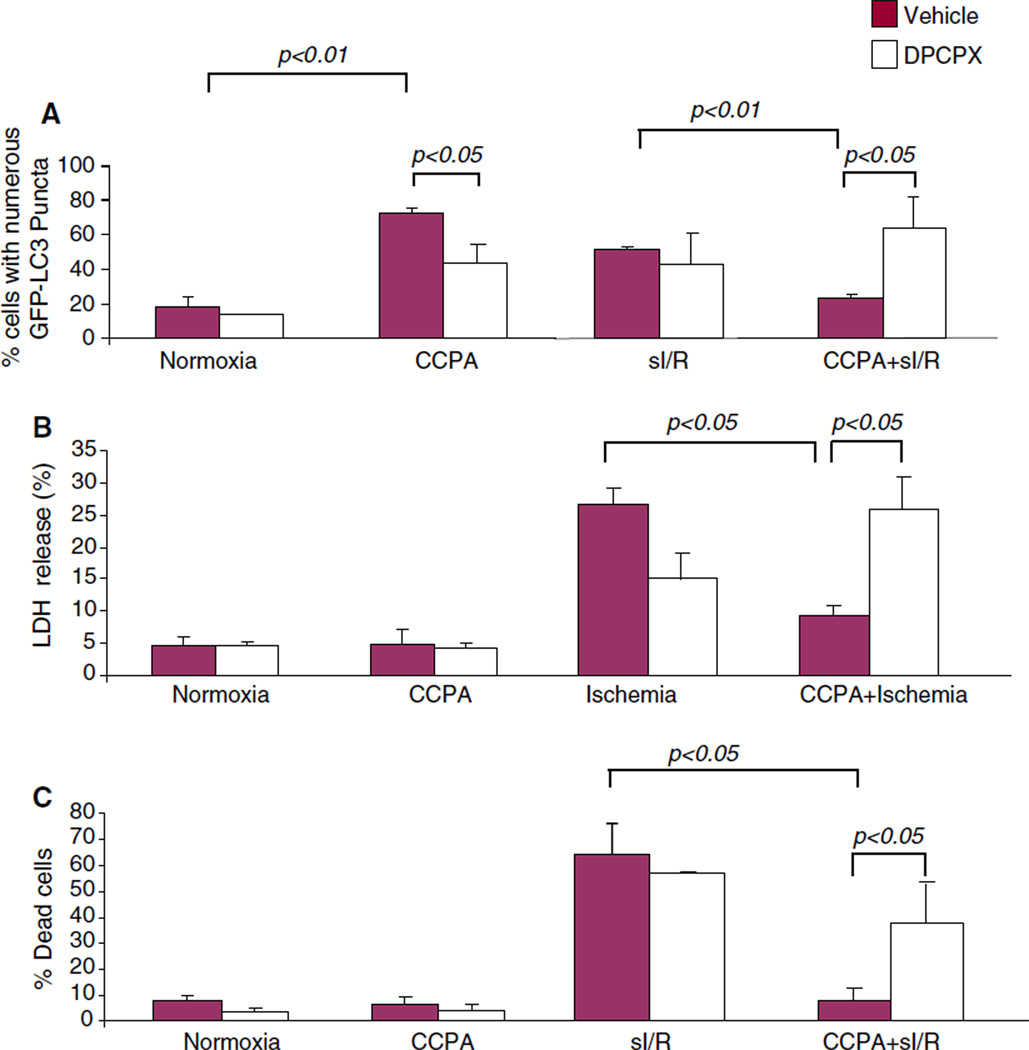

Receptor-selective effect of CCPA on autophagy and cytoprotection

To confirm that the effects of CCPA were mediated through the adenosine A1 receptor, HL-1 cells were treated with CCPA in the presence or absence of the A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX under conditions of normoxia or sI/R. As shown in Fig. 3, the upregulation of autophagy by CCPA under normoxic conditions was partially blocked by DPCPX. As expected, CCPA protected cells against sI/R as indicated by diminished LDH release and uptake of propidium iodide. Cytoprotection was abolished by DPCPX and the amount of autophagy during reperfusion, which we interpret to mean that there was more damage—hence more repair autophagy needed during reperfusion. These results suggest that the effects of CCPA on autophagy and cytoprotection are mediated through the adenosine A1 receptor.

Fig. 3.

Receptor-selective effect of CCPA on autophagy and cytoprotection. Adv-GFP-LC3 infected HL-1 cells were treated in full medium with the selective A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX for 30 min, followed by 100 nM CCPA for 10 min, and then cells were subjected to sI/R (2 h sI, 3 h R). The extent of autophagy was assessed by the intracellular distribution of GFP-LC3 by fluorescence microscopy (a), and cell death was measured by LDH release at the end of simulated ischemia (b) or by propidium iodide uptake at the end of reperfusion (c)

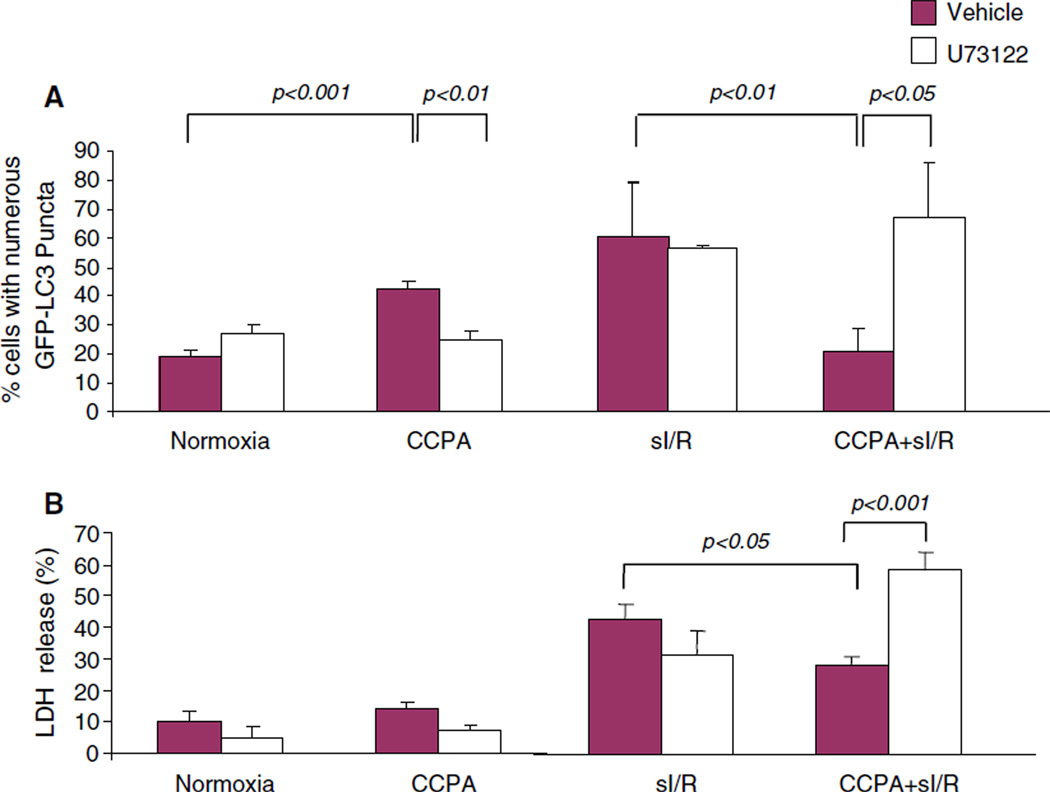

CCPA signals autophagy through PLC and a rise in intracellular calcium

The adenosine A1 receptor is a G-protein-coupled receptor that activates phospholipase C (PLC) [24]. To determine if PLC signaling was upstream of autophagy induction by CCPA, we used the PLC inhibitor U73122 and assessed effects on autophagy and cytoprotection. As shown in Fig. 4, PLC is required for CCPA stimulation of autophagy before ischemia; blockade of the CCPA signal through PLC results in an increase in autophagy after sI/R (repair autophagy) as well as an increase in LDH release at end of simulated ischemia.

Fig. 4.

CCPA signals autophagy through PLC. HL-1 cells infected with Adv-GFP-LC3 were treated with the PLC inhibitor U73122 (2 µM) for 15 min followed by CCPA for 10 min, then incubated in normoxic conditions or subjected to sI/R (2 h sI, 3 h R). Autophagy was scored by fluorescence microscopy (a). The amount of LDH released to the medium was determined immediately after ischemia and compared to the total activity of control homogenate (100%) (b)

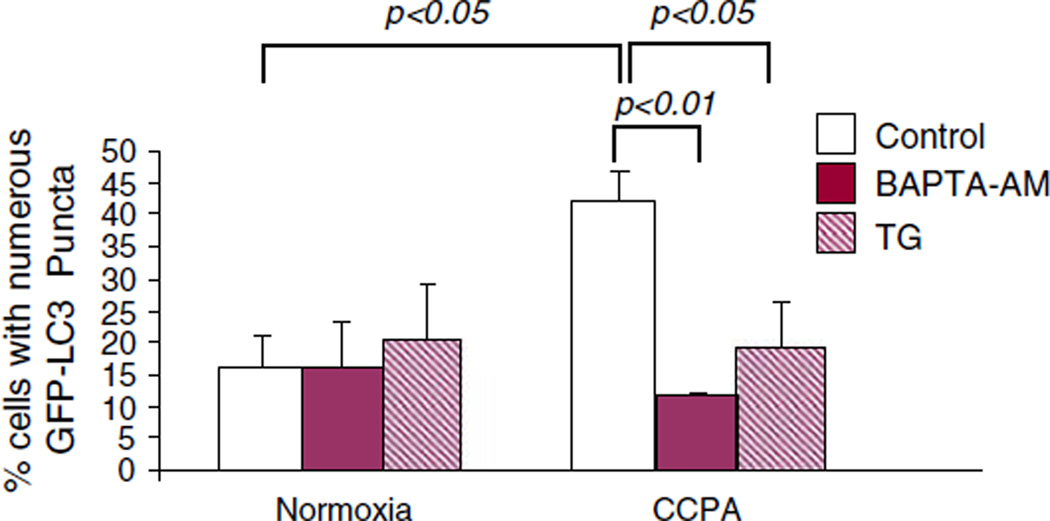

Autophagy (induced by starvation or rapamycin) is dependent upon on the release of calcium from the sarco-endoplasmic reticulum (S/ER) [25] as is adenosine preconditioning [26]. As shown in Fig. 5, we confirmed that chelation of cytoplasmic calcium with BAPTA-AM, or depletion of S/ER calcium stores by thapsigargin pre-treatment, suppressed the induction of autophagy by CCPA, suggesting a convergence of the two processes. This is consistent with our previous findings that starvation-induced autophagic flux is also suppressed by BAPTA or thapsigargin [25].

Fig. 5.

CCPA signals autophagy through a rise in intracellular calcium. HL-1 cells were treated with 1 µM thapsigargin (TG) or 25 µM BAPTA-AM for 15 min followed by CCPA for 10 min. The cells were washed in PBS and fixed and the intracellular distribution of GFP-LC3 was assessed by fluorescence microscopy

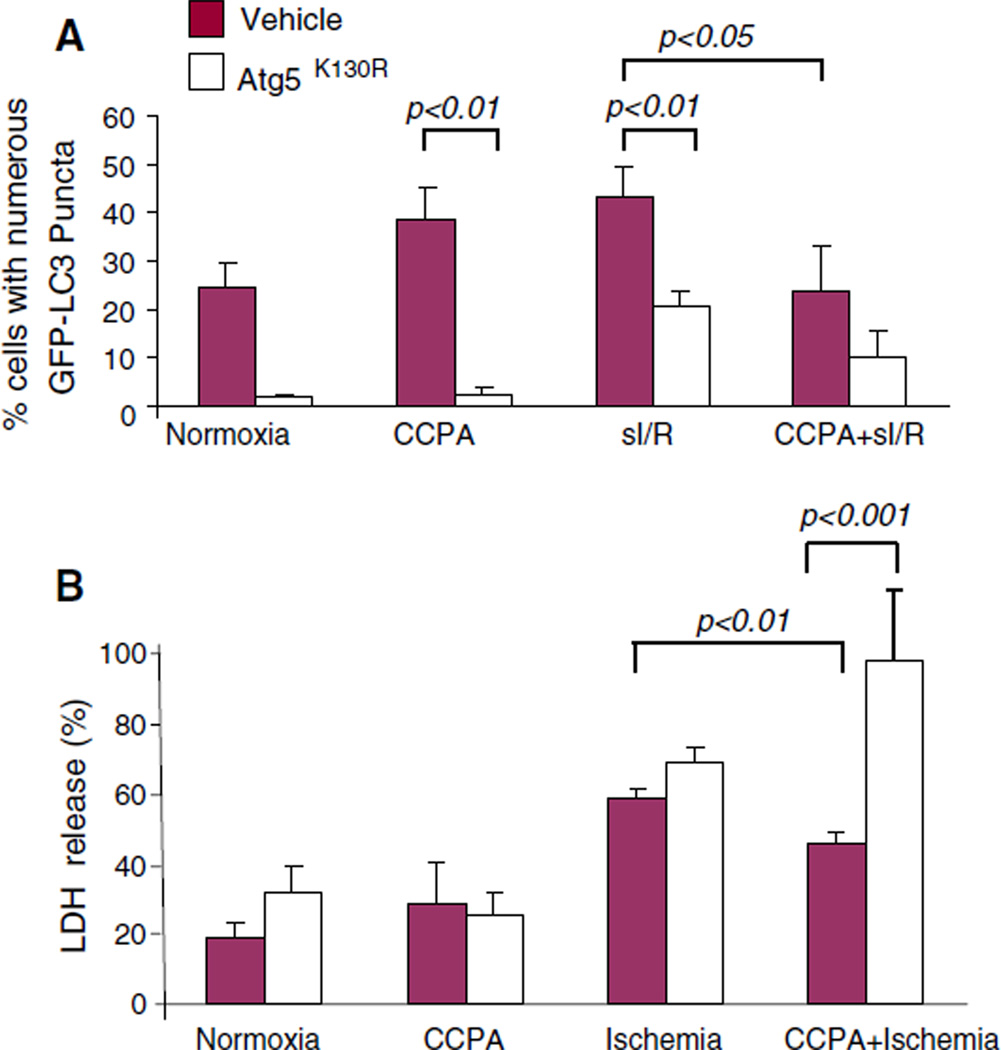

Cytoprotection by CCPA is dependent upon autophagy

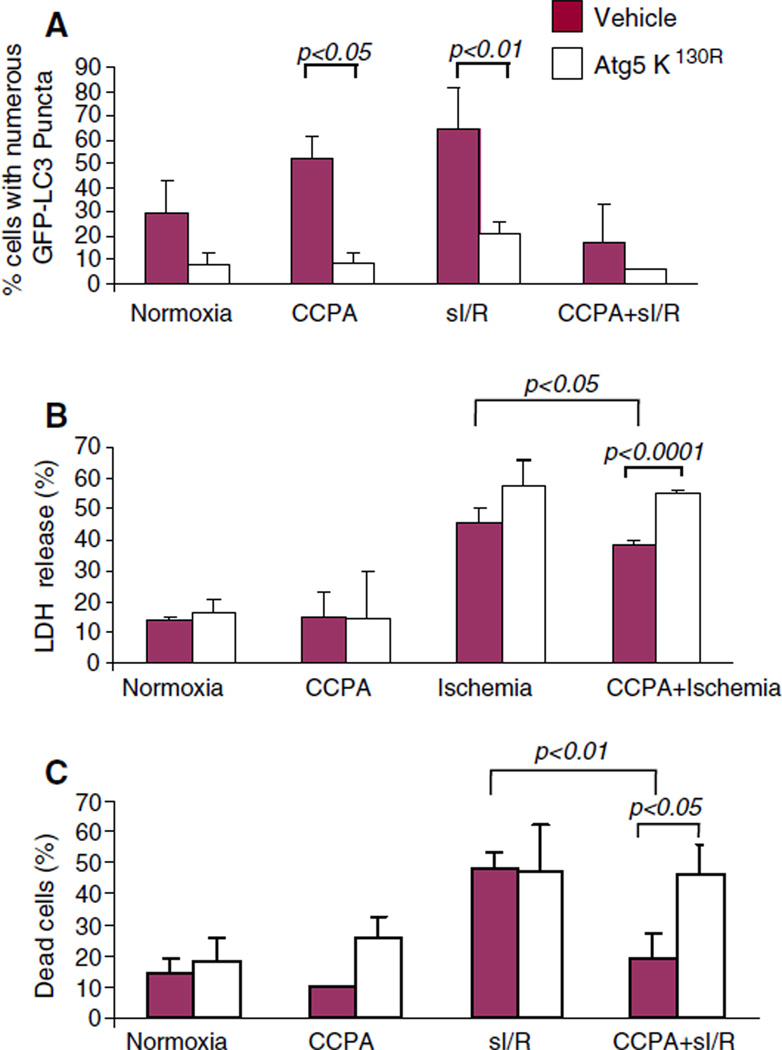

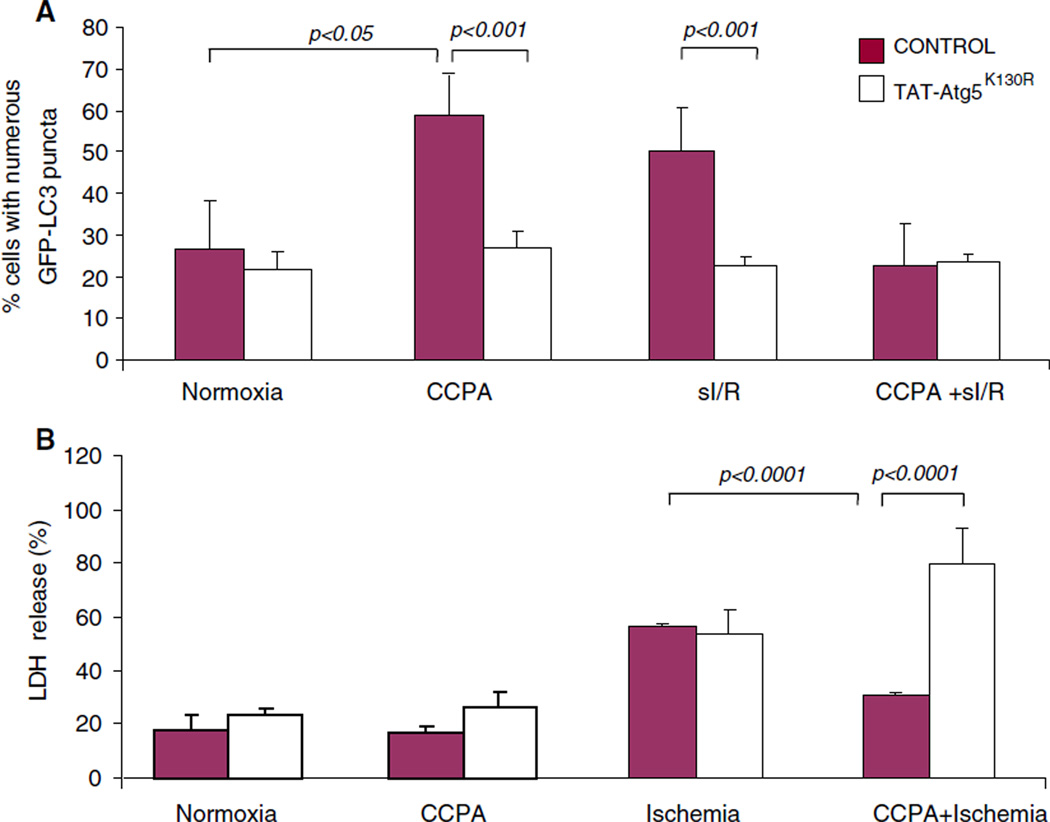

The foregoing results were consistent with the notion that the CCPA-mediated induction of autophagy before sI/R was cytoprotective and resulted in a diminished need for autophagy after sI/R. We have previously shown that mitochondrial damage induces autophagy as part of a repair response [11, 27]. To determine whether autophagy is required for protection mediated by CCPA, we transfected HL-1 cells with a dominant negative inhibitor of autophagy (Atg5K130R) or with empty vector. We confirmed that Atg5K130R effectively suppressed autophagy (Fig. 6). Importantly, the dominant negative inhibitor of autophagy eliminated the protective effects of CCPA after sI/R. Direct suppression of autophagy was not cytoprotective, arguing against a deleterious role for autophagy, as has been suggested by some investigators. To further validate these findings, we performed this study in adult cardiomyocytes, using cell-permeable recombinant Tat-Atg5K130R to inhibit autophagy. As shown in Fig. 7, CCPA induced autophagy in adult cardiomyocytes and conferred cytoprotection. Administration of Tat-Atg5K130R suppressed autophagy and eliminated the protection by CCPA. It is important to note that inhibiting autophagy in the absence of CCPA did not increase LDH release under normoxic conditions nor did it exacerbate injury from sI/R, indicating that the recombinant protein is not directly cytotoxic. It also indicates that inhibiting autophagy is not protective in this cell culture model. These results provide clear and compelling evidence in support of the notion that CCPA mediates its cytoprotective effect through the induction of autophagy.

Fig. 6.

Cytoprotection by CCPA is dependent upon autophagy. HL-1 cells were co-transfected with GFP–LC3 and the dominant negative autophagy protein Atg5K130R. After 24 h cells were treated for 10 min with CCPA followed by sI/R (2 h sI, 3 h R). The extent of autophagy was assessed by the intracellular distribution of GFP-LC3 by fluorescence microscopy (a). Cytoprotection was assessed by measuring LDH released into the media at the end of ischemia (b) or by propidium iodide uptake (c)

Fig. 7.

Cytoprotection by CCPA requires autophagy in adult cardiomyocytes. Adult rat cardiomyocytes were infected with GFP-LC3 adenovirus for 2 h and washed with the plating medium. After 20 h, cells were incubated with or without Tat-Atg5K130R for 30 min followed by CCPA or vehicle for 10 min. Cells were subjected to normoxia or simulated ischemia followed by 2 h reperfusion, and autophagy was scored as the percentage of cells with numerous puncta (a). For determination of cell death, LDH release into the culture supernatant was measured at the end of simulated ischemia (b)

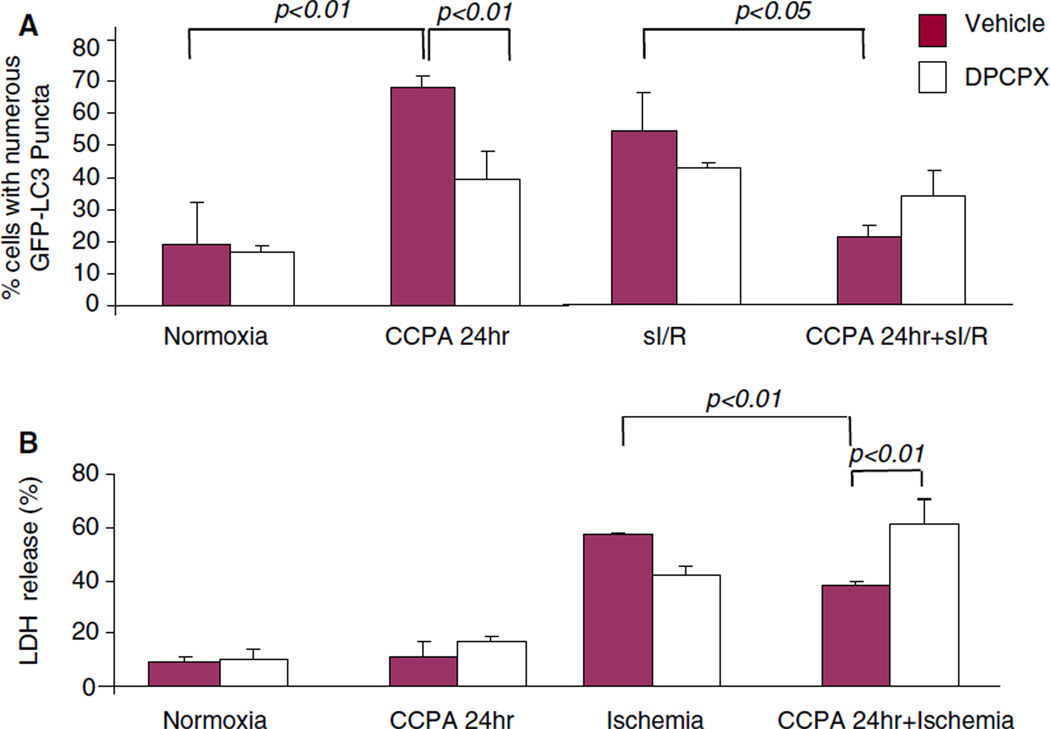

Effect of CCPA on delayed preconditioning

There are two windows of preconditioning: one is induced within minutes and lasts several hours, and the second window of protection is observed 16–24 h after the preconditioning stimulus (delayed or late phase). We treated HL-1 cells with CCPA for 10 min in the presence or absence of DPCPX, then 24 h later assessed autophagy and cytoprotection. As shown in Fig. 8, we found that autophagy is upregulated 24 h after treatment with CCPA; as previously noted for immediate preconditioning, the amount of repair autophagy seen at reperfusion is less in CCPA-treated cells, reflecting less damage. The A1 antagonist blocked the effects of CCPA on autophagy and also abolished the cytoprotection by CCPA in the second window of protection. To determine if autophagy was required for the second window of protection, we transfected HL-1 cells with Atg5K130R, the dominant negative inhibitor of autophagy. Atg5K130R suppressed autophagy in the second window of protection and abolished the cytoprotective effect of CCPA (Fig. 9). Taken together, these results indicate that CCPA mediates delayed preconditioning by a mechanism that requires autophagy.

Fig. 8.

Receptor-selective stimulation of autophagy in delayed preconditioning. GFP–LC3 infected HL-1 cells were treated with the selective A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX for 30 min prior to CCPA exposure for 10 min followed by washout. After 24 h, the cells were exposed to sI/R (2 h sI, 3 h R). The cells were fixed, and the extent of autophagy was assessed by the intracellular distribution of GFP-LC3 by fluorescence microscopy in normoxia and after sI/R (a). Cell death was measured by LDH release at the end of ischemia (b)

Fig. 9.

Role of autophagy in delayed preconditioning. HL-1 cells were co-transfected with GFP–LC3 and dominant negative Atg5K130R. Cells were treated with CCPA for 10 min, followed by washout. 20 h later, cells were subjected to sI/R (2 h sI, 3 h R). The extent of autophagy was assessed by the intracellular distribution of GFP-LC3 by fluorescence microscopy (a) and cell death was measured by LDH release into the medium at the end of ischemia (b)

Discussion

The role of autophagy in the heart is controversial, with some findings suggesting it may be deleterious while other studies suggest a clear protective role. Ischemic and pharmacologic preconditioning are recognized as the most potent and reproducible cardioprotective interventions yet identified, but the precise intracellular mechanism remains elusive. Based on our previous observation that autophagy is upregulated during reperfusion and serves a cytoprotective role in HL-1 cells, we hypothesized that autophagy might represent a component of the mechanism of preconditioning. To test this, we relied on the HL-1 myocyte cell line, which we have evaluated in a number of studies and have found to behave nearly identically to neonatal rat cardiomyocytes with respect to the autophagic response to sI/R [1], hydrogen peroxide [28], lipopolysaccharide [28], and pharmacologic preconditioning agents including CCPA. We also showed for the first time that CCPA upregulated autophagy in adult rat cardiomyocytes and in vivo in αMHC-mCherry-LC3 transgenic mice.

In HL-1 cells, we found that CCPA upregulated autophagy within 10 min, and conferred cytoprotection against sI/R in the same time frame. Interestingly, the amount of autophagy observed during the reperfusion phase was less than in untreated cells subjected to sI/R. This seemingly paradoxical effect can be explained if one considers autophagy part of a repair response. In preconditioned cells, less damage occurs during ischemia, so less repair autophagy is required during the reperfusion phase. If CCPA directly suppressed autophagy, one would expect it to suppress starvation-induced autophagy, but in that setting, it has no effect. Previous studies examining the abundance of autophagosomes in tissue have failed to take into account the turnover of these transient organelles. However, an increase in autophagosomes could be due to increased production or diminished clearance through the lysosomal pathway. We used comparisons of autophagy in the absence (steady-state) and presence (cumulative) of bafilomycin A1, which prevents autophagosome-lysosome fusion, in order to assess flux. Notably, the increase in autophagy observed after sI/R is largely due to impaired clearance (no increase in the presence of Baf). CCPA increases flux before sI/R, but appears to diminish autophagosome formation after sI/R without improving clearance (no increase after Baf).

Adenosine receptor signaling has been studied extensively and a variety of selective agonists and antagonists have been developed. CCPA is generally regarded as an A1-selective agonist, and DCPCX an A1-selective antagonist. We confirmed that the effects of CCPA on autophagy and on cytoprotection were mediated through the A1 receptor. We also confirmed that the downstream activation of phospholipase C and release of S/ER Ca+2 were required for the effects on autophagy and cytoprotection.

Previous efforts to understand the role of autophagy in the heart have used Atg5(−/−) mice or Beclin1(+/−) mice. The Atg5(−/−) mice develop a dilated cardiomyopathy, suggesting that autophagy plays an important role in normal cardiac homeostasis. The Beclin1(+/−) mice have diminished autophagy, and a previous study by Sadoshima’s group indicated that these mice had smaller infarcts than their wild type littermates [29]. However, this result must be interpreted with caution. It is unknown whether other compensatory pathways are upregulated in these animals; for instance, Atg5(−/−) mice show upregulation of ERK phosphorylation that is the basis for cytoprotection [30]. Furthermore, Beclin1 contains a BH3 domain which is postulated to function as a pro-apoptotic molecule. Reduction in the abundance of a proapoptotic protein may confer protective benefit independent of effects of autophagy. However, autophagy may not be universally protective, and its connection to innate immunity implies that perturbations to autophagy (up or down) may have pleiotropic effects [28, 31, 32].

As noted earlier, pharmacologic inhibitors of autophagy (3-MA and wortmannin) are nonspecific and may lead to confounding results. To overcome these concerns, we used a dominant negative inhibitor of autophagy, Atg5K130R. We found that transient transfection of Atg5K130R potently reduced autophagy and blocked the cytoprotective effect of CCPA in HL-1 cells subjected to sI/R. In the present study, cell death after sI/R was not increased by Atg5K130R, in contrast to our previous findings [1]. However, the studies differ with respect to readout (LDH release of both transfected and non-transfected cells versus Bax translocation scored only in transfected cells), and sensitivity (detection of small differences in cell viability is better in the Bax assay). However, the present results suggest that operational autophagy may not be essential to the basal/innate resilience to cardiomyocyte ischemia, but is important to the enhanced cytoprotection mediated by CCPA.

CCPA also elicits delayed preconditioning; we found upregulation of autophagy at 24 h after a 10 min exposure to CCPA followed by washout. The effects on autophagy and cytoprotection against sI/R were receptor dependent, as they were blocked by DPCPX. The protective effects of CCPA in delayed preconditioning also depended on autophagy, as suppression of autophagy by Atg5K130R abolished the cytoprotection.

Further studies will be necessary to determine whether other preconditioning agents also elicit autophagy, and whether autophagy is universally required for cardioprotection. These studies are based on pre-treatment; thus it is not yet clear whether autophagy plays a protective role during reperfusion. However, evidence supports the notion that the effects of preconditioning are mediated during reperfusion [33]. Postconditioning appears to involve the same signaling pathways as preconditioning [34, 35]. Although we have shown that CCPA induces autophagy in the hearts of mCherry-LC3 mice, additional studies are necessary to elucidate the role of autophagy in vivo, as well as to determine why autophagy is protective. However, the present study demonstrates, for the first time, that autophagy serves as a key mediator of protection by the adenosine A1 receptor agonist CCPA. We suggest that interventions which directly target autophagy may represent new therapeutic modalities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants P01HL85577, R01HL060590, R01AG033283 (to RAG), R01 HL087023 (to ABG), and R01HL034579 (to RMM).

Footnotes

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Contributor Information

Smadar Yitzhaki, BioScience Center, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, CA 92182-4650, USA.

Chengqun Huang, BioScience Center, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, CA 92182-4650, USA.

Wayne Liu, BioScience Center, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, CA 92182-4650, USA.

Youngil Lee, BioScience Center, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, CA 92182-4650, USA.

Åsa B. Gustafsson, BioScience Center, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, CA 92182-4650, USA

Robert M. Mentzer, Jr, Email: rmentzer@med.wayne.edu, School of Medicine, WSU Cardiovascular Research Institute, Wayne State University, 540 E. Canfield 1241 Scott Hall, Detroit, MI 48201, USA.

Roberta A. Gottlieb, Email: robbieg@sciences.sdsu.edu, BioScience Center, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, CA 92182-4650, USA.

References

- 1.Hamacher-Brady A, Brady NR, Gottlieb RA. Enhancing macroautophagy protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(40):29776–29787. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603783200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MV, Downey JM. Adenosine: trigger and mediator of cardioprotection. Basic Res Cardiol. 2008;103(3):203–215. doi: 10.1007/s00395-007-0687-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Downey JM, Krieg T, Cohen MV. Mapping preconditioning’s signaling pathways: an engineering approach. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1123:187–196. doi: 10.1196/annals.1420.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao Z, Gross GJ. A comparison of adenosine-induced cardioprotection and ischemic preconditioning in dogs. Efficacy, time course, and role of KATP channels. Circulation. 1994;89(3):1229–1236. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.3.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fryer RM, Eells JT, Hsu AK, Henry MM, Gross GJ. Ischemic preconditioning in rats: role of mitochondrial K(ATP) channel in preservation of mitochondrial function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278(1):H305–H312. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.1.H305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa AD, Garlid KD. Intramitochondrial signaling: interactions among mitoKATP, PKCepsilon, ROS and MPT. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295(2):H874–H882. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01189.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Dorado D, Rodriguez-Sinovas A, Ruiz-Meana M, Inserte J, Agullo L, Cabestrero A. The end-effectors of preconditioning protection against myocardial cell death secondary to ischemia-reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70(2):274–285. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caro LHP, Plomp PJAM, Wolvetang EJ, Kerkhof C, Meijer AJ. 3-Methyladenine, an inhibitor of autophagy, has multiple effects on metabolism. Eur J Biochem. 1988;175(2):325–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sekulic A, Hudson CC, Homme JL, Yin P, Otterness DM, Karnitz LM, Abraham RT. A direct linkage between the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-AKT signaling pathway and the mammalian target of Rapamycin in mitogen-stimulated and transformed cells. Cancer Res. 2000;60(13):3504–3513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizushima N, Noda T, Yoshimori T, Tanaka Y, Ishii T, George MD, Klionsky DJ, Ohsumi M, Ohsumi Y. A protein conjugation system essential for autophagy. Nature. 1998;395(6700):395–398. doi: 10.1038/26506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamacher-Brady A, Brady NR, Logue SE, Sayen MR, Jinno M, Kirshenbaum LA, Gottlieb RA, Gustafsson AB. Response to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury involves Bnip3 and autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2006;14:146–157. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pyo J-O, Jang M-H, Kwon Y-K, Lee H-J, Jun J-IL, Woo H-N, Cho D-H, Choi B, Lee H, Kim J-H, Mizushima N, Oshumi Y, Jung Y-K. Essential roles of Atg5 and FADD in autophagic cell death: DISSECTION OF AUTOPHAGIC CELL DEATH INTO VACUOLE FORMATION AND CELL DEATH. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(21):20722–20729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413934200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Decker RS, Wildenthal K. Lysosomal alterations in hypoxic and reoxygenated hearts. I. Ultrastructural and cytochemical changes. Am J Pathol. 1980;98(2):425–444. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T, Kominami E, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. Embo J. 2000;19(21):5720–5728. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan L, Vatner DE, Kim SJ, Ge H, Masurekar M, Massover WH, Yang G, Matsui Y, Sadoshima J, Vatner SF. Autophagy in chronically ischemic myocardium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(39):13807–13812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506843102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Claycomb WC, Lanson NA, Jr, Stallworth BS, Egeland DB, Delcarpio JB, Bahinski A, Izzo NJ., Jr HL–1 cells: a cardiac muscle cell line that contracts and retains phenotypic characteristics of the adult cardiomyocyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(6):2979–2984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Becker-Hapak M, McAllister SS, Dowdy SF. TAT-mediated protein transduction into mammalian cells. Methods. 2001;24(3):247–256. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gustafsson AB, Sayen MR, Williams SD, Crow MT, Gottlieb RA. TAT protein transduction into isolated perfused hearts: TAT-apoptosis repressor with caspase recruitment domain is cardioprotective. Circulation. 2002;106(6):735–739. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000023943.50821.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto A, Tagawa Y, Yoshimori T, Moriyama Y, Masaki R, Tashiro Y. Bafilomycin A1 prevents maturation of autophagic vacuoles by inhibiting fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes in rat hepatoma cell line, H-4-II-E cells. Cell Struct Funct. 1998;23(1):33–42. doi: 10.1247/csf.23.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Ani D, Jacobson KA, Shainberg A. Characterization of adenosine receptors in intact cultured heart cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;48(4):727–735. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90050-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Safran N, Shneyvays V, Balas N, Jacobson KA, Nawrath H, Shainberg A. Cardioprotective effects of adenosine A1 and A3 receptor activation during hypoxia in isolated rat cardiac myocytes. Mol Cell Biochem. 2001;217(1–2):143–152. doi: 10.1023/a:1007209321969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nieminen A-L, Gores GJ, Bond JM, Imberti R, Herman B, Le-masters JJ. A novel cytotoxicity screening assay using a multiwell fluorescence scanner. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1992;115(2):147–155. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(92)90317-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwai-Kanai E, Yuan H, Huang C, Sayen MR, Perry-Garza CN, Kim L, Gottlieb RA. A method to measure cardiac autophagic flux in vivo. Autophagy. 2008;4(3):322–329. doi: 10.4161/auto.5603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ethier MF, Madison JM. Adenosine A1 receptors mediate mobilization of calcium in human bronchial smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35(4):496–502. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0290OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brady NR, Hamacher-Brady A, Yuan H, Gottlieb RA. The autophagic response to nutrient deprivation in the HL-1 cardiac myocyte is modulated by Bcl-2 and sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium stores. FEBS J. 2007;274(12):3184–3197. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mubagwa K. Does adenosine protect the heart by acting on the sarcoplasmic reticulum? Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53(2):286–289. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00550-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamacher-Brady A, Brady NR, Gottlieb RA, Gustafsson AB. Autophagy as a protective response to Bnip3-mediated apoptotic signaling in the heart. Autophagy. 2006;2(4):307–309. doi: 10.4161/auto.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuan H, Perry CN, Huang C, Iwai-Kanai E, Carreira RS, Glembotski CC, Gottlieb RA. LPS-induced autophagy is mediated by oxidative signaling in cardiomyocytes and is associated with cytoprotection. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;296(2):H470–H479. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01051.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takagi H, Matsui Y, Hirotani S, Sakoda H, Asano T, Sadoshima J. AMPK mediates autophagy during myocardial ischemia in vivo. Autophagy. 2007;3(4):405–407. doi: 10.4161/auto.4281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sivaprasad U, Basu A. Inhibition of ERK attenuates autophagy and potentiates tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced cell death in MCF-7 cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12(4):1265–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00282.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valeur HS, Valen G. Innate immunity and myocardial adaptation to ischemia. Basic Res Cardiol. 2009;104(1):22–32. doi: 10.1007/s00395-008-0756-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saitoh T, Fujita N, Jang MH, Uematsu S, Yang BG, Satoh T, Omori H, Noda T, Yamamoto N, Komatsu M, Tanaka K, Kawai T, Tsujimura T, Takeuchi O, Yoshimori T, Akira S. Loss of the autophagy protein Atg16L1 enhances endotoxin-induced IL-1beta production. Nature. 2008;456(7219):264–268. doi: 10.1038/nature07383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hausenloy DJ, Wynne AM, Yellon DM. Ischemic preconditioning targets the reperfusion phase. Basic Res Cardiol. 2007;102(5):445–452. doi: 10.1007/s00395-007-0656-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mykytenko J, Reeves JG, Kin H, Wang NP, Zatta AJ, Jiang R, Guyton RA, Vinten-Johansen J, Zhao ZQ. Persistent beneficial effect of postconditioning against infarct size: role of mitochondrial K(ATP) channels during reperfusion. Basic Res Cardiol. 2008;103(5):472–484. doi: 10.1007/s00395-008-0731-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sivaraman V, Mudalagiri NR, Di Salvo C, Kolvekar S, Hayward M, Yap J, Keogh B, Hausenloy DJ, Yellon DM. Postconditioning protects human atrial muscle through the activation of the RISK pathway. Basic Res Cardiol. 2007;102(5):453–459. doi: 10.1007/s00395-007-0664-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]