Abstract

Oxygen is necessary for life yet too much or too little oxygen is toxic to cells. The oxygen tension in the maternal plasma bathing placental villi is <20 mm Hg until 10–12 weeks’ gestation, rising to 40–80 mmHg and remaining in this range throughout the second and third trimesters. Maldevelopment of the maternal spiral arteries in the first trimester predisposes to placental dysfunction and sub-optimal pregnancy outcomes in the second half of pregnancy. Although low oxygen at the site of early placental development is the norm, controversy is intense when investigators interpret how defective transformation of spiral arteries leads to placental dysfunction during the second and third trimesters. Moreover, debate rages as to what oxygen concentrations should be considered normal and abnormal for use in vitro to model villous responses in vivo. The placenta may be injured in the second half of pregnancy by hypoxia, but recent evidence shows that ischemia with reoxygenation and mechanical damage due to high flow contributes to the placental dysfunction of diverse pregnancy disorders. We overview normal and pathologic development of the placenta, consider variables that influence experiments in vitro, and discuss the hotly debated question of what in vitro oxygen percentage reflects the normal and abnormal oxygen concentrations that occur in vivo. We then describe our studies that show cultured villous trophoblasts undergo apoptosis and autophagy with phenotype-related differences in response to hypoxia.

Keywords: Oxygen, Trophoblasts, Apoptosis, Autophagy

1. Introduction

Oxygen is a necessity for life, yet is toxic to cells when dysregulated. The human placenta develops initially in a low oxygen environment with an ambient pO2 < 20 mm Hg [1]. The low oxygen tension favors cell proliferation and angiogenesis in the placenta and organogenesis in the embryo. Oxygen tension then rises when the intervillous circulation is established at about 10–12 weeks’ gestation. The placenta adapts to the changing oxygen levels that support normal placental function and fetal development by modulation of hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF 1α) and by increasing cellular antioxidant defenses [2]. Aberrations in the normal modification of the spiral arteries predisposes placental villi to high oxygen tension, hypoxia, hypoxia-reoxygenation, and mechanical injury in different stages of pregnancy, all of which are implicated in pregnancy complications that range from miscarriage to pre-eclampsia [3]. This complex relationship between oxygen and the placenta presents major challenges to investigators who use in vitro models to dissect placental biology. We provide an overview of normal placental development, describe the phenotypic characteristics resulting from aberrant development and highlight controversies related to the oxygen levels for in vitro models used to study placental biology. Finally, we review the regulation of apoptosis and autophagy in human trophoblast exposed to hypoxia and the phenotype specific responses that likely enhance placental survival in vivo.

2. Normal placental development

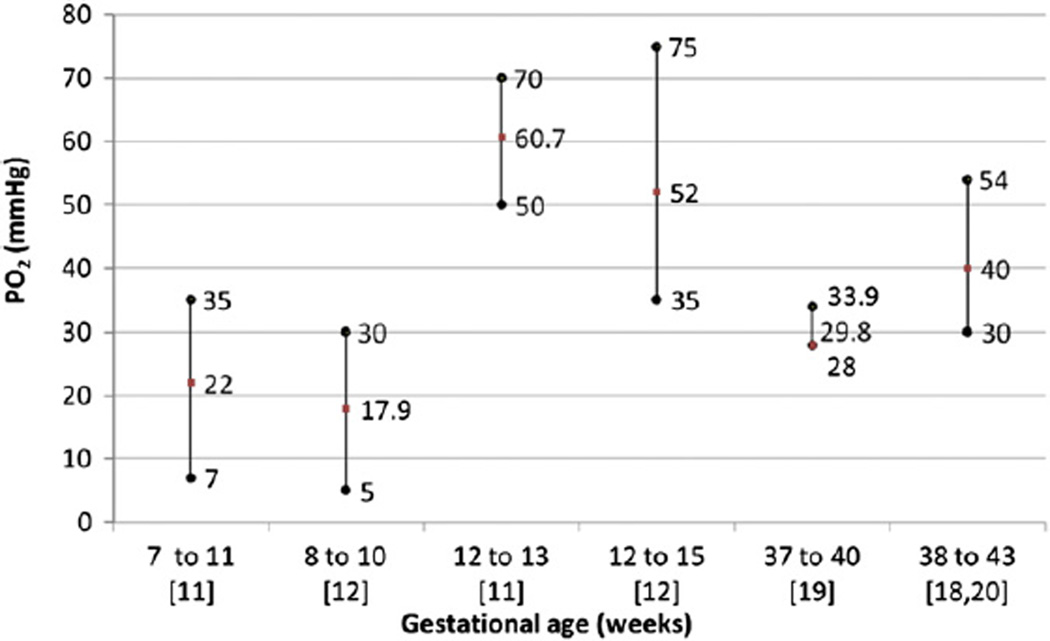

The human embryo undergoes interstitial implantation by invading the maternal decidua at the blastocyst stage [4]. Differentiation of the trophectoderm yields multiple cell lineages including extravillous and villous trophoblasts. The former invade and remodel maternal spiral arteries, modifying the vascular smooth muscle to dilate the spiral arterioles. Although placental villi are eventually bathed in maternal blood in the hemochorial placenta [5], prior to 10 weeks’ gestation maternal blood flow to the placenta is blocked by endovascular plugs of extravillous trophoblasts [6–9]. Thus, early placental and embryonic development occurs in a state of low oxygen, with nutrients supplied by maternal plasma and secretions from maternal endometrial glands called histiotroph [10]. Doppler studies confirm the absence of blood flow into the intervillous space prior to 10 weeks’ gestation in normal pregnancies, with in vivo measurements indicating pO2 <20 mmHg [11,12] (Fig. 1). Premature perfusion of this space during this first 10 weeks’ of development increases the risk of pregnancy loss [13], likely because of damaging effects of the excess reactive oxygen species.

Fig. 1.

Intervillous pO2 measurements in vivo. pO2 measurements depicted as means, minimum and maximum values in the intervillous space at different gestational ages from five in vivo studies. Studies are indicated in square brackets.

The low oxygen environment during early placental development is essential for normal placental angiogenesis, and this angiogenesis is promoted by hypoxia-induced transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of angiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor [14]. Notably, villi in the periphery of the developing placental disk receive blood flow first but this likely down regulates vasculogenesis because the villi in this location are avascular and are degraded in the mature placenta. Conversely, terminal villi of placentas in women at high altitude exhibit increased vascularization because of changes in action of blood vessel growth factors, with the degree of vascularization positively correlated with the reduction of maternal blood pO2 [15,16]. These studies underscore the key role that oxygen levels play in determining the vascular development of the villus.

Loss of the endovascular trophoblast plugs in the spiral arteries after 10–12 weeks’ gestation allows maternal blood to perfuse the intervillous space. Once intervillous blood flow is established, maternal blood delivers nutrients to the fetal circulation and allows the exchange of gases between the two circulations. The onset of blood flow is not a random process but instead is well orchestrated, progressing from the periphery-to-center of the placental disk, with villous regression in the placental periphery evolving into the chorion laeve [17]. The underlying mechanisms of these regulated events are poorly understood, but in part are related to differences in depth of trophoblast invasion that occurs across the decidua basalis in the placental bed, with superficial trophoblast invasion at the periphery and the deepest trophoblast invasion in the center of the placental disk [5]. The developing chorioallantoic villous trees are thereby exposed to a marked increase in pO2 in the range of 40–80 mmHg [18–20] (Fig. 1). The average oxygen tension in the intervillous space gradually declines from the second to the third trimester, reaching about 40 mm Hg in the third trimester as fetoplacental oxygen consumption increases [21].

2.1. Adaptations to changing oxygen tensions

There are two key placental adaptations that occur in response to the low oxygen in early pregnancy and evolve to cope with the increased oxygen levels beyond the first trimester. HIF-1α is a transcription factor and master regulator of the cellular response to oxygen levels [22], showing prominent expression in first trimester villi [23]. HIF-1a regulates the expression of genes required for cells to adapt to a low oxygen environment. HIF-1α may also regulate cellular proliferation and apoptosis by regulating genes such as p53, p21, and Bcl-2 [22,24].

Antioxidant enzymes play a key role in the response of trophoblast to the significant burst of oxidative stress that accompanies the initiation of intervillous space perfusion by maternal blood. The onset of intervillous blood flow in normal pregnancies is accompanied by an increase in expression of the inducible form of heat shock protein (HSP) 70, nitrotyrosine residues on proteins, and derangement of mitochondrial cristae in syncytiotrophoblast [17]. To cope with this burst of oxidative stress, the placenta employs a number of physiologic adaptations [25]. There are marked increases in mRNA levels and enzyme activities for the antioxidant enzymes catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and manganese and copper–zinc superoxide dismutase within placental tissues at the onset of intervillous blood flow. Teleologically, this response likely evolved as a defense mechanism to reduce harm to placental tissues exposed to this burst of oxidative stress [17].

3. The consequences of abnormal spiral arteriole development

Aberrations in normal developmental processes, including premature villous exposure to high levels of oxygen and deficient maternal spiral artery remodeling, are implicated in complications of pregnancy. The onset of intervillous circulation is premature and diffuse at the basal plate in pregnancies destined for miscarriage [17], and this premature perfusion associates with increased levels of oxidative stress, enhanced apoptosis, and a decrease in cell proliferation [26]. Histopathological changes in missed abortions include the presence of regressed villi to yield a thin shell around the chorionic sac, mimicking events at the periphery of the placenta where intervillous circulation evolves in normal pregnancies [25].

Recent evidence challenges the notion that chronic hypoxia per se is the etiologic factor in pregnancy complications such as fetal growth restriction (FGR) and pre-eclampsia. Placentas from high altitudes, which are exposed to oxygen tensions that have pO2’s in the 50–60 mm Hg range, are remarkably healthy and the pregnancies generally have normal outcomes without the histopathological lesions typical of placentas from pre-eclampsia [27]. The placentas from these women demonstrate lower levels of oxidative stress at baseline and in response to labor, when compared to sea level controls [28,29]. Indeed, labor during normal pregnancies has been used to investigate the in vivo consequences of intermittent flow into the intervillous space, as diastolic blood flow is interrupted in spiral arteries at the peak of uterine contractions [30]. After labor, placentas demonstrate many of the hallmarks of injury from hypoxia-reoxygenation, including increased lipid peroxidation and xanthine oxidase activity [31–33]. Similarly, placentas from women with pre-eclampsia show increased lipid peroxidation, xanthine oxidase activity and nitrative stress reflected by increased expression of nitrotyrosine residues [34,35]. Notably, gene array studies of placentas after labor reveal altered expression of genes in patterns that are strikingly similar to the changes in gene expression seen in pre-eclampsia [33,36,37].

Placental dysfunction may also result from mechanical injury to the villous tree due to the rheological consequences of excessive pressure of the blood flowing into the intervillous space in pregnancy complications such as early-onset pre-eclampsia and fetal growth restriction. As noted above, spiral artery remodeling in normal pregnancies results in high volume, low resistance blood flow into the intervillous space where the delicate trees of placental villi reside. In an elegant study using dimensions from the literature and mathematical modeling, Burton et al. found the major effect of spiral artery widening in normal pregnancies is to reduce the velocity of blood flow that enters the intervillous space [38]. The model showed a surprisingly modest impact on total blood flow. In the absence of proper spiral artery remodeling, the high velocity and turbulent flow is speculated to damage the villous architecture, rupturing anchoring villi and creating the cystic echogenic lesions seen by ultrasound in placentas with pathological pregnancies [38]. Taken together, these results suggest that the placental pathology associated with deficient spiral artery remodeling is the consequence of oxidative and nitrative stress and mechanical injury from turbulent, intermittent blood flow, rather than from chronic hypoxia.

4. Oxygen delivery and in vitro paradigms

A worthy goal for in vitro experiments is to use oxygen tensions that mimic the physiological environment for the given gestational age or that reproduce the conditions that might be present in pathological pregnancies. Three of the major obstacles that must be overcome to achieve these goals have been highlighted by Burton et al. [39] and include (1) the absence of hemoglobin as an oxygen carrier in vitro, (2) the identification of the actual in vivo oxygen concentration for a given gestational age and the reliable reproduction of this in vitro, and (3) the avoidance of oxidative stress that is inadvertently introduced during sample collection or culture [39]. We summarize below an excellent discussion on this topic by Zamudio [40], to address basic physiological principles underlying oxygen dynamics and to discuss challenges that arise during in vitro experiments.

In the absence of water vapor, the oxygen concentration in air is 21% so that the partial pressure of oxygen (pO2) at sea level is 0.21 × 760 mm Hg = 160 mm Hg [40]. Oxygen content is a useful parameter to describe in vivo conditions, as this integrates the pO2 with the capacity of carriers in a given medium to bind and transport oxygen. Importantly, the oxygen content is shown mathematically to depend largely on the concentration and capacity of oxygen carriers and less on the partial pressure of ambient oxygen [39,40].

The unique properties of hemoglobin allow this protein to deliver large quantities of oxygen to cells at relatively low oxygen tensions, and this physiology simply cannot be replicated in vitro. Investigators have used up to 95% O2 to compensate for the absence of hemoglobin to increase the amount of dissolved oxygen in culture medium [41,42]. However, the interplay between oxygen tension and dissolved oxygen, in the absence of an oxygen carrier, suggests that this approach results in a limited increase in the oxygen concentration [39,40]. Notably, this strategy risks rapid entry of oxygen into mitochondria, increasing formation of damaging reactive oxygen species.

Explants of villous tissues require special attention because oxygen must be delivered by diffusion from ambient gases into the culture medium and then into the multiple layers of the placental villi. To optimize oxygen delivery in vitro, samples may be maintained at the gas-medium interface, thereby minimizing the diffusion distance from the medium to the tissues [39]. Maintaining a constant flow of gases into the incubation chamber also maintains a consistent oxygen level in the gaseous phase. However, compared to cells directly exposed to the medium, cells within the connective tissue are more likely to experience low, and perhaps hypoxic, oxygen levels. We agree with Burton and colleagues [39] who recommend that explant samples be trimmed to a <5 mm maximal thickness to limit the potential for development of hypoxia in tissues.

The concentration of oxygen that is physiological for villi in vivo, and that should be mimicked in vitro, is hotly debated and unresolved. What is clear is that increasing the oxygen tension of the ambient atmosphere to levels that are higher than normally expected in maternal blood in pregnancy is likely detrimental. For example, Reti et al. [43] demonstrated that incubation of placental explants for 24 h in 95% oxygen reduces viability compared to 21% or 8% oxygen [43]. As we described above, in vivo measurements of the intervillous space show that although the pO2 may be as high as 80 mm Hg in the last two trimesters of pregnancy, it certainly does not approach the 160 mm Hg that would be predicted in medium in an ambient condition of either 95% or 21% oxygen. Clearly, 95% oxygen is toxic to cells in vitro and even 21% oxygen is deleterious for stem cells [44] and embryos [45] in culture. In practice, 2–3% oxygen for first trimester placentas and 5–8% for second and third trimester placentas are commonly used to mimic physiological oxygen conditions for gestational age. We suggest that a pragmatic approach is to use a humidified oxygen concentration of about 2% (pO2 about 15 mm Hg) for specimens from the first trimester [11,12] and 8% (pO2 about 60 mm Hg) for trophoblasts in the second or third trimester [21]. However, oxygen concentrations vary in different culture systems and may be substantially below or above the values predicted by the percentage oxygen in the atmosphere [46]. Moreover, the oxygen concentration in the pericellular region of the culture medium is often dramatically lower than predicted, as described below.

5. Villous and trophoblast responses to varying oxygen tensions in vitro

Table 1 summarizes some recent studies we and others have published on the phenotypic responses of placental tissue and primary trophoblasts under different oxygen conditions [43,47–60]. Taken together, these studies afford the following principles.

Table 1.

Summary of selected studies illustrating phenotypic expression of trophoblast under different oxygen conditions.

| Authors (year) | Placenta model | Oxygen concentrations |

Phenotypic expression Assays/measures | Key findings | Conclusions | Measured oxygen reported? |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levy et al. (2000) [47] |

Normal term PHTs |

1–2% ±EGF × 72 h 20% × 72 h |

Apoptosis | TUNEL, Bax, Bad, Bcl-2, p53 |

Exposure to hypoxia for 24 h enhanced apoptosis, accompanied by increased expression of p53 and Bax, and a decreased expression of Bcl-2. Addition of EGF and exposure of more differentiated trophoblasts to hypoxia significantly decreased apoptosis. |

Hypoxia enhances apoptosis in cultured trophoblasts by a mechanism that involves p53, Bax, and Bad. EGF and enhanced cell differentiation protect against hypoxia-induced apoptosis. |

No |

| Kilani et al. (2003) [48] |

Normal term primary CT |

Air (21%) × 24, 48, 96 h 5% × 2, 48, 96 h 2% × 24, 48, 96 h 0% × 24, 48, 96 h |

Apoptosis (constitutive and TNF-α-induced) |

TUNEL, M30 | Both constitutive and TNF-α apoptosis are highest at low (0%) or high (21%) oxygen. The ratio of constitutive to TNF-α induced apoptosis is constant from 2% to 21% oxygen. |

Induced apoptosis is insensitive to changes in oxygen levels except at the extremes of oxygen tension. Normal villous CT is remarkably resistant to hypoxia-induced apoptosis. |

Yes |

| Huppertz et al. (2003) [49] |

Late first trimester and term explants |

2%, 6%, 18% each × 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, 48, 72 h |

Proliferation Apoptosis Necrosis |

Histology Mib-1,Bcl-2 Activated caspase3 M30, TUNEL |

Low oxygen (2%) was associated with ST detachment and shedding, but increased CT proliferation. ST remained stable in 6% and 18% oxygen and CT proliferation was low. Activated caspase 3 and cleaved cytokeratin 18 were limited to CT in low oxygen (2%), while in 6% and 18% oxygen they were predominantly in ST. Similar results were noted in term as in late first trimester placentas. |

CT proliferation is inversely related to oxygen in tension. Low oxygen tension inhibits syncytial fusion. Severe placental hypoxia favors necrotic rather than apoptotic shedding of syncytial fragments into maternal circulation. |

Yes |

| Crocker et al. (2004) [50] |

Normal term explants |

3% × 1–11 days 17% ± TNF-a × 1–11 days |

Apoptosis Proliferation Necrosis Differentiation |

Apoptotic morphology, caspase 3, Mib-1, LDH, hCG |

Explants under 17% oxygen with and without TNF-α showed progressive degeneration of ST (days 0—2) followed by restoration of hCG (days 4—8) In 3% oxygen, ST showed similar degeneration with no hCG restoration but increased CT proliferation. Early apoptosis occurred in the ST while late apoptosis was localized to non-ST. Prolonged exposure to TNF-α increased ST apoptosis and necrosis while 3% oxygen had no effect. |

TNF-α enhances ST decline under 17% oxygen. 3% oxygen and TNF-α are associated with reduced CT differentiation and a shift towards proliferation. |

Yes |

| Crocker et al. (2004) [51] |

Normal, PE, and IUGR term explants |

3% × 1–11 days 17% ± TNF-a × 1–11 days |

Apoptosis Proliferation Necrosis Differentiation |

Apoptotic morphology, caspase 3,Mib-1, LDH, hCG |

Explants under 17% oxygen with TNF-α showed progressive degeneration of ST followed by restoration of hCG, which was significantly increased in PE and IUGR explants. In 3% oxygen, ST showed degeneration with no regeneration. Exaggerated cell death in explants from PE and IUGR exposed to 3% oxygen or TNF-α, with cell death predominantly apoptotic in PE and necrotic in IUGR explants. |

TNF-α enhances ST decline under 17% oxygen. 3% oxygen results in exaggerated cell death in PE via apoptosis and IUGR via necrosis, but promotes cell proliferation in normal explants. |

Yes |

| James et al. (2006) [52] |

Normal first trimester (8–12 weeks) explants |

1.5% × 5 days 8% × 5 days |

Outgrowth | Phase-contrast microscopy | 1.5% oxygen reduced the frequency and area of outgrowth compared to 8% oxygen. Outgrowth declined as gestational age increased from 8 to 12 weeks, independent of oxygen concentration. Differential response of outgrowth to oxygen was noted <11 weeks, but not ≥12 weeks. |

Oxygen and gestational age both regulate EVT outgrowth in the first trimester. |

Yes |

| Heazell et al. (2007) [53] |

Normal, PE, and IUGR term explants |

1% × 4 days 6% × 4 days 6% × 48 h → +H2O2 × 6 h 20% × 4 days |

Syncytial knots | Number and morphology of syncytial knots. Bcl-2, Mdm2, XIAP, survivin |

Syncytial knots increased in the presence of hypoxia or ROS. With few exceptions, morphology of syncytial knots in explants was similar to those in vivo in PE and IUGR. No loss of anti-apoptotic proteins in the regions of the syncytial knots. |

Increased syncytial knots in vivo in PE and IUGR can be replicated in vitro by hypoxia and ROS. |

Yes |

| Reti et al. (2007) [43] |

Normal term explants |

8% × 3, 6, 24 h 21% × 3, 6, 24 h 95% × 3, 6, 24 h |

Viability Metabolism Necrosis Apoptosis |

Glucose consumption, lactate production., M30, LDH, PTHrP, TNF-α, and 8- isoprostane |

95% and 21% oxygen (to a lesser extent) are associated with increased rates of glucose consumption and lactate production, increased LDH release, and increased cleaved cytokeratin 18, PTHrP, TNF-α, 8-isoprostane. |

Hyperoxia activates pathways and mechanisms involved in cellular metabolism, necrosis, and apoptosis. |

Yes |

| Cindrova-Davies et al. (2007) [54] |

Normal term explants |

10% × 7, 16 h 0.5% ×1h→ 10% × 6, 15 h |

Oxidative stress Inflammation Apoptosis |

HSP 27, HSP 90, HNE, p38, SAPK, NF-kB, TNF-α, cleaved caspases 3 and 9, IL-1, COX-2 |

H/R increased oxidative stress and activates the p38 MAPK and NF-kB pathways with down stream effects of increased TNF-α, COX-2, IL-1b and apoptosis. Vitamin C and E blocked these effects. |

Oxidative stress is a potent inducer of placental synthesis and release of proinflammatory factors, mediated mostly through the p38 MAPK and NF- KB pathways that is effectively blocked by vitamins C and E. |

No |

| Seeho et al. (2008) [55] |

Normal first trimester (11–14 weeks) explants |

3% × 1–8 days 20% × 1–8 days 3% → air (21%, 30 min) × 1–8 days |

Outgrowth Migration |

Phase-contrast microscopy | Lower number and extent of tropho blast outgrowth and migration in 3% compared to 20% oxygen. H/R further reduced outgrowth and migration. |

Placental villi and EVT in the late first trimester are sensitive to oxygen levels. Hypoxia and H/R inhibit outgrowth and migration of late first trimester EVT. |

Yes |

| Biron-Shental et al. (2008) [56] |

Normal term PHTs |

<1% × 4, 8, 24, 48 h 8% × 4, 8, 24, 48 h 20% × 4, 8, 24, 48 h CoCl2 DMOG |

Follistatin-like 3 expression |

FSTL3 | When compared to culture in 20% or 8%, PHTs in <1% oxygen exhibited a 4–6 fold increase in FSTL3 mRNA within 4 h. While intracellular FSTL3 protein was unchanged, hypoxia increased the level of FSTL3 in the medium. Exposure of PHT cells to the hypoxia- mimetic, CoCl2 , or proline hydroxylase inhibitor, DMOG, upregulated expression of FSTL3. |

Hypoxia enhances the expression of FSTL3 and its release from PHT cells. The finding that hypoxia-mimetic agents enhance FSTL3 expression implicates HIF-1α in this process. |

No |

| Heazell et al. (2008) [57] |

Normal term explants |

1% × 96 h 6% × 96 h 20% × 96 h |

Placental metabolome |

Metabolites in conditioned cultured media (CCM) and tissue lysates by gas-chromatograph-mass spectroscopy |

Metabolic differences were identified between samples cultured in 1, 6 and 20% oxygen in both CCM and tissue lysates. Differentially expressed metabolites included 2-deoxyribose, threitol or erythritol and hexadecanoic acid. |

Metabolomic strategies offer a novel approach to investigate placental function. |

No |

| Rampersad et al. (2008) [58] |

Normal term PHTs. Normal, PE, and IUGR placentas for IF and IHC |

<1% ± active complement × 24, 72 h 8% ± active complement × 24, 72 h 20% ± active complement × 24, 72 h |

Villous injury and C5b-9/MAC interaction |

MAC binding to trophoblasts PARP, M30, hCG, syncytin. Syncytia formation |

MAC localized to fibrin deposits in normal placentas, and especially in placentas from PE and IUGR. MAC binding to CT was inversely proportional to oxygen concentration and enhanced apoptosis. MAC increased markers of differentiation in PHT cultures at 72 h. |

Complement activity, as assessed by MAC, associates with fibrin deposits at sites of villous injury in vivo. Hypoxia enhances MAC deposition in cultured CT. MAC alters trophoblast function in a phenotype specific manner, increasing apoptosis in CT with little or no effect in ST. |

No |

| Blankley et al. (2010) [59] |

Normal term explants |

1% × 4 days 6% × 4 days |

Protein secretion | Proteomic analysis of culture medium IL-8 assay |

Of 499 proteins identified in the culture medium, 22 were potentially up- and 41 down-regulated under hypoxia. IL-8 up-regulation under hypoxia was validated by antibody-based ELISA. |

Changes in global protein secretion are suggestive of decreased extracellular matrix remodeling under hypoxia. |

No |

| Chen et al. (2010) [60] |

Normal term PHTs (ST at 52 h of culture) |

20% or <1% oxygen × ≥ 24 h, in the presenc or absence of staurosporine or the p53 modulators nutlin-3, pifithrin-α, and pifithrin-µ |

Effect of hypoxia e on p53-mediated apoptosis in ST |

M30, PARP, Mdm2, Mdmx, p53, Bad and immunofluorescence for E-cadherin and p53 |

Compared with 20% oxygen, exposure of ST to <1% oxygen upregulated HIF-1α and down-regulated p53. Activity of p53 in hypoxic ST was reduced by the higher expression of Mdmx and by MDMX and by the reduction of phosphorylation of p53 at Ser(392). |

Cell death induced by hypoxia in ST follows a non-p53-dependent pathway. Down-regulation in response to hypoxia, p53 in ST may reduce apoptosis, thereby limiting cell death and maintaining its integrity. |

|

| Staurosporine and nutlin-3 both raised p53 levels and increased apoptosis. p53 was localized to both cytoplasm and nuclei of nutlin-3-exposed ST. Hypoxia-induced apoptosis in ST correlated with enhanced expression of the pro-apoptotic Bad and a reduced level of anti-apoptotic Bad phosphorylated on Ser(112). |

|||||||

Abbreviations: CT, cytotrophoblast; COX, cyclo-oxygenase; CoCl2, cobalt chloride; DMOG, dimethyloxaloylglycine; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EVT, extravillous trophoblast; FSTL3, follistatin-like 3; hCG, secreted human chorionic gonadotropin; H/R, Hypoxiareoxygenation; HSP, heat shock protein; HIF-1α, hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha; HNE, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal; IL, interleukin; IF, immunofluorescence; IHC, immunohistochemistry; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; LDH, extracellular lactate dehydrogenase; MAC, membrane attack complex; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; Mib-1, mindbomb homolog 1; M30, cleaved cytokeratin 18; Mdm2, murine double minute 2; Mdmx, murine double minute x; NF-kB, nuclear factor-kappa B; nutlin-3, drug that elevates-53 levels, PE, pre-eclampsia; p53, tumor suppressor p53 protein; PHT, primary human trophoblast; PTHrP, parathyroid hormone-related protein; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SAPK, stress-activated protein kinase; ST, syncytiotrophoblast; survivin, member of inhibitor of apoptosis family (IAP); staurosporine, apoptosis inducing kinase inhibitor; TNF-a, tumor necrosis factor alpha; XIAP, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis.

Hypoxia (1% oxygen), hyperoxia (21%, 95% oxygen) and hypoxia-reoxygenation activate pathways and mechanisms involved in trophoblast metabolism and cell death [43].

Hypoxia (1% oxygen) is associated with a shift towards proliferation in first trimester specimens and reduced differentiation of cytotrophoblasts from both first and third trimester placentas [52,55].

Phenotypic changes of villi in response to hypoxia (1% oxygen) and hypoxia-reoxygenation in vitro mimics some of the changes described in placentas from pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia and FGR [53].

Placental cells from pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia and FGR demonstrate exaggerated responses to hypoxia (3% oxygen) in vitro [50].

Hypoxia (1% oxygen) produces metabolic footprints in lysates and conditioned culture medium of villi and trophoblast that offer metabolomic insights into the global placental responses to hypoxia [57].

Oxygen conditions used among investigators are heterogeneous and should be considered when comparing and interpreting experimental results [33,50,52,58,59].

6. Trophoblast responses to hypoxia include apoptosis and autophagy

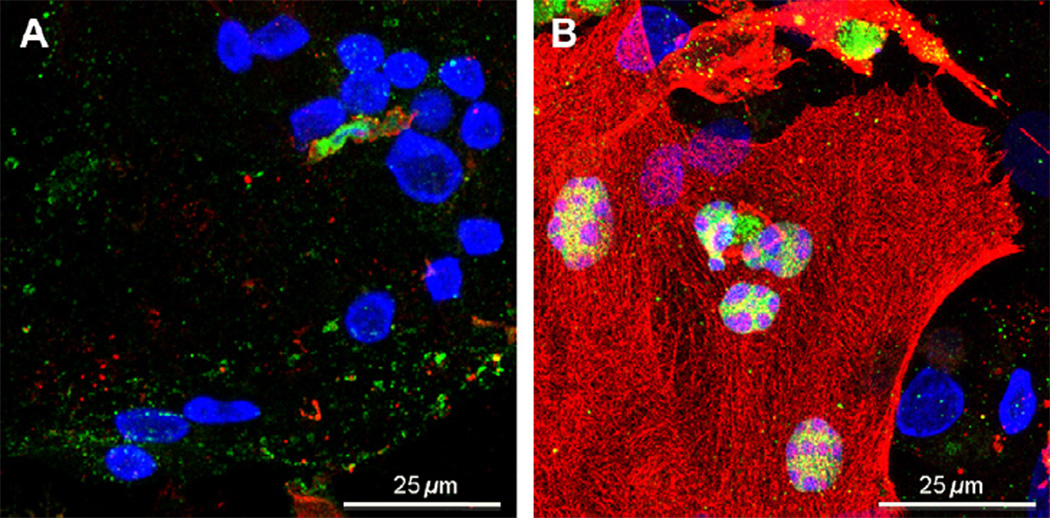

Apoptosis, a regulated method of cell death, is one important response of placental trophoblasts to stress [61–63]. Apoptosis can be triggered by ligand–receptor interactions that activate the extrinsic pathway or by exogenous stress that activates the mitochondrial pathway. TNF-α ligand enhances cell death and is produced in higher-than-normal concentrations in villi exposed to hypoxia. Hypoxia and oxidative stress also activate the intrinsic or mitochondrial apoptotic pathway. The apoptotic pathways are regulated in a complex manner through multiple signaling mechanisms with cross talk among pathways. A key regulator is p53 and enhanced expression of p53 typically accompanies conditions that are pro-apoptotic. Other important regulators are in the Bcl-2 family, a group of >25 proteins that share one or more Bcl-2 homology domains and that include pro- and anti-apoptotic members. Differential expression and post-translational modifications of these proteins induce or prevent apoptosis, depending on the summation of protein-protein interactions [62,64]. Activation of either death pathway yields a common downstream event, enhanced activity of caspase proteases. Activated caspases cleave multiple cellular substrates, including cytoplasmic cytokeratin 18 intermediate filaments, and nuclear proteins such as poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (Fig. 2). The end products of apoptotic cell death are packaged in vesicular apoptotic bodies that are recognized and phagocytized by resident cells or macrophages, with no inflammatory response [65]. This markedly contrasts with necrotic cell death, in which cell lysis occurs and cell contents are released to induce a strong inflammatory response.

Fig. 2.

Hypoxia-induced apoptosis in human trophoblasts. Primary human trophoblasts were cultured in 20% oxygen for 48 h, by which time most cells have fused to form syncytiotrophoblast and then were followed by 24 h exposure to (A) 20% oxygen or (B) <1% oxygen. Cells were stained for DNA (blue) and with antibodies specific for the caspase-specific cleaved forms of poyl (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (green) or cytokeratin 18 (red), which are nuclear and cytoplasmic markers of apoptosis, respectively. Stained cells were imaged by confocal microscopy, obtaining a Z-stack of 12 images, 0.5 mm apart, which were compressed to a maximum pixel value image. Note, that in the image in (B) as expected the Z-stack images indicate the nuclei do not contain cleaved cytokeratin 18; this appearance results from formation of the collapsed image.

Primary human cytotrophoblasts exposed to <1% oxygen, compared to 20% oxygen, show increased internucleosomal cleavage of DNA, increase of pro-apoptotic p53 and Bax, and a decrease of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 [47]. Cytotrophoblasts exposed to hypoxia undergo apoptosis to a greater extent than hypoxic syncytiotrophoblast in culture, with higher caspase 3 activity, increased cleavage of the caspase substrates cytokeratin 18 and PARP, and an increased physical interaction between p53 and the pro-apoptotic protein, Bak [66]. Importantly, in cytotrophoblasts, epidermal growth factor reverses the hypoxia-induced decrease in phosphorylation of Bad at serine 112. Bad phosphorylated at this residue is sequestered by cytoplasmic 14-3-3 proteins so that translocation of Bad to mitochondria does not occur and apoptosis is not induced [67]. Collectively, these results show that the response of term trophoblasts to hypoxia is phenotype dependent and in cytotrophoblasts involves elevated p53 activity, increases in pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins, and decreases in anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins. Although to a lesser extent than in cytotrophoblasts, hypoxia does increase apoptosis in syncytiotrophoblast, the mechanism for this cell death appears different than in hypoxic cytotrophoblasts. Notably, hypoxia induces a surprising decrease in p53 activity in syncytiotrophoblast, perhaps to protect this key villous interface from some of the deleterious effects of a hypoxic insult [60,66].

Cell death in general, and apoptosis in particular, occurs on a continuum of death pathways that range from elimination of misfolded proteins, to disposal of organelles, to elimination of whole cells as described above from apoptosis. Much recent attention in other cell systems has focused on autophagy as a highly regulated process of turnover of cell constituents by the autopha-gosomal-lysosomal system [68] but little is known about this process in human trophoblasts. In autophagy, double-membrane vesicles called autophagosomes form de novo and encircle damaged cell constituents, and these components are degraded after lysosomes fuse with the autophagosome. Although autophagy is often referred to as a “cell death pathway”, cell-stress induced autophagy is generally a defense mechanism for removal of damaged components and recycling of degraded substrates for use in cell metabolism [69,70]. This response commonly results in a cytoprotective effect when cells are exposed to nutrient deprivation, ATP depletion, or hypoxia.

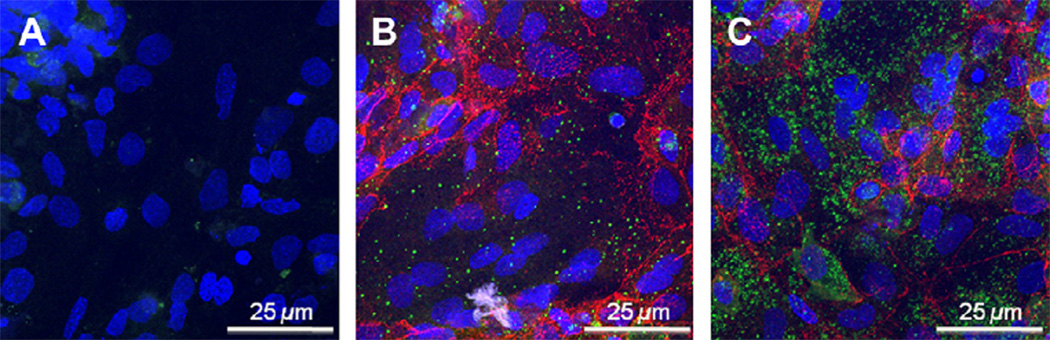

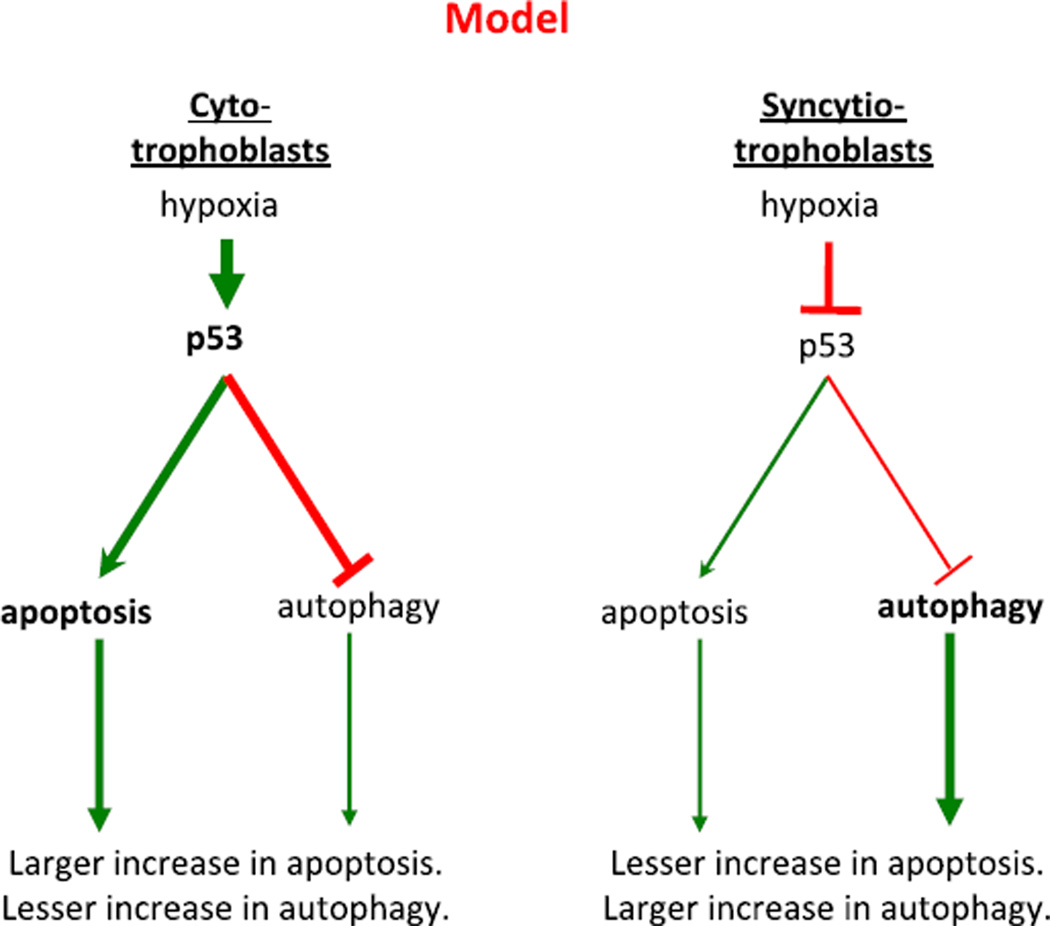

We propose that autophagy and apoptosis in human trophoblasts are interrelated pathways, with increases in one reducing the flux through the other. In unpublished work, we have identified autophagy in human trophoblasts. Treatment of trophoblasts with rapamycin, which inhibits the mTOR kinase and thereby induces autophagy [71], results in increased puncta of p62/SQSTM1 (Fig. 3), a marker for autophagic vesicles. Similarly, exposure to hypoxia results in rapid inactivation of mTOR and increases in the levels of LC3BII, another marker for autophagic vesicles (data not shown). Thus, hypoxia induces not only apoptosis but also autophagy in human trophoblasts. Taken together, we propose the following highly speculative, but testable, model for the interplay of hypoxia, apoptosis and autophagy in trophoblasts (Fig. 4). In cytotrophoblasts, hypoxia results in large increases in both p53 levels and in apoptosis. We speculate that the increased p53 represses the induction of autophagy, as described in other cell types [72,73]. In syncytiotrophoblast, hypoxia results in decreased levels of p53 and a lesser induction of apoptosis. We speculate that the reduced p53 t in syncytiotrophoblast promotes a larger increase in autophagy, compared to cytotrophoblasts, allowing survival of the syncytium and maintaining the interface between the maternal and fetal circulations. All aspects of this model are testable, and are currently under investigation in our laboratory.

Fig. 3.

mTOR responsive autophagy in human trophoblasts. Primary human trophoblasts were cultured in 20% oxygen for 68 h, to form multiple syncytiotrophoblasts and these were exposed to 4 h of (A) DMSO vehicle control, (B) 250 nM rapamycin to inhibit mTOR or, (C) 250 nM rapamycin and 200 nM bafilomycin, the latter of which prevents fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes to inhibit degradation of p62. Cells were stained for DNA (blue) and with (a) no primary antibodies, or (b) primary antibodies to p62/SQSTM1 (green) or (c) to desmoplakin (red), to delineate regions of cell-cell contact as determined by confocal microscopy. The absence of desmoplakin indicates the presence of syncytiotrophoblasts.

Fig. 4.

Proposed model for the effects of hypoxia on apoptosis and autophagy in trophoblasts. In cytotrophoblasts (left), hypoxia results in marked increases in p53 activity and yields apoptosis. The increased p53 represses the induction of autophagy. In syncytiotrophoblasts (right), hypoxia results in diminished levels of p53 and a lesser induction of apoptosis. The reduced p53 promotes autophagy to promote the survival of the syncytiotrophoblast, which is a key interface between maternal and fetal circulations.

7. Controversies

7.1. What oxygen tension is physiologic and what is pathologic?

Based on the above discussions, we propose a goal of 40–80 mm Hg for in vitro oxygen tensions to mimic physiological conditions in studies of term villi. Support for this recommendation derives from measurement of oxygen tensions and assessment of gene expression profile in different locations of the placenta [74,75]. The pO2 varies from as high as 80 mmHg in the center of a placental lobule to as low as 40 mm Hg in the periphery of the placenta. We realize that the oxygen concentrations considered to be physiological in the intervillous space of term pregnancy are based on a limited number of studies with small sample sizes and wide ranges. Moreover, the pattern of maternal blood flow and the regional variations that exist among placental villi in situ create oxygen gradients with variable oxygen concentrations. The choice of this range is therefore pragmatic but qualified. As the oxygen tension differs depending on the site of sampling from the placenta, care must also be taken to be consistent in sampling techniques to also reduce experimental variability. In addition, since during most of the first trimester there is no blood flow to the developing placenta but rather plasma flow, in vitro studies using first trimester placenta samples may be much closer to the in vivo situation compared to term trophoblast studies. More studies using first trimester placenta samples are needed.

7.2. What are the actual oxygen concentrations at the medium-cell interface?

In the absence of an oxygen carrier, the actual concentration of dissolved oxygen achieved in culture medium and at the surface of cultured cells may differ substantially from the predicted, or target, level. Importantly, experiments that measure pericellular oxygen levels reveal important insights into the actual versus theoretical oxygen concentrations and the time needed for equilibration of the medium with the ambient atmosphere.

Kilani et al. measured pO2 values and found they closely mirrored the predicted concentrations. The theoretical and measured pO2 levels in a humidified culture chamber were 142 mm Hg and 135–145 mmHg in 21% O2, respectively [48]. Similarly, 2% O2 had a 15 mmHg theoretical and a 14–16 mmHg actual pO2. Huppertz et al. also showed the partial pressure of oxygen in the culture media exposed to 2% oxygen was 17.4 ± 2.3 mm Hg (2.3%), to 6% was 39.8 ± 1.0 mm Hg (5.2%), and to 18% oxygen was 138.4 ± 4.0 (18.2%) [49]. These studies contrast with one measuring the pO2 in an ambient atmosphere of 95% O2 where the measured pO2 was 561 mmHg, compared to a theoretical value of 722 mmHg [43]. Importantly, the latter study also showed that both the theoretical and measured pO2 for a given percentage of oxygen varies with the type of incubation chamber, humidification and the duration of equilibration.

Investigators performing experiments on the effect of oxygen on trophoblast must ensure that culture medium is equilibrated with the chamber prior to the start of the experimentation. Variables influencing oxygen equilibration include time, pre-gassing, and shaking [55,76]. Newby et al. highlighted some of the problems, as they noted that on transferring culture media from 18% O2 to 2% O2 the measured oxygen levels decreased to 6–8% after 4 h but reached 2% only after 24 h. Pre-gassing culture media with nitrogen to remove dissolved oxygen prior to incubation in 2% O2 resulted in equilibration within 1 h, but exposure of pre-gassed culture medium to ambient air resulted in the quick absorption of oxygen, requiring further incubation in 2% O2 before dissolved oxygen levels again equilibrated [76]. These findings have been corroborated by others [55] and underscore the need to allow adequate time for equilibration with ambient gas prior to culture.

The final step in the chain of oxygen transfer from the culture chamber to cells suggests that oxygen consumption by cells can result in pericellular oxygen levels that are markedly different from the expected oxygen concentrations. For example, measurements in a variety of cell lines indicate that the majority of cells exposed to 20% oxygen actually experience a pO2 that is far below the predicted 160 mmHg, ranging instead from 88 to 120 mmHg when actually measured [46]. Notably, some epithelial cell lines at confluence are in apparent hypoxia (pO2 <1 mmHg) even in 20% oxygen. As one would expect, densely plated primary cultures, as often required for optimal culture of primary trophoblasts, yield a pericellular pO2 in the lower portion of the range [77,78]. Thus, cell culture in 20% oxygen likely replicates a normal physiological cellular oxygen exposure of trophoblasts more than what one might otherwise predict.

Most agree that oxygen paradigms used for experiments involving trophoblast should be validated prior to their use. Some investigators suggest that the dissolved oxygen concentration as well as the oxygen concentration in the gaseous phase should be measured to verify that equilibration has occurred [39]. However, given the difficulty in determining the exact oxygen concentrations that are physiologic and in replicating them in vitro, an alternative and more pragmatic approach is for investigators to explore the effect of a range of oxygen concentrations to achieve a dose–response effect, while bearing in mind no in vitro system completely mimics in vivo physiology or pathology [79]. Repeating experiments multiple times will also help overcome the variability in paradigm oxygenation and the inadvertent introduction of oxidative stress in selected experiments [39].

7.3. Do culture conditions adequately represent the in vivo environment?

Experiments to study the effect of oxygen on trophoblast are , based on the assumption that oxygen concentration is the only independent variable. This is a crucial prerequisite for a valid interpretation of results. However, the question of whether this is true or not is debated, too. First, the oxidative stress generated in different cell types depends not only on the concentration of oxygen to which cells are exposed, but also on their endogenous antioxidant defenses. Explants, trophoblasts, stromal cells, and vascular endothelium may each experience different levels of oxidative stress related to their antioxidant defenses. For this reason, a combination of immunohistochemistry combined with immu-noblotting is preferable in experiments that study oxygen effects on placental tissue, since the two analytical methods are complementary [26]. Second, the placenta in vivo is exposed to maternal blood, which also contains abundant antioxidants that protect against oxidative stress. Such antioxidants are not present in culture media, resulting in a greater sensitivity to oxidative stress. Finally, since trophoblast responses to stress, which includes apopotosis and autophagy, are affected by nutrients, care must be taken to avoid assignment of oxygen as the sole agent for induced phenotypic changes in trophoblast in vitro, when the changes may actually be the result of depletion of one or more key nutrients or changes in medium pH. Frequent replacement of medium can limit these pitfalls.

8. Conclusion

Oxygen is a profound regulator of placental development and function. Pregnancy complications ranging from miscarriage to preeclampsia result when oxygen is dysregulated. The marked effect of oxygen on trophoblast entices all of us as placental biologists to experimentally manipulate oxygen tension. Major hurdles for validity of the results include the absence of an oxygen carrier in culture media, uncertainty of the target oxygen concentrations that are normal for a given gestational age, the difficulty in establishing the pericellular oxygen concentration in culture cells, and the incidental oxidative stress introduced inadvertently during sample collection. Given these difficulties, a pragmatic approach is for investigators to assay the effect of a range of oxygen concentrations in order to identify a dose–response effect, while recognizing that oxygen concentrations from in vivo measurements may not be reflected in the in vitro paradigm. The many controversies notwithstanding, the data show that level of oxygen markedly influences trophoblast in a gestational age and phenotype dependent manner.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Baosheng Chen, PhD, for his contribution to the initial work on p53 and apoptosis. Support: NIH RO1 HD29190.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Jauniaux E, Gulbis B, Burton GJ. The human first trimester gestational sac limits rather than facilitates oxygen transfer to the foetus – a review. Placenta. 2003;24(Suppl. A):S86–S93. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter AM. Placental oxygen consumption. Part I: in vivo studies – a review. Placenta. 2000;21(Suppl. A):S31–S37. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burton GJ, Jauniaux E. Placental oxidative stress: from miscarriage to preeclampsia. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2004;11(6):342–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore KL, Persaud TVN. Clinically oriented embryology. 8th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2007. The developing human. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pijnenborg R, Bland JM, Robertson WB, Dixon G, Brosens I. The pattern of interstitial trophoblastic invasion of the myometrium in early human pregnancy. Placenta. 1981;2(4):303–316. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(81)80027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jauniaux E, Jurkovic D, Campbell S. In vivo investigations of the anatomy and the physiology of early human placental circulations. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1991;1(6):435–445. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1991.01060435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaffe R, Woods JR., Jr. Color Doppler imaging and in vivo assessment of the anatomy and physiology of the early uteroplacental circulation. Fertil Steril. 1993;60(2):293–297. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hustin J, Schaaps JP. Echographic [corrected] and anatomic studies of the maternotrophoblastic border during the first trimester of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157(1):162–168. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80371-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burton GJ, Jauniaux E, Watson AL. Maternal arterial connections to the placental intervillous space during the first trimester of human pregnancy: the Boyd collection revisited. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181(3):718–724. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70518-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burton GJ, Watson AL, Hempstock J, Skepper JN, Jauniaux E. Uterine glands provide histiotrophic nutrition for the human fetus during the first trimester of pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(6):2954–2959. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.6.8563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jauniaux E, Watson A, Ozturk O, Quick D, Burton G. In-vivo measurement of intrauterine gases and acid-base values early in human pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 1999;14(11):2901–2904. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.11.2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodesch F, Simon P, Donner C, Jauniaux E. Oxygen measurements in endometrial and trophoblastic tissues during early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80(2):283–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jauniaux E, Watson AL, Hempstock J, Bao YP, Skepper JN, Burton GJ. Onset of maternal arterial blood flow and placental oxidative stress A possible factor in human early pregnancy failure. Am J Pathol. 2000;157(6):2111–2122. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64849-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charnock-Jones DS, Burton GJ. Placental vascular morphogenesis. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;14(6):953–968. doi: 10.1053/beog.2000.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Espinoza J, Sebire NJ, McAuliffe F, Krampl E, Nicolaides KH. Placental villus morphology in relation to maternal hypoxia at high altitude. Placenta. 2001;22(6):606–608. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayhew TM, Charnock-Jones DS, Kaufmann P. Aspects of human fetoplacental vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. III. Changes in complicated pregnancies. Placenta. 2004;25(2–3):127–139. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jauniaux E, Hempstock J, Greenwold N, Burton GJ. Trophoblastic oxidative stress in relation to temporal and regional differences in maternal placental blood flow in normal and abnormal early pregnancies. Am J Pathol. 2003;162(1):115–125. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63803-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sjostedt S, Rooth G, Caligara F. The oxygen tension in the cord blood after normal delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1960;39:34–38. doi: 10.3109/00016346009157834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaaps JP, Tsatsaris V, Goffin F, Brichant JF, Delbecque K, Tebache M, et al. Shunting the intervillous space: new concepts in human uteroplacental vascularization. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(1):323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rooth G, Sjostedt S, Caligara F. Hydrogen concentration, carbon dioxide tension and acid base balance in blood of human umbilical cord and intervillous space of placenta. Arch Dis Child. 1961;36:278–285. doi: 10.1136/adc.36.187.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soothill PW, Nicolaides KH, Rodeck CH, Campbell S. Effect of gestational age on fetal and intervillous blood gas and acid-base values in human pregnancy. Fetal Ther. 1986;1(4):168–175. doi: 10.1159/000262264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Majmundar AJ, Wong WJ, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40(2):294–309. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang GL, Semenza GL. General involvement of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in transcriptional response to hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(9):4304–4308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carmeliet P, Dor Y, Herbert JM, Fukumura D, Brusselmans K, Dewerchin M, et al. Role of HIF-1alpha in hypoxia-mediated apoptosis, cell proliferation and tumour angiogenesis. Nature. 1998;394(6692):485–490. doi: 10.1038/28867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burton GJ. Oxygen, the Janus gas; its effects on human placental development and function. J Anat. 2009;215(1):27–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00978.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hempstock J, Jauniaux E, Greenwold N, Burton GJ. The contribution of placental oxidative stress to early pregnancy failure. Hum Pathol. 2003;34(12):1265–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zamudio S. The placenta at high altitude. High Alt Med Biol. 2003;4(2):171–191. doi: 10.1089/152702903322022785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zamudio S, Kovalenko O, Vanderlelie J, Illsley NP, Heller D, Belliappa S, et al. Chronic hypoxia in vivo reduces placental oxidative stress. Placenta. 2007;28(8–9):846–853. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tissot van Patot MC, Murray AJ, Beckey V, Cindrova-Davies T, Johns J, Zwerdlinger L, et al. Human placental metabolic adaptation to chronic hypoxia, high altitude: hypoxic preconditioning. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;298(1):R166–R172. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00383.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fleischer A, Anyaegbunam AA, Schulman H, Farmakides G, Randolph G. Uterine and umbilical artery velocimetry during normal labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157(1):40–43. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80342-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diamant S, Kissilevitz R, Diamant Y. Lipid peroxidation system in human placental tissue: general properties and the influence of gestational age. Biol Reprod. 1980;23(4):776–781. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod23.4.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Many A, Roberts JM. Increased xanthine oxidase during labour implications for oxidative stress. Placenta. 1997;18(8):725–726. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(97)90015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cindrova-Davies T, Yung HW, Johns J, Spasic-Boskovic O, Korolchuk S, Jauniaux E, et al. Oxidative stress, gene expression, and protein changes induced in the human placenta during labor. Am J Pathol. 2007;171(4):1168–1179. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myatt L, Cui X. Oxidative stress in the placenta. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;122(4):369–382. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0677-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Many A, Hubel CA, Roberts JM. Hyperuricemia and xanthine oxidase in preeclampsia, revisited. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174(1 Pt 1):288–291. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70410-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee KJ, Shim SH, Kang KM, Kang JH, Park DY, Kim SH, et al. Global gene expression changes induced in the human placenta during labor. Placenta. 2010;31(8):698–704. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soleymanlou N, Jurisica I, Nevo O, letta F, Zhang X, Zamudio S, et al. Molecular evidence of placental hypoxia in preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(7):4299–4308. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burton GJ, Woods AW, Jauniaux E, Kingdom JC. Rheological and physiological consequences of conversion of the maternal spiral arteries for uteroplacental blood flow during human pregnancy. Placenta. 2009;30(6):473–482. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burton GJ, Charnock-Jones DS, Jauniaux E. Working with oxygen and oxidative stress in vitro. Methods Mol Med. 2006;122:413–425. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-989-3:413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zamudio S. Hypoxia and the placenta. In: Helen Kay, Michael Nelson D, Yuping Wang., editors. The placenta from development to disease. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nguyen HT, Rice GE, Farrugia W, Wong M, Brennecke SP. Bacterial endotoxin increases type II phospholipase A2 immunoreactive content and phospholipase A2 enzymatic activity in human choriodecidua. Biol Reprod. 1994;50(3):526–534. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod50.3.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lappas M, Permezel M, Georgiou HM, Rice GE. Regulation of phospholipase isozymes by nuclear factor-kappaB in human gestational tissues in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(5):2365–2372. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reti NG, Lappas M, Huppertz B, Riley C, Wlodek ME, Henschke P, et al. Effect of high oxygen on placental function in short-term explant cultures. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;328(3):607–616. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0375-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Csete M. Oxygen in the cultivation of stem cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1049:1–8. doi: 10.1196/annals.1334.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guerin P, El Mouatassim S, Menezo Y. Oxidative stress and protection against reactive oxygen species in the pre-implantation embryo and its surroundings. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7(2):175–189. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Metzen E, Wolff M, Fandrey J, Jelkmann W. Pericellular PO2 and O2 consumption in monolayer cell cultures. Respir Physiol. 1995;100(2):101–106. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(94)00125-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Levy R, Smith SD, Chandler K, Sadovsky Y, Nelson DM. Apoptosis in human cultured trophoblasts is enhanced by hypoxia and diminished by epidermal growth factor. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;278(5):C982–C988. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.5.C982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kilani RT, Mackova M, Davidge ST, Guilbert LJ. Effect of oxygen levels in villous trophoblast apoptosis. Placenta. 2003;24(8–9):826–834. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(03)00129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huppertz B, Kingdom J, Caniggia I, Desoye G, Black S, Korr H, et al. Hypoxia favours necrotic versus apoptotic shedding of placental syncytiotrophoblast into the maternal circulation. Placenta. 2003;24(2–3):181–190. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crocker IP, Tansinda DM, Baker PN. Altered cell kinetics in cultured placental villous explants in pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. J Pathol. 2004;204(1):11–18. doi: 10.1002/path.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crocker IP, Tansinda DM, Jones CJ, Baker PN. The influence of oxygen and tumor necrosis factor-alpha on the cellular kinetics of term placental villous explants in culture. J Histochem Cytochem. 2004;52(6):749–757. doi: 10.1369/jhc.3A6176.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.James JL, Stone PR, Chamley LW. The effects of oxygen concentration and gestational age on extravillous trophoblast outgrowth in a human first trimester villous explant model. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(10):2699–2705. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heazell AE, Moll SJ, Jones CJ, Baker PN, Crocker IP. Formation of syncytial knots is increased by hyperoxia, hypoxia and reactive oxygen species. Placenta. 2007;28(Suppl. A):S33–S40. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cindrova-Davies T, Spasic-Boskovic O, Jauniaux E, Charnock-Jones DS, Burton GJ. Nuclear factor-kappa B, p38, and stress-activated protein kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways regulate proinflammatory cytokines and apoptosis in human placental explants in response to oxidative stress: effects of antioxidant vitamins. Am J Pathol. 2007;170(5):1511–1520. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seeho SK, Park JH, Rowe J, Morris JM, Gallery ED. Villous explant culture using early gestation tissue from ongoing pregnancies with known normal outcomes: the effect of oxygen on trophoblast outgrowth and migration. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(5):1170–1179. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Biron-Shental T, Schaiff WT, Rimon E, Shim TL, Nelson DM, Sadovsky Y. Hypoxia enhances the expression of follistatin-like 3 in term human trophoblasts. Placenta. 2008;29(1):51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heazell AE, Brown M, Dunn WB, Worton SA, Crocker IP, Baker PN, et al. Analysis of the metabolic footprint and tissue metabolome of placental villous explants cultured at different oxygen tensions reveals novel redox biomarkers. Placenta. 2008;29(8):691–698. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rampersad R, Barton A, Sadovsky Y, Nelson DM. The C5b-9 membrane attack complex of complement activation localizes to villous trophoblast injury in vivo and modulates human trophoblast function in vitro. Placenta. 2008;29(10):855–861. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blankley RT, Robinson NJ, Aplin JD, Crocker IP, Gaskell SJ, Whetton AD, et al. A gel-free quantitative proteomics analysis of factors released from hypoxic-conditioned placentae. Reprod Sci. 2009;17(3):247–257. doi: 10.1177/1933719109351320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen B, Longtine MS, Sadovsky Y, Nelson DM. Hypoxia downregulates p53 but induces apoptosis and enhances expression of BAD in cultures of human syncytiotrophoblasts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299(5):C968–C976. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00154.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.He B, Lu N, Zhou Z. Cellular and nuclear degradation during apoptosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21(6):900–912. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35(4):495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Levy R, Nelson DM. To be or not to be, that is the question Apoptosis in human trophoblast. Placenta. 2000;21(1):1–13. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Danial NN. BAD: undertaker by night, candyman by day. Oncogene. 2008;27(Suppl. 1):S53–S70. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Erwig LP, Henson PM. Clearance of apoptotic cells by phagocytes. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(2):243–250. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hu C, Smith SD, Pang L, Sadovsky Y, Nelson DM. Enhanced basal apoptosis in cultured term human cytotrophoblasts is associated with a higher expression and physical interaction of p53 and Bak. Placenta. 2006;27(9–10):978–983. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Humphrey RG, Sonnenberg-Hirche C, Smith SD, Hu C, Barton A, Sadovsky Y, et al. Epidermal growth factor abrogates hypoxia-induced apoptosis in cultured human trophoblasts through phosphorylation of BAD Serine 112. Endocrinology. 2008;149(5):2131–2137. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang RC, Levine B. Autophagy in cellular growth control. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(7):1417–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gustafsson AB, Gottlieb RA. Recycle or die: the role of autophagy in car-dioprotection. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44(4):654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moreau K, Luo S, Rubinsztein DC. Cytoprotective roles for autophagy. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22(2):206–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jung CH, Ro SH, Cao J, Otto NM, Kim DH. mTOR regulation of autophagy. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(7):1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Green DR, Kroemer G. Cytoplasmic functions of the tumour suppressor p53. Nature. 2009;458(7242):1127–1130. doi: 10.1038/nature07986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Maiuri MC, Galluzzi L, Morselli E, Kepp O, Malik SA, Kroemer G. Autophagy regulation by p53. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22(2):181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hempstock J, Bao YP, Bar-Issac M, Segaren N, Watson AL, Charnock-Jones DS, et al. Intralobular differences in antioxidant enzyme expression and activity reflect the pattern of maternal arterial bloodflow within the human placenta. Placenta. 2003;24(5):517–523. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wyatt SM, Kraus FT, Roh CR, Elchalal U, Nelson DM, Sadovsky Y. The correlation between sampling site and gene expression in the term human placenta. Placenta. 2005;26(5):372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Newby D, Marks L, Lyall F. Dissolved oxygen concentration in culture medium: assumptions and pitfalls. Placenta. 2005;26(4):353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Camins BC, Richmond AM, Dyer KL, Zimmerman HN, Coyne DW, Rothstein M, et al. A crossover intervention trial evaluating the efficacy of a chlorhexidine-impregnated sponge in reducing catheter-related bloodstream infections among patients undergoing hemodialysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(11):1118–1123. doi: 10.1086/657075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thomas PC, Halter M, Tona A, Raghavan SR, Plant AL, Forry SP. A noninvasive thin film sensor for monitoring oxygen tension during in vitro cell culture. Anal Chem. 2009;81(22):9239–9246. doi: 10.1021/ac9013379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Burton GJ, Caniggia I. Hypoxia: implications for implantation to delivery-a workshop report. Placenta. 2001;22(Suppl. A):S63–S65. doi: 10.1053/plac.2001.0642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]