Abstract

Introduction

Juvenile Polyposis (JP) is characterized by the development of hamartomatous polyps along the entire GI tract that collectively carry a significant risk of malignant transformation. Mutations in the Bone Morphogenetic Protein Receptor Type IA (BMPR1A) are known to predispose to JP. We set out to study the effect of such missense mutations on BMPR1A cellular localization.

Methods

Eight distinct mutations were chosen for analysis. A BMPR1A wild type (WT) expression plasmid was tagged with green fluorescent protein (GFP) on its C-terminus. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to recreate JP patient mutations from the WT-GFP BMPR1A plasmid. Mutant expression vector sequences were verified by direct sequencing. BMPR1A expression vectors were transfected into HEK-293T cells, then confocal microscopy performed to determine cellular localization. Four independent observers used a scoring system from 1-3 to categorize the degree of membrane vs. cellular localization.

Results

Of the eight selected mutations, one was within the signaling peptide, 4 were within the extracellular domain, and 3 were within the intracellular domain. The WT BMPR1A vector had strong membrane staining, while all 8 mutations had much less membrane and much more intracellular localization. ELISA assays for BMPR1A demonstrated no significant differences in protein quantities between constructs except for one affecting the start codon.

Conclusion

BMPR1A missense mutations occurring in patients with JP affect cellular localization in an in vitro model. These findings suggest a mechanism by which such mutations can lead to disease by altering downstream signaling through the bone morphogenetic protein pathway.

1. Introduction

Juvenile Polyposis (JP) is a rare syndrome affecting between 1 person per 16,000 to 1 per 100,000 (1). The disease is characterized by the predisposition to hamartomatous polyps generally found in the colorectum, but which may also involve the upper gastrointestinal tract, predominantly the stomach. It is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, and those with JP have a 39% chance of developing colorectal cancer over their lifetime (2).

Germline mutations in two genes are known to cause JP. SMAD4 (3), the common intracellular mediator of the TGF-β pathway, and the bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1A (BMPR1A) (4). Approximately 20-25% of JP cases are due to mutations or deletions of BMPR1A, and 20-25% to SMAD4 (5). The genetic origin of the other half of JP cases is currently unknown.

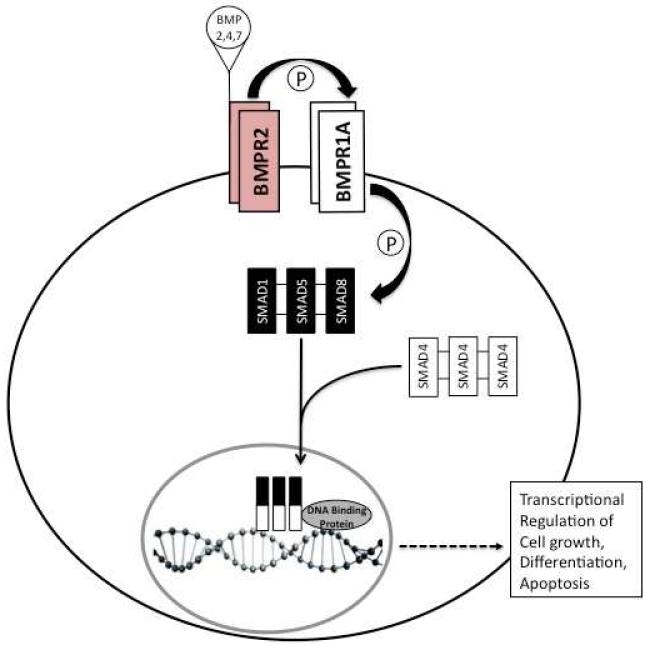

The bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway influences many cell processes, including cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis (6). The BMP type 1 receptor (BMPR1A) is a transmembrane cell-surface receptor that forms a complex with the type 2 receptor (BMPR2) that binds to BMP ligands (BMP2, 4, and 7). After this occurs, BMPR1A phosphorylates receptor-regulated SMADs (R-SMADs, of which SMAD1, 5, and 8 are specific for the BMP pathway), then these bind to SMAD4, and this complex enters the nucleus. The R-SMAD/SMAD4 complex then binds to DNA and regulates transcription, in conjunction with other nuclear DNA binding proteins (Figure 1). It is intuitive that nonsense mutations will have significant effects on protein function, by virtue of truncation and loss of important domains, as well as increased degradation. However, the effect of missense mutations are not always as obvious. The substitution of one amino acid for another may cause changes in a protein’s three-dimensional conformation which may impact its interactions with other proteins, but these alterations can also be of minimal functional significance. The objective of this study was to examine the effects of different BMPR1A missense mutations found in JP patients on the cellular localization of this protein.

Figure 1.

Overview of BMP-signaling pathway. BMPR2 dimers at the cell membrane bind BMP 2,4, or 7, facilitated by their binding to dimers of BMPR1A. Upon ligand binding, BMPR2 phosphorylates BMPR1A, which then phosphorylates intracellular SMAD1, 5, and/or 8. Oligomers of SMAD1,5,or 8 then associate with oligomers of SMAD4, migrate into the nucleus, and associate with DNA binding proteins. This complex binds directly to DNA to regulate transcription of genes involved in cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of BMPR1A mutations

JP patient blood samples were collected under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Iowa. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood by salting out (7) or using the Puregene DNA purification kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and from LCLs by the Qiagen AllPrep DNA mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). DNA was amplified by PCR using primers that flanked all 11 coding exons of BMPR1A. PCR products were purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). PCR products were sequenced by dideoxy cycle sequencing followed by electrophoresis through an ABI model 3730 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Sequences were screened in Sequencher (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), and coding or splice site mutations BMPR1A identified. Eight distinct missense mutants were selected for use in transfection experiments.

2.2 Site directed mutagenesis

A green fluorescent protein (GFP) tagged wild-type BMPR1A expression vector was obtained in a pCMV6-AC-GFP construct (Origene, Rockville, MD, USA). A PCR-based, site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) approach was used to generate individual mutations. Primers containing specific patient mutations were designed using the QC Primer Design Software (Stratagene-Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). PfuUltra (Stratagene-Agilent) was then used to amplify mutant constructs by PCR under the following conditions: 95°C for 30 sec, 65°C for 1 min, and then 7 min at 68°C for 18 cycles. Resulting plasmids were then used to transform XL1-Blue competent bacterial cells, and colonies were selected and DNA extracted using the PureLink Plasmid Quick Miniprep Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). All plasmids were then sequenced to verify the presence of the desired mutations.

2.3. Transfection of cells

Human embryonic kidney cells containing the SV40 large T-antigen (HEK-293T) were used for transfection experiments because of their ease and reliability. These were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). Groups of cells were plated onto glass cover slips in different wells of multiple 6-well plates. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Life Technologies) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin G-streptomycin sulfate (PS) to ~50-80% confluence before transfection. Transfection was optimized by testing under 6 different conditions to maximize expression of GFP-tagged BMPR1A (Table 1). One to two micrograms of each pCMV6-AC-GFP construct were transfected in a 1:3 ratio with Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) into these cells. The cells were then starved by the addition of DMEM without FBS for four hours after transfection. At the end of the four hours, the cells were resuspended in DMEM/FBS, and 25 ug BMP4 ligand was added, in order to stimulate expression.

Table 1.

Different Conditions Used for Transfection

| Trial Number | Time until viewing (hrs.) |

% Confluence | BMP4 Added | Amount of DNA (ug) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 48 | 80 | Yes | 1 |

| 2 | 48 | 80 | Yes | 2 |

| 3 | 48 | 80 | No | 2 |

| 4 | 48 | 50 | Yes | 2 |

| 5 | 24 | 80 | Yes | 2 |

| 6 | 24 | 80 | No | 2 |

2.4. Confocal Microscopy and scoring

After incubation for 24-48 hours prior to confocal microscopy, the media was removed and cells were fixed in 10% formalin. The cover slips were removed from the 6-well plates, and placed on microscope slides. A DAPI stain (Life Technologies) was applied to the cells and incubated at room temperature for ten minutes to make the nuclei visible under confocal microscopy. Specimens were then viewed under 20X and 63X magnification on a BioRad Radiance 2100 confocal microscope (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The images were captured, and contrast-adjusted with ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/). Images were reviewed by four independent observers, blinded to construct identity. After assessing all cells, each image was given a score ranging from one to three, with three indicating predominantly intracellular localization of GFP-tagged BMPR1A, two showing both intracellular and membrane staining, and one with predominant staining of the cell membrane. The mean scores for each image were then calculated.

2.5. Protein extraction and ELISA

HEK293T cells were grown to confluence in 6 well plates, transfected as above with the indicated constructs, and for ELISA experiments the cells were co-transfected with a β-galactosidase plasmid to allow for correction of transfection efficiency. After 24-48 hours, cells were lysed with 2X RIPA buffer with complete mini protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany). Samples were then vortexed, sonicated, and quantified using the Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and Infinite M200 microplate-reader (Tecan, Durham, NC). Fifteen ug of protein was diluted in 6M sodium iodide to a volume of 50 ul, which this amount was distributed into each well of 96-well plates and incubated at 4°C overnight. Each well was washed twice with 200ul/well washing buffer [1×PBST (0.05% Tween20)] and then each well was incubated with 1% BSA in PBS at room temperature for 2 hours in order to block non-specific binding. Fifty ul of BMPR1A primary monoclonal antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; cat# MAB2406) diluted in a 1:500 ratio with 1% BSA in PBS was added to each well of BMPR1A plates, and 50 ul of β-galactosidase antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology cat#sc-40) to duplicate plates. Plates were left at room temperature for 2 hours, was washed twice more with the above buffer, then 50 ul of HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; cat# C2011; diluted in a 1:250 ratio with 1% BSA in PBS) added to each well in the plate, and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. The plate was washed three times with washing buffer, then 50 ul of 3, 3′, 5, 5′-tetramethylbensidine (TMB; Invitrogen-Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) was then added to each well and the plate was incubated in the dark for 10 minutes. Fifty ul of 2M H2SO4 was finally added to stop coloration, and relative protein levels measured using the microplate reader set at 450 nm. Optical density values obtained for the different BMPR1A constructs were then normalized using the results obtained with β-galactosidase for each experiment relative to those obtained from the wild-type vector, then expressed as a percentage of BMPR1A relative to the wild-type vector.

2.6. BRE-Luc experiments

HEK-293T cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% PS. After growth to 90% confluence, the cells were co-transfected with 1 ug of the BRE-Luc vector (a plasmid reporter vector with a BMP responsive element promoter cloned upstream from a luciferase gene)(8), 1 ug of a BMPR1A expression vector (wild-type or mutants), and 200 ng of Renilla (internal control vector for transfection efficiency), using 6 ul Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Each transfection was performed in triplicate. After 4 hours, fresh media was added. 48 hours post-transfection, 500 uL of lysis buffer was added to the cells, which were incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes. Twenty ul of lysate was transferred to a reading tube that contained 100 ul of the Luciferase Assay Reagent II (Promega, Madison, WI) solution, and luciferase activity was measured at 562 nm for 10 seconds using a TD 20/20 luminometer (Turner BioSystems, Sunnyvale, CA). Once initial readings were performed, 100 ul of Stop and Glo reagent (Promega) was added, and Renilla luciferase activity measured at 480 nm for 10 seconds. The final amount of luciferase activity for each construct was determined by subtracting the background luciferase activity of the control pGL3 basic vector without construct, and then normalizing to Renilla luciferase activity for each individual reaction. A Student’s t-test was then performed to assess the statistical significance of differences between triplicate results obtained for each mutant construct relative to the wild-type.

2.7 In silico Evaluation of Mutations

Each BMPR1A missense mutation used was assessed for deleterious effect using the web-based ANNOVAR pipeline (9). This included the algorithms SIFT (10), LRT (11), Blosum62 (12), Polyphen2 (13), MutationTaster (14), GERP++ (15), and PhyloP (16).

3. Results

3.1 Determination of optimal transfection conditions

In order to determine optimal conditions for transfection and subsequent viewing by confocal microscopy, four distinct variables (time, confluence, DNA concentration, and presence of BMP4) were altered in 12 separate colonies of cells; 6 were wild-type, and the other 6 were mutant. Both the mutant and wild-type colonies were exposed to the same six conditions. Of these experimental conditions, transfection of 2 ug at 50% confluence, followed by incubation for 48 hrs. in the presence of BMP4 resulted in the highest expression of GFP and clearest pictures with confocal microscopy. These conditions were used for all subsequent transfections.

3.2 Results of ELISA and Bre-Luc assays

The total level of BMPR1A protein by ELISA was very similar between all of the constructs and the wild-type levels, with the exception of 1A>C (M1L) (Table 2). The latter mutation affects the initiation codon for translation, possibly leading to loss of antibody binding. For the other mutations, the greatest changes in BMPR1A were only 32.4 and 26.9 percent more or less than the wild type, respectively. The mean of these 7 mutant protein levels was 101.6% of wild-type levels (range 73-132%, s.d. 18.5). This suggests that the lack of membrane staining with all but one of the mutant constructs was not likely due to reduced levels of protein.

Table 2.

Results of Scoring by blinded observers and amount of protein detected by ELISA and BMP signaling relative to wild type.

| Genotype | Localization Score | ELISA (% of WT) | BMP Signaling (% of WT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 1 | 100.6 | 100 |

| 1 A>C | 2.25 | 0.0 | 102.8 |

| 170C>G | 2 | 96.6 | 123.1* |

| 184 T>G | 2.75 | 88.8 | 72.8* |

| 233 C>T | 3 | 132.4 | 44.6* |

| 245 G>A | 2 | 120.9 | 36.8* |

| 761 G>A | 2.25 | 106.0 | 146.0 |

| 1013C>A | 3 | 73.1 | 4.6* |

| 1327C>T | 2.75 | 93.6 | 88.2 |

significantly different from Wild-type (WT)

To understand the function of these mutant proteins, changes in BMP signaling were evaluated, as measured by the BMP-specific reported Bre-Luc. These were found to be much more variable, with the mean of all mutant samples 77.4% that of wild type, with a standard deviation of 44.8 percent. Five of eight constructs had reduced BMP signaling activity, ranging as low as 4.6% for the 1013C>A mutation to 72.8% for the 184T>G change (Table 2). The 170C>G and 761G>A were higher than wild-type (123 and 146%, respectively), and interestingly, the 1A>C alteration was essentially the same as wild-type, even though the protein level was absent by ELISA. There was no clear correlation between the localization score and BMP signaling, although both mutations scoring a mean of 3 had low signaling. Conversely, of the two mutations with a mean score of 2, one had reduced signaling whereas the other was increased. These results suggest that different specific mutations exert varied effects on BMPR1A signaling activity, as measured by this surrogate plasmid vector.

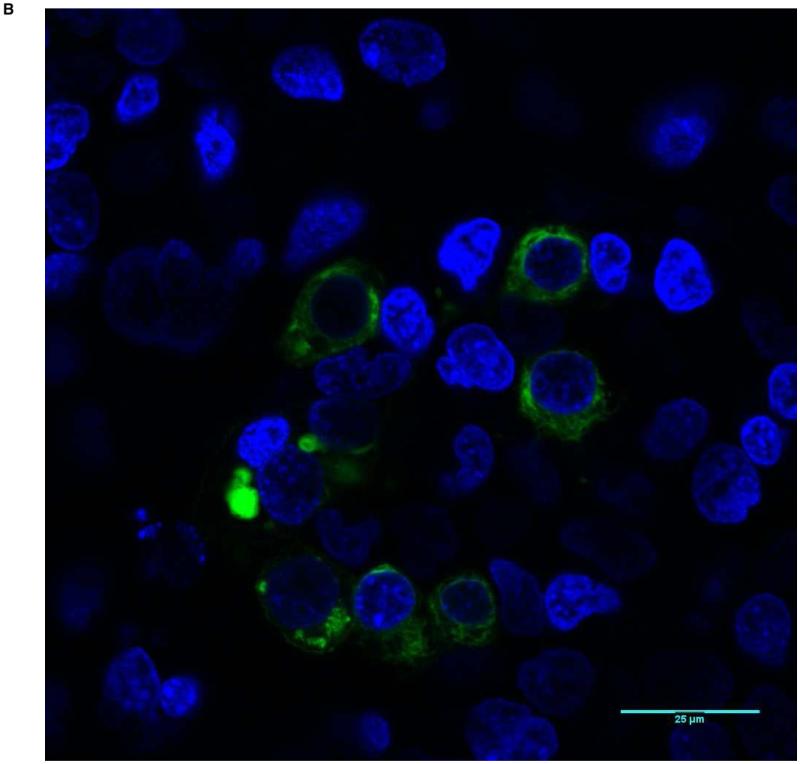

3.3. Patterns of membrane staining

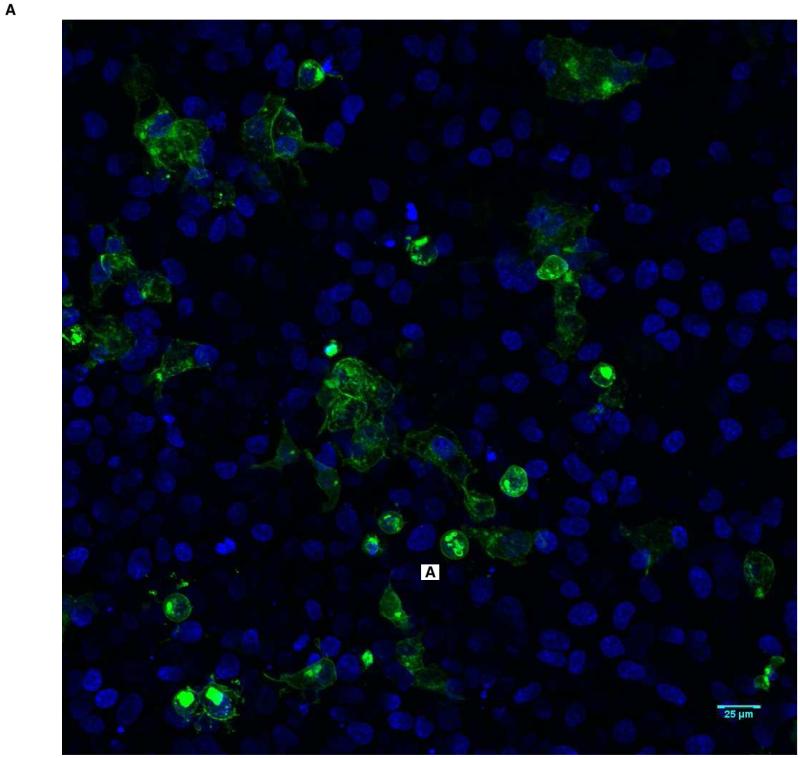

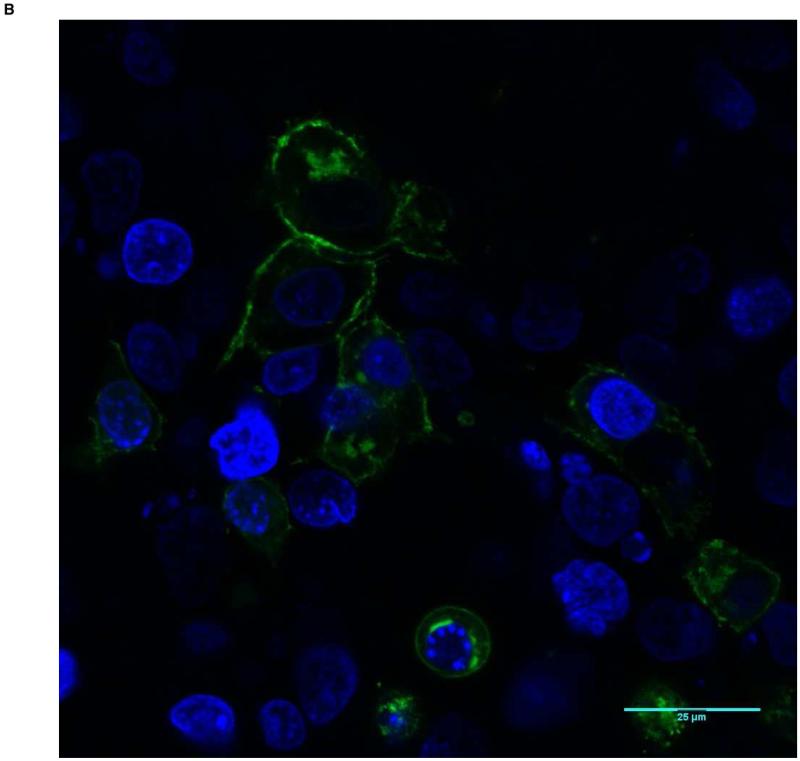

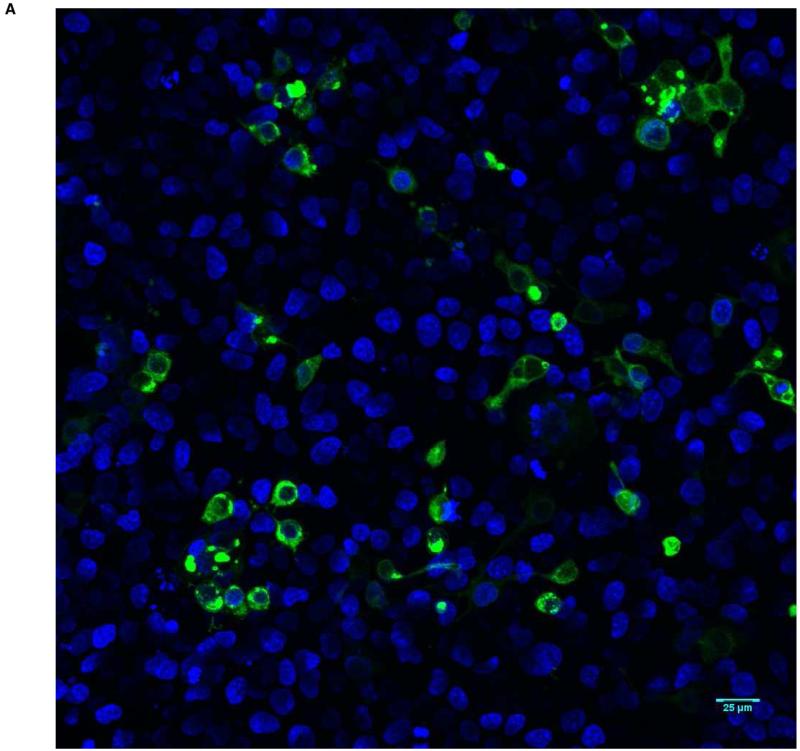

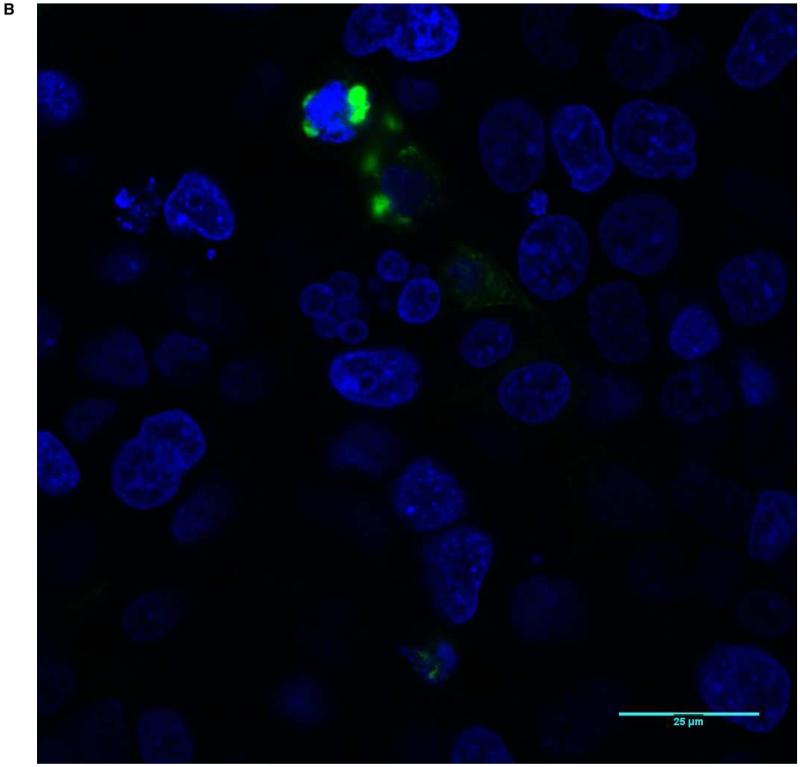

With evidence that mutant proteins are expressed, but have different signaling activity, we next investigated whether abnormal localization of mutant transcripts occurs. All 8 missense constructs as well as wild-type protein were tagged with the sequence for GFP and transfected into HEK-293T cells. Confocal microscopy revealed the location of the expressed protein. In general, approximately 20% of cells had visible expression of GFP-tagged BMPR1A. The wild-type construct showed strong staining at the membrane with only minimal intracellular protein (Figure 2). None of the mutant constructs showed this degree of cell membrane staining with GFP. Some, such as 245 G>A (Figure 3) and 170 C>G, had faint membrane staining, but markedly more intracellular fluorescence than wild-type cells. Others, such as 1013 C>A (Figure 4), and 233 C>T showed near-complete intracellular localization. With high-power microscopy, these mutant proteins were observed around the nucleus, with little or no visible membrane fluorescence.

Figure 2.

Predominant membrane staining pattern (Score of 1) in HEK-293T cells transfected with wild-type BMPR1A. The nuclei are blue, and BMPR1A protein appears as green. A shows a low power view (20X magnification), and B a high power view (63X).

Figure 3.

Score of 2 (Mutation 245 G>A): The majority of GFP-tagged BMPR1A is intracellular with a minority localizing to the cell membrane. A shows a low power view (20X magnification), and B a high power view (63X).

Figure 4.

Score of 3 (Mutation 1013 C>A): Almost all GFP-tagged BMPR1A localizes intracellularly and close to the nucleus, with almost no GFP staining visible along the cell membranes. A shows a low power view (20X magnification), and B a high power view (63X).

To quantify protein localization, confocal images were scored by fourobservers from 1 to 3, with 1 indicating localization at the membrane and 3 indicating localization solely within the cell. All observers unanimously scored the wild-type protein as 1, while all missense constructs were scored as intracellular, ranging between 2 and 3 (Table 2). Taken together, these results show that while wild-type BMPR1A is observed almost exclusively at the membrane of BMP-stimulated cells, JP-associated mutant BMPR1A receptors show varying degrees of mislocalization to the intracellular compartment. Furthermore, the 1013 C>A and 233 C>T mutations, which showed the lowest levels of membrane-localized protein also demonstrated the lowest BMP pathway signaling by Bre-luc reporter, suggesting that mislocalization can be associated with impaired protein function.

3.4 In silico Mutation Analysis

To investigate the relationship between our observations and in silico predictions of altered protein function, all mutations were analyzed with several pathogenicity prediction tools for missense mutations (Table 3). As expected for known disease variants, all were predicted to be deleterious by at least 5 of 7 tools. The 184 T>G, 245 G>A, and 1327 C>T mutations were scored as deleterious by all seven tools, and only two mutations, 1 A>C by BLOSUM and PolyPhen2 and 170 C>G by PolyPhen2, were predicted to be tolerated by any algorithm. Strong predictions of pathogenicity were assigned to all mutations by GERP++, Mutation Taster, LRT, and PhyloP, reflecting high conservation of the affected residues among homologous proteins. Variations between different mutations’ pathogenicity scores did not correlate with observed differences in receptor localization or BMP signaling.

Table 3.

Results of in silico predictions of mutation effect on protein function

| Nucleotide Change; Amino Acid Change |

PhyloP | BLOSUM 62 |

SIFT | Poly Phen2 |

LRT | Mutation Taster |

GERP++ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 A>C; M1L | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5.14 |

| 170 C>G; P57R | 1.00 | −2.00 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 5.66 |

| 184 T>G; Y62D | 1.00 | −3.00 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.50 |

| 233 C>T; T78I | 1.00 | −1.00 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5.48 |

| 245 G>A; C82Y | 1.00 | −2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5.48 |

| 761G>A; R254H | 1.00 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5.49 |

| 1013 C>A; A338D | 1.00 | −2.00 | 0.93 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4.81 |

| 1327 C>T; R443C | 1.00 | −3.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ^ 1.00 | 5.58 |

PhyloP, SIFT, PolyPhen2, LRT, and Mutation Taster: Range 0 to 1 with >0.95 deleterious, <0.05 likely benign

BLOSUM62: Range −3 to +3 with <0 likely deleterious

GERP++: Values >0 indicate likely constrained residue

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that BMPR1A missense mutations, as found in the germline of JP patients, did not result in decreased protein levels in vitro (except one affecting the initiation codon), and 5 of 8 lead to reduced BMP signaling, as measured by a BMP-specific reporter vector. More strikingly, all of the GFP-tagged proteins resulting from these mutant expression vector constructs showed reduced localization to the cell membrane, with accumulation in the cytoplasm. This shows a direct, functional consequence of these mutations, and one explanation for impairment of the BMP pathway in these patients. Determining the specific mechanisms by which these point mutations lead to impaired trafficking to the cell membrane will require further study, but several insights become evident from previous studies.

Beginning with different predictive algorithms for missense mutations, all appeared to be potentially damaging using the majority of these programs (Table 3). The two exceptions were the mutation in the signal peptide (1A>C; M1L), and in the extracellular domain (170C>G; P57R). The N-terminal region of BMPR1A contains a signal peptide (amino acids 1-23), which presumably helps direct localization and transport of the protein. Therefore, it is not surprising that 1A>C (M1L) mutation might lead to reduced membrane-bound receptor. The results for this mutation in this study were conflicting: no protein was found by ELISA, while BMP-signaling was comparable to wild-type, and GFP expression was readily observed and predominantly cytoplasmic. A missense mutation affecting the initiation codon would be expected to be faithfully copied into mRNA, then at the 40S ribosomal level it would not be recognized. Scanning in a 3′ direction would continue until another AUG was found in the appropriate context to begin translation into protein. The next AUG triplet in the BMPR1A mRNA occurs in exon 2, at position 85 of the wild-type sequence, which also has a purine 3 bases upstream, which increases the chance of recognition of this start site (17). If translation began here, it would remain in-frame but result in loss of the first 28 amino acids, while preserving the remainder of the protein. Details on the specific epitope recognized by the BMPR1A monoclonal antibody used in this study are lacking, but it was raised using an immunogen consisting of amino acids 1-152 (R&D Systems, personal communication). Our results suggest that the antibody likely binds within these first 28 amino acids, and therefore no protein was detected by ELISA. However, its GFP-tag was seen by confocal microscopy, and it could still drive BMP-signaling by virtue of preservation of the majority of the protein.

The extracellular domain of BMPR1A (residues 24-152) is the site of BMP-ligand binding, and the 3 other extracellular domain mutations (Y62D, T78I, and C82Y) were all predicted to be deleterious using each algorithm. These occurred in the cysteine-rich portion involving residues 61-130, where there are 5 disulfide bonds (between amino acids 61 and 82; 63 and 67; 76 and 100; 110 and 124; and 125-130; www.nextprot.org/db/entry/NX_P36894/sequence). The C82Y mutation directly alters one of these cysteine residues, and it is likely that the others would also interfere with the protein’s normal 3-D configuration, which might be needed for forming other disulfide bonds, important for BMP ligand binding. The Y62D mutation would change a hydrophobic tyrosine to a negatively charged aspartate, and the interaction between BMP-2 with BMPR1A requires a hydrophobic pocket consisting of Y62, P60, and Y99 residues (18). The T78I mutation would change a polar, uncharged threonine to a hydrophobic isoleucine, which might also alter BMP binding if it were to get to the membrane. Kotzsch et al. have also shown that 3 extracellular domain mutations found in JP patients (P34R, Y39D, and T55I) that are not main determinants for binding to BMP ligands, nor within the core hydrophobic regions, also inactivate BMP-2 signaling (19). They found that these mutant proteins lost their folding ability relative to wild-type protein, but they appeared to migrate normally from cytoplasm to the cell membrane, which is in contrast to what was found with extracellular domain mutations here.

A few studies have further examined this phenomenon in BMPR1A’s ligand binding partner, the BMPR2 receptor, using HeLa cells transfected with GFP-tagged mutant expression vectors. Radarakanchana et al. showed that 4 mutants affecting cysteines in the ligand binding domain and two in the kinase domain failed to reach the cell surface and accumulated in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), while those affecting aspartate or arginine did make it to the membrane (20). Sobelewski did similar experiments using the C118W mutant, from the cysteine-rich, ligand binding domain of BMPR2 (21). The mutant BMPR2 was again retained in the ER, while the wild-type protein demonstrated predominantly membrane staining (as seen with BMPR1A in this study). Interestingly, they found that mutant BMPR2 co-localized and was retained with BMP type I receptors in the cytoplasm, while wild-type receptors did the same at the cell membrane. The authors also showed that surface expression of mutant BMPR2 could be restored by treating cells with the chemicals chaperones thapsigargin, glycerol, or 4-PBA, and that the mutant protein restored BMP signaling. They point out that accumulation of mutant proteins within the ER may occur through abnormal processing, changes in degradation, or altered ER stress response, and that this is not uncommon in various disease states.

In this study, there did not appear to be a direct correlation between the domain of the mutation and the degree of abnormal localization of BMPR1A protein. There were no mutations studied which involved the transmembrane domain (amino acids 153-176), and to date, no germline mutations have been reported in this region of the gene in JP patients (although one SNP, I164V, has been reported from the 1000 genomes project, and a M167I mutation has been found in a lung cancer sample).

The remaining mutations we examined were in the intracellular domain (amino acids 177-532), which contains the GS region (serine-glycine repeats where BMPR1A is phosphorylated by type II receptors, residues 204-233), and the kinase domain (where SMAD proteins bind and are phosphorylated, residues 234-525). These mutations included R254H, A338D, and R443C, which were all within the kinase domain and predicted to be deleterious by each algorithm (Table 3). Sobolewski et al. observed that a BMPR2 mutant in the intracellular cysteine kinase domain (C483R) was retained in the cytoplasm, and cell membrane localization could be achieved by treatment with the chemical chaperone 4-PBA (21).

Two groups discovered that the splicing factor 3b subunit 4 (SF3b4), a nuclear protein, interacts with the intracellular domain of BMPR1A by yeast two-hybrid assays (22, 23). Nishanian et al. showed that the GS domain was important for BMPR1A’s interaction with the protein, and that deletion mutants of the kinase domain could mask this association (22). Watanabe et al. found that as SF3b4 expression increased, cell membrane localization of BMPR1A decreased, providing an example of decreased trafficking due to interaction with other intracellular proteins (23).

The results of the current study demonstrate that missense mutations of both the extracellular and intracellular regions of BMPR1A lead to impaired localization of the protein from the cytoplasm to the cell membrane. Previous studies suggest that one potential mechanism is that the mutant proteins are entangled in the ER. Determining the intracellular mediators responsible for these observations is beyond the scope of the current experiments, but further studies should focus upon whether there are molecules that bind to mutant BMPR1A proteins and impede them within the cytoplasm, if mutant BMPR1A proteins do not bind as effectively to chaperones responsible for translocationto the cell membrane, or whether endocytosis is increased for mutant receptors.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH Grant R01CA136884-02, and T32 CA148062-01.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Burt RW, Bishop DT, Lynch HT, Rozen P, Winawer SJ. Risk and Surveillance of individuals with heritable factors for colorectal cancer. Bull. WHO. 1993;68:655–664. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brosens LA, van Hattem A, Hylind LM, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Romans KE, Axilbund J, Cruz-Correa M, Tersmette AC, Offerhaus GJ, Giardiello FM. Risk of colorectal cancer in juvenile polyposis. Gut. 2007;56:965–967. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.116913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howe JR, Roth S, Ringold JC, Summers RW, Jarvinen HJ, Sistonen P, Tomlinson IP, Houlston RS, Bevan S, Mitros FA, Stone EM, Aaltonen LA. Mutations in the SMAD4/DPC4 gene in juvenile polyposis. Science. 1998;280:1086–1088. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5366.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howe JR, Bair JL, Sayed MG, Anderson ME, Mitros FA, Petersen GM, Velculescu VE, Traverso G, Vogelstein B. Germline mutations of the gene encoding bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1A in juvenile polyposis. Nature Genet. 2001;28:184–187. doi: 10.1038/88919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calva-Cerqueira D, Chinnathambi S, Pechman B, Bair J, Larsen-Haidle J, Howe JR. The rate of germline mutations and large deletions of SMAD4 and BMPR1A in juvenile polyposis. Clin Genet. 2009;75:79–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Massague J. TGFβ signaling: Receptors, Transducers, and Mad proteins. Cell. 1996;85:947–950. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korchynskyi O, ten Dijke P. Identification and functional characterization of distinct critically important bone morphogenetic protein-specific response elements in the Id1 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4883–4891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang X, Wang K. wANNOVAR: annotating genetic variants for personal genomes via the web. J Med Genet. 2012;49:433–436. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng PC, Henikoff S. Predicting deleterious amino acid substitutions. Genome Res. 2001;11:863–874. doi: 10.1101/gr.176601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chun S, Fay JC. Identification of deleterious mutations within three human genomes. Genome Res. 2009;19:1553–1561. doi: 10.1101/gr.092619.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henikoff S, Henikoff JG. Amino acid substitution matrices from protein blocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:10915–10919. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nature methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwarz JM, Rodelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nature methods. 2010;7:575–576. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0810-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davydov EV, Goode DL, Sirota M, Cooper GM, Sidow A, Batzoglou S. Identifying a high fraction of the human genome to be under selective constraint using GERP++ PLoS computational biology. 2010;6:e1001025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siepel A, Haussler D. Combining phylogenetic and hidden Markov models in biosequence analysis. Journal of computational biology: a journal of computational molecular cell biology. 2004;11:413–428. doi: 10.1089/1066527041410472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bazykin GA, Kochetov AV. Alternative translation start sites are conserved in eukaryotic genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:567–577. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allendorph GP, Vale WW, Choe S. Structure of the ternary signaling complex of a TGF-beta superfamily member. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7643–7648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602558103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotzsch A, Nickel J, Seher A, Heinecke K, van Geersdaele L, Herrmann T, Sebald W, Mueller TD. Structure analysis of bone morphogenetic protein-2 type I receptor complexes reveals a mechanism of receptor inactivation in juvenile polyposis syndrome. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5876–5887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudarakanchana N, Flanagan JA, Chen H, Upton PD, Machado R, Patel D, Trembath RC, Morrell NW. Functional analysis of bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor mutations underlying primary pulmonary hypertension. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1517–1525. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.13.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sobolewski A, Rudarakanchana N, Upton PD, Yang J, Crilley TK, Trembath RC, Morrell NW. Failure of bone morphogenetic protein receptor trafficking in pulmonary arterial hypertension: potential for rescue. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3180–3190. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishanian TG, Waldman T. Interaction of the BMPR-IA tumor suppressor with a developmentally relevant splicing factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;323:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watanabe H, Shionyu M, Kimura T, Kimata K, Watanabe H. Splicing factor 3b subunit 4 binds BMPR-IA and inhibits osteochondral cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20728–20738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]