Abstract

Innate immune activation was a strong predictor of HIV acquisition in women at risk for HIV in CAPRISA004. Identifying the cause/s of activation could enable targeted prevention interventions. In this study, plasma concentrations of lipopolysaccharide, soluble CD14 and intestinal fatty-acid binding protein did not differ between subjects who did or did not subsequently acquire HIV, nor were these levels correlated with plasma cytokines or natural killer cell activation. There was no difference between HIV-acquirers and non-acquirers in the chemokine and cytokine responses of peripheral blood mononuclear cells stimulated with TLR2, 4 or 7/8 agonists. Further studies are required.

Keywords: HIV, microbial translocation, LPS, sCD14, I-FABP, TLR2, TLR4, TLR7/8, immune activation

Introduction

Non-specific activation of the immune system is a pathological feature of HIV infection1. The degree of activation of CD8+ T-cells is associated with the rate of HIV disease progression2. But our recent studies3 validate previous studies 4-6 in suggesting that innate immune activation is also a pathological determinant of HIV acquisition. In CAPRISA004, a randomized placebo-controlled trial of 1% Tenofovir gel, women who acquired HIV had significantly higher plasma levels of interleukin(IL)-2, IL-7, IL12p70 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and more frequent activation and degranulation of Natural Killer (NK) cells in the blood than women who remained uninfected3. Even after adjusting for potential confounders, innate immune activation was associated with HIV acquisition. The identification of determinants of activation would allow for the design and testing of targeted interventions to reduce activation as a method to reduce HIV acquisition.

During established HIV infection, increased microbial translocation1 and chronic Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection7 are associated with greater immune activation. There has been some speculation that a higher pathogen burden in settings with poorer sanitation may result in higher levels of microbial translocation, even amongst HIV-uninfected individuals8. Others have suggested that differences in toll-like receptor (TLR) responsiveness exist between women who are exposed to HIV but remain uninfected, and HIV-uninfected controls9. We previously reported that the prevalence of CMV infection in this cohort is almost universal3 so this is not likely to drive the differences. Although HSV-2 was associated with HIV acquisition and suppressed NK cell antiviral response10, it did not weaken the association between innate immune activation and HIV acquisition3. Here we report on further studies that aimed to determine whether differences in microbial translocation or TLR responsiveness could explain differences in innate immune activation in women who were exposed to HIV in CAPRISA004.

Methods

Study population and sampling

For this study, specimens from women who acquired HIV and women who remained HIV-uninfected were used. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells and plasma were collected from participants of CAPRISA004, a randomized controlled trial of 1% Tenofovir gel conducted in eThekweni and Vulindlela, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, as previously described11. The participants in this study matched those used in previous studies of immune activation in this trial3. Briefly, samples from HIV acquirers were from the last trial visit prior to HIV acquisition. Samples from HIV non-acquirers were from the trial visit at which sexual activity in the preceding month was each participant’s personal maximum. HIV non-acquirers were eligible for selection if they reported an average of more than two sex-acts per week throughout the trial, returned a corresponding number of used gel applicators (as a surrogate measure of actual sexual activity), had PBMC samples available and had given informed consent for future research. HIV-uninfected status was verified by PCR, Western blot and rapid antibody assays. Due to limited cell numbers, a different number of samples were used for each TLR agonist studied (n=16 acquirers and n=13 non acquirers for aldrithiol-inactivated HIV [AT-2], n=14 and n=9 respectively for heat-killed Listeria monocytgenes [HKLM] and n=10 and n=6 for lipopolysaccharide 12). The baseline demographic characteristics, sexual history and study procedures have been previously described3. Receipt of Tenofovir gel did not affect any of the measures presented3,13 so is not further described in this report.

This study was approved by the University of KwaZulu-Natal Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (#BE073/010). Participants gave informed consent for their samples to be used for these studies.

Measurement of Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), soluble CD14 (sCD14) and intestinal fatty-acid binding protein (I-FABP)

LPS, sCD14 (a marker of monocyte response to LPS), and I-FABP (a marker of enterocyte damage) were measured in duplicate in cryopreserved plasma from participants. Plasma had not been thawed more than once prior. LPS levels were measured using the Limulus amebocyte assay (Lonza, USA) as previously described14. A commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was used for sCD14 (R&D Systems, USA) on plasma diluted to 0.5% according to the manufacturer’s instructions. I-FABP was measured using an adaptation of FABP2 kit on plasma diluted to 10% in 50% fetal calf serum in phosphate buffered saline (R&D Systems, USA).

Natural Killer cell phenotypic characterization

Natural Killer (NK)-cell activation was measured in cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in batch analyses using optimized procedures and flow cytometry methods as previously described3.

Characterization of cytokine and chemokine response of PBMC to TLR agonists

Cryopreserved PBMC were thawed in warm R10 culture media: RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen), 2 mmol/L of L-glutamine and 1% penicillin/ streptomycin. After two hours of incubation at 37°C, cells were stained with Viacount (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA) and counted with a Guava PCA (Millipore). PBMC were resuspended at 1 × 106/ml in R10 culture media. TLR agonists, or R10 media alone were added to 1 × 106 PBMC in 4ml FACSTubes (BD) at the following concentrations 0.7μg/ml AT-2 HIV, 2μl/ml HKLM or 0.1μg/ml LPS. Cells were cultured overnight at 37°C in a sterile incubator maintained at 5% CO2. Supernatant was harvested by centrifugation and immediately cryopreserved at −80°C.

The concentrations of 13 cytokines: GMCSF, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12 (p70), IL-13, and TNF-α were assessed using a high sensitivity human cytokine premixed 13-plex kit (Millipore) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were assayed in duplicate after a single thaw, without dilution. Samples from HIV acquirers and HIV non-acquirers were equally spread across assay plates to minimize plate-to-plate variability as a confounder. Cytokine measures beneath the detection limit of the assay were given a value of the midpoint between zero and the lower detection limit of the assay and were included in the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Assays were conducted blinded to whether the sample was from an HIV acquirer or non-acquirer. The study had 80% power to detect a difference of approximately 4pg/ml in LPS, 0.17 × 106 pg/ml in sCD14 or 208 pg/ml in I-FABP levels between the two groups.

Comparisons were made using a non-parametric Mann-Whitney test in GraphPad Prism v5 (GraphPad Software). To account for multiple comparisons the unadjusted p-value is reported and the relevant Bonferroni-adjusted p-value is given in the text or figure caption.

Results

HIV-exposed women who acquired HIV whilst enrolled in CAPRISA004 were previously reported to have higher levels of circulating IL-2, IL-7, IL12p70 and TNF-α in the blood, and higher levels of activated NK cells relative to women who did not acquire HIV3. To explore possible explanations for the differences in activation, samples from the same 44 women who acquired HIV and 37 who remained uninfected and were previously studied, were evaluated for evidence of microbial translocation or differential response to microbial products. The baseline characteristics of this study population have been previously described3.

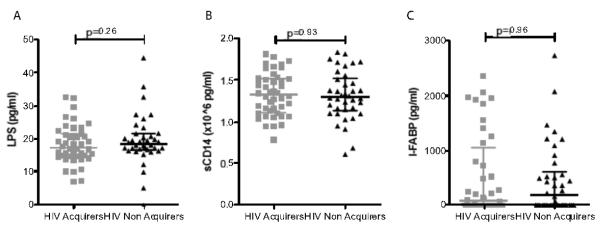

No appreciable difference in microbial translocation between HIV acquirers and HIV non-acquirers

In primary or chronic HIV infection, plasma levels of LPS are a marker of gut-permeability and microbial translocation1. Both LPS and its ligand sCD14 are associated with immune activation in HIV infection. We measured LPS, sCD14 and I-FABP- a marker of enterocyte damage15. There was no significant difference in plasma levels of LPS, sCD14 or I-FABP in HIV acquirers and non-acquirers, although surprisingly, some of the clinically-well participants had high levels of LPS or I-FABP consistent with significant translocation or intestinal epithelial cell necrosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Plasma levels of LPS (A), sCD14 (B) and I-FABP (C) do not differ between women who acquired HIV samples pre-infection (grey squares) and women who remained HIV uninfected (black triangles). Lines demarcate the median and interquartile range. p-value from Mann-Whitney test.

Levels of LPS, sCD14 and I-FABP were not associated with NK cell activation, regardless of which marker of NK cell activation was used (HLA-DR, CD38, or CD69), as shown in Supplementary Figure 1. Similarly, levels of LPS, sCD14 or I-FABP were not significantly associated with any of the plasma cytokines measured in previous studies after correcting for multiple comparisons (the Bonferroni-corrected alpha for significance was p<0.0013).

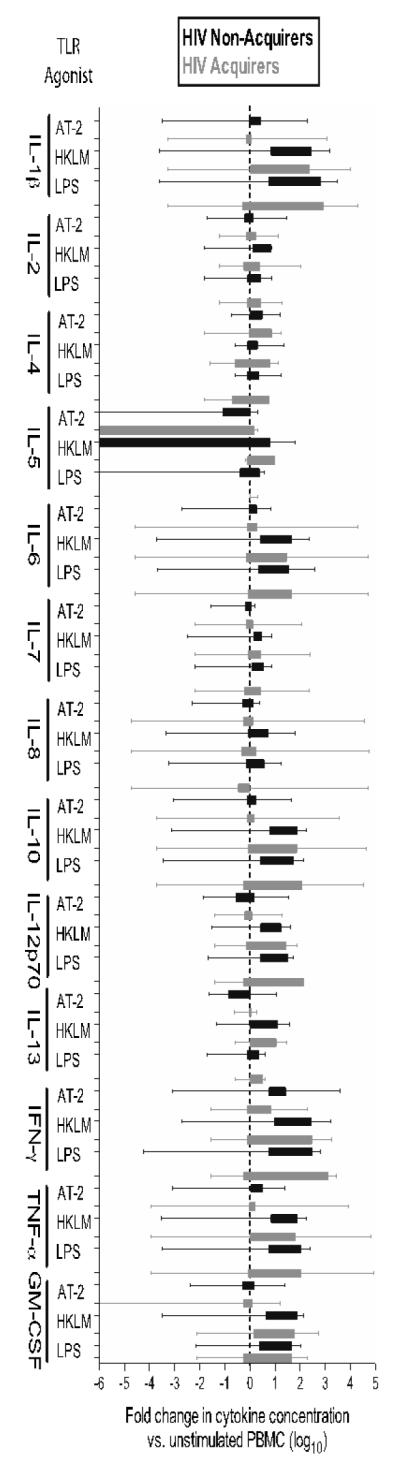

TLR responsiveness

Some previous studies have suggested that differences in the ability to respond to microbial products may lead to differential levels of TLR-mediated activation9. To determine whether there were abt differences in TLR responsiveness between HIV-acquirers (n=21) and HIV non-acquirers (n=18), cytokine and chemokine release was quantified after overnight in vitro culture of PBMC with agonists for TLR2 (HKLM), TLR4 (lipopolysaccharide, LPS) or TLR7/8 (AT-2 HIV).

Neither the absolute increase in concentration nor the fold-change increase in concentration relative to media alone of any of the measured cytokines differed between PBMC from HIV acquirers and non-acquirers stimulated with a TLR2, TLR4 or TLR7/8 agonist (Figure 2). IFN-γ concentrations were higher in the supernatant of PBMC from HIV acquirers cultured with AT-2 HIV (p=0.05), but after adjusting for the 39 comparisons made, the difference was not significant.

Figure 2.

PBMC from HIV acquirers (black) and HIV non-acquirers (grey) exhibit a similar fold change (log10) in the secretion of chemokines and cytokines after stimulation with a TLR7/8 agonist (aldrithiol inactivated virus, AT-2 HIV), TLR2 agonist (heat-killed Listeria monocytgenes, HKLM) or a TLR4 agonist lipopolysaccharide, LPS) relative to media alone. 1 × 106 PBMC were stimulated with the agonist shown overnight and cytokines/chemokines measured by Luminex in duplicate. Data are shown as box and whiskers to 5th and 95th percentile. Adjusted p-values are not shown as none achieved significance although the nominal p-value for the comparison of IFN-secretion after AT-2 stimulation in HIV acquirers and non-acquirers was p=0.05 (Bonferroni-adjusted p<0.0013 for significance).

Chronic stimulation by LPS is thought to reduce further responsiveness to stimulation of TLR4 by LPS (‘LPS tolerance’)16. In this study there was no evidence that circulating LPS levels were associated with in vitro cytokine or chemokine responses of PBMC stimulated with LPS (Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

Immune activation was a potent predictor of HIV acquisition in CAPRISA0043. In chronic HIV infection, immune activation is associated with circulating levels of microbial products1, which predict disease course1,14. To our knowledge, there have not been any previous studies of microbial translocation in women who are exposed to HIV. Here we found that microbial translocation was similar amongst HIV acquirers and non-acquirers. Microbial translocation was, furthermore, not associated with NK cell activation or any of the cytokines measured. We speculate that the levels of microbial translocation measured in HIV acquirers and non-acquirers may represent homeostatic levels and an alternative more potent mediator of activation may remain undiscovered amongst HIV acquirers. We tested an alternative hypothesis that TLR responsiveness may differ amongst HIV acquirers and non-acquirers. In this study there was no significant difference in PBMC response to TLR agonists, whereas a previous report found greater TLR responsiveness in HIV exposed uninfected women compared with healthy blood donors9. The difference may be due to the comparison group in our study being women who actually acquired infection.

We observed that PBMC from HIV acquirers produced more of the antiviral cytokine, IFN-γ, after stimulation with AT-2 HIV than HIV non-acquirers. Although this finding is likely due to chance, as it did not reach statistical significance after controlling for the multiple tests performed, the finding points to the possibility that women who later acquired HIV may have had sustained exposure to HIV and consequently developed an HIV-specific immune response in the absence of infection. As reported elsewhere17, we did not detect sustained or robust HIV-specific T-cell responses by ELISPOT in these participants. Therefore HIV-specific responses, if present in these women, are weak. Assessments of HIV-specific immune responses in future studies of HIV acquisition continue to be warranted.

Our findings are limited by the sample size; we are unable to rule out a difference smaller than what the study was designed to detect. Moreover, we studied bulk PBMC and plasma. Studies in established HIV infection have demonstrated that TLR responsiveness is cell-type, disease-stage and agonist-specific18. Moreover, measurement of these parameters in the periphery may be inadequate to reveal what actually happens in the female genital tract, the site of infection, and therefore a study of the mucosa would perhaps be appropriate in future work19.

These data collectively suggest that neither microbial translocation nor TLR responsiveness of PBMC are sufficient to explain the higher levels of innate immune activation observed in women who subsequently acquired HIV in CAPRISA004. Further studies to explore host genetic factors or differences in the enteric or genital tract microbiome may be required in order to identify the upstream causes of pre-existing immune activation in women who subsequently acquired HIV in CAPRISA004.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants; women whose dedication and commitment to improving their and their peers’ health and kindly donating samples during the conduct of the trial make this research possible. We acknowledge the work of the study staff of CAPRISA 004 and the TRAPS team: Sengeziwe Sibeko, Leila Mansoor, Lise Werner, Shabashini Sidhoo and Natasha Arulappan. We gratefully acknowledge Rachel Simmons for advice on cytokine assays, Marianne Mureithi for advice on designing TLR responsiveness assays and Raveshni Durgiah for technical assistance.

Funding This work was supported by the South African HIV/AIDS Research Platform (SHARP), and US National Institutes for Health FIC K01-TW007793. The parent trial (CAPRISA 004) was supported by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), FHI360([USAID co-operative agreement # GPO-A-00-05-00022-00, contract # 132119), and the Technology Innovation Agency (LIFElab) of the South African government’s Department of Science & Technology. Tenofovir was provided by Gilead Sciences and the gel was manufactured and supplied for the CAPRISA 004 trial by CONRAD. The current studies are part of the CAPRISA TRAPS (Tenofovir gel Research for AIDS Prevention Science) Program, which is funded by CONRAD, Eastern Virginia Medical School (USAID co-operative grant #GP00-08-00005-00, subproject agreement # PPA-09-046). The views expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, Gilead Sciences, Eastern Virginia Medical School or CONRAD. We thank the US National Institutes for Health’s Comprehensive International Program of Research on AIDS (CIPRA grant # AI51794) for the research infrastructure. VN was supported by LIFELab and the Columbia University-South Africa Fogarty AIDS International Training and Research Program (AITRP, grant #D43 TW000231). . WHC was supported by a Massachusetts General Hospital Physician Scientist Development Award. TN holds the South African Department of Science and Technology/National Research Foundation Research Chair in Systems Biology of HIV/AIDS and is also supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. MA is a Distinguished Clinical Scientist of the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. DCD, NGS and AR were supported by the intramural program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author’s contributions All the authors contributed to the design of the sub-study. V.N. designed the study. V.N., N.S. and N.S designed and executed the experiments, performed the data collection and analysis. T.N., M.A., D.D., and S.S.A.K supervised the data collection. S.S.A.K. and Q.A.K designed, conducted and analysed the parent CAPRISA 004 trial. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript

Conflict of Interest: SSAK and QAK were the co-Principal Investigators of the CAPRISA 004 trial of tenofovir gel. SSAK and QAK are also co inventors of two pending patents (61/354.050 and 61/357,892) of tenofovir gel against HSV-1 and HSV-2 with scientists from Gilead Sciences. Gilead Sciences did not have any role in the experiments or analyses presented here.

Clinical trials registration number of parent trial: NCT00441298.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sandler NG, Douek DC. Microbial translocation in HIV infection: causes, consequences and treatment opportunities. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012 Aug 13;10(9):655–666. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giorgi JV, Liu Z, Hultin LE, Cumberland WG, Hennessey K, Detels R. Elevated levels of CD38+ CD8+ T cells in HIV infection add to the prognostic value of low CD4+ T cell levels: results of 6 years of follow-up. The Los Angeles Center, Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993 Aug;6(8):904–912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naranbhai V, Abdool Karim SS, Altfeld M, et al. Innate Immune Activation Enhances HIV Acquisition in Women, Diminishing the Effectiveness of Tenofovir Microbicide Gel. J Infect Dis. 2012 Oct;206(7):993–1001. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Begaud E, Chartier L, Marechal V, et al. Reduced CD4 T cell activation and in vitro susceptibility to HIV-1 infection in exposed uninfected Central Africans. Retrovirology. 2006;3:35. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLaren PJ, Ball TB, Wachihi C, et al. HIV-exposed seronegative commercial sex workers show a quiescent phenotype in the CD4+ T cell compartment and reduced expression of HIV-dependent host factors. J Infect Dis. 2010 Nov 1;202(Suppl 3):S339–344. doi: 10.1086/655968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jennes W, Evertse D, Borget MY, et al. Suppressed cellular alloimmune responses in HIV-exposed seronegative female sex workers. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006 Mar;143(3):435–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deeks SG. HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:141–155. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042909-093756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Redd AD, Dabitao D, Bream JH, et al. Microbial translocation, the innate cytokine response, and HIV-1 disease progression in Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Apr 21;106(16):6718–6723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901983106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biasin M, Piacentini L, Lo Caputo S, et al. TLR activation pathways in HIV-1-exposed seronegative individuals. J Immunol. 2010 Mar 1;184(5):2710–2717. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naranbhai V, Altfeld M, Abdool Karim Q, Ndung’u T, Abdool Karim SS, Carr WH. Natural killer cell function in women at high risk for HIV acquisition: insights from a microbicide trial. Aids. 2012 Sep 10;26(14):1745–1753. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328357724f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science. 2010 Sep 3;329(5996):1168–1174. doi: 10.1126/science.1193748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamann L, Kumpf O, Schuring RP, et al. Low frequency of the TIRAP S180L polymorphism in Africa, and its potential role in malaria, sepsis, and leprosy. BMC Med Genet. 2009;10:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mureithi MW, Poole D, Naranbhai V, et al. Preservation HIV-1-specific IFNgamma+ CD4+ T-cell responses in breakthrough infections after exposure to tenofovir gel in the CAPRISA 004 microbicide trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012 Jun 1;60(2):124–127. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824f53a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandler NG, Wand H, Roque A, et al. Plasma levels of soluble CD14 independently predict mortality in HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2011 Mar 15;203(6):780–790. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evennett NJ, Petrov MS, Mittal A, Windsor JA. Systematic review and pooled estimates for the diagnostic accuracy of serological markers for intestinal ischemia. World J Surg. 2009 Jul;33(7):1374–1383. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biswas SK, Lopez-Collazo E. Endotoxin tolerance: new mechanisms, molecules and clinical significance. Trends Immunol. 2009 Oct;30(10):475–487. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burgers WA, Muller TL, Kiravu A, et al. Infrequent, low magnitude HIV-specific T -cell responses in HIV-uninfected participants in the 1% Tenofovir microbicide geltrial (CAPRISA004) Retrovirology. 2012;9(Suppl 2):2250. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang JJ, Lacas A, Lindsay RJ, et al. Differential regulation of toll-like receptor pathways in acute and chronic HIV-1 infection. Aids. 2012 Mar 13;26(5):533–541. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834f3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts LPJ, Williamson C/, Little F, Naranbhai V, Sibeko S, Walzl G, Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS. Genital Tract Inflammation in Women Participating in the CAPRISA TFV Microbicide Trial Who Became Infected with HIV: A Mechanism for Breakthrough Infection?. Paper presented at: 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston, MA, USA. 27 February 2011-2 March 2011.2011. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.