Abstract

Background

Self-regulatory mechanisms appear etiologically operant in the context of both substance use disorders (SUD) and bipolar disorder (BD), however, little is known about the role of deficits in emotional self-regulation (DESR) as it relates to SUD in context to mood dysregulation. To this end, we examined to what extent DESR was associated with SUD in a high-risk sample of adolescents with and without BD.

Methods

203 families were assessed with a structured psychiatric interview. Using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), a subject was considered to have DESR when he or she had an average elevation of 1 standard deviation (SD) above the norm on 3 clinical scale T scores (Attention, Aggression, and Anxiety/Depression; scores: 60×3 ≥180).

Results

Among probands and siblings with CBCL data (N=303), subjects with DESR were more likely to have any SUD, alcohol use disorder, drug use disorder, and cigarette smoking compared to subjects with scores<180 (all p values <0.001), even when correcting for BD. We found no significant differences in the risk of any SUD and cigarette smoking between those with 1 SD and 2 SD above the mean (all p values >0.05). Subjects with cigarette smoking and SUD had more DESR compared to those without these disorders.

Conclusions

Adolescents with DESR are more likely to smoke cigarettes and have SUD. More work is needed to explore DESR in longitudinal samples.

Keywords: juvenile bipolar disorder, substance use disorders, dysregulation, CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist, deficits in emotional self-regulation, DESR, adolescents, bipolar disorder, BD, cigarettes, tobacco

1. INTRODUCTION

Pediatric-onset bipolar disorder (BD) is thought to occur in approximately 3% of youth (Merikangas et al., 2010) and is associated with substantial impairment and comorbidity (Axelson et al., 2006; Biederman et al., 2005; Carlson et al., 2000; Findling et al., 2001; Geller et al., 2002; Kowatch et al., 2005; McClellan et a., 2007; Wilens et al., 2008) An emerging literature suggests that pediatric-onset BD may be a particularly high risk group for cigarette smoking and SUD.(Biederman et al., 1997; Carlson et al., 2000; Delbello et al., 2007; Geller et al., 2008; Goldstein et al., 2008a; Goldstein et al., 2008b; West et al., 1996; Wilens et al., 1997, 2008; Wills et al., 1995; Young et al., 1995) An excess of SUD has been reported in adolescents with BD or prominent mood lability.(Biederman et al., 1997; Carlson et al., 2000; Delbello et al., 2007; Geller et al., 2008; Goldstein et al., 2008a, 2008b; West et al., 1996; Wilens et al., 1997, 2008; Wills et al., 1995; Young et al., 1995) For example, we previously reported that 34% of BD adolescents at a mean age of 14 years already met criteria for SUD compared to 4% of similarly aged control youth (OR=2.8, p<0.004) and that this association was not accounted for by comorbid conduct disorder(Wilens et al., 2008, 2009). Conversely, BD has also been reported to be over-represented in youth with SUD (Biederman et al., 1997; Weinberg and Glantz, 1999; West et al., 1996; Wilens et al., 1997; Wills et al., 1995; Young et al., 1995). Hence, a bidirectional relationship between pediatric BD and cigarette smoking /SUD exists although the mechanism(s) linking this association remain unclear.

Self-regulatory mechanisms may be an important factor within the context of SUD and youth with BD (Lorberg et al., 2010). One dimensional domain critical in the study of psychopathology and SUD is deficits in emotional self-regulation (DESR). While a myriad of definitions exist for DESR, what appears to be common among them is DESR being defined by affect, emotional lability, reactivity, irritability and lack of self-regulation of such emotions (Althoff et al., 2010; Cheetham et al., 2010). One useful measure of DESR in children is the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), one of the most commonly used measures of child psychopathology (Achenbach, 1991). Our group and others have identified a unique continuous profile within the empirically derived CBCL consisting of elevated scores (at least 1 standard deviation [SD] above the norm: 60×3≥180 combined) on three clinical scales: Anxiety/Depression, Attention, and Aggression (AAA; Althoff et al., 2010a, 2010b; Biederman et al., 2012). A profile of >2 SD elevation in these clinical scales has been referred to as the “Dysregulation Profile” (Althoff et al., 2010a) and is synonymous with more severe DESR.

DESR correlates with psychopathology including disruptive, mood, and anxiety disorders; children with DESR have been found to be at risk for suicidal behavior and psychiatric hospitalization (Althoff et al., 2010a; Biederman et al., 1995; Gratz and Roemer, 2004; Reimherr et al., 2005). DESR has also been purported to be important in pediatric BD (Biederman et al., 1995; Gratz and Roemer, 2004), although DESR is nonspecific to mood disorders. For instance, DESR has been associated variably with Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct and oppositional defiant disorders (Barkley et al., 2008), all of which are frequently comorbid with BD (Wilens et al., 2008). Adults with DESR manifest a lower quality of life, worse social adjustment, elevated traffic accidents and criminality (Surman et al., 2010).

Recent work has also highlighted the role of DESR in cigarette smoking and SUD (Aguilar de Arcos et al., 2008; Cheetham et al., 2010; Dorard et al., 2008; Gonzalez et al., 2008). For instance, Gonzalez et al. (2008) showed DESR to be related to an enhanced motivation to smoke and greater perceived barriers to quitting. DESR has also been shown to be related to the motivation for, and regular use of marijuana (Bonn-Miller et al., 2008; Dorard et al., 2008). Similarly, more DESR has been shown in current opioid abusers (Aguilar de Arcos et al., 2008), present even while patients are in remission. This calls in to question whether DESR represents a stable trait of the patient that may then be subsequently related to the development of SUD. Interestingly, an analysis of 325 at risk infants followed for 19 years showed that a CBCL proxy of DESR did not predict any particular psychiatric disorder, but was associated with SUD, suicidality and poorer overall functioning (Holtmann et al., 2011). Despite these studies, relatively little is known about the relationship of DESR as it relates to SUD in high-risk samples of adolescents with severe affective illness.

Since DESR represents an indicator of very high affective reactivity that is variably related to BD,(Althoff et al., 2010a; Biederman et al., 1995; Gratz and Roemer, 2004; Holtmann et al., 2011) it may represent an important dimensional construct that may also be related to a higher risk or earlier-onset of SUD. Given that DESR is measurable from an early age through the use of questionnaires like the CBCL, it may be possible to identify specific youth who, by nature of the DESR, may be at high risk to develop SUD. Such identification has important clinical and scientific implications. Clinically, the identification of specific youth at very high risk for SUD by nature of DESR is critical for prevention of SUD particularly given that psychosocial and pharmacological interventions exist for DESR. Scientifically, the examination of neurocircuitry related to DESR (Leibenluft et al., 2003, 2007) may further our understanding of the etiologies of SUD.

To this end, we used the CBCL to examine DESR in a high-risk sample of BD youth, non-mood disordered controls, and their siblings. We hypothesized that high levels of DESR would be associated with a higher risk for cigarette smoking and SUD. Secondarily, we hypothesized that DESR severity would be associated with the risk for cigarette smoking and SUD: the group with a combined CBCL-AAA score of 1 SD above the mean would be associated with a higher risk for SUD than those without DESR, but with a lower risk than those with scores of 2 SD above the mean.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The current analyses are based on baseline assessments of our ongoing, case-controlled longitudinal family study of BD adolescents (our sample was evenly split between BPD I and II (51% and 49%, respectively; Wilens et al., 2008). The methods of the study are described in full detail elsewhere (Wilens et al., 2008). Briefly, female and male subjects aged range 10-18 years with BD and without a mood disorder and their first-degree relatives were ascertained from both community and clinical sources. We excluded any youth with major sensorimotor handicaps (paralysis, deafness, blindness), autism, inadequate command of the English language, or a Full Scale IQ less than 70. We excluded controls with any mood disorder including dysthymia or unipolar depression secondary to concerns of “manic switching” from dysthymia or unipolar depression to BD (Strober and Carlson, 1982). Due to the family nature of this study, potential subjects were also excluded if they had been adopted, or if their nuclear family was not available for study. Parents provided written informed consent for their children and children provided written assent to participate. The institutional review board at Massachusetts General Hospital approved this study and a federal certificate of confidentiality was obtained.

A two-stage ascertainment procedure selected subjects. For BD probands, the first stage confirmed the diagnosis of BD by screening all children using a telephone questionnaire with their primary caregiver. The second stage was the structured psychiatric interview as described below. Only subjects who received a positive diagnosis at both stages were included in the sample. We also screened potential non-mood disordered controls in two stages. First, control mothers responded to the telephone questionnaire, then eligible controls meeting study entry criteria were recruited for the study and received the diagnostic assessment with a structured interview. Only subjects classified as not having any mood disorder at both stages were included in the control group. All BD and control probands were assessed using structured psychiatric interviews for the full presence of DSM-IV BD or for the absence of any mood disorder (controls).

2. 1 Assessments

All assessments for psychiatric and substance use disorders used DSM-IV-based structured interviews given by raters with bachelor’s or master’s degrees in psychology who had been extensively trained and supervised by the senior investigators. Raters were blind to the ascertainment status of the probands. Assessments for subjects under 18 years of age relied on the DSM-IV Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders-Epidemiologic Version (KSADS-E; Ambrosini, 2000) and for subjects 18 years and older relied on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First et al., 1997) Interview structure included independent interviews with mothers and direct interviews with probands and controls.

SUD and cigarette smoking were diagnosed on the basis of DSM-IV criteria using the KSADS-E and SCID. To meet a positive diagnosis of cigarette smoking, subjects under 18 needed to endorse any amount of smoking daily, whereas subjects over 18 needed to endorse smoking at least a pack of cigarettes per day. If either parent endorsed full criteria for a psychiatric disorder or SUD during his/her SCID, then the family history of the proband was considered positive.

All cases were presented to a committee composed of board certified child psychiatrists and licensed psychologists. Diagnoses presented for review were considered positive only if the diagnosis would be considered clinically meaningful due to the nature of the symptoms, the associated impairment, and the coherence of the clinical picture. Discrepant reports were reconciled using the most severe diagnosis from any source unless the diagnosticians suspected that the source was not supplying reliable information. In addition to assessment of abuse and dependence, subjects were queried for any use of illicit drugs during the non-alcohol SUD module of the structured interview. All cases of suspected drug or alcohol abuse or dependence were further reviewed with a child and adult psychiatrist with additional addiction credentials. Similar to our previous work, we limited our cases to moderate or severe SUD (Wilens et al., 2008).

To assess the reliability of our diagnostic procedures, we computed kappa coefficients of agreement by having three experienced, board-certified child and adult psychiatrists diagnose subjects from audio taped interviews made by the assessment staff. Based on 500 assessments from interviews of children and adults, the median kappa coefficient was 0.98. Kappa coefficients for individual diagnoses included: major depression (1.0), mania (0.95), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; 0.88), conduct disorder (CD; 1.0), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD; 0.90), antisocial personality disorder (ASPD; 0.80), and substance use disorder (1.0).

2.2 Child Behavior Checklist

The parent (usually the mother) of each participant completed the Child Behavior Checklist for ages 4 to 18 years (CBCL/4-18; Achenbach, 1991). The CBCL is an affordable pencil and paper test completed by the child’s caregiver, requiring no administration by a physician or rater. The CBCL queries the parent about the child’s behavior in the past six months and aggregates this data into behavioral problem T-scores (Achenbach, 1991). A computer program calculates the T-scores for each scale. Raw scores are converted to gender and age standardized scores (T-scores having a mean=50 and SD=10). A minimum T-score of 50 is assigned to scores that fall at midpoint percentiles of ≤50 on the syndrome scales to permit comparison of standardized scores across scales.

2.3 CBCL-DESR and CBCL-Severe Dysregulation Profiles

The CBCL-DESR was defined as positive by a score of ≥180 (≥60 on average on each scale), but <210 (average T score of ≥60 and <70 on AAA scales; Biederman et al., 2012) For example, a subject with an Attention T-score of 55, an Aggression T-score of 65, and an Anxious/Depressed T-score of 75 would meet criteria for the CBCL-DESR profile (sum of 195 on all three scales). As described previously, the CBCL-Severe Dysregulation profile (Biederman et al., 2012, 2009) was defined as positive by a score of ≥210 (2SDs) on the sum of the Attention, Aggression, and Anxious/Depressed CBCL scales (AAA profile).

2.4 Statistical Analysis

We compared the demographic and clinical characteristics between the three groups (no DESR; DESR 1SD (≥180, <210); DESR 2SD (≥210)) using analysis of variance for continuous outcomes, the Kruskal Wallis test for SES, and logistic regression for binary outcomes.

We used Kaplan Meier Curves and Cox Proportional Hazard models to assess the occurrence of SUD across the three groups. If there were no differences between the DESR groups, we collapsed across these groups and examined occurrence of SUD between those with and without DESR. We used logistic regression to compare the severity of the substance use disorders (moderate vs. severe) across the three groups. We used linear regression to compare the onsets of the SUDs across the three DESR groups and we also used linear regression to compare the CBCL AAA scores of subjects across the SUD groups. We calculated all statistics using STATA 12.0. All statistical tests are two-tailed. Across all models, we used robust estimates of variance to account for the non-independence of the sample resulting from the correlation between family members. We used a p-value threshold of 0.05 to assert statistical significance. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise specified.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Demographics

The final sample included 303 subjects: no DESR (N=210), scores of ≥180, <210 on CBCL-AAA (N=50), and scores of ≥210 (N=43). We found no significant differences between the groups on age, socioeconomic status, or sex characteristics (see Table 1, all p values > 0.05). We did find a significant difference in the percent of subjects with a family history of SUD (p=0.03); and as a result, all analyses examining offspring SUD were adjusted by family history of SUD.

Table 1.

Differences in subjects with CBCL scores <180, >=180 and <210, and >=210 (N=303).

| CBCL <180 N=210 |

>=180, <210 N=50 |

>=210 N=43 |

Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| Age | 13.4 ± 2.9 | 12.9 ± 2.2 | 13.8 ± 2.6 | F (2, 300)=1.23, p=0.3 |

| SES | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 1.7 ± 1.3 | 1.9 ± 1.3 | χ2 (2)=0.7, p=0.7 |

| N(%) | N (%) | N(%) | ||

| Sex (% male) | 113 (54) | 34 (68) | 25 (58) | χ2 (2)=3.4, p=0.19 |

| Family History of SUD | 112 (53) | 31 (62) | 32 (74) | χ2 (2)=6.9, p=0.03 |

| School Functioning | ||||

| Repeated a Grade | 19 (9) | 5 (10) | 6 (14) | χ2 (2)=0.7, p=0.7 |

| Special Class | 19 (9) | 17 (34)a | 18 (42)a | χ2 (2)=31.4, p<0.001 |

| Extra Help | 74 (35) | 31 (62)a | 32 (74)a | χ2 (2)=28.5, p<0.001 |

| IQ | 108.7 ± 14.8 | 100.2 ± 15.4a | 99.0 ± 3.0a | F (2, 282)=11.6, p<0.0001 |

| GAF | 59.9 ± 9.3 | 42.9 ± 8.6a | 39.4 ± 5.8a | F (2, 300)=147.1, p<0.001 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Bipolar Disorders | 13 (6) | 26 (52)a | 35 (81)ab | χ2 (2)=134.0, p<0.001 |

| Multiple Anxiety Disorders | 42 (20) | 22 (44)a | 33 (77)ab | χ2 (2)=56.8, p<0.001 |

| ADHD | 33 (16) | 39 (78)a | 34 (79)a | χ2 (2)=111.7, p<0.0001 |

| Conduct Disorder | 11 (5) | 21 (42)a | 28 (65)a | χ2 (2)=99.2, p<0.001 |

vs. <180; p<0.05

vs. >=180,<210; p<0.05

ADHD=Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

3.2 Comorbidity and School Functioning

Compared to those without elevations in the CBCL (<180), we found that there was a higher risk for psychiatric disorders in subjects with 1 SD (>=180, <210) and 2 SD (>=210) above the mean on the CBCL for BD, ADHD, multiple anxiety, and conduct disorders (see Table 1). Among school related items, we found that subjects with DESR were more likely to have taken a special class and to have received extra help than subjects without DESR. We found no significant differences between the groups with 1SD and 2 SD (all p values > 0.05).

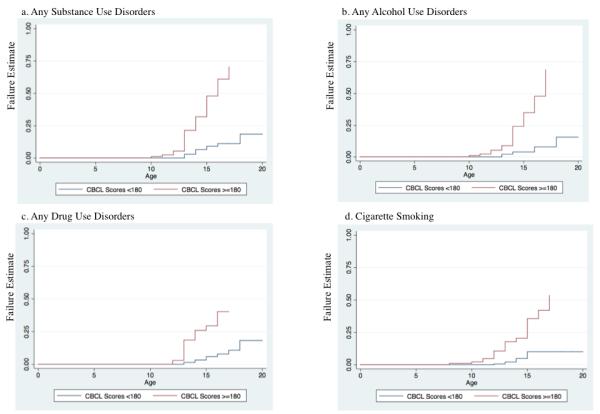

3.3 Relationship of DESR and SUD

We initially examined whether there were any differences among the groups with no DESR, DESR with 1 SD and DESR with 2 SD on CBCL-AAA scores in relation to SUD. While we found significant differences between those with DESR and those without DESR, we found no significant differences between the DESR 1SD and DESR 2 SD groups on SUD outcomes (all p values > 0.05); therefore, we collapsed these groups, and subsequently looked at our main findings comparing two groups (those with DESR vs. those without DESR; see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Morbid Risk of Substance Use Disorders (moderate or severe) and Cigarette Smoking (N=303).

Compared to those without DESR, those with DESR (>=180 ) were more likely to endorse alcohol use disorders (HR: 9.0, 95% CI: 3.7, 22.2; p<0.001), drug use disorders (HR: 6.2, 95% CI: 2.9, 13.3; p<0.001), any SUD (HR: 7.3, 95% CI: 3.6, 14.8; p<0.001), and more likely to smoke cigarettes (HR: 5.7, 95% CI: 2.7, 12.0; p<0.001). When we included BD in the model, all associations remained significant (all p values <0.05). When we added both BD and ADHD in the models, all associations remained significant (all p values <0.05). When we included BD, ADHD, and CD in the model, the association lost significance (all p values >0.05). Further, when we only included CD in the original model, the associations for alcohol use disorders, drug use disorders, and cigarette smoking lost significance (all p values >0.05).

When we examined the demographics, comorbidity, and school functioning between the two groups, we found no significant differences from the results that included three groups (see Table 2). Those with DESR were more likely than those without DESR to endorse alcohol use disorders (22% vs. 4%; HR: 5.3, 95% CI: 2.3, 12.1; p<0.001), drug use disorders (18% vs. 4%; HR: 5.3, 95% CI: 2.3, 12.1; p<0.001), any SUD (27% vs. 6%; HR: 6.2, 95% CI: 2.9, 13.3; p<0.001), and more likely to smoke cigarettes (20% vs. 5%; HR: 5.1, 95% CI: 2.2, 11.4; p<0.001).

Table 2.

Differences in subjects with CBCL scores <180, and >=180 (N=303).

| CBCL <180 N=210 |

≥180 N=43==93 |

Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| Age | 13.4 ± 2.9 | 13.3 ± 2.4 | t=0.2, p=0.8 |

| SES | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 1.3 | z=0.8 |

| N(%) | N(%) | ||

| Sex (% male) | 113 (54) | 59 (63) | χ2 =2.4, p=0.11 |

| Family History of SUD | 112 (53) | 63 (68) | χ2 =5.5 p=0.02 |

| School Functioning | |||

| Repeated a Grade | 19 (9) | 11 (12) | χ2=0.6, p=0.5 |

| Special Class | 19 (9) | 35 (38) | χ2 =36, p<0.001 |

| Extra Help | 74 (35) | 63 (68) | χ2 =27.5, p<0.001 |

| IQ | 108.7 ± 14.8 | 99.7 ± 14.3 | t=4.8, p<0.0001 |

| GAF | 59.9 ± 9.3 | 41.3 ± 7.6 | t=17, p<0.0001 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Bipolar Disorders | 13 (6) | 61 (66) | χ2 =123.2, p<0.001 |

| Multiple Anxiety Disorders | 42 (20) | 55 (59) | χ2 =45.4, p<0.001 |

| ADHD | 33 (16) | 73 (78) | χ2 =111.7, p<0.001 |

| Conduct Disorder | 11 (5) | 49 (53) | χ2 (2)=91.4, p<0.001 |

ADHD=Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Thirty percent of BD subjects and 42% of subjects with CD had SUD. As a result, we now examine the effects of BD and CD as well as other disorders on this association. When we included BD in the above model, all associations remained significant (all p values <0.05). When we added both BD and ADHD in the models, all associations remained significant (all p values <0.05). When we simultaneously included BD, ADHD, CD, multiple anxiety disorders, and gender in the model, the association for any SUD (HR: 2.8; 95% CI: 1.10, 6.9; p=0.03) and alcohol use disorders remained significant (HR: 3.4; 95% CI: 1.1, 10.5; p=0.03); all others lost significance (all p values >0.05). Further, when we only included CD in the original model, the association for any SUD remained significant (HR: 2.7; 95% CI:1.1, 6.7; p=0.03) while all other associations lost significance (all p values >0.05).

3.4 CBCL AAA Scores among individuals with SUD and cigarette smoking

We then investigated if there was evidence of DESR among subjects with SUD. Overall, we found a significant difference in the cumulative CBCL AAA scores of subjects with SUD compared to those without any SUD (196 ± 26.8 vs 170 ± 25.9; t = −5.7; p<0.0001). Specifically, we found that subjects with any SUD had higher scores on the scales for aggression (beta: 9.9; 95% CI: 6.5, 13.4; p<0.001), attention (beta: 7.5; 95% CI: 4.1, 10.7; p<0.001), and anxious-depressed (beta: 6.6; 95% CI: 3.2, 9.9; p<0.001). We found similar results for alcohol use disorders, drug use disorders, cigarette smoking, and the combination of alcohol plus drug use disorders. Subjects with these SUD had higher scores on all of the CBCL AAA scores compared to subjects without these disorders (p<0.01).

3.5 Combined Drug and Alcohol Use Disorders and DESR

Subjects with DESR (10% (N=5); OR: 5.6; 95% CI: 1.7, 18.0; p=0.004) as well as subjects with higher scores (>2SD; 16% (N=7); OR: 6.9; 95% CI: 2.3, 21.4; p=0.001) on the CBCL were 5-7 times more likely to have a combined drug plus alcohol use disorder compared to subjects without DESR (2% (N=5). We found no significant difference in SUD severity among the groups of subjects with DESR (1SD vs. 2SD; OR: 1.2; 95% CI: 0.4, 3.6; p=0.7). When BD was added to the model, the association lost significance (all p values > 0.05). In regards to severe vs. moderate impairment related to the subject’s SUD, we found no significant differences between subjects with and without DESR or among the groups of subjects with 1SD and 2SD above the mean (all p values > 0.05).

3.6 SUD onset

We found that subjects with DESR compared to without DESR had an almost 2 year earlier onset of a drug use disorder (13.3 ± 1.2 years vs 15 ± 1.7 years; beta: −1.9; 95% CI: −3.2, −0.7; p=0.004) or any SUD (14.1 ± 1.8 years vs. 13 ± 1.2 years; beta: −1.4; 95% CI: −2.6, −0.2; p=0.002). In contrast, we also found that subjects with scores >2 SD above the norm had a later onset of alcohol use compared to subjects with 1 SD above the norm (14.7±2 years vs. 13 ± 1.3 years; beta: 1.7; 95% CI: 0.1, 3.4; p=0.04). We found no other significant findings among the groups (all p values > 0.05).

4. DISCUSSION

The results of our study suggest that DESR is associated with cigarette smoking and SUD in our sample. In our adolescents, those with DESR were found to have higher rates of SUD and earlier-onset SUD relative to those without DESR. Interestingly, severity of DESR was not linked to a differential risk for SUD. While higher rates of DESR were found in adolescents with BD, youth without BD who manifest DESR were also at elevated risk for cigarette smoking and SUD. Conversely, cigarette smoking and SUD was related to higher risk for DESR.

Our findings are similar to other studies showing an association between DESR and cigarette smoking or SUD (Aguilar de Arcos et al., 2008; Cheetham et al., 2010; Dorard et al., 2008; Gonzalez et al., 2008). For instance, studies have shown DESR to be related to motivation and use of cigarettes, (Gonzalez et al., 2008) marijuana, (Bonn-Miller et al., 2008; Cheetham et al., 2010) and opioids (Aguilar de Arcos et al., 2008). While the current results were cross-sectional in nature, longitudinal data has shown that mood dysregulation predicts dysfunction and SUD over almost two decades (Holtmann et al., 2011). Not surprising, longitudinal data in youth also demonstrates that the inability to modulate self-esteem, affect, relationships, or self-care predisposes to later SUD (Newcomb and Bentler, 1988; Shedler and Block, 1990).

DESR appears to be an important contributor to the etiology and maintenance of SUD. As reviewed comprehensively by Cheetham et al. (2010), DESR includes both negative and positive affect as well as effortful control that are connected to SUD. SUD may be related to negative affect as a coping mechanism or avoidance of substance withdrawal (Cheetham et al., 2010; Kassel et al., 2007; Khantzian, 1985). With positive affect, excessive (mania, agitation) or blunted states may drive SUD (Cheetham et al., 2010). Affect is related to motivation and regulation of behavior and cognition, decision-making, and positive and negative reinforcement (Cheetham et al., 2010). Not surprisingly, overlap in brain mechanisms exists between that speculated in addictive disorders and the regulation of mood or affect (Cheetham et al., 2010; DelBello et al., 2004; Koob, 2006).

Interestingly, not only is DESR speculated to be related to the initiation of and risk for SUD, but DESR may also be related to the course and developmental stage of SUD (Cheetham et al., 2010). In our sample, DESR was related to a higher risk and earlier-onset of SUD. In evaluating SUD in the course of BD in adults, SUD is not only connected to DESR (Strakowski et al., 1998), but SUD and BD severity are highly interrelated (Strakowski et al., 2005, 2007). Hence, the marked affective instability and self-regulation deficits seen in pediatric BD may be linked to SUD through internal characteristics. In our sample, for instance, we have found evidence of self-medication of “mood” (e.g., DESR) for SUD (Lorberg et al., 2010). Following the role of DESR, it is not surprising that treatments of SUD often encompass treatment of DESR (Bornovalova and Daughters, 2007; McMain et al., 2001).

The current study was one of the first to examine levels of DESR by proxy of previously delineated cutoffs of 1SD (Althoff et al., 2010b; Biederman et al., 2008) and 2 SD elevation (Althoff et al., 2010a) on subscales of the CBCL. We were surprised to see that there were few differences between those with substantial differences in DESR in the risk for SUD. These data seem to suggest that a threshold exists by which youth are at risk for SUD who have at least 1 SD deviation from the mean on the Aggression, Attention, Anxiety subscales of the CBCL. These data seem to suggest that even a modest amount of clinically significant emotional dysregulation predisposes youth to a high risk for cigarette smoking and SUD.

The clinical implications for this study are that youth with high scores on subscales of the CBCL (Aggression, Attention, Anxiety) may be at very high risk for cigarette smoking and SUD. Given that elevations of these subscales of the CBCL are seen and may be indicative of pediatric BD, ADHD, and conduct disorder (Biederman et al., 2012), youth with these disorders should be screened for DESR that in turn, may place them at risk for cigarette smoking and SUD. It may also be that emotional dysregulation drives SUD; and as such, preventive efforts and early intervention may reduce the ultimate risk and outcome of cigarette smoking and SUD in youth with DESR. For example, psychosocial and pharmacological therapies targeted to DESR in these youth may ultimately reduce the risk for SUD and other impairment.

There are a number of substantial limitations to the current findings. Despite the large sample of subjects in our study, a smaller group had elevated scales on the CBCL indicative of DESR. Our sampling was cross-sectional in nature, and we are unable to assert, for example, that DESR predicts SUD. We used a proxy of DESR that was derived from the CBCL (Biederman et al., 2012) and may not reflect the full spectrum of both positive and negative affective states that have been posited with DESR. Our determination of SUD was by indirect and direct structured interview and not objective measures. However, in other similar samples we have found structured interview data to be more sensitive to SUD than random urine toxicology screen (Gignac et al., 2005). Other psychiatric disorders were associated with DESR and may have confounded our results in so much that they contributed independently to SUD. For example, while we were able to demonstrate significant outcomes for SUD, alcohol use disorders, and specific drug and alcohol use disorders while controlling for comorbid disorders, we had trend findings when adding conduct disorder-an important independent risk factor for SUD (Wilens et al., 2009).

Despite these limitations, our findings highlight that DESR appears to be associated with a higher risk of cigarette smoking and SUD. Future longitudinal studies disentangling the temporal relationship, causal nature, brain neurocircuitry and predictability of DESR and SUD are necessary.

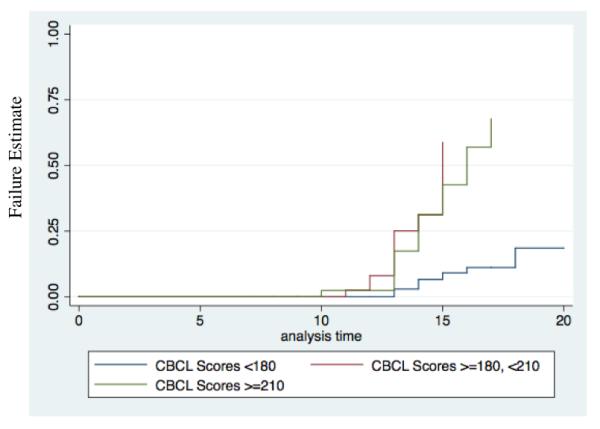

Figure 1. Kaplan Meier Curve of Any Substance Use Disorders (moderate or severe; N=303).

Overall Association: Χ2=30.24, p<0.001. There were significant differences between CBCL scores >=180 and <210 and scores <180 (p<0.001); and between CBCL scores >=210 and scores <180 (p<0.001). No significant difference were found between CBCL scores >=210 and scores >=180, <210 (p=0.6).

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source: Funding for this study was provided by NIH R01 DA12945 (TW) and K24 DA016264 (TW); the NIH had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors: Authors Timothy Wilens and Joseph Biederman designed the study and generated the hypothesis for this manuscript. Authors Rachel Shelley-Abrahamson and Jesse Anderson managed the literature searches and summaries of previous related work. Author MaryKate Martelon, undertook the statistical analysis, and Dr. Timothy E. Wilens wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Timothy Wilens in the past 3 years has received research support from NIH(NIDA) and Shire; and has been a consultant for Euthymics, Lilly and Shire. Dr. Wilens has a published book with Guilford Press: Straight Talk About Psychiatric Medications for Kids

Dr. Joseph Biederman is currently receiving research support from the following sources: Elminda, Janssen, McNeil, and Shire.

In 2011, Dr. Joseph Biederman gave a single unpaid talk for Juste Pharmaceutical Spain, received honoraria from the MGH Psychiatry Academy for a tuition-funded CME course, and received an honorarium for presenting at an international scientific conference on ADHD. He also received an honorarium from Cambridge University Press for a chapter publication. Dr. Biederman received departmental royalties from a copyrighted rating scale used for ADHD diagnoses, paid by Eli Lilly, Shire and AstraZeneca; these royalties are paid to the Department of Psychiatry at MGH.

In 2010, Dr. Joseph Biederman received a speaker’s fee from a single talk given at Fundación Dr.Manuel Camelo A.C. in Monterrey Mexico. Dr. Biederman provided single consultations for Shionogi Pharma Inc. and Cipher Pharmaceuticals Inc.; the honoraria for these consultations were paid to the Department of Psychiatry at the MGH. Dr. Biederman received honoraria from the MGH Psychiatry Academy for a tuition-funded CME course.

In 2009, Dr. Joseph Biederman received a speaker’s fee from the following sources: Fundacion Areces (Spain), Medice Pharmaceuticals (Germany) and the Spanish Child Psychiatry Association.

In previous years, Dr. Joseph Biederman received research support, consultation fees, or speaker’s fees for/from the following additional sources: Abbott, Alza, AstraZeneca, Boston University, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltech, Cephalon, Eli Lilly and Co., Esai, Forest, Glaxo, Gliatech, Hastings Center, Janssen, McNeil, Merck, MMC Pediatric, NARSAD, NIDA, New River, NICHD, NIMH, Novartis, Noven, Neurosearch, Organon, Otsuka, Pfizer, Pharmacia, Phase V Communications, Physicians Academy, The Prechter Foundation, Quantia Communications, Reed Exhibitions, Shire, The Stanley Foundation, UCB Pharma Inc., Veritas, and Wyeth.

All other authors (MaryKate Martelon, Jesse Anderson, and Rachel Shelley-Abrahamson) declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/ 4-18 and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont; Burlington: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar de Arcos F, Verdejo-Garcia A, Ceverino A, Montanez-Pareja M, Lopez-Juarez E, Sanchez-Barrera M, Lopez-Jimenez A, Perez-Garcia M, PEPSA Team Dysregulation of emotional response in current and abstinent heroin users: negative heightening and positive blunting. Psychopharmacol. (Berl.) 2008;198:159–166. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althoff RR, Ayer LA, Rettew DC, Hudziak JJ. Assessment of dysregulated children using the Child Behavior Checklist: a receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. Psychol. Assess. 2010a;22:609–617. doi: 10.1037/a0019699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althoff RR, Verhulst FC, Rettew DC, Hudziak JJ, van der Ende J. Adult outcomes of childhood dysregulation: a 14-year follow-up study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2010b;49:1105–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosini PJ. Historical development and present status of the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children (K-SADS) J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2000;39:49–58. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelson D, Birmaher B, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Iyengar S, Bridge J, Keller M. Phenomenology of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2006;63:1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR, Fischer M. ADHD in Adults: What the Science Says. The Guilford Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Ball SW, Monuteaux MC, Kaiser R, Faraone SV. CBCL clinical scales discriminate ADHD youth with structured-interview derived diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) J. Atten. Disord. 2008;12:76–82. doi: 10.1177/1087054707299404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Wozniak J, Mick E, Kwon A, Cayton GA, Clark SV. Clinical correlates of bipolar disorder in a large, referred sample of children and adolescents. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2005;39:611–622. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Petty CR, Day H, Goldin RL, Spencer T, Faraone SV, Surman CB, Wozniak J. Severity of the aggression/anxiety-depression/attention child behavior checklist profile discriminates between different levels of deficits in emotional regulation in youth with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2012;33:236–243. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182475267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Petty CR, Monuteaux MC, Evans M, Parcell T, Faraone SV, Wozniak J. The Child Behavior Checklist-Pediatric Bipolar Disorder profile predicts a subsequent diagnosis of bipolar disorder and associated impairments in ADHD youth growing up: a longitudinal analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2009;70:732–740. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, Faraone S, Weber W, Curtis S, Thornell A, Pfister K, Jetton JG, Soriano J. Is ADHD a risk for psychoactive substance use disorder? Findings from a four year follow-up study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1997;36:21–29. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199701000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Wozniak J, Kiely K, Ablon S, Faraone S, Mick E, Mundy E, Kraus I. CBCL clinical scales discriminate prepubertal children with structured-interview derived diagnosis of mania from those with ADHD. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1995;34:464–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Zvolensky MJ. Emotional dysregulation: association with coping-oriented marijuana use motives among current marijuana users. Subst. Use Misuse. 2008;43:1653–1665. doi: 10.1080/10826080802241292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Daughters SB. How does dialectical behavior therapy facilitate treatment retention among individuals with comorbid borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders? Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007;27:923–943. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson GA, Bromet EJ, Sievers S. Phenomenology and outcome of subjects with early- and adult-onset psychotic mania. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2000;157:213–219. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham A, Allen NB, Yucel M, Lubman DI. The role of affective dysregulation in drug addiction. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010;30:621–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delbello MP, Hanseman D, Adler CM, Fleck DE, Strakowski SM. Twelve-month outcome of adolescents with bipolar disorder following first hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164:582–590. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.4.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelBello MP, Zimmerman ME, Mills NP, Getz GE, Strakowski SM. Magnetic resonance imaging analysis of amygdala and other subcortical brain regions in adolescents with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:43–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-5618.2003.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorard G, Berthoz S, Phan O, Corcos M, Bungener C. Affect dysregulation in cannabis abusers: a study in adolescents and young adults. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2008;17:274–282. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0663-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findling RL, Gracious BL, McNamara NK, Youngstrom EA, Demeter CA, Branicky LA, Calabrese JR. Rapid, continuous cycling and psychiatric co-morbidity in pediatric bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3:202–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, D.C.: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Tillman R, Bolhofner K, Zimerman B. Child bipolar I disorder: prospective continuity with adult bipolar I disorder; characteristics of second and third episodes; predictors of 8-year outcome. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2008;65:1125–1133. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.10.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Delbello MP, Frazier J, Beringer L. Phenomenology of prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder: examples of elated mood, grandiose behaviors, decreased need for sleep, racing thoughts and hypersexuality. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2002;12:3–9. doi: 10.1089/10445460252943524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gignac M, Wilens TE, Biederman J, Kwon A, Mick E, Swezey A. Assessing cannabis use in adolescents and young adults: what do urine screen and parental report tell you? J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2005;15:742–750. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BI, Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Goldstein TR, Esposito-Smythers C, Strober MA, Hunt J, Leonard H, Gill MK, Iyengar S, Grimm C, Yang M, Ryan ND, Keller MB. Significance of cigarette smoking among youths with bipolar disorder. Am. J. Addict. 2008a;17:364–371. doi: 10.1080/10550490802266151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein BI, Strober MA, Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Esposito-Smythers C, Goldstein TR, Leonard H, Hunt J, Gill MK, Iyengar S, Grimm C, Yang M, Ryan ND, Keller MB. Substance use disorders among adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2008b;10:469–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00584.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A, Zvolensky MJ, Vujanovic AA, Leyro TM, Marshall EC. An evaluation of anxiety sensitivity, emotional dysregulation, and negative affectivity among daily cigarette smokers: relation to smoking motives and barriers to quitting. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2008;43:138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2004;26:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Holtmann M, Buchmann AF, Esser G, Schmidt MH, Banaschewski T, Laucht M. The Child Behavior Checklist-Dysregulation Profile predicts substance use, suicidality, and functional impairment: a longitudinal analysis. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2011;52:139–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Evatt DP, Greenstein JE, Wardle MC, Yates MC, Veilleux JC. The acute effects of nicotine on positive and negative affect in adolescent smokers. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2007;116:543–553. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1985;142:1259–1264. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. The neurobiology of addiction: a neuroadaptational view relevant for diagnosis. Addiction. 2006;101(Suppl. 1):23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowatch RA, Youngstrom EA, Danielyan A, Findling RL. Review and meta-analysis of the phenomenology and clinical characteristics of mania in children and adolescents. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:483–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibenluft E, Charney DS, Pine DS. Researching the pathophysiology of pediatric bipolar disorder. Bio. Psychiatry. 2003;53:1009–1020. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibenluft E, Rich BA, Vinton DT, Nelson EE, Fromm SJ, Berghorst LH, Joshi P, Robb A, Schachar RJ, Dickstein DP, McClure EB, Pine DS. Neural circuitry engaged during unsuccessful motor inhibition in pediatric bipolar disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164:52–60. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.A52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorberg B, Wilens TE, Martelon M, Wong P, Parcell T. Reasons for substance use among adolescents with bipolar disorder. Am. J. Addict. 2010;19:474–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClellan J, Kowatch R, Findling RL. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2007;46:107–125. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000242240.69678.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMain S, Korman LM, Dimeff L. Dialectical behavior therapy and the treatment of emotion dysregulation. J. Clin. Psychol. 2001;57:183–196. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(200102)57:2<183::aid-jclp5>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2010;49:980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Impact of adolescent drug use and social support on problems of young adults: a longitudinal study. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1988;97:64–75. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimherr F, Marchant BK, Strong RE, Hedges DW, Adler L, Spencer TJ, West SA, Soni P. Emotional dysregulation in adult ADHD and response to atomoxetine. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;58:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shedler J, Block J. Adolescent drug use and psychological health: a longitudinal inquiry. Am. Psychol. 1990;45:612–630. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski S, Sax K, McElroy S, Keck P, Hawkins J, West S. Course of psychiatric and substance abuse syndromes co-occurring with bipolar disorder after a first psychiatric hospitalization. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1998;59:465–471. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski SM, DelBello MP, Fleck DE, Adler CM, Anthenelli RM, Keck PE, Jr., Arnold LM, Amicone J. Effects of co-occurring alcohol abuse on the course of bipolar disorder following a first hospitalization for mania. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2005;62:851–858. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.8.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski SM, DelBello MP, Fleck DE, Adler CM, Anthenelli RM, Keck PE, Jr., Arnold LM, Amicone J. Effects of co-occurring cannabis use disorders on the course of bipolar disorder after a first hospitalization for mania. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2007;64:57–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strober M, Carlson G. Predictors of bipolar illness in adolescents with major depression: a follow-up investigation. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1982;10:299–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surman C, Biederman J, Spencer T, Miller CA, Faraone SV. Understanding Deficient Emotional Self Regulation in Adults with Attention Deficity Hyperactivity Disorder: A Controlled Study. Paper presented at the AACAP; New York, NY. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg NZ, Glantz MD. Child psychopathology risk factors for drug abuse: overview. J. Clin. Child Psychology. 1999;28:290–297. doi: 10.1207/S15374424jccp280301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West SA, Strakowski SM, Sax KW, McElroy SL, Keck PE, McConville BJ. Phenomenology and comorbidity of adolescents hospitalized for the treatment of acute mania. Biol. Psychiatry. 1996;39:458–460. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00525-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Biederman J, Abrantes AM, Spencer TJ. Clinical characteristics of psychiatrically referred adolescent outpatients with substance use disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 1997;36:941–947. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Biederman J, Adamson JJ, Henin A, Sgambati S, Gignac M, Sawtelle R, Santry A, Monuteaux MC. Further evidence of an association between adolescent bipolar disorder with smoking and substance use disorders: a controlled study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;95:188–198. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Martelon M, Kruesi MJ, Parcell T, Westerberg D, Schillinger M, Gignac M, Biederman J. Does conduct disorder mediate the development of substance use disorders in adolescents with bipolar disorder? A case-control family study. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2009;70:259–265. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, DuHamel K, Vaccaro D. Activity and mood temperament as predictors of adolescent substance use: test of a self-regulation mediational model. J. Person. Soc. Psychol. 1995;68:901–916. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.5.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young S, Mikulick S, Goodwin M, Hardy J, Martin C, Zoccolillo M, Crowley T. Treated delinquent boys’ substance use: onset, pattern, relationship to conduct and mood disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;37:149–162. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)01069-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]