Abstract

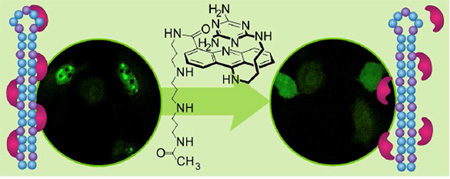

Myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1) is caused by an expanded CUG repeat (CUGexp) that sequesters muscleblind-like 1 protein (MBNL1), a protein that regulates alternative splicing. CUGexp RNA is a validated drug target for this currently untreatable disease. Herein, we develop a bioactive small molecule (1) that targets CUGexp RNA and is able to inhibit the CUGexp·MBNL1 interaction in cells that model DM1. The core of this small molecule is based on ligand 2, which was previously reported to be active in an in vitro assay. A polyamine-derivative side chain was conjugated to this core to make it aqueous-soluble and cell penetrable. In a DM1 cell model this conjugate was found to disperse CUGexp ribonuclear foci, release MBNL1, and partially reverse the mis-splicing of the insulin receptor pre-mRNA. Direct evidence for ribonuclear foci dispersion by this ligand was obtained in a live DM1 cell model using time-lapse confocal microscopy.

RNA is an important, yet underutilized, drug target. To date, the most common RNA drug targets have been ribosomal RNA and HIV RNA.1–3 With recent structural and functional discoveries, non-coding RNA is gradually becoming an attractive drug target4–6 and much is now known about designing ligands to interact with RNA.7–9 Myotonic dystrophy (dystrophia myotonica, DM) is among the pathologies where RNA stands as the most appropriate target for drug discovery.10 DM is the most common adult muscular dystrophy with a prevalence of 1:8,000 to 1:20,000 worldwide.11 Currently there is no treatment for DM, only palliative therapy.12

Myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1), originates from the progressive expansion of CTG repeats in the 3’-untranslated region of the DMPK gene. Thus, expanded CUG repeat transcripts (CUGexp) are the known causative agent of DM1.13,14 The CUGexp RNA manifests its toxicity through a gain-of-function mechanism involving the sequestration of all three paralogs of human MBNL including MBNL1, a key regulatory protein of alternative splicing.15–17 The MBNL1·CUGexp aggregate forms ribonuclear foci, a hallmark of DM1 cells.18 In a mouse model of DM1, a morpholino antisense oligonucleotide (ASO),19 2’-O-(2-methoxyethyl) ASO,20 and D-amino acid hexapeptide, each targeting CUGexp, rescued the mis-splicing and reversed the phenotype.21 These studies validated CUGexp as a drug target and greatly increased interest in finding small molecules that function similarly. Pentamidine,22 benzo[g]quinolone-based heterocycles,23 a Hoechst derivative (H1),24 a modularly assembled Hoechst 33258,25,26 and ligand 2, reported by our laboratory,27 are examples of bioactive CUG repeat binders at various stages of development as potential therapeutic agents for DM1.

Our previously reported approach, which led to ligand 2 as a binder of CUG, was based on the notion that selectivity was paramount and could be achieved by rational design focusing on recognition of the UU mismatch in double stranded CUGexp.26 We found that the triaminotriazine ring (recognition unit) has a key role in the inhibition of (CUG)12·MBNL1 interaction as several acridine derivatives that lacked this unit showed no inhibition potency in our in an in vitro assay (Arambula, J. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Illinois, 2008). Although 2 proved to be among the most selective and effective inhibitors of the (CUG)12·MBNL1 interaction, despite its in vitro activity, it was not active in a cellular model of DM1. Its drugability was limited both because of its low water solubility and its inability to penetrate the cellular membrane. Herein we report further development of this small molecule into an active ligand in vivo through its conjugation to a cationic polyamine and the first observation using time-lapse confocal microscopy of foci dispersion in live cells that model DM1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

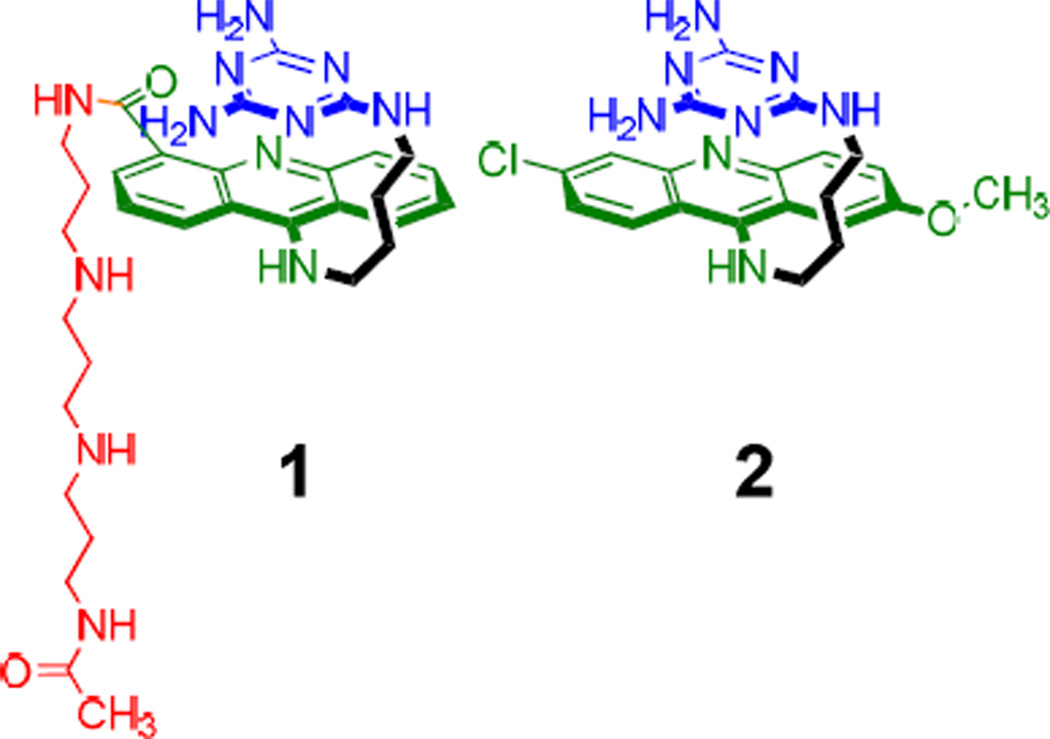

Ligand 1 (Figure 1) is a conjugate of the previously reported in vitro active ligand 2 (Figure 1) and N-[3-({3-[(3-aminopropyl)amino]propyl}amino)propyl] acetamide side chain. The synthesis scheme of 1 is shown in Supplementary Figure 3. The choice of the side chain was guided by four objectives: (1) increasing its aqueous solubility, (2) increasing its affinity to RNA through electrostatic interactions with the phosphate backbone,28 (3) not adding to its cytotoxicity, and most importantly, (4) making it cell as well as nucleus penetrable. In fact, polyamine compounds are essential for cell growth and are easily transported across cellular membranes via the polyamine transporting system (PTS).29 We were encouraged by the fact that previously reported acridine-polyamine conjugates were recognized by the PTS for cellular uptake.30,31 These conjugates also exhibited increased activity for nucleic acids.32

Figure 1.

Structures of 1 and 2

Stability of Model CUGexp and Effect of Ligand 1

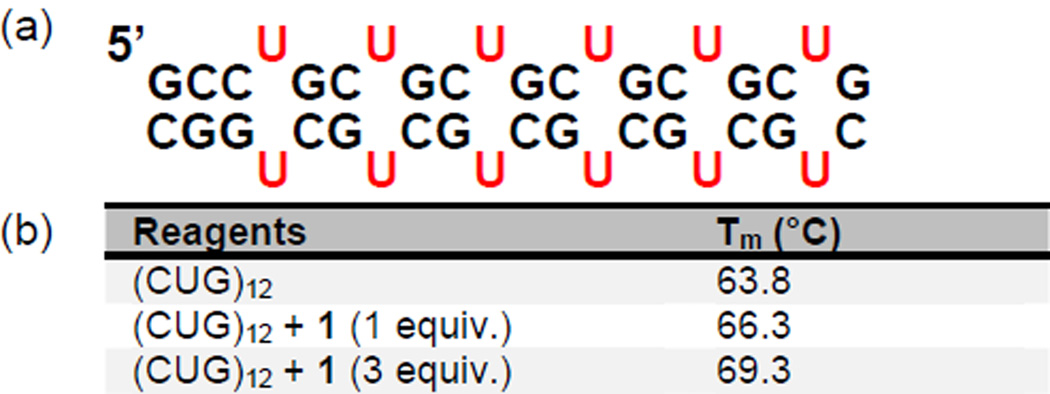

The binding of 1 to a model of CUGexp was studied by UV melting experiments. Thus, a thermal denaturation study of (CUG)12, a validated model of CUGexp,33 was carried out in the presence of one and three equivalents of ligand 1 (Figure 2a); simple monophasic melting curves with a ΔTm of 2.5 °C and 5.5 °C were observed, respectively (Figure 2b and Supplementary Figure 10). This finding indicates binding of 1 to (CUG)12 and stabilization of the double stranded (ds) (CUG)12 hairpin. The latter finding is important because it has been proposed that MBNL1 displays a preference for single stranded (ss) RNA.34, 35 If this model is correct, any ligand that stabilizes the ds form of CUGexp may prove to be a more effective inhibitor of the (CUG)12·MBNL1 interaction. Thus, the observed stabilization of the ds form of (CUG)12 was an encouraging result, although not sufficient to ensure selective and effective inhibition of (CUG)12·MBNL1 interaction.

Figure 2.

Ligand 1 stabilizes the ds form of (CUG)12. a) Schematic representation of (CUG)12. b) Tm of (CUG)12 hairpin in the presence of 1 and 3 equivalents of 1 in 1X PBS buffer. Values were measured in duplicate or triplicate with repeats agreeing within 1%.

Inhibition of (CUG)12·MBNL1 Interaction by 1

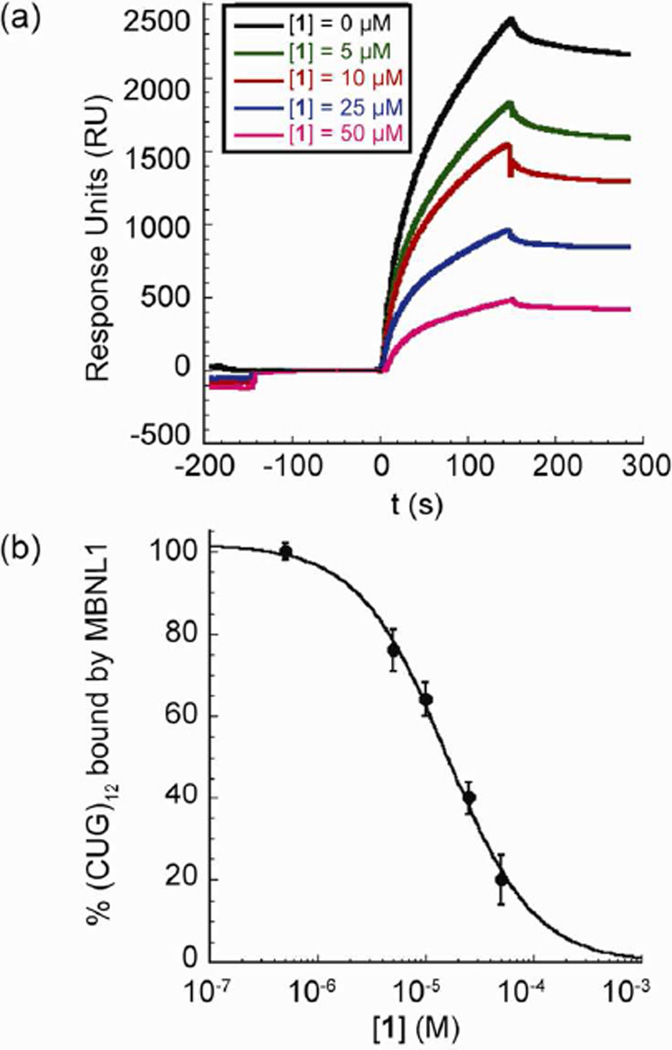

To our knowledge, SPR has not previously been used to characterize the MBNL1·CUG interaction or its inhibition by small molecules.23,36 Because the technique is particularly well suited for quantifying the binding of proteins to a target on the SPR chip, we developed a simple SPR-based method to directly measure MBNL1 complexation of (CUG)12 in real time under equilibrium conditions and in a label-free format. Further, we were able to quantify the inhibition potency of 1 and its selectivity. The selectivity was assessed by performing the assay in the presence of a large excess of competitor tRNA.

Thus, biotinylated (CUG)12 was immobilized on a streptavidin coated SPR sensor chip and incubated with different concentrations of 1 to reach a steady state response (response units, RU, see Figure 3a) over 150 s. The response to the binding of 1 was negligible in comparison to protein binding so the direct contribution of 1 could be ignored. Successive injections of a 0.65 µM solution of MBNL1 containing the same concentration of 1 as in the pre-incubation, led to varying responses depending on the concentration of 1. Because the SPR signal directly reflects the binding of MBNL1 to the biotinylated (CUG)12, the differences in the response curves are a direct result of inhibition by 1.

Figure 3.

Ligand 1 inhibits MBNL1·(CUG)12 complex. a) Representative sensograms from SPR studies. Biotinylated (CUG)12 is immobilized on the streptavidin coated sensor chip. Ligand 1 is injected from t = −150 s to t = 150 s. GST-MBNL1, 0.65 µM, is injected from t = 0 s to t = 150 s. Baseline for the curves was set to RU = 0 at t = 0. b) Fitting data to a dose-response curve indicates inhibition of the (CUG)12·MBNL1 interaction in the presence of varying concentrations of 1. Error bars represent mean ± s.d. of three replicates.

The curves recorded in the presence and absence of 580 µM yeast tRNA were identical, indicating selective inhibition by 1. All of the data shown herein were from runs in the presence of tRNA. The maximum RU at 150 s was recorded for each concentration of 1 and converted to the fraction of (CUG)12 bound by MBNL1, all values normalized to that measured in the absence of 1. Fitting the data points in the plot of % (CUG)12 bound by MBNL1 versus increasing concentrations of 1 (Figure 3b) gave an apparent IC50 value of 15 ± 2 µM.

These in vitro experiments demonstrate that 1 binds to (CUG)12, stabilizing the hairpin structure and inhibiting (CUG)12·MBNL1 interaction selectively. It is noteworthy that all of the in vitro experiments above were carried out with (CUG)12 in 1X PBS buffer. This particular buffer was chosen because it is the closest of common buffers to physiological conditions. It is also a more challenging buffer for small molecule inhibitors because it increases the (CUG)12·MBNL1 stability, as we obtained a KD value of 5.2 ± 2.5 nM for (CUG)12·MBNL1 interaction in this buffer by SPR technique whereas using EMSA we and others had reported KD values of 26 and 170 nM, respectively.27,33

Bioactivity in DM1 Cell Model

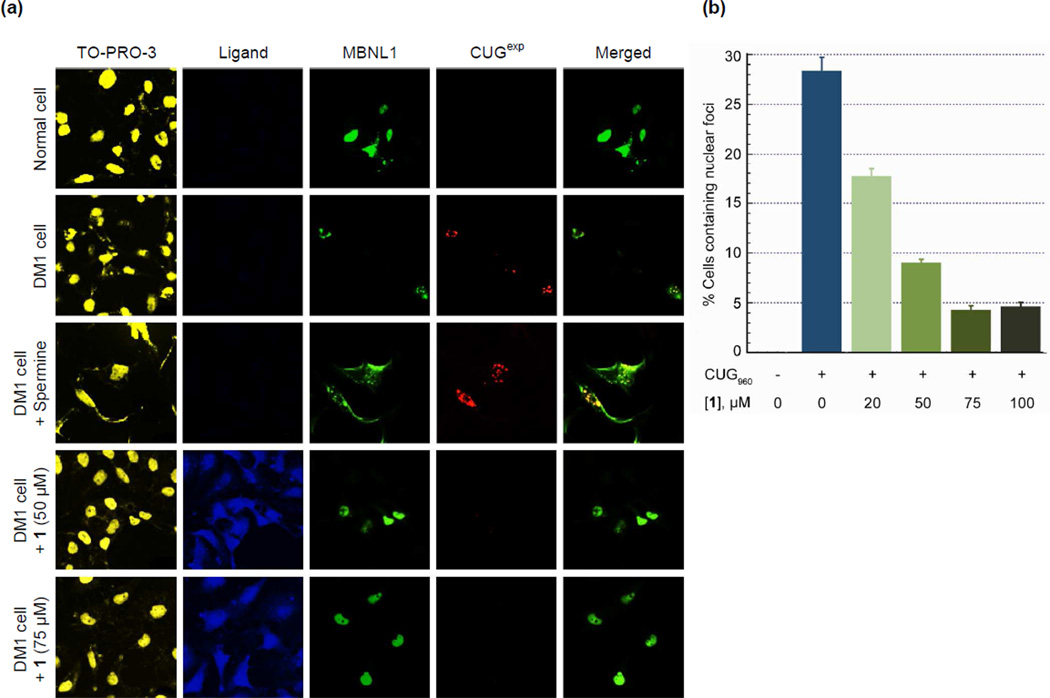

It is a characteristic of DM1 cells that MBNL1 aggregates with CUGexp in nuclear foci.37 To visualize the effect of 1 on these ribonuclear foci, we used confocal microscopy. This was accomplished using a model for a DM1 cell. Thus, HeLa cells were transfected with two plasmids, truncated DMPK-CUG960 and GFP-MBNL1.38 As a negative control, HeLa cells were transfected with truncated DMPK-CUG0 (i.e., no CUG repeat) and GFP-MBNL1 plasmids.38 To detect (CUG)960 foci, Cy3-(CAG)10 was used as a fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) probe. TO-PRO-3 was used to stain the nucleus, this particular dye was chosen because it has no overlap with the other three fluorophores in our system, i.e., the acridine ring of 1, the GFP of GFP-MBNL1 and the Cy3 of the FISH probe. By taking advantage of the acridine fluorescence, the penetration of 1 to the cytoplasm as well as nucleus is tracked in the ligand-treated cells.

Representative images from the confocal microscopy are shown in Figure 4. The negative control cells lacking the (CUG)960 sequence showed no foci but rather MBNL1 dispersed throughout the nucleus (Figure 4a, row 1). However, co-localized MBNL1 and (CUG)960 foci were observed in the DM1 cell model (Fig 4a, row 2). Thus, in the untreated DM1 cells the merged GFP-MBNL1 (green fluorescence) and Cy3-(CAG)10 (red fluorescence) images, showed yellow spots that correspond to MBNL1 and (CUG)960 co-localization in nuclear foci (last column Fig. 4). Likewise, incubation of the DM1 cell model with a negative control compound, 50 µM spermine for 48 h had no effect on the foci (Figure 4a, row 3). However, incubation with 1, at 50 and 75 µM caused almost complete disappearance of the (CUG)960 foci and dispersion of the MBNL1 fluorescence (Figure 4a, rows 4 and 5, respectively). The foci disruption is observed as a disappearance, rather than dispersion of the FISH probe, because it is an exogenous antisense nucleic acid probe only visible when concentrated by a high-localized concentration of CUGexp RNA.39 Cells were classified as having or not having foci. The fraction of cells with (CUG)960 foci was reduced by ca. 86% with 1 at 75 µM with a two-tailed p-value of 0.004 (Figure 4b). Similar responses are seen at 50 and 100 µM ligand.

Figure 4.

Ligand 1 disrupts nuclear foci in fixed DM1 cell model. a) Columns 1–4 as labeled. Column 5 is merge of columns 3 and 4. Confocal fluorescent images show MBNL1 and CUGexp foci are present in row 2 where no ligand is added as well as row 3 where spermine (50 µM), as a negative control compound, is added. CUGexp foci are not visible and MBNL1 is dispersed across the nucleus in negative control cells, row 1, as well as rows 4 and 5 where DM1 cell model is treated with 1 at 50 and 75 µM, respectively, for 48 h. Each box shows a 150 µm × 150 µm area. b) Plot of CUGexp foci-containing cell fraction at various concentrations of 1. These data are gathered from scoring over 100 cells. The error bars represent mean ± standard error of at least three independent experiments. A magnified CUG960 transfected HeLa cell (DM1 cell model) showing ribonuclear foci is shown in Supplementary Figure 12.

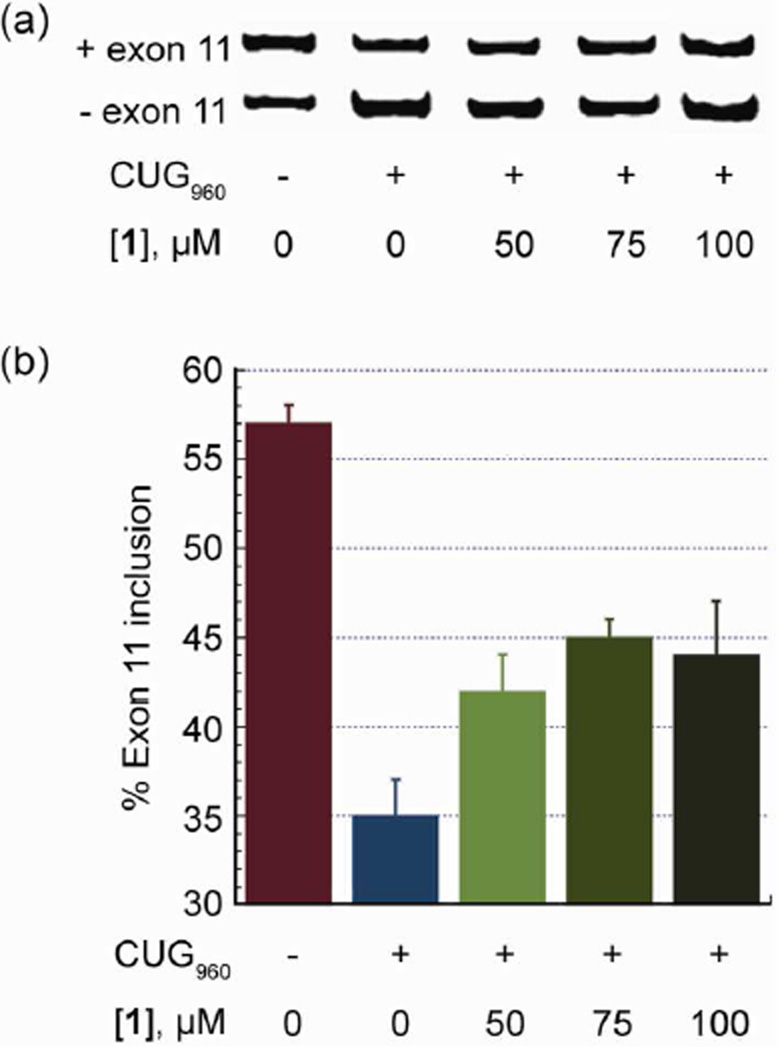

Improvement of Pre-mRNA Mis-Splicing by 1

After confirming that 1 disperses the MBNL1 foci, we sought to study the alternative splicing as a downstream measure of recovered MBNL1 regulatory activity. MBNL1 is known to be a key regulatory protein in alternative splicing and affecting many pre-mRNAs, including the insulin receptor (IR).40 The mis-splicing of IR in DM1 cells occurs with a predominance of isoform A (with exon 11 exclusion) relative to isoform B (with exon 11 inclusion).41 As described above, truncated DMPK mRNAs containing (CUG)960 or no CUG repeats were expressed in HeLa cells to serve as our DM1 cell model and negative control cell, respectively. These cells were co-transfected with an IR mini-gene to study the regulation of splicing of IR by measuring the relative amounts of its two isoforms. Looking at the transcripts in the DM1 cell model showed mis-splicing of IR with 35 ± 2 % isoform B (IR-B), whereas 57 ± 1 % of IR-B, measured in the negative control cell, was considered the baseline exon inclusion. Treatment of the DM1 cell model with a negative control compound, 50 µM spermine, had no effect on the IR mis-splicing (Supplementary Figure 9). The splicing assay was repeated with different concentrations of 1 to see if it was capable of rescuing the mis-splicing of IR, i.e. increasing the fraction of IR-B (Figure 5a).42 Thus, the DM1 model cells were treated with 1 at 50, 75 or 150 µM for 48 h. A rescue of 40% for the IR splicing defect was observed at 75 µM with 45 ± 1% IR-B measured; two-tailed p-values of 0.002 (Figure 5b). Similar responses are seen at 50 and 150 µM ligand. A more quantitative approach would be needed to demonstrate a dose response. It is noteworthy that cytotoxicity of 1 was evaluated by sulforhodamine B assay and less than 10% HeLa cell death was observed at the highest tested concentration (100 µM) after 24 h (Supplementary Figure 11).

Figure 5.

Ligand 1 improves mis-splicing of IR in DM1 cell model. a) A representative gel image of IR alternative splicing. Two bands corresponding to IR isoforms A (+ exon 11) and B (− exon 11), respectively, are derived by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). DM1 cell model is treated with 1 at 50, 75 and 150 µM. b) A plot of the corresponding data shows 40% rescue of mis-splicing at [1] = 75 µM. The error bars represent mean ± standard error of 4–6 independent measurements.

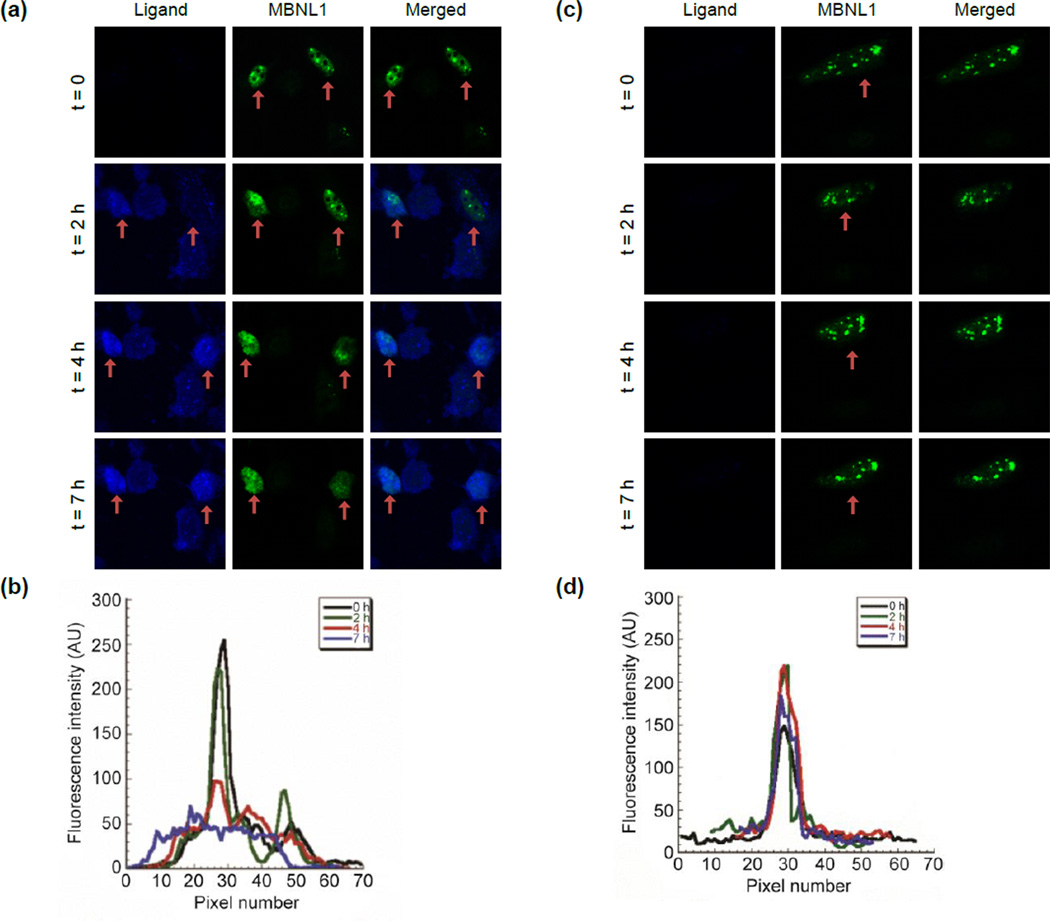

MBNL1 Foci Dispersion in Live Cells by 1

Although the reduction in the foci-containing fixed cells was statistically significant, that experiment represents an indirect measurement of the foci dispersion; because with fixed-cell microscopy, we are not following the same cell directly over time to observe the dispersion of ribonuclear foci upon addition of 1. Thus, to further confirm our observation, we sought to investigate the effect of 1 in a live cell, by time-lapse confocal microscopy.

To monitor drug uptake and foci dispersion in real time, model DM1 cells were incubated with 1 at 75 µM and individual live cells were monitored by confocal microscopy at several time points. The first observation at time point, t = 0, was made immediately before addition of 1 and MBNL1 nuclear foci were clearly present (Figure 6a, t = 0). We found it necessary to use a Petri dish with an imprinted 500 µm grid to relocate the cell following the incubation interval.

Figure 6.

Live cell microscopy demonstrates a direct evidence for MBNL1 foci dispersion with 1. a) Live DM1 model cells are treated with 1 (75 µM) at t = 0, immediately after the first image is taken. Fluoresence of 1, confirms its penetration to the nucleus. MBNL1 nuclear foci are gradually dispersing over time in two cells. Each box shows a 100 µm × 100 µm area. b) Plot of fluorescence intensity of a representative GFP-MBNL1 focus, corresponding to (a), shows dispersion over time. c) A single live cell shows stability of foci in a DM1 cell, in the absence of 1, over the period of 7 h. Each box shows a 100 µm × 100 µm area. d) Plot of fluorescence intensity of a representative GFP-MBNL1 focus, corresponding to (c), shows no dispersion over time.

The ability to monitor the location of 1 was made possible by the inherent fluorescence of the acridine unit. Over time, 1 penetrated the cellular and nuclear membrane and the MBNL1 foci gradually dispersed over the entire nucleus (Figure 6a, t = 2, 4 and 7 h). The intensity of a representative MBNL1 focus (the most intense focus) at these four time points shows this dispersion (Figure 6b). A negative control experiment was performed at the same time points and conditions but without incubation with 1 (Figure 6c). This negative control confirmed the stability of foci over time as the intensity of the GFP-MBNL1 foci was steady (Figure 6d). These results provide direct evidence of the ability of 1 to enter the cell and nucleus and disperse most of the MBNL1·CUG aggregates over a 2–4 h period.

CONCLUSION

Ligand 1 was developed based on a previously reported in vitro active ligand.27 The in vitro activity of 1 was assessed by optical melting and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) techniques. Ligand 1 selectively binds to (CUG)12, stabilizes its hairpin structure and inhibits (CUG)12·MBNL1 interaction. The polyamine side-chain, provides full aqueous solubility that was absent in the initially reported ligand 2. Ligand 1 penetrates the cellular as well as nuclear membrane. The bioactivity of 1 in model DM1 cells was studied by FISH technique using confocal microscopy and it was found to significantly reduce the number of ribonuclear foci. In splicing experiments, 1 partially rescued the IR mis-splicing. Moreover, we studied live DM1 model cells using time-lapse confocal microscopy. For the first time, we were able to observe uptake of a small molecular inhibitor of the (CUG)12·MBNL1 interaction by single live cells and further see its ability to disperse the foci over time. This approach is a powerful way to assess directly the effectiveness of small molecules targeted to CUG repeats. The positive results with compound 1 suggest that it is a good candidate for further development and therefore, toxicity and related studies are underway.

METHODS

MBNL1N, CUG0/960 Plasmid and RNAs

The expression vector pGEX-6p-1/MBNL1N was obtained from Maurice S. Swanson (University of Florida, College of Medicine). Wild type DMPK-CUG960, DMPK-CUG0 and GFP-MBNL1 mini-genes were obtained from the lab of Thomas Cooper (Baylor College of Medicine). The insulin receptor (IR) mini-gene was obtained from the lab of Nicholas Webster (University of California, San Diego).

The MBNL1 used here is MBNL1N containing the four zinc finger motifs of MBNL1 and a hexa His tag (C-terminus). MBNL1N is known to bind RNA with a similar affinity as the full-length MBNL1 and is commonly used in such studies.43 All the oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technology and were HPLC purified. The sequences and modifications for RNA constructs used in this study are as follows:

(CUG)12 construct for optical melting experiments: 5’–GCCUGCUGCUGCUGCUGCUGCUGCUGCUGCUGCUGCUGGC–3’

(CUG)12 construct for SPR experiments: 5’–GCCUGCUGCUGCUGCUGCUGCUGCUGCUGCUGCUGCUGGC-TEG-biotin–3’

MBNL1N Protein Expression and Purification

Using BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RP competent cells (Stratagene), the expression of MBNL1N protein was induced with 1 mM IPTG at OD600 0.6 in LB media with ampicillin for 2 h at 37 °C. Bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation and were then resuspended in a lysis buffer containing 25 mM Tris-Cl (pH = 8), 0.5 M NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 2 mM BME, 5% glycerol, 0.1% Triton X-100, 2 mg mL−1 lysozyme, 0.1 mM PMSF, 1 µM pepstatin, and 1 µM leupeptin, and sonicated six times for 15 s each. The cell pellet was centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected and filtered through a 45 µm Millex filter. To purify MBNL1N, Ni-NTA agarose was incubated with the lysate for 1 h at 4 °C and washed with a washing buffer containing 25 mM Tris-Cl (pH = 8), 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM imidazole and 0.1% Triton X-100, followed by elution with elution buffer of 25 mM Tris-Cl (pH = 8), 0.5 M NaCl, 250 mM imidazole and 0.1% Triton X-100. The eluate containing the GST fusion protein was dialyzed against 1X PBS buffer for using in SPR analysis. The molecular weight was confirmed by MALDI mass spectrometry and the concentration was determined by Bradford assay.

Optical Melting Experiments

The melting temperature of the (CUG)12 was measured on a Shimadzu UV2450 spectrophotometer equipped with a temperature controller. The path length of the cuvettes used was 1 cm. The absorbance of 3.3 µM (CUG)12 in 1X PBS buffer in the absence and presence of 3.3 and 9.9 µM of 1 was recorded at 260 nm with a slit width of 1 nm from 10 °C to 95 °C at a ramp rate of 0.5 °C min−1. Each profile for melting temperature analysis was generated by subtracting the absorbance of the solution of 1 in 1X PBS buffer from the (CUG)12/1 solution. Melting temperatures were determined by fitting the melting curve using Meltwin 3.5 software.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Analysis

All SPR experiments were conducted on a streptavidin coated sensor chip using a Biacore 3000 instrument. Streptavidin coated research grade sensor chips were preconditioned with three consecutive 1-min injections of 1 M NaCl/ 50 mM NaOH before the immobilization was started. 3’-biotin labeled (CUG)12 was captured on flow cell 2 (Response Unit, RU, between 100–1100). Flow cell 1 was used as a reference. Inhibition analysis was carried out in PBS 1X buffer, pH = 7.4, containing 0.05% Tween-20 and 0.2 mg mL−1 (7.4 µM or 580 µM nucleotides) bulk yeast t-RNA to confirm the specificity of inhibition. Various concentrations of 1 were passed over the immobilized RNA at a rate of 20 PL min−1 for 300 s. After the initial 150 s, a solution of GST-MBNL1 protein, 650 nM, in the same buffer was flowed over the surface for 150 s. The reference-subtracted sensograms were obtained by subtracting the measured RU upon injection of PBS buffer from the sensograms. After the dissociation phase, the surface was regenerated, with a pulse of 0.5% SDS and/or 100 mM NaOH, for a few times followed by a buffer wash to reestablish baseline. For inhibition studies, the resulting sensograms were set to the baseline at t = 150 s to offset the binding of 1 to the immobilized (CUG)12 surface. The peak RU at t = 150 s was recorded and converted to the percentage of (CUG)12 bound by MBNL1. All values normalized to that measured in the absence of 1. The data points were fit to a four parameter logistic curve to determine the apparent IC50 using the following equation by Kaleidagraph software:

where Y is the percentage of (CUG)12 bound by MBNL1, Ymax and Ymin are the maximum and minimum of this percentage and n is the Hill coefficient. Two or three separate SPR experiments on different sensor chips with different levels of (CUG)12 immobilization were carried out to verify that the values are not affected by surface RNA density.

FISH (Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization)

A total of ca. 120,000 HeLa cells were seeded in each well of a 6-well plate on coverslips. After a day, the cells were transfected with 500 ng DMPK–CUG0 or DMPK–CUG960 plasmid and 500 ng GFP-MBNL1 plasmid using Lipofectamine following the manufacturer’s protocol at cell confluence of 70–80%.38 After 4 hours, the media was changed and 1 was added to each well at different concentrations (20, 50, 75 and 100 µM). After two days, the cells were fixed with 4% PFA then washed five times with 1X PBS. Fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.5% triton X-100 in 1X PBS at room temperature for 5 min. Cells were prewashed with 30% formamide in 2X SSC for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were probed with FISH probe (1 ng µL−1 of Cy3 CAG10 in 30% formamide, 2X SSC, 2 µg mL−1 BSA, 66 µg mL−1 yeast tRNA) for 2 h at 37 °C. Cells were then washed with 30% formamide in 2X SSC for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by washing with 1X SSC for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were washed twice with 1X PBS and then nuclei were stained with 1 µM To-Pro-3 and washed twice. Cells were mounted onto glass sides with ProLong® Gold. Slides were imaged at RT by LSM 710, AxioObserver confocal microscopy equipment using a confocal single photon technique with a plan-Apochromat 20×/0.8 M27 objective. Image analysis was performed by Axiovision interactive measurement. The following table indicates the excitation filters used in these experiments.

| Fluorophore | Component | Excitation wavelength (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| Acridine | Ligand 1 | 405 |

| GFP | MBNL1 | 488 |

| Cy3 | CUG960 | 555 |

| TO-PRO-3 | Nucleus | 639 |

IR Splicing Assay

A total of ca. 120,000 cells were seeded in each well of a 6-well plate in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 4.5 g L−1 glucose, L-glutamine and no antibiotics. After a day, at about 70–80% confluence, the cells were transfected with 500 ng DMPK–CUG0 or DMPK–CUG960 plasmid and 500 ng IR mini-gene plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 and Opti-MEM reduced serum medium following the standard protocol.38,44 The cells were incubated at 37 °C. After 4 h, the transfection medium was replaced by the DMEM medium and the cells were treated with 1 at three different concentrations (50, 75, and 150 µM).

After 48 h, cells were harvested and total RNA were isolated immediately using total RNA isolation kit and either stored at −80 °C or 1 µg of the RNA processed with reverse transcription step using iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit, the reverse transcription product was cleaned using Quick Spin kit. Approximately 70 ng of cDNA was used in PCR, 31–35 cycles (within a linear range) using PCR Master Mix kit following the standard protocol. The forward primer was 5’-GTA CCA GCT TGA ATG CTG CTC CT, and the reverse primer was 5’-CTC GAG CGT GGG CAC GCT. PCR products were separated on 8% PAGE gel in 1 X TBE, stained with EtBr in 15 min, de-stained with water in 15 min and observed under Molecular Imager.

The gel image was analyzed using ImageJ and the data were plotted using Kaleidagraph. The p-values were calculated using two-tailed Student t test.

Live Cell Imaging

A total of ca. 120,000 HeLa cells were grown in an Ibidi 35 mm Petri dish with a standard bottom, high walls and an imprinted 500 µm relocation grid. After a day, cell confluence reached to about 70–80%, cells were tranfected with 500 ng DMPK–CUG960 plasmid and 500 ng GFP-MBNL1 plasmid using Lipofectamine following standard protocol. After 4 h, media were changed and cells were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2. 24 h post-transfection, ligand 1 was added to final concentration of 75 µM. Live-cell, time-lapse images were taken before addition of 1 as well as at 2, 4 and 7 h time points at RT by a LSM 710, AxioObserver confocal microscopy equipment using a confocal single photon technique with a plan-Apochromat 20×/0.8 M27 objective. Image analysis was performed by Axiovision interactive measurement. For tracking the cells, DIC images were acquired simultaneously with the reflected light images using a TPMT module after setting the Köhler illumination with a fully opened condenser aperture (0.55 NA).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Support of this work by the NIH R01AR058361 (S.C.Z. and A.M.B.) is gratefully acknowledged. The authors would like to thank J. Eichorst and S. Mayandi for their technical help with the confocal microscopy.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Experimental procedures, full characterization data for the compounds, supplementary confocal microscopy and gel images, RNA melting curves and cytotoxicity data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilson WD, Li K. Targeting RNA with small molecules. Curr. Med. Chem. 2000;7:73–98. doi: 10.2174/0929867003375434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearson ND, Prescott CD. RNA as a drug target. Chem. Biol. 1997;4:409–414. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90192-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tor Y. Targeting RNA with small molecules. ChemBioChem. 2003;4:998–1007. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guan L, Disney MD. Recent advances in developing small molecules targeting RNA. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012;7:73–86. doi: 10.1021/cb200447r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas JR, Hergenrother PJ. Targeting RNA with small molecules. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:1171–1224. doi: 10.1021/cr0681546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallego J, Varani G. Targeting RNA with small-molecule drugs: therapeutic promise and chemical challenges. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001;34:836–843. doi: 10.1021/ar000118k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fulle S, Gohlke H. Molecular recognition of RNA: challenges for modelling interactions and plasticity. Journal of molecular recognition : JMR. 2010;23:220–231. doi: 10.1002/jmr.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chow CS, Bogdan FM. A Structural Basis for RNAminus signLigand Interactions. Chem. Rev. 1997;97:1489–1514. doi: 10.1021/cr960415w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlson CB, Stephens OM, Beal PA. Recognition of double-stranded RNA by proteins and small molecules. Biopolymers. 2003;70:86–102. doi: 10.1002/bip.10413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper TA, Wan L, Dreyfuss G. RNA and disease. Cell. 2009;136:777–793. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper TA. A reversal of misfortune for myotonic dystrophy? New Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:1825–1827. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr064708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foff EP, Mahadevan MS. Therapeutics development in myotonic dystrophy type 1. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44:160–169. doi: 10.1002/mus.22090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomes-Pereira M, Cooper TA, Gourdon G. Myotonic dystrophy mouse models: towards rational therapy development. Trends Mol. Med. 2011;17:506–517. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mirkin SM. Expandable DNA repeats and human disease. Nature. 2007;447:932–940. doi: 10.1038/nature05977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Rourke JR, Swanson MS. Mechanisms of RNA-mediated disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:7419–7423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800025200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanadia RN, Shin J, Yuan Y, Beattie SG, Wheeler TM, Thornton CA, Swanson MS. Reversal of RNA missplicing and myotonia after muscleblind overexpression in a mouse poly(CUG) model for myotonic dystrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:11748–11753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604970103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grammatikakis I, Goo YH, Echeverria GV, Cooper TA. Identification of MBNL1 and MBNL3 domains required for splicing activation and repression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:2769–2780. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wheeler TM, Krym MC, Thornton CA. Ribonuclear foci at the neuromuscular junction in myotonic dystrophy type 1. Neuromuscul Disord. 2007;17:242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wheeler TM, Sobczak K, Lueck JD, Osborne RJ, Lin X, Dirksen RT, Thornton CA. Reversal of RNA dominance by displacement of protein sequestered on triplet repeat RNA. Science. 2009;325:336–339. doi: 10.1126/science.1173110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wheeler TM, Leger AJ, Pandey SK, MacLeod AR, Nakamori M, Cheng SH, Wentworth BM, Bennett CF, Thornton CA. Targeting nuclear RNA for in vivo correction of myotonic dystrophy. Nature. 2012;488:111–115. doi: 10.1038/nature11362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia-Lopez A, Llamusi B, Orzaez M, Perez-Paya E, Artero RD. In vivo discovery of a peptide that prevents CUG-RNA hairpin formation and reverses RNA toxicity in myotonic dystrophy models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:11866–11871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018213108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warf MB, Nakamori M, Matthys CM, Thornton CA, Berglund JA. Pentamidine reverses the splicing defects associated with myotonic dystrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:18551–18556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903234106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ofori LO, Hoskins J, Nakamori M, Thornton CA, Miller BL. From dynamic combinatorial 'hit' to lead: in vitro and in vivo activity of compounds targeting the pathogenic RNAs that cause myotonic dystrophy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:6380–6390. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parkesh R, Childs-Disney JL, Nakamori M, Kumar A, Wang E, Wang T, Hoskins J, Tran T, Housman D, Thornton CA, Disney MD. Design of a bioactive small molecule that targets the myotonic dystrophy type 1 RNA via an RNA motif-ligand database and chemical similarity searching. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:4731–4742. doi: 10.1021/ja210088v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pushechnikov A, Lee MM, Childs-Disney JL, Sobczak K, French JM, Thornton CA, Disney MD. Rational design of ligands targeting triplet repeating transcripts that cause RNA dominant disease: application to myotonic muscular dystrophy type 1 and spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9767–9779. doi: 10.1021/ja9020149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Childs-Disney JL, Hoskins J, Rzuczek SG, Thornton CA, Disney MD. Rationally designed small molecules targeting the RNA that causes myotonic dystrophy type 1 are potently bioactive. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012;7:856–862. doi: 10.1021/cb200408a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arambula JF, Ramisetty SR, Baranger AM, Zimmerman SC. A simple ligand that selectively targets CUG trinucleotide repeats and inhibits MBNL protein binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:16068–16073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901824106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischer W, Brissault B, Prevost S, Kopaczynska M, Andreou I, Janosch A, Gradzielski M, Haag R. Synthesis of linear polyamines with different amine spacings and their ability to form dsDNA/siRNA complexes suitable for transfection. Macromol. Biosci. 2010;10:1073–1083. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmer AJ, Wallace HM. The polyamine transport system as a target for anticancer drug development. Amino Acids. 2010;38:415–422. doi: 10.1007/s00726-009-0400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delcros JG, Tomasi S, Carrington S, Martin B, Renault J, Blagbrough IS, Uriac P. Effect of spermine conjugation on the cytotoxicity and cellular transport of acridine. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:5098–5111. doi: 10.1021/jm020843w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanchez-Carrasco S, Delcros JG, Moya-Garcia AA, Sanchez-Jimenez F, Ramirez FJ. Study by optical spectroscopy and molecular dynamics of the interaction of acridine-spermine conjugate with DNA. Biophys. Chem. 2008;133:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez-Flores L, Ruiz-Chica AJ, Delcros JG, Sanchez-Jimenez FM, Ramirez FJ. Effect of spermine conjugation on the interaction of acridine with alternating purine-pyrimidine oligodeoxyribonucleotides studied by CD, fluorescence and absorption spectroscopies. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2008;69:1089–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warf MB, Berglund JA. MBNL binds similar RNA structures in the CUG repeats of myotonic dystrophy and its pre-mRNA substrate cardiac troponin T. RNA. 2007;13:2238–2251. doi: 10.1261/rna.610607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu Y, Ramisetty SR, Hussain N, Baranger AM. MBNL1-RNA recognition: contributions of MBNL1 sequence and RNA conformation. ChemBioChem. 2012;13:112–119. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laurent FX, Sureau A, Klein AF, Trouslard F, Gasnier E, Furling D, Marie J. New function for the RNA helicase p68/DDX5 as a modifier of MBNL1 activity on expanded CUG repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:3159–3171. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mann Da, Kanai M, Maly DJ, Kiessling LL. Probing Low Affinity and Multivalent Interactions with Surface Plasmon Resonance: Ligands for Concanavalin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:10575–10582. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Echeverria GV, Cooper TA. RNA-binding proteins in microsatellite expansion disorders: mediators of RNA toxicity. Brain Res. 2012;1462:100–111. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ho TH, Savkur RS, Poulos MG, Mancini MA, Swanson MS, Cooper TA. Colocalization of muscleblind with RNA foci is separable from mis-regulation of alternative splicing in myotonic dystrophy. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:2923–2933. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Long RM, Elliott DJ, Stutz F, Rosbash M, Singer RH. Spatial consequences of defective processing of specific yeast mRNAs revealed by fluorescent in situ hybridization. RNA. 1995;1:1071–1078. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sen S, Talukdar I, Liu Y, Tam J, Reddy S, Webster NJ. Muscleblind-like 1 (Mbnl1) promotes insulin receptor exon 11 inclusion via binding to a downstream evolutionarily conserved intronic enhancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:25426–25437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.095224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Savkur RS, Philips AV, Cooper TA. Aberrant regulation of insulin receptor alternative splicing is associated with insulin resistance in myotonic dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 2001;29:40–47. doi: 10.1038/ng704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kosaki A, Nelson J, Webster NJ. Identification of intron and exon sequences involved in alternative splicing of insulin receptor pre-mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:10331–10337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuan Y, Compton SA, Sobczak K, Stenberg MG, Thornton CA, Griffith JD, Swanson MS. Muscleblind-like 1 interacts with RNA hairpins in splicing target and pathogenic RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:5474–5486. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kosaki a, Nelson J, Webster NJ. Identification of intron and exon sequences involved in alternative splicing of insulin receptor pre-mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:10331–10337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.