Abstract

The present study includes the molecular characteristics of Trichoderma pleurotum and Trichoderma pleuroticola isolates collected from green moulded cereal straw substrates at 47 oyster mushroom farms in Poland. The screening of the 80 Trichoderma isolates was performed by morphological observation and by using the multiplex PCR assay. This approach enabled specific detection of 47 strains of T. pleurotum and 2 strains of T. pleuroticola. Initial identifications were confirmed by sequencing the fragment of internal transcribed spacer regions 1 and 2 (ITS1 and ITS2) of the rRNA gene cluster and the fragment including the fourth and fifth introns and the last long exon of the translation–elongation factor 1-alpha (tef1) gene. ITS and tef1 sequence information was also used to establish the intra- and interspecies relationship of T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola originating from the oyster mushroom farms in Poland and from other countries. Comparative analysis of the ITS sequences showed that all T. pleurotum isolates from Poland represent one haplotype, identical to that of T. pleurotum strains from Hungary and Romania. Sequence analysis of the tef1 locus revealed two haplotypes (“T” and “N”) of Polish T. pleurotum isolates. The “T” type isolates of T. pleurotum were identical to those of strains from Hungary and Romania. The “N” type isolates possessed a unique tef1 allele. Detailed analysis of the ITS and tef1 sequences of two T. pleuroticola isolates showed their identicalness to Italian strain C.P.K. 1540.

Introduction

Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.) P. Kumm. is one of the most important commercial crop edible mushrooms in Poland. Together with Italy and Hungary, Poland is the main producer of P. ostreatus in Europe. However, significant disintegration of oyster mushroom production and differences in cultivation conditions affect the appearance of many pests and diseases. In recent years, severe symptoms of green mould have been observed in oyster mushroom farms, resulting in crop losses.

The first reported appearance of green mould on P. ostreatus was in North America (Sharma and Vijay 1996). Serious cases of this disease in commercially grown P. ostreatus were detected thereafter in South Korea (Park et al. 2004a, b), Italy (Woo et al. 2004), Romania (Kredics et al. 2006), Hungary (Hatvani et al. 2007), and most recently in Spain (Gea 2009).

The causal agents of the Pleurotus green mould are two species of Trichoderma, which have been recently described as Trichoderma pleurotum S.H. Yu & M.S. Park and Trichoderma pleuroticola S.H. Yu & M.S. Park (Park et al. 2004a, b, 2006; Komon-Zelazowska et al. 2007). Phenotypically, T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola species are significantly different. T. pleuroticola shows a typical pachybasium-like conidiophore developing in fascicles or pustules which is typical for the Harzianum clade, whereas T. pleurotum is characterised by a gliocladium-like conidiophore morphology (Park et al. 2006; Komon-Zelazowska et al. 2007). In spite of the large phenetic divergence, these species present a very close phylogenetic relationship to the Harzianum clade of Hypocrea/Trichoderma, which also includes Trichoderma aggressivum Samuels & W. Gams, the causative agent of green mould disease in Agaricus (Park et al. 2004a, b; Hatvani et al. 2007; Komon-Zelazowska et al. 2007).

Trichoderma pleurotum has been found only on cultivated P. ostreatus and its substratum. In contrast, T. pleuroticola has been found both on wild and cultivated P. ostreatus, as well as on the natural and productive substratum of the oyster mushroom (Park et al. 2004a, b; Szekeres et al. 2005; Hatvani et al. 2007; Komon-Zelazowska et al. 2007; Kredics et al. 2009). Additionally, T. pleuroticola has been isolated from soil and wood in Canada, the USA, Europe, Iran, and New Zealand (Park et al. 2004a, b; Szekeres et al. 2005; Komon-Zelazowska et al. 2007).

Until now, it has not been clear which species of Trichoderma is the causative agent of the green mould in oyster mushroom farms of Central Europe. The present study was carried out to confirm the association of the T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola species with P. ostreatus cultivated in Poland based on morphological and molecular analysis of collected Trichoderma isolates originating from Polish oyster mushroom farms.

Materials and methods

Fungal collection

Four T. pleurotum (E135, E136, E138, E139) and five T. pleuroticola strains (E137, M141, M142, M143, M144), used as the reference strains, were kindly supplied by Dr. Monika Komon-Zelazowska, Research Area Gene Technology and Applied Biochemistry, Institute of Chemical Engineering, Vienna University of Technology, Austria. Eighty Trichoderma isolates were collected from green moulded cereal straw substrates at 47 oyster mushroom farms in Poland. The small fragments of cereal straw were taken from substrates used for cultivation of P. ostreatus. Basidiomes were suspended in 10 mL sterile distilled water and 0.2 mL Tween 20 (Sigma), incubated at 25 °C for 10 min on a rotary shaker (120 rpm) and diluted 1:10 with sterile distilled water. Inoculation was performed from the suspensions (0.5 mL) onto a potato dextrose agar (PDA, Oxoid) and incubated in darkness at 25 °C for 7 days. The resultant fungal colonies were transferred to new plates of PDA and incubated as described above. The strains collected from Polish mushroom farms and investigated in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The list of strains collected from oyster mushroom farms in Poland and identified on the basis of multiplex PCR and ITS and tef1 sequence analysis

| Culture code | Origin–localization | ITS and tef1 sequence-based identification | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of tef1 allelea | ||||

| T24//T | Western Poland | Babimost | T. pleuroticola | – |

| TH/24 | Babimost | T. harzianum | – | |

| T72/A | Budziłowo | T. pleurotum | “T” | |

| TV72/C | Budziłowo | T. atroviride | – | |

| T63/DR | Chobienice | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| T14/Ł | Chrosnica | T. pleurotum | “T” | |

| T58/2A | Kalisz | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| Tv57/2B | Kalisz | T. atroviride | – | |

| TB112 | Konin | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| T155 | Łobez | T. pleurotum | “T” | |

| TH55/F | Łobez | T. harzianum | – | |

| TH25/A | Łobez | T. harzianum | – | |

| TV55/Ł | Łobez | T. atroviride | – | |

| T16/2/Ab | Nądnia | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| T37/Ł | Nowy Tomyśl | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| TH370 | Nowy Tomyśl | T. harzianum | – | |

| Tv37/10 | Nowy Tomyśl | T. atroviride | – | |

| T71/B | Pleszew | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| T83/TB | Skoków | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| T12/Bb | Widzim Stary | T. pleuroticola | – | |

| TP53Ł | Wielichowo | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| Th530 | Wielichowo | T. harzianum | – | |

| T52/2D | Witaszyce | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| Tv52/G | Witaszyce | T. atroviride | – | |

| TP81R | Wolsztyn | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| T2/DR | Wroniary | T. pleurotum | “T” | |

| TP12/S | Northern Poland | Człopa | T. pleurotum | “T” |

| T05C | Gryfino | T. pleurotum | “T” | |

| TB40/M | Jakubowo Kisielickie | T. pleurotum | “T” | |

| T13/CB | Kamionki | T. pleurotum | “T” | |

| Tv130/A | Kamionki | T. atroviride | – | |

| T77/3 | Kłębowo | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| TB63 | Kłębowo | T. pleurotum | “T” | |

| Tv76/D | Kłębowo | T. atroviride | – | |

| Th76/K | Kłębowo | T. harzianum | – | |

| T50A | Kołaczkowo | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| T36/Bi | Koszalin | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| Tv37/Ci | Koszalin | T. atroviride | – | |

| T6/AR | Krępsko | T. pleurotum | “T” | |

| TP32M | Kudypy | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| TH320 | Kudyby | T. harzianum | – | |

| T41/T | Opatów | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| TH410 | Opatów | T. harzianum | – | |

| TB18A | Przechlewo | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| TP19/S | Zblewo | T. pleurotum | “T” | |

| Th19/B | Zblewo | T. harzianum | – | |

| T270/C | Żodyń | T. pleurotum | “T” | |

| Th271/B | Żodyń | T. harzianum | – | |

| TP17M | Eastern Poland | Garbów | T. pleurotum | “T” |

| TH17/7 | Garbów | T. harzianum | – | |

| T53B | Grodzisk Mazowiecki | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| TP25S | Łosice | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| TB73/L | Nowa Huta | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| TB6M | Radom | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| Th6/M4 | Radom | T. harzianum | – | |

| TP20S | Siedlce | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| T27/Z | Siedlce | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| Tv18/AB | Siedlce | T. atroviride | – | |

| TB27S | Wiśniew | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| T127 | Wola Łaska | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| Tv127/RU | Wola Łaska | T. atroviride | – | |

| T35Ab | Southern Poland | Bratkowice | T. pleurotum | “T” |

| TB33 | Brzeźnica | T. pleurotum | “T” | |

| TV/33a | Brzeźnica | T. atroviride | – | |

| TP11Ł | Bytom | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| T4/15/A | Czermin | T. pleurotum | “T” | |

| TH15/C | Czermin | T. harzianum | – | |

| TV17/C | Czermin | T. atroviride | – | |

| T158/1 | Ćwiklice | T. pleurotum | “T” | |

| TH58/2 | Ćwiklice | T. harzianum | – | |

| TP23M | Kraków | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| TB2 | Opole | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| Th2/33 | Opole | T. harzianum | – | |

| TB103 | Pszczyna | T. pleurotum | “N” | |

| Th10/PS | Pszczyna | T. harzianum | – | |

| Th11/PS | Pszczyna | T. harzianum | – | |

| Tv104/PS | Pszczyna | T. atroviride | – | |

| T55Z/2 | Ręczno | T. pleurotum | “T” | |

| TB108 | Smyków | T. pleurotum | “T” | |

| Tv18/AB | Smyków | T. atroviride | – | |

Morphological analysis

Identification was performed by observation of phenotypic characteristics of the colonies and by microscopic studies of the conidia and conidiophores. Colony characteristics were examined from cultures grown in darkness at 25 °C for 7 days on PDA. Microscopic observations were made according to Park et al. (2006).

DNA isolation and amplification

Mycelium for DNA extraction was obtained as described previously (Błaszczyk et al. 2011). Isolation of total DNA was performed using the CTAB method (Doohan et al. 1998).

The ITS1 and ITS2 region of the rDNA gene cluster was amplified using primers ITS4 and ITS5 (White et al. 1990). A fragment of 1.2-kb tef1 gene was amplified using primers Ef728M (Carbone and Kohn 1999) and TEF1LLErev (Jaklitsch et al. 2005) as well as the set of primers (FPforw1, FPrev1, PSrev1) designed for the rapid detection of T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola (Kredics et al. 2009).

The PCR reaction was carried out in 25 μL reaction mixture containing: 1 μL 50 ng/μL of DNA, 2.5 μL 10 × PCR buffer (50 mmol/L KCl, 1.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 10 mmol/L Tris–HCl, pH 8.8, 0.1 % Triton X-100), 1.5 μL 10 mmol/L dNTP (GH Healtcare), 0.2 μL 100 mmol/L of each primer, 19.35 μL MQ H2O, 0.25 μL (2 U/μL) DyNAzymeTM II DNA Polymerase (Finnzymes) using a PTC-200 thermocycler (MJ-Research, USA). A multiplex PCR assay with tef1 sequence-based primers FPforw1, FPrev1, PSrev1 was carried out under the conditions described by Kredics et al. (2009). Amplifications of ITS region and the fragment of tef1 gene were performed as follows: initial denaturation 5 min at 94 °C, 35 cycles of 45 s at 94 °C, 45 s at 58 °C (for ITS region) or 63 °C (for tef1 fragment), 1 min at 72 °C, with the final extension of 10 min at 72 °C.

Amplification products were separated on 1.5 % agarose gel (Invitrogen) in 1× TBE buffer (0.178 mol/L Tris-borate, 0.178 mol/L boric acid, 0.004 mol/L EDTA) containing ethidium bromide. A 100-bp DNA Ladder Plus (Fermentas) was used as a size standard. PCR products were electrophoresed at 3 V/cm for about 2 h, visualized under UV light, and photographed (Syngen UV visualiser).

DNA sequencing and comparative analyses

The 0.4-kb ITS and 1.2-kb tef1 amplicon purification steps and sequencing were carried out as described previously (Chełkowski et al. 2003; Błaszczyk et al. 2011). Sequences were edited and assembled using Chromas v. 1.43 (Applied Biosystems). The sequences were identified by BLASTn (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) as well as TrichOKEY and TrichoBLAST (http://www.isth.info; Druzhinina et al. 2005; Kopchinskiy et al. 2005).

The comparative analyses were based on the ITS and tef1 sequences of the 49 T. pleurotum/T. pleuroticola isolates obtained in the present study and 9 reference strains, as well as on the sequences of 21 other T. pleurotum/T. pleuroticola strains, deposited in NCBI GeneBank (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, Table 2). The sequences of 8 T. pleurotum, and 13 T. pleuroticola strains, sourced from Hungary, Italy, Romania, Canada, USA, Netherlands, and Colombia, were used in order to determine the relationship of these strains and the isolates originating from Poland. ClustalW (Thompson et al. 1994) was used to align the sequences.

Table 2.

The list of Trichoderma strains selected from the NCBI GeneBank database and used for the comparative analysis

| Strain no. | Other collection | Origin | Habitat | NCBI GenBank accession no. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | tef1 | ||||

| T. pleurotum | |||||

| C.P.K. 2113 | CBS121147, DAOM 236051 | Hungary | P. ostreatus substratum | EF392808 | EF392773 |

| C.P.K. 2096 | Hungary | P. ostreatus substratum | EF392797 | EF392770 | |

| C.P.K.2097 | Hungary | P. ostreatus substratum | EF392798 | EF392771 | |

| C.P.K. 2100 | Hungary | P. ostreatus substratum | EF392801 | EF392772 | |

| C.P.K. 2116 | CBS 121148 | Hungary | P. ostreatus substratum | EF392810 | EF392774 |

| C.P.K. 2117 | Hungary | P. ostreatus substratum | EF392811 | EF392775 | |

| C.P.K. 1532 | CBS 121216 | Italy | P. ostreatus substratum | EF392795 | EF601678 |

| C.P.K. 2815 | Romania | P. ostreatus substratum | EF601675 | EF601680 | |

| T. pleuroticola | |||||

| DAOM 175924 | CBS121144 | Canada | Acer sp. | AY605726 | AY605769 |

| DAOM 229916 | USA | Forest soil | AY605738 | AY605781 | |

| C.P.K. 1540 | CBS 121217 | Italy | P. ostreatus incubating bales | EF392782 | EF392762 |

| C.P.K. 1544 | Italy | P. ostreatus incubating bales | EF392786 | EF392763 | |

| C.P.K. 1550 | Italy | Mushroom farm | EF392791 | EF392765 | |

| C.P.K. 1551 | Italy | Mushroom farm | EF392792 | EF392766 | |

| C.P.K. 2104 | CBS 121145 | Hungary | P. ostreatus substratum | EF392794 | EF392769 |

| C.P.K. 3266 | Hungary | Populus Canadensis stump | EU918148 | EU918160 | |

| C.P.K. 3193 | Hungary | Populus alba stump | EU918140 | EU918160 | |

| C.P.K. 2816 | Romania | P. ostreatus substratum | EF601676 | EF601681 | |

| C.P.K. 2817 | Romania | P. ostreatus substratum | EF601677 | EF601682 | |

| G.J.S. 95-81 | The Netherlands | Pleurotus spawn | AF345948 | AF348102 | |

| T 1295 | Colombia | Soil | EU280071.1 | EU279973.1 | |

Results

Identification of T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola isolates

Preliminary identifications of the 80 Trichoderma isolates collected from the 47 oyster mushroom farms in Poland and 9 reference strains (E135, E136, E137, E138, E139, M141, M142, M143, M144) were based both on phenetic observations and multiplex PCR assay. PCR amplification with primers FPforw1, FPrev1, and PSrev1 expressed 447- and 218-bp fragments in 47 examined isolates and 4 reference strains (E135, E136, E138, E139), characterised as T. pleurotum. Only the larger band of 447 bp was observed in two examined isolates (T12/B, T24/T) and five references strains (E137, M141, M142, M143, M144) of Trichoderma. This indicated the presence of T. pleuroticola. However, no amplified product was detected in the remaining (31) Trichoderma isolates.

The initial identifications of 2 T. pleuroticola and 47 T. pleurotum isolates collected from Poland as well as 9 reference Trichoderma strains were confirmed by sequencing two different phylogenetic markers: the fragment of the ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 rRNA region and the fragment of the tef1 gene (Table 1). The sequence analyses were also used to identify the remaining Trichoderma isolates collected from oyster mushroom farms in Poland. These isolates were identified as Trichoderma harzianum Rifai (17 isolates) and Trichoderma atroviride P. Karst (14 isolates) (Table 1).

Comparison of ITS and tef1 sequences of T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola isolates

The comparative analyses were based on the ITS and tef1 sequences of the T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola strains both obtained in this study and published previously by Hatvani et al. (2007), Komon-Zelazowska et al. (2007), and Kredics et al. (2009).

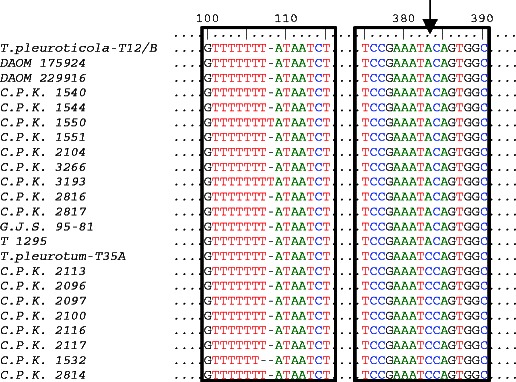

DNA sequence alignment showed that the ITS allele detected in 47 T. pleurotum isolates from Poland was identical to that of T. pleurotum strains from Hungary (C.P.K. 2113, C.P.K. 2096, C.P.K. 2097, C.P.K. 2100, C.P.K. 2116, C.P.K. 2117) and Romania (C.P.K. 2814) but differed by one single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) from the Italian strain C.P.K. 1532. Similarly, 2 T. pleuroticola isolates from Poland and 11 strains from: Canada (DAOM 175924), USA (DAOM 22996), Italy (C.P.K. 1540), Romania (C.P.K. 2816, C.P.K. 2817), Hungary (C.P.K. 2104, C.P.K. 3266), Netherlands (G.J.S. 95–81), and Colombia (T 1295) possessed an identical allele in the ITS locus, while their ITS1 sequences were different by one SNP from the sequences of Italian strain C.P.K. 1550 and Hungarian strain C.P.K. 3193. Single nucleotide polymorphism (A/C transversion) was also observed between ITS alleles of T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola isolates used in the present study. The intra- and interspecies variability in the ITS sequences, deriving from single nucleotide indel or transition (A-C), is given in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The intra- and interspecies variability in the ITS sequences of selected T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola isolates from oyster mushroom farms in Poland and strains deposited in NCBI GeneBank (Tables 1 and 2). The nucleotide polymorphism for T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola strains are enclosed. Single nucleotide polymorphism (A/C transversion) between ITS alleles of T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola is shown by the arrow

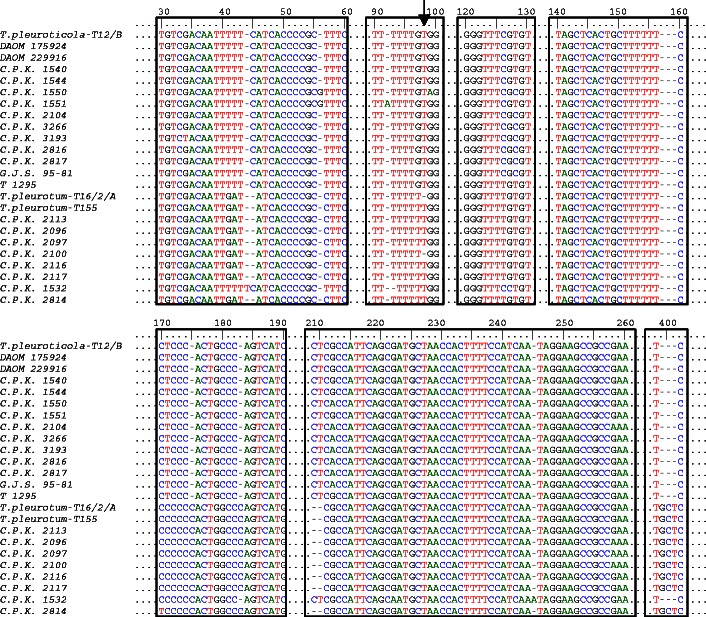

As shown in Fig. 2, T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola were clearly divergent in the tef1 analysis. Their tef1 sequences were separated by several indel and nucleotide substitutions. The set of 47 T. pleurotum isolates originating from Poland were found to be polymorphic and represented two tef1 alleles (“T” type and “N” type), distinguishable based on one single nucleotide insertion/deletion (Fig. 2, Table 1). Nineteen Polish isolates of T. pleurotum possess the tef1 allele (“T” type) identical to three isolates from Hungary (C.P.K. 2113, C.P.K. 2116, C.P.K. 2117) and Romania (C.P.K. 2814), but different from the alleles represented by Hungarian strain C.P.K. 2096, C.P.K. 2097, and C.P.K. 2100, and Italian strain C.P.K. 1532. The “N” type of the tef1 allele, found in the remaining T. pleurotum isolates from Poland, has one position (indel or transition A/G) that differs from the allele type of five strains from Hungary (C.P.K. 2113, C.P.K. 2116, C.P.K. 2117, C.P.K. 2110) and Romania (C.P.K. 2814), two positions (indel and transition A/G) that differ from the allele type of two Hungarian strains C.P.K. 2096 and C.P.K. 2097, and several positions that differ from the allele type of Italian strain C.P.K. 1532. The tef1 sequences of two T. pleuroticola isolates from Poland were identical to that of T. pleuroticola strains DAOM 175924 from Canada, DAOM 229916 from the USA, and C.P.K. 1540 and C.P.K. 1544 from Italy, but different by four A/G and T/C transitions from the sequences of C.P.K. 3266, C.P.K. 3193, C.P.K. 2816, C.P.K. 2817, and T 1295 strains. More polymorphism was detected between the tef1 sequences of Polish T. pleuroticola isolates and that of C.P.K. 2104, C.P.K. 1550, and C.P.K. 1551 strains.

Fig. 2.

The intra- and interspecies variability in the tef1 sequences of selected T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola isolates from oyster mushroom farms in Poland and strains deposited in NCBI GeneBank (Tables 1 and 2). The nucleotide polymorphism for T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola strains are enclosed. Single nucleotide insertion/deletion (“T”/“N” allele) between Polish T. pleuroticola isolates is shown by the arrow

Discussion

The present study states the association of T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola with Pleurotus green mould in Polish mushroom farms. T. pleurotum was also the most common species collected from Hungarian oyster mushroom farms (Komon-Zelazowska et al. 2007). The predominance of T. pleurotum species in samples originating from Polish and Hungarian Pleurotus farms may be due to the use of similar technologies in the production of cereal straw substratum for mushroom cultivation. These technologies are different from the methods used in Italy (probably adverse for the T. pleurotum infection), where T. pleuroticola was the major contaminant of Pleurotus substratum (Komon-Zelazowska et al. 2007).

Other species isolated from green moulded substrata for Pleurotus cultivation in Poland were: T. harzianum and T. atroviride. The presence of these species in the cultivation of P. ostreatus was also noted by Hatvani et al. (2007). Additionally, Hatvani et al. (2007) found individual isolates of Trichoderma longibrachiatum Rifai, Trichoderma ghanense Yoshim. Doi, Y. Abe & Sugiy, and Trichoderma asperellum Samuels, Lieckf. & Nirenberg. Five of these seven species, namely T. pleuroticola, T. harzianum, T. atroviride, T. longibrachiatum, and T. asperellum, were isolated from the substrate and the basidiomes of wild-grown P. ostreatus in Hungary. T. pleurotum was not found in these samples.

The preliminary identification of the collected Trichoderma isolates was based on phenetic observations and multiplex PCR assay. DNA markers used in the present work and specific for T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola were recently described by Kredics et al. (2009). These authors (Kredics et al. 2009) demonstrated that T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola can be distinguished from each other, as well as from other fungal species, using three oligonucleotide primers: FPforw1, FPrev1, and PSrev1, based on tef1 sequences. The present paper validates the specificity and the usefulness of the multiplex PCR assay developed by Kredics et al. (2009). As shown here, the PCR markers enabled the rapid screening of 80 Trichoderma isolates and specific detection of T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola, collected from green moulded substrata for Pleurotus cultivation.

The ITS and tef1 sequence information was used to establish the intra- and interspecies relationship of T. pleurotum and T. pleuroticola originating from the oyster mushroom farms in Poland and those from other countries. The comparative analysis of the ITS sequences showed that all T. pleurotum isolates from Poland represent one haplotype, identical to that of T. pleurotum strains C.P.K. 2113, C.P.K. 2096, C.P.K. 2097, C.P.K. 2100, C.P.K. 2116, C.P.K. 2117 from Hungary and C.P.K. 2814 from Romania, but different from Italian strain C.P.K. 1532. However, the sequence analysis of the tef1 locus revealed two haplotypes of Polish T. pleurotum isolates—“T” type and “N” type. The “T” type isolates of T. pleurotum have identical tef1 allele to that of strains C.P.K. 2113, C.P.K. 2116, C.P.K. 2117 from Hungary and C.P.K. 2814 from Romania, whereas the “N” type isolates are unique at the tef1 locus. As observed in the present study, the distribution of “T” type and “N” type isolates in Poland is not correlated with the location of the mushroom farms from which they originated (Table 1). According to a previous study (Komon-Zelazowska et al. 2007), the source of T. pleurotum infection is the substratum for mushroom cultivation. Thus, the composition of two T. pleurotum haplotypes most likely depends on the manufacturer (source) of the cereal straw substratum used for the mushroom cultivation. The trading (import–export) of the Pleurotus substratum among European countries could also explain the identicalness of the “T” type isolates to the Hungarian and Romanian T. pleurotum strains. Interestingly, a similar mechanism of T. aggressivum distribution in Agaricus mushroom farms has been observed (Hatvani et al. 2007). It is noteworthy that T. aggressivum, just like T. pleurotum, has so far never been isolated from the natural environment. As observed in the previous studies, the major source of T. aggressivum infection was the compost and the origin of its constituents (Hatvani et al. 2007; Komon-Zelazowska et al. 2007). Hatvani et al. (2007) performed the comparison of two populations of T. aggressivum f. europaeum isolates from the British Islands and Hungary. The analysis of mtDNA showed that Hungarian isolates of T. aggressivum f. europaeum belong to the same population as the first isolates from Northern Ireland and England, while they all proved to be clearly different from T. aggressivum f. aggressivum isolates. Furthermore, the complete identity or low levels of variability of ITS1 and ITS2 sequences were also observed for T. aggressivum f. europaeum strains examined by Muthumeenakshi et al. (1998), Samuels et al. (2002), and Błaszczyk et al. (2011). These studies indicated that T. aggressivum f. europaeum strains most likely derived from the Western European epidemic lineage.

The detailed analysis of the ITS and tef1 sequences showed that two T. pleuroticola isolates from Polish mushroom farms are identical to strains DAOM 175924 from Canada, DAOM 229916 from the USA, and C.P.K. 1540 and C.P.K 1544 from Italy, whereas they are different from the Hungarian and Romanian strains. It is known that T. pleuroticola occur in association with P. ostreatus growing in natural environments and in mushroom farms (Park et al. 2004a, b, 2006; Szekeres et al. 2005; Komon-Zelazowska et al. 2007; Kredics et al. 2009). This is why the sources of T. pleuroticola infection may be various (Kredics et al. 2009). A study of the vectors for T. pleuroticola into mushroom farms could explain the distribution of this pathogenic species in Polish mushroom farms. This need is highlighted by the present paper and previous work (Komon-Zelazowska et al. 2007).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland, project no. NN310 203037.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- Błaszczyk L, Popiel D, Chełkowski J, Koczyk G, Samuels GJ, Sobieralski K, Siwulski M. Species diversity of Trichoderma in Poland. J Appl Genetics. 2011;52:233–243. doi: 10.1007/s13353-011-0039-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone I, Kohn LM. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia. 1999;91:553–556. doi: 10.2307/3761358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chełkowski J, Golka L, Stępień Ł. Application of STS markers for leaf rust resistance genes in near-isogenic lines of spring wheat cv. Thatcher. J App Genet. 2003;44:323–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doohan FM, Parry DW, Jenkinson P, Nicholson P. The use of species-specific PCR-based assays to analyse Fusarium ear blight of wheat. Plant Pathol. 1998;47:197–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3059.1998.00218.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Druzhinina IS, Kopchinskiy AG, Komon M, Bissett J, Szakacs G, Kubicek CP. An oligonucleotide barcode for species identification in Trichoderma and Hypocrea. Fungal Genet Biol. 2005;42:813–828. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gea FJ. First report of Trichoderma pleurotum on oyster mushroom crops in Spain. J Plant Pathol. 2009;91:504. [Google Scholar]

- Hatvani L, Antal Z, Manczinger L, Szekeres A, Druzhinina IS, Kubicek CP, Nagy A, Nagy E, Vágvölgyi C, Kredics L. Green mould diseases of Agaricus and Pleurotus spp. are caused by related but phylogenetically different Trichoderma species. Phytopathology. 2007;97:532–537. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-97-4-0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaklitsch WM, Komon M, Kubicek CP, Druzhinina IS. Hypocrea voglmayrii sp. nov. from the Austrian Alps represents a new phylogenetic clade in Hypocrea/Trichoderma. Mycologia. 2005;97:1365–1378. doi: 10.3852/mycologia.97.6.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komon-Zelazowska M, Bisset J, Zafari D, Hatvani L, Manczinger L, Woo S, Lorito M, Kredics L, Kubicek CP, Druzhinina IS. Genetically closely related but phenotypically divergent Trichoderma species cause green mold disease in oyster mushroom farms worldwide. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:7415–7426. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01059-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopchinskiy A, Komon M, Kubicek CP, Druzhinina IS. TrichoBLAST: a multilocus database for Trichoderma and Hypocrea identifications. Mycol Res. 2005;109:657–660. doi: 10.1017/S0953756205233397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kredics L, Hatvani L, Antal Z, Manczinger L, Druzhinina IS, Kubicek CP, Szekeres A, Nagy A, Vágvölgyi C, Nagy E. Green mould disease of oyster mushroom in Hungary and Transylvania. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2006;53:306–307. [Google Scholar]

- Kredics L, Kocsube S, Nagy L, Komon-Zelazowska M, Manczinger L, Sajben E, Nagy A, Vagvolgyi C, Kubicek CP, Druzhinina IS, Hatvani L. Molecular identification of Trichoderma species associated with Pleurotus ostreatus and natural substrates of the oyster mushroom. Microb Lett. 2009;300:58–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthumeenakshi S, Brown AE, Mills PR. Genetic comparison of the aggressive weed mould strains of Trichoderma harzianum from mushroom compost in North America and the British Isles. Mycol Res. 1998;102:385–390. doi: 10.1017/S0953756297004759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park MS, Bae KS, Yu SH. Molecular and morphological analysis of Trichoderma isolates associated with green mold epidemic of oyster mushroom in Korea. J Huazhong Agric Univ. 2004;23:157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Park MS, Bae KS, Yu SH (2004b) Morphological and molecular analysis of Trichoderma species associated with green mold epidemic of oyster mushroom in Korea. New Challenges in Mushroom Science. Proceedings of the 3rd Meeting of Far East Asia for Collaboration on Edible Fungi Research, Suwon, Korea, pp 143–158

- Park MS, Bae KS, Yu SH. Two new species of Trichoderma associated with green mold of oyster mushroom cultivation in Korea. Mycobiology. 2006;34:111–113. doi: 10.4489/MYCO.2006.34.3.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels GJ, Dodd SL, Gams W, Castlebury LA, Petrini O. Trichoderma species associated with the green mold epidemic of commercially grown Agaricus bisporus. Mycologia. 2002;94:146–170. doi: 10.2307/3761854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szekeres A, Kredics L, Antal Z, Hatvani L, Manczinger L, Vágvölgyi C. Genetic diversity of Trichoderma strains isolated from winter wheat rhizosphere in Hungary. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2005;52:156. doi: 10.1556/AMicr.52.2005.2.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SR, Vijay B. Yield loss in Pleurotus ostreatus spp. caused by Trichoderma viride. Mushroom Res. 1996;5:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTALW: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor JW. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Shinsky JJ, White TJ, editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. San Diego: Academic; 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Woo SL, Di Benedetto P, Senatore M, Abadi K, Gigante S, Soriente I, Ferraioli S, Scala F, Lorito M. Identification and characterization of Trichoderma species aggressive to Pleurotus in Italy. J Zhejiang Univ Agric Life Sci. 2004;30:469–470. [Google Scholar]