Abstract

Objective:

The cross-sectional study was carried out to assess the iodine status of pregnant women, using median urinary iodine concentration (MUI) as the measure of outcome, to document the impact of advancing gestation on the MUI in normal pregnancy.

Materials and Methods:

The present study assessed the MUI in casual urine samples from 50 pregnant subjects of each trimester and 50 age-matched non-pregnant controls.

Results:

The median (range) of urinary iodine concentration (UIC) in pregnant women was 304 (102-859) μg/L and only 2% of the subjects had prevalence of values under 150 μg/L (iodine insufficiency). With regard to the study cohort, median (range) UIC in the first, second, and third trimesters was 285 (102-457), 318 (102-805), and 304 (172-859) μg/L, respectively. Differences between the first, second, and third trimesters were not statistically significant. The MUI in the controls (305 μg/L) was not statistically different from the study cohort.

Conclusion:

The pregnant women had no iodine deficiency, rather had high median urinary iodine concentrations indicating more than adequate iodine intake. Larger community-based studies are required in iodine-sufficient populations, to establish gestation-appropriate reference ranges for UIC in pregnancy.

Keywords: Gestation, iodine deficiency, pregnancy, thyroid, urinary iodine concentration

INTRODUCTION

Iodine is an essential micronutrient required for thyroid hormone synthesis, to maintain homeostasis. Its role in fetal and early childhood brain development is emphasized by studies showing iodine deficiency in pregnancy associated with stunted growth and neuromotor, intellectual, behavioral, and cognitive impairment, as well as, cretinism in severe cases.[1,2,3]

The outcome indicators of iodine nutrition in a community include the goiter rate and median urinary iodine (MUI) in school children (age 6-12 years), serum TSH in neonates, and thyroglobulin in the general population. The key indicator of population iodine nutrition recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Council for Control of Iodine Deficiency Disorders (ICCIDD) is the determination of median urinary iodine concentration in a representative sample of school-aged children.[4] The adequacy of iodine nutrition is defined by the following criteria: A median MUI of at least 100 μg/L (with <20% of the population having MUI <50 μg/L) represents adequate population iodine nutrition; a median MUI between 50 and 99 μg/L represents mild iodine deficiency; and medians of 20-49 μg/L and <20 μg/L represent moderate and severe iodine deficiency, respectively.

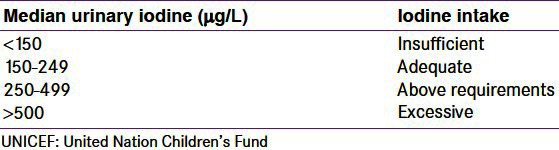

The majority of dietary iodine (>90%) is excreted in the urine.[5] Urine iodine excretion (UIE) is largely a passive process dependent on glomerular filtration rate (GFR). The UIE in a non-pregnant individual on a stable diet represents a dynamic equilibrium between dietary intake, thyroidal iodine extraction, the total body thyroid hormone pool, and GFR. During normal pregnancy, GFR increases within the first month following conception, peaking by the end of the first trimester by approximately 40-50% above pre-pregnant levels.[6] Hence, pregnancy can be expected to result in increased renal iodine loss. Increased ioduria during early pregnancy, resulting from increased GFR is likely to be the explanation for the potential overestimation of iodine nutrition in pregnancy, using UIE. This has the capacity to conceal the degree of iodine deficiency, which only becomes fully evident in these subjects in the latter stages of pregnancy. The reference ranges recommended in children would not be adequate for optimum iodine nutrition in pregnancy. Taking these physiological changes into consideration, the WHO and the American Thyroid Association have recommended higher pregnancy-specific urinary iodine ranges,[7,8] as provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Epidemiological criteria based on the World Health Organization, UNICEF, and International Council for Control of Lodine Deficiency Disorders guidelines for assessing iodine nutrition based on the median or range in urinary iodine excretion of pregnant women

In India, following universal salt iodization, there have been several reports of normalization of iodine nutrition as reflected by MUI in school children.[9,10,11] However, very few studies have looked at iodine nutrition in pregnancy, with even fewer providing trimester-specific details,[12,13,14] with no trimester-specific reports from India. We have undertaken this study to assess iodine nutrition by MUI in pregnant women of different trimesters attending a tertiary care center in Delhi.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism in collaboration with the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, AIIMS, after due ethical approval. Fifty consecutive women of each trimester of pregnancy, attending the antenatal clinic, were recruited after informed voluntary consent. Fifty non-pregnant, age-matched, adult female attendants accompanying patients in the clinic were recruited as controls. A detailed history and physical examination was conducted and noted in the proforma. A single morning sample of urine was collected from each participant in a screw capped plastic bottle and stored at 4°C in the laboratory till analysis. Urinary iodine content was estimated by the wet ashing method based on the Sandell–Koltoff reaction, using the perchloric acid vanadate system, originally used by Zak and Baginski, for serum-protein bound iodine, modified and adopted in our laboratory for urine iodine estimation.[15] The median urinary iodine concentration was defined as a concentration of iodine in a spot urine sample and the results were expressed as micrograms per liter (μg/l). Inter-assay and intra-assay coefficients of variation (CVs) for quality control were 9 and 7%, respectively.

RESULTS

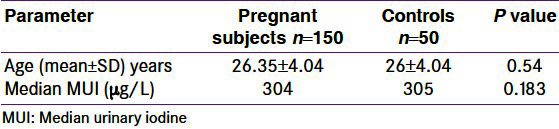

One hundred and fifty pregnant women and fifty non-pregnant control women formed a part of the study. The mean age of the pregnant women was 26.35 ± 4.05 (19-38) years, while that of the controls was 26 ± 4.04 (22-36) years, with no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.54). The trimester-specific gestational ages were 11.4 ± 2.8, 26 ± 2.1, and 36.1 ± 2.0 weeks, respectively.

Median urinary iodine concentration in the cohort of pregnant women was 304 μg/L with 2.5th percentile being 171.8 μg/L and 97.5th percentile being 794 μg/L, while that in the controls was 305 μg/L. There was no significant difference in the MUI between the pregnant women and controls [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of characteristics of pregnant and control subjects

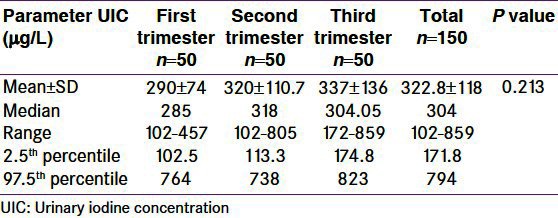

Trimester-specific details of the MUI are provided in Table 3. The median MUIs for the first, second, and third trimesters were 285 μg/L, 318 μg/L, and 304.5 μg/L, respectively, indicating a rise from the first to the second trimester, followed by a small fall again in the third trimester, but it was not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Mean, median, 2.5th, and 97.5th percentiles of urinary iodine concentration in reference population

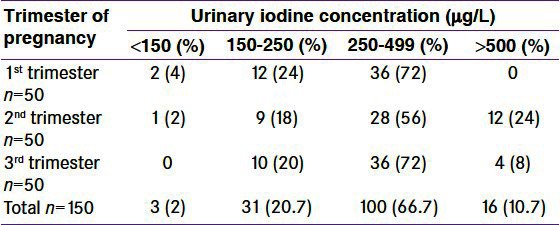

Using the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, iodine nutrition, as assessed by the MUI of this cohort of pregnant women, is described in Table 4. Only 2% of the pregnant women had iodine deficiency, while 78% had more than adequate iodine nutrition.

Table 4.

Frequency distribution of median urinary iodine concentration by trimester of pregnancy in the cohort of pregnant women

DISCUSSION

Iodine is an essential micronutrient throughout life. During pregnancy, various physiological changes result in increased iodine requirements. Increase in renal blood flow and GFR results in increased urinary iodine excretion, as most iodine is excreted by a passive process in the urine. Increased maternal thyroid hormone synthesis to maintain euthyroidism and provide thyroid hormones to the fetus as well as transfer of iodine to the fetus add to the increasing iodine requirements during pregnancy.[16,17]

Studies on iodine nutrition in pregnancy, based on median urinary iodine excretion, have been far and few. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) I (1971-1974) showed the median MUI in pregnancy to be 327 μg/L compared to 293 μg/L in non-pregnant women.[18] In the NHANES III (1988-1994), the median MUI in pregnancy was 141 μg/L compared to 127 μg/L in non-pregnant women, while in NHANES 2001-2002, the same were 172.6 μg/L and 132 μg/L, respectively.[19] Consequently, the MUI concentration in children cannot be used to define normal iodine nutrition in pregnancy. Based on these and other studies, the WHO has revised the reference range of MUI for adequate iodine nutrition in pregnancy from 150 to 250 μg/L and the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for iodine in pregnancy from 200 to 250 μg.[7]

Iodine deficiency has been endemic in India for a long time. Following the implementation of the National Iodine Deficiency Disorders Control Program (NIDDCP) based on Universal Salt Iodization (USI), iodine sufficiency has been achieved in many parts of the country. These studies have assessed the median MUI in school-age children and have shown that the median MUI has increased over the last two decades with evidence of more-than-adequate iodine nutrition in recent studies.[9,10,11,20]

The data on iodine nutrition in pregnancy from the country are scant. A study of 680 pregnant women of the second and third trimesters from the lower socioeconomic strata of Delhi, conducted in 1998, showed iodine deficiency defined as MUI <100 μg/L, in 23%. Other details were not provided.[21] Another study by the same authors in 151 rural adolescent pregnant mothers from Uttaranchal, in 2003, reported MUI as 95 μg/L; with iodine deficiency reported in 57% and a goiter rate of 15%.[22] A hospital-based study on 200 term women from Chandigarh reported iodine deficiency in only 2.5% and an MUI of 240-320 μg/L.[23] Chakraborty et al. from West Bengal (2004) showed the MUI in 267 full-term pregnant women to be 144 ug/L, compared to levels of 130 ug/L in 100 non-pregnant controls. Iodine deficiency was reported in 22% of pregnant women, while 12% had an MUI of >200 μg/L.[24] A recent community-based study conducted in 360 pregnant women from Rajasthan showed the MUI to be 127 μg/L with 43% having iodine deficiency.[25]

Our study showed iodine deficiency in only 2% of the pregnant women with more than adequate iodine nutrition (MUI <250 μg/L) in nearly 80%. These findings, while not entirely in concordance with the studies of iodine nutrition in pregnancy from most other parts of the country, are consistent with the findings reported on community iodine nutrition, in recent times, from Delhi.[10,11] The higher MUI in pregnant as well as non-pregnant subjects may be due to an improvement in the implementation of USI, over time. Other factors like the methodology of urinary iodine estimation, selectivity of study population, and non-salt sources of iodine may have contributed to the high MUI in the present study. The role of seasonal variation in MUI is also emphasized.[26] Although many studies[8,13,14] have shown higher MUI in pregnancy compared to non-pregnant women, we have found similar levels in both groups. This may be due to the small size of the study population as well as the overall trend in the iodine nutrition mentioned earlier.

Trimester-specific MUI has been reported only in a few studies worldwide, with no reports from India. In pregnant women with iodine restriction, the UIC may transiently show an early increase, due to an increase in the GFR, and thereafter, a steady decrease in UIC from the first to the third trimesters of gestation, thus revealing the underlying tendency toward iodine deficiency associated with the pregnant state, whereas, in iodine-sufficient areas there may be no decline. Studies in populations with mild iodine deficiency from communities in Switzerland,[14] UK,[12] and Hong Kong,[13] which provide gestation-specific data, show an overall increase in ioduria in pregnancy, as compared to non-pregnant women of reproductive age. In a prospective study from iodine-replete Iran, MUI in the three trimesters were 193 μg/L, 159 μg/L, and 141 μg/L, respectively, a decrescendo pattern, with significant inter-trimester variation and values reaching inadequate levels in the third trimester.[27] A prospective study from the iodine-deficient Tasmania revealed that the MUI declines initially up to week 22, and subsequently rises up to week 34, only to fall again till term;[28] the data from the iodine-sufficient Hong Kong, revealed an increasing level of ioduria with advancing gestation.[13] We found MUIs of 285 μg/L, 318 μg/L, and 304.5 μg/L in the three trimesters; levels above normal in all trimesters, with a peak in mid-pregnancy.

The explanation for these differences is unclear, but ethnic variation in the diet structure or degree of overall iodine deficiency may play a role. Although no reference ranges for trimester-specific MUI are available; they need to be generated using an iodine-sufficient pregnant population. Such a population must have an MUI at least similar to non-pregnant women, with values not declining during pregnancy. Taking these into consideration, our population can be termed as iodine-sufficient, as there has been no difference in the MUI of the controls and there has been no inter-trimester variation, without any values in the insufficient range.

Limitations of our study include the use of a hospital-based cohort preventing it from being representative of the iodine nutrition of the community. We have neither assessed the salt intake nor the salt iodine content. However, others have shown a high consumption of iodized salt in Delhi households.[29] As we have not reported iodine deficiency, this should not affect our results. We have not assessed the use of vitamin-mineral preparations in pregnancy, which could have contributed to a higher MUI. However, results in the controls have also been similar, thereby negating the role of any such preparation, solely in pregnancy.

In conclusion, this small hospital-based study of pregnant women in Delhi is the first to provide trimester ranges for urinary iodine concentrations in an iodine-sufficient population. Even as this may not be representative of community iodine nutrition, it calls for similar large studies in community settings to provide information on iodine nutrition in different trimesters of pregnancy, to generate trimester-specific reference ranges, as urinary iodine concentration needs to be determined for better assessment of iodine nutrition in pregnancy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: No

REFERENCES

- 1.Glinoer D. The regulation of thyroid function during normal pregnancy: Importance of the iodine nutrition status. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;18:133–52. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delange F. Iodine deficiency as a cause of brain damage. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:217–20. doi: 10.1136/pmj.77.906.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delange F. The role of iodine in brain development. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59:75–9. doi: 10.1017/s0029665100000094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organisation. A guide for program managers. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. Assessment of iodine deficiency disorders and monitoring their elimination. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delange F. Optimal Iodine Nutrition during Pregnancy, Lactation and the Neonatal Period. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2004;2:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davison JM, Dunlop W. Renal hemodynamics and tubular function in normal human pregnancy. Kidney Int. 1980;18:152. doi: 10.1038/ki.1980.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO, UNICEF, ICCIDD. A guide for programme managers. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. Assessment of the iodine deficiency disorders and monitoring their elimination. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Public Health Committee of the American Thyroid Association. Iodine supplementation for pregnancy and lactation-United States and Canada: Recommendations of the American Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2006;16:949–51. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.16.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marwaha RK, Tandon N, Gupta N, Karak AK, Verma K, Kochupillai N. Residual goitre in the postiodization phase: Iodine status, thiocyanate exposure and autoimmunity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2003;59:672–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marwaha RK, Tandon N, Desai A, Kanwar R, Grewal K, Aggarwal R, et al. Reference range of thyroid hormones in normal Indian school-age children. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;68:369–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marwaha RK, Tandon N, Desai A, Kanwar R, Mani K. Iodine nutrition in upper socioeconomic school children of Delhi. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:335–8. doi: 10.1007/s13312-010-0063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smyth PP. Variation in iodine handling during normal pregnancy. Thyroid. 1999;9:637–42. doi: 10.1089/thy.1999.9.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kung AW, Lao TT, Chau MT, Tam SC, Low LC. Goitrogenesis during pregnancy and neonatal hypothyroxinaemia in a borderline iodine sufficient area. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2000;53:725–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2000.01156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brander L, Als C, Buess H, Haldimann F, Harder M, Hänggi W, et al. Urinary iodine concentration during pregnancy in an area of unstable dietary iodine intake in Switzerland. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003;26:389–96. doi: 10.1007/BF03345192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zak B, Baginski ES. Protein bound estimation. In: Frankyl S, Rietman S, editors. Gradwohls’ clinical laboratory and diagnosis. St. Louis: The CV Mosby Company; 1970. p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burrow GN. Thyroid function and hyperfunction during gestation. Endocr Rev. 1993;14:194–202. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-2-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glinoer D. The regulation of thyroid function in pregnancy: Pathways of endocrine adaptation from physiology to pathophysiology. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:404–33. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.3.0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Hannon WH, Flanders DW, Gunter EW, Maberly GF, et al. Iodine nutrition in the United States. Trends and public health implications: Iodine excretion data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys I and III (1971-1974 and 1988-1994) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:3401–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.10.5168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caldwell KL, Jones R, Hollowell JG. Urinary iodine concentration: United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001-2002. Thyroid. 2005;15:692–9. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menon UV, Sundaram KR, Unnikrishnan AG, Jayakumar RV, Nair V, Kumar H. High prevalence of undetected thyroid disorders in an iodine sufficient adult south Indian population. J Indian Med Assoc. 2009;107:72–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapil U, Pathak P, Tandon M, Singh C, Pradhan R, Dwivedi SN. Micronutrient deficiency disorders amongst pregnant women in three urban slum communities of Delhi. Indian Pediatr. 1999;36:983–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pathak P, Singh P, Kapil U, Raghuvanshi RS. Prevalence of iron, vitamin A, and iodine deficiencies amongst adolescent pregnant mothers. Indian J Pediatr. 2003;70:299–301. doi: 10.1007/BF02723584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh B, Ezhilarasan R, Kumar P, Narang A. Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia and its association with thyroid hormone levels and urinary iodine excretion. Indian J Pediatr. 2003;70:311–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02723587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chakraborty I, Chatterjee S, Bhadra D, Mukhopadhyaya BB, Dasgupta A, Purkait B. Iodine deficiency disorders among the pregnant women in a rural hospital of West Bengal. Indian J Med Res. 2006;123:825–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ategbo EA, Sankar R, Schultink W, van der Haar F, Pandav CS. An assessment of progress toward universal salt iodization in Rajasthan, India, using iodine nutrition indicators in school-aged children and pregnant women from the same households. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulze KJ, West KP, Jr, Gautschi LA, Dreyfuss ML, LeClerq SC, Dahal BR, et al. Seasonality in urinary and household salt iodine content among pregnant and lactating women of the plains of Nepal. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:969–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ainy E, Ordookhani A, Hedayati M, Azizi F. Assessment of intertrimester and seasonal variations of urinary iodine concentration during pregnancy in an iodine-replete area. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;67:577–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stilwell G, Reynolds PJ, Parameswaran V, Blizzard L, Greenaway TM, Burgess JR. The influence of gestational stage on urinary iodine excretion in pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1737–42. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agarwal J, Pandav CS, Karmarkar MG, Nair S. Community monitoring of the National Iodine Deficiency Disorders Control Programme in the National Capital Region of Delhi. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14:754–7. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010000297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]