Abstract

The purpose of this systematic review was to summarize and critically appraise research developing or validating instruments to assess patient-reported safety, efficacy and/or misuse in ongoing opioid therapy for chronic pain. Our search included the following datasets: OvidSP MEDLINE (1946 --August 2012), OvidSP PsycINFO (1967 – August 2012), Elsevier Scopus (1947 – August 2012), OvidSP HaPI (1985 -- August 2012) and EBSCO CINAHL (1981 – August 2012). Eligible studies were published in English and pertained to adult, non-surgical/interventional populations. Two authors independently assessed inclusion criteria. Each study was evaluated by two authors to assess the sources and content of items, types of psychometric tests, their results and quality of diagnostic accuracy testing, when applicable. Of 1874 citations found in the initial search, we identified 14 studies meeting our inclusion criteria, describing nine different instruments. Individual items were derived from surveys of content experts, literature reviews and adapted non-patient-reported items. Misuse-related items were most prevalent (60/144; 42%), followed by safety (47/144; 33%), with efficacy having the fewest items (17/144; 12%). The studies employed a wide variety of psychometric tests, with most demonstrating statistical significance, but several potential sources of bias and generalizability limitations were identified. Lack of testing in clinical practice limited assessment of feasibility. The dearth of safety and efficacy items and lack of testing in clinical practice demonstrates areas for further research.

Keywords: analgesics, opioid, chronic pain, tests, diagnostic, psychometrics, review, systematic

Introduction

The challenges facing patients and providers in managing ongoing opioid analgesic therapy for chronic pain are complex. Benefit of long-term opioid therapy, for which there are scant data to guide providers,[22] must be balanced against myriad potential undesired outcomes including safety concerns, ranging from mild toxicities to overdose and death [42]; inadequate efficacy, which may mean continued patient suffering and unwarranted exposure to toxicities; and misuse of these potent medications. To help patients and providers navigate these challenges and optimize therapy, experts advise a strategy of frequent re-assessment of safety, efficacy and misuse in patients on opioids to inform treatment decisions.[7; 39] To date, however, there is no widely-accepted instrument or protocol to facilitate this monitoring strategy.

The strategies for monitoring various aspects of opioid therapy can be divided into those that rely on patient report, for example asking patients about side effects and therapeutic effects, and those that do not, for example observing a patient for somnolence, performing urine drug testing or querying a prescription monitoring database for evidence of multiple prescribers. While the latter strategies are important for high quality clinical care, in this review, we solely focus on instruments that collect patient-reported data since non-patient reported measures have been recently reviewed elsewhere.[31; 37] Additionally, we recognize that patient report is the foundation of monitoring the impact of pain treatment [15] and acknowledge the increasing emphasis on patient reported outcomes in assessing quality of care.[6; 12] As such, the current study was designed to systematically review the psychometric development and testing of patient-reported instruments assessing safety, efficacy and misuse of opioids and, when possible, to assess the operating characteristics of these instruments compared to a reference standard assessment. This review addresses a void in the literature as previous reviews have included only instruments assessing risk of or current misuse.[8; 28; 41]

Methods

Identification of Studies

We identified studies by searching electronic databases, scanning bibliographies of included studies, contacting leaders in the field and searching consensus clinical guidelines for potentially relevant instruments missed in the initial search. The search strategy was applied to OvidSP MEDLINE (1946 to August, 2012), OvidSP PsycINFO (1967 to August, 2012), Elsevier Scopus (1947 to August, 2012), OvidSP HaPI (1985 to August, 2012) and EBSCO CINAHL (1981 to August, 2012) with the last search occurring on August 22, 2012. The full electronic search strategy for OvidSP MEDLINE is presented in Appendix 1.

We included studies that developed or validated an instrument designed to assess patient-reported safety, efficacy or misuse of opioids in ongoing therapy. We excluded studies not published in English; that involved non-human subjects; that did not study adults 18 and older; or that were related to perioperative or interventional opioid treatment since such clinical scenarios involve markedly different safety, efficacy and misuse considerations. Further, we excluded studies that were not related to opioid treatment for chronic pain; that did not study a domain of interest (i.e. safety, efficacy or misuse); or that did not provide data on development or validation. Additionally, we excluded studies of instruments assessing risk of safety, efficacy or misuse prior to opioid treatment and instruments employing non patient-reported items exclusively. We did not exclude any articles based on study design. Two authors (WB and EE) independently evaluated the abstract of each study and, when necessary, the full text, to determine inclusion; discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction

We developed a data extraction instrument based on models from other systematic reviews and standards in the field for psychometric and diagnostic instruments.[10; 11; 13; 14; 17; 21; 35; 43] Three data extractors with clinical and health services research backgrounds piloted the data extraction sheet using two randomly-chosen studies included in the systematic review. After the piloting phase, the research team met to discuss difficulties with the extraction instrument, to clarify questions prompted by the piloted studies, and to compare extracted data. This process helped refine the study aims, created consensus among the data extractors and prompted minor modifications to the data extraction instrument. Once the data extraction instrument was finalized, the two piloted studies were returned to the pool for re-review. Subsequently, after each pair of randomly assigned raters completed two extractions, the first author compared data extracted. Differences were presented to raters to resolve by consensus.

Extraction variables

The complete list of extraction variables and definitions is available in Appendix 2. Further detail on some of the extraction variables is provided below.

Source(s) and development of items

We compiled data on how items were identified or, when applicable, the process by which they were modified from other instruments or created de novo. One method of item development, assessment of response processes, defined as reviewing the actions or thought processes of respondents,[10] was also considered a test of construct validity (see below).

Categorization of items

We categorized the content area of each item based on whether it directly elicited information about the patient’s own experience taking opioids. Safety-related items covered adverse effects, side effects and toxicities; efficacy related items covered benefit of the medication in terms of, for example, pain intensity or functional status; and misuse-related items pertained to using the medication other than how it was prescribed including co-use of illicit substances and/or alcohol and more severe compulsive use characteristics of addiction. Items assessing content pertaining to limitations other than the patient’s current experience taking the medication--for example, a patient’s history of addiction, a patient’s family history of addiction or a patient’s anger or emotional lability--were categorized as ‘other’.

Assessment of study and instrument quality

We assessed quality of the studies and instruments across five criteria: (1) categories of psychometric testing performed across all studies of each instrument; (2) results of reliability and validity testing; (3) risk of bias; (4) generalizability to general medical practice settings; and (5) clinical utility. We evaluated the categories of psychometric testing—defined in Appendix II--by comparing testing done on each instrument to a checklist adapted from expert recommendations [10; 13; 14] including the following six categories of tests: (1) test-retest reliability; (2) validity testing based on content; (3) response processes; (4) internal structure (internal consistency, dimensionality); (5) relationship to other variables (responsive, discriminative, criterion, and predictive validity) and (6) diagnostic accuracy. We categorized results of the psychometric testing as “robust” if statistical analyses of all psychometric testing were significant and ”equivocal” if they were not.

We assessed risk of bias and generalizability using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) tool.[21; 43] The QUADAS-2 is designed to guide reviewers in evaluating risk of bias (categorized as ”low” or ”high”), and generalizability limitations, (categorized as ”no” or ”yes”) - with respect to patient selection, conduct and interpretation of the candidate test, conduct and interpretation of the reference standard and patient flow and timing. Our frame of reference for generalizability was to general medical settings where the majority of opioids are prescribed. Some studies did not employ tests of diagnostic accuracy or use a reference standard comparison related QUADAS-2 items were listed as ”not applicable” in those instances.

We assessed clinical utility based on whether the instrument had safety, efficacy and misuse-related items (yes or no); and whether it was demonstrated to be feasible in clinical practice; or, if feasibility was not tested, whether it was likely to be feasible in clinical practice, as judged by the reviewers (yes or no). Brief instruments that required limited scoring and were easily interpretable were considered feasible. Two yes answers equated to high clinical utility; fewer than 2 yes answers equated to equivocal clinical utility.

Results

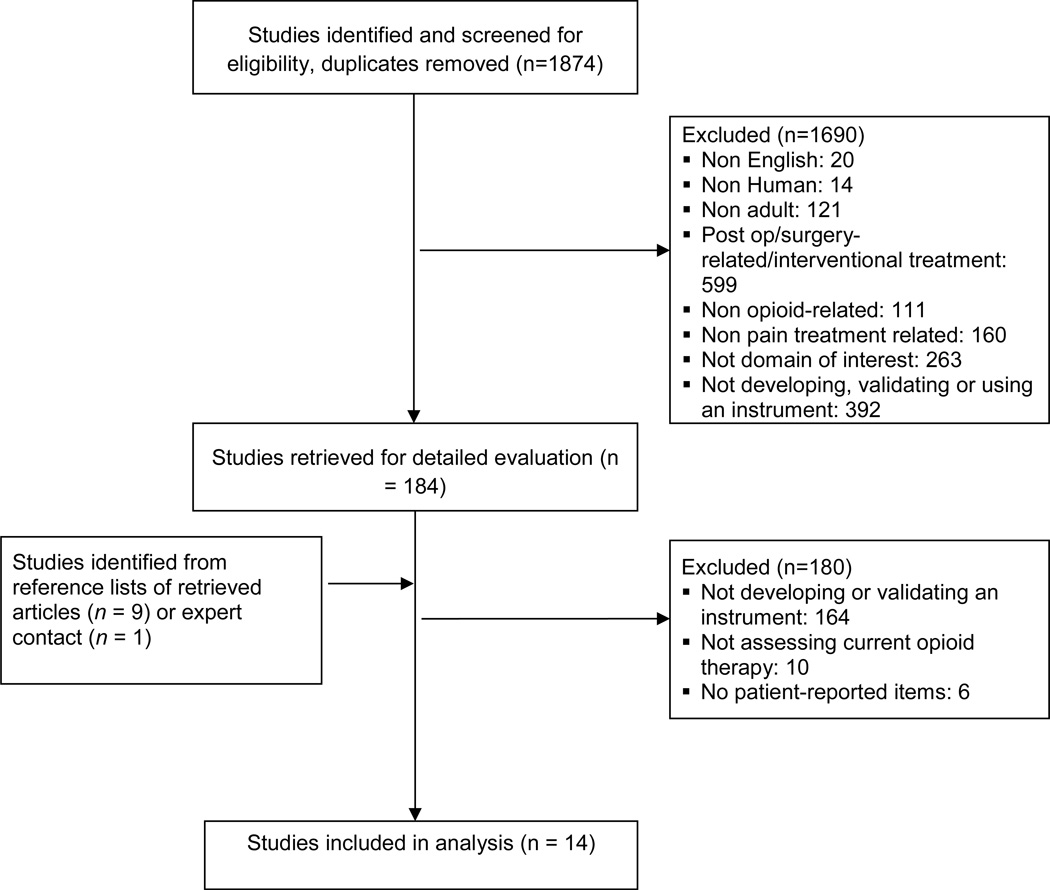

We identified 14 studies [1–5; 9; 18; 24; 27; 30; 32; 33; 36; 38] meeting the inclusion criteria describing the development or validation of 9 different instruments (Figure 1); four instruments were tested in more than one study. The kappa statistic for agreement on inclusion vs. exclusion was 0.92, indicating high inter-rater agreement.

Figure.

Study flow diagram

Study and instrument characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Included instruments, studies and characteristics of patients

| Instrument | Study/ies | Purpose | Participants and demographics |

Exclusion criteria |

Administration during testing |

Description of pain related disorders |

Description of opioid therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instruments assessing safety, efficacy and misuse | |||||||

| Prescribed Opioids Difficulties Scale (PODS) |

Banta-Green et al 2010 | Develop instrument to assess difficulties with chronic opioid therapy as perceived from patients’ perspectives, based on 2 expected domains: psychosocial problems attributed to opioids and concerns about control of opioid medications |

1144 patients on chronic opioids enrolled in Group Health for at least 1 year; age range 21–80; %female=61; %white=84; %employed=39 |

Cancer diagnosis |

Telephone survey, trained interviewer; time unpublished |

Most bothersome pain problem in past 3 months: back pain 29.6%; widespread/multiple 25.4%; leg 19.6%. Reporting 2+ pain problems in the past 6 months: 98.0%. |

Average daily dose in year prior (mg/d): 0–49 (33.8%); 50–99 (33.7%); ≥100 (32.5%). Most frequently used opioids in the past 3mo: long- acting morphine (24.7%); hydrocodone (20.2%); oxycodone (16.9%); long-acting oxycodone (16.1%); methadone (10.0%). |

| Sullivan et al 2010 | Assess psychosocial difficulties patients attribute to use of opioid medications using the PODS |

1144 patients on chronic opioids enrolled in Group Health for at least 1 year; age range 21–80; %female=63; %white=83; %employed=45 |

Cancer diagnosis |

Telephone survey, trained interviewer; time unpublished |

Most bothersome pain problem in past 6 months: back pain 28.9%; widespread/multiple 20.0; leg 24.5. Reporting 2+ pains in last 6 months: 98.3%. |

Average daily dose in year prior (mg/d): 0–49 (74.2%); 50–99 (15.0%); ≥100 (10.8%). Most frequently used opioids in past 3 months: hydrocodone combination (34.9%); oxycodone (21.6%); long-acting morphine (16.7%); long-acting oxycodone (8.5%); codeine combination (5.2%). |

|

| Pain Assessment and Document- ation Tool (PADT) |

Passik et al 2004 | Develop a charting tool focused on outcomes in pain treatment |

366 patients on opioids from both primary care and pain specialty; mean age not reported; %female=64; %white=84; %employed=29 |

None published | Clinician administered; alpha version (59 items) took 10–20 minutes to complete |

Not published | Not published |

| Instruments assessing two contents areas (safety and misuse or efficacy and misuse) | |||||||

| Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) |

Butler et al 2007 | Develop an assessment tool to monitor misuse of opioids among patients on chronic opioid therapy |

227 patients on opioids from 3 pain specialty practices; mean age=41; %female=62; %white=83; %employed=not published |

Cancer diagnosis Serious psychiatric impairment |

Patient self- administered; time unpublished |

Pain intensity 0–10, past 24 hours: worst 7.3 (SD = 2.1); least 4.5 (SD = 2.2); average 5.9 (SD = 1.8); current 5.8 (SD = 2.2). Pain interference (0–10): general activity 6.5 (SD = 2.6); mood 5.1 (SD = 2.7); walking 6.1 (SD = 3.0); normal work 7.2 (SD = 2.6); relations with others 4.0 (SD = 3.2); sleep 6.3 (SD = 3.1); enjoyment of life 6.2 (SD = 3.0). |

Years taking opioids: mean 5.7 (SD = 9.2; range 5 months-66 years) |

| Butler et al 2010 | Validate the COMM in a new population |

226 patients on opioids from 3 pain specialty practices; mean age=52; %female=48; %white=83; %employed=not published |

None published | Patient self- administered; time unpublished |

Pain intensity 0–10, past 24 hours: worst 7.0 (SD = 2.3); least 4.5 (SD = 2.4); average 5.9 (SD = 1.9); current 5.5 (SD = 2.3). Pain interference (0–10): general activity 5.9 (SD = 2.6); mood 4.6 (SD = 2.9); walking 5.9 (SD = 3.1); normal work 6.7 (SD = 2.9); relations with others 3.8 (SD = 3.1); sleep 5.9 (SD = 3.0); enjoyment of life 6.0 (SD = 3.1). |

Years taking opioids: mean 5.4 (SD=5.8; range 1 mo-38 years) |

|

| Meltzer etal 2010 | Validate the COMM in a primary care sample; Test COMM against measure of prescription drug use disorder |

238 patients on opioids from the primary care clinics of an urban, academic medical center; mean age=47; %female=56; %white=20; %employed=not published |

None published | Designed to be patient self- administered but may have been interviewer administered; time unpublished |

Chronic pain, defined as 3 months or greater based on chart review |

15% of the subjects received the equivalent of 20 tablets of 5 mg oxycodone in <2 fills; 12.6% received 21–60 tablets in ≤3 fills; 22.7% received 61–150 tablets in ≤3 fills; and 49.6% received >150 tablets or >3 fills of any amount (eg, 4 prescriptions of 20 tablets each). The majority in the last category received >6 fills. |

|

| Prescription Drug Use Question- naire – patient version (PDUQ-p) |

Compton et al 2008 | Adapt the Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire to be patient- administered; assess predictive validity of PDUQp |

135 patients on opioids in pain specialty setting; mean age=53; %female=6; race/ethnicity not reported; %employed=19 |

Current DSM-IV- based substance use disorder diagnosis |

Patient self- administered; time unpublished |

104 participants had a primary musculoskeletal pain problem, 26 neuropathic pain problem, 5 had multicategory or unclear pain problems. 75% reported pain was always present, 16% often present, remainder reported rare or variable pain. |

Not published |

| Banta- Green et al 2009 |

Assess psychometric properties of the PDUQp in different setting; examine factor structure of PDUQp and relationship to DSM- IV opioid abuse/ dependence diagnoses |

704 patients on chronic opioids, enrolled in Group Health for at least 3 years; mean age=55; %female=62; %white=89; %employed=40 |

Cancer diagnosis |

Telephone survey, trained interviewer; time unpublished |

Not published | Filled ≥10 opioid prescriptions (excluding emergency room visits) or filled ≥120 days’ supply of opioids and ≥ 6 prescriptions during 12- month period. |

|

| Modified Pain Medication Question- naire (mPMQ) |

Park et al 2010 |

Adapt the Pain Medication Questionnaire for geriatric population |

150 patients on opioids for at least a month from both primary care and pain specialty; mean age=73; %female=29; %white=51; %employed not reported |

Institutionalizati on |

Participants chose between self- administered and researcher administered; time unpublished |

Arthritis/joint problems (84.7%); back problems (76.0%); ] type II diabetes (38.0%); headaches (37.3%); dental problems (36.0%); heart disease (34.7%); cancer (22.7%); osteoporosis (19.3%), stroke (8.0%). Other disorders reported by ≤ 9 participants included fractures, fibromyalgia, and type I diabetes. |

Oxycodone plus acetaminophen (34.7%); oxycodone (26.7%); sustained-release morphine (13.3%); tramadol (12.7%); sustained release oxycodone (8.7%), and hydrocodone plus acetaminophen (8.0%). Other medications reported by ≤ 6 participants: propoxyphene, propoxyphene with acetaminophen, hydromorphone, fentanyl patches, and methadone. |

| Instruments assessing one content area (safety or misuse) | |||||||

| Prescription Opioid Misuse Index (POMI) |

Knisely etal 2008 | Assess a brief interview focused on prescription use behaviors |

74 patients on opioids; 40 from addiction treatment, 34 from pain specialty; mean age=38; % female=45; %white=95; %employed not reported |

None published | Trained interviewer; time unpublished |

Not published | All patients currently or recently taking OxyContin |

| Bowel Function Index (BFI) |

Rentz et al 2009 | Evaluate the psychometric characteristics of the BFI in patients with opioid-induced constipation |

985 patients on opioids; referral source not reported; mean age=57; % female=61; %white not reported; %employed not reported |

Current alcohol or drug abuse or acute medical illness |

Clinician administered; time unpublished |

All patients had moderate to severe chronic pain |

All patients were taking sustained release oxycodone per study protocol |

| Rentz et al 2011 |

Assess the psychometric properties of the BFI with respect to patient-reported outcomes in opioid- induced constipation |

131 patients on opioids; referral source not reported; mean age=64; % female=66; %white=99; %employed not reported |

Cancer; rheumatoid arthritis; significant structural abnormalities of GI tract; severe psychiatric co- morbidity |

Patient- administered; time unpublished |

All patients had chronic noncancer pain |

All patients were on around-the-clock opioids |

|

| Patient Assessment of Consti- pation Symptoms (PAC-SYM) |

Slappendel et al 2006 | Evaluate the reliabililty, validity and responsiveness of PAC-SYM in assessing opioid- induced constipation |

680 patients on opioids; referral source not reported; mean age=54; %female=61; %white not reported; %employed not reported |

Strong opioid treatment in the four weeks before the study; chest disease, renal dysfunction; skin diseases that might affect transdermal delivery; history of alcohol or substance abuse; another chronic pain disorder in addition to chronic low back pain; life- limiting illness |

Not reported | Cause of low back pain: Mechanical (83%); inflammatory (8%); post-surgical/trauma (39%); metabolic (1%); other (3%) |

All patients were on fentanyl transdermal reservoir or oral sustained-release morphine per study protocol |

| Bowel Function Diary (BF- Diary) |

Camilleri 2010 | Evaluate the psychometric properties of the BF- Diary for assessing opioid-induced constipation and qualify the BF-Diary for use in research |

238 patients on opioids; referral source not reported; mean age=54; % female=58; %white=not reported; %employed not reported |

treated with opioids during 14 days before baseline; history of constipation- related bowel dysfunction or opioid abuse; reported constipation at baseline |

Patient- administered via electronic device |

Osteoarthritis (68 %); low back pain (53 %) |

All patients were on opioids |

Detailed descriptions of all studies meeting inclusion criteria are provided in Table 1. Regarding the stated purpose of the instruments, one sought to assess safety, efficacy and misuse of prescribed opioids: the Pain Assessment and Documentation Tool (PADT) [30]; three aimed to assess one aspect of safety – opioid-induced constipation: the Bowel Function Index (BFI) [32; 33], the Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms (PAC-SYM) [36], and the Bowel Function Diary (BF-Diary) [5]; four explicitly targeted misuse: the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) [3; 4; 24]; the Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire-patient version (PDUQ-p) [1; 9]; the modified Pain Medication Questionnaire (mPMQ) [27] and the Prescription Opioid Misuse Index (POMI) [18]; and one aimed to assess patients’ perceived difficulties with opioid therapy: the Prescribed Opioid Difficulties Scale (PODS) [2; 38].

Characteristics of patients included in instrument development and validation (Table 1)

The sizes of the development or validation cohorts ranged from 74 to 1144 patients. Some studies recruited samples entirely from primary care, some entirely from pain specialty care and some from mixed primary care/pain specialty settings. Mean age of the cohorts ranged from 38 to 73; however, four studies did not publish a mean age and one study (mean age of 73) targeted geriatric patients.[27] The proportion of female participants ranged from 6% to 64%. Most of the study cohorts had a higher proportion of white patients than the U.S. population, except one study with a cohort that was 51% white [27] and another with a cohort that was 20% white.[24] In studies where employment status was published, the percentage employed (part or full time) ranged from 19 to 45%. In accordance with the inclusion criteria, the cohorts consisted of patients with chronic pain on long-term opioid therapy except for 40/74 of the participants in the POMI’s cohort in whom it was not clear whether pain existed [18]; pain-related diagnoses and/or assessments were reported in a wide variety of formats, except in three studies, where they were not described.[18; 24; 30] Six studies excluded patients with cancer;[1; 2; 4; 32; 36; 38] two studies excluded patients with ”serious psychiatric impairment;”[4; 32] and four studies excluded patients with a current DSM-IV-based substance use disorder diagnosis[9] or other indicator of current substance abuse.[5; 33; 36]

Characteristics of items within instruments (Table 2)

Table 2.

Description of items and instrument testing

| Instrument | Studies; total # items |

Source(s) and development of items |

Item Domain (number of items/percentage patient- reportable) |

Reliability and Validity Metrics and Results |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safety | Efficacy | Misuse | Other | ||||

| Instruments assessing safety, efficacy and misuse | |||||||

| Prescribed Opioids Difficulties Scale |

Banta-Green et al 2010; 16 |

|

8/100% | 1/100% | 7/100% | n/a | Content: 2 content experts/co-authors reviewed coverage of items. |

| Response processes: First author reviewed participants’ comments about items to inform modifications. | |||||||

| Internal consistency (2 subscales identified): Problems subscale: cronbach’s alpha >0.8; concerns subscale 0.70; total scale 0.87 (derivation) and 0.82 (derivation, recoded) and 0.87 (validation) and 0.81 (validation, recoded) | |||||||

| Dimensionality: Multiple exploratory factor analyses on derivation and validation split samples | |||||||

| Sullivan et al 2010; 16 | PODS (see Banta-Green et al 2010) | 8/100% | 1/100% | 7/100% | n/a | Criterion: PODS scores were compared to pain intensity, pain interference, depression symptoms (PHQ-8) and 2 chart- review measures of substance abuse → weak correlation with pain interference; strong correlation with PHQ-8. |

|

| Pain Assessment and Document- ation Tool |

Passik et al 2004; 42 |

|

12/100% | 12/42% | 17/0% | 1/0% (changes to treatment plan) |

Content (59 items): 6 experts reviewed items in alpha version → eliminated 18 items and added 1 |

| Internal consistency (1 section): Cronbach’s alpha=0.86 | |||||||

| Dimensionality (1 section): Exploratory factor analysis → all items loaded onto 1 factor | |||||||

| Instruments assessing two content areas (safety and misuse or efficacy and misuse) | |||||||

| Current Opioid Misuse Measure |

Butler et al 2007; 17 |

|

3/100% | 0/0 | 11/100% | 3/100% (anger, emotional lability) |

Test-retest (40 items): 55 participants took the alpha-version twice; intra-class correlation=0.87 (no significance testing) |

| Content (40 items): 22 experts reviewed the alpha-version; every item scored 2.4 or higher on 1–5 importance scale | |||||||

| Internal consistency (17 items): Cronbach’s alpha=0.96 | |||||||

| Dimensionality (40 items): 6 clusters identified using concept mapping | |||||||

| Criterion validity: Comparing COMM scores to criterion measure (ADBI) →Cohen’s D=1.25 | |||||||

| Diagnostic accuracy (17 items): Receiver-operator curves demonstrating true positive/false positive rates for each score on the Current Opioid Misuse Measure compared to Aberrant Drug Behavior Index (ADBI) → area under the curve=.81 | |||||||

| Butler et al 2010; 17 | COMM (see Butler et al 2007) |

3/100% | 0/0 | 11/100% | 3/100% (anger, emotional lability) |

Internal consistency: Cronbach’s alpha=0.83 |

|

| Diagnostic accuracy: Receiver-operator curve demonstrating true positive/false positive rates for each score on the COMM compared to Aberrant Drug Behavior Index (ADBI) → area under the curve=0.79 (p<0.001) | |||||||

| Meltzer et al 2010; 16 |

COMM with 1 item different |

3/100% | 0/0 | 10/100% | 3/100% (anger, emotional lability) |

Diagnostic accuracy: Receiver-operator curve demonstrating true positive/false positive rates for each score on the Current Opioid Misuse Measure compared to CIDI interview-ascertained prescription drug use disorder → area under the curve = 0.84 (95% confidence interval, 0.76, 0.91). |

|

| Prescription Drug Use Question- naire – patient version |

Compton etal 2008; 31 | PDUQ, with redundant or low-performing items removed |

0/0 | 2/100% | 15/100% | 14/100% (other treatments tried, family history of addiction, anger towards doctors, personal history of addiction, family members assist in care) |

Test-retest: Baseline to four months (r=0.67, p<0.001), eight months (r=0.61, p<0.001) and 12 months (r=0.40, p=0.001) |

| Criterion validity: Comparison of PDUQp to PDUQ scores → r=0.64, p<0.001 at 4 months. | |||||||

| Predictive validity: Baseline PDUQp score was significantly associated with odds of medication agreement violation-related discharge from the practice. | |||||||

| Diagnostic accuracy: Using a cutoff score of 10, sensitivity of PDUQp for medication agreement violation-related discharge from practice=51.4%, specificity 59.8%; for opioid specific problem- related discharge: sensitivity=66.7%, specificity=59.7%. | |||||||

|

Banta-Green et al 2009; 25 |

PDUQp, modified for phone interviewing purposes and based on factor analysis |

0/0 | 2/100% | 15/100% | 8/100% (other treatments tried, family history of addiction, anger towards doctors, personal history of addiction, family members assist in care) |

Content (25 items): Study team and external experts removed 6 items because content was poor fit with studied clinical population or endorsement levels were too high or low. |

|

| Internal consistency (25 items): Cronbach’s alpha=0.56 | |||||||

| Dimensionality (19 items): Factor analysis of 19 items from PDUQ revealed 3 factors and 4 items that did not load on these 3. | |||||||

| Criterion (15 items): Factor analysis comparing CIDI DSM-IV abuse/dependence criteria and 15 items from PDUQ revealed low concordance. | |||||||

| Pain Medication Question- naire, modified |

Park et al 2010; 7 |

Pain Medication Questionnaire |

0/100% | 2/100% | 4/100% | 1/100% (find it helpful to call doctor to discuss pain) |

Internal consistency: Cronbach’s alpha=0.73 |

| Dimensionality: Exploratory factor analysis revealed a 2 factor solution with 7 items (reduced from 26) having the highest factor loading belonging to either of the 2 factors. | |||||||

| Instruments assessing one content area (safety or misuse) | |||||||

| Prescription Opioid Misuse Index |

Knisely et al 2008; 6 | Frequently used questions in investigators’ clinical practice |

0/0 | 0/0 | 6/100% | n/a | Internal consistency: Cronbach’s alpha=0.85; principal component analysis → eliminated 2 items |

| Diagnostic accuracy: Receiver-operator curve demonstrating true positive/false positive rates for each score on the Prescription Opioid Misuse Index compared to DSM-IV checklist-ascertained opiate addiction → area under the curve=.89 (p<.001). | |||||||

| Bowel Function Index (BFI) |

Rentz et al 2009; 3 | Established criteria of known assessment tools for opioid induced constipation |

3/3 | 0/0 | 0/0 | n/a | Test-retest: In a sub-sample, no significant difference in BFI score at 2 time points where stability was expected |

| Internal consistency: Cronbach’s alpha=>0.7 | |||||||

| Discriminative: Each item significantly correlated with degrees of constipation as established by diary entries. | |||||||

| Responsive: BFI scores improved in a statistically significant trend with increasing doses of naloxone. | |||||||

| Rentz et al 2011; 3 |

BFI (see Rentz etal 2009) | 3/3 | 0/0 | 0/0 | n/a | Internal consistency: Cronbach’s alpha for total BFI score=0.86; inter-item and item-total correlations were all statistically significant |

|

| Discriminative: BFI item and total scores significantly discriminated between three constipation severity categories based on clinical interview. | |||||||

| Criterion: Correlations between the BFI and Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms (PAC-SYM) were in the low-moderate to high range and all were significant (r=0.26 to 0.66; p<0.01 to 0.0001). | |||||||

| Patient Assessment of Consti- pation Symptoms (PAC-SYM) |

Slappendel et al 2006; 12 |

PAC-SYM validated in non- opioid-taking population |

12/12 | 0/0 | 0/0 | n/a | Internal consistency: Cronbach’s alpha for three subsections=>0.7 Each item of PAC-SYM correlated with its own domain (Pearson correlation range=0.57–0.71) |

| Dimensionality: Three domains were moderately inter-correlated, allowing combining domains into a global score | |||||||

| Discriminative: PAC-SYM scores correlated with presence/absence of constipation based on clinical score (one-way ANOVA test of differences F= 114; p < 0.0001.) | |||||||

| Predictive: Global score’s correlation with dropping out due to constipation reasons and/or treatment switches due to a drug-related adverse constipation event was low. | |||||||

| Bowel Function Diary (BF- Diary) |

Camilleri et al 2010; 10 |

|

9/9 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 1/1 (list of laxatives used) |

Test-retest: Intra-class correlation >0.71 for all items except stool consistency (0.52) comparing 2 time points where stability was expected. |

| Content: Survey of experts to review items. | |||||||

| Response processes: Assessed patient comprehension of items during development. | |||||||

| Dimensionality: Factor analysis revealed a 3-factor solution. | |||||||

| Discriminative: All items were correlated with single-item self-assessment of constipation status. | |||||||

The sources and development of items varied widely but surveys of content experts, literature reviews and adaptation of non-patient-reported items were used most frequently. Patient feedback was used in two studies to modify items.[2; 5] Misuse-related items were the most prevalent (42%), followed by safety (33%), with efficacy having the fewest items (12%). Most of the items in all the instruments were patient-reported; however, the PADT contained 5/12 efficacy-related items and 17/17 misuse-related items that were not patient-reported.[30]

Instrument reliability and validity testing and results (Table 2)

The studies employed a range of tests within the six psychometric testing categories. Reliability testing was performed on four instruments, with the COMM (intra-class correlation=0.87), the PDUQ-p (r=0.67, p<0.001), the BFI [33] and the BF-Diary [5] demonstrating good test re-test reliability.(24, 27) Content validity assessment, performed in five instruments,[2; 4; 5; 9; 29] employed experts ranging from office staff to physician subject matter experts. Validity based on response processes was tested in the PODS [2] and the BF-Diary [5] in which items were modified based on patient feedback. Validity testing based on internal structure was used on all the instruments, with internal consistency ranging from Cronbach’s alpha 0.56 [1] – 0.96 [4] and dimensionality tested in a variety of methods of factor analysis. Validity testing based on relationship to other variables was performed in three instruments, with criterion validity established for the PODS’ relationship to the Patient Health Questionnaire, a self-reported measure of depressive symptoms (r = 0.317, p < 0.001); [38] the COMM’s relationship to the Aberrant Drug Behavior Index (Cohen’s D=1.25); [4] the PDUQ-p’s relationship to the original Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire (r=0.64, p<0.001); [9] and the BFI’s relationship to the PAC-SYM.[32] However, criterion validity was not established for the PDUQ-p’s relationship to the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) for lifetime opioid abuse and dependence as factor analysis of the CIDI compared to the PDUQ-p revealed low concordance.[1] Discriminative validity was established across a range of scores on the BFI compared to in-depth clinical interview;[32; 33] scores on the PAC-SYM compared to a clinical constipation score;[36] and correlation between items on the BF-Diary compared to constipation status.[5] Predictive validity was tested and established in the PDUQ-p as baseline PDUQ-p score was significantly associated with odds of medication agreement violation-related discharge from the practice.[9] However, predictive validity was not established for the PAC-SYM as its global score’s correlation with drop out or treatment switches due to constipation was low.[36] Responsive validity was tested in the BFI, where it demonstrated significantly improved scores with increasing doses of the opioid antagonist naloxone.[33] Tests of diagnostic accuracy were performed on three instruments. In two separate studies, the COMM demonstrated good accuracy compared to the Aberrant Drug Behavior Index (area under the curve=0.81, p<0.05) [3] and DSM-IV prescription drug use disorder (area under the curve = 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.76, 0.91).[24] The PDUQ-p demonstrated modest accuracy compared to chart reviews ascertaining medication agreement violation-related discharge from practice (sensitivity=51.4%, specificity 59.8%) and opioid specific problem-related discharge (sensitivity=66.7%, specificity=59.7%).[9] The POMI was accurate when compared to a DSM-IV checklist-ascertained diagnosis of opioid dependence (area under the curve=.89, p<.001) [18].

QUADAS-informed quality assessment (Table 3)

Table 3.

QUADAS-2 informed quality assessment

| Risk of Bias | Generalizability Limitations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | Study/ies | Patient Selection |

Candidate Test |

Reference Standard |

Flow and Timing |

Patient Selection |

Candidate Test |

Reference Standard |

| Prescribed Opioid Difficulties Scale |

Banta- Green et al 2010 |

Low | Low | n/a | High | No | No | n/a |

| Sullivan et al 2010 | Low | Low | n/a | High | No | No | n/a | |

| Pain Assessment and Documentation Tool |

Passik et al 2004 | High | High | n/a | n/a | No | Yes | n/a |

| Current Opioid Misuse Measure |

Butler et al 2007 | Low | Low | Low | High | No | No | No |

| Butler et al 2010 | Low | Low | Low | High | No | No | No | |

| Meltzer et al 2010 |

Low | Low | Low | High | No | No | No | |

| Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire- patient version |

Compton etal 2008 | High | Low | Low | High | Yes | No | No |

| Banta- Green et al 2009 |

Low | Low | n/a | High | No | No | n/a | |

| Pain Medication Questionnaire, modified |

Park et al 2010 | Low | Low | n/a | n/a | No | No | n/a |

| Prescription Opioid Misuse Index |

Knisely et al 2008 | High | Low | Low | High | Yes | No | No |

| Bowel Function Index (BFI) |

Rentz et al 2009 | High | Low | n/a | High | No | No | n/a |

| Rentz et al 2011 |

High | Low | n/a | High | No | No | n/a | |

| Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms (PAC-SYM) |

Slappendel et al 2006 | High | Low | n/a | High | No | No | n/a |

| Bowel Function Diary (BF-Diary) |

Camilleri et al 2010 |

Low | Low | n/a | High | No | Yes | n/a |

With respect to risk of bias in patient selection, all except five of the studies were low risk as they employed a consecutive or random sample selection procedure and appropriate exclusion criteria. In the study of the POMI,[18] it was not clear how patients were selected; thus, risk of bias was considered high. Patient selection in the study of the PADT [29] and one study of the BFI [32] were considered to be at high risk of bias since a convenience sample of patients was used. Patient selection in one study of the PDUQ-p was considered to be at high risk of bias because patients with current substance use disorders were excluded.[9] Patient selection in the other study of the BFI [33] and the PAC-SYM [36] were considered to be at high risk of bias since participants were recruited from pharmaceutical company-sponsored clinical trials, which typically contain healthier individuals. With regard to the conduct or interpretation of the candidate test, all but one study was rated low risk for bias. Specifically, the PADT contained some items that were non-specific prompts (e.g. ”Increased dose without authorization”) requiring providers to use their own syntax, thus introducing variability and bias in conduct.[30]

Since nine of the studies [1; 2; 5; 27; 30; 32; 33; 36; 38] did not use a reference standard instrument to which to compare the candidate instrument, risk of bias in the conduct or interpretation of the reference standard could not be assessed. Five studies that did employ reference standard testing were low risk for bias since their conduct was standardized and clearly described.[3; 4; 9; 18; 24] In terms of patient flow and timing, all studies using a comparison test (whether reference standard or not) were rated high risk of bias since either the order or timing of assessments was not described.

Exclusion of patients with current substance use disorder was considered a generalizability limitation related to patient selection in the PDUQ-p;[9] whereas the POMI’s inclusion of over half its sample of ‘known opioid abusers’ [18] was considered a generalizability limitation. The PADT was assessed as having five efficacy-related and 17 misuse-related, non patient-reportable items, which was considered to be a generalizability limitation related to its conduct. Designed as a research instrument, the BF-Diary used an electronic platform requiring patients to carry a hand-held device and record answers after each bowel movement.[5] These factors were considered to be generalizability limitations. There was no generalizability limitation identified in the five reference standard instruments used and the target conditions they defined.[3; 4; 9; 18; 24]

All instruments were rated as having equivocal clinical utility. Some did not contain items from all content areas (COMM, PDUQ-p, mPMQ, POMI, BFI, PAC-SYM, BF-Diary); and/or were too long to be feasible in routine clinical practice, especially in general medical settings where multiple chronic diseases compete for patient and provider time and attention.[26] At 16 items, the PODS was borderline feasible; however, its administration by trained interviewers would limit its implementation in clinical practice.

Discussion

To monitor patients and make informed, patient-centered clinical decisions, providers need well-validated and feasible instruments for measuring patient-reported safety, efficacy and misuse of opioids. Our systematic review of the published literature identified 14 studies developing or validating nine instruments targeting patient-reported safety, efficacy and misuse. A shortcoming of all the instruments was that none had been tested in clinical practice, suggesting a need for further instrument development and validation. As such, important questions remain unanswered, specifically: what is the feasibility and acceptability of use of these instruments for patients and providers? Do these instruments accurately and consistently identify safety, efficacy and misuse limitations in clinical practice? And, perhaps the most important question that can only be answered through clinical trials: Does use of these instruments improve clinical outcomes?[34] The few studies using tests of diagnostic accuracy limits utility but may also be explained by, in some cases, the absence of a suitable reference standard to which to compare the instrument or, in others, that the instrument was designed more for documentation rather than diagnostic purposes.

With regard to feasibility, the main limitation was the length and respondent burden of the available instruments. As most opioid therapy is prescribed in general medical settings, monitoring must be brief to account for the reality of competing demands.[19] Several of the reviewed instruments were developed and validated in referral-based settings or for research purposes where time constraints may be less of a concern, which may explain in part why brevity was not a central focus. Shorter versions of the PODS and COMM could be studied to see if accuracy is preserved with reduced respondent burden. Furthermore, the PODS was interviewer-administered in its studies; demonstration of its feasibility as a patient-administered instrument would enhance its clinical utility. Another limitation related to feasibility that should be addressed in future instrument development is designing assessments that directly guide decision-making. Busy clinicians need to have a clear sense of the next steps informed by the assessment.

Our review highlighted a systematic weakness of the instruments with respect to testing patient comprehension of items. If an assessment is designed for patient-report, then establishment of patient comprehension of items – by testing the items via patient administration and then using response processes to guide modification – is critical to ensure construct validity.[10] One study used response processes,[2] mentioned briefly, and one study used this technique in an assessment designed primarily for research.[5] More thorough response processes in the pilot testing of items would add to the rigor of future instrument development. We identified significant gaps in the content covered by available instruments as another shortcoming. In terms of safety-related limitations, of a published list of seven clinically-relevant side effects of opioids (sedation, nausea/vomiting, delirium, myoclonus, pruritus, respiratory depression, constipation),[23] only five were assessed in any of the instruments. Secondary data analyses to determine frequency and scope of side effects, perhaps using novel methods such as natural language processing, and qualitative work to further determine what symptoms patients find distressing would likely lead to better accuracy. Beyond coverage of side effects, quantification of their severity and impact on the patient would further inform clinical decision-making.

Efficacy-related items were the fewest in number across instruments, possibly reflecting a belief that lack of efficacy is either (a) not as important as identifying safety or misuse limitations or (b) something patients will discuss without prompting or (c) already incorporated through the use of standardized measures like the numerical pain rating scale. However, lack of efficacy exposes patients to risk needlessly. Furthermore, data suggest that patients do not reliably discuss lack of efficacy with providers and may simply hoard medications or not fill prescriptions,[20] each of which carries its own implications for low quality of care. Consensus is building around the use of specific, mutually agreed-upon functional goals between patient and provider as benchmarks for efficacy [7; 25] but how to incorporate such goals into routine screening has not been studied. Brief measures studied in pain care broadly, such as the three-item PEG [19] or global assessment of benefit [40] may prove well-suited for opioid-specific use.

Nearly half of the items developed and validated in these instruments were related to opioid misuse. While this content area is important to both patient and public health, the value of patient-report may be compromised if patients perceive that opioid therapy may be discontinued if they provide truthful information about misuse.[16] Objective determinations such as urine drug testing, querying prescription monitoring databases, and documenting emergency department visits and early refill requests through electronic health records have the potential to augment patient-reported items in these instruments. Furthermore, if the sole target of assessment is misuse, as was the case with the COMM (though we identified 3 items related to safety), the time spent focusing on this may come at the expense of equally important assessments of safety and efficacy. An aspect of misuse that can only be captured through patient-reported items is the patient’s perception of their use as potentially unhealthy or addictive, which was the intent of three items of the PODS.[2] A combination of objective misuse measures and the patient’s perception of unhealthy or addictive use holds promise in improving accuracy and efficiency of assessment.

This systemic review has limitations. First, our search may have missed qualifying published instruments, especially if not published in English. To address this concern we queried experts, a large number of electronic databases, and searched the bibliographies of relevant literature. Second, we were not able to evaluate the utility of these instruments in assessing outcomes aside from safety, efficacy, or misuse of opioids or their use of non-patient-reported items.

Despite these limitations, this work adds to the existing literature by describing the breadth of work in the field and identifying opportunities for research to address important clinical needs. We found 14 studies describing the development and/or validation of nine instruments designed to assess patient-reported safety, efficacy and misuse of opioids during treatment of chronic pain. The dearth of safety and efficacy-related items and lack of testing in clinical practice demonstrates the need for further research.

Supplementary Material

Table 4.

Summary of quality assessments by instrument

| Instrument | Psychometric categories tested |

Statistical significance of testing |

Risk of bias in conduct/ interpretation |

Generalizability limitations |

Clinical utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PODS | 4 | Robust | Low | None | Equivocal |

| PADT | 2 | Equivocal | High | Conduct of instrument | Equivocal |

| COMM | 5 | Robust | Low | None | Equivocal |

| PDUQ-p | 5 | Equivocal | Low | Patient selection | Equivocal |

| mPMQ | 1 | Robust | Low | None | Equivocal |

| POMI | 2 | Robust | High | Patient selection | Equivocal |

| BFI | 3 | Robust | Low | Patient selection | Equivocal |

| PAC-SYM | 3 | Equivocal | Low | Patient selection | Equivocal |

| BF-Diary | 4 | Robust | Low | Conduct of instrument | Equivocal |

Summary.

Systematic review of the literature identified 14 studies of 9 instruments assessing patientreported safety, efficacy or misuse of current opioid therapy for chronic pain, of which none had been tested in clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Becker was supported by a Veterans Health Administration Health Services Research & Development Career Development Award (08-276); Dr. Fraenkel was supported by NIAMS K24 AR060231-01; Dr. Kerns was supported by VA Health Services Research and Development Research Enhancement Award Program (REA 08-266); Dr. Fiellin was supported by NIDA R01-DA020576-01A1 and NIAAA U01-AA020795-01. The authors report no conflict of interest related to the study. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Banta-Green CJ, Merrill JO, Doyle SR, Boudreau DM, Calsyn DA. Measurement of opioid problems among chronic pain patients in a general medical population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104(1–2):43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banta-Green CJ, Von Korff M, Sullivan MD, Merrill JO, Doyle SR, Saunders K. The prescribed opioids difficulties scale: a patient-centered assessment of problems and concerns. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(6):489–497. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181e103d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fanciullo GJ, Jamison RN. Cross validation of the current opioid misuse measure to monitor chronic pain patients on opioid therapy. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(9):770–776. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181f195ba. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler SF, Budman SH, Fernandez KC, Houle B, Benoit C, Katz N, Jamison RN. Development and validation of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure. Pain. 2007;130(1–2):144–156. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camilleri M, Rothman M, Ho KF, Etropolski M. Validation of a bowel function diary for assessing opioid-induced constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(3):497–506. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, Gershon R, Cook K, Reeve B, Ader D, Fries JF, Bruce B, Rose M, Group PC. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, Adler JA, Ballantyne JC, Davies P, Donovan MI, Fishbain DA, Foley KM, Fudin J, Gilson AM, Kelter A, Mauskop A, O'Connor PG, Passik SD, Pasternak GW, Portenoy RK, Rich BA, Roberts RG, Todd KH, Miaskowski C. American Pain Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines P. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10(2):113–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, Miaskowski C, Passik SD, Portenoy RK. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: prediction and identification of aberrant drug-related behaviors: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society and American Academy of Pain Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Pain. 2009;10(2):131–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Compton PA, Wu SM, Schieffer B, Pham Q, Naliboff BD. Introduction of a Self-Report Version of the Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire and Relationship to Medication Agreement Noncompliance. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2008;36(4):383–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook DA, Beckman TJ. Current concepts in validity and reliability for psychometric instruments: theory and application. Am J Med. 2006;119(2):e167–116. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.10.036. 166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devine EB, Hakim Z, Green J. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome instruments measuring sleep dysfunction in adults. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23(9):889–912. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200523090-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeWalt D, Revicki D. Importance of Patient-Reported Outcomes for Quality Improvement. National Quality Measures Clearinghouse. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downing SM. Validity: on meaningful interpretation of assessment data. Med Educ. 2003;37(9):830–837. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Downing SM. Reliability: on the reproducibility of assessment data. Med Educ. 2004;38(9):1006–1012. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Katz NP, Kerns RD, Stucki G, Allen RR, Bellamy N, Carr DB, Chandler J, Cowan P, Dionne R, Galer BS, Hertz S, Jadad AR, Kramer LD, Manning DC, Martin S, McCormick CG, McDermott MP, McGrath P, Quessy S, Rappaport BA, Robbins W, Robinson JP, Rothman M, Royal MA, Simon L, Stauffer JW, Stein W, Tollett J, Wernicke J, Witter J. Immpact. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113(1–2):9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012. [see comment]. [Review] [88 refs] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fishbain DA, Cutler R, Rosomoff H, Rosomoff R. Validity of self-reported drug use in chronic pain patients. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 1999;15(3) doi: 10.1097/00002508-199909000-00005. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kearney RS, Achten J, Lamb SE, Plant C, Costa ML. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures used to assess Achilles tendon rupture management: What's being used and should we be using it? British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2011 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knisely JS, Wunsch MJ, Cropsey KL, Campbell ED. Prescription Opioid Misuse Index: a brief questionnaire to assess misuse. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35(4):380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, Damush TM, Wu J, Sutherland JM, Asch SM, Kroenke K. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(6):733–738. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0981-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis ET, Combs A, Trafton JA. Reasons for Under-Use of Prescribed Opioid Medications by Patients in Pain. Pain Medicine. 2010;11(6):861–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mann R, Hewitt CE, Gilbody SM. Assessing the quality of diagnostic studies using psychometric instruments: applying QUADAS. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(4):300–307. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0440-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martell BA, O'Connor PG, Kerns RD, Becker WC, Morales KH, Kosten TR, Fiellin DA. Systematic review: opioid treatment for chronic back pain: prevalence, efficacy, and association with addiction. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(2):116–127. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-2-200701160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNicol E, Horowicz-Mehler N, Fisk RA, Bennett K, Gialeli-Goudas M, Chew PW, Lau J, Carr D, Americal Pain S. Management of opioid side effects in cancer-related and chronic noncancer pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2003;4(5):231–256. doi: 10.1016/s1526-5900(03)00556-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meltzer EC, Rybin D, Saitz R, Samet JH, Schwartz SL, Butler SF, Liebschutz JM. Identifying prescription opioid use disorder in primary care: diagnostic characteristics of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) Pain. 152(2):397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nicolaidis C. Police Officer, Deal-Maker, or Health Care Provider? Moving to a Patient-Centered Framework for Chronic Opioid Management. Pain Medicine. 2011;12(6):890–897. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostbye T, Yarnall KSH, Krause KM, Pollak KI, Gradison M, Michener JL. Is there time for management of patients with chronic diseases in primary care? Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):209–214. doi: 10.1370/afm.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park J, Clement R, Lavin R. Factor structure of pain medication questionnaire in community-dwelling older adults with chronic pain. Pain pract. 2011;11(4):314–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Passik SD, Kirsh KL, Casper D. Addiction-Related Assessment Tools and Pain Management: Instruments for Screening, Treatment Planning, and Monitoring Compliance. Pain Med. 2008;9:S145–S166. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Passik SD, Kirsh KL, Whitcomb L, Portenoy RK, Katz NP, Kleinman L, Dodd SL, Schein JR. A new tool to assess and document pain outcomes in chronic pain patients receiving opioid therapy. Clinical Therapeutics. 2004;26(4):552–561. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Passik SD, Kirsh KL, Whitcomb L, Portenoy RK, Katz NP, Kleinman L, Dodd SL, Schien JR. A New Tool to Assess and Document Pain Outcomes in Chronic Pain Patients Receiving Opioid Therapy. Clinical Therapeutics: The International Peer-Reviewed Journal of Drug Therapy. 2004;26(4):552–561. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reifler LM, Droz D, Bailey JE, Schnoll SH, Fant R, Dart RC, Bucher Bartelson B. Do Prescription Monitoring Programs Impact State Trends in Opioid Abuse/Misuse? Pain Medicine. 2012;13(3):434–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rentz AM, van Hanswijck de Jonge P, Leyendecker P, Hopp M. Observational, nonintervention, multicenter study for validation of the Bowel Function Index for constipation in European countries. Current Medical Research & Opinion. 27(1):35–44. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.535270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rentz AM, Yu R, Muller-Lissner S, Leyendecker P. Validation of the Bowel Function Index to detect clinically meaningful changes in opioid-induced constipation. J Med Econ. 2009;12(4):371–383. doi: 10.3111/13696990903430481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sackett DL, Haynes RB. The architecture of diagnostic research. Bmj. 2002;324(7336):539–541. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7336.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaneyfelt T, Baum KD, Bell D, Feldstein D, Houston TK, Kaatz S, Whelan C, Green M. Instruments for evaluating education in evidence-based practice: a systematic review. Jama. 2006;296(9):1116–1127. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slappendel R, Simpson K, Dubois D, Keininger DL. Validation of the PAC-SYM questionnaire for opioid-induced constipation in patients with chronic low back pain. European Journal of Pain. 2006;10(3):209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Starrels JL, Becker WC, Alford DP, Kapoor A, Williams AR, Turner BJ. Systematic review: Treatment agreements and urine drug testing to reduce opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(11):712–720. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sullivan MD, Von Korff M, Banta-Green C, Merrill JO, Saunders K. Problems and concerns of patients receiving chronic opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2010;149(2):345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Management for Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain Working Group. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain, Vol. 2.0: Office of Quality and Performance. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Burke LB, Gershon R, Rothman M, Scott J, Allen RR, Atkinson JH, Chandler J, Cleeland C, Cowan P, Dimitrova R, Dionne R, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Hertz S, Jadad AR, Jensen MP, Kellstein D, Kerns RD, Manning DC, Martin S, Max MB, McDermott MP, McGrath P, Moulin DE, Nurmikko T, Quessy S, Raja S, Rappaport BA, Rauschkolb C, Robinson JP, Royal MA, Simon L, Stauffer JW, Stucki G, Tollett J, von Stein T, Wallace MS, Wernicke J, White RE, Williams AC, Witter J, Wyrwich KW. Initiative on Methods MaPAiCT. Developing patient-reported outcome measures for pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2006;125(3):208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Turk DC, Swanson KS, Gatchel RJ. Predicting Opioid Misuse by Chronic Pain Patients: A Systematic Review and Literature Synthesis. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2008;24(6):497–508. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31816b1070. 410.1097/AJP.1090b1013e31816b31070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warner M, Chen LH, Makuc DM. Increase in fatal poisonings involving opioid analgesics in the United States, 1999–2006. NCHS data brief. 2009;22:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, Leeflang MMG, Sterne JAC, Bossuyt PMM. Group Q-. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.