Abstract

Fission yeast cells reject actin subunits tagged with a fluorescent protein from the cytokinetic contractile ring, so cytokinesis fails and the cells die when the native actin gene is replaced by GFP–actin. The lack of a fluorescent actin probe has prevented a detailed study of actin filament dynamics in contractile rings, and left open questions regarding the mechanism of cytokinesis. To incorporate fluorescent actin into the contractile ring to study its dynamics, we introduced the coding sequence for a tetracysteine motif (FLNCCPGCCMEP) at 10 locations in the fission yeast actin gene and expressed the mutant proteins from the native actin locus in diploid cells with wild-type actin on the other chromosome. We labeled these tagged actins inside live cells with the FlAsH reagent. Cells incorporated some of these labeled actins into actin patches at sites of endocytosis, where Arp2/3 complex nucleates all of the actin filaments. However, the cells did not incorporate any of the FlAsH-actins into the contractile ring. Therefore, formin Cdc12p rejects actin subunits with a tag of ~2 kDa, illustrating the stringent structural requirements for this for-min to promote the elongation of actin filament barbed ends as it moves processively along the end of a growing filament.

Keywords: Actin, Cytokinesis, Fission yeast, Formin, FH2, Tetracysteine

1. Introduction

Formins are a family of homodimeric proteins, each comprising two conserved domains in addition to more variable regulatory elements (Goode and Eck, 2007; Paul and Pollard, 2009b). Formin homology 2 (FH2) domains are composed of alpha-helices and connected head-to-tail to the partner FH2 domain by flexible linkers (Xu et al., 2004). These linkers can stretch enough for the FH2 dimer to wrap around an actin filament (Otomo et al., 2005), with a higher affinity for the barbed end than any other region of the filament. Formin homology 1 (FH1) domains are flexible polypeptides containing 2–12 polyproline sequences that bind profilin–actin complexes (Chang et al., 1997). Diffusion of the FH1 domains brings profilin–actin into contact with the barbed end (Kovar et al., 2006; Paul and Pollard, 2008), so that the complex can bind to the filament, followed by rapid dissociation of the profilin. The rate limiting step of formin mediated assembly of actin filaments is profilin–actin binding to the multiple FH1 sites, followed by the rapid transfer of actin onto the barbed end at a rate >1000 s−1 (Paul and Pollard, 2009a). As each new actin subunit adds to the barbed end, the formin steps reliably onto the new subunit, so formins move processively along growing barbed ends as more than 10,000 subunits are incorporated (Kovar et al., 2006; Paul and Pollard, 2008).

We are particularly interested in formin Cdc12p, which assembles actin filaments for the actomyosin contractile ring during cytokinesis in fission yeast. Fission yeast Schizosacchromyces pombe, is an excellent model organism to study the actin cytoskeleton, because powerful genetics, biochemistry and quantitative microscopy are available (for review see (Pollard and Wu, 2010)). These yeast cells have three structures composed of actin filaments: actin patches at sites of clathrin-mediated endocytosis, contractile rings for cytokinesis and actin cables for intracellular transport (for review, see (Kovar et al., 2011)). Genetics experiments showed that distinct proteins nucleate the actin filaments for these three structures: Arp2/3 complex nucleates filaments in actin patches (Morrell et al., 1999); formin Cdc12p nucleates filaments for the contractile ring (Chang et al., 1997); and formin For3p nucleates filaments for interphase cables (Feierbach and Chang, 2001). Deletion or temperature sensitive mutations of any of these actin nucleators leads to defects specifically in one type of actin structure but not the others. Each of these three nucleators localizes to distinct sites appropriate for the filaments they form in cells.

Although we know a great deal about the molecular components and assembly mechanism of contractile rings (Vavylonis et al., 2008; Wu and Pollard, 2005; Wu et al., 2003), we still know very little about the dynamics of actin filaments during the assembly and disassembly of the rings. This information would greatly enhance our understanding of the mechanism of cytokinesis. However, such an effort had been hampered by the lack of a fluorescence probe of actin filaments. Formins (Bni1, mDia1, mDia2, Cdc12p) incorporate actin subunits labeled with Oregon green (molecular weight 463) on cys374 or Alexa green (molecular weight 643) on a lysine side chain into actin filaments in biochemical assays (Kovar and Pollard, 2004). However, actin with an N-terminal fluorescent protein tag does not incorporate into the actin filaments of the contractile ring in fission yeast (Wu and Pollard, 2005). Since these actin filaments are essential for cell division, replacement of the native actin gene with a gene encoding a fusion of a fluorescent protein and actin results in the failure of cytokinesis and the cells die, apparently because formin Cdc12p rejects all of the fusion protein. Although fission yeast cells cannot survive on GFP–actin alone, they tolerate low levels of expression of GFP–actin in the presence of wild type levels of native actin (Wu and Pollard, 2005). These trace levels of GFP–actin can be used to make quantitative measurements of actin filaments in actin patches (Sirotkin et al., 2010) but not contractile rings.

Although probes such as fluorescent protein-tagged calponin homology domains (CHD) (Wachtler et al., 2003) and Lifeact (Riedl et al., 2008) can be used to label actin filaments indirectly in vivo, they have shortcomings. These probes bind actin filaments with Kds of about 2–50 μM (Gimona et al., 2002; Mateer et al., 2004; Riedl et al., 2008), thus they must be expressed at a relatively high concentration to detect actin filaments in cells, which could perturb the actin cytoskeleton. More importantly, none of these indirect fluorescent probes can be used for quantitative fluorescence microscopy to characterize the dynamics of actin filaments in live cells, which requires direct labeling of the protein being studied (Wu and Pollard, 2005). Here we inserted a tetracysteine peptide at 10 sites in fission yeast actin, and labeled these proteins with the FlAsH reagent in live cells (Adams et al., 2002; Griffin et al., 1998). The combined size of the peptide and dye is less than 2 kDa. Some tetracysteine tagged actins were incorporated into actin filaments nucleated by Arp2/3 complex in actin patches, but to our surprise formin Cdc12p excluded all of these labeled actin molecules from contractile rings. Here we explore the structural basis for this rejection of labeled actin by formins.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Mutagenesis and expression of mutant actins

Fission yeast strains with inserts in the actin gene were made by site directed mutagenesis. The strains used in this study are listed in Table 2. We subcloned the S. pombe act1+ cDNA into pFA6a-KanMX6 to make pFA6a-Act-KanMX6. Then we inserted the coding sequence for a peptide with a tetracysteine motif (FLNCCPGCCMEP) (Martin et al., 2005) into the actin coding sequence by site-directed mutagenesis (QuickChange II, Stratagene, CA) and used the plasmid to replace the ura4+ cassette in the diploid strain act1/Δact1::ura4+ by PCR-based integration (Bahler et al., 1998). Genomic DNA of the strains was extracted and sequenced to verify the desired insertions. Each resulting diploid strain act1/Δact1::act1*-KanMX6 was sporulated on SPA5s plates and dissected into at least 10 tetrads.

Table 2.

Yeast strain list.

| Yeast strains | Mating type | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| QC1 | h−/h+ | act1+/KanMX6-4cys-act1 ade6-M210/ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| QC28 | h−/h+ | act1+/kanMX6-3nmt1-4cys-(GS)3-act1 ade6-M210/ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| QC29 | h−/h+ | act1+/kanMX6-3nmt1-4cys-(GS)6-act1 ade6-M210/ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| QC5 | h−/h+ | act1+/KanMX6-act1-1-4cys ade6-M210/ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| QC27 | h−/h+ | act1+/KanMX6-act1-2-4cys ade6-M210/ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| QC14 | h−/h+ | act1+/KanMX6-act1-3-4cys ade6-M210/ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| QC17 | h−/h+ | act1+/KanMX6-act1-4-4cys ade6-M210/ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| QC19 | h−/h+ | act1+/KanMX6-act1-5-4cys ade6-M210/ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| QC18 | h−/h+ | act1+/KanMX6-act1-6-4cys ade6-M210/ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| QC20 | h−/h+ | act1+/KanMX6-act1-7-4cys ade6-M210/ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| QC21 | h−/h+ | act1+/KanMX6-act1-8-4cys ade6-M210/ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| QC13 | h−/h+ | act1+/KanMX6-act1-4cys ade6-M210/ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| JW1326 | h+ | 41nmt1-GFP-CHD(rng2)-leu1+ his3-D18 ura4-D18 leu1-32 ade6-M210 | Wu and Pollard (2005) and Wu et al. (2003) |

| FY527 | h− | leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 ade6-M216 | Lab stock |

| FY528 | h+ | leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 ade6-M216 | Lab stock |

| TP322 | h−/h+ | act1+/act1D::ura4+ ade6-M210/ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | Sirotkin et al. (2010) |

| TP359 | h−/h+ | act1+/kanMX6-3nmt1-mGFP-act1 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | Sirotkin et al. (2010) |

| QC306 | h− | 41nmt1-mGFP-act1-leu+ ura4-D18 his3-D1 ade6-M216 | This study |

2.2. Cell culture

Yeast cells were cultured according to standard protocols at 30 °C unless otherwise specified. Cells were pelleted in tabletop centrifuge at 3000 rpm for 1 min and washed with EMM5s medium before fluorescence microscopy. For expression of actin mutants driven by 3nmt1 promoter, the cells were grown overnight in YE5S medium containing thiamine to repress expression, before being washed and re-suspended in EMM5s medium without thiamine to induce the protein expression for variable times.

2.3. Labeling live cells with the FlAsH dye

Fresh overnight cultures of yeast cells were used for FlAsH labeling. A 0.5 mL culture of yeast in YE5S with an OD600 of 0.4–0.5 was inoculated with 2 μM FLAsH (molecular weight 664 Da) (Invitrogen, CA) and 5 μM BAL (2,3-dimercaptopropanol) and incubated at 30 °C for 2 h in the dark. Cells were washed with 3 mL EMM5s with 100 μM BAL for 10 min and 3 mL EMM5s for another 10 min.

2.4. Bodipy-phallacidin staining

To visualize actin filaments in fixed cells, we used a minor modification of a published method (Pelham and Chang, 2001). Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 5 min, washed with PEM buffer (0.1 M NaPIPES pH 6.8, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2), permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 in PEM for 2 min and washed with PEM buffer again before being stained with 860 μM Bodipy-phallacidin in PEM buffer (Invitrogen, CA).

2.5. Microscopy

Labeled cells were applied to a 25% gelatin pad made with EMM5s and sealed under a cover slip. Cells were imaged with a 100× Plan Apochromat objective lens (NA 1.40) on an Olympus IX-71 microscope equipped with a confocal spinning disk unit (Perkin Elmer Ultra-view RS) and a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Orca-ER, Hamamatsu). Images were processed using Image J (NIH) with free available plug-ins.

2.6. Structural analysis

We built molecular models using either Chimera (UCSF) or Py-MOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.2r3pre, Schrödinger, LLC).

3. Results

3.1. Mutagenesis strategy

To create sites in actin for labeling with the FlAsH reagent in live cells, we inserted the coding sequence for a dodecapeptide containing a tetracysteine motif (FLNCCPGCCMEP) at either the N- or C-terminus or at one of eight different internal sites in the fission yeast actin gene (Tables 1 and 2). All of the internal sites were in surface loops including three in the DNase binding loop (Fig. 1A). We avoided the nucleotide binding cleft and sites where actin is known to interact with other proteins such as profilin, capping protein and cofilin. We generally avoided sites that might interfere with interactions between subunits within the actin filament (Fig. 1C). Mutations act1-4 and act1-5 are exceptions, since they are located at the DNase-binding loop and have the potential to interfere with the assembly of actin filaments. We made these two mutants, because we thought that the flexible DNase-binding loop might be more accommodating to insertion of the tetracysteine hairpin loop than other parts of actin.

Table 1.

Location and functionality of tetracysteine labeling sites in fission yeast actin.

| Construct name | Insertion site | FlAsH labeling in fission yeast | Fluorescence in actin patches | Fluorescence in contractile rings | Fluorescence in cables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4cys-Act1 | N-terminus, M1^E2 | Yes | Yes | No | Weak |

| Act1-1-4cys | S232^S233 | Yes | Yes | No | Weak |

| Act1-2-4cys | A97^P98n | Yes | No | No | No |

| Act1-3-4cys | P322^S323 | Yes | No | No | No |

| Act1-4-4cys | P38^R39 | Yes | No | No | No |

| Act1-5-4cys | G46^M47^G48 | Yes | No | No | No |

| Act1-6-4cys | K50^D51 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Act1-7-4cys | P332^P333 | Yes | No | No | No |

| Act1-8-4cys | I75^V76 | Yes | No | No | No |

| Act1-4cys | C-terminus | Yes | No | No | No |

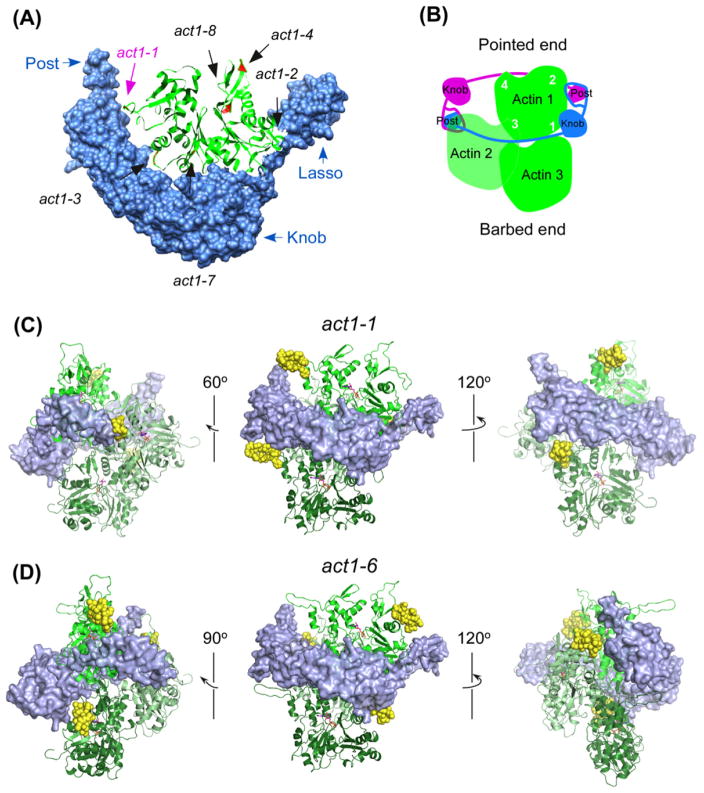

Fig. 1.

Tetracysteine tag insertion sites on the actin monomer and filament. (A) Ribbon diagram of fission yeast actin (green ribbon) modeled (SWISS-MODEL (Arnold et al., 2006; Kiefer et al., 2009)) on the structure of budding yeast actin (PDB: 1YAG) with the tetracysteine tag insertion sites highlighted in yellow and denoted by black arrows. The three mutants, which bound FlAsH dye and localized to the actin patches in vivo, are labeled in blue. (B) Ribbon diagram of the actin filament model based on PDB: 2ZWH (Oda et al., 2009). The bound nucleotides are shown in red stick representation. The numbers indicate the subdomains of one actin subunit in the filament, which is oriented similar to the actin in (A). (C) Surface representation of the actin filament model in the various mutants, in the same orientation as (B) except where specifically denoted. The insertion sites are highlighted in yellow and the nucleotide is shown in red.

3.2. Expression and labeling of tetracysteine–actin

Since the actin gene is essential, we worked with diploid strains having a native actin gene on one chromosome and the actin gene on the other chromosome deleted by insertion of the ura+ marker. We integrated the mutated actin coding sequences to replace the ura+ marker to create a diploid strain with one native actin gene and one mutant actin gene. Thus the native actin promoters drove the expression of both the native and mutant actins.

To test the functionality of the mutant actins, we sporulated the heterozygous diploid cells and found that none of the mutants supported the viability of the haploid strains. Thus, we carried out all of the following experiments with heterozygous diploid strains.

3.3. Fluorescence microscopy of labeled-actins in yeast cells

We labeled the tetracysteine actin by treating the live cells with 2 μM FlAsH and 5 μM BAL (2,3-dimercaptopropanol) for 2 h at 30 °C. BAL is critical to minimize unspecific binding of the FlAsH dye to proteins other than actin in the cells. Incubating cells with FlAsH dye for more than 2 h did not increase labeling.

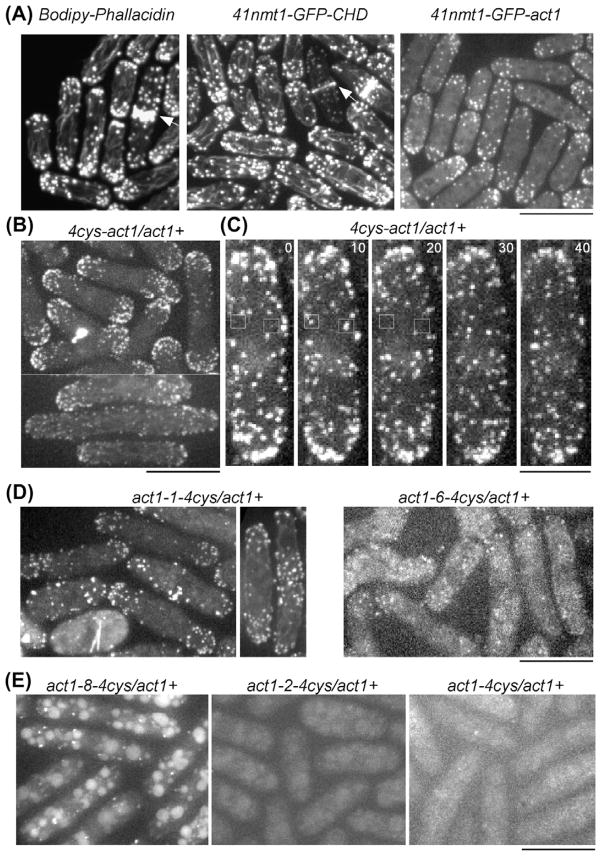

We used spinning disk confocal fluorescence microscopy to image live cells expressing mutant actins labeled with FlAsH. We compared the distribution and dynamics of the labeled actin in cells prepared by three conventional approaches (Fig. 2A). (i) Staining fixed cells with Bodipy-phallicidin brightly labeled actin patches (where Arp2/3 complex nucleates the actin filaments at sites of clathrin-mediated endocytosis), cytokinetic contractile rings (where formin Cdc12p nucleates the filaments (Chang et al., 1997)) and a few interphase cables (where formin For3p nucleates the actin filaments (Feierbach and Chang, 2001)). (ii) Live cells expressing GFP fused to the calponin homology domain of IQGAP Rng2p (GFP-CHD) had brightly fluorescent actin patches, contractile rings and interphase actin cables (Martin and Chang, 2006; Wachtler et al., 2003; Wu and Pollard, 2005). (iii) Cells expressing actin N-terminally tagged with GFP from an inducible 41xnmt1 promoter at a level about 6% of unlabeled actin had fluorescent actin patches but no fluorescence associated with the contractile ring or interphase actin cables (Wu and Pollard, 2005).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of methods to label actin filaments with fluorescent probes in fission yeast cells. Bars are 10 μM, except for that in (C) which is 5 μM. (A) Fluorescence micrographs of fission yeast cells with three different labeling strategies. Left, fixed cells stained with Bodipy-phallacidin. Middle, live cells expressing 41nmt1-GFP-CHD. Right, live cells expressing 41nmt1-GFP-act1 from the leu1 locus. Bodipy-phallacidin and GFP-CHD labeled all three cytoskeletal structures composed of actin filaments in the fission yeast cells, including actin patches, interphase actin cables and contractile rings (arrows). GFP-act1 localized only to the actin patches, not cables or contractile rings. (B–E) Fluorescence micrographs of live diploid cells expressing actin tagged with a tetracysteine peptide and labeled with FlAsH dye. (B and C) Cells expressing actin with an N-terminal tetracysteine tag and labeled with FlAsH. (B) FlAsH-4cys-act1 localized strongly to actin patches (upper) and very weakly to interphase actin cables (lower). (C) Time lapse fluorescence micrographs of cells showing the turnover of FlAsH-4cys-act1 in actin patches (squares). FlAsH-4cys-act1 appears and disappears in individual actin patches over about 10 s. Numbers are times in seconds. (D) Localization of two actin constructs with internal tetracysteine tags that localized to actin patches. Left, Act1-1-4cys labeled with FlAsH and localized to both actin patches and actin cables (right, weakly). Right, Act1-6-4cys labeled with FlAsH and localized to a small number of patches. (E) Actin constructs with tetracysteine tags that failed to localize to actin patches. Left, Act1-8-4cys, labeled with FlAsH but localized to aggregates and vacuoles. Middle, act1-2-4cys, labeled very weakly with FlAsH and concentrated in aggregates and vacuoles. Right, C-terminus tagged act1-4cys was distributed diffusely throughout the cells.

FlAsH dye labeled all 10 strains expressing actin mutants with tetracysteine tags, but not wild type cells. In three of these strains, fluorescence concentrated in actin patches and in two of these three labeled strains fluorescence also incorporated weakly into interphase actin cables, but none of the FlAsH-labeled actins incorporated into contractile rings (Table 1; Fig. 2B–E).

Actin with an N-terminal tetracysteine peptide (4cys-act1, Table 1) FlAsH-4cys-Act1 incorporated into actin patches at sites of endocytosis (Fig. 2B and C), where it assembled and then disappeared in about 10 s, similar to observations with GFP–actin and GFP-fusion proteins that bind actin filaments such as the Rng2p calponin homology domain (Wachtler et al., 2003; Wu and Pollard, 2005) or fimbrin (Sirotkin et al., 2010). FlAsH-4cys-Act1 also incorporated into the formin For3p dependent interphase actin cables (Fig. 2B), although the fluorescence was very weak compared to that in cells stained with Bodipy-phallicidin or expressing GFP-CHD (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, no FlAsH-4cys-actin fluorescence above the diffuse cytoplasmic fluorescence was detected in the contractile rings, which depend on formin Cdc12p.

In an effort to detect low levels of fluorescent actin in contractile rings, we over-expressed actins with an N-terminal tetracysteine tag by replacing the endogenous actin promoter with an inducible strong 3xnmt1 promoter. We also inserted (GS)3 or (GS)6 linkers between N-terminal tetracysteine tag and actin. These over-expressed, labeled actins incorporated into actin patches and aberrant actin filament bundles, but not contractile rings (data not shown). We also attached a shorter version of tetracysteine tag (CCPGCC, molecular weight = 0.6 kDa) to the N-terminus of actin, but it also failed to incorporate into contractile rings (data now shown).

Actin with a C-terminal tetracysteine tag could be labeled with the FlAsH dye. However, in contrast to the N-terminally tagged constructs, none of the labeled protein incorporated into any of structures containing actin filaments (Fig. 2E).

Three of eight actin mutants with internal tetracysteine insertions bound FlAsH in cells. FlAsH-Act1-1-4cys with a tetracysteine tag inserted in subdomain 4 incorporated into both actin patches and actin cables (Fig. 2D). FlAsH-Act1-6-4cys with an insertion in the DNase binding loop could be labeled but incorporated only weakly in actin patches (Fig. 2D). FlAsH-Act1-8-4cys did not concentrate in any structures known to contain actin filaments, but rather was mostly in aggregates and vacuoles (Fig. 2E). The other five insertion mutants had only diffuse fluorescence throughout cells after FlAsH labeling.

4. Discussion

We added tetracysteine tags at eight internal sites in fission yeast actin in addition to the N- and C-termini. The FlASH dye labeled most of these mutant proteins in live cells. Six of the actins with inserted tags and actin with the C-terminal tag were not incorporated into any actin structure. Models of the actin filament (Oda et al., 2009) (Fig. 1C) showed that inserts at these six sites are likely to interfere with actin polymerization, so they were excluded from all the filaments. The tetracysteine tags in act1-4 and act1-5 are inserted into the DNase binding loop that forms key interactions between vertically adjacent actin subunits in the filament. Similarly, the tetracysteine tag in act1-3 is located at the interface between subdomain 4 of an actin subunit and subdomain 3 of the subunit above it. It is highly probable that the 12-residue hairpin formed by the tetracysteine tag at these sites disrupts these interactions through steric clashes and thus prevents the incorporation of the actin mutants into filaments. Inserts at the act1-8 and act1-4cys sites make steric clashes with the actin subunit of the neighboring actin strand. No steric clashes are evident from the position of the insertion sites of act1-2 and act1-7. However, the proximity of the tags in act1-2 to the interface between subdomains 1 and 2 and in act1-7 to the nucleotide-binding site may cause conformational changes or destabilize the protein such that these mutants cannot incorporate into filaments.

Three of the FlAsH-labeled proteins incorporated into actin filaments in actin patches mediated by Arp2/3 complex, but none incorporated into the actin filaments of contractile rings, which depend on formin Cdc12p. Fission yeast formin Cdc12p accepts actin subunits tagged with Oregon green on cysteine 374 in assays with purified proteins (Kovar et al., 2003), but in cells, Cdc12p rejects actin subunits with a tetracysteine–FlAsH tag of around 2 kDa on three different sites or a fluorescent protein tag (molecular weight 27 kDa) on either the N- or C-termini. This striking result illustrates the stringent structural requirements for this formin to promote the elongation of actin filament barbed ends as it moves processively along the end of a growing filament.

To understand why formin Cdc12p does not incorporate FlAsH-labeled actins into contractile rings, we examined the crystal structure of the FH2 domain of budding yeast formin Bni1p cocrystallized with actin (Otomo et al., 2005). In these crystals actin forms a polymer with twofold symmetry rather than the ~167° rotation of the short-pitch helix of an actin filament (Fig. 3). The FH2 domains are linked head-to-tail in a helix around the actin polymer rather than in head-to-tail dimers. Nevertheless, this structure provides the most detail about the interactions of FH2 domains with actin. Two regions of the FH2 dimer interact directly with actins in the structure. The knob region mainly contacts barbed end of the actin dimer, at the cleft between subdomains 1 and 3 of the first actin. The lasso/post region contacts the subdomain 1 of the other actin. Although none of the tetracysteine peptide insertion sites in actin are located within the Bni1-FH2-actin interface in the cocrystal structure (Fig. 3A), some of them are in close proximity. For example, the insertion site in Act1-1-4cys, Ser232/Ser233, is in the same loop with Asn225, which interacts with the lasso/post region of the FH2 dimer (Goode and Eck, 2007).

Fig. 3.

Models of tagged actins associated with an FH2 domain. (A) Space-filling model of the structure of one FH2 domain of budding yeast Bni1 cocrystallized with actin (PDB: 1Y64) (Otomo et al., 2005) showing the locations of sites tagged with GFP or tetracysteine. The surface rendering of the FH2 domain is blue and the ribbon diagram of actin is green. Red: locations of tetracysteine insertions. Blue: three subdomains of the FH2. A magenta arrow points to the insertion in act1-1 that could be labeled with FlAsH and incorporated into actin patches but not contractile rings. Black arrows point to insertions that could be labeled with FlAsH but were not incorporated into any actin cytoskeletal structures. Part of the DNase loop, N-terminus and C-terminus of the actin are missing in the structure. Therefore, act1-5, act1-6, 4cys-act1 and act1-4cys are not shown in this model. (B–D) show models of FH2 domains bound to actin filaments after adding a new subunit to the barbed end and before stepping onto this new subunit. (B) Cartoon of the barbed end of an actin filament (green), showing three subunits, associated with an FH2 dimer (one subunit in blue and the other in purple) as seen in (C) and (D). The actin subunit 1 (Actin 1) has the same orientation as actin in (A) with numbers (white) indicating its four subdomains. (C and D) Models of the FH2 domain bound to tetracysteine-tagged F-actin show how the tags may interfere with actin filament elongation. A single FH2 subunit (blue surface, 1Y64, (Otomo et al., 2005)) is bound to actin protomer 1 (as in B) of labeled filamentous actin (green ribbon, with insertions in yellow space filled representation PDB: 2ZWH (Oda et al., 2009)). (C) Act1-1-4cys tagged actin bound to FH2 (front view, center panel). The hairpin loop formed by the tetracysteine tag displays a clash with the knob region of FH2 (side view, left panel). Additionally, the insertion is also likely to impede the stepping of FH2 onto a subunit added to the barbed end (side view, right panel). (D) The Act1-6-4cys tagged actin bound to FH2 (front view, center panel). There are no obvious clashes between the tetracysteine insertion in the displayed conformation and bound FH2. However, the loop could prevent the movement of FH2 necessary for actin filament elongation (side view, left panel). The images were prepared with Pymol.

We focused particularly on the two actin mutants, act1-1 and act1-6, that were incorporated into actin patches but not contractile rings through homology modeling. We modeled the tetracysteine peptide into the actin structure, assuming that it forms a hairpin loop (Adams et al., 2002) (Fig. 3C and D). The insertion in act1-1 results in a steric clashes with the FH2 domain, but the one in act1-6 does not.

The actin N-terminus is adjacent to residues that interact with both the knob and lasso/post region of the FH2 dimer. We did not model 4cys-act1, because we could not model the structure of its N-terminus inserted tetracysteine tag without constraints imposed by the flanking structures. However, a hairpin formed by the tetracysteine tag fused to the N-terminus, as present in 4cys-act1, would surely clash with these parts of the FH2 domain.

Insertions in all three of these actin mutants have the potential to interfere with the movement of the FH2 dimer as it steps onto the next actin subunit added to the barbed end during elongation. For example, the location of the tag on act1-6 mutant (Fig. 3D) suggests that small movements of the FH2 may result in steric clashes. This may explain the exclusion of these three actin mutants from the contractile ring actin filaments mediated by Cdc12p.

Alternatively or in addition, Cdc12p may interact more intimately with actin than Bni1p. Of the formins that have been studied carefully, Cdc12p stands out in two regards that suggest tighter interactions with the barbed end of actin filaments than other formins (Goode and Eck, 2007; Paul and Pollard, 2009b). All formins associate processively with growing actin filament barbed ends and all slow barbed end growth to some extent. Cdc12p is the extreme example, slowing elongation by >95%, whereas Bni1p slows elongation by only 50%, and mDia1 slows elongation by less than 10% (Paul and Pollard, 2009a). All known FH2 domains dissociate slowly from actin filament barbed ends, and the FH2 dimer of Cdc12p is the most processive (Paul and Pollard, 2009a), so its interactions with actin may be very strong. A possible explanation for these strong interactions of the Cdc12p FH2 domain with actin is the fact that the flexible linker connecting the knob and post/lasso region in the FH2 domain of Cdc12 is shorter (14 residues) than the 17 residue linker of Bni1 or the 23 residue linker of mDia1. However, experiments with chimeric proteins consisting of Bni1p-FH2 domains with linkers from Cdc12p or mDia1 showed that length of the linker alone does not account for the differences in slow elongation and dissociating from growing barbed ends (Paul and Pollard, 2009a). The other features of the Cdc12p FH2 domain may be responsible for these strong interactions of Cdc12p with actin filaments, which allow less tolerance for tagged actin during polymerization.

A crystal structure of Cdc12p FH2 dimer with actin would allow for comparison with Bni1p and give further insights into how formins filter out tagged actin mutants. The only other available structure of FH2 dimer is human Daam1. These two FH2 structures are generally similar, but there are significant differences between in their knob regions (Lu et al., 2007).

Tagging Drosophila actin on the N-terminus vs. C-terminus with small peptides gave results similar to ours ((Brault et al., 1999) of which Ueli Abei is a co-author). Drosophila actin with either a 6xHis or 11-mer epitope tag on the N-terminus partially rescued the null phenotype in the indirect flight muscle (IFM), while actin with C-terminal peptide tags failed completely. Brault et al. hypothesized that N-terminal tags interfere with interactions between myosin II and the actin filaments, thus resulting in a partial defect in the function of the tagged actin. Our data instead showed that the N-terminal FlAsH-4cys tag on actin more likely interferes with formin Cdc12p binding to actin filaments, similar to the tetracysteine tags at either the act1-1 and act1-6 sites.

To our knowledge, no formin has incorporated an actin tagged on the N-terminus with GFP into the actin filaments of a contractile ring. Instead, many reports have noted the failure of N-terminal tagged GFP–actin to incorporate into contractile ring in a wide range of species including fission yeast (Pelham and Chang, 2002; Wu and Pollard, 2005), Dictyostelium (Gerisch and Weber, 2000) and Caenorhabditis elegans (Carvalho et al., 2009). Nor are we aware of a report of GFP–actin incorporating to contractile rings in fruit fly cells. Expression of GFP–actin even caused cytokinesis defects in Dictyostelium (Aizawa et al., 1997). The only exceptions are a few studies that showed GFP–actin in contractile rings/cleavage furrows in animal tissue culture cells, which may have resulted from cortical flow of actin filaments nucleated by Arp2/3 complex into the cleavage furrow during cytokinesis (Murthy and Wads-worth, 2005; Zhou and Wang, 2008).

5. Conclusions

Fission yeast cells incorporated three different FlAsH-actin constructs to filaments nucleated by Arp2/3 complex at sites of endocytosis but not into the contractile ring. Therefore, Cdc12p, the fission yeast formin required for the assembly of contractile rings, has very stringent structural requirements for incorporating subunits at actin filament barbed ends as it moves processively along the end of a growing filament.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH research Grants GM026132 and GM-026338. The authors thank Vladimir Sirotkin and Naomi Courtemanche for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

Dedication: On the occasion of Ueli Aebi’s retirement, I am happy to share some of our recent work on Ueli’s second most favorite protein, actin. Ueli and I enjoyed working together on actin in the early 1980s at the Johns Hopkins Medical School. With Gerhard Isenberg we discovered capping protein (Isenberg et al., 1980) and with Ross Smith determined an excellent low resolution structure of the actin molecule based on three-dimensional reconstructions from electron micrographs of two-dimensional crystals of actin (Aebi et al., 1980). Rather than attempting in this paper a comprehensive review of our recent work on the role of actin in cytokinesis and cellular motility, we will describe one new result regarding the structural requirements for formins to elongated actin filaments. Thomas D. Pollard, New Haven, CT, USA, 2011.

References

- Adams SR, Campbell RE, Gross LA, Martin BR, Walkup GK, et al. New biarsenical ligands and tetracysteine motifs for protein labeling in vitro and in vivo: synthesis and biological applications. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:6063–6076. doi: 10.1021/ja017687n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aebi U, Smith PR, Isenberg G, Pollard TD. Structure of crystalline actin sheets. Nature. 1980;288:296–298. doi: 10.1038/288296a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aizawa H, Sameshima M, Yahara I. A green fluorescent protein-actin fusion protein dominantly inhibits cytokinesis, cell spreading, and locomotion in Dictyostelium. Cell Struct Funct. 1997;22:335–345. doi: 10.1247/csf.22.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahler J, Steever AB, Wheatley S, Wang Y, Pringle JR, et al. Role of polo kinase and Mid1p in determining the site of cell division in fission yeast. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1603–1616. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brault V, Sauder U, Reedy MC, Aebi U, Schoenenberger CA. Differential epitope tagging of actin in transformed Drosophila produces distinct effects on myofibril assembly and function of the indirect flight muscle. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:135–149. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.1.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho A, Desai A, Oegema K. Structural memory in the contractile ring makes the duration of cytokinesis independent of cell size. Cell. 2009;137:926–937. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang F, Drubin D, Nurse P. Cdc12p, a protein required for cytokinesis in fission yeast, is a component of the cell division ring and interacts with profilin. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:169–182. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feierbach B, Chang F. Roles of the fission yeast formin for3p in cell polarity, actin cable formation and symmetric cell division. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1656–1665. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00525-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerisch G, Weber I. Cytokinesis without myosin II. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:126–132. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimona M, Djinovic-Carugo K, Kranewitter WJ, Winder SJ. Functional plasticity of CH domains. FEBS Lett. 2002;513:98–106. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode BL, Eck MJ. Mechanism and function of formins in the control of actin assembly. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:593–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin BA, Adams SR, Tsien RY. Specific covalent labeling of recombinant protein molecules inside live cells. Science. 1998;281:269–272. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg G, Aebi U, Pollard TD. An actin-binding protein from Acanthamoeba regulates actin filament polymerization and interactions. Nature. 1980;288:455–459. doi: 10.1038/288455a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer F, Arnold K, Kunzli M, Bordoli L, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL Repository and associated resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D387–D392. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovar DR, Pollard TD. Insertional assembly of actin filament barbed ends in association with formins produces piconewton forces. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14725–14730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405902101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovar DR, Sirotkin V, Lord M. Three’s company: the fission yeast actin cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:177–187. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovar DR, Kuhn JR, Tichy AL, Pollard TD. The fission yeast cytokinesis formin Cdc12p is a barbed end actin filament capping protein gated by profilin. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:875–887. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovar DR, Harris ES, Mahaffy R, Higgs HN, Pollard TD. Control of the assembly of ATP- and ADP-actin by formins and profilin. Cell. 2006;124:423–435. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Meng W, Poy F, Maiti S, Goode BL, et al. Structure of the FH2 domain of Daam1: implications for formin regulation of actin assembly. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:1258–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin BR, Giepmans BN, Adams SR, Tsien RY. Mammalian cell-based optimization of the biarsenical-binding tetracysteine motif for improved fluorescence and affinity. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1308–1314. doi: 10.1038/nbt1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SG, Chang F. Dynamics of the formin for3p in actin cable assembly. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1161–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateer SC, Morris LE, Cromer DA, Bensenor LB, Bloom GS. Actin filament binding by a monomeric IQGAP1 fragment with a single calponin homology domain. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2004;58:231–241. doi: 10.1002/cm.20013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell JL, Morphew M, Gould KL. A mutant of Arp2p causes partial disassembly of the Arp2/3 complex and loss of cortical actin function in fission yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:4201–4215. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.12.4201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy K, Wadsworth P. Myosin-II-dependent localization and dynamics of F-actin during cytokinesis. Curr Biol. 2005;15:724–731. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda T, Iwasa M, Aihara T, Maeda Y, Narita A. The nature of the globular-to fibrous-actin transition. Nature. 2009;457:441–445. doi: 10.1038/nature07685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otomo T, Tomchick DR, Otomo C, Panchal SC, Machius M, et al. Structural basis of actin filament nucleation and processive capping by a formin homology 2 domain. Nature. 2005;433:488–494. doi: 10.1038/nature03251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul AS, Pollard TD. The role of the FH1 domain and profilin in formin-mediated actin-filament elongation and nucleation. Curr Biol. 2008;18:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul AS, Pollard TD. Energetic requirements for processive elongation of actin filaments by FH1FH2-formins. J Biol Chem. 2009a;284:12533–12540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808587200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul AS, Pollard TD. Review of the mechanism of processive actin filament elongation by formins. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2009b;66:606–617. doi: 10.1002/cm.20379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham RJ, Chang F. Actin dynamics in the contractile ring during cytokinesis in fission yeast. Nature. 2002;419:82–86. doi: 10.1038/nature00999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham RJ, Jr, Chang F. Role of actin polymerization and actin cables in actin-patch movement in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:235–244. doi: 10.1038/35060020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard TD, Wu JQ. Understanding cytokinesis: lessons from fission yeast. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:149–155. doi: 10.1038/nrm2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl J, Crevenna AH, Kessenbrock K, Yu JH, Neukirchen D, et al. Lifeact: a versatile marker to visualize F-actin. Nat Methods. 2008;5:605–607. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirotkin V, Berro J, Macmillan K, Zhao L, Pollard TD. Quantitative analysis of the mechanism of endocytic actin patch assembly and disassembly in fission yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2894–2904. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-02-0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vavylonis D, Wu JQ, Hao S, O’Shaughnessy B, Pollard TD. Assembly mechanism of the contractile ring for cytokinesis by fission yeast. Science. 2008;319:97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1151086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachtler V, Rajagopalan S, Balasubramanian MK. Sterol-rich plasma membrane domains in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:867–874. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JQ, Pollard TD. Counting cytokinesis proteins globally and locally in fission yeast. Science. 2005;310:310–314. doi: 10.1126/science.1113230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JQ, Kuhn JR, Kovar DR, Pollard TD. Spatial and temporal pathway for assembly and constriction of the contractile ring in fission yeast cytokinesis. Dev Cell. 2003;5:723–734. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00324-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Moseley JB, Sagot I, Poy F, Pellman D, et al. Crystal structures of a Formin Homology-2 domain reveal a tethered dimer architecture. Cell. 2004;116:711–723. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Wang YL. Distinct pathways for the early recruitment of myosin II and actin to the cytokinetic furrow. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:318–326. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]