Abstract

A systematic electronic PubMed, Medline and Web of Science database search was conducted regarding the prevalence, correlates, and effects of personal stigma (i.e., perceived and experienced stigmatization and self-stigma) in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Of 54 studies (n=5,871), published from 1994 to 2011, 23 (42.6%) reported on prevalence rates, and 44 (81.5%) reported on correlates and/or consequences of perceived or experienced stigmatization or self-stigma. Only two specific personal stigma intervention studies were found. On average, 64.5% (range: 45.0–80.0%) of patients perceived stigma, 55.9% (range: 22.5–96.0%) actually experienced stigma, and 49.2% (range: 27.9–77.0%) reported alienation (shame) as the most common aspect of self-stigma. While socio-demographic variables were only marginally associated with stigma, psychosocial variables, especially lower quality of life, showed overall significant correlations, and illness-related factors showed heterogeneous associations, except for social anxiety that was unequivocally associated with personal stigma. The prevalence and impact of personal stigma on individual outcomes among schizophrenia spectrum disorder patients are well characterized, yet measures and methods differ significantly. By contrast, research regarding the evolution of personal stigma through the illness course and, particularly, specific intervention studies, which should be conducted utilizing standardized methods and outcomes, are sorely lacking.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, psychosis, stigma, self-stigma, personal stigma, perceived stigma, correlates

Psychiatric stigma research has been, up until recently, primarily focused on public concepts of mental illness and the negative reactions toward mentally ill persons displayed by individuals or societal groups 1–3. Several disease and patient characteristics have been identified as factors influencing stigmatization 4,5, and anti-stigma initiatives have been established to decrease stigmatizing attitudes and discriminating actions in individuals and society as a whole 6,7. In the past decade, however, a better understanding of the stigma process has shifted the attention from public stigma to the subjective experience of stigmatized people. Research has identified inter-individual variables that might increase or decrease the impact of stigma on the individual 8, as well as intra-individual variables that modify the impact of stigma on health-related outcomes. This new focus of interest was accompanied by a growing body of research regarding therapeutic interventions that address those intra- and inter-individual characteristics in mentally ill people aiming to reduce the prevalence and negative effects of stigma 9–12.

In recent years, the proposed inclusion of the attenuated psychosis syndrome in the DSM-5 has raised concerns about the potential stigmatization of patients being labelled “at-risk” 13–16, particularly considering the high number of false positives (only approximately 30% of patients showing putative initial prodromal symptoms eventually develop psychosis within the following 2.5 years) 17–19. This also raises the question of whether different stages of schizophrenia spectrum disorders – i.e., the clinical high risk syndrome, first episode and chronic illness – may be differently impacted by stigma and self-stigma.

In order to evaluate stigma research, a precise definition of “stigma” is relevant. In the majority of studies, Goffman's classical proposal that stigma is an “attribute that is deeply discrediting” and that reduces the person who bears it “from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one” 20 serves as the basic definition that authors expand on. Link and Phelan 21, however, criticize the striking variability of stigma definitions used by members of different disciplines and redefine stigma as the co-occurrence of “labelling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination”.

A further important terminological distinction is that between public stigma (i.e., “the general population endorses prejudice and manifests discrimination toward people with mental illness” 22) and personal stigma (consisting of perceived stigma, experienced stigma and self-stigma). The perception or anticipation of stigma refers to people's beliefs about attitudes of the general population towards their condition and towards themselves as members of a potentially stigmatized group 23. Experienced stigma refers to discrimination or restrictions actually met by the affected persons. Lastly, the internalization and adoption of stereotypic or stigmatizing views, i.e., of public stigma, by the stigmatized individual is referred to as self-stigma or internalized stigma 12. Self-stigma has also been defined as a type of identity transformation that might lead to the loss of previously held (positive) beliefs about the self, which in turn yields negative consequences for the person such as diminished self-esteem and self-efficacy 24. In this systematic review, we focused exclusively on publications containing data on any of the above-mentioned three definitions of personal stigma.

Despite the importance of personal stigma, to our knowledge, no systematic review has been published on this topic to date. Therefore, we sought to systematically review the prevalence, correlates and consequences of personal stigma in people suffering from schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Furthermore, we aimed to evaluate whether quantitative or qualitative differences in personal stigma exist depending on the illness phase, hypothesizing that personal stigma would increase with increasing illness duration and experience. We further aimed to assess whether interventions have been tested specifically targeting personal stigma in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Finally, we sought to evaluate the strengths and deficiencies of the current evidence base in order to identify gaps that need to be addressed by further research.

METHODS

A systematic literature review was conducted to identify studies reporting on the prevalence, correlates and effects of personal stigma in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. We conducted an electronic PubMed, Medline, and Web of Science search for published, peer reviewed articles using the following keywords: “schizophrenia”/“psychosis”/“prodrome”/“ultra high risk”/“clinical high risk” AND “stigma”/“self-stigma”, without time or language restrictions. Additionally, the reference lists of identified articles and of two reviews on stigma scales 25,26 and two narrative reviews on personal stigma 16,27 were screened to identify additional articles. To be included in this review, articles had to meet all of the following inclusion criteria: a) reporting on personal, not public stigma; b) a majority of the sample (≥70%) diagnosed with schizophrenia or a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, or results for this diagnostic subgroup being reported separately; c) quantitative or semi-quantitative data available on prevalence, correlates or impact of personal stigma or regarding an intervention addressing personal stigma.

With regard to prevalence data, means and percentages were weighted for the number of cases included in a particular study, whenever possible. To calculate weighted percentages of personal stigma dimensions, only proportions of rating scale scores were used. If a scale measured more than two levels (“yes” vs. “no”), reported proportions of scores greater than the scale's midpoint were used. Mean scores of scales were not summarized and are not reported here, as there were too few studies using the same scales or subscales.

To categorize results regarding prevalence of anticipated/perceived and experienced stigma, we used the conceptual framework implemented in the Inventory of Stigma Experiences of Psychiatric Patients 28, containing the following four domains: a) interpersonal interaction, b) public image of mentally ill people, c) access to social roles, and d) structural discrimination. In order to indicate which proportion of patients had anticipated/perceived or experienced stigma at all (in at least one of the categories), one overall domain was created using the domain with the highest reported prevalence of stigma per study and sample.

To categorize results regarding self-stigma, we used the subscales alienation, stereotype endorsement (stereotype agreement), self-esteem decrement and stigma resistance of the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (ISMI, 25) and the Self-stigma of Mental Illness Scale (SSMIS, 22). The subscale stigma resistance indicates the individual's ability to defy internalization of stigma and is negatively correlated with all other domains of self-stigma. Since the domains of self-stigma are interrelated and interact hierarchically, no overall category was created.

RESULTS

The search for “schizophrenia” AND “stigma” yielded 377 hits, “psychosis” AND “stigma” 136, “prodrome” AND “stigma” 4, “ultra high risk” AND “stigma” 0, “clinical high risk” AND “stigma” 2, “schizophrenia” AND “self-stigma” 16, and “psychosis” AND “self-stigma” 6 hits, adding up to an overall number of 541 hits. After deleting duplicates, 457 articles were retained, all being in English.

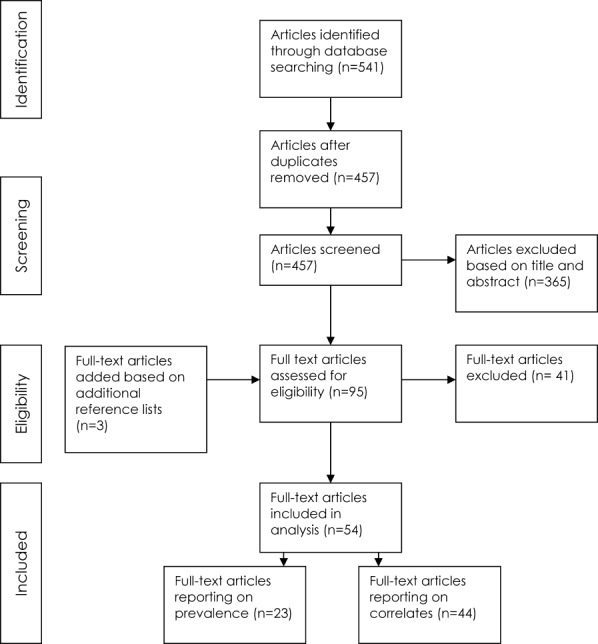

Based on title and abstract, 365 articles were excluded due to lack of relevance. Most of these excluded articles focused on public attitudes and stereotypes toward people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (public stigma), or the burden on family members and relatives of psychiatric patients, or reported on the need for and the benefit of public anti-stigma initiatives concerning mental illness or schizophrenia. Some discussed the need for “relabeling” schizophrenia in order to decrease stigma 29. Three articles were added after checking additional reference lists. After thoroughly examining 95 studies, 54 articles, published between 1994 and 2011, met our inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Review process

Prevalence of personal stigma

Twenty-three (42.6%) of the 54 included publications reported on the prevalence of anticipated stigma (n=12), experienced stigma (n=17), or self-stigma (n=6). Among these, 15 studies reported primarily on correlates of personal stigma, while assessing prevalence was only secondary. Sample sizes ranged from 31 to 1,229 participants (total n=5,871, mean: n=267), mean age ranged from 24.5 (SD=6.3) to 54.3 (SD=16.6) years, and the percentage of male participants ranged between 38 and 71%. Participants were mostly outpatients and without specific focus on or restriction to individual illness stages or severity of disease. While surveys and interviews were implemented in as many as 40 countries, the majority of subjects (71.7%) were assessed in Europe and the USA.

Rates of anticipated/perceived stigma ranged from 33.7% in insurance-related structural discrimination 28 to 80% in interpersonal interactions 30, with a weighted percentage of 64.5% of all patients anticipating/perceiving stigma regarding at least one of the given categories (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of anticipated/perceived stigmatization

| Study | N | Prevalence (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 69.0 |

| Berge & Ranney 30 | 31 | 80.0 | |

| Cechnicki et al 31 | 202 | 58.0 | |

| Dickerson et al 32 | 74 | 70.0 | |

| Ertugrul & Ulug 33 | 60 | 45.0 | |

| Karidi et al 34 | 150 | 66.7 | |

| Kleim et al 35 | 127 | 64.0 | |

| Lai et al 36 | 72 | 51.0 | |

| Lee et al 37 | 320 | 69.7 | |

| McCann et al 38 | 81 | 74.0 | |

| Tarrier et al 39 | 35 | 53.1 | |

| Thornicroft et al 40 | 732 | 64.0 | |

| 1985 | 64.5 | ||

| Interpersonal interaction | |||

| Rejection | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 64.4 |

| Cechnicki et al 31 | 202 | 58.0 | |

| Kleim et al 35 | 127 | 64.0 | |

| Lai et al 36 | 72 | 51.0 | |

| Avoidance | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 66.3 |

| Karidi et al 34 | 150 | 67.7 | |

| Others | Berge & Ranney 30 | 31 | 80.0 |

| McCann et al 38 | 81 | 74.0 | |

| 865 | 63.9 | ||

| Public image of mentally ill people | |||

| Media coverage | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 66.0 |

| Representation in feature films | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 66.0 |

| General | Cechnicki et al 31 | 202 | 41.0 |

| Dickerson et al 32 | 74 | 70.0 | |

| 478 | 56.3 | ||

| Access to social roles | |||

| Occupation | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 69.0 |

| Berge & Ranney 30 | 31 | 51.6 | |

| Cechnicki et al 31 | 202 | 55.0 | |

| McCann et al 38 | 81 | 51.4 | |

| Thornicroft et al 40 | 732 | 64.0 | |

| Partnership | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 44.6 |

| Berge & Ranney 30 | 31 | 74.2 | |

| Cechnicki et al 31 | 202 | 40.0 | |

| Thornicroft et al 40 | 732 | 55.0 | |

| Friendship | Berge & Ranney 30 | 31 | 53.3 |

| 2244 | 56.8 | ||

| Structural discrimination | |||

| Insurance | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 33.7 |

| Rehabilitation | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 42.6 |

| General | Cechnicki et al 31 | 202 | 49.0 |

| 404 | 43.6 |

For total percentage, mean values were weighted for the number of cases included in a particular study

Concerning experienced stigma, rates ranged from 6% regarding structural stigma 31 to 87% of patients having experienced rejection in interpersonal relations 31, with a weighted proportion of 55.9% of all patients having encountered stigma in at least one of the reported contexts (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of experienced stigmatization

| Study | N | Prevalence (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 60.0 |

| Baldwin & Marcus 41 | 86 | 29.0 | |

| Botha et al 42 | 100 | 65.0 | |

| Brohan et al 43 | 904 | 69.4 | |

| Cechnicki et al 31 | 202 | 87.0 | |

| Chee et al 44 | 306 | 39.0 | |

| Dickerson et al 32 | 74 | 55.0 | |

| Ertugrul & Ulug 33 | 60 | 45.0 | |

| Jenkins & Carpenter-Song 45 | 90 | 96.0 | |

| Karidi et al 34 | 150 | 32.5 | |

| Lai et al 36 | 72 | 73.0 | |

| Lee et al 37 | 320 | 68.0 | |

| Loganathan & Murthy 46 | 200 | 22.5 | |

| Sibitz et al 47 | 157 | 37.6 | |

| Switaj 48 | 153 | 69.0 | |

| Thornicroft et al 40 | 732 | 47.0 | |

| Werner et al 49 | 86 | 27.4 | |

| 3793 | 55.9 | ||

| Interpersonal interaction | |||

| Rejection | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 60.0 |

| Cechnicki et al 31 | 202 | 87.0 | |

| Jenkins & Carpenter-Song 45 | 90 | 18.6 | |

| Lee et al 50 | 320 | 48.0 | |

| Avoidance | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 51.5 |

| Karidi et al 34 | 150 | 32.5 | |

| Switaj 48 | 153 | 41.2 | |

| Offense | Botha et al 42 | 100 | 58.0 |

| Dickerson et al 32 | 74 | 55.0 | |

| Loganathan & Murthy 46 | 200 | 22.5 | |

| Switaj 48 | 153 | 69.0 | |

| Others | Botha et al 42 | 100 | 39.0 |

| Cechnicki et al 31 | 202 | 50.0 | |

| Jenkins & Carpenter-Song 45 | 90 | 47.7 | |

| Karidi et al 34 | 150 | 10.0 | |

| Lee et al 37 | 320 | 68.0 | |

| Switaj 48 | 153 | 59.0 | |

| 2659 | 49.9 | ||

| Public image of mentally ill people | |||

| Media coverage | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 38.0 |

| Dickerson et al 32 | 74 | 43.0 | |

| Lai et al 36 | 72 | 46.0 | |

| Switaj 48 | 153 | 45.0 | |

| Representation in feature films | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 40.6 |

| Others | Cechnicki et al 31 | 202 | 38.0 |

| Jenkins & Carpenter-Song 45 | 90 | 24.4 | |

| Switaj 48 | 153 | 63.0 | |

| 946 | 42.8 | ||

| Access to social roles | |||

| Occupation | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 19.0 |

| Baldwin & Marcus 41 | 86 | 29.0 | |

| Cechnicki et al 31 | 202 | 31.0 | |

| Jenkins & Carpenter-Song 45 | 90 | 36.0 | |

| Lai et al 36 | 72 | 73.0 | |

| Lee et al 37 | 320 | 46.8 | |

| Thornicroft et al 40 | 732 | 29.0 | |

| Partnership | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 21.6 |

| Cechnicki et al 31 | 202 | 42.0 | |

| Jenkins & Carpenter-Song 45 | 90 | 32.6 | |

| Thornicroft et al 40 | 732 | 27.0 | |

| Others | Thornicroft et al 40 | 732 | 47.0 |

| Thornicroft et al 40 | 732 | 43.0 | |

| 4192 | 36.9 | ||

| Structural discrimination | |||

| Insurance | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 15.8 |

| Lai et al 36 | 72 | 40.0 | |

| Rehabilitation | Angermeyer et al 28 | 101 | 13.9 |

| Lee et al 50 | 320 | 44.0 | |

| Others | Cechnicki et al 31 | 202 | 6.0 |

| 796 | 26.6 |

For total percentage, mean values were weighted for the number of cases included in a particular study

A weighted percentage of 52.6% of patients reported stigma resistance, 49.2% alienation (shame), 35.2% self-esteem decrement and 26.8% stereotype endorsement/agreement (Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence of self-stigma/internalized stigma

| Study | N | Prevalence (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General self-stigma | Brohan et al 43 | 904 | 41.7 |

| Alienation shame | Botha et al 42 | 100 | 77.0 |

| Lai et al 36 | 72 | 47.0 | |

| Sibitz et al 47 | 157 | 43.9 | |

| Werner et al 49 | 86 | 27.9 | |

| 415 | 49.2 | ||

| Stereotype endorsement/agreement | Botha et al 42 | 100 | 42.0 |

| Sibitz et al 47 | 157 | 15.2 | |

| Werner et al 49 | 86 | 30.0 | |

| 343 | 26.8 | ||

| Self-decrement, self-esteem decrement | Jenkins & Carpenter-Song 51 | 90 | 20.9 |

| Lai et al 36 | 72 | 53.0 | |

| 162 | 35.2 | ||

| Stigma resistance | Botha et al 42 | 100 | 84.0 |

| Brohan et al 43 | 904 | 49.2 | |

| Sibitz et al 47 | 157 | 63.3 | |

| Werner et al 49 | 86 | 32.5 | |

| 1247 | 52.6 |

For total percentage, mean values were weighted for the number of cases included in a particular study

Correlates and effects of personal stigma

Forty-four studies (81.5%) reported on correlates and/or effects of personal stigma. Among these, 24 examined associations with perceived or experienced stigma and 23 with self-stigma. Included articles were characterized by the heterogeneity of sample characteristics and methods. Sample size ranged from 35 to 1,229 participants (total n=8,132, mean n=185), mean age ranged from 24.5 (SD=6.3) to 64.7 (SD=8.7) years, and the percentage of male participants ranged between 39.7% and 100%. In 32 studies, male participants represented the majority. Most of the studies used a questionnaire design with one measurement date. Participants were recruited from all types of health care facilities, from rural and urban environments, and were in all stages and severity of disease. The majority of studies were carried out in Europe, North America, Australia and Asia, whereas no data reported on South-American or African populations.

In general, variables concerning the psychosocial functioning and general well-being of participants, such as quality of life, empowerment, self-esteem and self-efficacy, were inversely related to personal stigma in the majority of studies. Results showed that, of all the above-mentioned variables, quality of life was most thoroughly examined and was found to be inversely related to perceived/experienced stigma as well as to self-stigma in all studies addressing this relationship. Positive symptoms, depression (only perceived or experienced stigma) and general psychopathology were addressed in several studies and found to be associated with personal stigma in the majority of cases, whereas studies targeting attitudes, beliefs and personality of patients were rare, but produced mostly significant correlations 52,53.

Literacy (i.e., the ability to read and write) was related to perceived/experienced stigma in the only study measuring this relationship 52. Other socio-demographic variables were not associated with perceived/experienced stigma or self-stigma. This also applied to the treatment setting and to most of disease characteristics, including the duration of illness (perceived or experienced stigma only), lifetime number of hospitalizations, negative symptoms (perceived or experienced stigma only) and insight.

Finally, data were equivocal regarding the association of a number of variables with personal stigma. While age was not correlated with perceived/experienced stigma, results were contradictory concerning self-stigma. Karidi et al 34 found higher age to be negatively correlated with self-stigma, whereas other studies reported that higher age was associated with poor stigma resistance 54, more discrimination experience and more stigma-related withdrawal 49. Five of eight studies reported no association between age and self-stigma. Also male sex was found to be related to self-stigma in opposing directions 34,51. Older age of illness onset/first hospitalization was negatively correlated with perceived/experienced stigma in one of two studies 48. Findings regarding self-stigma and age of onset were contradictory, with one study reporting a positive association 34, one reporting a negative association 12 and two studies reporting no association. Furthermore, duration of illness (self-stigma only), negative symptoms (self-stigma only), depression (self-stigma only), treatment compliance (perceived or experienced stigma only) and social functioning (perceived or experienced stigma only) showed ambiguous associations with aspects of personal stigma (Table 4).

Table 4.

Level of the evidence of associations of specific variables with personal stigma

| Correlates of perceived/experienced stigmatization | Correlates of self-stigma | |

|---|---|---|

| Existing association | ||

| Risk factors (positive association) | Literacy 52 | Harm avoidance 53 |

| Relatives' perceived stigma 52 and evaluation of patient's stigma 52 | Positive symptoms 12,64,65 | |

| Belief that illness is a disease 52, due to karma 52 or evil spirit 52 | General psychopathology 34 | |

| Number of any 52 and of non-medical causal beliefs 52 | Social anxiety 66 | |

| Schizophrenia diagnosis 28,55 | Social avoidance 12 | |

| Positive symptoms 5,32,33,35,39,48,52,56,57 | Withdrawal as coping strategy 12 | |

| General psychopathology 33,35,48,56,57 | Insight in effect of medication 67 | |

| Depression 32,35,48,57–59 or guilt 62 | Discrimination experience 62 | |

| Social anxiety 60 | Emotional discomfort 64 | |

| Disability 33 | ||

| Coping strategy: withdrawal 35,57 or secrecy 35,57 | ||

| Discrimination experience 62 | ||

| Protective factors (negative association) | Social integration 32,58,61 | Self-directedness 53 and persistence 53 |

| Quality of life 32,48,55,58,59,61,63 | Social integration 64 and support 72 | |

| Empowerment 57,58 | Treatment compliance 67–70 | |

| Self-esteem 30,47,59 and self-efficacy 35,57 | Hope 65,71 and empowerment 58 | |

| Satisfaction with finances 32 | Quality of life 58,65,72,73 | |

| Support 63 | Self-esteem (12,54,47,49 | |

| Mastery 63 | Social 43,62 and vocational functioning 73 | |

| Recovery 62,74 | ||

| Lack of association | Being married 33,48,58 | Being married 58 |

| Living alone 48,58 | Living alone 58 | |

| Education 32,33,40,48 | Education 10,54,64,65,75 | |

| Age 33,35,48,52,56,58 | Lifetime number of hospitalizations 34,58,64,65 | |

| Male gender 5,32,33,35,40,48,52,58 | Diagnosis of schizophrenia 64 | |

| Ethnicity 5 | Insight 12 | |

| Residency 52 | Medication compliance 76 | |

| Employment 33,35,40,48,52 and income 32,41,52 | ||

| No. of systems of therapy used 52 | ||

| Hospital type 40,48 | ||

| Belief that illness is due to punishment by god 52, black magic 52 | ||

| Belief that illness should be treated by a doctor/hospital 52, traditional healer 52, mantravadi/shaman 52, be cured by going to a temple/place of worship 52 | ||

| Number of treatment beliefs 52 or non-medical treatment beliefs 52 | ||

| Duration of illness 48,58 | ||

| Lifetime number of hospitalization 48,58 | ||

| Negative symptoms 5,32,33,35,48,52,56 | ||

| Insight 32,35,40,74 | ||

| Mixed/unclear results | Age at onset/first hospitalization 48,58 | Age 10,34,49,54,58,64,65,75 |

| Treatment compliance 38,59 | Male gender 10,34,45,58 | |

| Social functioning 5,32,58,62 | Age at onset/first hospitalization 12,34,58,65 | |

| Duration of illness 34,58 | ||

| Depression 12,58 | ||

| Negative symptoms 64,65 |

Personal stigma as predictor of outcome

15 studies (27.8%) reported regression coefficients of perceived/experienced stigma (6 studies) and self-stigma (12 studies) as predictor variables for patient outcomes. Perceived/experienced stigma was found to predict higher depression, more social anxiety, more secrecy and withdrawal as coping strategies, along with lower quality of life, lower self-efficacy, lower self-esteem, lower social functioning, less support and less mastery. Self-stigma predicted more depression, more social anxiety, lower quality of life, less self-esteem, less social functioning, less hope, less vocational functioning, less recovery, less support and less treatment compliance (both attendance and participation subscales) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Personal stigma as predictor of outcome

| Perceived/ experienced stigma | Self-stigma |

|---|---|

| Depression 58 | Depression 58 |

| Social anxiety 60 | Social anxiety 66 |

| Withdrawal 35 | Quality of life 72 |

| Secrecy 35 | Self-esteem 12 |

| Quality of life 63 | Social functioning 43,62 |

| Social functioning 62 | Hope 71 |

| Self-efficacy 35 | Vocational functioning 73 |

| Self-esteem 77 | Recovery 75 |

| Support 63 | Support 72 |

| Mastery 63 | Treatment compliance: attendance 67 |

| Treatment compliance: participation 69 |

Additional results

Our literature search did not yield many studies reporting on or comparing data of patients in different stages of disease (i.e., in initial prodrome, first-episode, multi-episode schizophrenia). Only two studies reported explicitly on associations with personal stigma in first-episode psychosis 39,60. As in chronic samples, patients in the first episode showed increased perceived stigma when they had social anxiety 60. This does not differ from the results concerning the relationship of self-stigma and social anxiety in a sample of elderly patients with multiple illness episodes (mean age=64.7, SD=8.7) 66. Likewise, the results of the second sample of patients with first-episode psychosis concerned prevalence rates and the relationship between positive symptoms and perceived stigma 39, and they did not differ from results regarding patients in later disease stages 5,53,48.

Concerning interventions targeting personal stigma in particular, the search only yielded two trials. The first study found no effect on perceived discrimination of a 6-week group cognitive-behavioral therapy in 21 patients with schizophrenia followed for 18 weeks, but significant improvement of self-esteem 78. No control group was included. The second study, a randomized controlled trial, examined the effect of a 10-week culturally sensitive psychoeducational group program on the perception of stigma in 48 patients with schizophrenia and found a significant decrease in the perceived discrimination score and greater coping skills in the experimental group 79.

DISCUSSION

Results from this systematic review indicate that perceived and experienced stigma as well as self-stigma are phenomena concerning a high percentage of patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. An average of 64.5% of patients had perceived stigma, 55.9% actually had experienced stigma and 49.2% reported alienation (shame) as the most common aspect of self-stigma.

Socio-demographic variables are only marginally associated with personal stigma, although some evidence was found for a significant association with literacy. In contrast, it is rather evident that psychosocial factors such as quality of life are inversely associated with personal stigma. The picture concerning illness-related variables is rather equivocal. On the one hand, age of onset, duration of illness and lifetime number of hospitalizations showed few significant or contradictory associations with personal stigma and need to be examined further. On the other hand, positive symptoms, depression and general psychopathology were mostly found to correlate significantly with personal stigma. However, no illness-related variable was unequivocally correlated with personal stigma, except for social anxiety, which was only assessed in two studies, one on perceived stigma 60 and one on self-stigma 66. These results are in line with another study that was excluded from our review due to the heterogeneity of its sample 80. However, the association of depression and social anxiety with personal stigma may be an artifact in the sense that depressed people tend to perceive the reactions of their social environment in a negative way. In this case, the perception of stigmatization would be a symptom of the underlying pathology rather than an independent variable.

We were not able to identify a single study addressing differences concerning the impact of personal stigma on patients in different stages of the illness. The only two studies 39,60 explicitly examining samples of first-episode patients reported results that were similar to those in chronically ill cohorts. However, these observations cannot replace quantitative group comparisons. Thus, the evolution and effects of personal stigma in early illness phases remain an important open research question, particularly given the current focus on early identification and prevention of schizophrenia spectrum disorders and the concerns regarding the public and, especially, personal stigmatization of adolescents and young adults who may be given the label of a disorder they might never develop. Such research is especially pressing, given the introduction of the attenuated psychosis syndrome in Section 3 of DSM-5 81.

The literature search identified only two studies focusing on the development or evaluation of interventions aimed at reducing personal stigma in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. On the one hand, this is surprising, given the large amount of research on intra- and interpersonal variables modifying personal stigma and on its adverse effects, which could guide the development of such interventions. In fact, many studies included in this review discussed the implications of their findings for the development of therapeutic interventions 30. This is in contrast to numerous interventions aimed at reducing public stigma 6,7. On the other hand, our focus on samples with schizophrenia spectrum disorders may have excluded studies conducted in more general samples of mentally ill people. In addition, we may have missed studies that targeted stigma indirectly without explicitly mentioning it. Nevertheless, the lack of interventions targeting personal stigma is striking. Hence, although psychosocial interventions frequently include the general topic of public and personal stigma in psychoeducational and other intervention techniques, the results of this review emphasize the need for interventions more specifically targeting stigma acceptance and incorporation by patients and the increase of stigma resistance among patients. This is especially relevant since the success of anti-stigma initiatives aimed to reduce public stigma has been quite limited 82,83. By contrast, one pilot study in individuals at clinically elevated risk for psychosis suggested that general psychoeducation can help reduce self-stigma, which in that study was not a primary focus 84.

The findings of this review have to be interpreted within its limitations. These include the small sample sizes in a number of the included studies, the use of diverse designs and rating scales, and the selection of often highly heterogeneous outcome and predictor variables. Moreover, comparison groups were generally not available, precluding an assessment of the specificity or quantitative differences of the findings in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders compared to other mental disorders.

In summary, perceived and experienced stigma, as well as self-stigma, are frequent in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Ten years after Link and Phelan called for the development of “multifaceted multilevel interventions” to produce “real change” 21 in stigma-related processes, the requested descriptive research on underlying factors and characteristics to inform the development of such interventions has been done. The practical implementation of these interventions, however, is the next important step, seeking to optimize outcomes through better social integration and functioning. It is hoped that the next decade will see major strides in this direction.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the Zucker Hillside Hospital Mental Advanced Center for Intervention and Services Research for the Study of Schizophrenia grant (MH090590) from the National Institute of Mental Health.

References

- 1.Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. The stigma of mental illness in Germany: a trend analysis. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2005;51:276–84. doi: 10.1177/0020764005057390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corrigan PW, Penn DL. Lessons from social psychology on discrediting psychiatric stigma. Am Psychol. 1999;54:765–76. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.9.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, et al. Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1328–33. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corrigan PW, Lurie BD, Goldman HH, et al. How adolescents perceive the stigma of mental illness and alcohol abuse. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:544–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.5.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penn DL, Kohlmaier JR, Corrigan PW. Interpersonal factors contributing to the stigma of schizophrenia: social skills, perceived attractiveness, and symptoms. Schizophr Res. 2000;45:37–45. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penn DL, Kommana S, Mansfield M, et al. Dispelling the stigma of schizophrenia: II. The impact of information on dangerousness. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:437–46. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rusch N, Angermeyer MC, Corrigan PW. Mental illness stigma: concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:529–39. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mueller B, Nordt C, Lauber C, et al. Social support modifies perceived stigmatization in the first years of mental illness: a longitudinal approach. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corrigan PW. Empowerment and serious mental illness: treatment partnerships and community opportunities. Psychiatr Q. 2002;73:217–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1016040805432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mak WW, Wu CF. Cognitive insight and causal attribution in the development of self-stigma among individuals with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:1800–2. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.12.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCann TV, Clark E. Advancing self-determination with young adults who have schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2004;11:12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2004.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yanos PT, Roe D, Markus K, et al. Pathways between internalized stigma and outcomes related to recovery in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:1437–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.12.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ben-Zeev D, Young MA, Corrigan PW. DSM-V and the stigma of mental illness. J Ment Health. 2010;19:318–27. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2010.492484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corcoran CM, First MB, Cornblatt B. The psychosis risk syndrome and its proposed inclusion in the DSM-V: a risk–benefit analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010;120:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linscott RJ, Cross FV. The burden of awareness of psychometric risk for schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2009;166:184–91. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang LH, Wonpat-Borja AJ, Opler MG, et al. Potential stigma associated with inclusion of the psychosis risk syndrome in the DSM-V: an empirical question. Schizophr Res. 2010;120:42–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:28–37. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klosterkotter J, Schultze-Lutter F, Bechdolf A, et al. Prediction and prevention of schizophrenia: what has been achieved and where to go next? World Psychiatry. 2011;10:165–74. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruhrmann S, Schultze-Lutter F, Maier W, et al. Pharmacological intervention in the initial prodromal phase of psychosis. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–85. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corrigan PA, Watson AC, Barr L. The self-stigma of mental illness: implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2006;25:875–84. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lebel T. Perceptions of and responses to stigma. Sociol Comp. 2008;2:409–32. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corrigan PW, Watson AC. Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry. 2002;1:16–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brohan E, Slade M, Clement S, et al. Experiences of mental illness stigma, prejudice and discrimination: a review of measures. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:80–91. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Link BG, Yang LH, Phelan JC, et al. Measuring mental illness stigma. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30:511–41. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrison J, Gill A. The experience and consequences of people with mental health problems, the impact of stigma upon people with schizophrenia: a way forward. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2010;17:242–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angermeyer MC, Beck M, Dietrich S, et al. The stigma of mental illness: patients' anticipations and experiences. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2004;50:153–62. doi: 10.1177/0020764004043115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luchins DJ. At issue: will the term brain disease reduce stigma and promote parity for mental illnesses? Schizophr Bull. 2004;30:1043–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berge M, Ranney M. Self-esteem and stigma among persons with schizophrenia: implications for mental health. Care Manag J. 2005;6:139–44. doi: 10.1891/cmaj.6.3.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cechnicki A, Angermeyer MC, Bielanska A. Anticipated and experienced stigma among people with schizophrenia: its nature and correlates. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46:643–50. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dickerson FB, Sommerville J, Origoni AE, et al. Experiences of stigma among outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28:143–55. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ertugrul A, Ulug B. Perception of stigma among patients with schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:73–7. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karidi MV, Stefanis CN, Theleritis C, et al. Perceived social stigma, self-concept, and self-stigmatization of patient with schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51:19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kleim B, Vauth R, Adam G, et al. Perceived stigma predicts low self-efficacy and poor coping in schizophrenia. J Mental Health. 2008;17:482–91. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lai YM, Hong CP, Chee CY. Stigma of mental illness. Singapore Med J. 2001;42:111–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee S, Lee MT, Chiu MY, et al. Experience of social stigma by people with schizophrenia in Hong Kong. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:153–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCann TV, Boardman G, Clark E, et al. Risk profiles for non-adherence to antipsychotic medications. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2008;15:622–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2008.01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tarrier N, Khan S, Cater J, et al. The subjective consequences of suffering a first episode psychosis: trauma and suicide behaviour. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:29–35. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thornicroft G, Brohan E, Rose D, et al. Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2009;373:408–15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61817-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baldwin ML, Marcus SC. Perceived and measured stigma among workers with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:388–92. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Botha UA, Koen L, Niehaus DJ. Perceptions of a South African schizophrenia population with regards to community attitudes towards their illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:619–23. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brohan E, Elgie R, Sartorius N, et al. Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with schizophrenia in 14 European countries: the GAMIAN-Europe study. Schizophr Res. 2010;122:232–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chee CY, Ng TP, Kua EH. Comparing the stigma of mental illness in a general hospital with a state mental hospital: a Singapore study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:648–53. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0932-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jenkins JH, Carpenter-Song EA. Awareness of stigma among persons with schizophrenia: marking the contexts of lived experience. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197:520–9. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181aad5e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loganathan S, Murthy SR. Experiences of stigma and discrimination endured by people suffering from schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50:39–46. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.39758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sibitz I, Unger A, Woppmann A, et al. Stigma resistance in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;37:316–23. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Switaj P, Wciorka J, Smolarska-Switaj J, et al. Extent and predictors of stigma experienced by patients with schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2009;24:513–20. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Werner P, Aviv A, Barak Y. Self-stigma, self-esteem and age in persons with schizophrenia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008;20:174–87. doi: 10.1017/S1041610207005340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee S, Chiu MY, Tsang A, et al. Stigmatizing experience and structural discrimination associated with the treatment of schizophrenia in Hong Kong. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:1685–96. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jenkins JH, Carpenter-Song EA. Stigma despite recovery: strategies for living in the aftermath of psychosis. Med Anthropol Q. 2008;22:381–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2008.00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Charles H, Manoranjitham SD, Jacob KS. Stigma and explanatory models among people with schizophrenia and their relatives in Vellore, South India. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2007;53:325–32. doi: 10.1177/0020764006074538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Margetic BA, Jakovljevic M, Ivanec D, et al. Relations of internalized stigma with temperament and character in patients with schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51:603–6. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lysaker PH, Tsai J, Yanos P, et al. Associations of multiple domains of self-esteem with four dimensions of stigma in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lundberg B, Hansson L, Wentz E, et al. Are stigma experiences among persons with mental illness, related to perceptions of self-esteem, empowerment and sense of coherence? J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2009;16:516–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Margetic B, Aukst-Margetic B, Ivanec D, et al. Perception of stigmatization in forensic patients with schizophrenia. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008;54:502–13. doi: 10.1177/0020764008090842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vauth R, Kleim B, Wirtz M, et al. Self-efficacy and empowerment as outcomes of self-stigmatizing and coping in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2007;150:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sibitz I, Amering M, Unger A, et al. The impact of the social network, stigma and empowerment on the quality of life in patients with schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Staring AB, Van der Gaag M, Van den Berge M, et al. Stigma moderates the associations of insight with depressed mood, low self-esteem, and low quality of life in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Res. 2009;115:363–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Birchwood M, Trower P, Brunet K, et al. Social anxiety and the shame of psychosis: a study in first episode psychosis. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1025–37. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mechanic D, McAlpine D, Rosenfield S, et al. Effects of illness attribution and depression on the quality of life among persons with serious mental illness. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:155–64. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Munoz M, Sanz M, Perez-Santos E, et al. Proposal of a socio-cognitive-behavioral structural equation model of internalized stigma in people with severe and persistent mental illness. Psychiatry Res. 2010;186:402–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hsiung PC, Pan AW, Liu SK, et al. Mastery and stigma in predicting the subjective quality of life of patients with schizophrenia in Taiwan. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:494–500. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e4d310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lysaker PH, Davis LW, Warman DM, et al. Stigma, social function and symptoms in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: associations across 6 months. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lysaker PH, Roe D, Yanos PT. Toward understanding the insight paradox: internalized stigma moderates the association between insight and social functioning, hope, and self-esteem among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:192–9. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lysaker PH, Yanos PT, Outcalt J, et al. Association of stigma, self-esteem, and symptoms with concurrent and prospective assessment of social anxiety in schizophrenia. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2010;4:41–8. doi: 10.3371/CSRP.4.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fung KM, Tsang HW, Chan F. Self-stigma, stages of change and psychosocial treatment adherence among Chinese people with schizophrenia: a path analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45:561–8. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0098-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fung KM, Tsang HW, Corrigan PW. Self-stigma of people with schizophrenia as predictor of their adherence to psychosocial treatment. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2008;32:95–104. doi: 10.2975/32.2.2008.95.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tsang HW, Fung KM, Chung RC. Self-stigma and stages of change as predictors of treatment adherence of individuals with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2010;180:10–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tsang HW, Fung KM, Corrigan PW. Psychosocial treatment compliance scale for people with psychotic disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40:561–9. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lysaker PH, Salyers MP, Tsai J, et al. Clinical and psychological correlates of two domains of hopelessness in schizophrenia. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008;45:911–9. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2007.07.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ho WW, Chiu MY, Lo WT, et al. Recovery components as determinants of the health-related quality of life among patients with schizophrenia: structural equation modelling analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44:71–84. doi: 10.3109/00048670903393654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yanos PT, Lysaker PH, Roe D. Internalized stigma as a barrier to improvement in vocational functioning among people with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:211–3. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pyne JM, Bean D, Sullivan G. Characteristics of patients with schizophrenia who do not believe they are mentally ill. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189:146–53. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200103000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lysaker PH, Buck KD, Taylor AC, et al. Associations of metacognition and internalized stigma with quantitative assessments of self-experience in narratives of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2008;157:31–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tsang HW, Fung KM, Corrigan PW. Psychosocial and socio-demographic correlates of medication compliance among people with schizophrenia. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2009;40:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Link BG, Struening EL, Neese-Todd S, et al. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: the consequences of stigma for the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1621–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Knight MTD, Wykes T, Hayward P. Group treatment of perceived stigma and self-esteem in schizophrenia: a waiting list trial of efficacy. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2006;34:305–18. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shin SK, Lukens EP. Effects of psychoeducation for Korean Americans with chronic mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1125–31. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.9.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rusch N, Corrigan PW, Powell K, et al. A stress-coping model of mental illness stigma: II. Emotional stress responses, coping behavior and outcome. Schizophr Res. 2009;110:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Correll CU, Hauser M, Auther AM, et al. Research in people with psychosis risk syndrome: a review of the current evidence and future directions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51:390–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gaebel W, Zaske H, Baumann AE, et al. Evaluation of the German WPA "Program against stigma and discrimination because of schizophrenia – Open the Doors": results from representative telephone surveys before and after three years of antistigma interventions. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:184–93. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rosen A, Walter G, Casey D, et al. Combatting psychiatric stigma: an overview of contemporary initiatives. Australas Psychiatry. 2000;8:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hauser M, Lautenschläger M, Gudlowski Y, et al. Psychoeducation with patients at-risk for schizophrenia – an exploratory pilot study. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76:138–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]