Abstract

Somatostatin was discovered four decades ago and since then its physiological role has been extensively investigated, first in relation with its inhibitory effect on growth hormone secretion but soon it expanded to extrapituitary actions influencing various stress-responsive systems. Somatostatin is expressed in distinct brain nuclei and binds to five somatostatin receptor subtypes which are also widely expressed in the brain with a distinct distribution pattern. The last few years witnessed the discovery of highly selective peptide somatostatin receptor agonists and antagonists representing valuable tools to delineate the respective pathways of somatostatin signaling. Here we review the centrally mediated actions of somatostatin and related selective somatostatin receptor subtype agonists to influence the endocrine, autonomic, and visceral components of the stress response and basal behavior as well as thermogenesis.

Keywords: Autonomic nervous system, fecal pellet output, food intake, gastrointestinal motility, octreotide, ODT8-SST, thermogenesis

1. INTRODUCTION

Guillemin and colleagues reported in 1973 the isolation of somatostatin-14 out of 490,000 ovine hypothalami using the ability of the extracts to inhibit growth hormone (GH) secretion from cultured pituitary cells [1]. Seven years later, the French group of Ribet and coworkers published the primary structure of the N terminally extended form, somatostatin-28 from porcine intestine [2]. Ground work to identify somatostatin receptors has led to the identification and characterization of five subtypes (sst1–5) [3]. In addition to the initially established GH inhibiting physiological action of somatostatin which is also reflected in its name, several other extrapituitary actions of the peptide were soon described including its influence on parasympathetic and sympathetic outflow resulting in changes of adrenal epinephrine secretion, heart rate, blood pressure, and gastric acid secretion [4]. The last three decades have witnessed a tremendous increase in the understanding of this peptide’s physiological role and mechanisms of actions, greatly attributed to new pharmacological tools developed to probe the respective role of somatostatin receptor subtypes. This review is focused on the centrally mediated actions of somatostatin and selective agonists on the modulation of stress-related behavioral, endocrine, autonomic and visceral responses as well as thermogenesis.

2. BRAIN SOMATOSTATIN AND ITS RECEPTORS

2.1. Distribution of Somatostatin and its Receptors

Somatostatin is widely distributed in the brain except in the cerebellum [5, 6]. Immunohistochemical mapping of brain somatostatin distribution showed that the peptide is highly expressed in the deep cortex, limbic structures, the central nucleus of the amygdala, sensory systems, the hypothalamus and the periaqueductal central gray [5–7]. Within the hypothalamus, somatostatin is predominantly expressed in the periventricular subdivision of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and in lower densities also in the arcuate nucleus, ventromedial nucleus, and parvocellular subdivision of the PVN [5, 6].

Similar to the ligand, somatostatin receptor genes are widely expressed in the rat brain including predominantly deeper layers of the cerebral cortex (sst1 > sst2 = sst3 > sst4), bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (sst2 > sst1 > sst4), basolateral amygdaloid nucleus (sst2 > sst1 = sst3 > sst4), medial amygdaloid nucleus (sst3 > sst1 = sst2), paraventricular thalamic nucleus (sst2 and sst3), medial preoptic nucleus (sst4 > sst3 = sst1), PVN (sst2 = sst3), dorsomedial hypothalamic nucleus (sst1 = sst3), ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (sst1 > sst3 > sst2), arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (sst1 = sst2 = sst3 > sst4), substantia nigra (sst3 > sst1), dorsal raphe nucleus (sst1 = sst2 = sst3), granular layer of the cerebellum (sst3 > sst5 > sst2 > sst1 = sst4), locus coeruleus (sst2 > sst3), nucleus of the solitary tract (sst1 = sst2 > sst3) and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve (sst2 = sst4 > sst5) [8, 9] providing anatomical support for somatostatin signaling being involved in multiple regulatory pathways.

2.2. Fos Expression Induced by Activation of Somatostatin Receptors

The immediate early gene c-fos is a well established marker of neuronal activation [10, 11]. It has been extensively used over the past two decades to investigate changes in patterns of brain activation following injection of various peptides or changes in external or internal environment [10, 12]. Somatostatin injected at a low dose intracerebroventricularly (icv) increased Fos expression in the supraoptic nucleus, the PVN, and in the subfornical organ [13] whereas after high doses (10 μg, icv), known to induce barrel rotation, c-fos gene expression was detected in the piriform cortex and the lingula, uvula, nodulus, pars simplex, pars centralis, and culmen lobules of the cerebellum [14]. A recent study investigated the Fos expression pattern following icv injection of ODT8-SST, a pan-somatostatin agonist, and the selective sst2 peptide agonist, des-AA1,4–6,11–13-[DPhe2,Aph7(Cbm),DTrp8]-Cbm-SST-Thr-NH2 [15] in rats. Results showed that both peptides stimulated Fos expression in the somatosensory and -motor cortex, striatum, basolateral amygdaloid nucleus, ventral premamillary nucleus, PVN, arcuate nucleus, supraoptic nucleus, parasubthalamic nucleus, cerebellum, external lateral parabrachial nucleus, medullary reticular nucleus, inferior olivary nucleus, and the superficial layer of the caudal spinal trigeminal nucleus with Fos expression being less pronounced following ODT8-SST than after the sst2 agonist [16]. This difference could be attributed to different receptor binding affinities (ODT8-SST displays lower affinity to the sst2 receptor than the selective sst2 agonist [IC50 binding affinity of the sst2 agonist to the sst2 receptor: 7.5–20 nM [15] compared to 41.0 ± 8.7 nM for ODT8-SST [17]). The affinity of ODT8-SST to other receptor subtypes in addition to the sst2 [17] may also play a role since electro-physiological studies showed that somatostatin inhibits neuronal activity in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus [18], locus coeruleus [19] and periaqueductal gray [20]. In addition, the sst2, sst3, and sst5 agonist, octreotide blunts the expression of Fos in the spinal trigeminal nucleus stimulated by corneal manipulation [21]. These brain sites responsive to somatostatin agonists will be described in the next paragraphs in the context of the central effects exerted by somatostatin.

2.3. Regulation of Somatostatin and its Receptors by Stress and Glucocorticoids

Early on, the expression of somatostatin and its receptors has been investigated under several conditions of stress. Data are consistent with somatostatin expression being altered in animals exposed to stress along with the activation of somatostatin signaling pathways within specific brain nuclei. Acute immobilization stress increased somatostatin mRNA levels in the periventricular part of the PVN [22] and decreased the peptide content in hypothalamic (supraoptic nucleus, PVN) and extrahypothalamic areas such as the locus coeruleus and nucleus of the solitary tract in rats [22, 23]. Similarly, rats exposed to broad band noise (102 dB) had decreased somatostatin immunoreactivity in the hypothalamus, whereas levels in the amygdala were increased [24]. Handling and thereby disturbing the rats’ environment increased somatostatin release from the median eminence which was further stimulated by a nociceptive stimulus [25] or immobilization stress and associated with a decrease in plasma GH levels [26]. Other studies showed that somatostatin expression was lower in the periventricular part of the PVN and stalk-median eminence in a rat model of depression which was associated with elevated plasma levels of GH [27]. In contrast, mild footshock stress did not alter somatostatin-like immunoreactivity in the dopaminergic ventral tegmental area [28].

Changes in somatostatin induced by various stressors are likely to be modulated by glucocorticoids. Intraperitoneal (ip) injection of dexamethasone (300 μg/100 g body weight) stimulated the hypothalamic release of somatostatin in rats, an effect completely abolished by ip injection of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, MK-801 [29]. In addition, somatostatin mRNA in dentate gyrus hilar cells is stimulated by ip injection of dexamethasone (300 μg/100 g body weight) [30]. Further underlining the importance of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal gland glucocorticoid signaling system in the modulation of brain somatostatin following stress, in adrenalectomized rats no change in hypothalamic somatostatin levels was observed following immobilization stress [31]. In addition, adrenalectomized rats displayed increased somatostatin mRNA expression in hypothalamic neurons and somatostatin levels in the median eminence which were decreased by injection of dexamethasone [32, 33] pointing towards an inhibitory tone of glucocorticoids on somatostatin signaling under baseline conditions which differs from the stimulatory action of glucocorticoids on somatostatin under conditions of stress.

At the receptor level, predator stress (exposure of rats to a ferret) increased sst2 mRNA expression in the amygdala and the anterior cingulate cortex which was associated with behavioral signs of anxiety [34].

3. CENTRAL ACTIONS OF SOMATOSTATIN OR AGONISTS TO INFLUENCE COMPONENTS OF THE STRESS RESPONSE

3.1. Endocrine Responses

3.1.1. Oligo-somatostatin Agonists Prevent Stress-related Stimulation of Adrenocorticotropic Hormone

Somatostatin was early on shown to be involved in the modulation of the stress response. When injected icv in rats somatostatin-28 inhibits the tail suspension stress-induced increase of circulating adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), an effect mimicked by the pan-somatostatin agonist, ODT8-SST but not by somatostatin-14 [35]. This inhibitory effect on stress-stimulated ACTH release was also observed in a different species (sheep) using the oligo-somatostatin agonist, cyclo-(N-Me-Ala-Tyr-D-Trp-Lys-Val-Phe) under conditions of hemorrhage [36]. By contrast, ODT8-SST did not modify ACTH secretion induced by icv injection of CRF pointing towards an inhibition of CRF release by somatostatin under conditions of stress [35]. In sst2 receptor knockout mice compared to wild type mice, ACTH release assessed in vitro was greatly increased [37] indicating a prominent role of this receptor subtype in the basal regulation of a key hormone of the endocrine response to stress. Interestingly, when injected intravenously (iv) in rats, somatostatin-28 had no effect, further indicating a central site of action [35].

3.1.2. Somatostatin is Involved in Stress-related Inhibition of Growth Hormone Secretion

In contrast to the counter regulatory action of brain somatosatin-28 on the stress-related stimulation of hypothalamic-pituitary CRF-ACTH release, brain somatostatin mediates the inhibition of GH observed under stress conditions. This was supported by the decrease in GH secretion induced by CRF injected icv whereas iv injection did not [38]. In addition, the CRF induced suppression of GH was blocked by injection of anti-somatostatin antiserum. The icv injection of a CRF receptor antagonist also blocked the lowering of plasma GH levels induced by electroshocks in rats [38, 39]. Further studies established that the downstream action of somastostatin involves the inhibition of growth hormone releasing hormone as shown under conditions of ether stress-induced GH suppression [40].

3.2. Autonomic Responses

3.2.1. Oligo-somatostatin Agonists Prevent Stress-related Activation of Sympathetic Nervous System

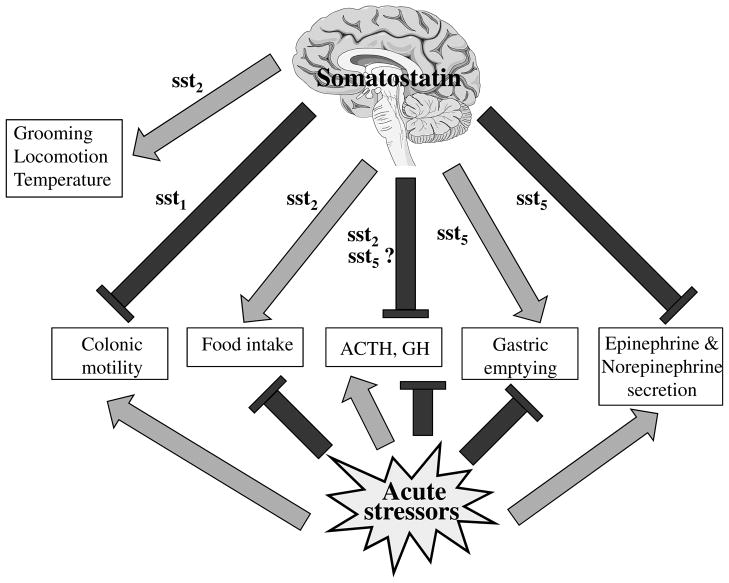

The pan-somatostatin agonist, ODT8-SST has been tested in various paradigms of stress, using either metabolic (insulin induced hypoglycemia) or psychological (noise) stressors and shown to suppress the rise in plasma epinephrine and norepinephrine following icv injection while iv injection had no effect in rats [41]. Similarly, somatostatin-28 inhibited stress-related adrenomedullary epinephrine secretion in rats whereas somatostatin-14 did not [35]. This may indicate a prominent role of the sst5 mediating these actions based on the higher binding affinity of somatostatin-28 for this receptor subtype compared that of somatostatin-14 [42, 43] which is still to be further ascertained (Fig. 1). Interestingly, the inhibitory effect of ODT8-SST on epinephrine was more pronounced than that on plasma norepinephrine [41]. Likewise, ODT8-SST and somatostatin-28 injected into the brain prevented the icv bombesin induced increase of plasma epinephrine levels [43, 44]. A similar inhibitory effect on icv carbachol-induced increased plasma epinephrine levels was reproduced in dogs by icv pretreatment with ODT8-SST [45]. The physiological relevance of these findings is underlined by the observation that depletion of endogenous somatostatin by cysteamine increases adrenal epinephrine secretion [46] which is reversed by brain injection of somatostatin [47] or ODT8-SST [48] indicating a basal inhibitory tone of brain somatostatin on adrenal catecholamine production. Consistent with these findings electrophysiological studies showed the suppression of adrenal sympathetic activity after icv injection of somatostatin in rats [49]. In addition, transneural tracing cell body labeling combined with immunohistochemistry provided neuroanatomical support for somatostatinergic regulation of sympathoadrenal preganglionic neurons. Somatostatin positive cells were detected in virally infected neurons by retrograde pseudorabies virus injected in the rat adrenal medulla [50]. Those double labeled neurons were mainly observed in the medulla oblongata within the raphe pallidus, raphe obscurus, ventromedial medulla and A5 neurons along with few neurons in the PVN [50]. In addition, multiple somatostatin receptor subtypes, possibly combined as heterodimers, are expressed in rat medulla oblongata at sites regulating autonomic activity [9].

Fig. 1.

Acute stress-induced endocrine (stimulation of ACTH, inhibition of GH), behavioral (reduction of food intake), autonomic (stimulation of sympathetic outflow) and visceral (delayed gastric emptying and stimulation of propulsive colonic motor function) alterations. These responses are all antagonized by central injection of somatostatin agonists except the stress-related suppression of GH which is mediated by hypothalamic somatostatin. Differential somatostatin receptor subtypes are involved in the various anti-stress responses. Light gray: stimulation, black: inhibition.

3.2.2. Somatostatin Agonists Influence Parasympathetic Signaling Dependent on the Brain Sites of Injection

Since the mRNA of various sst receptors is expressed in the brainstem, namely the sst1, sst2, sst4, and sst5 in the nucleus of the solitary tract and sst2, sst4, and sst5 in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve which also contained acetylcholine [9], studies investigated the effects of somatostatin agonists on parasympathetic signaling. One well established visceral parameter responsive to changes in vagal activity is gastric acid secretion [51]. Injection of the pan-somatostatin agonist, ODT8-SST [52] or the oligosomatostatin agonist, octreotide [53] at the level of the brainstem into the cisterna magna (ic) increased the volume and the acid output of gastric secretion in rats. Similarly, octreotide unilaterally microinjected into the dorsal vagal complex increased gastric acid secretion in urethane anesthetized rats [53, 54], whereas injection into the surrounding area had no effect [54]. By contrast, when octreotide was injected at the level of the forebrain into the lateral brain ventricle (icv) or directly into the hypothalamus (into the PVN or lateral hypothalamus) the pentagastrin-stimulated gastric acid secretion was inhibited [54] indicating differential effects of sst activation dependent on the fore or hind brain targeted.

Studies investigating the sst receptor subtype(s) involved in the brainstem showed that ic injection of the sst3 agonist, BIM-23056 increased, whereas the sst2 agonist, DC 32-87 decreased basal acid secretion and ic injection of somatostatin-14 and the sst5 agonist, BIM-23052 had no effect on gastric acid output in conscious rats equipped with chronic gastric and ic cannulae [55]. In the forebrain, in line with the icv and hypothalamic microinjection studies of octreotide, somatostatin-14 and the sst5 agonist, BIM-23052 injected icv also inhibited gastric acid secretion [56]. The sst2 agonist, DC 32-87 and the sst3 agonist, BIM-23056 injected icv alone did not alter gastric acid secretion, whereas icv co-injection of the sst2 agonist and a subthreshold dose of the sst5 agonist reduced gastric acid secretion [56]. In contrast, iv injection of both peptides had no effect [52] or higher doses of octreotide inhibited gastric acid secretion in conscious pylorus-ligated rats [53]. Octreotide injected ic also increased the levels of histamine in the portal blood whereas plasma levels of gastrin were not altered [53]. The effect on gastric acid secretion was completely abolished by vagotomy [54] or systemic injection of atropine [52] indicating a brainstem sst3-mediated vagal mode of action to stimulate gastric acid output and a sst5-mediated forebrain action to inhibit gastric acid secretion.

3.3. Visceral Responses

3.3.1. Oligo-somatostatin Agonists Stimulate Basal Gastric Emptying and Prevent Stress-related Gastric Ileus

Previous studies showed that the pan-somatostatin agonist, ODT8-SST injected into the cisterna magna accelerates gastric emptying of a liquid non-nutrient solution in rats, an effect that was reproduced by somatostatin-28 but not somatostatin-14 or the agonists preferring sst1, CH-275, sst2, DC-32-87, sst3, BIM-23056 and sst4, L-803,087 [57]. This and the observation that an sst5 preferring agonist, BIM-23052, stimulates gastric emptying underline the importance of this receptor subtype in mediating the gastroprokinetic effects [57]. These findings are in line with the prominent expression of sst5 in the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve [9, 58]. Similar to the injection at the level of the brainstem, icv injection of ODT8-SST stimulates gastric emptying of a solid meal in rats [59] and mice [60], whereas a selective peptide sst2 agonist had no effect [61]. By contrast, the peripheral injection of BIM-23052 [57] or ODT8-SST [59] did not modify gastric emptying supporting a centrally mediated action of peptides injected into the cerebrospinal fluid. The sst5 agonist, BIM-23052 injected intracisternally-induced stimulation of basal gastric emptying was prevented by subdiaphragmatic vagotomy or atropine [57] indicating a neural pathway involving vagal cholinergic activation. In addition, the ic injection of ODT8-SST or the sst5 preferring agonist, BIM-23052 counteracting action on stress-related inhibition of gastric emptying was demonstrated under conditions of surgical stress (a.k.a. postoperative gastric ileus). The delayed gastric emptying induced by abdominal incision and cecal manipulation was completely restored to levels observed in sham operated (anesthesia alone) rats [62]. This points towards a prominent role of the sst5 (Fig. 1). However, it cannot be ruled out that a combined interaction also involves other somatostatin receptors since the sst5 forms heterodimers with the sst1 or sst2 resulting in a 50- and 10-fold increased signaling efficiency [63]. Of relevance, the decreased levels of the circulating prokinetic gastric hormone, ghrelin induced by abdominal surgery was prevented by ic injection of ODT8-SST [62]. However, this inhibitory action on ghrelin release is not the main mechanism of ic ODT8-SST induced prevention of gastric ileus since in the presence of blocked ghrelin signaling by peripheral injection of the ghrelin receptor antagonist, [D-Lys3]-GHRP-6, the gastroprokinetic action of ic ODT8-SST is still present [62]. Collectively, these data [57, 62] support a direct stimulation of gastric vagal cholinergic pathways on gastric myenteric neurons by ic ODT8-SST which will need to be further assessed.

3.3.2. Oligo-somatostatin Agonists Prevent Stress-related Stimulation of Colonic Function

Since sst receptors are expressed on the protein level in brain nuclei regulating colonic functions [64–66] such as the PVN (sst2–4), arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (sst1–5) and the locus coeruleus (sst2–4) [8, 67], the effect of somatostatin and sst agonists on stress-related stimulation of propulsive colonic functions was recently investigated. Stressing mice by short exposure to anesthesia vapor and icv injection of vehicle stimulates propulsive colonic motility as indicated by 99% increase in fecal pellet output, a response completely blocked by icv injection of ODT8-SST [60]. In addition, somatostatin-28 or the selective sst1 agonist induced a similar inhibitory response whereas selective peptide sst2 or sst4 agonist or the widely used oligo-somatostatin agonist, octreotide (sst2 > sst5 > sst3), had no effect [60] suggesting a prominent role for the sst1 in the mediation of the observed effects (Fig. 1). Likewise, the increased fecal pellet output induced by the icv injection of CRF or 1-h exposure to water avoidance stress in mice known to be mediated by activation of CRF signaling pathways [68] was robustly inhibited by brain injection of ODT8-SST. In line with findings on defecation, ODT8-SST injected icv reduced the contractile activity in the distal colon stimulated by exposing mice to semi-restraint conditions [60]. By contrast, the stimulation of the colonic secretomotor response to ip injected 5-hydroxytryptophan involving a direct 5-HT4 receptor mediated activation of colonic myenteric neurons in mice [69], was not affected by ODT8-SST [60]. Taken together, these findings support the contention that activation of brain sst1 receptors counteracts stress-related stimulation of colonic motor function most likely by suppressing CRF-related mechanisms involved in these colonic alterations (Fig. 1).

3.4. Behavioral Responses

3.4.1. Somatostatin and Agonists Induce Stereotypic Behaviors and Locomotor Activity

Brain injection of somatostatin was shown to influence various parameters of behavior with a dual mode of action dependent on the dose: activation of sniffing and exploratory behaviors following low doses (< 1 μg/rat) and after higher doses (1 – 10 μg/rat) a short increase of these behaviors was followed by a decrease [70]. Moreover, higher doses (> 3 μg/rat) of centrally injected somatostatin induce a specific type of abnormal behavior known as barrel rotations [14, 71]. A recent study extended these observations and reported an increase in grooming behavior following icv injection of ODT8-SST (1 μg/rat) in rats, while locomotor activity was not altered when assessed either manually or using an automated monitoring device [59]. Similarly, a selective sst2 agonist injected icv under the same experimental conditions also increased grooming behavior and additionally stimulated locomotor activity in rats [61]. The physiological involvement of sst2 signaling in the regulation of locomotion is indicated by the finding of reduced locomotor and exploratory activity in sst2 knockout mice [37, 72]. The increase in grooming and locomotion may represent a night time behavior of the nocturnal rats in line with the finding that somatostatin is involved in the entrainment of circadian clocks in the suprachiasmatic nucleus [73].

3.4.2. Oligo-somatostatin Agonists Stimulate Basal Feeding Behavior and Prevent Stress-related Anorexia

Early on, studies reported that somatostatin injected into the brain alters food intake although this has yielded inconsistent results including an orexigenic [74–79], anorexigenic [75, 77, 80], or biphasic effect [81]. These differences are likely related to the doses used with a stimulation of feeding following low picomolar doses and an inhibition following higher nanomolar doses injected icv in rats [77, 80]. It may be speculated that high doses injected into the brain also reached the circulation [82] to exert an inhibitory effect on feeding, possibly via a reduction of the orexigenic hormone ghrelin [83, 84]. In addition, at higher doses, changes in behavior (barrel rotation, or excessive grooming, locomotor activity) may interfere with the feeding behavior. A recent study reported that the pan-somatostatin agonist, ODT8-SST injected at 1 μg/rat icv stimulates food intake in rats under basal as well as already stimulated conditions during the dark phase whereas ip injection had no effect even at up to 1000-times higher doses, indicating a central site of action [59]. This food intake response was blocked by the neuropeptide Y (NPY) Y1 receptor antagonist, BIBP-3226 and the μ-opioid receptor antagonist, naloxone consistent with the orexigenic NPY-reward (naloxone dependent) feeding circuitry [85]. Alternatively, sst receptors are known to form heterodimers with opioid receptors [86] which could contribute to the naloxone-dependent mechanism. By contrast, peripheral ghrelin signaling is not involved based on different kinetics with the rapid stimulation of food intake and delayed increase of plasma ghrelin levels induced by icv injection of ODT8-SST [59]. The increase of food intake after icv injection of ODT8-SST was associated with an elevation of energy expenditure [59, 87] and an increased respiratory quotient indicating preferential glucose oxidation and reduced lipid oxidation [59]. Similar alterations are also observed for other orexigenic peptides such as melanin-concentrating hormone [88].

Converging evidence supports the involvement of the sst2 in the central mediation of ODT8-SST orexigenic effects. First, the action of ODT8-SST on food intake was blocked by icv injection of a selective peptide sst2 antagonist in rats [59]. Second, the sst2 agonist, L-779 976 injected icv increases the 24-h meal frequency in rats [89]. Likewise, a newly developed selective peptide sst2 agonist injected icv increases food intake in rats [61] (Fig. 1). Similarly, the oligo-somatostatin agonist, octreotide displaying high affinity to the sst2 and only moderate affinity to sst3 and sst5 injected icv increases food intake in rats [76]. Third, neuroanatomical support is provided by the prominent expression of sst2 in rodent hypothalamic nuclei implicated in the regulation of food intake, namely the supraoptic nucleus, ventromedial and lateral hypothalamus, PVN and arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus [8, 67, 90–92]. Further supporting a physiological role of brain somatostatin signaling in the stimulation of feeding, we found that a selective peptide sst2 antagonist injected icv at the beginning of the dark phase, when rats normally eat, decreases nocturnal food intake [61]. Likewise, chronic third ventricular infusion of an anti-somatostatin antiserum over a period of two days decreases daily food intake in rats [76]. Lastly, the hypothalamic somatostatin content shows circadian variations with an increase at the beginning of the dark phase when rats show their maximal food intake and a decrease in the early light phase [93].

The finding of a stimulatory action of brain sst2 activation on food intake was recently extended to mice [94]. Similar to the observations in rats, the sst2 agonist injected icv increased food intake with a rapid onset and a long duration of action. In this study, we also analyzed the food intake microstructure which is of importance in order to unravel underlying mechanisms regulating the respective eating behavior [95]. This was achieved using a newly developed automated solid food intake monitoring device. The sst2 agonist injected icv in mice increased the number of meals, reduced inter-meal intervals and did not alter meal sizes compared to vehicle indicating that brain sst2 activation stimulates feeding via inhibition of satiety whereas satiation is not altered [94].

The orexigenic action of brain sst activation was also observed under conditions of stress. Restraint stress, a model of psychological stress, induces a reduction of food intake, an effect reversed by icv injection of somatostatin-14 or the oligo-somatostatin agonist, octreotide [96]. Similarly, abdominal surgery, a well established model to induce postoperative gastric ileus and a condition considered as physical stress robustly reduces re-feeding food intake in fasted rats. The icv injection of the pan-somatostatin agonist, ODT8-SST before surgery results in a near abolition of postsurgical hyporexia observed in the icv vehicle-treated animals undergoing surgery [62]. This effect is likely to be sst2 mediated since the icv injection of the selective sst2 agonist results in similar orexigenic effects on postoperative food intake [62]. Despite the fact that ODT8-SST restores the postoperatively reduced circulating levels of the orexigenic gastric hormone ghrelin, this effect is unlikely to underlie the observed increased food consumption as blockade of ghrelin signaling by a selective ghrelin receptor antagonist did not prevent ODT8-SST’s stimulatory effects on feeding [62].

4. EFFECTS ON THERMOGENESIS

Another brain action of somatostatin that was described early on, was the induction of hyperthermia, an effect where somatostatin-28 is more potent than somatostatin-14 [97]. Similarly, the pan-somatostatin agonist, ODT8-SST injected icv increases rectal temperature during the light phase [59]. Although hyperthermia is a well known response to cytokines such as interleukin-1 [98], this pathway is not involved in the signaling of ODT8-SST’s hyperthermic effect. The peripheral injection of cyclooxygenase inhibitor, indomethacin did not alter ODT8-SST’s action [59]. Moreover, food intake is inhibited by interleukin-1_ [98] and stimulated by icv ODT8-SST [59]. A recent study delineated that selective activation of brain sst2 also increases rectal temperature in rats, an effect that could be related to sst2 mediated increased activity as indicated by enhanced locomotor activity [61]. One of the brain structures involved in the mediation of hyperthermia may be the lateral parabrachial nucleus, where Fos expression is increased after icv injection of the sst2 agonist [16]. This is supported by a recent study showing that the physiologically important cold receptor, transient receptor potential melastatin-8 (TRPM8) signals to this nucleus as shown by suppressed Fos expression using a TRPM8 antagonist, N-(2-aminoethyl)-N-(4-(benzyloxy)-3-methoxybenzyl)thiophene-2-carboxamide hydrochloride under conditions of cold stress [99]. The centrally mediated thermogenic effect of somatostatin agonists is likely to represent a physiological action of brain somatostatin since hypothalamic somatostatin levels are correlated with ambient temperature [100] and rats develop hypothermia following brain injection of a somatostatin antagonist [101].

5. SUMMARY

Somatostatin receptors are widely expressed in the brain with specific patterns of distribution although notable regional overlap exists between the five receptor subtypes. Using specific peptide sst agonists and antagonists recent studies unraveled a physiological role of somatostatin as part of mechanisms contributing to the maintenance of normothermia, nocturnal feeding and locomotor activity. In addition, recent evidence established that somatostatin-28 and activation of sst receptors markedly influence several components of the stress response. While the GH inhibition induced by stress involves brain release of somatostatin, the endocrine (hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal-axis), autonomic and visceral (alterations of gut transit) responses to acute stressors are counteracted by pan-somatostatin agonists injection into the cerebrospinal fluid through selective activation of brain sst receptor subtypes. In particular, pharmacological evidence suggests that sst5 activation prevents the rise in epinephrine secretion and the inhibition of gastric emptying induced by different stressors while the sst1 agonist counteracts the stress-related activation of colonic motor function and sst2/5 blocked the stress-related stimulation of ACTH (Fig. 1). Therefore, the use of these pharmacological compounds not only allows us to delineate those pathways but may also be of relevance to therapeutically modulate body functions such as gastrointestinal motility e.g. after abdominal surgery to reduce the time of postoperative ileus. Future investigations combining the use of different selective agonists along with the development of highly selective co-agonists will be important to study the effects of heterodimerization, a phenomenon discussed to be relevant between sst receptors.

Acknowledgments

A.S. received Charité university funding and an equipment grant of the Sonnenfeld foundation. Y.T. is in receipt of thee VA Research Career Scientist Award, VA Merit Award and NIH R01 grants DK 33061 and DK 57238. JR is the Frederik Paulsen Chair in Neurosciences Professor.

Footnotes

Send Orders of Reprints at reprints@benthamscience.org

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Brazeau P, Vale W, Burgus R, et al. Hypothalamic polypeptide that inhibits the secretion of immunoreactive pituitary growth hormone. Science. 1973;179:77–9. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4068.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pradayrol L, Jornvall H, Mutt V, Ribet A. N-terminally extended somatostatin: the primary structure of somatostatin-28. FEBS Lett. 1980;109:55–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(80)81310-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olias G, Viollet C, Kusserow H, Epelbaum J, Meyerhof W. Regulation and function of somatostatin receptors. J Neurochem. 2004;89:1057–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown M, Taché Y. Hypothalamic peptides: central nervous system control of visceral functions. Fed Proc. 1981;40:2565–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finley JC, Maderdrut JL, Roger LJ, Petrusz P. The immunocyto-chemical localization of somatostatin-containing neurons in the rat central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1981;6:2173–92. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(81)90006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johansson O, Hokfelt T, Elde RP. Immunohistochemical distribution of somatostatin-like immunoreactivity in the central nervous system of the adult rat. Neuroscience. 1984;13:265–339. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moga MM, Gray TS. Evidence for corticotropin-releasing factor, neurotensin, and somatostatin in the neural pathway from the central nucleus of the amygdala to the parabrachial nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1985;241:275–84. doi: 10.1002/cne.902410304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fehlmann D, Langenegger D, Schuepbach E, Siehler S, Feuerbach D, Hoyer D. Distribution and characterisation of somatostatin receptor mRNA and binding sites in the brain and periphery. J Physiol Paris. 2000;94:265–81. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(00)00208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spary EJ, Maqbool A, Batten TF. Expression and localisation of somatostatin receptor subtypes sst1-sst5 in areas of the rat medulla oblongata involved in autonomic regulation. J Chem Neuroanat. 2008;35:49–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dragunow M, Faull R. The use of c-fos as a metabolic marker in neuronal pathway tracing. J Neurosci Methods. 1989;29:261–5. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(89)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sagar SM, Sharp FR, Curran T. Expression of c-fos protein in brain: metabolic mapping at the cellular level. Science. 1988;240:1328–31. doi: 10.1126/science.3131879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Senba E, Ueyama T. Stress-induced expression of immediate early genes in the brain and peripheral organs of the rat. Neurosci Res. 1997;29:183–207. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(97)00095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meddle SL, Bull PM, Leng G, Russell JA, Ludwig M. Somatostatin actions on rat supraoptic nucleus oxytocin and vasopressin neurones. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22:438–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamegai J, Minami S, Sugihara H, Wakabayashi I. Barrel rotation evoked by intracerebroventricular injection of somatostatin and arginine-vasopressin is accompanied by the induction of c-fos gene expression in the granular cells of rat cerebellum. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1993;18:115–20. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90179-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grace CR, Erchegyi J, Koerber SC, Reubi JC, Rivier J, Riek R. Novel sst2-selective somatostatin agonists. Three-dimensional consensus structure by NMR. J Med Chem. 2006;49:4487–96. doi: 10.1021/jm060363v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goebel M, Stengel A, Wang L, et al. Pattern of Fos expression in the brain induced by selective activation of somatostatin receptor 2 in rats. Brain Res. 2010;1351:150–64. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erchegyi J, Grace CR, Samant M, et al. Ring size of somatostatin analogues (ODT-8) modulates receptor selectivity and binding affinity. J Med Chem. 2008;51:2668–75. doi: 10.1021/jm701444y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mori K, Kim J, Sasaki K. Electrophysiological effect of ghrelin and somatostatin on rat hypothalamic arcuate neurons in vitro. Peptides. 2010;31:1139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chessell IP, Black MD, Feniuk W, Humphrey PP. Operational characteristics of somatostatin receptors mediating inhibitory actions on rat locus coeruleus neurones. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;117:1673–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connor M, Bagley EE, Mitchell VA, Ingram SL, Christie MJ, Humphrey PP, Vaughan CW. Cellular actions of somatostatin on rat periaqueductal grey neurons in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:1273–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bereiter DA. Morphine and somatostatin analogue reduce c-fos expression in trigeminal subnucleus caudalis produced by corneal stimulation in the rat. Neuroscience. 1997;77:863–74. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00541-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arancibia S, Rage F, Grauges P, Gomez F, Tapia-Arancibia L, Armario A. Rapid modifications of somatostatin neuron activity in the periventricular nucleus after acute stress. Exp Brain Res. 2000;134:261–7. doi: 10.1007/s002210000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Negro-Vilar A, Saavedra JM. Changes in brain somatostatin and vasopressin levels after stress in spontaneously hypertensive and Wistar-Kyoto rats. Brain Res Bull. 1980;5:353–8. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(80)80004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura H, Moroji T, Nagase H, Okazawa T, Okada A. Changes of cerebral vasoactive intestinal polypeptide- and somatostatin-like immunoreactivity induced by noise and whole-body vibration in the rat. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1994;68:62–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00599243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arancibia S, Epelbaum J, Boyer R, Assenmacher I. In vivo release of somatostatin from rat median eminence after local K+ infusion or delivery of nociceptive stress. Neurosci Lett. 1984;50:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(84)90469-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benyassi A, Gavalda A, Armario A, Arancibia S. Role of somatostatin in the acute immobilization stress-induced GH decrease in rat. Life Sci. 1993;52:361–70. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90149-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang K, Hamanaka K, Kitayama I, et al. Decreased expression of the mRNA for somatostatin in the periventricular nucleus of depression-model rats. Life Sci. 1999;65:PL87–94. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00326-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deutch AY, Bean AJ, Bissette G, Nemeroff CB, Robbins RJ, Roth RH. Stress-induced alterations in neurotensin, somatostatin and corticotropin-releasing factor in mesotelencephalic dopamine system regions. Brain Res. 1987;417:350–4. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90462-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Estupina C, Abarca J, Arancibia S, Belmar J. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor involvement in dexamethasone and stress-induced hypothalamic somatostatin release in rats. Neurosci Lett. 1996;219:203–6. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(96)13211-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arancibia S, Payet O, Givalois L, Tapia-Arancibia L. Acute stress and dexamethasone rapidly increase hippocampal somatostatin synthesis and release from the dentate gyrus hilus. Hippocampus. 2001;11:469–77. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franco-Bourland RE. Vasopressinergic, oxytocinergic, and somatostatinergic neuronal activity after adrenalectomy and immobilization stress. Neurochem Res. 1998;23:695–701. doi: 10.1023/a:1022447023840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen XQ, Du JZ. Hypoxia influences somatostatin release in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2000;284:151–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arancibia S, Estupina C, Tapia-Arancibia L. Rapid reduction in somatostatin mRNA expression by hypothalamic neurons induced by dexamethasone. Neuroreport. 2000;11:3163–7. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200009280-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nanda SA, Qi C, Roseboom PH, Kalin NH. Predator stress induces behavioral inhibition and amygdala somatostatin receptor 2 gene expression. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:639–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown MR, Rivier C, Vale W. Central nervous system regulation of adrenocorticotropin secretion: role of somatostatins. Endocrinology. 1984;114:1546–9. doi: 10.1210/endo-114-5-1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang XM, Tresham JJ, Coghlan JP, Scoggins BA. Intracerebroventricular infusion of a cyclic hexapeptide analogue of somatostatin inhibits hemorrhage-induced ACTH release. Neuroendocrinology. 1987;45:325–7. doi: 10.1159/000124747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viollet C, Vaillend C, Videau C, et al. Involvement of sst2 somatostatin receptor in locomotor, exploratory activity and emotional reactivity in mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3761–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katakami H, Arimura A, Frohman LA. Involvement of hypothalamic somatostatin in the suppression of growth hormone secretion by central corticotropin-releasing factor in conscious male rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1985;41:390–3. doi: 10.1159/000124207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rivier C, Vale W. Involvement of corticotropin-releasing factor and somatostatin in stress-induced inhibition of growth hormone secretion in the rat. Endocrinology. 1985;117:2478–82. doi: 10.1210/endo-117-6-2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aguila MC, Pickle RL, Yu WH, McCann SM. Roles of somatostatin and growth hormone-releasing factor in ether stress inhibition of growth hormone release. Neuroendocrinology. 1991;54:515–20. doi: 10.1159/000125946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fisher DA, Brown MR. Somatostatin analog: plasma catecholamine suppression mediated by the central nervous system. Endocrinology. 1980;107:714–8. doi: 10.1210/endo-107-3-714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Feuerbach D, Fehlmann D, Nunn C, Siehler S, Langenegger D, Bouhelal R, Seuwen K, Hoyer D. Cloning, expression and pharmacological characterisation of the mouse somatostatin sst(5) receptor. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:1451–62. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown MR. Central nervous system sites of action of bombesin and somatostatin to influence plasma epinephrine levels. Brain Res. 1983;276:253–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90732-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carver-Moore K, Gray TS, Brown MR. Central nervous system site of action of bombesin to elevate plasma concentrations of catecholamines. Brain Res. 1991;541:225–31. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91022-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miles PD, Yamatani K, Brown MR, Lickley HL, Vranic M. Intracerebroventricular administration of somatostatin octapeptide counteracts the hormonal and metabolic responses to stress in normal and diabetic dogs. Metabolism. 1994;43:1134–43. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(94)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown M, Fisher L, Mason RT, Rivier J, Vale W. Neurobiological actions of cysteamine. Fed Proc. 1985;44:2556–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown MR, Fisher LA. Central nervous system actions of somatostatin-related peptides. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1985;188:217–28. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-7886-4_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown MR, Fisher LA, Sawchenko PE, Swanson LW, Vale WW. Biological effects of cysteamine: relationship to somatostatin depletion. Regul Pept. 1983;5:163–79. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(83)90124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Somiya H, Tonoue T. Neuropeptides as central integrators of autonomic nerve activity: effects of TRH, SRIF, VIP and bombesin on gastric and adrenal nerves. Regul Pept. 1984;9:47–52. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(84)90006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strack AM, Sawyer WB, Platt KB, Loewy AD. CNS cell groups regulating the sympathetic outflow to adrenal gland as revealed by transneuronal cell body labeling with pseudorabies virus. Brain Res. 1989;491:274–96. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Debas HT, Carvajal SH. Vagal regulation of acid secretion and gastrin release. Yale J Biol Med. 1994;67:145–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taché Y, Rivier J, Vale W, Brown M. Is somatostatin or a somatostatin-like peptide involved in central nervous system control of gastric secretion? Regul Pept. 1981;1:307–15. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(81)90054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoneda M, Raybould H, Taché Y. Central action of somatostatin analog, SMS 201-995, to stimulate gastric acid secretion in rats. Peptides. 1991;12:401–6. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(91)90076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yoneda M, Taché Y. SMS 201-995-induced stimulation of gastric acid secretion via the dorsal vagal complex and inhibition via the hypothalamus in anaesthetized rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;116:2303–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martinez V, Coy DH, Taché Y. Influence of intracisternal injection of somatostatin analog receptor subtypes 2, 3 and 5 on gastric acid secretion in conscious rats. Neurosci Lett. 1995;186:79–82. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martinez V, Coy DH, Lloyd KC, Taché Y. Intracerebroventricular injection of somatostatin sst5 receptor agonist inhibits gastric acid secretion in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;296:153–60. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00690-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martinez V, Rivier J, Coy D, Taché Y. Intracisternal injection of somatostatin receptor 5-preferring agonists induces a vagal cholinergic stimulation of gastric emptying in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:1099–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thoss VS, Perez J, Duc D, Hoyer D. Embryonic and postnatal mRNA distribution of five somatostatin receptor subtypes in the rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1673–88. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00135-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stengel A, Coskun T, Goebel M, et al. Central injection of the stable somatostatin analog ODT8-SST induces a somatostatin2 receptor-mediated orexigenic effect: role of neuropeptide Y and opioid signaling pathways in rats. Endocrinology. 2010;151:4224–35. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stengel A, Goebel-Stengel M, Wang L, Larauche M, Rivier J, Taché Y. Central somatostatin receptor 1 activation reverses acute stress-related alterations of gastric and colonic motor function in mice. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:e223–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01706.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stengel A, Goebel M, Wang L, et al. Selective central activation of somatostatin2 receptor increases food intake, grooming behavior and rectal temperature in rats. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2010;61:399–407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stengel A, Goebel-Stengel M, Wang L, et al. Central administration of pan-somatostatin agonist ODT8-SST prevents abdominal surgery-induced inhibition of circulating ghrelin, food intake and gastric emptying in rats. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:e294–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rocheville M, Lange DC, Kumar U, Sasi R, Patel RC, Patel YC. Subtypes of the somatostatin receptor assemble as functional homo- and heterodimers. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7862–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mönnikes H, Raybould HE, Schmidt B, Taché Y. CRF in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus stimulates colonic motor activity in fasted rats. Peptides. 1993;14:743–7. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(93)90107-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mönnikes H, Schmidt BG, Tebbe J, Bauer C, Taché Y. Microinfusion of corticotropin releasing factor into the locus coeruleus/subcoeruleus nuclei stimulates colonic motor function in rats. Brain Res. 1994;644:101–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90352-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tebbe JJ, Pasat IR, Mönnikes H, Ritter M, Kobelt P, Schafer MK. Excitatory stimulation of neurons in the arcuate nucleus initiates central CRF-dependent stimulation of colonic propulsion in rats. Brain Res. 2005;1036:130–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schulz S, Handel M, Schreff M, Schmidt H, Hollt V. Localization of five somatostatin receptors in the rat central nervous system using subtype-specific antibodies. J Physiol Paris. 2000;94:259–64. doi: 10.1016/s0928-4257(00)00212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Martinez V, Wang L, Rivier J, Grigoriadis D, Taché Y. Central CRF, urocortins and stress increase colonic transit via CRF1 receptors while activation of CRF2 receptors delays gastric transit in mice. J Physiol. 2004;556:221–34. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.059659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang L, Martinez V, Kimura H, Taché Y. 5-Hydroxytryptophan activates colonic myenteric neurons and propulsive motor function through 5-HT4 receptors in conscious mice. Am J Physiol Gastro-intest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G419–28. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00289.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rezek M, Havlicek V, Leybin L, et al. Neostriatal administration of somatostatin: differential effect of small and large doses on behavior and motor control. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1977;55:234–42. doi: 10.1139/y77-034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ishikawa Y, Shimatsu A, Murakami Y, Imura H. Barrel rotation in rats induced by SMS 201-995: suppression by ceruletide. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1990;37:523–6. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(90)90022-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Allen JP, Hathway GJ, Clarke NJ, et al. Somatostatin receptor 2 knockout/lacZ knockin mice show impaired motor coordination and reveal sites of somatostatin action within the striatum. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1881–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hamada T, Shibata S, Tsuneyoshi A, Tominaga K, Watanabe S. Effect of somatostatin on circadian rhythms of firing and 2-deoxyglucose uptake in rat suprachiasmatic slices. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:R1199–204. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.5.R1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rezek M, Havlicek V, Hughes KR, Friesen H. Central site of action of somatostatin (SRIF): role of hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 1976;15:499–504. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(76)90062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lin MT, Chen JJ, Ho LT. Hypothalamic involvement in the hyperglycemia and satiety actions of somatostatin in rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1987;45:62–7. doi: 10.1159/000124704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Danguir J. Food intake in rats is increased by intracerebroventricular infusion of the somatostatin analogue SMS 201-995 and is decreased by somatostatin antiserum. Peptides. 1988;9:211–3. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(88)90030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Feifel D, Vaccarino FJ. Central somatostatin: a re-examination of its effects on feeding. Brain Res. 1990;535:189–94. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91600-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Feifel D, Vaccarino FJ, Rivier J, Vale WW. Evidence for a common neural mechanism mediating growth hormone-releasing factor-induced and somatostatin-induced feeding. Neuroendocrinology. 1993;57:299–305. doi: 10.1159/000126372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tachibana T, Cline MA, Sugahara K, Ueda H, Hiramatsu K. Central administration of somatostatin stimulates feeding behavior in chicks. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2009;161:354–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vijayan E, McCann SM. Suppression of feeding and drinking activity in rats following intraventricular injection of thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH) Endocrinology. 1977;100:1727–30. doi: 10.1210/endo-100-6-1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aponte G, Leung P, Gross D, Yamada T. Effects of somatostatin on food intake in rats. Life Sci. 1984;35:741–6. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90342-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tannenbaum GS, Patel YC. On the fate of centrally administered somatostatin in the rat: massive hypersomatostatinemia resulting from leakage into the peripheral circulation has effects on growth hormone secretion and glucoregulation. Endocrinology. 1986;118:2137–43. doi: 10.1210/endo-118-5-2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.de la Cour CD, Norlen P, Hakanson R. Secretion of ghrelin from rat stomach ghrelin cells in response to local microinfusion of candidate messenger compounds: a microdialysis study. Regul Pept. 2007;143:118–26. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Silva AP, Bethmann K, Raulf F, Schmid HA. Regulation of ghrelin secretion by somatostatin analogs in rats. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;152:887–94. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.01914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schick RR, Schusdziarra V, Nussbaumer C, Classen M. Neuropeptide Y and food intake in fasted rats: effect of naloxone and site of action. Brain Res. 1991;552:232–9. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90087-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Duran-Prado M, Malagon MM, Gracia-Navarro F, Castano JP. Dimerization of G protein-coupled receptors: new avenues for somatostatin receptor signalling, control and functioning. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;286:63–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Brown MR. Bombesin and somatostatin related peptides: effects on oxygen consumption. Brain Res. 1982;242:243–6. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90306-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guesdon B, Paradis E, Samson P, Richard D. Effects of intracerebroventricular and intra-accumbens melanin-concentrating hormone agonism on food intake and energy expenditure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R469–75. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90556.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stepanyan Z, Kocharyan A, Behrens M, Koebnick C, Pyrski M, Meyerhof W. Somatostatin, a negative-regulator of central leptin action in the rat hypothalamus. J Neurochem. 2007;100:468–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Moller LN, Stidsen CE, Hartmann B, Holst JJ. Somatostatin receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1616:1–84. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stepanyan Z, Kocharyan A, Pyrski M, et al. Leptin-target neurones of the rat hypothalamus express somatostatin receptors. J Neuroendocrinol. 2003;15:822–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2003.01077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Csaba Z, Simon A, Helboe L, Epelbaum J, Dournaud P. Targeting sst2A receptor-expressing cells in the rat hypothalamus through in vivo agonist stimulation: neuroanatomical evidence for a major role of this subtype in mediating somatostatin functions. Endocrinology. 2003;144:1564–73. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-221090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gardi J, Obal F, Jr, Fang J, Zhang J, Krueger JM. Diurnal variations and sleep deprivation-induced changes in rat hypothalamic GHRH and somatostatin contents. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:R1339–44. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.5.R1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Stengel A, Goebel M, Wang L, et al. Activation of brain somatostatin(2) receptors stimulates feeding in mice: Analysis of food intake microstructure. Physiol Behav. 2010;101:614–22. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Geary N. A new way of looking at eating. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R1444–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00066.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shibasaki T, Yamauchi N, Kato Y, et al. Involvement of corticotropin-releasing factor in restraint stress-induced anorexia and reversion of the anorexia by somatostatin in the rat. Life Sci. 1988;43:1103–10. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(88)90468-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brown M, Ling N, Rivier J. Somatostatin-28, somatostatin-14 and somatostatin analogs: effects on thermoregulation. Brain Res. 1981;214:127–35. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90443-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lawrence CB, Rothwell NJ. Anorexic but not pyrogenic actions of interleukin-1 are modulated by central melanocortin-3/4 receptors in the rat. J Neuroendocrinol. 2001;13:490–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2001.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Almeida MC, Hew-Butler T, Soriano RN, et al. Pharmacological blockade of the cold receptor TRPM8 attenuates autonomic and behavioral cold defenses and decreases deep body temperature. J Neurosci. 2012;32:2086–99. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5606-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lin MT, Uang WN, Ho LT, Chuang J, Fan LJ. Somatostatin: a hypothalamic transmitter for thermoregulation in rats. Pflugers Arch. 1989;413:528–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00594185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ao Y, Go VL, Toy N, et al. Brainstem thyrotropin-releasing hormone regulates food intake through vagal-dependent cholinergic stimulation of ghrelin secretion. Endocrinology. 2006;147:6004–10. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]