A long observed attribute of tumor cells, which sets them apart from most normal cells, is a high uptake of glucose. The glucose subsequently enters the glycolytic pathway and is converted to lactate, even in the presence of oxygen. This phenomenon, known as aerobic glycolysis1, is thought to allow growing cells to use glycolytic intermediates for biosynthetic processes critical for proliferation. The glycolytic phenotype of cells hinges on the fate of pyruvate, the intermediate converted to lactate in cancer cells, but enters the mitochondria to fuel oxidative phosphorylation in resting cells.

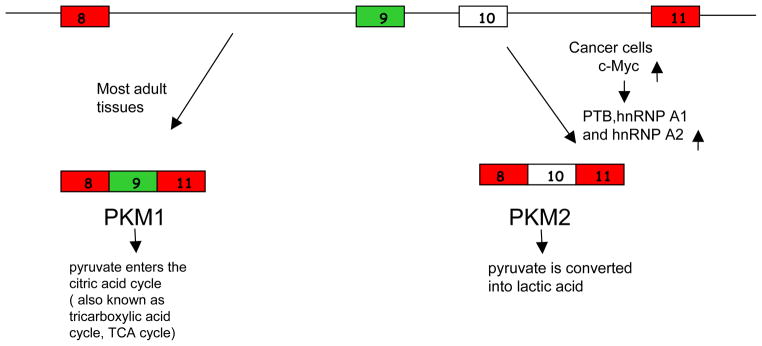

The enzyme that produces pyruvate, pyruvate kinase, has been implicated as a critical determinant of metabolic phenotype. In mammals, most tissues express the pyruvate kinase M (PKM) gene. PKM can produce two different isoforms by mutually exclusive inclusion of exon 9 or 10 during splicing of the mRNA precursor. The form expressed in most adult tissues, PKM1, contains exon 9, while the form expressed in growing (e.g., embryonic) cells, PKM2, contains exon 10. In tumor cells, or other cells induced to proliferate, reversion to PKM2 occurs, and is near universal and complete. Cantley and colleagues showed that when tumors are forced to express the PKM1 isoform rather than PKM2, aerobic glycolysis is reduced, oxidative phosphorylation is increased, and tumor growth is impaired, indicating that PKM isoform expression is a key determinant of how cells use glucose, and for proliferation of tumor cells2.

Given their critical and opposing roles in determining the cell’s glycolytic phenotype, the regulation of switching between PKM1 and PKM2 splicing is of great interest. To investigate this, David et al.3 set out to identify potential regulatory proteins. Alternative splicing is regulated by proteins that bind to specific RNA sequences, including members of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) protein family, such as hnRNP A1, hnRNP A2 and PTB (also known as hnRNP I)4. Using UV crosslinking and RNA affinity chromatography, it was observed that these three proteins bind to intronic sequences flanking PKM exon 9 but not exon 10. Furthermore, the binding sequences are similar to their known consensus binding sites5, 6 and are conserved between mouse and human. To examine whether hnRNP A1, hnRNP A2 and PTB are functionally involved in PKM alternative splicing regulation, the three proteins were depleted by siRNAs in HeLa cells and other cancer cell lines. PKM1 mRNA levels were significantly increased and PKM2 mRNA levels were concomitantly decreased, indicating that hnRNP A1, hnRNP A2 and PTB expression levels are the critical determinant of the expression of PKM2 isoform in transformed cells, likely by repressing exon 9 inclusion.

The mouse myoblast cell line C2C12 can be induced to differentiate into myotubes, a process that brings about switching from PKM2 to PKM1 expression, and David et al. observed a decrease in PTB and hnRNP A1 protein levels3. This result further supports the model that high expression levels of PTB and hnRNP A1 repress the inclusion of exon 9 to maintain the expression of PKM2 in proliferating cells. Because of the importance of PKM2 in cancer cell growth2, different classes of human glioma tumor samples were examined for a correlation between PTB, hnRNP A1 and hnRNP A2 expression levels and PKM splicing. Consistently, all tumor samples with high PKM2 expression, most notably the aggressive glioblastoma multiforme, were found to have elevated levels of PTB, hnRNP A1 and hnRNP A2.

Given the key role of PTB, hnRNP A1 and hnRNP A2 in promoting PKM2, and the tight coupling of PKM2 splicing and proliferation, David et al. next asked whether the expression of the three hnRNP proteins is under control of a proliferation-associated transcription factor. c-Myc has been shown to bind to PTB, hnRNP A1 and hnRNP A2 promoters and to upregulate their expression levels7–9. Significantly, c-Myc expression was found to correlate with PTB, hnRNP A1 and hnRNP A2 expression almost perfectly in human glioma tumor samples, and c-Myc directly stimulates transcription of hnRNP A13. Most importantly, siRNA-mediated reductions in c-Myc levels in NIH3T3 cells not only led to decreased mRNA and protein levels of PTB, hnRNP A1 and hnRNP A2, but also switched PKM splicing from PKM2 to PKM13. These results demonstrated a role of c-Myc in directly activating transcription of PTB, hnRNP A1 and hnRNP A2 genes and ensuring high levels of PKM2 in proliferating cells (Figure 1). As c-Myc is upregulated in numerous cancers10, this provides a satisfying mechanism for how this important aspect of cell growth control is deregulated in cancer.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of PKM splicing pattern in different cell types. Exon 9 and exon 10 of PKM pre-mRNA are mutually exclusive exons that are alternatively spliced to produce two PKM isoforms. PKM1, which contains exon 9, is expressed in most adult tissues, and the pyruvate produced by PKM1 goes into TCA cycle for oxidative phosphorylation. PKM2, which contains exon 10, is expressed in embryonic cells and cancer cells. The pyruvate produced by the less active PKM2 is preferentially converted into lactic acid.

PTB, hnRNP A1 and hnRNP A2 have been observed to be upregulated in a wide variety of cancers11–13. Repression of PKM exon 9 inclusion and therefore the dominance of the PKM2 isoform in proliferating cells is at least one important functional consequence of this phenomenon. The results of David et al. indicate that overexpression of some combination of these three proteins in cancer is, like PKM2 expression, likely to be a general phenomenon. The fact that c-Myc depletion did not bring about PKM1 to PKM2 switching in all cell lines tested, including Hela cells3 suggests that additional transcription factors are capable of promoting PTB, hnRNP A1 and hnRNP A2 upregulation in some tumor cells. ChIP- seq data indicate that E2F family transcription factors as well as AP-1 proteins such as c-Fos bind to the promoters of the hnRNP A1, A2 and PTB genes, suggesting that multiple proliferation-associated pathways exist that bring about high expression of these proteins in a variety of cancers14. The intimate link between PKM alternative splicing, cell proliferation, and the RNA-binding proteins identified by David et al., casts the familiar hnRNP A1, A2 and PTB proteins in a new role: proliferation-associated splicing factors.

References

- 1.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–14. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christofk HR, Vander Heiden MG, Harris MH, Ramanathan A, Gerszten RE, Wei R, Fleming MD, Schreiber SL, Cantley LC. The M2 splice isoform of pyruvate kinase is important for cancer metabolism and tumour growth. Nature. 2008;452:230–3. doi: 10.1038/nature06734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.David CJ, Chen M, Assanah M, Canoll P, Manley JL. HnRNP proteins controlled by c-Myc deregulate pyruvate kinase mRNA splicing in cancer. Nature. 463:364–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen M, Manley JL. Mechanisms of alternative splicing regulation: insights from molecular and genomics approaches. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:741–54. doi: 10.1038/nrm2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burd CG, Dreyfuss G. RNA binding specificity of hnRNP A1: significance of hnRNP A1 high-affinity binding sites in pre-mRNA splicing. EMBO J. 1994;13:1197–204. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06369.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spellman R, Rideau A, Matlin A, Gooding C, Robinson F, McGlincy N, Grellscheid SN, Southby J, Wollerton M, Smith CW. Regulation of alternative splicing by PTB and associated factors. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:457–60. doi: 10.1042/BST0330457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen X, Xu H, Yuan P, Fang F, Huss M, Vega VB, Wong E, Orlov YL, Zhang W, Jiang J, Loh YH, Yeo HC, Yeo ZX, Narang V, Govindarajan KR, Leong B, Shahab A, Ruan Y, Bourque G, Sung WK, Clarke ND, Wei CL, Ng HH. Integration of external signaling pathways with the core transcriptional network in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:1106–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiio Y, Donohoe S, Yi EC, Goodlett DR, Aebersold R, Eisenman RN. Quantitative proteomic analysis of Myc oncoprotein function. EMBO J. 2002;21:5088–96. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlosser I, Holzel M, Hoffmann R, Burtscher H, Kohlhuber F, Schuhmacher M, Chapman R, Weidle UH, Eick D. Dissection of transcriptional programmes in response to serum and c-Myc in a human B-cell line. Oncogene. 2005;24:520–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eilers M, Eisenman RN. Myc’s broad reach. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2755–66. doi: 10.1101/gad.1712408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He X, Pool M, Darcy KM, Lim SB, Auersperg N, Coon JS, Beck WT. Knockdown of polypyrimidine tract-binding protein suppresses ovarian tumor cell growth and invasiveness in vitro. Oncogene. 2007;26:4961–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zerbe LK, Pino I, Pio R, Cosper PF, Dwyer-Nield LD, Meyer AM, Port JD, Montuenga LM, Malkinson AM. Relative amounts of antagonistic splicing factors, hnRNP A1 and ASF/SF2, change during neoplastic lung growth: implications for pre-mRNA processing. Mol Carcinog. 2004;41:187–96. doi: 10.1002/mc.20053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanamura A, Caceres JF, Mayeda A, Franza BR, Jr, Krainer AR. Regulated tissue-specific expression of antagonistic pre-mRNA splicing factors. RNA. 1998;4:430–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birney E, et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]