Abstract

The advent of multimodal neuroimaging has provided acute stroke care providers with an armamentarium of sophisticated imaging options to utilize for guidance in clinical decision-making and management of acute ischemic stroke patients. Here, we propose a framework and potential algorithm-based methodology for imaging modality selection and utilization for the purpose of achieving optimal stroke clinical care. We first review imaging options that may best inform decision-making regarding revascularization eligibility, with a focus on the imaging modalities that best identify critical inclusion and exclusion criteria. Next, we review imaging methods that may guide the successful achievement of revascularization once it has been deemed desirable and feasible. Further, we review imaging modalities that may best assist in both the non-interventional care of acute stroke as well as the identification of stroke-mimics. Finally, we review imaging techniques under current investigation that show promise to improve future acute stroke management.

Keywords: Imaging, revascularization, perfusion, stroke, collaterals

Introduction

The clinical spectrum and management of stroke may vary widely based upon multiple lesion-specific factors. Consequently, advanced stroke imaging has become an integral tool in acute stroke diagnosis and care.

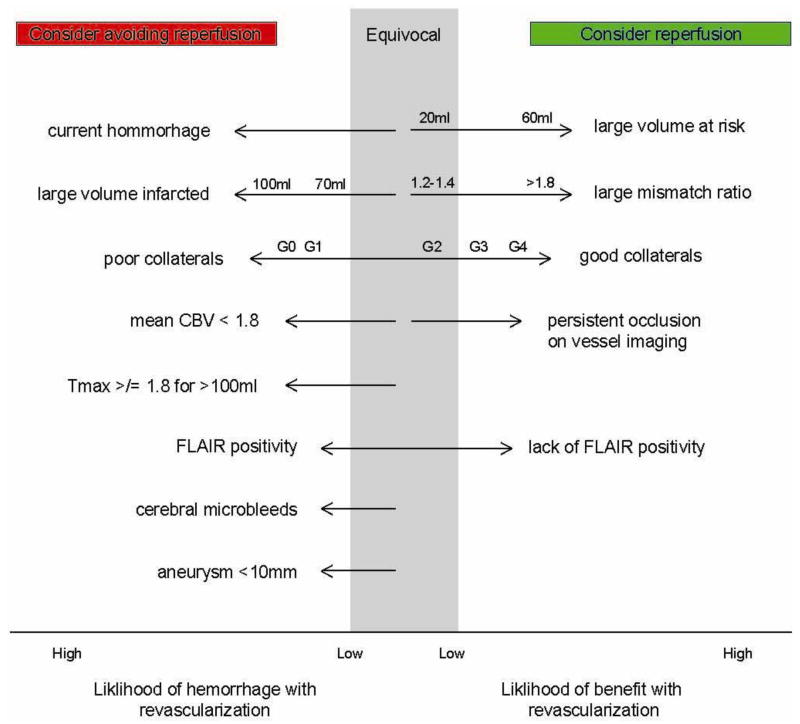

Reopening occluded vessels is a mainstay of interventional strategies in acute ischemic stroke; therefore, eligibility determination for such therapies is the first priority that must be addressed in patients suspected of having acute ischemic stroke. The only FDA-approved therapy for reopening vessels in acute ischemic stroke is intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA). Other interventions are endovascular and include delivery of intra-arterial (IA) thrombolysis and mechanical thrombectomy. Each of these interventions requires the use of neuroimaging to assess that certain inclusion and exclusion criteria are met for each therapy’s safe and efficacious use. Neuroimaging historically has been and remains most commonly relied upon to exclude acute cerebral hemorrhage for determination of tPA eligibility. However, neuroimaging has also become relied upon to determine eligibility for and likely feasibility of endovascular treatments. This is chiefly through identifying at-risk, but viable and ischemic tissue, as well as the collateral status of the involved cerebrovascular territory (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The imaging variables on the left of the diagram represent increased likelihood of reperfusion hemorrhage and therefore should prompt one to consider withholding of reperfusion therapy. The degree to which the presence of each variable should sway the clinician against reperfusion is reflected by the length of each arrow. The variables listed on the right of the diagram suggest a patient is likely to benefit from reperfusion. Again the length of the arrow is proportional to how heavily each variable should be weighted in clinical decision-making. Volumes are measured in milliliters (ml). Mismatch ratio is expressed as “at risk tissue/infarcted tissue”. The collateral grades are as follows: Grade 0 (no visible collateral to the ischemic site), Grade 1 (slow collaterals to the periphery of the ischemic site with persistence of some of the defect), Grade 2 (rapid collaterals to the periphery of ischemic site with persistence of some of the defect and to only a portion of the ischemic territory), Grade 3 (collaterals with slow but complete angiographic blood flow of the ischemic bed by the late venous phase), Grade 4 (complete and rapid collateral blood flow to the vascular bed in the entire ischemic territory by retrograde perfusion) (Higashida, Furlan et al. 2003).

In addition to its utility in acute therapies, neuroimaging may also be helpful in guiding a variety of other acute stroke management strategies that span from augmenting cerebral perfusion towards salvage of at-risk tissue to ameliorating the effects of mass effect from acute intracranial hemorrhage and edema. Each of these treatments benefits from specific neuroimaging techniques that afford proper diagnostic assessment to optimize treatment planning.

The principal aim of this review is to provide an empirically-based, data-driven overview of advanced imaging techniques that are the most valuable for clinical decision-making in acute stroke. We provide a framework for appropriate consideration of the extensive information provided by multimodal CT and MR modalities in acute stroke patients. Within the context of a pragmatic, time- and cost-sensitive protocol, we attempt to define a set of the most useful questions that a stroke clinician may ask of neuroimaging to answer.

I. Use of imaging to determine revascularization treatment eligibility

Intracranial hemorrhage assessment

The primary contraindication to IV or IA thrombolysis in treatment of acute ischemic stroke is the presence of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) at the time of presentation; as the most likely mimic of acute ischemic stroke, ICH’s timely and definitive detection is therefore critical. Non-contrast computed tomography (NCT) is the most widely available and used image technique for detecting ICH. For MRI, Gradient echo (GRE) imaging is as good as or better than NCT for assessing ICH [1]. While clinical symptoms of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) are typically different than those with ischemic stroke, the two may overlap in symptomatology. Furthermore, the two can be seen together when vasospasm, a frequent complication of SAH, leads to acute ischemia. GRE is less sensitive than NCT for detection of subarachnoid blood; however, MRI FLAIR appears to be comparable or even superior [2]. Lumbar puncture is still the standard for recognizing CT- and MRI-negative SAH [3].

Reperfusion hemorrhage assessment

When considering IV or endovascular treatments to re-establish perfusion, risk and benefit are inherently related. Reperfusion has the potential to either save tissue or cause hemorrhage (Figure 1). Several neuroimaging methods have been utilized to predict which patients may develop reperfusion-related hemorrhage after successful revascularization. Infarct size is the most established risk factor for reperfusion-related hemorrhage. Evidence of infarct volume of greater than 70–100cc on diffusion-weighted MRI (DWI), perfusion CT (CTP), or NCT should give pause as patients with such strokes are more likely to sustain reperfusion-related hemorrhage and poor outcome [4], [5].

Furthermore, ischemic infarcts that appear >1/3 of the MCA territory also should give pause to thrombolytic treatment based upon the post-hoc observation in the ECASS trial that these patients were most likely to suffer from hemorrhagic complications [6]. For this reason, NINDS and PROACT II excluded strokes with volume greater than 1/3 MCA in their studies. A standardized way to discern infarct size on CT is the Alberta Stroke Program Early CT (ASPECT) score. It has been shown that an ASPECT score <7 is a reliable way to discern whether >1/3 of MCA is involved [7]. Having an ASPECT of <7 also predicts higher rates of reperfusion related hemorrhage with IA or IV thrombolytics [8].

Perfusion imaging can also be useful in assessment of reperfusion-related hemorrhagic risk. For a given large volume of infarct (100ml), perfusion weighted MRI and CT may suggest high risk of hemorrhagic complication if Tmax is delayed at least 8 seconds or if the mean CBV is less than 1.8 ml/100g, respectively. [9], [10]. Signs that indicate blood brain barrier permeability may also indicate a higher risk of reperfusion-related hemorrhage [11], [12], [13].

GRE frequently identifies cerebral microbleeds that may reflect an underlying vasculopathy and possible predisposition to hemorrhagic transformation [14], [15]. This frequent incidental finding on MRI begs the question of whether these microbleeds affect the risk of reperfusion-related hemorrhage. The BRASIL study, the largest of its kind, evaluated the association between microbleeds on GRE and symptomatic ICH in thrombolytic-treated stroke. 15% of BRASIL patients had microbleeds emphasizing how common this incidental finding may be. Symptomatic ICH was seen in 5.8% of patients with microbleeds and 2.7% of those without: a small and not statistically significant difference, suggesting no definite increased risk of tPA-related hemorrhage in the presence of the former [16]. Although presence of microbleeds does not clearly convey increased risk, some have argued that specific location of cerebral microbleeds in fact does [17]. In total, however, current evidence does not support <5 cerebral microbleeds as a contraindication to reperfusion therapy. It is noteworthy that, in the event that GRE sequences are unavailable or unreadable, B0 images on DWI can rule out intracerebral hemorrhage but probably not microbleeds [18], [19].

While presence of an unruptured cerebral aneurysm is considered a relative contraindication to IV tPA in treatment of acute ischemic stroke, there is no definitive evidence to suggest that tPA increases risk of aneurysmal rupture. Moreover, there is even data to suggest that its use is relatively safe in patients with aneurysms <10mm in diameter [20].

Revascularization treatment eligibility for strokes of unknown duration

Seminal animal studies have shown that restricted diffusion of water from cytotoxic edema occurs within minutes of stroke onset while a net increase in water detected as increased T2 FLAIR signal occurs on the order of 1–4 hours [21], [22], [23]. Consequently, DWI hyperintensity and concurrent FLAIR isointensity are seen in acute ischemic stroke of typically <4.5 hours duration. Therefore, in cases of unknown symptom duration such as in “wake-up strokes,” DWI and FLAIR may be considered together as a potential surrogate for time for determination of revascularization eligibility. Thomalla et al 2011 studied 543 patients with acute stroke and known symptom onset. In this patient population, DWI-FLAIR mismatch identified patients within 4.5 hours of symptom onset with a PPV of 83% and a NPV of 54%. This suggests that FLAIR negativity should be weighted somewhat heavily in favor of giving IV lytics while FLAIR positivity should be weighted less heavily in favor of withholding IV lytics [24]. There was a great deal of variance in time to FLAIR positivity in Thomalla et al’s sample, which raised an interesting point. Some patients progress to FLAIR positivity rapidly while in others the cellular events resulting in endothelial breakdown, vasogenic edema and FLAIR hyperintensity take longer. This gives rise to the notion of the “tissue clock” which would differ significantly from the time clock. According to the tissue clock hypothesis, patients presenting beyond an approved time for reperfusion therapy could still be eligible because the cellular events underlying the risk of late reperfusion will have not yet occurred. More work and additional imaging metrics are likely needed to constitute a tissue clock reliable enough to guide therapy. Neuroprotective strategies such as intravenous magnesium designed to slow these intracellular events can now be delivered in the pre-hospital setting. Therefore the establishment of a neuroimaging tissue clock has the potential to make more patients eligible for revascularizing therapies [25].

Exclusion of stroke mimics

Ischemic stroke is a common etiology for sudden-onset neurological symptoms; however, other causes of neurological dysfunction may also present similarly. Therefore, imaging may help corroborate ischemia and exclude its mimics. Restricted or abnormal diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) on MRI and reduced cerebral blood volume (CBV) on CTP both provide comparably sensitive indices for acute ischemia [26]. However, abnormalities of diffusion and perfusion can be seen in stroke mimics as well. In seizure, for example diffusion and perfusion abnormalities can occur that may be distinct from those in ischemic stroke. On perfusion imaging signs of hyperemia may be seen such as decreased mean transit time (MTT), increased CBV and cerebral blood flow (CBF) may be seen particularly if imaging is performed during the seizure. On the other hand, post-ictally, seizure can have a similar perfusion signatures to those of acute ischemic stroke with increased MTT, decreased CBV and CBF [27]. Areas of restricted diffusion or perfusion abnormalities in interconnected cortical, hippocampal, and thalamic regions, that do not respect vascular territories should prompt consideration of seizure rather than stroke [28]. Like seizure, posterior reversible leukoencephalopathy (PRES) may also mimic ischemic stroke but show hyperemia on perfusion imaging [29]. Venous infarcts are often associated with parenchymal hemorrhage and distinct patterns of restricted diffusion on MRI, hypodensity on CT, or hypoperfusion on perfusion imaging. These findings should prompt further examination of possible sinus venous thrombosis, cortical vein thrombosis, or malignant dural arteriorvenous fistula [30], [27]. Mass lesions should also be considered as potential stroke mimics but it is beyond the scope of this review to compare the findings on CT, MRI, and perfusion imaging in the protean neoplasms that can affect the brain.

II. Imaging findings that predict likely need for and response to reperfusion therapy

Identification of the patient with mild symptoms who may worsen clinically

There are a significant number of patients that are eligible for IV and endovascular reperfusion therapies, but who do not receive them. The most common reason for withholding IV tPA among patients arriving within 3 hours is mild neurologic impairment and/or rapidly improving symptoms [31], [32]. While the majority of patients with minor strokes do well, a significant fraction of them unfortunately clinically worsen after the decision to withhold revascularization is made. In one large retrospective study of ischemic stroke patients, 27% received IV TPA therapy but a further 31% were excluded because their symptoms were either considered too mild or were rapidly improving. Subsequently, a third of these untreated patients became functionally dependent or died [33]. In another analysis of patients eligible for either IV or IA therapy who went untreated because of mild or improving symptoms, 10% had infarct expansion and neurologic deterioration [34]. Thus, additional studies have been proposed to help clarify which patients with minor ischemic stroke most likely will clinically worsen and, as a result, may benefit most from reperfusion therapy. While persistent large vessel occlusion likely increases the risk of clinical deterioration and infarct expansion [34], utilization of neuroimaging to identify salvageable tissue and characterize collateral flow has seemingly great potential to aid in this determination of which mild strokes may best benefit from reperfusion treatment.

Quantification of at risk but viable brain tissue

The goal of reperfusion therapy in acute stroke is to save brain tissue that is ischemic but not yet infarcted. Therefore the central task of perfusion imaging is to discriminate infarcted core from the ischemic penumbra.

On MRI, infarct core is best described by areas of restricted diffusion. However, DWI can actually be somewhat dynamic, and other MR variables may also be considered to represent infarct core [35], [36]. The characterization of brain that will go on to infarct is more elusive and several perfusion parameters have been argued to correlate well with brain at risk of infarction. One often used parameter to estimate regions of brain at risk on perfusion MRI (PWI) is Tmax greater than 6 seconds [37], [38]. One reason for the elusive nature of describing at-risk brain tissue with perfusion imaging is that imaging represents a single snapshot of perfusion status: the true perfusion status of tissue is likely a much more dynamic process reflecting collateral dynamics, volume status, and blood pressure over the course of hours to days. While diffusion sequences on MRI are relatively easy to read and interpret, perfusion images require time intensive post-processing to generate the qualitative relative CBV and MTT measures. Therefore it is worth noting that percentage of baseline at peak (PBP) which is similar to but less sensitive than CBV requires less post-processing to generate and is more rapidly available for review [39]. NCT is not sufficiently sensitive to distinguish areas of infarction. However, infarct core is well represented by areas of decreased absolute CBV below 2ml/100g on CTP. As is the case for perfusion weighted MRI, at risk ischemic tissue is likely to be harder to define. However it is reasonable to use a relative MTT of greater than 145% of the contralateral hemisphere [40]. MTT thresholds may help to distinguish between areas of benign hypoperfusion and at-risk brain [41].

Acute stroke patients with relatively large penumbra and relatively small infarct core are thought to be the most likely to benefit from reperfusion therapies. Major trials have been both negative and positive in testing this heuristic. This has largely depended on the ratio of penumbra volume to core infarct volume i.e. the mismatch ratio. When the mismatch has a binary definition (mismatch or not) a mismatch cutoff of >60ml [42] or ratio > 1.8 [43] has supported the strategy of reperfusion while using smaller mismatch ratios of 1.2–1.4 have produced conflicting results.

The EPITHET and DEFUSE trials defined patients with mismatch as those with a penumbra/core ratio of 1.2 or greater. In both trials, patients were treated in a late 3–6 hour time window. In EPITHET, tPA resulted in more frequent reperfusion, less infarct growth, and better outcomes than placebo. In DEFUSE, there was a favorable clinical response to acute thrombolytics in patients with mismatch but not in those without mismatch. In DIAS and DEDAS trials patients with mismatch greater than 1.2 were treated at a late time point (3–9 hours) with 2 doses of desmoteplase. In these trials, desmoteplase had better reperfusion and clinical outcomes than placebo. However using this same ratio based definition of mismatch, DIAS-2 failed to confirm a benefit of desmoteplase. When the data from these three trials was pooled, there was a trend in benefit (p =0.08) for desmoteplase over placebo. If the minimum mismatch was defined volumetrically as greater than 60ml, desmoteplase had a significant benefit over placebo.

In DEFUSE-2 patients received endovascular intervention up to 12 hours from stroke onset regardless of mismatch profile. Reperfusion was associated with good clinical outcome in patients with target mismatch (perfusion/diffusion ratio of 1.8 or higher), but not in those without target mismatch [43]. MR-RESCUE was an endovascular reperfusion trial that showed no difference between standard medical care and endovascular intervention in all patients regardless of a favorable or unfavorable penumbral pattern [44]. Again the mismatch ratio was relatively small in this negative trial with a penumbra to core ratio of about 1.4.

Assessment of the presence of robust collaterals perfusing penumbral tissue

Vast networks of arterial and venous collaterals can be recruited to support penumbral tissue during acute stroke. Strategies such as permissive hypertension, hypervolemia, and the use of vasopressors are commonly used in clinical practice despite a paucity of evidence to suggest their utility. While none of these strategies have been adequately studied, the degree to which they may augment cerebral perfusion is likely accomplished through collateral flow. Additionally, it has been postulated that collateral flow may facilitate washout of occlusive and partially occlusive emboli [45].

The support of collateral flow is a specific goal of external counterpulsation which enhances coronary circulation collaterals and is currently under investigation in ischemic stroke as well [46]. The status of an acute patient’s collateral flow has great impact on the potential success of interventional therapy. Patients with robust collaterals are more likely to have successful endovascular reperfusion, less likely to have hemorrhagic transformation with endovascular intervention, and more likely to have good outcomes than patients with poor collaterals [47], [48], [49], [50]. Therefore, there is a clinical need to assess collaterals with neuroimaging when making decisions about reperfusion.

While conventional cerebral angiography is the gold standard to characterize and quantify these alternative flow routes [51], other more readily available, non-invasive imaging methods provide fast, effective estimation for purposes of clinical management.. Contrast enhanced CTA, contrasted MRA and non-contrasted MRA may provide evidence of the presence or absence of collaterals, a means of grading collaterals, and the potential origin of collateralized flow [49], [52]. CTA’s major limitation is primarily the computationally intensive generation of maximal intensity projections. MRA is largely limited to identifying collaterals at the circle of Willis. Apart from dedicated vessel imaging, FLAIR imaging of vascular hyperintensity may also provide useful information about the presence of collateralized vessels [52].

Dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion with CT or MR as well as more direct measures of tissue perfusion such as Xenon-enhanced CT, SPECT and PET may show an area of slow blood flow at the periphery of the proximally occluded vessel’s territory. However, this finding only implies collateral flow in the periphery as these methods provide a metric of blood flow at any particular voxel but no direct information about its arterial origin. Non-contrast arterial spin labeled perfusion MRI may also show a peripheral predominance of delayed arterial transit suggestive of prominent collateralized flow which can be graded for a particular arterial vascular territory [52], [53], [54].

III. Specific imaging findings should prompt consideration of non-thrombolytic endovascular treatment strategies

Imaging findings of thrombus size correlation with outcome and response to thrombolytic therapy

Both structural CT and MRI methods have been used to estimate clot size in patients presenting with acute ischemic infarction. The presence of CT hyperintensity within the proximal MCA, known as the hyperdense/hyperintense MCA sign (HIMCAS), is known to indicate an arterial occlusion [55]. The susceptibility vessel sign (SVS) on MRI GRE likewise indicates the presence of occlusive thrombus in the MCA [56]. Indeed these CT and MRI findings correlate closely with each other [57]. The presence of thrombi in smaller vessels including M2 branches has been demonstrated with CT [58] and validated with angiography [59]. Thrombi are likewise detectable in the posterior circulation [60] and intracranial carotid arteries [61]. The clot burden score based on CT imaging was developed to define the extent and location of a thrombus in the anterior circulation by scoring clot located in the ICA, ACA, proximal and distal MCA and M2 MCA segments [49].

The presence of a thrombus on structural imaging has been correlated with poor outcome. Prior to routine treatment with tPA, the presence of HIMCAS was associated with larger stroke, higher NIHSS, and worse outcome [62]. Additionally, MCA thrombus was found to associate with early tissue changes on CT and poor outcome [63].

Despite the advent of routine tPA therapy for acute infarct patients, outcomes have remained worse in stroke patients presenting with a HIMCAS or SVS. In the large SITS-ISTR registry of patients receiving tPA, the presence of HIMCAS was associated with worse presenting NIHSS and worse outcomes, including lower independence and higher mortality [64]. The clot burden score has likewise been associated with worse outcomes and final infarct size despite tPA administration [65]. The presence of HIMCAS over 10 mm in length was associated with poor recanalization rates after tPA [66], and SVS was associated with poor recanalization after tPA in a second cohort [67]. TPA remains the standard of care for this population [68] because a significant number of patients will improve with this therapy despite large clot.

Neuroimaging information regarding the composition of the clot and likelihood of successful mechanical reperfusion

Endovascular therapies provide various approaches for potential treatment of acute ischemic stroke. The mechanisms for removing thrombi include aspiration and mechanical retrieval using coils or stents, and the susceptibility of different clots of different composition to mechanical intervention is an area of active investigation.

A histological analysis has shown that HIMCAS or SVS associated thrombi have a higher percent composition of red blood cells, while those unassociated have a predominance of fibrin [69]. Previous studies have shown significant heterogeneity of the structure of red blood cells, platelets, fibrin and nucleated blood cells [70]. HIMCAS associated thrombi have been found to be more amenable to recanalization with the Merci endovascular device than those seen as isodense on CT [71]. A similar finding was made that found that clots with lower density on non-contrast CT were associated with lower rates of successful recanalization in patients receiving both thrombolytic and endovascular therapies [72]. The reason for the difference in successful recanalization in these cases is not entirely clear.

Additional studies combining histological analysis and structural imaging data will need to be performed in order to definitively correlate thrombus composition with neuroimaging findings. Moreover, the effectiveness of stent retriever devices for clots of different composition types will need to be systematically studied in order to predict the effectiveness of these newer endovascular devices for thrombi of different types.

Sonothrombolysis is an alternative method currently under investigation and in use for the dissolution of clots in the acute setting. A review of the randomized and non-randomized trials involving sonothrombolysis have shown improved recanalization rates and improved outcomes, and larger randomized controlled trials are indicated to fully establish its effectiveness [73]. A recent in vitro study showed better ultrasonic clot dissolution in clots with lower fibrin concentration [74]. In vivo studies relating sonothrombolysis effectiveness with clot composition will need to be performed to confirm its clinical significance.

IV. Identification of unique mechanisms of acute stroke

Imaging identification of acute carotid or vertebrobasilar dissection leading to specific treatment

In patients presenting with acute stroke, a history of neck pain, relatively young age, or lack of other likely mechanism for embolism may increase suspicion of carotid or vertebral artery dissection. The high spatial and temporal resolution of conventional angiography makes this technique the reference standard for diagnosis of dissection [75]. The classic finding of an intimal flap at the proximal margin of the dissection or a double lumen is seen in less than 10% of cases, and the more common findings on angiography are a distal dissecting aneurysm (25–35%) or a tapered narrowing of the artery (65%) [75]. Conventional angiography does not convey information regarding the nature of an intramural hematoma, and narrowing seen can be mistaken for atherosclerosis [76]. Moreover, conventional angiography is an invasive procedure carrying a small, yet significant risk of complication [77].

CT- and MRI-based methods are now in routine use for the diagnosis of suspected dissection. CT/CTA methods describe the shape of the arterial lumen and the presence of arterial wall thickening with high resolution but are associated with significant ionizing radiation. MRI/MRA methods describe the true lumen at a lower resolution but additionally offer information regarding the diffusion restricted intracerebral lesions and the presence of methemoglobin within a thrombosed false lumen of the dissection using T2* fat-saturated sequences [78]. Technical advances in multi-detector CT and CTA image reconstruction as well as time-resolved MRA and MRI hardware advances have improved the sensitivity of both methods. Although some groups have suggested that CT-based methods have some edge in dissection detection, particularly for vertebral arteries [78, 79], currently there is no definitive evidence that favors either CT-based or MR-based methods for the diagnosis of carotid or vertebral artery dissection [80]. Ultrasound techniques are also used for the identification of vertebral and carotid dissection.

Patients presenting with ischemic stroke and carotid artery dissections have worse outcomes after tPA than those patients without dissection, yet the rate of complications including intracranial hemorrhage is not higher in the dissection population [81]. As such, tPA for patients presenting within the treatment window is generally indicated regardless of the presence of dissection. The decision to initiate either antithrombotic or anticoagulation in the acute stroke patient with dissection is typically made after considering the size of the infarct and apparent presence of a thrombus at the dissection site. Owing to the lack of randomized controlled trials, there is no clear evidence for the treatment of dissection with antiplatelet or anticoagulation in acute ischemic stroke [82, 83]. The ongoing randomized CADISS study has been undertaken to address this particular question.

Endovascular stenting has been investigated for patients presenting with acute ischemic stroke and dissection. Case series have shown stenting to have a high rate of successful stent placement and low recurrence of stroke [84, 85]. Complications including TIA, intimal tears, and hematoma formation were noted, and the vessel was noted to re-occlude in a number of patients. At this point, stent placement for patients with acute dissection is not routinely performed due to lack of available outcome data [86].

Identification of malignant MCA syndrome and early management measures

Large territory MCA infarcts resulting from a proximal middle cerebral or internal carotid artery infarct results in edema leading to progressive neurologic deterioration and death in 50–70% of cases, and is termed “malignant MCA syndrome” [87, 88]. Diffusion-weighted and perfusion MRI within 6 hours of onset of symptoms has been noted to predict the development of malignant MCA syndrome with high positive and negative predictive value with DWI volumes of greater than 82 ml [89]. Multiple early parenchymal CT signs including obscuration of the lentiform nucleus, insular ribbon sign, and sulcal effacement have been found to be predictive of large territory MCA infarct [63].

Numerous randomized controlled trials have looked at the benefit of craniotomy for prevention of fatal or disabling outcomes in the presence of neuroimaging findings consistent with malignant MCA syndrome. A pooled analysis of three European trials (DECIMAL, DESTINY, HAMLET) looked at outcomes in patients younger than 60 presenting with DWI lesions greater than 145 ml or CT evidence of a greater than 50% MCA lesion receiving hemicraniectomy within 48 hours or conservative management [90]. A dramatic increase in rate of survival was found for those patients who underwent surgery. Further analysis of the final HAMLET trial results demonstrated that patients who underwent surgery had an absolute risk reduction of 16% in likelihood of severe long-term functional disability [91]. Additionally, early surgical decompression (<6 hours from presentation) was associated with lower mortality (8.3%) compared to late (~3 days from presentation) or no decompression [92].

Despite the clear survival benefit for patients presenting with large MCA territory infarcts, a number of questions remain regarding management of these patients [93]. First, the evidence for improved functional outcomes, especially in terms of independence with activities of daily living, is less robust than the survival benefit and must be weighed when making the decision for early surgical intervention. Second, the randomized studies have been performed on patients less than 60 years of age, and a benefit in patients greater than 60 is not clear.

Identification of posterior circulation infarcts and specific management considerations

Up to twenty percent of ischemic infarcts involve the posterior circulation. Prompt identification of these patients allows consideration of specific treatment strategies. The constellation of presenting symptoms in posterior circulation infarcts including focal weakness, depressed consciousness, autonomic dysfunction, jerking movements in the case of basilar ischemia, and bulbar signs can make the diagnosis of acute ischemic stroke challenging in many of these cases. Therefore, neuroimaging may be especially needed in discerning etiology of posterior circulation syndromes. Non-contrast CT is typically insensitive for posterior fossa infarcts due to beam hardening artifact, with the sensitivity only 42% in one series of patients with confirmed posterior fossa infarcts [94]. In another series of patients presenting with symptoms concerning for a posterior fossa syndrome, non-contrast CT was felt to be a satisfactory modality in 80% of cases [95]. Other clues to the presence of a posterior fossa infarct include the presence of a hyperdense basilar artery sign [96]. IV tPA remains the standard treatment for patients with posterior circulation infarcts [97], but endovascular therapy with stent retrieval systems show high rates of recanalization [98], even if randomized trials have not been performed to establish improved clinical outcomes.

The identification of an acute cerebellar infarct is particularly important because it, if large enough or associated with significant edema, can lead to brainstem compression. In patients who have been correctly identified as having a posterior circulation infarct, follow up neuroimaging can identify compression of the fourth ventricle, hydrocephalus, or deformity of the brain stem [99]. In patients with neuroimaging evidence of brainstem compression or hydrocephalus and a declining neurologic exam, management options include extraventricular drainage and suboccipital decompressive craniotomy. There is no clear evidence favoring either approach owing to the lack of systematic clinical trials [100], but suboccipital decompressive craniotomy does appear to be a safe approach for malignant cerebellar infarction [101].

V. Investigational approaches for neuroimaging that may offer additional important information to guide intervention

Perfusion data can be obtained in the angiography suite, thus bypassing the pre-angiogram multimodality CT or MRI

Flat panel detector angiography is a method using a rotational C-arm mounted flat panel detector to reconstruct high-resolution three-dimensional images in the angiography suite. Flat panel detector angiography is able to generally describe the anatomy of the cerebral parenchyma, but the quality is not high enough to evaluate for hypoattenuation or other signs of acute infarct [102]. Flat panel detector angiography measures of cerebral blood volume were found to correlate well with those of CT perfusion [103]. A proposal has been to potentially bring patients directly to the angiogram suite for perfusion and vessel imaging with flat panel angiography to assess for potential endovascular intervention if future technical development and clinical trials support such a method [104].

Resting state functional MRI used to assess tissue viability and potential for recovery

Functional MRI methods can be used to describe the functionally connected networks that are active at rest. In a recent study Golestani et al obtained resting state MRI for stroke patients acutely and after 90 days [105]. In patients with motor symptoms, inter-hemispheric connectivity was impaired, and in patients with recovery of motor function, connectivity was re-established. A second study showed disruption of the attentional resting state network correlating with neglect after non-dominant hemisphere stroke [106]. Resting state MRI remains a research protocol, but in the future this approach could predict ultimate outcomes or guide functional therapies such as transcranial magnetic stimulation [107].

Diffusion tensor imaging to assess potential for recovery within white matter tracts

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is a technique that uses six or more isotropic diffusion weighted images to describe the microstructural integrity of axons within white matter. White matter tractography is a post-processing technique applied to DTI that allows for the mathematical reconstruction of white matter tracts. DTI tractography applied to patients at an acute-to-subacute timepoint of less than 12 hours after symptom onset focused on pyramidal tract integrity and found that disrupted white matter integrity correlated closely with motor function outcome [108]. Other studies have correlated subacute stroke DTI findings of arcuate fasciculus microstructural integrity with language outcome [108]. Interestingly, use of the increased number of diffusion weighted images in DTI has been shown to have increased sensitivity for acute ischemic stroke [109]. At this point DTI remains a research imaging protocol, but this method is currently under investigation as a marker of potential functional outcome and as a marker of ischemia in acute ischemic stroke.

Additional technical imaging developments that have the potential to improve stroke neuroimaging in the near future

Ultra-high field MRI at 7 Tesla has been used for clinical research studies for the past several years. Owing to the higher field strength, this technique offers higher spatial resolution. A study of subacute and chronic stroke patients imaged at 7T has shown improved resolution of FLAIR, T2 and T2* images [110]. Moreover, MR angiography offers the potential for markedly improved resolution of distal vessels, including M2 and M3 MCA branches [110], and the resolution offers the potential for evaluating individual lenticulostriate arteries [111]. Ultra-high field MRI is not ready for routine clinical use for a number of reasons, including peripheral nervous system stimulation, uncertain safety characteristics of stents or other implants safe at 3 Tesla, and increased field artifacts at air-brain interfaces and at the cerebral periphery [112].

High resolution imaging of the arterial vessel wall is an approach under investigation. This approach uses T2- or FLAIR-weighed MRI for the evaluation of vessel wall and is able to differentiate arterial stenosis from atherosclerotic plaque in MCA [113] and basilar arteries [114]. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI has been used to identify carotid atherosclerotic plaques that are affected by inflammation [115], and imaging characteristics of carotid arteries have been correlated with subsequent infarct [116]. The improved resolution with 7T MRI allows for vessel wall analysis in smaller vessels and in vessels that do not have atherosclerotic plaques [117]. High-resolution vessel wall imaging is not used for routine clinical decision-making, but this approach has the promise of offering detailed information that could lead to different interventions.

More sophisticated analysis of multiple neuroimaging findings resulting in improved acute stroke management

Multiparametric models combining CT perfusion values or a combination of structural T2, perfusion and diffusion MRI data have been used to predict the eventual size of infarct [118]. One recent study demonstrated an accuracy of 74% for a multiparametric model using diffusion and perfusion MRI data [119]. Other approaches have used regional as opposed to voxelwise [120] or neural network analytic [121] approaches.

At this point, these advanced models have not been systematically used to guide therapy decisions. Additional predictive modeling with patient historical and clinical data in combination with structural and perfusion imaging data may serve to improve the identification of patients who may benefit from medical or endovascular interventions.

CONCLUSIONS

This review highlights the numerous neuroimaging methods that may aid in the sequential decision-making process of acute ischemic stroke management. Most commonly, neuroimaging provides rapid and vital information regarding eligibility for and feasibility of medical and/or endovascular reperfusion. For patients presenting with symptoms consistent with stroke, both MRI and CT modalities yield reliable evidence about the presence of intracranial hemorrhage. Additionally, they both aid in determination of infarcted and at risk brain tissue, and they may help predict the risk of reperfusion injury after successful vessel recanalization. Moreover, there is promise that MRI may be used as a surrogate for time when ischemic stroke duration is unknown, thereby expanding eligibility for acute stroke treatment.

The utility of neuroimaging goes beyond informing the decision of whether to implement reperfusion therapy or not. Initially, it is useful in the identification of etiologies that may clinically mimic stroke. In addition, it plays a critical role in surgical planning and management of life-threatening and/or large territory strokes, as well as in identifying large-vessel vasculopathies such as dissection. The past few decades have seen remarkable strides in the diagnosis and management of acute ischemic stroke through the advent of novel imaging techniques, medical treatments and promising endovascular therapies. Ongoing development and refinement of diagnostic imaging innovations will only continue to further this remarkable progress.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work has been funded by NIH-National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Awards NIH/NINDS P50NS044378, K24NS072272, R01NS077706, R13NS082049.

Footnotes

Conflict(s) of Interest/Disclosure(s)

Jason Tarpley declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

Dan Franc declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

Aaron P Tansy declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

David S Liebeskind is a scientific consultant regarding trial design and conduct to Stryker (modest) and Covidien (modest).

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

* Of importance

** Of major importance

- 1.Kidwell CS, Chalela JA, Saver JL, Starkman S, Hill MD, Demchuk AM, Butman JA, Patronas N, Alger JR, Latour LL, et al. Comparison of MRI and CT for detection of acute intracerebral hemorrhage. JAMA. 2004;292(15):1823–1830. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.15.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noguchi K, Ogawa T, Seto H, Inugami A, Hadeishi H, Fujita H, Hatazawa J, Shimosegawa E, Okudera T, Uemura K. Subacute and chronic subarachnoid hemorrhage: diagnosis with fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery MR imaging. Radiology. 1997;203(1):257–262. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.1.9122404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohamed M, Heasly DC, Yagmurlu B, Yousem DM. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MR imaging and subarachnoid hemorrhage: not a panacea. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25(4):545–550. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Latchaw RE, Alberts MJ, Lev MH, Connors JJ, Harbaugh RE, Higashida RT, Hobson R, Kidwell CS, Koroshetz WJ, Mathews V, et al. Recommendations for imaging of acute ischemic stroke: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Stroke. 2009;40(11):3646–3678. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.192616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edgell RC, Vora NA. Neuroimaging markers of hemorrhagic risk with stroke reperfusion therapy. Neurology. 79(13 Suppl 1):S100–104. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182695848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, Toni D, Lesaffre E, von Kummer R, Boysen G, Bluhmki E, Hoxter G, Mahagne MH, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute hemispheric stroke. The European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS) JAMA. 1995;274(13):1017–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demaerschalk BM, Silver B, Wong E, Merino JG, Tamayo A, Hachinski V. ASPECT scoring to estimate >1/3 middle cerebral artery territory infarction. Can J Neurol Sci. 2006;33(2):200–204. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100004972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill MD, Demchuk AM, Tomsick TA, Palesch YY, Broderick JP. Using the baseline CT scan to select acute stroke patients for IV-IA therapy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27(8):1612–1616. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albers GW, Thijs VN, Wechsler L, Kemp S, Schlaug G, Skalabrin E, Bammer R, Kakuda W, Lansberg MG, Shuaib A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging profiles predict clinical response to early reperfusion: the diffusion and perfusion imaging evaluation for understanding stroke evolution (DEFUSE) study. Ann Neurol. 2006;60(5):508–517. doi: 10.1002/ana.20976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhatt A, Vora NA, Thomas AJ, Majid A, Kassab M, Hammer MD, Uchino K, Wechsler L, Jovin TG, Gupta R. Lower pretreatment cerebral blood volume affects hemorrhagic risks after intra-arterial revascularization in acute stroke. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(5):874–878. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000333259.11739.AD. discussion 878–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta R, Yonas H, Gebel J, Goldstein S, Horowitz M, Grahovac SZ, Wechsler LR, Hammer MD, Uchino K, Jovin TG. Reduced pretreatment ipsilateral middle cerebral artery cerebral blood flow is predictive of symptomatic hemorrhage post-intra-arterial thrombolysis in patients with middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 2006;37(10):2526–2530. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000240687.14265.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warach S, Latour LL. Evidence of reperfusion injury, exacerbated by thrombolytic therapy, in human focal brain ischemia using a novel imaging marker of early blood-brain barrier disruption. Stroke. 2004;35(11 Suppl 1):2659–2661. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000144051.32131.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hom J, Dankbaar JW, Soares BP, Schneider T, Cheng SC, Bredno J, Lau BC, Smith W, Dillon WP, Wintermark M. Blood-brain barrier permeability assessed by perfusion CT predicts symptomatic hemorrhagic transformation and malignant edema in acute ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 32(1):41–48. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Senior K. Microbleeds may predict cerebral bleeding after stroke. Lancet. 2002;359(9308):769. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07911-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nighoghossian N, Hermier M, Adeleine P, Derex L, Dugor JF, Philippeau F, Ylmaz H, Honnorat J, Dardel P, Berthezene Y, et al. Baseline magnetic resonance imaging parameters and stroke outcome in patients treated by intravenous tissue plasminogen activator. Stroke. 2003;34(2):458–463. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000053850.64877.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiehler J, Albers GW, Boulanger JM, Derex L, Gass A, Hjort N, Kim JS, Liebeskind DS, Neumann-Haefelin T, Pedraza S, et al. Bleeding risk analysis in stroke imaging before thromboLysis (BRASIL): pooled analysis of T2*-weighted magnetic resonance imaging data from 570 patients. Stroke. 2007;38(10):2738–2744. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.480848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee SH, Bae HJ, Kwon SJ, Kim H, Kim YH, Yoon BW, Roh JK. Cerebral microbleeds are regionally associated with intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2004;62(1):72–76. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000101463.50798.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lam WW, So NM, Wong KS, Rainer T. B0 images obtained from diffusion-weighted echo planar sequences for the detection of intracerebral bleeds. J Neuroimaging. 2003;13(2):99–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu CY, Chiang IC, Lin WC, Kuo YT, Liu GC. Detection of intracranial hemorrhage: comparison between gradient-echo images and b0 images obtained from diffusion-weighted echo-planar sequences on 3. 0T MRI. Clin Imaging. 2005;29(3):155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2004.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JT, Park MS, Yoon W, Cho KH. Detection and significance of incidental unruptured cerebral aneurysms in patients undergoing intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. J Neuroimaging. 22(2):197–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2010.00560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moseley ME, Kucharczyk J, Mintorovitch J, Cohen Y, Kurhanewicz J, Derugin N, Asgari H, Norman D. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of acute stroke: correlation with T2-weighted and magnetic susceptibility-enhanced MR imaging in cats. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1990;11(3):423–429. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoehn-Berlage M, Eis M, Back T, Kohno K, Yamashita K. Changes of relaxation times (T1, T2) and apparent diffusion coefficient after permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat: temporal evolution, regional extent, and comparison with histology. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34(6):824–834. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venkatesan R, Lin W, Gurleyik K, He YY, Paczynski RP, Powers WJ, Hsu CY. Absolute measurements of water content using magnetic resonance imaging: preliminary findings in an in vivo focal ischemic rat model. Magn Reson Med. 2000;43(1):146–150. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(200001)43:1<146::aid-mrm18>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24*.Thomalla G, Cheng B, Ebinger M, Hao Q, Tourdias T, Wu O, Kim JS, Breuer L, Singer OC, Warach S, et al. DWI-FLAIR mismatch for the identification of patients with acute ischaemic stroke within 4.5 h of symptom onset (PRE-FLAIR): a multicentre observational study. Lancet Neurol. 10(11):978–986. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70192-2. This study showed that FLAIR positivity on MRI can be a predictor of stroke onset. With variable onset to FLAIR positivity, this sets up the idea of a ‘tissue clock’ that may be more relevant than the time clock. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jovin TG, Liebeskind DS, Gupta R, Rymer M, Rai A, Zaidat OO, Abou-Chebl A, Baxter B, Levy EI, Barreto A, et al. Imaging-based endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke due to proximal intracranial anterior circulation occlusion treated beyond 8 hours from time last seen well: retrospective multicenter analysis of 237 consecutive patients. Stroke. 42(8):2206–2211. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.604223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schramm P, Schellinger PD, Klotz E, Kallenberg K, Fiebach JB, Kulkens S, Heiland S, Knauth M, Sartor K. Comparison of perfusion computed tomography and computed tomography angiography source images with perfusion-weighted imaging and diffusion-weighted imaging in patients with acute stroke of less than 6 hours’ duration. Stroke. 2004;35(7):1652–1658. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000131271.54098.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keedy A, Soares B, Wintermark M. A pictorial essay of brain perfusion-CT: not every abnormality is a stroke! J Neuroimaging. 22(4):e20–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2012.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szabo K, Poepel A, Pohlmann-Eden B, Hirsch J, Back T, Sedlaczek O, Hennerici M, Gass A. Diffusion-weighted and perfusion MRI demonstrates parenchymal changes in complex partial status epilepticus. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 6):1369–1376. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hedna VS, Stead LG, Bidari S, Patel A, Gottipati A, Favilla CG, Salardini A, Khaku A, Mora D, Pandey A, et al. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) and CT perfusion changes. Int J Emerg Med. 5:12. doi: 10.1186/1865-1380-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato K, Shimizu H, Fujimura M, Inoue T, Matsumoto Y, Tominaga T. Compromise of brain tissue caused by cortical venous reflux of intracranial dural arteriovenous fistulas: assessment with diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Stroke. 42(4):998–1003. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.597203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katzan IL, Hammer MD, Hixson ED, Furlan AJ, Abou-Chebl A, Nadzam DM. Utilization of intravenous tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(3):346–350. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.3.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith EE, Fonarow GC, Reeves MJ, Cox M, Olson DM, Hernandez AF, Schwamm LH. Outcomes in mild or rapidly improving stroke not treated with intravenous recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator: findings from Get With The Guidelines-Stroke. Stroke. 42(11):3110–3115. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.613208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barber PA, Zhang J, Demchuk AM, Hill MD, Buchan AM. Why are stroke patients excluded from TPA therapy? An analysis of patient eligibility. Neurology. 2001;56(8):1015–1020. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.8.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajajee V, Kidwell C, Starkman S, Ovbiagele B, Alger JR, Villablanca P, Vinuela F, Duckwiler G, Jahan R, Fredieu A, et al. Early MRI and outcomes of untreated patients with mild or improving ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2006;67(6):980–984. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000237520.88777.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kidwell CS, Saver JL, Starkman S, Duckwiler G, Jahan R, Vespa P, Villablanca JP, Liebeskind DS, Gobin YP, Vinuela F, et al. Late secondary ischemic injury in patients receiving intraarterial thrombolysis. Ann Neurol. 2002;52(6):698–703. doi: 10.1002/ana.10380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kidwell CS, Saver JL, Mattiello J, Starkman S, Vinuela F, Duckwiler G, Gobin YP, Jahan R, Vespa P, Kalafut M, et al. Thrombolytic reversal of acute human cerebral ischemic injury shown by diffusion/perfusion magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol. 2000;47(4):462–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olivot JM, Mlynash M, Thijs VN, Kemp S, Lansberg MG, Wechsler L, Bammer R, Marks MP, Albers GW. Optimal Tmax threshold for predicting penumbral tissue in acute stroke. Stroke. 2009;40(2):469–475. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.526954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calamante F, Christensen S, Desmond PM, Ostergaard L, Davis SM, Connelly A. The physiological significance of the time-to-maximum (Tmax) parameter in perfusion MRI. Stroke. 41(6):1169–1174. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.580670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teng MM, Cheng HC, Kao YH, Hsu LC, Yeh TC, Hung CS, Wong WJ, Hu HH, Chiang JH, Chang CY. MR perfusion studies of brain for patients with unilateral carotid stenosis or occlusion: evaluation of maps of “time to peak” and “percentage of baseline at peak”. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001;25(1):121–125. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200101000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wintermark M, Flanders AE, Velthuis B, Meuli R, van Leeuwen M, Goldsher D, Pineda C, Serena J, van der Schaaf I, Waaijer A, et al. Perfusion-CT assessment of infarct core and penumbra: receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in 130 patients suspected of acute hemispheric stroke. Stroke. 2006;37(4):979–985. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000209238.61459.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamalian S, Konstas AA, Maas MB, Payabvash S, Pomerantz SR, Schaefer PW, Furie KL, Gonzalez RG, Lev MH. CT perfusion mean transit time maps optimally distinguish benign oligemia from true “at-risk” ischemic penumbra, but thresholds vary by postprocessing technique. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 33(3):545–549. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Warach S, Al-Rawi Y, Furlan AJ, Fiebach JB, Wintermark M, Lindsten A, Smyej J, Bharucha DB, Pedraza S, Rowley HA. Refinement of the magnetic resonance diffusion-perfusion mismatch concept for thrombolytic patient selection: insights from the desmoteplase in acute stroke trials. Stroke. 43(9):2313–2318. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.642348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43*.Lansberg MG, Straka M, Kemp S, Mlynash M, Wechsler LR, Jovin TG, Wilder MJ, Lutsep HL, Czartoski TJ, Bernstein RA, et al. MRI profile and response to endovascular reperfusion after stroke (DEFUSE 2): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 11(10):860–867. In this study, reperfusion was associated with good clinical outcome in patients with perfusion/diffusion mismatch but not in those with no mismatch. Contrary to MR RESCUE, this suggests that there is strong reason to believe that perfusion imaging can identify patients who stand to benefit from endovascular reperfuson. [Google Scholar]

- 44*.Kidwell CS, Jahan R, Gornbein J, Alger JR, Nenov V, Ajani Z, Feng L, Meyer BC, Olson S, Schwamm LH, et al. A trial of imaging selection and endovascular treatment for ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 368(10):914–923. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212793. This MR RESCUE study showed that endovascular thrombectomy was not beneficial for patients with penumbral pattern or non-penumbral pattern on perfusion imaging. Contrary to the DEFUSE study, this suggests little utility of using perfusion imaging to select appropriate patients for endovascular reperfusion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caplan LR, Hennerici M. Impaired clearance of emboli (washout) is an important link between hypoperfusion, embolism, and ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol. 1998;55(11):1475–1482. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.11.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alexandrov AW, Ribo M, Wong KS, Sugg RM, Garami Z, Jesurum JT, Montgomery B, Alexandrov AV. Perfusion augmentation in acute stroke using mechanical counter-pulsation-phase IIa: effect of external counterpulsation on middle cerebral artery mean flow velocity in five healthy subjects. Stroke. 2008;39(10):2760–2764. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.512418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47*.Bang OY, Saver JL, Kim SJ, Kim GM, Chung CS, Ovbiagele B, Lee KH, Liebeskind DS. Collateral flow predicts response to endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 42(3):693–699. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595256. This study demonstrated a correlation between collateral grade and reperfusion score with endovascular therapy. More robust collaterals predicted better reperfusion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48*.Bang OY, Saver JL, Kim SJ, Kim GM, Chung CS, Ovbiagele B, Lee KH, Liebeskind DS. Collateral flow averts hemorrhagic transformation after endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 42(8):2235–2239. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.604603. This study showed that good collaterals decrease the risk of reperfusion related hemorhage across all reperfusion scores. This and the study above suggest that collateral status should be strongly considered when making the clinical decision to give reperfusion therapies or not. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tan IY, Demchuk AM, Hopyan J, Zhang L, Gladstone D, Wong K, Martin M, Symons SP, Fox AJ, Aviv RI. CT angiography clot burden score and collateral score: correlation with clinical and radiologic outcomes in acute middle cerebral artery infarct. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(3):525–531. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kucinski T, Koch C, Eckert B, Becker V, Kromer H, Heesen C, Grzyska U, Freitag HJ, Rother J, Zeumer H. Collateral circulation is an independent radiological predictor of outcome after thrombolysis in acute ischaemic stroke. Neuroradiology. 2003;45(1):11–18. doi: 10.1007/s00234-002-0881-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Higashida RT, Furlan AJ, Roberts H, Tomsick T, Connors B, Barr J, Dillon W, Warach S, Broderick J, Tilley B, et al. Trial design and reporting standards for intra-arterial cerebral thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2003;34(8):e109–137. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000082721.62796.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liebeskind DS. Collateral circulation. Stroke. 2003;34(9):2279–2284. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000086465.41263.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chng SM, Petersen ET, Zimine I, Sitoh YY, Lim CC, Golay X. Territorial arterial spin labeling in the assessment of collateral circulation: comparison with digital subtraction angiography. Stroke. 2008;39(12):3248–3254. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.520593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu B, Wang X, Guo J, Xie S, Wong EC, Zhang J, Jiang X, Fang J. Collateral circulation imaging: MR perfusion territory arterial spin-labeling at 3T. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29(10):1855–1860. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gacs G, Fox AJ, Barnett HJ, Vinuela F. CT visualization of intracranial arterial thromboembolism. Stroke. 1983;14(5):756–762. doi: 10.1161/01.str.14.5.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rovira A, Orellana P, Alvarez-Sabin J, Arenillas JF, Aymerich X, Grive E, Molina C, Rovira-Gols A. Hyperacute ischemic stroke: middle cerebral artery susceptibility sign at echo-planar gradient-echo MR imaging. Radiology. 2004;232(2):466–473. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2322030273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sakamoto Y, Kimura K, Sakai K. M1 susceptibility vessel sign and hyperdense middle cerebral artery sign in hyperacute stroke patients. Eur Neurol. 2012;68(2):93–97. doi: 10.1159/000338308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barber PA, Demchuk AM, Hudon ME, Pexman JH, Hill MD, Buchan AM. Hyperdense sylvian fissure MCA “dot” sign: A CT marker of acute ischemia. Stroke. 2001;32(1):84–88. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leary MC, Kidwell CS, Villablanca JP, Starkman S, Jahan R, Duckwiler GR, Gobin YP, Sykes S, Gough KJ, Ferguson K, et al. Validation of computed tomographic middle cerebral artery “dot”sign: an angiographic correlation study. Stroke. 2003;34(11):2636–2640. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000092123.00938.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krings T, Noelchen D, Mull M, Willmes K, Meister IG, Reinacher P, Toepper R, Thron AK. The hyperdense posterior cerebral artery sign: a computed tomography marker of acute ischemia in the posterior cerebral artery territory. Stroke. 2006;37(2):399–403. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000199062.09010.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ozdemir O, Leung A, Bussiere M, Hachinski V, Pelz D. Hyperdense internal carotid artery sign: a CT sign of acute ischemia. Stroke. 2008;39(7):2011–2016. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.505230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tomsick T, Brott T, Barsan W, Broderick J, Haley EC, Spilker J, Khoury J. Prognostic value of the hyperdense middle cerebral artery sign and stroke scale score before ultraearly thrombolytic therapy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17(1):79–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moulin T, Cattin F, Crepin-Leblond T, Tatu L, Chavot D, Piotin M, Viel JF, Rumbach L, Bonneville JF. Early CT signs in acute middle cerebral artery infarction: predictive value for subsequent infarct locations and outcome. Neurology. 1996;47(2):366–375. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kharitonova T, Ahmed N, Thoren M, Wardlaw JM, von Kummer R, Glahn J, Wahlgren N. Hyperdense middle cerebral artery sign on admission CT scan--prognostic significance for ischaemic stroke patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis in the safe implementation of thrombolysis in Stroke International Stroke Thrombolysis Register. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27(1):51–59. doi: 10.1159/000172634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Puetz V, Dzialowski I, Hill MD, Subramaniam S, Sylaja PN, Krol A, O’Reilly C, Hudon ME, Hu WY, Coutts SB, et al. Intracranial thrombus extent predicts clinical outcome, final infarct size and hemorrhagic transformation in ischemic stroke: the clot burden score. Int J Stroke. 2008;3(4):230–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2008.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shobha N, Bal S, Boyko M, Kroshus E, Menon BK, Bhatia R, Sohn SI, Kumarpillai G, Kosior J, Hill MD, et al. Measurement of Length of Hyperdense MCA Sign in Acute Ischemic Stroke Predicts Disappearance after IV tPA. J Neuroimaging. 2013 doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2012.00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kimura K, Iguchi Y, Shibazaki K, Watanabe M, Iwanaga T, Aoki J. M1 susceptibility vessel sign on T2* as a strong predictor for no early recanalization after IV-t-PA in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2009;40(9):3130–3132. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.552588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tartaglia MC, Di Legge S, Saposnik G, Jain V, Chan R, Bussiere M, Hachinski V, Frank C, Hesser K, Pelz D. Acute stroke with hyperdense middle cerebral artery sign benefits from IV rtPA. Can J Neurol Sci. 2008;35(5):583–587. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100009367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liebeskind DS, Sanossian N, Yong WH, Starkman S, Tsang MP, Moya AL, Zheng DD, Abolian AM, Kim D, Ali LK, et al. CT and MRI early vessel signs reflect clot composition in acute stroke. Stroke. 2011;42(5):1237–1243. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.605576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marder VJ, Chute DJ, Starkman S, Abolian AM, Kidwell C, Liebeskind D, Ovbiagele B, Vinuela F, Duckwiler G, Jahan R, et al. Analysis of thrombi retrieved from cerebral arteries of patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2006;37(8):2086–2093. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000230307.03438.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71*.Froehler MT, Tateshima S, Duckwiler G, Jahan R, Gonzalez N, Vinuela F, Liebeskind D, Saver JL, Villablanca JP For the USI. The hyperdense vessel sign on CT predicts successful recanalization with the Merci device in acute ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg. 2012 doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2012-010313. With ever-changing armamentarium of methods for achieving reperfusion, this study sets a precedent for being able to use imaging to help guide which therapy is used. Therefore imaging should strive to guide not only whether to perform reperfusion but also how to accomplish it. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moftakhar P, English JD, Cooke DL, Kim WT, Stout C, Smith WS, Dowd CF, Higashida RT, Halbach VV, Hetts SW. Density of thrombus on admission CT predicts revascularization efficacy in large vessel occlusion acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2013;44(1):243–245. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.674127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ricci S, Dinia L, Del Sette M, Anzola P, Mazzoli T, Cenciarelli S, Gandolfo C. Sonothrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD008348. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008348.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aftab A, Lyeo L, Zhou Y, Murugappan K, Sharma V. Ultrasound Assisted Thrombolysis For Fresh Clots With Higher Cholesterol Content. International Stroke Conference Poster Abstracts; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Provenzale JM. Dissection of the internal carotid and vertebral arteries: imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165(5):1099–1104. doi: 10.2214/ajr.165.5.7572483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen CJ, Tseng YC, Lee TH, Hsu HL, See LC. Multisection CT angiography compared with catheter angiography in diagnosing vertebral artery dissection. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25(5):769–774. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kaufmann TJ, Huston J, 3rd, Mandrekar JN, Schleck CD, Thielen KR, Kallmes DF. Complications of diagnostic cerebral angiography: evaluation of 19,826 consecutive patients. Radiology. 2007;243(3):812–819. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2433060536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vertinsky AT, Schwartz NE, Fischbein NJ, Rosenberg J, Albers GW, Zaharchuk G. Comparison of multidetector CT angiography and MR imaging of cervical artery dissection. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29(9):1753–1760. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gottesman RF, Sharma P, Robinson KA, Arnan M, Tsui M, Saber-Tehrani A, Newman-Toker DE. Imaging characteristics of symptomatic vertebral artery dissection: a systematic review. Neurologist. 2012;18(5):255–260. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e3182675511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Provenzale JM, Sarikaya B. Comparison of test performance characteristics of MRI, MR angiography, and CT angiography in the diagnosis of carotid and vertebral artery dissection: a review of the medical literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(4):1167–1174. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Engelter ST, Rutgers MP, Hatz F, Georgiadis D, Fluri F, Sekoranja L, Schwegler G, Muller F, Weder B, Sarikaya H, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis in stroke attributable to cervical artery dissection. Stroke. 2009;40(12):3772–3776. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.555953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82**.Kennedy F, Lanfranconi S, Hicks C, Reid J, Gompertz P, Price C, Kerry S, Norris J, Markus HS Investigators C. Antiplatelets vs anticoagulation for dissection: CADISS nonrandomized arm and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2012;79(7):686–689. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318264e36b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lyrer P, Engelter S. Antithrombotic drugs for carotid artery dissection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(10):CD000255. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hassan AE, Zacharatos H, Souslian F, Suri MF, Qureshi AI. Long-term clinical and angiographic outcomes in patients with cervico-cranial dissections treated with stent placement: a meta-analysis of case series. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29(7):1342–13. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kadkhodayan Y, Jeck DT, Moran CJ, Derdeyn CP, Cross DT., 3rd Angioplasty and stenting in carotid dissection with or without associated pseudoaneurysm. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(9):2328–2335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mohan IV. Current Optimal Assessment and Management of Carotid and Vertebral Spontaneous and Traumatic Dissection. Angiology. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0003319712475154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kasner SE, Demchuk AM, Berrouschot J, Schmutzhard E, Harms L, Verro P, Chalela JA, Abbur R, McGrade H, Christou I, et al. Predictors of fatal brain edema in massive hemispheric ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2001;32(9):2117–2123. doi: 10.1161/hs0901.095719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Berrouschot J, Sterker M, Bettin S, Koster J, Schneider D. Mortality of space-occupying (‘malignant’) middle cerebral artery infarction under conservative intensive care. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24(6):620–623. doi: 10.1007/s001340050625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Thomalla G, Hartmann F, Juettler E, Singer OC, Lehnhardt FG, Kohrmann M, Kersten JF, Krutzelmann A, Humpich MC, Sobesky J, et al. Prediction of malignant middle cerebral artery infarction by magnetic resonance imaging within 6 hours of symptom onset: A prospective multicenter observational study. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(4):435–445. doi: 10.1002/ana.22125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vahedi K, Hofmeijer J, Juettler E, Vicaut E, George B, Algra A, Amelink GJ, Schmiedeck P, Schwab S, Rothwell PM, et al. Early decompressive surgery in malignant infarction of the middle cerebral artery: a pooled analysis of three randomised controlled trials. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(3):215–222. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91**.Hofmeijer J, Kappelle LJ, Algra A, Amelink GJ, van Gijn J, van der Worp HB Investigators H. Surgical decompression for space-occupying cerebral infarction (the Hemicraniectomy After Middle Cerebral Artery infarction with Life-threatening Edema Trial [HAMLET]): a multicentre, open, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(4):326–333. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70047-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cho DY, Chen TC, Lee HC. Ultra-early decompressive craniectomy for malignant middle cerebral artery infarction. Surg Neurol. 2003;60(3):227–232. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(03)00266-0. discussion 232–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wartenberg KE. Malignant middle cerebral artery infarction. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2012;18(2):152–163. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32835075c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hwang DY, Silva GS, Furie KL, Greer DM. Comparative sensitivity of computed tomography vs. magnetic resonance imaging for detecting acute posterior fossa infarct. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(5):559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.05.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Teasdale GM, Hadley DM, Lawrence A, Bone I, Burton H, Grant R, Condon B, Macpherson P, Rowan J. Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in suspected lesions in the posterior cranial fossa. BMJ. 1989;299(6695):349–355. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6695.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Goldmakher GV, Camargo EC, Furie KL, Singhal AB, Roccatagliata L, Halpern EF, Chou MJ, Biagini T, Smith WS, Harris GJ, et al. Hyperdense basilar artery sign on unenhanced CT predicts thrombus and outcome in acute posterior circulation stroke. Stroke. 2009;40(1):134–139. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.516690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Montavont A, Nighoghossian N, Derex L, Hermier M, Honnorat J, Philippeau F, Belo M, Turjman F, Adeleine P, Froment JC, et al. Intravenous r-TPA in vertebrobasilar acute infarcts. Neurology. 2004;62(10):1854–1856. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000125330.06520.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mordasini P, Brekenfeld C, Byrne JV, Fischer U, Arnold M, Heldner MR, Ludi R, Mattle HP, Schroth G, Gralla J. Technical feasibility and application of mechanical thrombectomy with the Solitaire FR Revascularization Device in acute basilar artery occlusion. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(1):159–163. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Koh MG, Phan TG, Atkinson JL, Wijdicks EF. Neuroimaging in deteriorating patients with cerebellar infarcts and mass effect. Stroke. 2000;31(9):2062–2067. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.9.2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Juttler E, Schweickert S, Ringleb PA, Huttner HB, Kohrmann M, Aschoff A. Long-term outcome after surgical treatment for space-occupying cerebellar infarction: experience in 56 patients. Stroke. 2009;40(9):3060–3066. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.550913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pfefferkorn T, Eppinger U, Linn J, Birnbaum T, Herzog J, Straube A, Dichgans M, Grau S. Long-term outcome after suboccipital decompressive craniectomy for malignant cerebellar infarction. Stroke. 2009;40(9):3045–3050. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.550871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102*.Struffert T, Deuerling-Zheng Y, Kloska S, Engelhorn T, Strother CM, Kalender WA, Kohrmann M, Schwab S, Doerfler A. Flat detector CT in the evaluation of brain parenchyma, intracranial vasculature, and cerebral blood volume: a pilot study in patients with acute symptoms of cerebral ischemia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31(8):1462–1469. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2083. By piloting perfusion imaging in the angiography suite, this study introduces a paradigm of performing diagnostic perfusion imaging at the ‘point of care’. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103**.Struffert T, Deuerling-Zheng Y, Engelhorn T, Kloska S, Golitz P, Kohrmann M, Schwab S, Strother CM, Doerfler A. Feasibility of cerebral blood volume mapping by flat panel detector CT in the angiography suite: first experience in patients with acute middle cerebral artery occlusions. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33(4):618–625. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Strother CM. The Neurointerventional Suite as an Acute Stroke Intervention Unit. Endovascular Today. 2012:38–40. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Golestani AM, Tymchuk S, Demchuk A, Goodyear BG, Group V-S. Longitudinal evaluation of resting-state FMRI after acute stroke with hemiparesis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2013;27(2):153–163. doi: 10.1177/1545968312457827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.He BJ, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Epstein A, Shulman GL, Corbetta M. Breakdown of functional connectivity in frontoparietal networks underlies behavioral deficits in spatial neglect. Neuron. 2007;53(6):905–918. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Carter AR, Shulman GL, Corbetta M. Why use a connectivity-based approach to study stroke and recovery of function? Neuroimage. 2012;62(4):2271–2280. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Puig J, Pedraza S, Blasco G, Daunis IEJ, Prados F, Remollo S, Prats-Galino A, Soria G, Boada I, Castellanos M, et al. Acute damage to the posterior limb of the internal capsule on diffusion tensor tractography as an early imaging predictor of motor outcome after stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(5):857–863. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Harris AD, Pereira RS, Mitchell JR, Hill MD, Sevick RJ, Frayne R. A comparison of images generated from diffusion-weighted and diffusion-tensor imaging data in hyper-acute stroke. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;20(2):193–200. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Madai VI, von Samson-Himmelstjerna FC, Bauer M, Stengl KL, Mutke MA, Tovar-Martinez E, Wuerfel J, Endres M, Niendorf T, Sobesky J. Ultrahigh-field MRI in human ischemic stroke--a 7 tesla study. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kang CK, Park CA, Park CW, Lee YB, Cho ZH, Kim YB. Lenticulostriate arteries in chronic stroke patients visualised by 7 T magnetic resonance angiography. Int J Stroke. 2010;5(5):374–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.van der Kolk AG, Hendrikse J, Zwanenburg JJ, Visser F, Luijten PR. Clinical applications of 7T MRI in the brain. Eur J Radiol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Li ML, Xu WH, Song L, Feng F, You H, Ni J, Gao S, Cui LY, Jin ZY. Atherosclerosis of middle cerebral artery: evaluation with high-resolution MR imaging at 3T. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204(2):447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Turan TN, Rumboldt Z, Brown TR. High-resolution MRI of basilar atherosclerosis: three-dimensional acquisition and FLAIR sequences. Brain Behav. 2013;3(1):1–3. doi: 10.1002/brb3.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]