Abstract

A number of mechanisms have been proposed to contribute to the selective neuronal cell loss observed during Alzheimer disease (AD). These include the formation and accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ)-containing plaques, neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), and inflammatory processes mediated by astrocytes and microglia. Neuronal responses to such insults in AD brain include increased protein levels and immunoreactivity for kinases known to regulate cell cycle progression. One downstream target of these cell cycle regulatory proteins, the Retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product (pRb), has been shown to exhibit altered expression patterns in AD. Furthermore, in vitro studies have implicated pRb and one of the transcription factors it regulates, E2F1, in Aβ-induced cell death. To further explore the role of these proteins in AD, we examined the distribution of the E2F1 transcription factor and the hyperphosphorylated form of pRb (ppRb), which is unable to bind and regulate E2F activity, in the cortex of patients with AD and in non-demented controls. We observed increased ppRb and E2F1 immunoreactivity in AD brain, with ppRb predominately located in the nucleus and E2F1 in the cytoplasm. Although neither of these proteins significantly co-localized with NFTs, both ppRb and E2F1 were found in cells surrounding a subset of Aβ-containing plaques. These results support a role for G1 to S phase cell cycle regulators in AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, Amyloid plaque, Cell cycle, E2F1, Retinoblastoma protein, Transcription factor

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer disease (AD) is characterized by neuronal cell loss and the accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ)-con-taining neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) within specific brain regions during disease progression (1, 2). While genetic mutations have been identified in many familial forms of AD (3), the initiating factors in sporadic AD remain unknown. Numerous molecular mechanisms have been proposed to account for the observed neuronal dysfunction that occurs during AD, including the abnormal phosphorylation and aggregation of cytoskeletal proteins, accumulation and deposition of Aβ, synaptic degeneration, oxidative injury, defects in energy metabolism, and inflammation (4–9). Yet none of these can solely justify the pathology and progressive nature of the disease.

Several of the proposed mechanisms share common downstream targets in cell cycle proteins within neuronal and non-neuronal cells (10–13). It has been proposed that neurons re-enter the cell cycle during AD, which induces cell death pathways. Activation of several cell cycle regulators in post-mitotic neurons has been shown to induce apoptosis in a variety of in vitro models (14–19). Consistent with the in vitro findings, several proteins that function in cell cycle regulation also exhibit altered patterns of expression in post-mitotic neurons in AD brain, suggesting a role of cell cycle proteins in neuronal cell death during AD (20–22). These proteins include multiple cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), cyclin D1, cyclin B, Ki67, and even cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors such as p16 and p21 (23–28). Interestingly, many of these cell cycle proteins that are typically found in the nucleus are located in the cytoplasm of neurons in AD brain, suggesting alternative functions for cell cycle proteins in AD.

Entry into the cell cycle requires activation of G1 to S phase cell cycle proteins. Key regulators of the cell cycle include members of the retinoblastoma (pRb) and E2F gene families (29). Members of the E2F gene family bind DNA and activate transcription as a heterodimer with DP proteins (30). Transactivational activity of E2F: DP complexes is directly repressed by protein:protein interactions with the pRb protein (29). Hyperphosphorylation of pRb via the appropriate cyclin/CDK complex liberates the E2F:DP complex and induces gene expression and progression through S phase of the cell cycle (29). E2F1 and pRb proteins not only function in the control of cell proliferation, but recent data indicate that they also participate in cell death mechanisms (29, 31, 32). E2F1-induced apoptosis has been shown to occur by either transcription-dependent or -independent mechanisms (33, 34), and can be inhibited by the expression of dominant negative DP-1 protein or pRb (12, 35, 36). Both pRb and E2F1 also play important roles in regulating neuronal cell death during development, as loss of pRb function in transgenic mice results in extensive cell loss in the central nervous system (37). Concomitant mutation of E2F1 significantly suppresses abnormal apoptosis observed in pRb knockout embryos, indicating that E2F1 induces neuronal cell death in the absence of functional pRb (38).

Various in vitro models have also demonstrated a role for pRb and E2F1 in neuronal cell death. E2F1 and pRb have been shown to play an important role in neuronal death evoked by DNA damage or low K+ (32, 36). Addition of Aβ peptide to cultured neurons induces CDK-dependent phosphorylation of pRb prior to cell death (12, 39–41). Inhibition of E2F activity via expression of a dominant negative form of DP-1 reduces Aβ-induced neuronal cell death, suggesting the importance of E2F DNA binding activity during Aβ toxicity. Therefore the activation of cell cycle proteins, including phosphorylation of pRb and liberation of E2F1, plays an important role in Aβ or DNA damage-induced cell death of cultured neurons. However the ability of Aβ to induce pRb phosphorylation in vivo has not been determined.

Since Aβ induces pRb phosphorylation in vitro and aberrant CDK4 expression occurs in neurons within affected brain regions during AD (25, 42), we hypothesized that Aβ deposition induces hyperphosphorylation of pRb and subsequent release of E2F1 during AD. Recently, altered staining patterns of pRb phosphorylation on Ser795 (ppRb) were reported in neurodegenerative diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis (SIVE) (43, 44). In the current study we examined the expression patterns of hyperphosphorylated pRb and E2F1 in AD brain. We observed increased immunoreactivity for both ppRb and E2F1 in affected cortical brain regions in AD, with increased protein levels of ppRb during AD as shown by immunoblot. While neurons containing NFTs were largely devoid of either ppRb or E2F1 staining, neurons and activated astrocytes that surround subsets of Aβ-contain-ing plaques were immunoreactive for ppRb and E2F1. Our results support pRb and E2F1 as targets of cellular responses within both neurons and astrocytes to Aβ deposition during AD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Brain Tissues and Cases

Fresh-frozen and formalin-fixed tissue samples were obtained at the time of autopsy from 29 cases, 18 of which were clinically and neuropathologically defined as AD, and 11 non-demented age-matched controls (Table). Approval for use of human tissues was obtained from the University of Pittsburgh Internal Review Board. The average age at death was 65 yr for controls (age range: 52–85 yr), and 80 yr for AD cases (age range: 62–93 yr). The average postmortem interval was 5 h (h) for the AD cases (range: 2–10 h) and 9 h for the control cases (range: 4–19 h). Neuropathologic studies to confirm the clinical diagnosis included examination of neocortical, hippocampal, basal forebrain, and cerebellar tissues. CERAD criteria (2) and NIA-Reagan Institute guidelines were used to classify each case. All samples were provided by the University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center.

TABLE.

Case Samples and Immunohistochemistry Results

| Case | Age/Gender | PMI (h) | ppRb | E2F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer | ||||

| AD1 | 93/M | 4.5 | 2 | 1 |

| AD2 | 78/M | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| AD3 | 80/M | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| AD4 | 88/F | 5.5 | 1 | 1 |

| AD5 | 83/F | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| AD6 | 80/F | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| AD7 | 90/F | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| AD8 | 76/F | 10 | 2 | 2 |

| AD9 | 62/M | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| AD10 | 82/F | 6 | 1 | 0 |

| AD11 | 83/F | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| AD12 | 80/M | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| AD13 | 81/F | 7 | 2 | 2 |

| AD14 | 65/M | 8 | 2 | 2 |

| AD15 | 82/M | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| AD16 | 81/M | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| AD17 | 79/M | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| AD18 | 82/F | 6 | 2 | 1 |

| Control | ||||

| C1 | 54/M | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| C2 | 65/M | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| C3 | 60/M | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| C4 | 52/M | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| C5 | 63/F | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| C6 | 74/M | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| C7 | 75/M | 10 | 1 | 0 |

| C8 | 85/M | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| C9 | 72/F | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| C10 | 53/M | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| C11 | 59/F | 6 | 0 | 0 |

PMI = postmortem interval. Scoring scale: 0 = no immunoreactivity; 1 = low to moderate numbers of positive cells in either the white or gray matter; 2 = numerous immunoreactive cells in both the gray and white matter.

Immunoblot Analysis

Protein extracts were prepared from frozen tissue samples and separated by electrophoresis on 10% SDS-PAGE gels as previously described (43). Equal amounts of protein were loaded onto the gel lanes. The resulting blot was blocked in 5% non-fat milk in PBS (phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4) for 1 h before incubation in primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies were diluted in 0.5% milk/PBS and concentrations used were as follows: anti-phosphoserine pRB (pSer795, New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) at 1:1,000 dilution; anti-pRb (14001A from PharMingen, San Diego, CA; IF8 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at 1:500 dilution; anti-E2F1 (sc-251 or sc-193, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:750 dilution; or anti-actin (Zymed, South San Francisco, CA) at 1:2,000 dilution. The blots were washed extensively in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 before incubation in HRP-conjugated isotype-specific secondary antibodies at 1: 1,000 dilution in 0.5% milk/PBS for 1 h at room temperature. After additional PBS/Tween washes, the antibodies were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) (Renaissance, NEN Life Science Products Inc., Boston, MA). Two different antibodies to pRb or E2F1 were used since these proteins were near the level of detection by immunoblot analysis from tissue extracts. Individual protein bands were quantified using NIH Image software and single-factor ANOVA analysis.

Microscopy

Ten-µm paraffin sections were first microwaved in Citra antigen retrieval solution (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA) for 4 min at high power and 6.5 min at 50% power, and then cooled to room temperature over 2 h. Sections were then incubated in 3% H2O2 + 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS (phosphate buffered saline) for 30 min. The sections were blocked in 5% milk/PBS for 1 h. Primary antibody was added in 0.5% milk/PBS and incubated overnight at 4°C. For light microscopy, antibodies included anti-pSer795 (ppRb) at 1:40 dilution, or anti-E2F1 (sc-251, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:50 dilution. After washes in PBS, sections were incubated in biotinylated secondary antibodies specific for each of the primary antibodies (1:750 dilution) for 1.5 h. Upon washing the sections were incubated in streptavidin-HRP (1:1,000 dilution) for 1 h and the reaction product visualized with AEC. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

For double label confocal microscopy, sections were first incubated overnight with anti-MAP2 (SMI 52, Sternberger Monoclonals, Inc., Lutherville, MD) at 1:1,000 dilution to label neurons; anti-GFAP at 1:500 dilution (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) to label activated astrocytes; 4G8 at 1:500 dilution to label Aβ plaques; or MC1 (provided by Dr. Peter Davies, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York) at 1:20 dilution to label neurofibrillary pathology. Each antibody was detected using the appropriate FITC conjugated secondary antibody used at 1:500 dilution. After extensive washes in PBS, tissues were then incubated overnight with either anti-phosphoserine795 ppRb at 1: 40 dilution or anti-E2F1 (sc-251, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:50 dilution. After extensive washes in PBS, sections were incubated with anti-rabbit-Biotin (1:500 dilution for ppRb detection) or anti-mouse IgG2a-Biotin (1:500 dilution for E2F1) for 1.5 h. The sections were washed extensively in PBS and incubated in streptavidin-Cy5 (1:1,000 dilution) for 1 h, washed extensively, and mounted onto slides in Gelvatol. The slides were analyzed on a Molecular Dynamics Model 2001 laser scanning confocal microscope. Omission of the primary antibody resulted in absence of fluorescent signal. Crossover control experiments were also performed for each primary antibody against the secondary antibody from the other label in order to determine the specificity of the secondary antibody.

RESULTS

Cellular Distribution of ppRb in AD

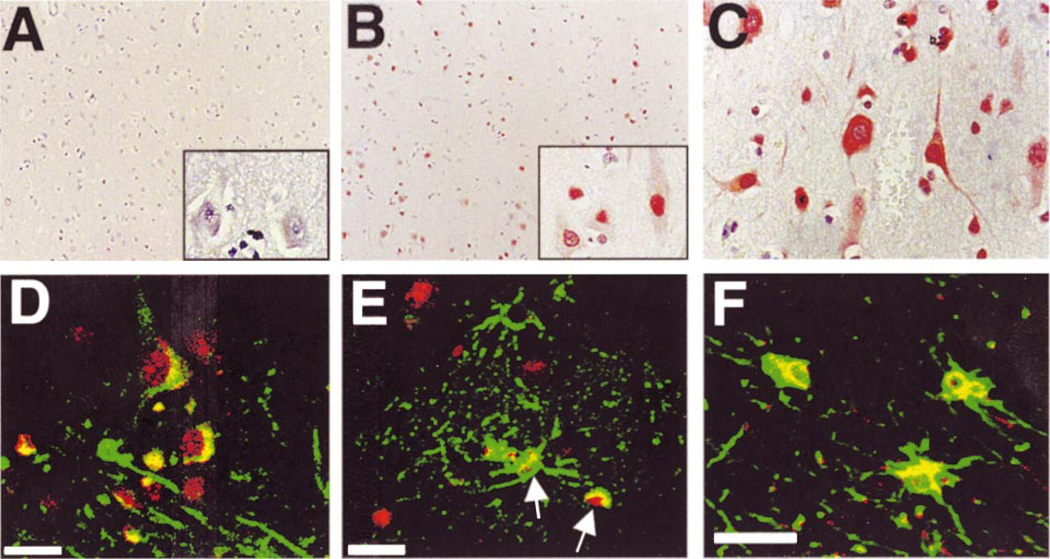

Increased levels of ppRb have been observed in neurons involved in other neurodegenerative diseases including ALS and encephalitis associated with lentiviral infection of both humans and macaques (HIVE and SIVE) (43, 44). Since many cell cycle proteins exhibit increased immunoreactivity in AD brain, we examined the distribution of ppRb in the cortex of control and AD patients (Table). Positive ppRb staining was present in all 18 AD cases assessed, whereas only 3 of 11 non-demented, agematched controls exhibited ppRb immunostaining (Fig. 1A, B). In AD midfrontal and temporal cortex, ppRb was present within the nuclei of cells that morphologically resemble neurons, in addition to nuclei of smaller cells that may be either neurons or glia (Fig. 1B). ppRb immunoreactivity was also observed in the cytoplasm of pyramidal neurons (Fig. 1C). Though ppRb was present in cells distributed throughout all cortical layers in AD cases (Fig. 1B), staining was most robust in the large pyramidal neurons of layers III and V.

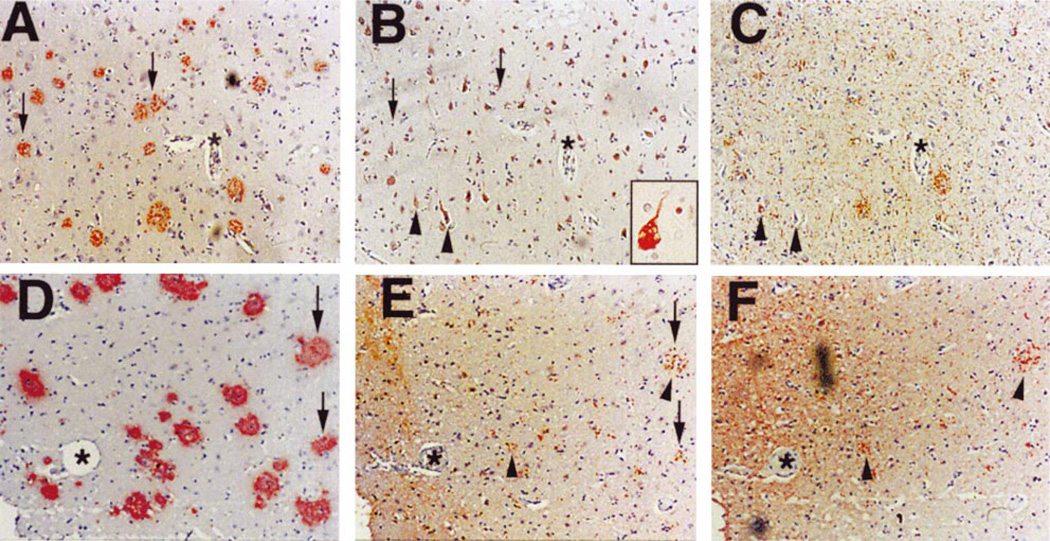

Fig. 1.

Localization of ppRb in AD cortex. The immunolocalization of ppRb was determined in midfrontal and temporal cortex of non-demented control and AD patients by light microscopy (A–C) and double label laser scanning confocal microscopy (D–F). A: Lack of ppRb immunoreactivity in midfrontal cortex of a non-demented aged individual. The tissue is counterstained with hematoxylin. Inset is a higher magnification. The panel is representative of case C11 in the Table. B: Distribution of ppRb (red) in numerous cells throughout the cortical layers in AD patients. Inset demonstrates nuclear distribution of ppRb (case AD6). C: ppRb localization in the nucleus and cytoplasm of pyramidal neurons of AD brain (case AD8). D: Co-localization of ppRb (red) in MAP2 (green) labeled neurons. Additional non-neuronal cells also exhibit ppRb immunoreactivity (case AD8). E: ppRb (red) is contained in a subset of GFAP immunoreactive astrocytes (green) surrounding plaque structures in cortical gray matter (arrows). F: ppRb (red) is located in the nuclear and peri-nuclear region of GFAP labeled astrocytes (green) in the white matter. Panels (E) and (F) are from case AD3 of the Table. Magnifications: A, B = ×100; C, and insets = ×400. Scale bar = 20 µm in panels D–F.

Cell types exhibiting ppRb staining were confirmed by double label immunofluorescent confocal microscopy for ppRb and MAP2 for neurons or GFAP for astrocytes. In AD ppRb staining was nuclear in MAP2-positive neurons (Fig. 1D) and a subset of activated astrocytes and neurons surrounding plaque-like structures in AD brain (Fig. 1E). Within the white matter, ppRb was present in the nuclear and peri-nuclear region of many GFAP-positive astrocytes (Fig. 1F). Similar results were observed in the temporal cortex of AD cases (data not shown). While Aβ-containing, diffuse plaques were present in the cerebellum of the AD cases, we failed to observe ppRb immunoreactivity in the cerebellum of control or AD cases (data not shown). Increased levels of ppRb were also not observed in the motor cortex of AD patients (data not shown). These results indicate that ppRb immunoreactivity occurs in both neurons and astrocytes within affected cortical brain regions in AD.

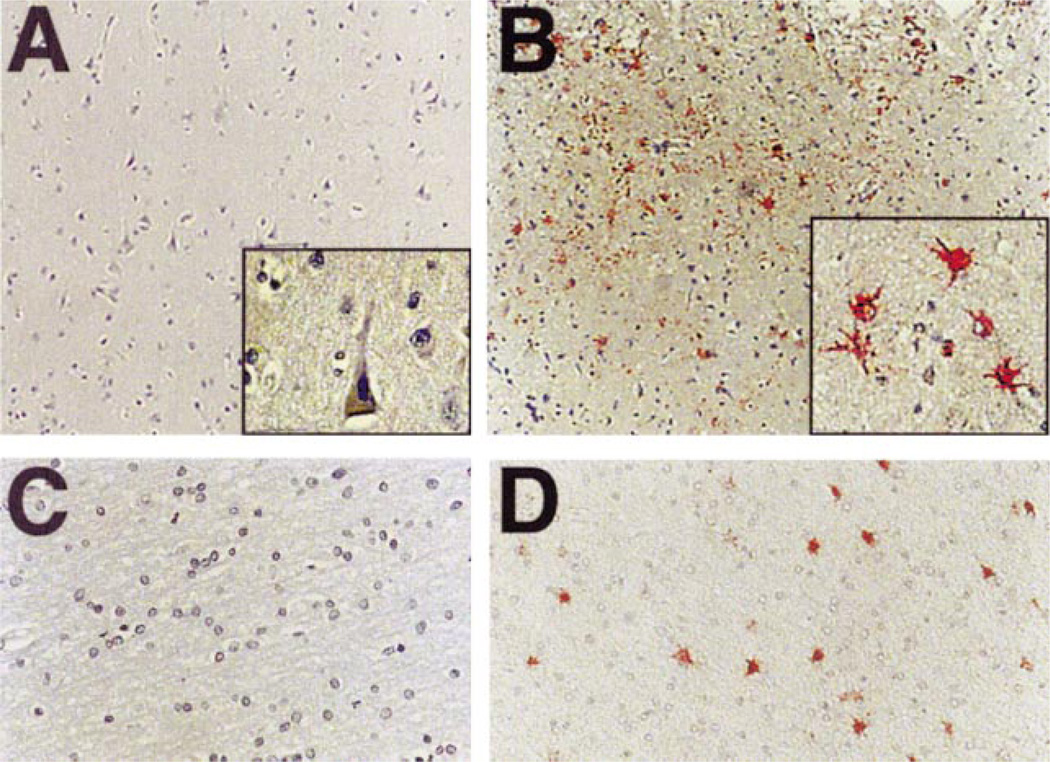

Cellular Distribution of E2F1 During AD

Phosphorylation of pRb results in liberation of the transcription factor E2F1, which has also been shown to exhibit altered staining patterns in ALS, SIVE, and HIVE (43, 44). As in previous models, E2F1 protein was not detected in either cortical gray or white matter of agematched control subjects (Fig. 2A, 2C), although a small number of E2F1-positive cells were present near the pial surface in 3 of 11 controls. In cortical gray matter of AD patients, E2F1 staining was observed in the cytoplasm of cells and surrounding plaque-like structures (Fig. 2B). Increased numbers of E2F1 immunoreactive cells were noted around Aβ plaque structures in layers II and VI. Within cortical white matter, E2F1 staining was observed in the nucleus and cytoplasm of cells in AD cases (Fig. 2D). E2F1-immunoreactive cells were observed in 15 of 18 AD cases, often located in the white matter and surrounding plaque structures within the deep layers of the cortex (data not shown). We did not detect E2F1 staining in the cerebellum or motor cortex of either control or AD cases (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of E2F1 in AD brain. The immunolocalization of E2F1 was determined in midfrontal and temporal cortex of non-demented control and AD patients by light microscopy. A: E2F1 immunoreactivity is absent in midfrontal cortex of non-demented aged individuals. Inset is a high power magnification. B: E2F1 (red) is localized in the cytoplasm of cells that often surround plaque-like structures in AD patients (inset). C: The subcortical white matter is devoid of E2F1 immunoreactivity in non-demented, aged individuals. D: E2F1 distribution in white matter in AD patients. Magnifications: A, B = ×100; C, D = ×200; insets = ×400. Cases represented in each panel are C6 in panel (A), AD1 in panel (B), C3 in panel (C), and AD7 in panel (D).

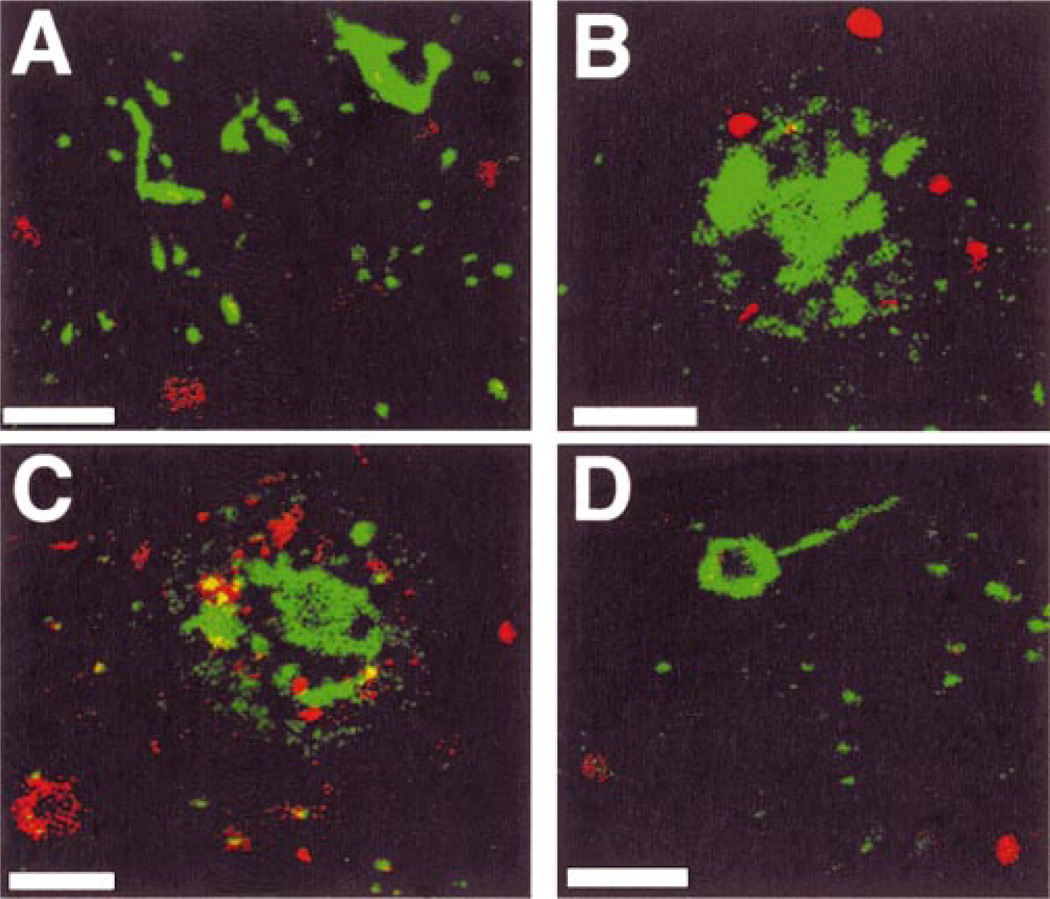

A small number of MAP-2-positive neurons contained cytoplasmic E2F1 as confirmed by double label immunofluorescent confocal laser microscopy (Fig. 3A). Many neurons containing E2F1 immunoreactivity also contained nuclear ppRb (Fig. 3B). E2F1 was also observed in numerous GFAP-containing astrocytes, including astrocytes surrounding plaque-like structures in cortical gray matter (Fig. 3C). A distinct staining pattern was observed in the white matter where E2F1 localized to the nuclear and peri-nuclear region of GFAP-containing astrocytes (Fig. 3D). E2F1-containing astrocytes were also observed contacting blood vessels exhibiting moderate to severe cerebral amyloid angiopathy (data not shown). These findings indicate that increased E2F1 immunoreactivity occurs in astrocytes during AD.

Fig. 3.

Co-localization of E2F1 with ppRb, MAP2 and GFAP in AD brain by double label confocal laser microscopy. A: E2F1 (red) is located in the cytoplasm of MAP2-immuno-reactive neurons (green). B: E2F1 (green) also co-localizes to ppRb-labeled (red) cells. Note the E2F1 is in the cytoplasm of cells marked by nuclear ppRb. C: E2F1 (red) is in the cytoplasm of GFAP immunoreactive astrocytes (green). D: Within the white matter, E2F1 (red) is located to the nucleus and cytoplasm of GFAP-positive astrocytes (green). Panels (A) and (B) are from case AD5 and panels (C) and (D) from case AD10 (Table). Scale bar = 20 µm in all panels.

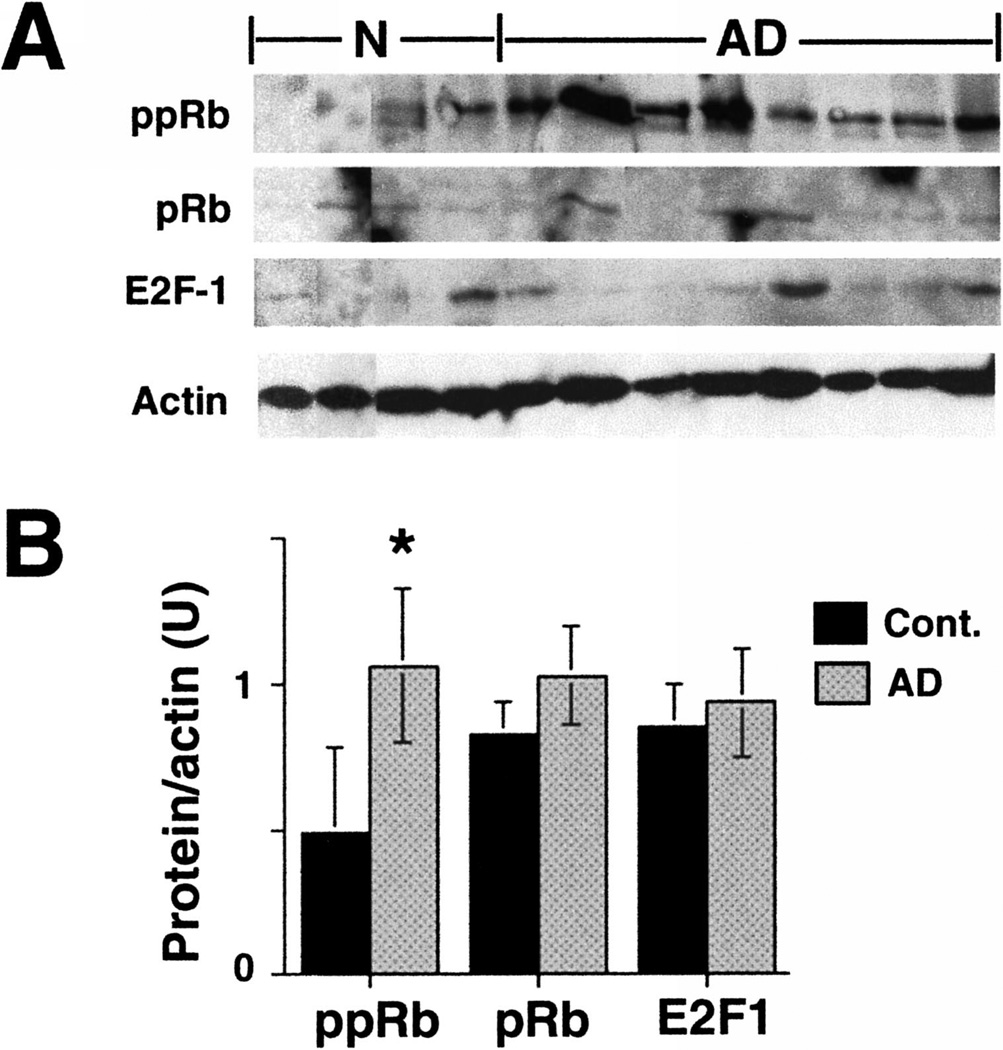

Increased Levels of ppRb in AD by Immunoblot

To determine if immunohistochemical changes in ppRb during AD correlate with increased phosphoprotein levels, protein extracts were prepared from midfrontal cortex of non-demented age-matched control and AD cases. Since both ppRb and E2F1 exhibited altered immunostaining in AD, we examined protein levels of ppRb, pRb and E2F1 by immunoblot analysis. We observed a doublet corresponding to Ser795 phosphorylated pRb proteins that was most prevalent in AD (Fig. 4A). The level of ppRb was significantly increased in the AD cases examined by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 4B). However the level of pRb protein did not statistically change in AD brain (Fig 4), indicating that increased ppRb was most likely due to phosphorylation of pre-existing pRb protein. While E2F1 was near the level of detection by immunoblot analysis, the level of E2F1 protein was not statistically different between the control and AD patients (Fig. 4). Two different antibodies were used to probe for pRb or E2F1 protein by immunoblot (see Materials and Methods).

Fig. 4.

Altered levels of ppRb in AD brain. A: Protein extracts were prepared from midfrontal cortex from 4 non-demented aged controls and 8 AD cases from the Table. 150 µg of protein was loaded into each lane of a 10% SDS-PAGE and probed for ppRb, pRb, E2F1 and actin. B: Quantification of protein levels in each gel lane, normalized to the level of actin protein in each lane. Error bars denote standard deviation within each set. Asterisk (*) indicates significance between the control and AD groups (p < 0.05, as derived from single-factor ANOVA analysis).

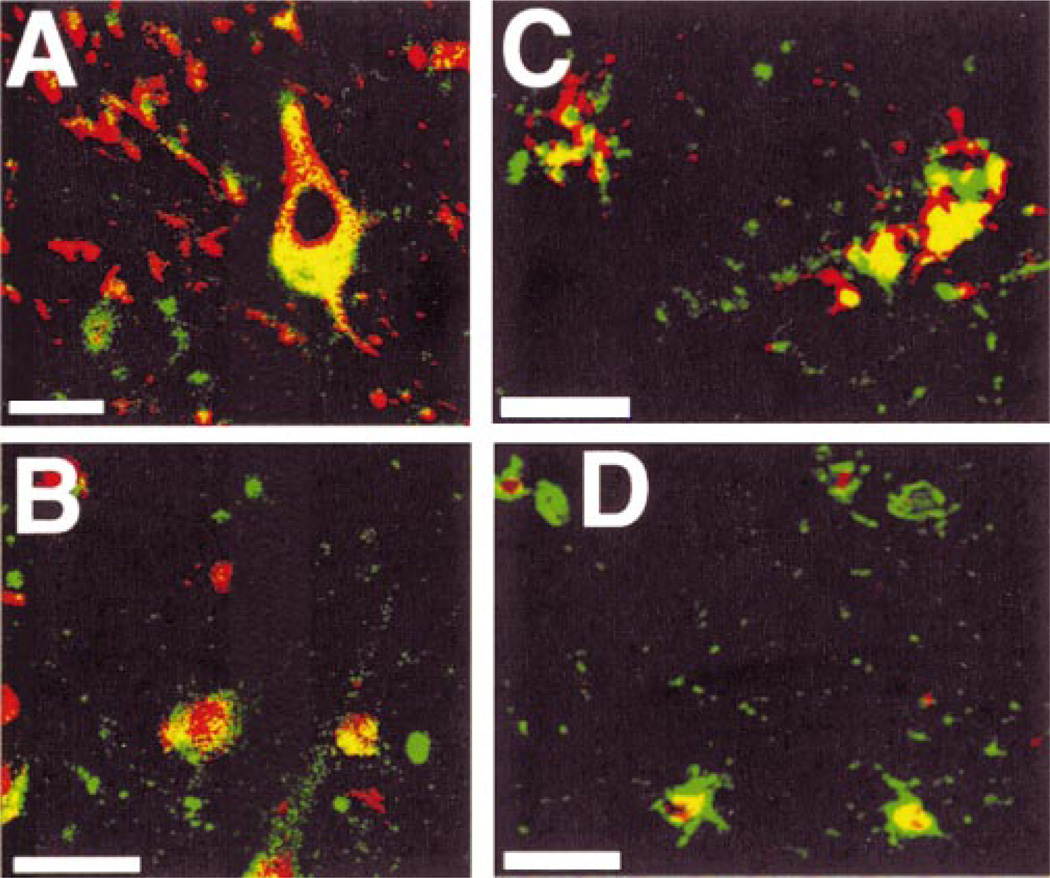

Co-localization of ppRb and E2F1 with Aβ or Hyperphosphorylated Tau

Since the 2 major pathologic hallmarks of AD are Aβ-containing plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau containing NFTs, we examined the distribution of ppRb and E2F1 with reference to these neuropathologic markers by light microscopy. As mentioned above, ppRb was observed within neurons of all cortical layers. However we also noted that ppRb-positive cells surround a subset of Aβ-containing plaques (arrows in Fig. 5A, 5B). These cells typically had ppRb in the cytoplasm. By analyzing 4 low-power fields of the serial sections, approximately 20% of Aβ plaques have ppRb-positive surrounding cells (Fig. 5B, 5C). In AD brain we also observed a small number of ppRb-positive neurons that exhibit a distorted or dystrophic morphology (Inset in Fig. 5B). Such neurons had ppRb in the cytoplasm and co-localized with phos-pho-tau-labeled neurons in consecutive sections (arrowheads in Fig. 5B, 5C). Likewise, E2F1-containing cells surround approximately 15% of Aβ-containing plaques (arrows in Fig. 5D, 5E). These E2F1-positive plaques also contained neuritic pathology identified using antibodies to phospho-tau (arrowheads in Fig. 5E, 5F).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of ppRb and E2F1 immunoreactivity with Aβ plaques and phosphor-tau. Consecutive sections were immunostained for Aβ (A), ppRb (B), and phosphorylated tau (C). Inset in (B) displays a dystrophic neuron containing ppRb in the cytoplasm. D–F: Consecutive sections stained for Aβ, E2F1, and phospho-tau. All sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and the antigen-immune complex depicted in red. Panels (A–C) are from case AD7 and panels (D–F) from case AD2 (Table). Magnifications: all panels, ×100; inset, ×400.

To confirm these data we performed double label confocal laser microscopy. However, ppRb rarely co-localized with a marker for NFTs by double label confocal laser microscopy (Fig. 6A). Instead, we observed ppRbimmunoreactive cells in close proximity to tangle bearing neurons or surrounding Aβ neuritic plaques (Fig. 6B, C). Dystrophic neurites or NFTs within and around the plaques failed to contain ppRb. Likewise, E2F1-immunoreactive cells were localized in close proximity to Aβ-containing plaques but failed to co-localize with neurofibrillary pathology in AD brain (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

E2F1- and ppRb-immunoreactive cells surround a subset of Aβ plaques in AD. A: NFTs (green) were largely devoid of ppRb (red) in AD cortex. B: ppRb-immunoreactive cells (red) were in close proximity to Aβ plaques (green). C: E2F1-immunoreactive cells (red) surround Aβ plaques (green). D: E2F1 does not co-localize to the cytoplasm of neurons containing NFTs. Panel (A) represents case AD8, panel (B) from AD4, panel (C) from AD7 and panel (D) from AD3 (Table). Scale bar = 20 µm in all panels.

DISCUSSION

Recent studies have demonstrated that Aβ induces pRb hyperphosphorylation at serine 795 and E2F1 mediated cell death of cultured neurons (12, 39, 40). Both pRb and E2F1 also participate in neuronal cell death induced by DNA damage (36), and activation of cyclin dependent kinases (CDKs) and increased pRb phosphorylation (ppRb) occurs prior to cell death in animal models of ischemia (45, 46). While prior studies have identified increased expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins in AD brain (21, 25, 28, 47), Aβ-induced cell cycle progression or pRb phosphorylation in vivo has not been determined. A recent study suggested that DNA replication occurs in affected neurons during AD (48), though prior to DNA replication neurons must first pass through the G1 phase of the cell cycle and enter S phase. Progression through the G1 phase is regulated by pRb and E2F1. In the current study we demonstrated the presence of ppRb and E2F1 in both neurons and activated astrocytes in AD brain, often surrounding Aβ-containing plaques. These data indicate that numerous cells have entered the G1 phase of the cell cycle, and suggest that pRb and E2F1 participate in cellular responses to Aβ deposition and may contribute to Aβ-induced cell death pathways during AD.

Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrates increased ppRb staining in neurons and astrocytes during AD. Hyperphosphorylation of pRb typically occurs via the activation of CDKs and increased levels of D and E type cyclins (49). Prior studies have demonstrated increased immunoreactivity for CDK4 and cyclin D proteins in neurons of AD brain, with conflicting reports of the presence or absence of CDK4 immunoreactivity in neurons containing NFTs (23, 25, 26, 42). Therefore ppRb may be generated during AD via activated CDK4/cyclin D. However cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors such as p16 and p21 are also expressed during AD (24, 26, 50). Recent studies have shown that p21 can function to activate CDK4 (51, 52). Whether the interplay between cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors such as p21 and p16 contributes to or impedes the activation of CDK4 and subsequent phosphorylation of pRb during AD warrants further investigation. Additional studies are also required to determine the expression and distribution of CDK4/6, D type cyclins, and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (p16 and p21) with respect to ppRb in AD brain to address the mechanism of ppRb formation. Increased levels of ppRb were also detected in AD brain by immunoblot analysis. The lack of pRb protein accumulation in AD brain suggests that ppRb is formed by the phosphorylation of pre-existing pRb protein by activated kinases. Additional possibilities for the observed increase in ppRb include altered protein-protein interaction or decreased phosphatase activity.

We found few neurons containing NFTs exhibit ppRb immunoreactivity, though abundant ppRb-positive cells are present in the affected regions of AD brain (Fig. 5, Fig. 6). Those neurons exhibiting co-localization of ppRb and phospho-tau had ppRb in the cytoplasm. This suggests that ppRb accumulates independent of, or prior to, NFT formation. It is possible that activated cyclin/CDK phosphorylates pRb in the nucleus, and then translocate to the cytoplasm to assist in the generation of NFTs. Further studies are required to explore this hypothesis. However prior studies have shown co-localization of CDKs with NFTs in AD brain, and CDKs can phosphorylate tau in vitro (47, 53, 54).

Hyperphosphorylation of pRb releases E2F1 and leads to the activation of gene expression, increased proliferation, and/or induction of cell death pathways (29). In AD patients we observed increased E2F1 immunoreactivity in the cytoplasm of astrocytes and neurons in affected cortical brain regions, often surrounding Aβ plaques (Fig. 5, Fig. 6). While not all Aβ plaques have E2F1-positive cells nearby, those cells that contain E2F1 immunoreactivity are near regions of Aβ deposition. These plaques are often neuritic as demonstrated by the presence of phospho-tau epitopes, though neurons containing NFTs rarely exhibit E2F1 immunoreactivity. The presence of cytoplasmic E2F1 in areas of amyloid plaque pathology may signify cellular responses to Aβ deposition and/or neuronal injury. Reactive gliosis and glial proliferation occur during AD (55), and the presence of ppRb and E2F1 in astrocytes surrounding amyloid plaques suggests that these proteins participate in glial responses during AD. Glial cell death has also been noted in AD (56), and therefore E2F1 immunoreactivity in astrocytes surrounding Aβ plaques may also imply a role for E2F1 in glial cell death. Neurons with cytoplasmic E2F1 also contained ppRb, indicating a change in E2F1 distribution in response to pRb phosphorylation and release of E2F1. Abundant E2F1 immunoreactivity was also noted in the nucleus and cytoplasm of cortical white matter cells during AD, concurrent with the presence of ppRb. Since activation of nuclear E2F1 stimulates gene expression and cell cycle progression, our data suggest that glial proliferation may be prevalent within the white matter during AD. The presence of E2F1 in the cytoplasm of neurons and astrocytes also suggests a change in E2F1-dependent transcription during AD, though the exact function of E2F1 in the cytoplasm of glia and neurons during AD warrants further investigation.

Although we could not detect altered levels of E2F1 protein in AD brain by immunoblot, this does not preclude an increase in E2F1 protein within a subset of cells masked by unchanged levels in the majority of cells within the tissue homogenate. Alternatively, the change in E2F1 immunostaining may reflect changes in antigen detection or sub-cellular distribution and not an increase in protein level. Phosphorylation of pRb would liberate E2F1 from the pRb/E2F complex that may make more E2F1 available for detection by immunohistochemical methods. Such a hypothesis is interesting, as it would imply a change in E2F1 activity. This is consistent with observations within in vitro models of AD that require functional E2F1 for cell death.

We have shown that increased ppRb immunoreactivity occurs during AD and is concurrent with a cytoplasmic distribution of E2F1 in cells of the cortical gray and white matter. These observations are consistent with recent findings for E2F1 and ppRb subcellular localization during SIVE and HIVE, where both E2F1 and ppRb exhibit increased staining in the cytoplasm of neurons in encephalitic midfrontal cortex (43). A common feature of AD, HIVE, and SIVE is inflammatory responses during disease progression (6, 57). Immune cell activation leads to the secretion of numerous signaling molecules including cytokines, neurotrophic factors, and chemokines (58). Recently, it has been reported that neurotrophic factors and chemokines induce redistribution of ppRb in neurons and a concomitant increase in protein levels in mixed neuroglial cultures, while E2F1 exhibits only altered subcellular localization in this model system (59). These results reflect our observations in AD brain. Such transient alterations of signaling cascades and cell cycle proteins may represent a regenerative response during early AD, while chronic activation of cell cycle proteins may ultimately favor cell death (14, 20, 60).

We observed both ppRb and E2F1 immunoreactivity in neurons and glia surrounding a subset of amyloid-containing plaques. Increased immunoreactivity for other cell cycle proteins, including p53 and cyclins, has also been observed near Aβ plaque pathology (28, 61). These findings suggest that the formation of amyloid plaques induces multiple intracellular signal transduction pathways in adjacent cells leading to alterations in kinases regulating cell cycle proteins. The increase in ppRb during AD indicates cells are capable of entering the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Since both pRb and E2F1 participate in neuronal development and neuronal cell death, the role of these cell cycle proteins in neuroprotective versus neurodegenerative responses during AD warrants further investigation. Formation of ppRb itself is not likely to be directly toxic to the cell, since ppRb immunoreactivity is widespread in affected brain regions during AD in neurons with a healthy appearance. However, stimulation of cell cycle machinery to the extent that the cell re-enters the cell cycle could instigate neuronal injury leading to progressive neurodegeneration (62). Loss of cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors and activation of CDKs precedes neuronal cell death in an animal model of ischemia (46). Thus, hyperphosporylation of pRb and cytoplasmic localization of E2F1 may contribute to aberrant intracellular signaling mechanisms that initiate responses to cellular injury but ultimately contribute to neuronal cell death after accumulation of further cellular insults (63–65). Continued investigations to determine the signaling pathways and nuclear events that promote neuronal survival or death will lead not only to an increased understanding of molecular mechanisms relevant to neurodegenerative diseases but also to novel therapeutic strategies to maintain cell survival during AD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Susan Scudiere and David Werner for assistance with the immunohistochemistry and Srikanth Ranganathan for assistance with quantitation of the immunoblots.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (AG13208) and the Alzheimer’s Association (PRG-98-039).

REFERENCES

- 1.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D. The consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD). II. Standardization of the neuropathological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lendon CL, Ashall F, Goate AM. Exploring the etiology of Alzheimer disease using molecular genetics. JAMA. 1997;277:825–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lovestone S, Reynolds C. The phosphorylation of tau: A critical stage in neurodevelopment and neurodegenerative processes. Neuroscience. 1997;78:309–324. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00577-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeKosky ST, Scheff SW. Synapse loss in frontal cortex biopsies in Alzheimer’s disease: Correlation with cognitive severity. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:457–464. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGeer PL, McGeer EG. Mechanisms of cell death in Alzheimer disease-immunopathology. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1998;54:159–166. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-7508-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith MA, Sayre LM, Monnier VM, Perry G. Radical AGEing in Alzheimer’s disease. TINS. 1995;18:172–176. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93897-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beal MF. Aging, energy, and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:357–366. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holscher C. Possible causes of Alzheimer’s disease: Amyloid fragments, free radicals, and calcium homeostasis. kNeurobiol Dis. 1998;5:129–141. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherr CJ. G1 phase progression: Cycling on cue. Cell. 1994;79:551–555. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pines J. Four-dimensional control of the cell cycle. Nature Cell Biol. 1999;1:E73–E79. doi: 10.1038/11041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giovanni A, Wirtz-Brugger F, Keramaris E, Slack R, Park DS. Involvement of cell cycle elements, cyclin-dependent kinases, pRb, and E2F-DP, in β-amyloid-induced neuronal death. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19011–19016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park DS, Morris EJ, Stefanis L, et al. Multiple pathways of neuronal death induced by DNA-damaging agents, NGF deprivation, and oxidative stress. J Neurosci. 1998;18:830–840. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-03-00830.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeman RS, Estus S, Johnson EM. Analysis of cell cycle-related gene expression in postmitotic neurons: Selective induction of cyclin D1 during programmed cell death. Neuron. 1994;12:343–355. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kranenburg O, van der Eb AJ, Zanterna A. Cyclin D1 is an essential mediator of apoptotic neuronal cell death. EMBO J. 1996;15:46–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slack RS, Belliveau DJ, Rosenberg M, et al. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of the tumor suppressor p53 induces apoptosis in postmitotic neurons. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1085–1096. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.4.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park DS, Morris EJ, Jaya P, Shelanski ML, Geller HM, Greene LA. Cyclin-dependent kinases participate in death of neurons evoked by DNA-damaging agents. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:457–467. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grilli M, Memo M. Possible role of NF-kappaβ and p53 in the glutamate-induced pro-apoptotic neuronal pathway. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:22–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freeman RS. The cell cycle and neuronal cell death. In: Koliatsos VE, Ratan RR, editors. Cell death and diseases of the nervous system. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press Inc; 1999. pp. 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raina AK, Monteiro MJ, McShea A, Smith MA. The role of cell cycle-mediated events in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Exp Path. 1999;80:71–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.1999.00106.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raina AK, Zhu X, Rottkamp CA, Monteiro M, Takeda A, Smith MA. Cyclin’ toward dementia: Cell cycle abnormalities and abortive oncogenesis in Alzheimer disease. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61:128–133. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000715)61:2<128::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raina AK, Pardo P, Rottkamp CA, Zhu X, Pereira-Smith OM, Smith MA. Neurons in Alzheimer disease emerge from senescence. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;123:3–9. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arendt T, Rodel L, Gartner U, Holzer M. Expression of the cyclindependent kinase inhibitor p16 in Alzheimer’s disease. euroreport. 1996;7:3047–3049. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199611250-00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arendt T, Holzer M, Gartner U. Neuronal expression of cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors of the INK4 family in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Trans. 1998;105:949–960. doi: 10.1007/s007020050104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Busser J, Geldmacher DS, Herrup K. Ectopic cell cycle proteins predict the sites of neuronal cell death in Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2801–2807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02801.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McShea A, Harris PLR, Webster KR, Wahl AF, Smith MA. Abnormal expression of the cell cycle regulators p16 and cdk4 in Alheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:1933–1939. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vincent I, Rosado M, Davies P. Mitotic mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease? J Cell Biol. 1996;13:2413–2425. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.3.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagy Z, Esiri M, Cato A-M, Smith AD. Cell cycle markers in the hippocampus in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1997;94:6–15. doi: 10.1007/s004010050665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Black AR, Azizkhan-Clifford J. Regulation of E2F: A family of transcription factors involved in proliferation control. Gene. 1999;237:281–302. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00305-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Helin K, Wu C, Fattaey A, et al. Heterodimerization of the transcription factors E2F-1 and DP-1 leads to cooperative trans-activation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1850–1861. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.10.1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeGregori J, Leone G, Miron A, Jakoi L, Nevins JR. Distinct roles for E2F proteins in cell growth control and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7245–7250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Hare MJ, Hou ST, Morris EJ, et al. Induction and modulation of cerebellar granule neuron death by E2F-1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25358–25364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001725200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azuma-Hara M, Taniura H, Uetsuki T, Niinobe M, Yoshikawa K. Regulation and deregulation of E2F1 in postmitotic neurons differentiated from embryonal carcinoma P19 cells. Exp Cell Res. 1999;251:442–451. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phillips AC, Ernst MK, Bates S, Rice NR, Vousden KH. E2F-1 potentiates cell death by blocking antiapoptotic signaling pathways. Mol Cell. 1999;4:771–781. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80387-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsieh JK, Fredersdorf S, Kouzarides T, Martin K, Lu X. E2F1-induced apoptosis requires DNA binding but not transactivation and is inhibited by the retinoblastoma protein through direct interaction. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1840–1852. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.14.1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park DS, Morris EJ, Bremner R, et al. Involvement of retinoblastoma family members and E2F/DP complexes in the death of neurons evoked by DNA damage. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3104–3114. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-09-03104.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jacks T, Fazeli A, Schmidt E, Bronson R, Goodell M, Weinberg R. Effects of an Rb mutation in the mouse. Nature. 1992;359:295–300. doi: 10.1038/359295a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsai KY, Hu Y, Macleod KF, Crowley D, Yamasaki L, Jacks T. Mutation of E2F-1 suppresses apoptosis and inappropriate S-phase entry and extends survival of Rb-deficient mouse embryos. Mol Cell. 1998;2:293–304. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80274-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giovanni A, Keramaris E, Morris EJ, et al. E2F1 mediates death of β-amyloid-treated cortical neurons in a manner independent of p53 and dependent on Bax and caspase 3. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11553–11560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Copani A, Condorelli F, Caruso A, et al. Mitotic signaling by β -amyloid causes neuronal death. FASEB J. 1999;13:2225–2234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jordan-Sciutto KL, Rhodes J, Bowser R. Altered subcellular distribution of transcriptional regulators in response to Aβ peptide and during Alzheimer’s disease. Mech Ageing Develop. 2001;123:11–20. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00334-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsujioka Y, Takahashi M, Tsuboi Y, Yamamoto T, Yamada T. Localization and expression of cdc2 and cdk4 in Alzheimer brain tissue. Dementia Geriatr Cogn Dis. 1999;10:192–198. doi: 10.1159/000017119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jordan-Sciutto KL, Wang G, Murphy-Corb M, Wiley CA. Induction of cell-cycle regulators in simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:497–507. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64561-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ranganathan S, Scudiere S, Bowser R. Hyperphosphorylation of the retinoblastoma gene product and altered subcellular distribution of E2F-1 during Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Alzheimer Dis. 2001;3:377–385. doi: 10.3233/jad-2001-3403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayashi T, Sakai K, Sasaki C, Zhang WR, Abe K. Phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein in rat brain after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2000;26:390–397. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2000.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katchanov J, Harms C, Gertz K, et al. Mild cerebral ischemia induces loss of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors and cell cycle machinery before delayed neuronal cell death. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5045–5053. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05045.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vincent I, Jicha G, Rosado M, Dickson DW. Aberrant expression of mitotic Cdc2/cyclin B1 kinase in degenerating neurons in Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3588–3598. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03588.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Y, Geldmacher DS, Herrup K. DNA replication precedes neu-ronal cell death in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2661–2668. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02661.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harbour JW, Luo RX, DeiSanti A, Postigo AA, Dean DC. Cdk phosphorylation triggers sequential intramolecular interactions that progressively block Rb functions as cells mover through G1. Cell. 1999;98:859–869. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McShea A, Wahl AF, Smith MA. Re-entry into the cell cycle: A mechanism for neurodegeneration in Alzheimer disease. Med Hy-poth. 1999;52:525–527. doi: 10.1054/mehy.1997.0680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.LaBaer J, Garrett MD, Stevenson LF, et al. New functional activities for the p21 family of CDK inhibitors. Genes Dev. 1997;11:847–862. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng M, Olivier P, Diehl JA, et al. The p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 CDK ‘inhibitors’ are essential activators of cyclin D-dependent kinases in murine fibroblasts. EMBO J. 1999;18:1571–1583. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith MZ, Nagy Z, Esiri MM. Cell cycle-related protein expression in vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 1999;271:45–48. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00509-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ding XL, Husseman J, Tomashevski A, Nochlin D, Jin LW, Vincent I. The cell cycle cdc25A tyrosine phosphatase is activated in degenerating postmitotic neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1983–1990. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64837-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frederickson RCA. Astroglia in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1992;13:239–253. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(92)90036-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kitamura Y, Taniguchi T, Shimohama S. Apoptotic cell death in neurons and glial cells: Implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Japanese J Pharmacol. 1999;79:1–5. doi: 10.1254/jjp.79.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Achim CL, Wiley CA. Inflammation in AIDS and the role of the macrophage in brain pathology. Curr Opin Neurol. 1996;9:221–225. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199606000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xia MQ, Hyman BT. Chemokines/chemokine receptors in the central nervous system and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurovirol. 1999;5:32–41. doi: 10.3109/13550289909029743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jordan-Sciutto KL, Murray Fenner BA, Wiley CA, Achim CL. Response of cell cycle proteins to neurotrophic factor and chemokine stimulation in human neuroglia. Exp Neurol. 2001;167:205–214. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Herrup K, Busser JC. The induction of multiple cell cycle events precedes target-related neuronal death. Development. 1995;121:2385–2395. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de la Monte SM, Sohn YK, Wands JR. Correlates of p53- and Fas (CD95)-mediated apoptosis in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurological Sci. 1997;152:73–83. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)00131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arendt T, Holzer M, Gartner U, Bruckner MK. Aberrancies in signal transduction and cell cycle related events in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Trans, Suppl. 1998;54:147–158. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-7508-8_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhu Z, Rottkamp CA, Boux H, Takeda A, Perry GA, Smith MA. Activation of p38 kinase links tau phosphorylation, oxidative stress, and cell cycle-related events in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:880–888. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.10.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu X, Castellani RJ, Takeda A, et al. Differential activation of neuronal ERK, JNK/SAPK and p38 in Alzheimer disease: The “two hit” hypothesis. Mech Ageing Dev. 2001;123:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Copani A, Uberti D, Sortino MA, Bruno V, Nicoletti F, Memo M. Activation of cell-cycle-associated proteins in neuronal death: A mandatory or dispensable path? Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01663-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]