Abstract

The protein insulin-like growth factor II mRNA binding protein 3 (IMP-3) is an important factor for cell migration and adhesion in malignancies. Recent studies have shown a remarkable overexpression of IMP-3 in different human malignant neoplasms and also revealed it as an important prognostic marker in some tumor entities. The purpose of this study is to compare IMP-3 immunostaining in cutaneous squamous cell tumors and determine whether IMP-3 can aid in the differential diagnosis of these lesions. To our knowledge, IMP-3 expression has not been investigated in skin squamous cell proliferations thus far. Immunohi-stochemical staining for IMP-3 was performed on slides organized by samples from 67 patients, 34 with keratoacanthoma (KA) and 33 with primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (16 invasive and 17 in situ). Seventyfour percent of KAs (25/34) were negative for IMP-3 staining, while 57% of SCCs (19/33) were positive for IMP-3 staining. The percentage of IMP-3 positive cells increased significantly in the invasive SCC group (P=0.0111), and particularly in the SCC in situ group (P=0.0021) with respect to the KA group. IMP-3 intensity staining was significantly higher in invasive SCCs (P=0.0213), and particularly in SCCs in situ (P=0.008) with respect to KA. Our data show that IMP-3 expression is different in keratoacanthoma with respect to squamous cell carcinoma. IMP-3 assessment and staining pattern, together with a careful histological study, can be useful in the differential diagnosis between KA e SCC.

Key words: IGF-II mRNA-binding protein-3 (IMP-3), keratoacanthoma, squamous cell carcinoma.

Introduction

Insulin-like growth factor-II (IGF-II) messenger RNA (mRNA)-binding protein-3 (IMP-3), also known as K homology domain-containing protein overexpressed in cancer (KOC) and L523S, is a member of the IGF-II mRNA-binding protein (IMP) family, which also includes IMP-1 and IMP-2.1 IMP-3 is a 580 amino-acid protein encoded by a 4350-bp mRNA transcript produced by a gene located on chromosome 7p11.5.2 It is associated with cell proliferation and is considered an oncofetal protein due to its expression during embryogenesis and in some malignancies, including pancreatic carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma, endometrial carcinoma, germ cell neoplasms, ovarian carcinoma, extrapulmonary small-cell carcinoma, as well as high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma of the lung.3–10 Its exact role in carcinogenesis is still unclear.

IMP-3 has been shown to be a prognostic marker in renal cell carcinoma,5 colorectal carcinoma11 and gastric adenocarcinoma,12 and has been proposed as a potential therapeutic target for lung cancer.13 IMP-3 expression increases with the degree of dysplasia in the pancreatic ductal epithelium; it is related to tumor stage in pancreatic carcinoma3 and to aggressive behavior of urothelial carcinomas.14 Moreover, IMP-3 has been claimed as a diagnostic clue in cutaneous melanocytic neoplasms as it is expressed in malignant melanoma but not in benign melanocytic nevi, even when dysplastic features are present.15 Squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck, tongue and uterine cervix has been shown to express IMP-316–18 but, to the best of our knowledge, cutaneous squamous cell tumors have never been investigated.

Keratoacanthoma is an intriguing tumor, by most considered a benign neoplasm intended to involute with complete resolution within a few months. Other authors classify it as a subtype of squamous cell carcinoma. In routine practice, histologic and cytologic features of keratoacantoma and squamous cell carcinoma are often difficult to distinguish and a reliable marker to differentiate these lesions has not been found. The question has been raised as to whether keratoacanthoma is an unreliable histological diagnosis or these tumors have a latent, although rare, malignant potential. The understanding of the nature of keratoacanthoma has been controversial since its original description19 between 1950 and 1980. The consensus of the dermatology and dermatopathology community has been to classify this lesion as a benign condition, although papers describing malignant behavior in keratoacanthoma have been published.20–24

The objective of this study was to analyze immunohistochemical IMP-3 expression in keratoacanthomas and cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas to determine whether IMP-3 can aid in the differential diagnosis of these lesions.

Materials and Methods

Samples

A retrospective study was initiated to review the medical records of all patients with a diagnosis of keratoacantoma and squamous cell carcinoma between 2010 and 2011 at the Pathology Division, University of Cagliari, Italy. Through a careful clinicopathological correlation, we identified 67 squamous cell skin lesions grouped into 34 cases of keratoacanthoma and 33 of squamous cell carcinoma, 17 in situ and 16 invasive. Clinicopathological variables such as patients' age and sex, maximum diameter of lesions, growth phase of KA, ulceration, Clark level and depth of invasion of SCC were recorded.

Immunohistochemistry

Five micron paraffin sections were immunostained for IMP-3 (code M3626 monoclonal mouse anti-Human IMP-3; Dako Cytomation, Carpinteria, CA, USA). We used the Dako cytomation LSAB2 system-HRP in a Dako Autostainer (Dako Cytomation). This system is based on a technique that employs a modified labeled avidin-biotin (LAB) where a biotinylated secondary antibody forms a complex with peroxidase-coniugated streptavidin molecules. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubating (5 min) specimens with 3% hydrogen peroxide. Heatinduced antigen retrieval was adopted (20 min at 98° in Tris/EDTA pH9). Tissue sections were incubated (30 min at room temperature) with the IMP-3 antibody. Staining was completed after incubation (10 min) with AEC (3-amino-9.ethyl carbazole, substrate chromogen) and it resulted in a red-colored precipitate at the antigen site. Slides were reviewed by two pathologists (SS and LP) who were not aware of the clinical data, and evaluated for both tumor cell percentage and intensity of immunoreactivity. Cytoplasmic staining was considered positive for IMP-3 expression. The percentage of positive cells was recorded as 0=negative; 1=<5% of cells stained; 2=5–9.9% of cells stained; 3=10– 49.9% of cells stained; and 4=50–90%; and >90% of cells stained.15 Intensity was scored as 0 (negative), 1+ (weak), 2+ (moderate), and 3+ (strong),25 and evaluated by comparison with contiguous sebaceous glands (considered moderately positive).

Statistical analysis

The response variables involved in the analysis, such as the percentage of positive cells or their intensity, are of the semiquantitative type, more precisely, they are ordered polytomous categorical values. Therefore, of interest is not their value (i.e., 1, 2, etc.), but instead their frequency distribution and how it changes across different values of the predictor variables. To regress such variables over a specified set of predictors it is more appropriate to use the proportional odds model;26 basically, this is a generalization of the regression model for polytomous response variables. The P-values obtained from the proportional odds model for the regression coefficients resemble the evidence for the association between the specific regressor variable and the polytomous response one. The preselected significance is 5% (P<0.05). The proportional odds model is a rather standard model implemented in software as, for instance, R.27

Results

Clinicopathological features of squamous skin lesions

Clinical features of squamous skin lesions recruited in our study are presented in Table 1. The keratoacanthomas were from 34 subjects (22 males and 12 females) ranging from 39 to 90 years of age (mean age 69.5). The lesions consisted clinically of a firm, dome-shaped nodule ranging from 6 to 30 mm in maximum diameter with a horn-filled crater. They reached their full size with rapid growth in a period ranging from a few weeks to some months. Histologically, keratoacanthomas were symmetric exo-endophytic lesions with central horn-filled crater and overhanging epithelial lips, composed of glassy keratinocytes with intracytoplasmic glycogen and intraepithelial elastic fibers, characterized by a sharp outline between tumor and stroma, not extending to a depth below the eccrine glands. A rather pronounced mixed inflammatory infiltrate was present in the surrounding dermis, sometimes with development of eosinophilic or neutrophilic epithelial microabscesses. Keratinocytes showed variable degrees of nuclear atypia and mitotic figures, usually confined to the basal layers and more pronounced in keratoacanthomas in the early proliferative stage. Perineural or vascular invasion was not observed in any of our cases. Sixteen cases had at least partial features of regressing lesions showing flattening of the central hornfilled crater.

Table 1. Clinical data.

| N. | Max diam. (mm) | Sex | Age | Mean age | Median age | Site | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KA | 34 | 6–30 | M (22) | 39–90 y | 69.5 | 71.5 | Face (11), arm (6), hand (6),trunk (3), thigh (2), |

| F (12) | scalp (2), leg (2), neck (1), shoulder (1) | ||||||

| SCC invasive | 16 | 6–22 | M (11) | 63–94 y | 78,0 | 77 | Face (9), scalp (4), arm (1), ear (1), hand (1) |

| F (5) | |||||||

| SCC in situ | 17 | 3–25 | M (9) | 50–84 y | 74,4 | 77 | Face (6), leg (5), scalp (2), ear (2), hand (1), trunk (1) |

| F (8) |

KA, keratoacanthoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; M, male; F, female.

The 33 squamous cell carcinomas included 17 intraepithelial (in situ) carcinomas (Clark I) from 9 males and 8 females ranging from 54 to 84 years of age (mean age 74.4) and 16 invasive carcinomas (3: Clark II, 1: Clark III, 9: Clark IV, 3: Clark V) from 11 males and 5 females ranging from 63 to 94 years of age (mean age 78) (Tables 1 and 2). Clinically, SCCs in situ appeared as slowly enlarging erythematous patches showing little or no infiltration, with areas of scaling and crusting. Twelve of the selected invasive SCCs presented as ulcerative skin lesions with a keratinous crust and elevated, indurated surrounding, while 5 of them presented as nodular tumors often misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinomas. Histologically, irrespective of the presence or absence of ulceration, SCCs were characterized by nests of atypical squamous cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and a large, often vesicular nucleus arising from the epidermis and invading the dermis to variable extent.

Table 2. Histologic features of squamous cell carcinomas.

| Clark | I | II | III | IV | V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | 17 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 3 |

| Breslow (mm) | n.a. | 0.5–3.1 | 1 | 1.5–6.0 | 4.0–5.4 |

| Ulceration | 3 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 2 |

IMP-3 expression by immunohistochemistry

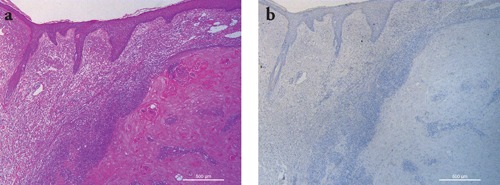

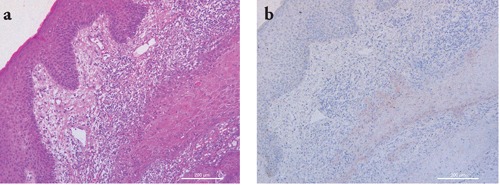

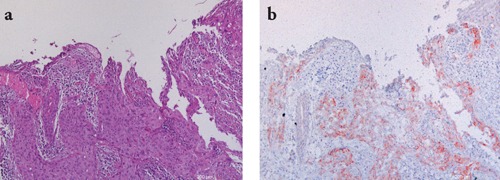

Data on IMP-3 immunohistochemical staining are presented in Table 3. Of 34 KAs, 25 (74%) were negative for IMP-3 staining (Figure 1a,b). Nine positive KAs (6 proliferative and 3 regressing) showed IMP-3 cytoplasmic expression in <50% of tumor cells. IMP-3 staining intensity was weak (1+) in six out of nine and moderate (2+) in three out of nine. The positivity was usually confined to basal layers of atypical keratinocytes (Figure 2a,b). The growth phase (proliferative or regressing) was not related to IMP-3 expression (P=0.02569). On the contrary, 19 of 33 SCCs (57%) were IMP-3 positive (8/16 invasive, 11/17 in situ) (Figure 3 a,b; Figure 4a,b). The pattern of IMP-3 expression in these cases was variable, ranging from focal and weak to intense and diffuse positivity. Fourteen of thirty-three SCCs (43%) (8/16 invasive, 6/17 in situ) were completely negative for IMP-3 (Figure 5a,b). The percentage of IMP3-positive cells in invasive SCCs was not related to the three clinicopathological features considered: ulceration (P=0.7152), Clark level (P=0.6924) and depth of invasion (P=0.8695). Age, sex, and lesion diameter were not related to IMP-3 in any of the groups. To compare immunohistochemical data on KA to SCC, we found statistical evidence for the percentage of IMP-3 positive cells to increase significantly in the invasive SCC group (P=0.0111), and particularly in the SCC in situ group (P=0.0021) with respect to the KA group. IMP-3 intensity staining increased significantly in invasive SCCs (P=0.0213), and particularly in SCCs in situ (P=0.008) with respect to KA. The intensity was not significantly related to the percentage of IMP-3 positive cells.

Table 3. Immunohistochemical data.

| N | Percentage of positive cells | Intensity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | <5% | 5–9.9% | 10–49.9% | 50–90% | >90% | weak | moderate | strong | ||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | ||

| KA | 34 | 25 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| SCC invasive | 16 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 3 |

| SCC in situ | 17 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 2 |

KA, keratoacanthoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

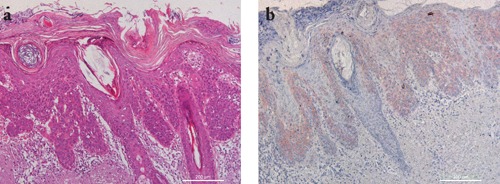

Figure 1.

Representative staining results in a case of keratoacanthoma. a) H&E staining showing a squamous cell proliferation with overhanging epithelial lips and numerous glassy keratinocytes; b) IMP-3 immunohistochemistry was negative. Scale bars: 500 µm.

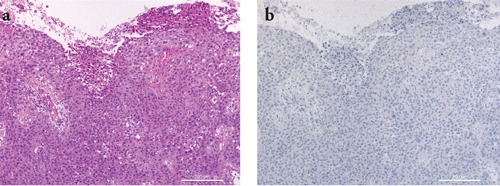

Figure 2.

Representative staining results in a case of keratoacanthoma. a) H&E staining showing a squamous cell proliferation composed of glassy keratinocytes surrounded by a prominent mixed inflammatory infiltrate; b) IMP-3 staining shows weak and focal positivity confined to basal atypical keratinocytes. Scale bars: 200 µm.

Figure 3.

Representative staining results in a case of invasive squamous cell carcinoma. a) H&E staining showing a squamous cell ulcerated tumor composed of nests of atypical epithelial cells extending into the dermis; b) IMP-3 staining shows moderate to intense diffuse positivity. Scale bars: 200 µm.

Figure 4.

Representative staining results in a case of squamous cell carcinoma in situ. a) H&E staining showing a intraepidermic squamous cell proliferation; b) IMP-3 staining shows intense and diffuse positivity. Scale bars: 200 µm.

Figure 5.

Representative staining results in a case of squamous cell carcinoma. a) H&E staining showing a squamous cell ulcerated tumor composed of nests of atypical epithelial cells extending into the dermis; b) IMP-3 staining was negative. Scale bars: 200 µm.

Discussion

Keratoacanthoma is a controversial lesion considered either benign or a subtype of squamous cell carcinoma.19 In routine histopathological examination there are tumors that are difficult to classify as either KA or SCC.

Helpful criteria for the diagnosis of a KA include epithelial lips, a sharp outline between tumor and stroma and absence of ulceration.28–33 Criteria more commonly seen in SCCs include a high mitotic index and marked cellular pleomorphism. 34 Cribier et al. found that 81% of KAs and 86% of SCCs could be diagnosed using common criteria; the remainder often showed conflicting features, such as a generally crateriform architecture with prominent nuclear atypia at the borders of the tumor.34 Many criteria commonly used for the differential diagnosis of SCC and KA are unreliable.35

In this challenging diagnostic scenario, many studies have been performed to identify immunohistochemical and molecular markers that might distinguish KAs from SCCs. Nonetheless, no marker has yet been found to differentiate KAs and SCCs with high sensitivity and specificity.

Immunohistochemical studies showed filaggrin, syndecan-1, E-cadherin, TGF-alpha, VCAM (CD-106) and ICAM (CD-54) to be more expressed in KA36–42 while a stronger expression of β-Catenin, bcl-2, p53 and Ki-67 has been found in SCC.39,43–47 Studies on flow cytometry (DNA index and proliferative index) and DNA image cytometry,48,49 as well as immunohistochemical expression of cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases, oncostatin M, β-2-microglobulin and p16 did not show statistical differences between KAs and SCCs.50–53

In our study, we observed that IMP-3 is not homogenously expressed in any group of lesions studied, although 73% of KAs were IMP-3 negative and 57% of SCCs were positive. The percentage of positive squamous cell carcinomas reflects data reported in the literature on SCC of head and neck16 (61%) and tongue17 (77%), supporting the hypothesis of IMP-3 involvement in malignancies. IMP-3 expression in SCC of the oral cavity has been shown to correlate to tumor stage, nodal stage and overall survival. Among positive cases, we observed a great variability in terms of percentage of positive cells and staining intensity that was unrelated to diameter of the lesion, ulceration, Clark level or depth of invasion. Our study did not include long-term follow-up data. Consequently we could not associate IMP-3 expression with a less favorable clinical outcome.

IMP-3 in KA has never been studied. Our finding of 73% of negative cases strongly contrasts with SCC data. If we assume that IMP-3 has a role in carcinogenesis, this would suggest the benign nature of KA. Weedon et al. recently showed that SCC transformation may occur in KA in up to 5.7% of cases, rising to 13.9% in the elderly (patients older than 90 years).54 We may hypothesize that basal IMP-3 expression at the tumor-stroma interface could indicate a potential different biological behavior in these tumors, at least in cases showing a continuous and stronger positivity. Complete excision of the lesion, in the absence of longterm follow-up, limits the understanding of the meaning of these preliminary data.

Questions about the classification and nature of keratoacanthoma still have to be answered. Given these findings, in our opinion IMP-3 expression may be useful in distinguishing KA from SCC, but it is not a specific discriminator in cases with overlapping features. Further studies in broader series or combining multiple markers are needed to better understand the role of IMP-3 in skin squamous cell tumors.

Acknowledgments:

the authors would like to thank the Banco di Sardegna Foundation, Sassari, Italy, for financial support.

References

- 1.Nielsen J, Christiansen J, Lykke-Andersen J, Johnsen AH, Wewer UM, Nielsen FC. A family of insulin-like growth factor II mRNA-binding proteins represses translation in late development. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1262–70. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Müeller-Pillasch F, Lacher U, Wallrapp C, Micha A, Zimmerhackl F, Hameister H, et al. Cloning of a gene highly overexpressed in cancer coding for a novel KH-domain containing protein. Oncogene. 1997;14:2729–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yantiss RK, Woda BA, Fanger GR, Kalos M, Whalen GF, Tada H, et al. KOC (K homology domain containing protein overexpressed in cancer): a novel molecular marker that distinguishes between benign and malignant lesions of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:188–95. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000149688.98333.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wachter DL, Schlabrakowski A, Hoegel J, Kristiansen G, Hartmann A, Riener MO. Diagnostic value of immunohistochemical IMP3 expression in core needle biopsies of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:873–7. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182189223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang Z, Chu PG, Woda BA, Rock KL, Liu Q, Hsieh CC, et al. Analysis of RNA-binding protein IMP3 to predict metastasis and prognosis of renal-cell carcinoma: a retrospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:556–64. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70732-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Herrmann FR, Rai H, Tchabo N, Lele S, Izevbaye I, et al. IMP3 distinguishes uterine serous carcinoma from endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;133:899–908. doi: 10.1309/AJCPQDQXJ4FNRFQB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammer NA, Hansen TO, Byskov AG, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Grøndahl ML, Bredkjaer HE, et al. Expression of IGF-II mRNA-binding proteins (IMPs) in gonads and testicular cancer. Reproduction. 2005;130:203–12. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu L, Shigemasa K, Ohama K. Increased expression of IGF II mRNA-binding protein 1 mRNA is associated with an advanced clinical stage and poor prognosis in patients with ovarian cancer. Int J Oncol. 2004;24:671–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon R, Bourne PA, Yang Q, Spaulding BO, di Sant'Agnese PA, Wang HL, et al. Extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas express K homology domain containing protein overexpressed in cancer, but carcinoid tumors do not. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:1178–83. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu H, Bourne PA, Spaulding BO, Wang HL. High-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas of the lung express K homology domain containing protein overexpressed in cancer but carcinoid tumors do not. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:555–63. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lochhead P, Imamura Y, Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M, Liao X, et al. Insulin-like growth factor 2 messenger RNA binding protein 3 (IGF2BP3) is a marker of unfavourable prognosis in colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:3405–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang L, Li HG, Xia ZS, Lü J, Peng TS. IMP3 is a novel biomarker to predict metastasis and prognosis of gastric adenocarcinoma: a retrospective study. Chin Med J. 2010;123:3554–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang T, Fan L, Watanabe Y, McNeill PD, Moulton GG, Bangur C, et al. L523S, an RNA-binding protein as a potential therapeutic target for lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:887–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozdemir NO, Türk NS, Düzcan E. IMP3 Expression in urothelial carcinomas of the urinary bladder. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2011;27:31–7. doi: 10.5146/tjpath.2010.01044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pryor JG, Bourne PA, Yang Q, Spaulding BO, Scott GA, Xu H. IMP-3 is a novel progression marker in malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:431–7. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3801016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clauditz TS, Wang CJ, Gontarewicz A, Blessmann M, Tennstedt P, Borgmann K, et al. Expression of insulin-like growth factor II mRNA-binding protein 3 in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. J Oral Pathol Med. 2012;29:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2012.01178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li HG, Han JJ, Huang ZQ, Wang L, Chen WL, Shen XM. IMP3 is a novel biomarker to predict metastasis and prognosis of tongue squamous cell carcinoma. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:2022–5. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182319750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu D, Yang X, Jiang NY, Woda BA, Liu Q, Dresser K, et al. IMP3, a new biomarker to predict progression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia into invasive cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1638–45. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31823272d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mandrell JC, Santa Cruz D. Keratoacanthoma: hyperplasia, benign neoplasm, or a type of squamous cell carcinoma? Semin Diagn Pathol. 2009;26:150–63. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rook A, Whimster I. Keratoacanthoma- a thirty year retrospect. Br J Dermatol. 1979;100:41–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1979.tb03568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hodak E, Jones RE, Ackerman AB. Solitary keratoacanthoma is a squamous-cell carcinoma: three examples with metastases. Am J Dermatopathol. 1993;15:332–42. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199308000-00007. discussion 343–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alyahya GA, Heegaard S, Prause JU. Malignant changes in a giant orbital keratoacanthoma developing over 25 years. Acta Opthalmol Scand. 2000;78:223–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2000.078002223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gross DA. Metastasizing keratoacanthoma? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;63:258–9. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197902000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grossniklaus HE, Wojno TH, Yanoff M, Font RL. Invasive keratoacanthoma of the eyelid and ocular adnexa. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:937–41. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30583-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pilloni L, Bianco P, Difelice E, Cabras S, Castellanos ME, Atzori L, et al. The usefulness of c-Kit in the immunohistochemical assessment of melanocytic lesions. Eur J Histochem. 2011;55:e20–e20. doi: 10.4081/ejh.2011.e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCullagh P, Nelder JA. 2nd ed. London, UK: Chapman & Hall; 1989. Generalized Linear Models. [Google Scholar]

- 27.R Development Core Team. A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2011. Available from: http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chalet MD, Connors RC, Ackerman AB. Squamous cell carcinoma vs. keratoacanthoma: criteria for histologic differentiation. J Dermatol Surg. 1975;1:16–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1975.tb00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King DF, Barr RJ. Intraepithelial elastic fibers and intracytoplasmic glycogen: diagnostic aids in differentiating keratoacanthoma from squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1980;7:140–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1980.tb01192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skirpan P, Haserick JR. Keratoacanthoma; histopathologic criteria for diagnosis. Cleve Clin Q. 1954;21:153–7. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.21.3.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weedon D. Skin pathology. 2nd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lapins NA, Helwig EB. Perineural invasion by keratoacanthoma. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:791–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Calonje E, Jones EW. Intravascular spread of keratoacanthoma. An alarming but benign phenomenon. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:414–7. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199210000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cribier B, Asch P, Grosshans E. Differentiating squamous cell carcinoma from keratoacanthoma using histopathological criteria. Is it possible? A study of 296 cases. Dermatology. 1999;199:208–12. doi: 10.1159/000018276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kern WH, McCray MK. The histopathologic differentiation of keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1980;7:318–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1980.tb01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klein-Szanto AJ, Barr RJ, Reiners JJ, Jr, Mamrack MD. Filaggrin distribution in keratoacanthomas and squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1984;108:888–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ito Y, Kurokawa I, Nishimura K, Hakamada A, Isoda K, Yamanaka K, et al. Keratin and filaggrin expression in keratoacanthoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:353–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mukunyadzi P, Sanderson RD, Fan CY, Smoller BR. The level of syndecan-1 expression is a distinguishing feature in behavior between keratoacanthoma and invasive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:45–9. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Papadavid E, Pignatelli M, Zakynthinos S, Krausz T, Chu AC. The potential role of abnormal E-cadherin and alpha-, beta- and gamma-catenin immunoreactivity in the determination of the biological behaviour of keratoacanthoma. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:582–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ho T, Horn T, Finzi E. Transforming growth factor alpha expression helps to distinguish keratoacanthomas from squamous cell carcinomas. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1167–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Melendez ND, Smoller BR, Morgan M. VCAM (CD-106) and ICAM (CD-54) adhesion molecules distinguish keratoacanthomas from cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:8–13. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000043520.74056.CD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slater M, Barden JA. Differentiating keratoacanthoma from squamous cell carcinoma by the use of apoptotic and cell adhesion markers. Histopathology. 2005;47:170–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tataroglu C, Karabacak T, Apa DD. Betacatenin and CD44 expression in keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Tumori. 2007;93:284–9. doi: 10.1177/030089160709300310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sleater JP, Beers BB, Stephens CA, Hendricks JB. Keratoacanthoma: a deficient squamous cell carcinoma? Study of bcl-2 expression. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:514–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1994.tb00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Batinac T, Zamolo G, Coklo M, Hadzisejdic I, Stemberger C, Zauhar G. Expression of cell cycle and apoptosis regulatory proteins in keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2006;202:599–607. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Biesterfeld S, Josef J. Differential diagnosis of keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the epidermis by MIB-1 immunohistometry. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:3019–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Basta-Juzbasi A, Klenkar S, Jaki - Razumovi J, Pasi A, Loncari D. Cytokeratin 10 and Ki-67 nuclear marker expression in keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2004;12:251–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Randall MB, Geisinger KR, Kute TE, Buss DH, Prichard RW. DNA content and proliferative index in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;93:259–62. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/93.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herzberg AJ, Kerns BJ, Pollack SV, Kinney RB. DNA image cytometry of keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;97:495–500. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12481529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tran TA, Ross JS, Boehm JR, Carlson JA. Comparison of mitotic cyclins and cyclindependent kinase expression in keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:391–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1999.tb01863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tran TA, Ross JS, Sheehan C, Carlson JA. Comparison of oncostatin M expression in keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:427–32. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Graham RM, MacFarlane AW, Curley RK, Nash JR. Beta 2 microglobulin expression in keratoacanthomas and squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 1987;117:441–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1987.tb04923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaabipour E, Haupt HM, Stern JB, Kanetsky PA, Podolski VF, Martin AM. p16 expression in keratoacanthomas and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin: an immunohistochemical study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:69–73. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-69-PEIKAS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weedon DD, Malo J, Brooks D, Williamson R. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in keratoacanthoma: a neglected phenomenon in the elderly. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:423–6. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181c4340a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]