Abstract

Chromatin remodeling is fundamental for B cell differentiation. Here, we explored the role in this process of KAP1, the cofactor of KRAB-ZFP transcriptional repressors. B lymphoid-specific Kap1 knockout mice displayed reduced numbers of mature B cells, lower steady-state levels of antibodies and accelerated rates of decay of neutralizing antibodies following viral immunization. Transcriptome analyses of Kap1-deleted B splenocytes revealed an upregulation of PTEN, the enzymatic counter-actor of PIK3 signaling, and of genes encoding DNA damage response factors, cell-cycle regulators and chemokine receptors. ChIP/seq studies established that KAP1 bound at or close to a number of these genes, and controlled chromatin status at their promoters. Genome-wide, KAP1-binding sites avoided active B cell-specific enhancers and were enriched in repressive histone marks, further supporting a role for this molecule in gene silencing in vivo. Likely responsible for tethering KAP1 to at least some of these targets, a discrete subset of KRAB-ZFPs is enriched in B lymphocytes. This work thus reveals the role of KRAB/KAP1-mediated epigenetic regulation in B cell development and homeostasis.

Keywords: B cells, epigenetics, gene expression, KAP1, KRAB-ZFP

INTRODUCTION

Epigenetics plays a major role in ontogeny and cell specification, as illustrated by human developmental diseases caused by mutations in components of the epigenetic machinery, and by the phenotypic consequences of the knockout of epigenetic regulators on mouse embryogenesis and stem cell biology1. This level of regulation is also key to the lineage differentiation of adult tissues, in particular for the development of immune cells. As a corollary, altered epigenetic regulation has been linked to autoimmune and allergic diseases as well as to hematopoietic malignancies2

B cell progenitors (Pro-B cells) derive from multipotent lymphoid progenitors in the bone marrow (BM). Pro-B cells initiate the immunoglobulin (Ig) heavy (IGH) μ chain locus rearrangement, completed during maturation to B precursor (Pre-B) cells. After rearrangement of an Ig light (IGL) chain locus and surface expression of a complete IgM molecule, immature B cells egress from the bone marrow and migrate to the spleen. There, they undergo further maturation steps called transitional stages 1 and 2 (T1 and T2), and eventually differentiate into mature follicular (FO) and marginal zone (MZ) B cells3,4. FO cells are mostly constituted of conventional B2 cells, which can recirculate and are responsible for T-dependent antibody production. By contrast, MZ B lymphocytes are sessile non-conventional cells that, together with B1 cells, contribute to T-independent antibody response. B1 cells predominantly reside in the peritoneal and pleural cavities and are thought to arise from a self-renewing fetal precursor located in the peritoneum, or from B1 progenitors in adult BM4.

B cell development and homeostasis require the integration of external and internal clues. External stimuli are sensed mainly by the B cell (BCR) and other membrane receptors (i.e. IL7R, Notch2, BAFFR and various chemokine receptors). Signals from these receptors are then conveyed notably through the PLCγ, Ras, STAT, and PI3K pathways, and are integrated within a network of transcription factors including E2A, EBF1 and Pax5 at early stages of B cell development, and NF-kB and Aiolos in mature peripheral B cells3,5. Recent studies have revealed that the target accessibility of these cell fate-determining transcription factors is strictly controlled by chromatin modifiers, which induce the relaxation or the compaction of chromatin at these loci. Additionally, chromatin remodeling is involved in regulating BCR locus rearrangement, class switch recombination (CSR) and somatic hypermutation, all of which are key steps in B cell development and function6.

Krüppel-associated box zinc finger proteins (KRAB-ZFPs) constitute a vast family of tetrapod-specific transcription repressors, which underwent a marked expansion by gene and segment duplication during evolution7,8. KRAB-ZFPs are characterized by the presence at their C-terminus of tandem repeats of C2H2 zinc fingers, which confer them with the ability to bind specific polynucleotidic sequences, and at their N-terminus of one or two KRAB domains responsible for interacting with KRAB-associated protein 1 (KAP1)9. KAP1, also known as TRIM28 or TIF1β, is a ubiquitously expressed member of the tripartite motif-containing (TRIM) family. It recruits chromatin modifiers including the SETDB1 histone methyltransferase, the CHD3/Mi2 component of the NuRD complex and Heterochromatin Protein 1 (HP1), thus inducing heterochromatin formation by histone 3 tri-methylation on lysine 9 (H3K9me3) and histone deacetylation10-12. This rather advanced characterization of the biochemical mechanism of KRAB-ZFP/KAP1 action contrasts with the paucity of information on the physiological roles of this system. Nevertheless, it has been found that KAP1 is essential for early embryonic development, as it partakes during this period in the pluripotent self-renewal of embryonic stem cells, the repression of endogenous and some exogenous retroviruses and, together with the KRAB-ZFP ZFP57, in the maintenance of imprinting marks. In addition, KAP1 and/or specific KRAB-ZFPs have been demonstrated to play roles in tumorigenesis, the control of behavioral stress and Parkinson disease13-20.

In the present work, we used a conditional knockout approach to investigate the impact of KRAB/KAP1-mediated regulation on B cell development. B cell specific Kap1-deleted mice exhibited a significant defect in B cell differentiation and long-term antibody production. Through a combination of microarrays and ChIP-sequencing, we identified a number of KAP1 target genes, amongst which Pten, the dysregulation of which likely played an important role in the observed phenotype. Genome-wide, we also found that KAP1 binding sites significantly correlated with regions marked by the repressive histone modification H3K9me3, and in contrast avoided B cell-specific regulatory elements bearing active marks such as H3K4me1 and H3K4me3 or bound by the PU.1 transcription factor21. Finally, we identified a subset of KRAB-ZFPs enriched in B lymphocytes, likely responsible for recruiting KAP1 to some of its genomic targets. Taken together our data reveal the importance of KRAB/KAP1-mediated epigenetic regulation for B cell differentiation and homeostasis.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were approved by the local veterinary office and carried out in accordance with the European Community Council Directive (86/609/EEC) for care and use of laboratory animals.

Mice

Generation and genotyping of mice with a floxable KAP1 allele (KAP1flox; Tif1βL3/L3), the CD19-Cre and the cre-reporter stopfloxYFP mouse strains have been described previously 13,22,23. CD19-Cre/KAP1flox and CD19-Cre/KAP1flox/stopfloxYFP mice were generated in a mix C57/bl6-129sv background, or C57/bl6 where specified. The offspring resulting from all the generated strains was born at expected rate. For bone marrow chimera see supplemental Methods.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

At the moment of sacrifice, we harvested spleen, bone marrow by flushing femur(s), and PEC by intra-peritoneum wash. For antibodies used see supplemental Methods. Cells were analyzed by Dako CyAn ADP cytometer (Beckman-Coulter) or sorted by FACSAria II (Becton-Dickinson). About 300000 events falling in the physical parameters gate were acquired. See text and supplemental Methods for staining strategies.

Small scale DNA, RNA and protein analysis

Single cell suspensions from spleen or thymus, either total or sorted by flow cytometry where indicated, were pelleted and DNA was isolated by DNeasy kit purification (Qiagen), RNA by RNeasy plus kit purification (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed by Superscript II (Qiagen), and protein obtained after lysis with RIPA buffer. For detailed protocols see supplemental Methods. All the primers used in this work were designed by Primer Express software (Applied biosystem) or GetPrime resource (http://updepla1srv1.epfl.ch/getprime) (Gubelmann et al., Database, in press) and are listed in supplemental Methods. Specificity of all primer pairs was confirmed by dissociation curve analysis and efficiency by performing reactions with serially diluted samples. All microarray data are available on the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession number GSE34446.

In vitro assays and immunizations

See supplemental methods.

High throughput analyses

See supplemental Methods.

Statistical analysis

We used non parametric tests for experiment with n<100. We used Mann-Whitney test for comparisons between two groups, Kruskal-Wallis and two-ways ANOVA tests for comparisons among more than two groups, Spearman correlation test for correlation analyses and modified Fischer’s exact test as contingency test. Unless specified, two-tailed tests were used. For statistical analysis of high throughput data see related paragraphs.

RESULTS

KAP1 controls B lymphoid differentiation

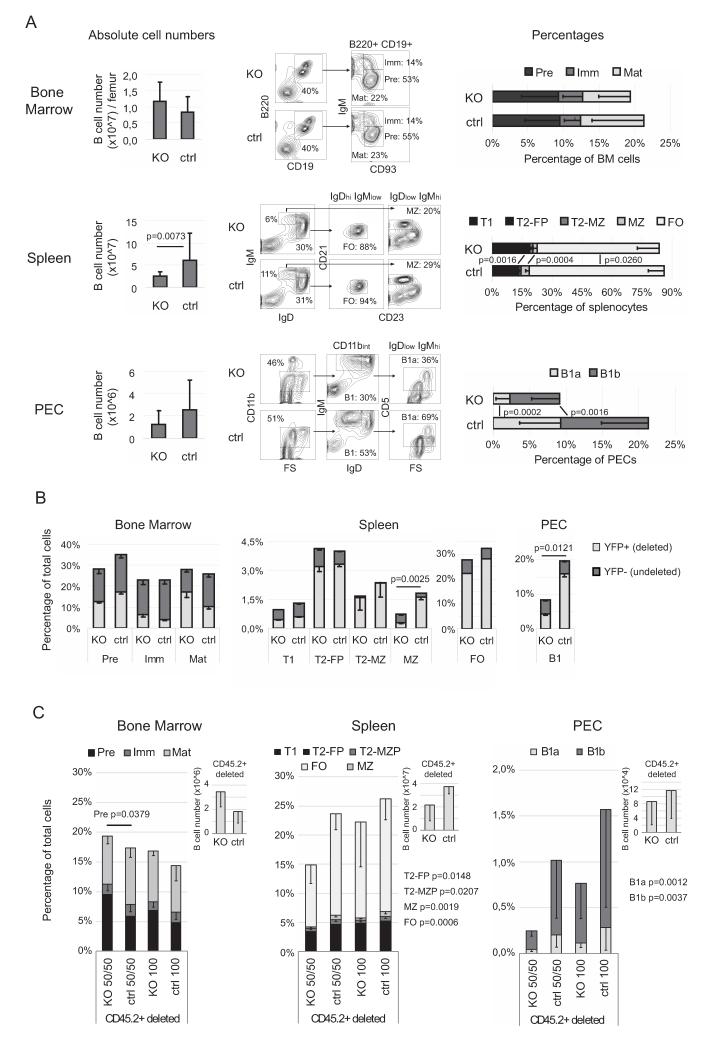

In order to evaluate KRAB-ZFP/KAP1 role in B lymphoid development and function, we crossed Kap1flox (Tif1βL3/L3) 13 in mixed C57/bl6-129sv background with the C57/bl6 heterozygous CD19-Cre mouse strain, in which the recombinase is expressed at the pro-B stage 22. CD19-Cre/Kap1flox deficient mice were born at the expected Mendelian ratio and appeared normal and healthy. PCR-based genomic DNA analyses of CD19pos and CD19neg cells confirmed that, as expected, Kap1 was deleted only in the CD19pos subset. Nevertheless, the efficiency of depletion did not reach 100% and some residual KAP1 mRNA and protein could be detected in B-enriched splenocytes (Fig. S1A). Hematoxylin-eosin staining of BM, spleen and peripheral lymph nodes revealed normal histological features in B lymphoid Kap1-deleted mice (data not shown). We next performed flow cytometry analyses (Fig. 1A). We did not observe significant differences in the frequency of precursor (Pre; CD93posIgMneg), immature (Imm; CD93posIgMpos) and mature (Mat; CD93negIgMpos) B cells, nor in the number of total B cells in the bone marrow of CD19-Cre/Kap1flox deficient compared to littermate wt/Kap1flox control mice. However, the analysis of peripheral B cells revealed a significant decrease in mature follicular (FO; IgMlowIgDhiCD21intCD23pos) and marginal zone (MZ; IgMhiIgDlowCD21hiCD23neg) B cells and an expansion of transitional stage 2 follicular progenitor (T2-FP; IgMhiIgDhiCD21int CD23pos) B cells in the absence of KAP1. Transitional MZ progenitor (T2-MZ; IgMhiIgDhiCD21hiCD23pos) and transitional stage 1 (T1; IgMhiIgDlow CD21low-neg CD23neg) cells were unaffected. Consistent with the observed reduced frequency of mature B cells, Kap1-deleted mice harbored significantly fewer B splenocytes than control littermates. Moreover, peritoneal exsudate cells (PEC) from knockout animals comprised a significantly reduced fraction of both B1a (CD11bposIgMhiIgDlowCD5pos) and B1b (CD11bposIgMhiIgDlowCD5neg) cells. Because a slight decrease in MZ and B1 cells has been linked to the reduced expression of the CD19 gene in which Cre is knocked in 24, we also performed flow cytometry analysis on C57/bl6 CD19-Cre/Kap1flox deficient mice. It confirmed that these animals exhibited a reduction in mature conventional and non-conventional B cells when compared to their C57/bl6 CD19-Cre/KAP1wt counterparts, ascertaining that the observed phenotype was truly due to KAP1 deletion and not to CD19 hemizygosity (Fig. S1B).

Figure 1. KAP1 deficient mice display reduced numbers of mature B cells.

A) Bone Marrow (top), spleen (middle) and PE (bottom) cells from 8-12 wks-old CD19-Cre/KAP1flox (KO) and littermate wt/KAP1flox control mice (ctrl) were counted and analyzed by flow cytometry. Left panels, total number of B cells; middle panels, representative flow cytometry analysis; right panels, average and SD of the percentage of the indicated populations, n≥ 15. B) CD19-Cre/YFPflox/KAP1flox (KO) and CD19-Cre/YFPflox/KAP1floxhet (ctrl) mice analyzed by flow cytometry as in A). Percentages of YFP-positive and negative cells in the depicted populations are given as average and SEM. n=5. C) Chimeric mice obtained by transplant of 50% CD45.2+ CD19-Cre/YFPflox/KAP1flox + 50% CD45.1+ wild-type (KO 50/50; n=8), 50% CD45.2+ CD19-Cre/YFPflox/KAP1wt + 50% CD45.1+ wild-type (ctrl 50/50; n=8), 100% CD45.2+ CD19-Cre/YFP-flox/KAP1flox (KO 100; n=3) and 100% CD45.2+ CD19-Cre/YFPflox/KAP1wt (ctrl 100; n=4) lin− cells were analyzed by flow cytometry 6-10 weeks after injection. Only CD45.2+ deleted (YFP-positive) cell frequencies are shown. For CD45.2− non-deleted (YFP-negative) frequencies see Fig. S1. Subpopulations were analyzed as in A). Average and SD are shown. p values for the indicated populations comparing KO50/50 vs. ctrl 50/50.

p values by Mann-Whitney test. Pre: Pre-B cell progenitors; Imm: Immature B cell progenitors; Mat: Mature B cell progenitors. T1: transitional 1 progenitors; T2-FP: transitional 2 follicular progenitors; T2-MZP: transitional 2 marginal zone progenitors; FO: follicular B cells; MZ: marginal zone B cells. See also Fig. S1.

Since Kap1 deletion in total CD19pos cells was not complete (Fig. S1A), we asked if Kap1-excised cells were equally represented at all differentiation stages. We sorted T1, T2-FP, T2-MZ, FO and MZ cell populations from the spleen of mutant mice and analyzed their genomic DNA by semi-quantitative PCR. We found that all the populations were efficiently excised (about 90%) except for the MZ (where excision efficiency was less than 60%), indicating a selective disadvantage of the KAP1-deficient cells in this subpopulation (Fig. S1C). These data were further supported by the analysis of the mouse strain generated by breeding Kap1-deleted mice with stopfloxYFP animals, where Cre induction results in YFP expression23. After verifying that there was a direct correlation between Kap1 excision and YFP-mediated fluorescence (Fig. S1D), we compared the frequency of YFPpos cells in the different B cell subpopulations in KAP1-deficient and -competent mice. The results not only confirmed that B lymphoid Kap1 knockout mice harbored a reduced frequency of spleen MZ and FO and of B1 cells in PEC, but also that Kap1-deleted cells were significantly underrepresented amongst spleen MZ and B1 cells (Fig. 1B). Together, these data indicated that KAP1 is required for the efficient production and/or maintenance of a mature B cell compartment.

To consolidate our findings, we generated bone marrow chimeric mice by transplanting CD45.2pos BM-derived lineage-depleted hematopoietic progenitors (linneg HPC) purified from CD19-Cre/Kap1flox/stopfloxYFP deficient or CD19-Cre/Kap1wt/stopfloxYFP control donor mice (mixed or not in equal proportion with CD45.1pos wild type linneg HPC) in CD45.1pos mice. Flow cytometric analysis at 6-10 weeks post-reconstitution (Fig. 1C) revealed an exacerbation of the phenotype observed in the non-chimeric deficient mice, with a significant decrease in the frequency of Kap1-deleted CD45.2pos T2-FP, T2-MZ, MZ, and FO cells in the spleen, as well as B1a and B1b cells in the PEC (although reconstitution from donor-derived cells was minimal in this latter compartment, as expected). Furthermore, we observed an accumulation of Kap1-deleted CD45.2pos pre-B cells in the BM of chimeric mice engrafted by 50% deficient and 50% wild type cells (KO 50/50), when compared to controls (ctrl 50/50). The same trend was observed in the CD45.2pos deleted cells in chimeric mice engrafted by 100% deficient (KO 100) cells, but not in the CD45.2pos non-deleted cells, when compared to the respective controls (Fig. 1C and S1E). Thus, early B cell differentiation was significantly affected by KAP1 removal in mice harboring chimeric bone marrow. Overall, our phenotypic analysis indicates that KAP1 regulates the early and late differentiation of both conventional and non-conventional B cells.

KAP1-deficient mice display defects in antibody production

Even though the presence of Kap1-deleted mature B cells indicated that BCR rearrangement occurred in the absence of KAP1, we verified by PCR that BCR polyclonality was not compromised in this setting. We did not observe any difference in the distribution of the rearranged bands when comparing splenocytes harvested from deficient and control mice. This indicated that KAP1 deletion did not induce a major skew in the usage of the variable Ig regions (Fig. S2A).

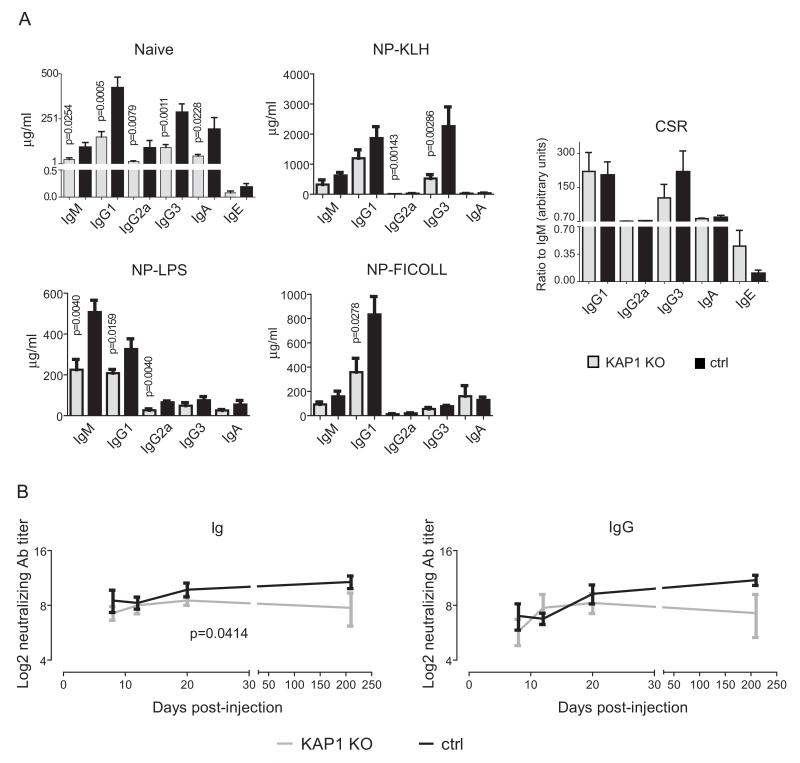

We next assessed the functionality of KAP1-deficient B cells. Serum levels of antibodies of all isotypes were significantly reduced in knockout compared to control naïve mice (Fig. 2A), suggesting a defect in steady-state antibody production. We then immunized mice by NP-KLH, NP-LPS and NP-Ficoll injections to test T-dependent, T-independent type 1 and T-independent type 2 antibody responses, respectively, and measured serum antibody titers at day 21 post-injection. Total antibody levels were lower in B lymphoid Kap1-deleted than in control mice for all isotypes and in all immunization protocols, but knockout animals could mount both T-dependent and -independent NP-specific antibody responses (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2B). Furthermore, CSR efficiently proceeded in mice immunized in the presence of aluminum adjuvant, albeit with a bias towards IgE in the absence of KAP1 (Fig. 2A). Also, B lymphoid Kap1-deleted mice produced normal levels of neutralizing antibodies early after immunization with either UV-treated VSV (not shown) or with recombinant adenoviral vector particles expressing the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) envelope glycoprotein (rAD/VSV-G). However, neutralizing antibody levels dropped significantly faster in Kap1 knockout than in control mice, indicating that KAP1 contributes to the maintenance of antibody memory (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Defective immune responses in B lymphoid KAP1 deficient mice.

A) ELISA detecting total immunoglobulin was performed on CD19-Cre/KAP1flox (KAP1 KO) and littermate wt/KAP1flox control (ctrl) mouse sera either at steady-state (upper left panel, naive) or 21 days post-immunization with indicated agents (middle and lower panels). Right panel, Class Switch Recombination (CSR) was calculated as the ratio between the amount of indicated isotype and IgM in mice injected with NP-KLH or NP-LPS and alum. Average and SEM are shown, n≥4. p values by one-tailed Mann-Whitney test. B) Serum titers of neutralizing total Ig and IgG from CD19-Cre/KAP1flox (KAP1 KO) and littermate wt/KAP1flox control (ctrl) mice injected with rAD/VSV-G. Sera were analyzed at day 8, 12, 20 and 210. Mean and SEM are shown, n=4. p value by two-ways ANOVA test. Only significant p values are depicted. See also Fig. S2.

Transcriptional dysregulation in Kap1-deleted B cells

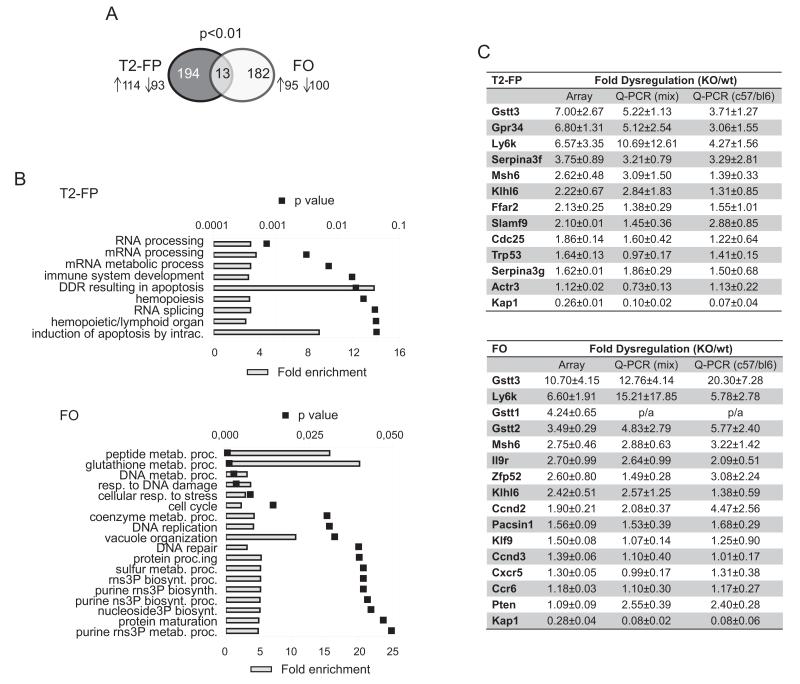

In order to identify the genes targeted by KAP1 in B cells, we performed microarray gene expression analyses on the cell populations phenotypically most affected by the deletion of this transcriptional regulator. We extracted RNA from T2-FP and FO lymphocytes purified from the spleen of CD19-Cre/Kap1flox and littermate controls and verified by Q-PCR that Kap1 depletion was about 90% in both cell populations from mutant mice (Fig. S3A). We found 207 and 195 genes, respectively, dysregulated in T2-FP and FO Kap1-deleted cells compared to controls (p<0.01), with about equal proportions of up- and down-regulated genes (Fig. 3A; for the complete list of dysregulated genes see Table S1). Functional annotation using the DAVID bioinformatics resource25,26 indicated that genes related to RNA processing/metabolic processes and immune system development were highly enriched in the list of dysregulated genes in T2-FP deficient progenitors, while in mature FO deficient cells the most represented classes were linked to metabolic processes and response to various forms of stress, including DNA damage (Fig. 3B). These data further support a role of KAP1 in both the differentiation of progenitor and the homeostasis of mature B lymphocytes.

Figure 3. Transcriptome analyses of B lymphoid KAP1 deficient splenocytes.

A) Number of genes dysregulated in T2-FP and FO Kap1-deleted cells compared to controls, arrow up=number of upregulated genes, arrow down=number of downregulated genes. B) DAVID bioinformatics database analysis of dysregulated genes. Gene Ontology biological process classes of genes enriched in the dysregulated gene lists for T2-FP (top panel) and FO (bottom panel) KAP1-deficient cells. Fold enrichment and p values are depicted. DDR=DNA damage response, intrac.=intracellular, metab.=metabolic, proc.=process, resp.=response, biosynth.=biosynthetic, rns=ribonucleoside, ns=nucleoside, 3P=triphosphate. C) Fold dysregulation of the depicted genes as assessed by Array, Q-PCR on RNA extracted from C57/bl6-129sv CD19-Cre/KAP1flox deficient and littermate wt/KAP1flox controls (Q-PCR mix) and Q-PCR on RNA extracted from C57/bl6 CD19-Cre/KAP1flox deficient and CD19-Cre/KAP1wt controls (Q-PCR C57/bl6). Average ± SD are shown; n=3. Top panel, T2-FP population; Bottom panel, FO population. p/a: present in KAP1-deleted and absent in control samples. See also Fig. S3 and Table S1.

We used Q-PCR to quantify more precisely a selected set of dysregulated transcripts in wild type and Kap1 KO mice from both mixed and C57/bl6 backgrounds (Fig. 3C). In both T2-FP and FO cells, the RNAs most highly upregulated corresponded to gluthatione S-transferases of the theta class. While it remains to be determined whether these detoxifying enzymes fulfill specific functions in lymphocytes, several of the other transcripts deregulated by KAP1 removal pertained to B cell signaling. PTEN (inositol phosphatase and tensin homolog), an enzymatic counter-regulator of the PI3K pathway, was found to be upregulated in FO cells by both Q-PCR and Western blot (Fig. 3C and S3B). Consistent with this result, levels of FoxO1, a factor negatively regulated by PI3K, were increased in Kap1-deleted cells (Fig. S3B). Similarly, levels of lymphoid-specific BTB-kelch protein KLHL6 RNA were increased in both T2-FP and FO Kap1-deleted cells, a point noteworthy considering the previously described involvement of this factor in BCR signaling and germinal center formation 27. KAP1 removal also induced an upregulation of genes encoding for some immune receptors (i.e. Ly6k, Gpr34, Slamf9, Il9r) and transcription factors (i.e. Zfp52 and Klf9), and for the mismatch-repair-mut-l-homolog-6 (Msh6) protein. Msh6 has been implicated in damage recognition, regulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis, and modulation of antibody diversification28,29. Other genes encoding proteins involved in cell cycle and apoptosis, such as CDC25B and TRP53 in T2-FP cells and cyclins D2 and D3 in FO cells, and in cytoskeleton rearrangement and cell migration, such as the chemokine receptors CXCR5 and CCR6 and the cytoskeleton remodeler PACSIN1 in FO cells and the actin-related protein ACTR3 in T2-FP, were also upregulated in Kap1 knockout cells. This links KAP1-mediated regulation with the migration and proliferation pathways in both transitional progenitors and mature B cells. Noteworthy, endogenous retroelements were not deregulated in KAP1-deficient cells (data not shown), as expected from their irreversible silencing through DNA methylation after the early embryonic period18.

KAP1 binding and chromatin modifications in B cells

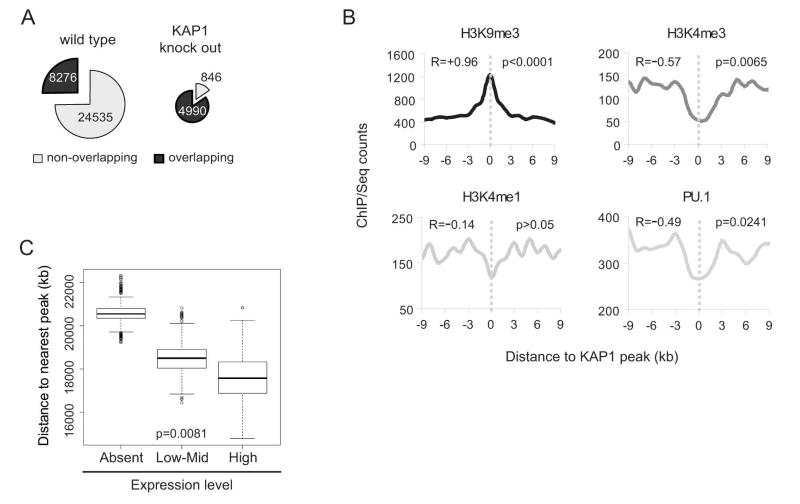

In order to discriminate between primary KAP1 targets and secondarily deregulated genes, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) studies of B-enriched splenocytes extracted from wild type and littermate Kap1-deleted mice, using an antibody that recognizes the KAP1 RBCC domain 11. We subjected the KAP1-specific immunoprecipitates to deep sequencing and, after mapping the reads, used the ChIP-Seq Analysis Server (http://ccg.vital-it.ch/chipseq/) to identify significant peaks. We obtained 32,811 discrete peaks in the wild type sample and 5,886 in its KAP1-depleted counterpart. Upon intersecting the two lists, we found that about 75% (24,535) of the wild type peaks had no overlapping peak in the Kap1-deleted sample (defined as a peak within a ±1kb window from the interrogated peak). Reciprocally, more than 80% (4,990) of the peaks mapped in the Kap1-deleted sample had an overlapping peak in the wild type, probably originating largely from the background of Kap1-undeleted cells (Fig. 4A). This strongly suggests that the majority of peaks identified in the wild type sample represent bona fide KAP1 binding sites. We performed a ChIP/Seq-mediated census of H3K9me3-bearing regions in the same two samples, as KAP1 action typically leads to the deposition of this mark in vitro10,12. We found 1784 and 1355 such regions in B-enriched splenocytes extracted from wild type and littermate Kap1-deleted mice, respectively. Amongst these, half of H3K9me3-enriched regions found in the wild type were also present in the Kap1-deleted samples, while almost two-thirds of the H3K9me3 peaks detected in the knockout sample overlapped with peaks recorded in the wild type (Fig. S4A).

Figure 4. KAP1 binding sites and chromatin modifications in B cells.

Chromatin from wild type and KAP1-deficient B splenocytes was immunoprecipitated with a KAP1- or H3K9me3-specific antibody and captured DNA was sequenced. A) KAP1 binding sites identified in wild type (left) and KAP1 deficient (KO; right) B splenocytes. Overlapping: number of wt (left) or KO (right) sites overlapping with at least 1 site identified in the KO (left) or wt (right) sample. The window set for the overlapping is ± 1kb. B) Stratification of the indicated features around KAP1 binding sites (set at 0), p values and correlation coefficient (R) by Spearman test. C) UCSC genes were sorted on the basis of expression as assessed in the microarray wild type FO samples (see table S1) and distance to the nearest KAP1-H3K9me3 peak was evaluated. Absent: genes with expression signal <30; Low-Mid: signal between 31 and 1000; Hi: signal between 1001 and 45000. Boxplots of bootstrapped values are shown. p value by Kruskal-Wallis test, Dunn post test by pairs: absent vs low-mid p<0.05, absent vs high p<0.05, low-mid vs high p>0.05. See also Fig. S4.

We then performed correlation studies to characterize better KAP1-bound genomic regions. For this, we examined the distribution around KAP1 binding sites of different histone marks and transcription factors, using datasets generated in B splenocytes by others and us21. KAP1-bound regions were significantly enriched in H3K9me3 and depleted in H3K4me3, a mark typically found at active and/or poised promoters30. Also, KAP1 peaks avoided regions bearing the H3K4me1 mark as well PU.1 binding sites, which together characterize cell-specific enhancer-like loci21 (Fig. 4B). In B splenocytes, KAP1 is thus associated with genomic loci adorned with repressive modifications, whereas it is excluded from active promoter/enhancer elements. In order to be more stringent and consider only the heterochromatin-associated role of KAP1, we zoomed onto KAP1 peaks that coincided with H3k9me3-enriched regions (<1kb distance), which represented about 30% of the total KAP1 binding sites (Fig. S4B). We first calculated the distance from all genes to the nearest KAP1/H3K9me3 peak and crossed these data with the results of our transcriptional analyses in FO cells, since these account for about 80% of total B splenocytes. Although there was a slight trend for genes upregulated in Kap1 KO cells to be closer to and downregulated genes to be farther from KAP1 peaks than average, the differences between median distances were not significant (Fig. S4C), indicating that proximity is not the only factor at play in KAP1-mediated regulation. We then correlated absolute gene expression and distance to KAP1/H3K9me3 peaks and found that expressed genes (according to our microarray data) where significantly closer to KAP1/H3K9me3 peaks than non-expressed genes (Fig. 4C). This observation might seem contradictory for a repressive molecule like KAP1. However, we think that it only indicates that KAP1 is not associated in vivo to constitutive silent chromatin but rather to regions, the expression of which needs to be finely regulated. As an alternative explanation, KAP1 might show a preference for gene-rich regions, which at least in the human genome have been demonstrated to contain most of the expressed genes31. We then mapped the closest gene to each KAP1/H3K9me3 peak and used the list of closest genes to peaks (≤20 kb) to interrogate the DAVID bioinformatics resource25,26. We found cell transcription-, RNA processing-related and cytokine response Gene Ontology biological processes classes significantly enriched, suggesting a direct KAP1-mediated regulation of these genes (Fig. S4D). Interestingly, when we looked at Simple Modular Architecture Research Tool (SMART) protein domain classes, we found the KRAB-domain class as the most enriched in the list of closest genes to KAP1/H3K9me3 peaks (Fig. S4D). This correlates the previous observation that, in some human cell lines, KAP1 binds to and, in some cases, controls expression of KRAB-ZFP genes32-35.

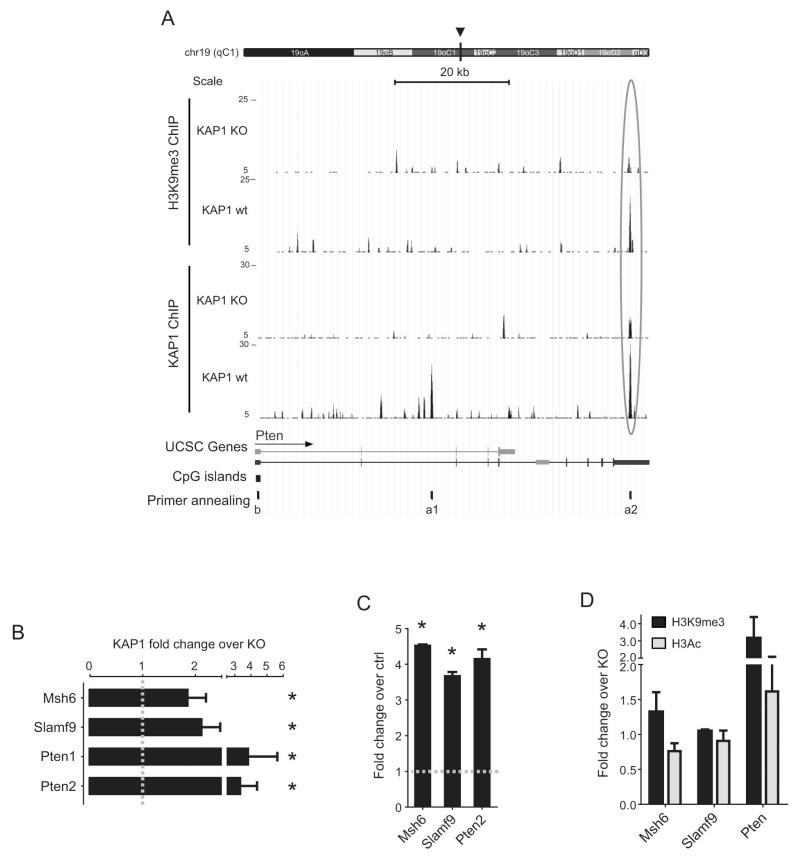

When we examined specific genes upregulated in Kap1 knockout FO or T2-FP cells (see Fig. 3), we found two KAP1 sites within the Pten gene, one in an intron and one in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR). Furthermore, we observed that the distal KAP1 Pten peak coincided with a high H3K9me3 signal in wild type cells, which strongly decreased in KO cells (Fig. 5A). KAP1 and H3K9me3 peaks were also detected near the Msh6 and Slamf9 genes (Fig. S5), ChIP/Q-PCR with specific primers confirming significant KAP1 and H3K9me3 enrichment at all these sites (Fig. 5B-C). Finally, we could detect an enrichment of H3K9me3 and a depletion of the activation mark histone 3 acetylation (H3Ac) in wild type compared with Kap1-deleted B splenocytes at the promoters of these genes (Fig. 5D). Together, these results confirm that Pten and these other genes are direct targets of KAP1.

Figure 5. KAP1-mediated control of genes dysregulated in KAP1-deficient B cells.

A) Pten genomic locus with KAP1- and H3K9me3- ChIP/seq signal for Kap1 wt and KO B splenocytes. Chromosome and relative position (arrowhead), scale, UCSC based transcripts (most abundant in black, least abundant in grey), CpG islands (suggestive of promoter regions) and position of PCR primers used for validation in B-C) (a) and D) (b) are depicted. Arrow indicates sense of transcription. B-D) Chromatin from wild-type and KO B splenocytes was immunoprecipitated with KAP1- (B), H3K9me3- (C-D, black bars) or H3Ac- (D, grey bars) specific Abs and Q-PCR was performed with primers amplifying the region depicted in A) and Fig. S4 as a for B-C) and as b for D). Enrichment of IP samples is expressed as total input fraction (Fold change over ctrl; C) normalized on the KO signal (Fold change over KO; B, D). Average of fold change in control gene (GAPDH) was set at 1 (grey line). Average + SEM are shown. n=4; * p<0.05 compared to control gene signal, one-tailed Mann-Whitney test. See also Fig. S5.

A subset of KRAB-ZFPs is differentially expressed in B lymphoid cells

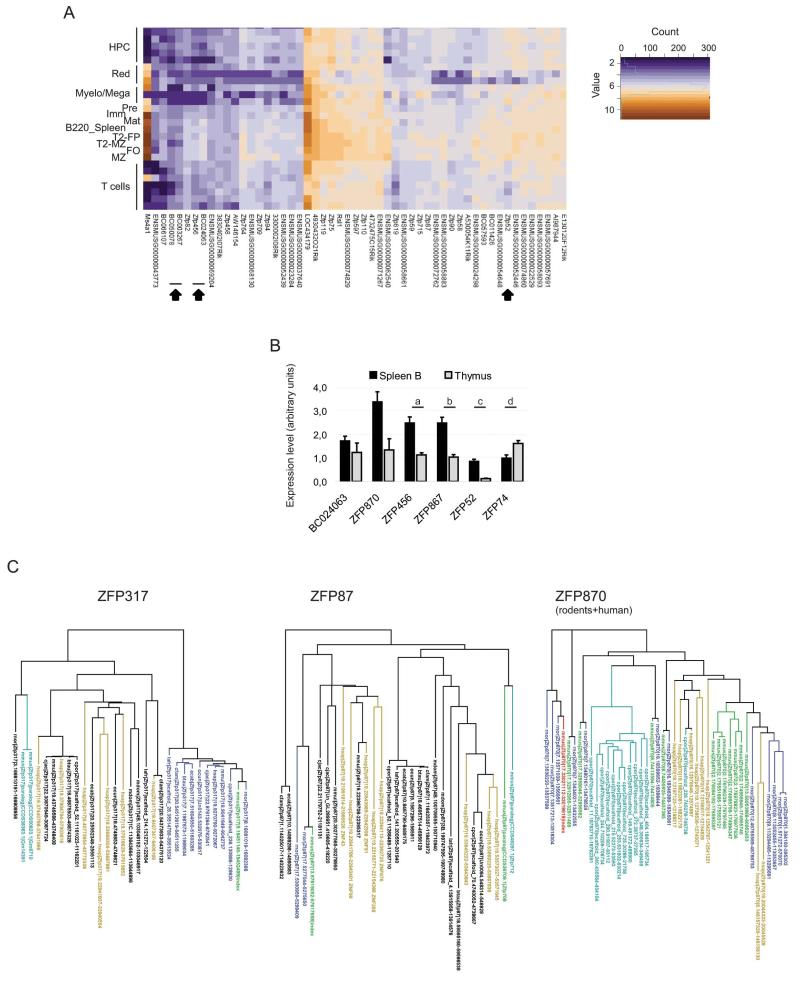

We finally determined which members of the KRAB-ZFP family are expressed in B lymphoid cells, to account for KAP1 recruitment to at least some of its genomic targets. For this, we isolated RNA from a large series of cells purified by FACS from the bone, spleen and thymus of wild type mice, representing some 26 stage/lineage-specific steps of lympho-hematopoietic differentiation. We then quantified transcripts from 304 murine KRAB-ZFPs and 25 control genes by using a custom probe-set (282 probes) for the NanoString nCounter platform36 (for a complete list of all tested hematopoietic populations and staining strategies used for their isolation see Supplemental Methods). We and others have previously validated this approach by correlating its results with those of Q-PCR, microarray and RNA-seq analyses (data not shown and37,38). Sixty-eight and eighty-nine of these probes yielded uniformly strong or weak signals, respectively, in all tested cell types (not illustrated). However, 54 and 35 probes identified KRAB-ZFPs or clusters that were expressed at higher or lower levels, respectively, in B cells than in all other lineages (Fig. 6A and Fig. S6A). Q-PCR confirmed the B cell-specific pattern of expression of all the differentially expressed genes tested (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. KRAB-ZFP expression in B cells.

A) Heat map of KRAB-ZFP (and control genes) significantly more expressed in B cells than in other hematopoietic lineages, as assessed by NanoString nCounter direct RNA quantification. For the staining strategy used to sort the different populations see supplemental Methods. HPC: hematopoietic progenitor cells, Red: erythrocyte lineage, Myelo/Mega: Myeloid/Megakaryocyte. For B cell population description see Fig. 1 legend. Arrowheads indicate KRAB-ZFP analyzed in panel B. B) Q-PCR analysis performed on cDNA from Thymus and B-enriched splenocytes (spleen B), by using primers specific for the indicated KRAB-ZFP (indicated by arrowheads in panel A and Fig. S6A). a: p=0.0046, b: p=0.0022, c: p=0.0022, d: p=0.041 by Mann-Whitney test, average + SEM is shown, n=6. C) Phylogenetic trees of the depicted KRAB-ZFP, based on ZF exon sequence alignment. Each protein is defined by the genome: mouse=mmus, human=hsap, macaque=mmul, marmoset=cjac, cow=btau, dog=cfam, horse=ecab, rat=rnor, guinea pig=cpor, rabbit=ocun, elephant=lafr, opossum=mdom | query protein | contig and position (contig.start-end). Query protein is depicted as index, in green in upper left and bottom panels, in red in upper right panel. Green: mouse paralogs present in the list of differentially ZFP expressed in B cells (Fig. S4), blue: 1:1 orthologs, aqua: closest rodent paralogs, mustard: closest human genome matches. Right panel, only rodents and human hits are shown (rodents+human). See also Fig. S6.

Only eight of the forty-nine murine KRAB-ZFP most highly expressed in B cells has a human orthologue, based on alignments of their ZF exon sequences (Fig. S6B), consistent with the marked evolutionary divergence of rodents and primates in this gene family39. Nevertheless, one of these conserved B cell-expressed murine KRAB-ZFP is ZFP317, the human ortholog of which has been proposed to play a role in lymphocyte proliferation40 (Fig. 6C). Of the majority of rodent-specific KRAB-ZFPs in our list, some displayed the signs of a significant expansion in this clade. Many paralogs could be found for several of them, including ZFP870, suggesting that they were subjected to positive selection and might have related functions. Noteworthy one of them, ZFP87, has paralogs in the human genome, namely ZNF91 and ZNF43, which are highly expressed in lymphoid cells41.

DISCUSSION

Recent studies have proposed that epigenetic regulators control the development and homeostasis of B cells, notably by determining the accessibility of specific genomic loci to transcription factors. In this work we investigated the role of KAP1, the universal essential cofactor of the large family of KRAB-ZFPs, in the differentiation and function of B lymphocytes.

We inactivated KRAB-ZFP/KAP1-mediated regulation by conditional deletion of the Kap1 locus at the pro-B stage of B cell differentiation. Although the deletion was not complete, mutant mice displayed a clear reduction in mature FO and MZ B splenocytes and in peritoneal B1 cells, with a significant overgrowth of residual wild type over Kap1-deleted cells in the MZ and B1 populations. We also observed an accumulation of T2-FP progenitor cells in the knockout mice, and an even more pronounced accumulation of bone marrow early B progenitors when Kap1-deleted cells were placed in competition with wild type cells. Furthermore, KAP1-defective mice harbored abnormally low levels of steady-state antibodies of all isotypes. In mice kept under pathogen-free conditions, natural antibodies (largely IgM, IgA and IgG3, made in the absence of specific antigens by B1 cells) and antibodies against commensal bacteria and food antigens constitute so called steady-state antibodies42. The observed reduced levels of these antibodies can thus be explained by the lower numbers of B1 cells and/or to a functional defect of these cells in Kap1-deleted mice. Although the latter responded to challenge with antigenic peptides, they displayed faster rates of decay of neutralizing antibodies following viral immunization. Whether this results from a defect in long-lived reactions in germinal centers or from a failure to maintain plasma cells in the bone marrow remains to be defined, but these data indicate that KAP1 contributes to long-term antibody memory. Noteworthy, we did not test whether KAP1 impacts on other B cell functions, such as cytokine production and antigen presentation. Nevertheless, we observed that, while Kap1-depleted mice performed class switch recombination at normal rates, they exhibited a bias towards IgE upon immunization. As IgE are the principal mediators of allergic reactions, it suggests that KAP1 and perhaps specific KRAB-ZFPs may be involved in controlling allergies. Noteworthy, our finding of normal rates of CSR in the absence of KAP1 is in apparent conflict with the recent proposal that KAP1 is needed for CSR43. However, this other work was performed in vitro, and it could be that the two-fold decrease in CSR efficiency detected in this other setting is fully compensated in vivo.

Gene ontology analyses of the transcripts dysregulated in KAP1-deficient T2-FP cells revealed a significant enrichment in genes involved in immune system development. This is consistent with the observed phenotype and further supports a role for KAP1 in B lymphoid differentiation. The DNA mismatch repair (MMR) protein MSH6 was upregulated in both T2-FP and FO cells. The MMR system is needed to maintain genomic stability and components of the MMR regulate signal transducers are involved in cell growth arrest and cell death44. Kap1-deletion also led to dysregulation of factors involved in cytoskeletal rearrangement and migration in response to external stimuli transduced by the BCR and chemokine receptors, such as KLHL6, CXCR5 and SLAM927,45.

Several observations suggest that the loss of KAP1-mediated repression of PTEN, an antagonist of PI3K, plays a prominent role in the phenotype of B-lymphoid kap1 knockout mice. First, PTEN transcripts were upregulatd in Kap1-deleted FO B lymphocytes, correlating with an increase in FoxO1, a factor normally down-regulated by PI3K. Correspondingly, we detected two KAP1-binding sites in the Pten gene, and could document the KAP1-dependent H3K9 trimethylation at one of these sites and at the Pten promoter, altogether indicating direct repression of this gene by KAP1. PI3K, through its role in second messengers production in response to BCR signaling, controls both early and peripheral B cell development and homeostasis, a process modulated by PTEN46. Furthermore, it was previously noted that loss of PTEN leads to an expansion of the MZ and B1 cell compartments and to increased autoantibody production47. Finally, PI3K negatively regulates IgE production48. Therefore, it is tempting to relate the decreased numbers of MZ and B1 cells, the lower levels of steady-state antibodies, and the increased rates of IgE CSR noted in B lymphoid Kap1 KO mice to a loss of KAP1-mediated repression of Pten.

Our chromatin studies also detected sites of KAP1 binding and H3K9me3 deposition near the Msh6 and Slamf9 genes. As for Pten, the promoters of these genes became activated upon KAP1 removal, with H3K9me3 depletion and H3Ac enrichment, correlating with the upregulation of their transcripts in this setting. This strongly suggests that KAP1 directly controls the expression of these genes involved in DNA damage response and cytoskeleton/migration. This could also explain partly the defect in maintenance of long-term antibody memory noted in Kap1-deleted mice, since MSH6 has been involved in control of germinal center homeostasis and SLAM molecules have been shown to be needed for long-term humoral reactions49,50. Finally, Kap1 deletion lead to significant upregulation of the SERine Protease INhibitor clade A3 (Serpina3) F-G genes and the gluthatione S-transferase theta (Gstt) cluster. The functions of the products of these two gene clusters in the B lymphoid lineage are undefined, and the results of our analyses warrant exploring further their role in B cell development.

Genome-wide analysis of KAP1-bound regions revealed that they were enriched in the H3K9me3 repressive histone mark and depleted of modifications associated with active/poised B-specific cis-regulatory regions. This is to our knowledge the first report characterizing KAP1 binding sites in an in vivo adult tissue. It confirms the association of this molecule to facultative heterochromatic regions and strongly supports its role as an orchestrator of gene silencing.

KAP1 has no DNA binding domain and its association to specific genomic loci is governed via other proteins, notably products of the KRAB-ZFP gene family. KRAB-ZFPs constitute the largest group of transcriptional regulators encoded by the mammalian genome, and have been proposed to exhibit tissue-restricted modes of expression7,39. By analyzing the expression of some 300 of them, which account for approximately 85% of the mouse KRAB-ZFPs according to our identification strategies, we determined that approximately one third was highly expressed in most hematopoietic cells, another third globally low in all of these cells, and the last third differentially expressed in the B lineage. Although drawing parallels between human and mouse KRAB-ZFPs might be misleading because of their divergent evolutions39, this pattern of expression is reminiscent of the one described in human lymphoid tissues7. Interestingly, although most KRAB-ZFP genes map to clusters generated by gene duplication of a few ancestors, we often found differential expression of the genes residing within a cluster, strongly suggesting functional divergence of duplicated genes and indicating tight regulation at the single gene level. When we tested for orthologs of B-enriched KRAB-ZFP sequences in several tetrapod genomes, we found that about 80% of them were rodent-specific, a proportion similar to that measured for the entire set of KRAB-ZFP genes39. The targets of most of the identified human orthologs of murine B cell-expressed KRAB-ZFPs are still undefined, but ZNF317 has been proposed to regulate lymphocyte proliferation, and some isoforms are exclusively expressed in spleen, peripheral blood lymphocytes and lungs40. Our results warrant efforts aimed at identifying the KRAB-ZFPs interacting with specific KAP1 targets, for instance Pten, and at determining the consequences of their overexpression or inactivation. Finally, because the rapidly evolving KRAB-ZFP gene family exhibits significant polymorphism in humans, it will be interesting to ask whether nucleotide substitutions in its B cell-expressed members might underlie inter-individual differences in susceptibility to immune-related disorders, such as infections, allergies or auto-immune diseases.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sonia Verp for technical help, Anna Groner, Helen Rowe and Corinne Schär for fruitful discussion, Giovanna Ambrosini, Jacques Rougemont, Patrick Descombes and the Genomics Platform of “Frontiers in Genetics” for help in high-throughput analyses, Fabio Aloisio for histological analysis, Jessica Dessimoz and the EPFL histology core facility, Miguel Garcia and the EPFL flow cytometry core facility, and Florian Kreppel and Stefan Kochanek from University of Ulm for the rAD/VSV-G vector. Part of the computation was performed on the Vital-IT facility www.vital-it.ch of the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics,. This work was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation and the European Research Council to DT. P.G was supported by Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC), Milano, Italy.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meissner A. Epigenetic modifications in pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(10):1079–1088. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Javierre BM, Esteller M, Ballestar E. Epigenetic connections between autoimmune disorders and haematological malignancies. Trends Immunol. 2008;29(12):616–623. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pillai S, Cariappa A. The follicular versus marginal zone B lymphocyte cell fate decision. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(11):767–777. doi: 10.1038/nri2656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montecino-Rodriguez E, Leathers H, Dorshkind K. Identification of a B-1 B cell-specified progenitor. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(3):293–301. doi: 10.1038/ni1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nutt SL, Kee BL. The transcriptional regulation of B cell lineage commitment. Immunity. 2007;26(6):715–725. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jhunjhunwala S, van Zelm MC, Peak MM, Murre C. Chromatin architecture and the generation of antigen receptor diversity. Cell. 2009;138(3):435–448. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huntley S, Baggott DM, Hamilton AT, et al. A comprehensive catalog of human KRAB-associated zinc finger genes: insights into the evolutionary history of a large family of transcriptional repressors. Genome Res. 2006;16(5):669–677. doi: 10.1101/gr.4842106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas JH, Emerson RO. Evolution of C2H2-zinc finger genes revisited. BMC Evol Biol. 2009;9(51) doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman JR, Fredericks WJ, Jensen DE, et al. KAP-1, a novel corepressor for the highly conserved KRAB repression domain. Genes Dev. 1996;10(16):2067–2078. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.16.2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sripathy SP, Stevens J, Schultz DC. The KAP1 corepressor functions to coordinate the assembly of de novo HP1-demarcated microenvironments of heterochromatin required for KRAB zinc finger protein-mediated transcriptional repression. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(22):8623–8638. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00487-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schultz DC, Friedman JR, Rauscher FJ., 3rd Targeting histone deacetylase complexes via KRAB-zinc finger proteins: the PHD and bromodomains of KAP-1 form a cooperative unit that recruits a novel isoform of the Mi-2alpha subunit of NuRD. Genes Dev. 2001;15(4):428–443. doi: 10.1101/gad.869501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schultz DC, Ayyanathan K, Negorev D, Maul GG, Rauscher FJ., 3rd SETDB1: a novel KAP-1-associated histone H3, lysine 9-specific methyltransferase that contributes to HP1-mediated silencing of euchromatic genes by KRAB zinc-finger proteins. Genes Dev. 2002;16(8):919–932. doi: 10.1101/gad.973302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cammas F, Mark M, Dolle P, Dierich A, Chambon P, Losson R. Mice lacking the transcriptional corepressor TIF1beta are defective in early postimplantation development. Development. 2000;127(13):2955–2963. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.13.2955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shin JH, Ko HS, Kang H, et al. PARIS (ZNF746) Repression of PGC-1alpha Contributes to Neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s Disease. Cell. 2011;144(5):689–702. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ziv Y, Bielopolski D, Galanty Y, et al. Chromatin relaxation in response to DNA double-strand breaks is modulated by a novel ATM- and KAP-1 dependent pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(8):870–876. doi: 10.1038/ncb1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolf D, Goff SP. TRIM28 mediates primer binding site-targeted silencing of murine leukemia virus in embryonic cells. Cell. 2007;131(1):46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jakobsson J, Cordero MI, Bisaz R, et al. KAP1-mediated epigenetic repression in the forebrain modulates behavioral vulnerability to stress. Neuron. 2008;60(5):818–831. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowe HM, Jakobsson J, Mesnard D, et al. KAP1 controls endogenous retroviruses in embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2010;463(7278):237–240. doi: 10.1038/nature08674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng L, Pan H, Li S, et al. Sequence-specific transcriptional corepressor function for BRCA1 through a novel zinc finger protein, ZBRK1. Mol Cell. 2000;6(4):757–768. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quenneville S, Verde G, Corsinotti A, et al. In Embryonic Stem Cells, ZFP57/KAP1 Recognize a Methylated Hexanucleotide to Affect Chromatin and DNA Methylation of Imprinting Control Regions. Mol Cell. 2011;44(3):361–372. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell. 2010;38(4):576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rickert RC, Roes J, Rajewsky K. B lymphocyte-specific, Cre-mediated mutagenesis in mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(6):1317–1318. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, et al. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev Biol. 2001;1(4) doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt-Supprian M, Rajewsky K. Vagaries of conditional gene targeting. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(7):665–668. doi: 10.1038/ni0707-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dennis G, Jr., Sherman BT, Hosack DA, et al. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4(5):P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(1):44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroll J, Shi X, Caprioli A, et al. The BTB-kelch protein KLHL6 is involved in B-lymphocyte antigen receptor signaling and germinal center formation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(19):8531–8540. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.19.8531-8540.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Z, Scherer SJ, Ronai D, et al. Examination of Msh6- and Msh3-deficient mice in class switching reveals overlapping and distinct roles of MutS homologues in antibody diversification. J Exp Med. 2004;200(1):47–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slean MM, Panigrahi GB, Ranum LP, Pearson CE. Mutagenic roles of DNA “repair” proteins in antibody diversity and disease-associated trinucleotide repeat instability. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7(7):1135–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heintzman ND, Stuart RK, Hon G, et al. Distinct and predictive chromatin signatures of transcriptional promoters and enhancers in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2007;39(3):311–318. doi: 10.1038/ng1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caron H, van Schaik B, van der Mee M, et al. The human transcriptome map: clustering of highly expressed genes in chromosomal domains. Science. 2001;291(5507):1289–1292. doi: 10.1126/science.1056794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vogel MJ, Guelen L, de Wit E, et al. Human heterochromatin proteins form large domains containing KRAB-ZNF genes. Genome Res. 2006;16(12):1493–1504. doi: 10.1101/gr.5391806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Geen H, Squazzo SL, Iyengar S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of KAP1 binding suggests autoregulation of KRAB-ZNFs. PLoS Genet. 2007;3(6):e89. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Groner AC, Meylan S, Ciuffi A, et al. KRAB-zinc finger proteins and KAP1 can mediate long-range transcriptional repression through heterochromatin spreading. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(3):e1000869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blahnik KR, Dou L, Echipare L, et al. Characterization of the contradictory chromatin signatures at the 3′ exons of zinc finger genes. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geiss GK, Bumgarner RE, Birditt B, et al. Direct multiplexed measurement of gene expression with color-coded probe pairs. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(3):317–325. doi: 10.1038/nbt1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Malkov VA, Serikawa KA, Balantac N, et al. Multiplexed measurements of gene signatures in different analytes using the Nanostring nCounter Assay System. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2(80) doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Payton JE, Grieselhuber NR, Chang LW, et al. High throughput digital quantification of mRNA abundance in primary human acute myeloid leukemia samples. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(6):1714–1726. doi: 10.1172/JCI38248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shannon M, Hamilton AT, Gordon L, Branscomb E, Stubbs L. Differential expansion of zinc-finger transcription factor loci in homologous human and mouse gene clusters. Genome Res. 2003;13(6A):1097–1110. doi: 10.1101/gr.963903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takashima H, Nishio H, Wakao H, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a KRAB-containing zinc finger protein, ZNF317, and its isoforms. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288(4):771–779. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bellefroid EJ, Marine JC, Ried T, et al. Clustered organization of homologous KRAB zinc-finger genes with enhanced expression in human T lymphoid cells. EMBO J. 1993;12(4):1363–1374. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05781.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manz RA, Hauser AE, Hiepe F, Radbruch A. Maintenance of serum antibody levels. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:367–386. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jeevan-Raj BP, Robert I, Heyer V, et al. Epigenetic tethering of AID to the donor switch region during immunoglobulin class switch recombination. J Exp Med. 2011;208(8):1649–1660. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hawn MT, Umar A, Carethers JM, et al. Evidence for a connection between the mismatch repair system and the G2 cell cycle checkpoint. Cancer Res. 1995;55(17):3721–3725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ansel KM, Ngo VN, Hyman PL, et al. A chemokine-driven positive feedback loop organizes lymphoid follicles. Nature. 2000;406(6793):309–314. doi: 10.1038/35018581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baracho G, Miletic A, Omori S, Cato M, Rickert R. Emergence of the PI3-kinase pathway as a central modulator of normal and aberrant B cell differentiation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23(2):178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suzuki A, Kaisho T, Ohishi M, et al. Critical roles of Pten in B cell homeostasis and immunoglobulin class switch recombination. J Exp Med. 2003;197(5):657–667. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doi T, Obayashi K, Kadowaki T, Fujii H, Koyasu S. PI3K is a negative regulator of IgE production. Int Immunol. 2008;20(4):499–508. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peled JU, Sellers RS, Iglesias-Ussel MD, et al. Msh6 protects mature B cells from lymphoma by preserving genomic stability. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(5):2597–2608. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwartzberg PL, Mueller KL, Qi H, Cannons JL. SLAM receptors and SAP influence lymphocyte interactions, development and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(1):39–46. doi: 10.1038/nri2456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.