Abstract

Robust inter-individual variation in pain sensitivity has been observed and recent evidence suggests that some of the variability may be genetically-mediated. Our previous data revealed significantly higher pressure pain thresholds among individuals possessing the minor G allele of the A118G SNP of the mu-opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) compared to those with two consensus alleles. Moreover, ethnic differences in pain sensitivity have been widely reported. Yet, little is known about the potential interactive associations of ethnicity and genotype with pain perception. This study aimed to identify ethnic differences in OPRM1 allelic associations with experimental pain responses. Two-hundred and forty-seven healthy young adults from three ethnic groups (81 African Americans; 79 non-white Hispanics; and 87 non-Hispanic whites) underwent multiple experimental pain modalities (thermal, pressure, ischemic, cold pressor). Few African Americans (7.4%) expressed the rare allele of OPRM1 compared to non-Hispanic-whites and Hispanics (28.7% vs. 27.8%, respectively). Across the entire sample, OPRM1 genotype did not significantly affect pain sensitivity. However, analysis in each ethnic group separately revealed significant genotype effects for most pain modalities among non-Hispanic-whites (ps<0.05) but not Hispanics or African Americans. The G allele was associated with decreased pain sensitivity among whites only; a trend in the opposite direction emerged in Hispanics. The reasons for this dichotomy are unclear but may involve ethnic differences in haplotypic structure or A118G may be a tag-SNP linked to other functional polymorphisms. These findings demonstrate an ethnic-dependent association of OPRM1 genotype with pain sensitivity. Additional research is warranted to uncover the mechanisms influencing these relationships.

1. Introduction

Individuals vary dramatically in their presentation of, and responses to, pain and such variations seem to be more pronounced when considering influential factors such as ethnicity [1;14;22;25]. Despite these clinically-known differences, the mechanisms explicating such variability have yet to be fully understood. Emerging translational research suggests that differences in pain perception may be partially mediated by single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of identified pain genes [12;13;15;44-47;58;62;63] while others have noted that combinations of SNPs, called haplotypes, might have joint effects[13;49;70]. Among the most studied SNP candidates for their putative influence on pain are catechol-O-methyl-transferase (COMT) Val158Met, Delta-opioid receptor (OPRD1) Phe27Cys and T307C, Vanilloid receptor subtype-1 gene (TRPV1) Met315Ile and Ile585Val, and Mu-opioid receptor (OPRM1) A118G, the variant of focus in this study.

The A allele of the A118G polymorphism encodes asparagine at residue 40 in the protein, while the G allele results in a non-conservative aspartic acid substitution. G allele frequencies vary by ethnicity, ranging from 0.12 – 0.20 in whites (non-Hispanic, European descent), 0.19 – 0.24 in non-white Hispanics, and 0.01 – 0.04 in African Americans (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/snp_ref.cgi?rs=1799971). The G allele has been associated with opioid analgesia, tolerance and dependence [5;36;37;50-52;55;57]. A118G genotype also has been associated with post-operative pain intensity, increased opioid demands, and acute pain severity in various post-operative populations [10;11;18;32;88;89], and in experimental pain [89;92], though the direction and magnitude of these effects varies[86]. We previously demonstrated a significant association of A118G with pressure pain thresholds (PPTh) in a sex-dependent fashion whereby males, but not females, with AG or GG genotype had increased PPTh. A sex-by-genotype interaction also emerged for heat pain ratings at 49 °C, with the G allele being associated with reduced ratings in men but higher ratings in women [15]. Other investigators showed that pain-related evoked potential responses were lower among individuals with G alleles compared to AA homozygotes [56]. In a case-control population-based clinical sample, others found no evidence of association between OPRM1 SNPs (including A118G) and increased pain sensitivity or chronic widespread pain [34].

These previous studies of OPRM1 have included little ethnic diversity despite solid evidence of vast differences in clinical presentation and experience of pain and analgesia across ethnic groups [1;8;14;24;41;42]. Indeed, relative to non-Hispanic whites, African Americans report higher levels of pain and disability associated with several pain conditions[1;3;24-28;67;68;82], including post-operative pain[29;43;53]. In addition, multiple studies have demonstrated greater experimental pain sensitivity among African Americans [6;7;17;30;59-61;69]. Though literature is limited regarding Hispanics, higher clinical pain and inadequate analgesia have been reported [40;54;67;81;83;84]. Among Asians, carriers of the rare G allele on A118G revealed generally increased clinical pain and analgesic response differences [19;32;77-79;88-90], although limited ethnic-group comparisons exist.

Given that independently both OPRM1 genotype and ethnic background have been associated with pain responses, examining the combined influences of ethnicity and A118G on experimental pain sensitivity in healthy adults could lend important insight into variations in pain experience and potentially better inform clinical treatment. This study sought to determine ethnic differences in A118G allele frequencies and to test for ethnic group-by-gene interactions with experimental pain responses.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Participant included two hundred and forty-seven healthy young adults (118 male, 129 female) that were distributed across three ethnic groups (81 African Americans, 79 Hispanics, and 87 non-Hispanic whites). The mean age of the sample was 23.7 years with a standard deviation of 7.1 years (range 18-54 years). Participants were recruited through IRB-approved advertisements posted in the local and university community to participate in experimental pain research conducted at the University of Florida, which included assessment of multiple experimental pain responses. All participants were healthy nonsmokers and were free of systemic medical conditions, clinical or chronic pain, psychiatric disturbance, substance abuse, or use of centrally acting medications. Written and verbal informed consents were obtained from each participant.

2.2 Experimental Pain Measures

Each participant completed three experimental sessions over a 1-2 week period. First, an introductory session was conducted, which included completion of questionnaires, including health history, and a brief interview. Following that, two experimental pain testing sessions were conducted, with two of the following four experimental pain induction procedures conducted during each session: thermal pain, pressure pain, ischemic pain, and cold-pressor pain (described below). Participants were randomly assigned to one of four possible testing orders (Table 1). The order of presentation was randomized such that either the thermal or pressure pain modalities were always conducted first, followed by a 10-min rest period. This was followed by either cold-pressor or ischemic pain procedures, which were always conducted last and in separate sessions to avoid carryover effects. For females, sessions were always conducted during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (days 4-10) following menses. Subjects refrained from any over-the-counter medications for at least 24 hours prior to testing and abstained from caffeine for at least 4 hours before testing. Genotyping of the A118G SNP was conducted from blood samples ascertained during the experimental sessions. All procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committee at the University of Florida-Gainesville.

Table 1.

Randomized Order of Experimental Pain Testing by Sessions

| Order Number | Session 1 | Session 2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Heat then Cold Pressor | Pressure then Ischemic |

| 2 | Heat then Ischemic | Pressure then Cold Pressor |

| 3 | Pressure then Cold | Pressor Heat then Ischemic |

| 4 | Pressure then Ischemic | Heat then Cold Pressor |

Quantitative sensory testing (QST) modalities included thermal, ischemic, cold pressor, pressure pain and temporal summation of thermal pain. The QST assessments measured sensory domains of intensity, tolerance, threshold as well as the affective dimension of suprathreshold ratings of unpleasantness.

Thermal Pain Procedures

Contact heat stimuli were delivered using a computer-controlled Medoc Thermal Sensory Analyzer (TSA-2001, Ramat Yishai, Israel), a 30 mm × 30 mm Peltier element-based stimulator. Non-repetitive sites along the ventral forearm were used to administer four trials each for heat pain thresholds and heat pain tolerances using an ascending method of limits. From a baseline of 32 °C, contactor temperature increased at a rate of 0.5 °C per second (s) until the subject responded by pressing a button on a handheld device. Upon pressing the button, the heat delivery system automatically stopped the stimulus and cooled the thermode to baseline. The thermode was then moved to another location on the ventral forearm to avoid stimulation of the same receptors. Four trials of heat pain threshold (e.g., when the participant first felt pain) were administered, followed by 4 trials of heat pain tolerance (e.g., when the participant indicated they no longer felt able to tolerate the pain). Inter-stimulus intervals of at least 30 s were maintained between successive stimuli to avoid sensitization or habituation of cutaneous receptors. The cutoff temperature to avoid tissue damage for all trials was 52 °C. Average values were calculated from all 4 trials for both heat pain threshold (HPTh) and tolerance (HPTo). These scores were then combined and converted to standardized z-scores to comprise the “mean heat pain scores” in accordance with our previously reported work on factor and cluster analyses of experimental pain modalities [31]. It is important to note that since temporal summation (TS) loaded on a separate factor, TS was not included in these mean heat pain scores, but was determined as described below.

Temporal Summation of Heat Pain

Brief repetitive suprathreshold thermal stimuli were applied to the right dorsal forearm to elicit temporal summation of pain. Temporal summation was assessed at two different heat pain stimulus intensities. Two inter-trial stimulus intensities were used, 39 °C and 40 °C, and the two target temperatures were 49 °C and 52 °C, respectively. The target temperature was delivered for approximately 0.5-s or less, with an approximate 2.0-s inter-pulse interval at the inter-trial intensity. One set of 10 stimuli was administered for each target temperature of 49 °C and 52 °C, and each set of 10 trials lasted approximately 30-s. Subjects rated the intensity of each pulse using a 101-point scale. The procedure continued for up to 10 trials, or until the subject provided a rating of 100 or requested that the testing be terminated. One set of 10 stimuli was administered for each target temperature of 49 °C and 52°C, and each set of 10 trials lasted approximately 30-s. The interval between tests was approximately 3-5 min, allowing for a recovery period between each set of trials, at which time the thermode was moved to a different site on the forearm. The average pain rating across all ten trials from each temperature was calculated.

Pressure Pain Threshold

A handheld pressure algometer (Pain Diagnostics and Therapeutics, Great Neck, NY) with a 1-cm diameter rubber tip was used to assess pressure pain threshold. A constant rate of pressure was applied at the rate of 1 kg/s [38], as this relatively slow application rate would reduce artifact associated with reaction time [39]. Pressure stimulus was applied to three sites bilaterally in a counter-balanced fashion to the center of the upper trapezius (posterior to the clavicle), the masseter (approximately midway between the ear opening and the corner of the mouth), and the ulna (on the dorsal forearm, approximately 8 cm distal to the elbow). These sites were chosen because they are widely used in clinical settings, good inter-examiner reliability at these sites has been reported, and normative values are available [2;16;21]. Three trials were delivered to each of these aforementioned sites. After each individual trial, the device was moved to an adjacent location on the specified site with an approximately 10-second inter-trial interval. There was at least a 30-s inter-site interval during which the new site was located and a new set of three trials began. The average of the three trials was calculated for each site.

Ischemic Pain Procedure

A modified submaximal effort tourniquet test was performed [31;64;66]. The right arm was exsanguinated by elevating it above heart level for 60-s. Then the arm was occluded with a standard blood pressure cuff inflated to 240 mm Hg. At that point, participants were instructed to perform 20 hand-grip exercises of 2-s duration at 4-s intervals at 50% of their maximum grip strength. Subjects continued until the perceived pain was deemed intolerable or for 15-min, whichever came first. Each minute, subjects were prompted to rate the intensity and unpleasantness of their arm pain below the level of the cuff. Numerical and verbal descriptor box scales were utilized for ratings of pain intensity and unpleasantness [76]. These scales assess both the sensory (intensity) and affective (unpleasantness) dimensions of pain on 0-20 point rating scales that display verbal descriptors at appropriate points along the numerical scale determined by cross-modality matching procedures. Sum scores were computed for the pain intensity (Int) and pain unpleasantness (Unpl) ratings across all 15 minutes of the test. If subjects terminated prematurely, their last values of Int and Unpl were carried forward for the remainder of the time points in the observation. The time required to reach ischemic pain threshold (IPTh) and ischemic pain tolerance (IPTo) were recorded in seconds. Standardized scores for each of the tests (IPInt, IPUnpl, IPTo, IPTh) was calculated and then combined into one Ischemic Pain index.

Cold Pressor

The cold pressor test was used to assess tonic pain stimuli activating slow-conducting C-fibers. With temperature maintained (±0.1 °C) by a refrigeration unit (Neslab, Portsmouth, NH) and constantly circulating to prevent local warming, participants immersed their hand up to the wrist with fingers spread apart into 5 °C water. Participants were instructed to keep their hand in the water until the pain became intolerable or until the 5-min testing interval had been reached, at which point they could remove their hand from the water. At 30-s intervals, subjects rated the unpleasantness (CPUnpl) and intensity (CPInt) of the cold pressor pain using the 0-100 box scales. The average of these scores was calculated across the 5-min testing interval. Cold pressor threshold (CPTh) and tolerance (CPTo) also were recorded in seconds [4;73].

2.3 Genotyping

Genomic DNA samples were diluted to10 ng/μl and placed on 96-well plates for high-throughput genotyping of the A118G SNP (rs1799971). SNP genotyping was performed at the University of Florida Center for Pharmacogenomics using the Applied Biosystems 7900 HT SNP genotyping platform, using an Applied Biosystems TaqMan® assay for that SNP (c__6850074_1). A few blanks and duplicates were used for quality control, and a further quality step was the random selection of 10 samples for re-genotyping using a restriction enzyme based system. In this method, 20 ng of DNA template was used in polymerase chain reaction to amplify a 150-bp product from the OPRM1 gene, with annealing temperature of 58 °C using HotStar enzyme (Qiagen). The forward primer was designed with a base substitution at the 2nd to last base, to force the integration of a α TaqI restriction enzyme site into the PCR product, that would allow the A and G alleles to be distinguished (G allele-carrying product is cut by the enzyme). The forward primer was 5′-GTCAACTTGTCCCACTTAGATTGC, and the reverse primer was 5′-GCACACGATGGAGTAGAGGG. The PCR product was digested with αTaqI per manufacturer’s instructions (New England Biolabs), and fragments separated on an 8% native polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with ethidium bromide for DNA visualization. Genotypes were read as follows, with controls used for detection of partial digest: AA homozygote = 150-bp product only; GG homozygote = 127 bp + 23 bp only; AG heterozygote = all three fragments. Hardy-Weinberg analysis of the genotype data showed no disequilibrium.

2.4 Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each pain test. As described by Hastie et al. [31] and Ribeiro-Dasilva et al. [72], standardized pain indices (Z-scores) were calculated for each pain test by dividing each subject’s score by the sample mean which provides a measure with a sample mean at 0 and an SD=1.

All standardized scores were calculated so that positive scores indicate lower pain sensitivity (i.e. greater threshold and tolerance, lower pain ratings) and negative scores indicate higher pain sensitivity. Consistent with our earlier work in reporting standard Z-scores, higher values of threshold and higher tolerance to painful stimuli equate to decreased, or lower, pain sensitivity. To maintain consistency, pain rating values have been reversed scored to be consistent with such reports of threshold and tolerance ratings.

These scores were aggregated to provide an overall composite pain response score and a modality pain score for heat, cold, ischemic, and pressure measures because of the collinearly of the pain measures collected. It is also important to note that based on our previous report of factor analysis of experimental pain modalities, Heat Pain scores were derived from HPTo, HPTh and average pain ratings but not from Temporal Summation (i.e change) scores, the latter of which tend to form their own factor [31]. For procedures in which participants discontinued prematurely, the last observation was carried forward for subsequent values.

The general linear model (GLM) was used to test for genetic differences (OPRM1) as a function of race/ethnicity on the measures of experimental pain response (e.g. overall/aggregate, heat, cold, ischemic, and pressure). The rare allele variants of GG and AG were combined and tested against the common AA variant as described by [86]. The primary hypothesis proposed a significant gene–by–race/ethnicity interaction for each pain modality Z-score as well as on the composite pain standardized Z-score. With regard to meditational effects, one option would be to test the interaction of gene variants within each ethnicity/raceI. However, we chose to test the interaction of each gene variant separately across race/ethnicity. By doing so, we were able to more clearly demonstrate the effect of the G allele in Hispanics and a trend (albeit non-significant) in African Americans, which were opposite effects compared to non-Hispanic whites. Despite the low frequency of G allele present in African Americans, we have reported effect sizes (table 4) testing each gene across the three race/ethnicity groups. Age and several measures of psychosocial factors known to be associated with pain were used as covariates. Sex was also included as a covariate but not a main effect because of the limited number of African Americans in the sample with the rare G allele (that is, AG or GG genotype). Analysis was also performed excluding the sex variable without substantive differences.

Table 4.

Effect Sizes and Significance Values for Pair-wise Comparisons of AA versus AG Alleles of the A118G SNP on the OPRM1 gene by Ethnic Group

| Experimental Pain Modality Index | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ethnic Group

Comparisons |

Composite Pain D (p) |

Heat Pain D (p) |

Ischemic Pain D (p) |

Pressure Pain D (p) |

Cold Pressor D (p) |

|

| Alleles | ||||||

|

AG/GG

|

NHW vs. Hispanic |

−1.209 (<.001) |

−1.527 (<.001) |

−0.817 (0.015) |

−0.307 (0.341) |

−0.846 (0.006) |

| Alleles | NHW vs. African American |

−0.945 (0.028) |

−1.257 (0.009) |

−0.688 (0.113) |

−0.480 (0.257) |

−0.761 (0.060) |

| AA | NHW vs. Hispanic |

−0.093 (0.592) |

−0.263 (0.150) |

−0.023 (0.934) |

−0.018 (0.922) |

−0.165 (0.320) |

| Allele | NHW vs. African American |

−0.302 (0.252) |

−0.189 (0.290) |

−0.0859 (0.823) |

−0.099 (0.569) |

−0.240 (0.014) |

NHW=non-Hispanic white (reference group for comparisons); Effect sizes shown as Cohen’s D

Significance was set at the α=0.05 level. All analyses were conducted using SPSS statistical package version 18.

3. Results

3.1 Sample

The number of participants was comparable across the three ethnic groups and gender distribution was similar across genotype groups for Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites. Consistent with previous literature and database gene frequency, the G allele was significantly less frequent among African Americans compared to the other two groups. Descriptive data of gender and genotype are presented in Table 2 while the raw scores for each experimental pain modality by ethnicity and allele are presented in Table 3. Effects sizes and significance values for all pair-wise comparisons are reported in Table 4.

Table 2.

Demographic Information by Ethnicity and Genotype of A118G SNP of the OPRM1 Gene

|

AFRICAN AMERICANS (n=81) (32.8% of total sample) |

NON-HISPANIC WHITES (n=87) (35.2% of total sample) |

HISPANICS (n=79) (32.0% of total sample) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | AG/GG | AA | AG/GG | AA | AG/GG | |

| Number (%) | 75 (92.6%) | 6 (7.4%) | 62 (71.3%) | 25 (28.7%) | 57 (72.2%) | 22 (27.8%) |

| Males | 36 | 6 | 25 | 13 | 30 | 8 |

| Females | 39 | 0 | 37 | 12 | 27 | 14 |

| Age (Mean, SD) | 23 (18-52) | 25 (19-38) | 25 (18-54) | 26 (18-53) | 23 (18-51) | 22 (18-43) |

Table 3.

Means and Standard Deviations on Experimental Pain Raw Scores by Ethnicity and Genotype of A118G SNP of the OPRM1 Gene

|

AFRICAN AMERICANS (n=81) |

NON-HISPANIC WHITES (n=87) |

HISPANICS (n=79) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | AG/GG | AA | AG/GC | AA | AG/GG | |

| Experimental Pain Modalities | (n=75) | (n=6) | (n=62) | (n=25) | (n=57) | (n=22) |

| Heat Pain Threshold (average) | 42.0 (3.6) | 42.3 (2.6) | 41.2 (3.2) | 42.7 (3.2) | 41.8 (3.1) | 40.8 (4.0) |

| Heat Pain Tolerance (average) | 46.2 (3.0) | 45.4 (2.9) | 47.1 (2.6) | 48.2 (2.2) | 46.4 (2.6) | 45.7 (3.6) |

| Highest Intensity at 49 °C | 72.1 (23.8) | 90.6 (19.5) | 68.7 (22.8) | 54.5 (24.1) | 74.5 (24.5) | 84.0 (22.0) |

| Highest Intensity at 52 °C | 81.4 (18.4) | 92.4 (13.3) | 80.3 (20.9) | 68.7 (26.2) | 84.4 (19.6) | 89.7 (17.3) |

| Avg. Pressure Pain Trapezius (kg) | 5.8 (2.2) | 5.1 (2.7) | 6.5 (2.4) | 7.1 (2.6) | 5.8 (2.3) | 6.6 (2.1) |

| Avg. Pressure Pain Masseter (kg) | 3.0 (1.1) | 2.3 (1.1) | 3.0 (1.3) | 3.3 (1.6) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.4 (1.5) |

| Cold Pressor Threshold (sec) | 16.6 (18.3) | 6.8 (5.1) | 19.3 (15.0) | 17.9 (14.5) | 18.0 (19.3) | 15.2 (12.5) |

| Cold Pressor Tolerance (sec) | 51.6 (70.3) | 31.7 (38.6) | 119.9 (115.8) | 146.8 (121.2) | 75.9 (99.6) | 58.2 (70.7) |

| Cold Pressor Intensity | 61.7 (19.4) | 71.7 (24.7) | 53.0 (19.3) | 43.0 (16.4) | 63.3 (23.1) | 64.8 (18.6) |

| Cold Pressor Unpleasantness | 56.7 (19.4) | 64.5 (16.2) | 47.0 (22.2) | 38.3 (16.1) | 59.7 (23.0) | 58.7 (20.9) |

| Ischemic Pain Threshold (sec) | 178.5 (150.4) | 214.2 (295.8) | 158.8 (153.2) | 240.8 (188.5) | 187.5 (170.4) | 143.9 (116.1) |

| Ischemic Pain Tolerance (sec) | 446.4 (266.3) | 344.0 (290.9) | 529.7 (277.3) | 565.0 (256.1) | 464.8 (285.3) | 440.7 (261.0) |

Overall Composite Pain

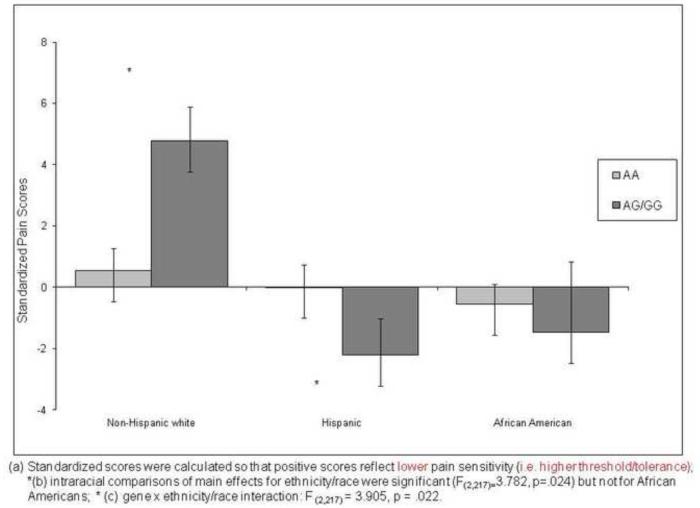

Figure 1 presents the adjusted mean overall composite pain response scores for each race/ethnic group by A118G allele. The main effect of gene was not significant, but there was a significant race/ethnicity difference [F (2,217) = 3.782. p = .024)] as well as a significant gene × race/ethnicity interaction [F (2,217) = 3.905, p = .022)]. Planned pair-wise comparisons within race indicated that whites homozygous for the A allele had significantly greater pain sensitivity than those with one or more G alleles, whereas for Hispanics, the opposite pattern emerged. There were no genotype group differences among African Americans. Although genotype was not significantly associated with pain responses within African Americans, a pattern similar to that of Hispanics emerged with decreased overall threshold and tolerance and thus increased pain sensitivity, and that was in the opposite direction from non-Hispanic whites.

Figure 1.

Ethnic Differences on Standardized Composite Pain Score by A118G Allele of the OPRM1 Gene

Heat Pain

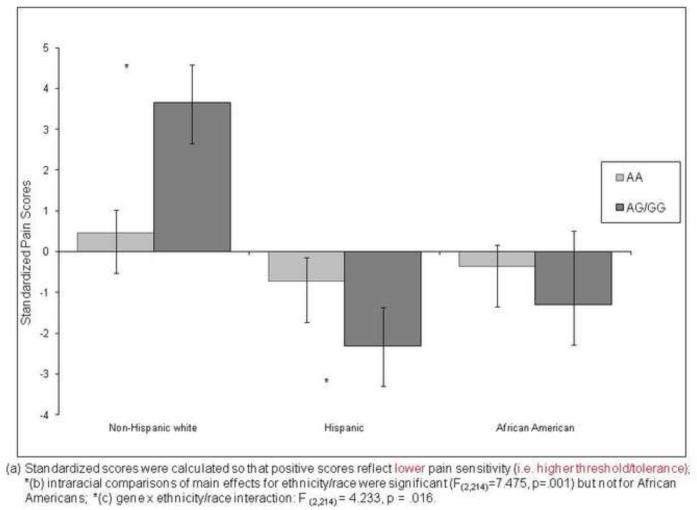

Figure 2 presents the adjusted mean heat pain scores for each race/ethnic group by A118G allele. The main effect of race/ethnicity was significant [F (2,214) = 7.475, p = .001)], but the gene main effect was not. However, a significant gene × race/ethnicity emerged [F (2,214) = 4.233, p = .016)]. Planned pair-wise comparisons within race indicated that whites with AA had significantly greater pain sensitivity than those with at least one copy of the G allele, whereas for Hispanics, those with the AA allele had significantly lower pain sensitivity than those with at least one copy of the G allele. There were no significant genotype group differences among African Americans, but the trend was similar to Hispanics and opposite that of non-Hispanic whites.

Figure 2.

Ethnic Differences on Standardized HEAT Pain Scores by A118G Allele of the OPRM1 Gene

Ischemic Pain

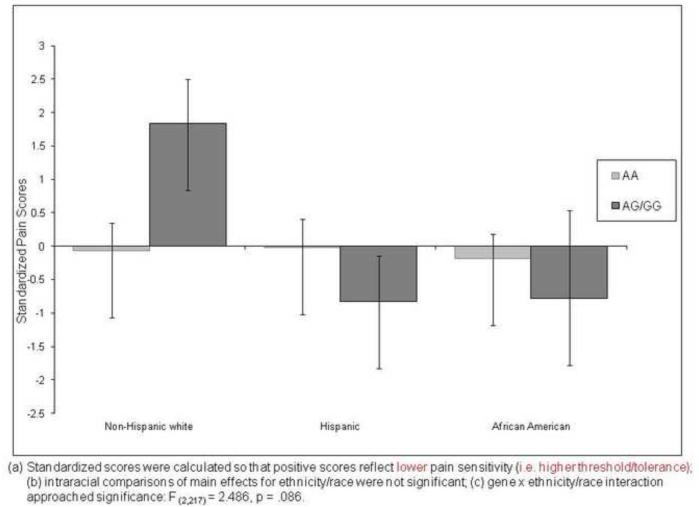

The main effects of race/ethnicity and gene were not significant. However, the gene × race/ethnicity interaction effect approached significance [F (2,217) = 2.486, p = .086)]. Planned pair-wise comparisons within race indicated that whites with AA allele had significantly greater ischemic pain sensitivity than those with the G allele, where as for Hispanics, those with the AA had significantly lower ischemic pain sensitivity than those with the G allele. There were no differences among African Americans although the trend of pain response was similar to Hispanics (i.e. more pain sensitive) and opposite that of non-Hispanic whites. These data are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Ethnic Differences on Standardized ISCHEMIC Pain Scores by A118G Allele of the OPRM1 Gene

Pressure Pain

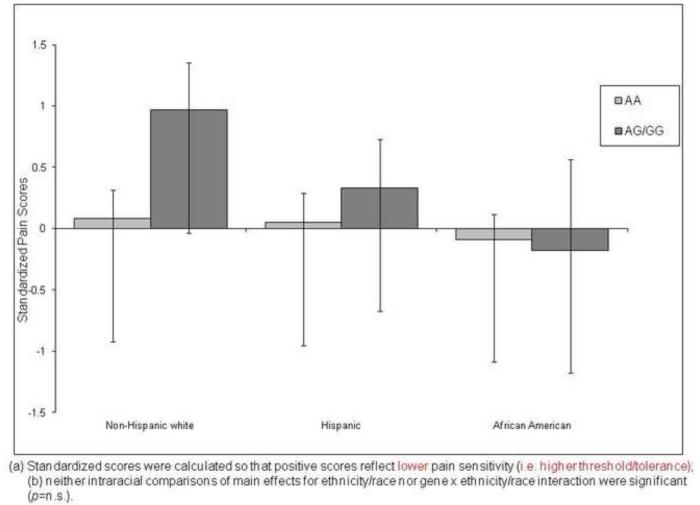

Figure 4 presents the adjusted mean overall pressure response scores for each race/ethnic group by A118G allele. The main effects of race/ethnicity and gene, and the gene × race/ethnicity interaction were not significant.

Figure 4.

Ethnic Differences on Standardized PRESSURE Pain Scores by A118G Allele of the OPRM1 Gene

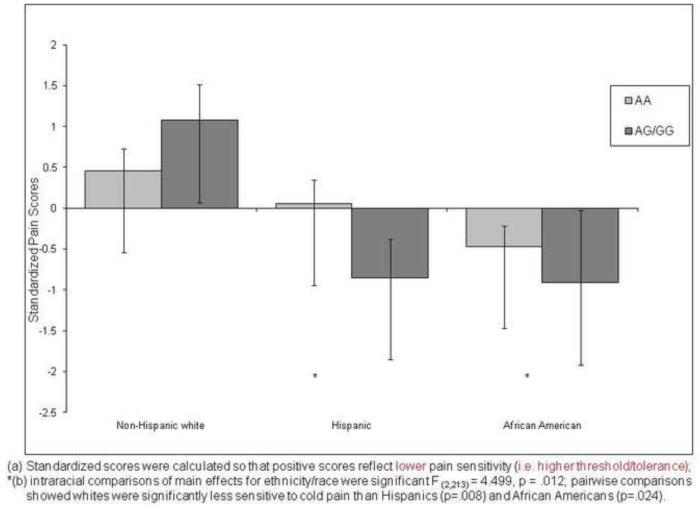

Cold Pressor Pain

Figure 5 presents the adjusted mean overall cold pressor pain response scores for each race/ethnic group by A118G allele. The main effect of race/ethnicity was significant [F (2,213) = 4.499, p = .012). However, the main effect of gene and the gene × race/ethnicity interaction effect were not significant. Pair-wise comparisons indicated that whites were significantly less sensitive to cold pain than Hispanics (p=.008) or African Americans (p=.024). Both minority groups showed similar patterns of decreased threshold and tolerance and thus increased pain sensitivity relative to non-Hispanic whites.

Figure 5.

Ethnic Differences on Standardized COLD PRESSOR Pain Scores by A118G Allele of the OPRM1 Gene

4. Discussion

4.1 Review of Study Findings

These results extend our previous findings and demonstrate an ethnic-dependent association of the OPRM1 genotype with experimental pain that is independent of sex. Notably, genetic associations with thermal and ischemic pain modalities emerged only among non-Hispanic whites. Among those with at least one copy of the G allele, white participants displayed decreased thermal and ischemic pain sensitivity, while among Hispanics, the trend was toward increased pain sensitivity. For composite pain scores, the same pattern emerged. The reasons for this interaction of ethnicity and OPRM1 genotype are not clear. However, we can speculate that functional effects of A118G variants differ by ethnicity, possibly due to linkage to nearby other functional polymorphisms (of differing frequency) or gene-gene interactions with other protein variants that differ in frequency among groups (e.g., a genetic-based difference in opioid metabolism). Indeed, others have previously demonstrated interactive effects of OPRM1 with COMT [49;70]. Since the most-studied COMT SNPs show different allele frequencies across ethnic groups, this could potentially explain differences in the association of OPRM1 with pain phenotypes. Alternatively, in the context of the present experimental pain stimulation, activation of the endogenous opioid system might be a more robust modulatory pathway among whites compared to Hispanics, since greater activation of the variant mu-opioid receptor by the endogenous ligand is the putative mechanism whereby the G-allele confers reduced pain sensitivity. Further investigation including stress levels, HPA-axis activation, and the role of A118G on pain might offer insight into these varying effects across ethnicities. Indeed, others [33;87] have shown differences in cortisol response to an opioid antagonist, with carriers of the G-allele demonstrating increased activation which was population-specific.

Notable to highlight are the types of pain modalities employed and the populations studied. Few have investigated genetic associations with experimental pain across ethnic groups. Much of the current literature studying variations in pain related to A118G have done so in primarily Asian samples [35;89-91], where the rare G-allele is more common (40-50%) compared to ethnic groups studied herein. Huang et al [35] reported no influence of the A118G on pressure pain sensitivity in an all-female Asian sample. This appears contrary to our previous report [15] of A118G’s influence on pressure pain sensitivity and the current findings; however, our previous study demonstrated a significant association only among males, and neither of our samples included Asians. Zhang et al [89] reported the role of A118G on pre-operative electrical pain sensitivity and post-operative fentanyl consumption among a Chinese gynecological sample whereby GG homozygotes reported significantly lower pain tolerance compared to AG and AG genotypes, which conflicts with the current and previous findings based on participants of European descent [15;56]. That was a homogenous all-female Asian population, with an electrical stimulus compared to the modalities employed herein (e.g., heat, cold, ischemic). Though not involving experimental pain, Hernandez-Avila et al [33] demonstrated a significant ethnicity × OPRM1 genotype interaction. Specifically, European Americans with one copy of the G-allele showed significantly greater whole-blood cortisol response levels to naloxone compared to AA homozygotes, while no genetic association was observed among Asians.

In our current study, the G-allele was significantly associated with pain perception, but this relationship was ethnicity/race-dependent. The G-allele was associated with decreased pain sensitivity among non-Hispanic whites but tended to be associated with increased pain in Hispanics across most pain modalities. While we controlled for the effects of gender, it is important to note the extremely low representation of G-allele among African Americans (six males; no females). This is a limiting factor for interpreting results among African Americans, but amongst non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics, percentages were comparable in allele expression and genders. Future studies might consider employing similar pain modalities and account for admixture among ethnic groups. Given hormonal influences, gender might explain some of the differences in other investigations and should also be taken into account.

4.2 Clinical Implications

While this study involved young healthy adults undergoing experimental pain testing, it has potential clinical implications. Emerging literature reports the role the A118G SNP of OPRM1 in clinical pain and analgesic consumption as shown in those undergoing cesarean section, hysterectomy, knee arthroplasty, or orthognathic surgeries [10;11;18;32;75]; chronic pain patients [80] and life-threatening diseases such as diabetes [9] and cancer [48;71]. However, most of these studies involve ethnically-homogenous populations [9-11;32;48;49;75;89]. Nielsen et al [65] demonstrated ethnic group differences in epigenetic modification of the OPRM1 promoter among former addicts (versus healthy controls) with differences in methylation shown across ethnic groups primarily for African Americans rather than Hispanics or Caucasians. Although this may not directly explain our findings, it suggests another mechanism for ethnic-dependent genetic associations with OPRM1. Whether these associations of OPRM1 with clinical phenotypes demonstrate ethnicity/race-dependence, as with the present findings, is an important topic for future research.

There is emerging evidence of the effects of ethnicity and OPRM1 genotype on both post-procedural pain as well as analgesic use [18;20;32;77-79]. Reyes-Gibby et al. [70] first reported the joint effects of OPRM1 and COMT on opioid consumption among lung cancer patients, and Kolesnikov [49] revealed similar joint-gene effects on post-operative morphine consumption, although the samples were exclusively Caucasian. While multiple clinical studies have suggested an association of A118G with pain and/or analgesia, in their systematic review, Walter and Lotsch [86] found no consistent association of A118G with analgesic responses across several clinical studies. The reasons for that inconsistency vary, but the disparate ethnic compositions of the samples, the wide range of G-allele expression across ethnicities (from 0.8% in Sub-Saharan Africans to over 40% in Asians), and the putative differences in activation and response of endogenous opioid system may contribute to the conflicting results. Other SNPs on OPRM1 may also play a role as shown by altered experimental pain perception and response to morphine among healthy, primarily female, Caucasians [74]. Contrary to previous reports and this study, A118G showed much smaller differences while rs563649 showed greater functional consequences. The limited ethnic diversity and one summary pain score might help explain the inconsistencies, but it supports the value of future analyses with additional putative SNPs and halpotyping.

Additional research to further characterize the role of A118G in pain and analgesia could lend important information for therapeutic interventions. Despite somewhat compelling early reports, emerging evidence suggests the G allele has varied influence with many exogenous and endogenous factors[86] including ethnicity, as with this present study.

4.3 Limitations and Generalizability

While this study is one of the first to present novel information on potential genetic associations with experimental pain sensitivity across three ethnic groups, it is not without limitations. First, the representation of African Americans possessing the G-allele is quite low, mitigating conclusive intraracial analysis in that group. Given clinical reports of significant differences in pain experiences for African Americans [23;28], it would be important to examine a larger sample to determine the role of the G-allele. Second, substantial genetic and sociocultural heterogeneity exist especially each ethnic group, especially Hispanics, which warrants further consideration. It is quite possible that admixture and population stratification particularly amongst Hispanics, but also in non-Hispanic whites, could potentially bias these results. Future studies with larger ethnic samples are needed. Third, it might behoove future investigators to incorporate ancestry informative markers for as part of the ethnic analysis. Fourth, this study applied a candidate-gene approach to examine the association of a single SNP with pain sensitivity. Assessing additional SNPs [74], haplotype or haploblock analyses might provide additional insight into the role of this gene in pain perception and perhaps risk of developing chronic pain[13]. Likewise, a genome-wide association study represents a more broad-based approach investigating genetic contributions to ethnic differences in pain. However, the sample size requirements and associated costs currently pose formidable challenges although this may soon become feasible. Other approaches such as deep sequencing also might eventually become more affordable and informative. Finally, this current sample is a non-clinical population of young healthy adults, and the extent to which pain processing in a healthy biological system generalizes to individuals with complex disease is yet unknown.

4.4 Future Directions

Though investigations of the genetics of pain are burgeoning, few studies have examined genetic associations with experimental pain in multi-ethnic samples. Indeed, a common approach has been to exclude all “non-white” samples in genetic association studies in order to sidestep population stratification. In addition to using multiple pain modalities, making the findings potentially more generalizeable, this study is distinctive in that it examines genotype-by-ethnicity interactions, which are unique compared to other published literature. This study sample also represents the three primary sub-populations in the American culture, and is particularly noteworthy given that these ethnic minorities will be more populous than non-Hispanic whites by 2050 [85]. Consequently, it is important to include more than one ethnic group in study samples. Neglecting to do so could result in ill-informed conclusions being applied across groups. Such a myopic approach would seem to further entrench disparities in pain rather than to broaden understanding across ethnicities. Additional research is warranted to uncover the mechanisms influencing ethnic-dependent and genetic associations with pain sensitivity toward new information for enhanced treatment of individuals across ethnic backgrounds.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported by NIH grants NS42754 (RBF) and AG033906 (RBF), NS55094 (BAH), DE019267 (BAH); Training Grant NS045551-02, and General Clinical Research Center Grant RR00082. BAH is also supported as a Health Disparities Scholar of the NIH National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Roger Fillingim, Ph.D. and Jeffrey Mogil, Ph.D. are consultants and equity stock holders in Algynomics, Inc., a company providing research services in personalized pain medication and diagnostics.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- [1].Anderson KO, Green CR, Payne R. Racial and ethnic disparities in pain: causes and consequences of unequal care. J Pain. 2009;10:1187–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Antonaci F, Sand T, Lucas GA. Pressure algometry in healthy subjects: inter-examiner variability. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1998;30:3–8. doi: 10.1080/003655098444255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Baker TA, Green CR. Intrarace differences among black and white americans presenting for chronic pain management: the influence of age, physical health, and psychosocial factors. Pain Med. 2005;6:29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bisgaard T, Klarskov B, Rosenberg J, Kehlet H. Characteristics and prediction of early pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Pain. 2001;90:261–269. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00406-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bond C, LaForge KS, Tian M, Melia D, Zhang S, Borg L, Gong J, Schluger J, Strong JA, Leal SM, Tischfield JA, Kreek MJ, Yu L. Single-nucleotide polymorphism in the human mu opioid receptor gene alters beta-endorphin binding and activity: possible implications for opiate addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9608–9613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Campbell CM, Edwards RR, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences in responses to multiple experimental pain stimuli. Pain. 2005;113:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Campbell CM, France CR, Robinson ME, Logan HL, Geffken GR, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences in diffuse noxious inhibitory controls. J Pain. 2008;9:759–766. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cepeda MS, Farrar JT, Roa JH, Boston R, Meng QC, Ruiz F, Carr DB, Strom BL. Ethnicity influences morphine pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;70:351–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cheng KI, Lin SR, Chang LL, Wang JY, Lai CS. Association of the functional A118G polymorphism of OPRM1 in diabetic patients with foot ulcer pain. J Diabetes Complications. 2010;24:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chou WY, Wang CH, Liu PH, Liu CC, Tseng CC, Jawan B. Human opioid receptor A118G polymorphism affects intravenous patient-controlled analgesia morphine consumption after total abdominal hysterectomy. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:334–337. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200608000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chou WY, Yang LC, Lu HF, Ko JY, Wang CH, Lin SH, Lee TH, Concejero A, Hsu CJ. Association of mu-opioid receptor gene polymorphism (A118G) with variations in morphine consumption for analgesia after total knee arthroplasty. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:787–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Diatchenko L, Nackley-Neely AG, Slade GD, Bhalang K, Belfer I, Max MB, Goldman D, Maixner W. Catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphisms are associated with multiple pain-evoking stimuli. Pain. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Diatchenko L, Slade GD, Nackley AG, Bhalang K, Sigurdsson A, Belfer I, Goldman D, Xu K, Shabalina SA, Shagin D, Max MB, Makarov SS, Maixner W. Genetic basis for individual variations in pain perception and the development of a chronic pain condition. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:135–143. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Edwards CL, Fillingim RB, Keefe FJ. Race, ethnicity and pain: a review. Pain. 2001;94:133–137. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00408-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fillingim RB, Kaplan L, Staud R, Ness TJ, Glover TL, Campbell CM, Mogil JS, Wallace MR. The A118G single nucleotide polymorphism of the mu-opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) is associated with pressure pain sensitivity in humans. J Pain. 2005;6:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fischer AA. Reliability of the pressure algometer as a measure of myofascial trigger point sensitivity [letter] Pain. 1987;28:411–414. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Forsythe LP, Thorn B, Day M, Shelby G. Race and sex differences in primary appraisals, catastrophizing, and experimental pain outcomes. J Pain. 2011;12:563–572. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Fukuda K, Hayashida M, Ide S, Saita N, Kokita Y, Kasai S, Nishizawa D, Ogai Y, Hasegawa J, Nagashima M, Tagami M, Komatsu H, Sora I, Koga H, Kaneko Y, Ikeda K. Association between OPRM1 gene polymorphisms and fentanyl sensitivity in patients undergoing painful cosmetic surgery. Pain. 2009;147:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fukuda K, Hayashida M, Ikeda K, Koukita Y, Ichinohe T, Kaneko Y. Diversity of opioid requirements for postoperative pain control following oral surgery--is it affected by polymorphism of the mu-opioid receptor? Anesth Prog. 2010;57:145–149. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006-57.4.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Fukuda K, Hayashida M, Ikeda K, Koukita Y, Ichinohe T, Kaneko Y. Diversity of opioid requirements for postoperative pain control following oral surgery--is it affected by polymorphism of the mu-opioid receptor? Anesth Prog. 2010;57:145–149. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006-57.4.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Granges G, Littlejohn G. Pressure pain threshold in pain-free subjects, in patients with chronic regional pain syndromes, and in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome [see comments] Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36:642–646. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, Kalauokalani DA, Lasch KE, Myers C, Tait RC, Todd KH, Vallerand AH. The unequal burden of pain: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med. 2003;4:277–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, Kalauokalani DA, Lasch KE, Myers C, Tait RC, Todd KH, Vallerand AH. The unequal burden of pain: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med. 2003;4:277–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, Campbell LC, Decker S, Fillingim RB, Kaloukalani DA, Lasch KE, Myers C, Tait RC, Todd KH, Vallerand AH. The unequal burden of pain: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med. 2003;4:277–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Green CR, Baker TA, Sato Y, Washington TL, Smith EM. Race and chronic pain: a comprehensive study of young black and white americans presenting for management. Journal of Pain. 2003;4:176–183. doi: 10.1016/s1526-5900(02)65013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Green CR, Hart-Johnson T. The impact of chronic pain on the health of black and white men. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102:321–331. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30604-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Green CR, Montague L, Hart-Johnson TA. Consistent and Breakthrough Pain in Diverse Advanced Cancer Patients: A Longitudinal Examination. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Green CR, Ndao-Brumblay SK, Nagrant AM, Baker TA, Rothman E. Race, age, and gender influences among clusters of African American and white patients with chronic pain. J Pain. 2004;5:171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.02.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Green CR, Wheeler JR. Physician variability in the management of acute postoperative and cancer pain: a quantitative analysis of the Michigan experience. Pain Med. 2003;4:8–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hastie BA, Riley JL, III, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences in pain coping: factor structure of the coping strategies questionnaire and coping strategies questionnaire-revised. J Pain. 2004;5:304–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hastie BA, Riley JL, III, Robinson ME, Glover T, Campbell CM, Staud R, Fillingim RB. Cluster analysis of multiple experimental pain modalities. Pain. 2005;116:227–237. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hayashida M, Nagashima M, Satoh Y, Katoh R, Tagami M, Ide S, Kasai S, Nishizawa D, Ogai Y, Hasegawa J, Komatsu H, Sora I, Fukuda K, Koga H, Hanaoka K, Ikeda K. Analgesic requirements after major abdominal surgery are associated with OPRM1 gene polymorphism genotype and haplotype. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:1605–1616. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.11.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hernandez-Avila CA, Covault J, Wand G, Zhang H, Gelernter J, Kranzler HR. Population-specific effects of the Asn40Asp polymorphism at the mu-opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) on HPA-axis activation. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007;17:1031–1038. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282f0b99c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Holliday KL, Nicholl BI, Macfarlane GJ, Thomson W, Davies KA, McBeth J. Do genetic predictors of pain sensitivity associate with persistent widespread pain? Mol Pain. 2009;5:56. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Huang CJ, Liu HF, Su NY, Hsu YW, Yang CH, Chen CC, Tsai PS. Association between human opioid receptor genes polymorphisms and pressure pain sensitivity in females*. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:1288–1295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ikeda K, Ide S, Han W, Hayashida M, Uhl GR, Sora I. How individual sensitivity to opiates can be predicted by gene analyses. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Janicki PK, Schuler G, Francis D, Bohr A, Gordin V, Jarzembowski T, Ruiz-Velasco V, Mets B. A genetic association study of the functional A118G polymorphism of the human mu-opioid receptor gene in patients with acute and chronic pain. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:1011–1017. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000231634.20341.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Jensen K, Andersen HO, Olesen J, Lindblom U. Pressure-pain threshold in human temporal region. Evaluation of a new pressure algometer. Pain. 1986;25:313–323. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Jensen MP, Karoly P, Braver S. The measurement of clinical pain intensity; a comparison of six methods. Pain. 1986;27:117–126. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Jimenez N, Seidel K, Martin LD, Rivara FP, Lynn AM. Perioperative analgesic treatment in Latino and non-Latino pediatric patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:229–236. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Johnson JA. Influence of race or ethnicity on pharmacokinetics of drugs. J Pharm Sci. 1997;86:1328–1333. doi: 10.1021/js9702168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kaiko RF, Wallenstein SL, Rogers AG, Houde RW. Sources of variation in analgesic responses in cancer patients with chronic pain receiving morphine. Pain. 1983;15:191–200. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kamath AF, Horneff JG, Gaffney V, Israelite CL, Nelson CL. Ethnic and gender differences in the functional disparities after primary total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:3355–3361. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1461-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kim H, Clark D, Dionne RA. Genetic contributions to clinical pain and analgesia: avoiding pitfalls in genetic research. J Pain. 2009;10:663–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kim H, Mittal DP, Iadarola MJ, Dionne RA. Genetic predictors for acute experimental cold and heat pain sensitivity in humans. J Med Genet. 2006;43:e40. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.036079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kim H, Neubert JK, Iadarola MJ, San Miguelle A, Goldman D, Dionne RA. Genetic influence on pain sensitivity in humans: evidence of heritability related to single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in opioid receptor genes. In: Dostrovsky JO, Carr DB, Koltzenburg M, editors. Proceedings of the 10th World Congress on Pain. IASP Press; Seattle: 2003. pp. 513–520. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kim H, Neubert JK, San MA, Xu K, Krishnaraju RK, Iadarola MJ, Goldman D, Dionne RA. Genetic influence on variability in human acute experimental pain sensitivity associated with gender, ethnicity and psychological temperament. Pain. 2004;109:488–496. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Klepstad P, Rakvag TT, Kaasa S, Holthe M, Dale O, Borchgrevink PC, Baar C, Vikan T, Krokan HE, Skorpen F. The 118 A > G polymorphism in the human micro-opioid receptor gene may increase morphine requirements in patients with pain caused by malignant disease. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004;48:1232–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2004.00517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kolesnikov Y, Gabovits B, Levin A, Voiko E, Veske A. Combined catechol-O-methyltransferase and mu-opioid receptor gene polymorphisms affect morphine postoperative analgesia and central side effects. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:448–453. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318202cc8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kreek MJ. Role of a functional human gene polymorphism in stress responsivity and addictions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83:615–618. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Kreek MJ, LaForge KS. Stress responsivity, addiction, and a functional variant of the human mu-opioid receptor gene. Mol Interv. 2007;7:74–78. doi: 10.1124/mi.7.2.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kreek MJ, Nielsen DA, LaForge KS. Genes associated with addiction: alcoholism, opiate, and cocaine addiction. Neuromolecular Med. 2004;5:85–108. doi: 10.1385/NMM:5:1:085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Lavernia CJ, Alcerro JC, Contreras JS, Rossi MD. Ethnic and racial factors influencing well-being, perceived pain, and physical function after primary total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1838–1845. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1841-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Lopez L, Wilper AP, Cervantes MC, Betancourt JR, Green AR. Racial and sex differences in emergency department triage assessment and test ordering for chest pain, 1997-2006. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:801–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Lotsch J, Geisslinger G. Relevance of frequent mu-opioid receptor polymorphisms for opioid activity in healthy volunteers. Pharmacogenomics J. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Lotsch J, Stuck B, Hummel T. The human mu-opioid receptor gene polymorphism 118A > G decreases cortical activation in response to specific nociceptive stimulation. Behav Neurosci. 2006;120:1218–1224. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.6.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Lotsch J, Zimmermann M, Darimont J, Marx C, Dudziak R, Skarke C, Geisslinger G. Does the A118G polymorphism at the mu-opioid receptor gene protect against morphine-6-glucuronide toxicity? Anesthesiology. 2002;97:814–819. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200210000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Max MB, Wu T, Atlas SJ, Edwards RR, Haythornthwaite JA, Bollettino AF, Hipp HS, McKnight CD, Osman IA, Crawford EN, Pao M, Nejim J, Kingman A, Aisen DC, Scully MA, Keller RB, Goldman D, Belfer I. A clinical genetic method to identify mechanisms by which pain causes depression and anxiety. Mol Pain. 2006;2:14. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Mechlin B, Heymen S, Edwards CL, Girdler SS. Ethnic differences in cardiovascular-somatosensory interactions and in the central processing of noxious stimuli. Psychophysiology. 2011;48:762–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Mechlin B, Morrow AL, Maixner W, Girdler SS. The relationship of allopregnanolone immunoreactivity and HPA-axis measures to experimental pain sensitivity: Evidence for ethnic differences. Pain. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Mechlin MB, Maixner W, Light KC, Fisher JM, Girdler SS. African Americans show alterations in endogenous pain regulatory mechanisms and reduced pain tolerance to experimental pain procedures. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:948–956. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188466.14546.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Mogil JS, Ritchie J, Smith SB, Strasburg K, Kaplan L, Wallace MR, Romberg RR, Bijl H, Sarton EY, Fillingim RB, Dahan A. Melanocortin-1 receptor gene variants affect pain and mu-opioid analgesia in mice and humans. J Med Genet. 2005;42:583–587. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.027698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Mogil JS, Wilson SG, Chesler EJ, Rankin AL, Nemmani KV, Lariviere WR, Groce MK, Wallace MR, Kaplan L, Staud R, Ness TJ, Glover TL, Stankova M, Mayorov A, Hruby VJ, Grisel JE, Fillingim RB. The melanocortin-1 receptor gene mediates female-specific mechanisms of analgesia in mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4867–4762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730053100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Moore PA, Duncan GH, Scott DS, Gregg JM, Ghia JN. The submaximal effort tourniquet test: its use in evaluating experimental and chronic pain. Pain. 1979;6:375–382. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(79)90055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Nielsen DA, Hamon S, Yuferov V, Jackson C, Ho A, Ott J, Kreek MJ. Ethnic diversity of DNA methylation in the OPRM1 promoter region in lymphocytes of heroin addicts. Hum Genet. 2010;127:639–649. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0807-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Pertovaara A, Nurmikko T, Pontinen PJ. Two seperate components of pain produced by the submaximal effort tourniquet test. Pain. 1984;20:53–58. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(84)90810-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Plesh O, Adams SH, Gansky SA. Racial/Ethnic and gender prevalences in reported common pains in a national sample. J Orofac Pain. 2011;25:25–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Plesh O, Crawford PB, Gansky SA. Chronic pain in a biracial population of young women. Pain. 2002;99:515–523. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00262-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Rahim-Williams FB, Riley JL, III, Herrera D, Campbell CM, Hastie BA, Fillingim RB. Ethnic identity predicts experimental pain sensitivity in African Americans and Hispanics. Pain. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Reyes-Gibby CC, Shete S, Rakvag T, Bhat SV, Skorpen F, Bruera E, Kaasa S, Klepstad P. Exploring joint effects of genes and the clinical efficacy of morphine for cancer pain: OPRM1 and COMT gene. Pain. 2007;130:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Reyes-Gibby CC, Shete S, Rakvag T, Bhat SV, Skorpen F, Bruera E, Kaasa S, Klepstad P. Exploring joint effects of genes and the clinical efficacy of morphine for cancer pain: OPRM1 and COMT gene. Pain. 2007;130:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Shinal RM, Glover T, Williams RS, Staud R, Riley JL, III, Fillingim RB. Evaluation of menstrual cycle effects on morphine and pentazocine analgesia. Pain. 2011;152:614–622. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Schiff E, Eisenberg E. Can quantitative sensory testing predict the outcome of epidural steroid injections in sciatica? A preliminary study. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:828–832. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000078583.47735.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Shabalina SA, Zaykin DV, Gris P, Ogurtsov AY, Gauthier J, Shibata K, Tchivileva IE, Belfer I, Mishra B, Kiselycznyk C, Wallace MR, Staud R, Spiridonov NA, Max MB, Goldman D, Fillingim RB, Maixner W, Diatchenko L. Expansion of the human mu-opioid receptor gene architecture: novel functional variants. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:1037–1051. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Sia AT, Lim Y, Lim EC, Goh RW, Law HY, Landau R, Teo YY, Tan EC. A118G single nucleotide polymorphism of human mu-opioid receptor gene influences pain perception and patient-controlled intravenous morphine consumption after intrathecal morphine for postcesarean analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:520–526. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318182af21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Sternberg WF, Bailin D, Grant M, Gracely RH. Competition alters the perception of noxious stimuli in male and female athletes. Pain. 1998;76:231–238. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Tan EC, Lim EC, Teo YY, Lim Y, Law HY, Sia AT. Ethnicity and OPRM variant independently predict pain perception and patient-controlled analgesia usage for post-operative pain. Mol Pain. 2009;5:32. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-5-32. 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Tan EC, Lim Y, Teo YY, Goh R, Law HY, Sia AT. Ethnic differences in pain perception and patient-controlled analgesia usage for postoperative pain. J Pain. 2008;9:849–855. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Tan EC, Sia AT. Effect of OPRM variant on labor analgesia and post-cesarean delivery analgesia. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2010;19:458–459. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Tegeder I, Lotsch J. Current evidence for a modulation of low back pain by human genetic variants. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:1605–1619. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00703.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Todd KH, Deaton C, D’Adamo AP, Goe L. Ethnicity and analgesic practice. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:11–16. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(00)70099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Todd KH, Green C, Bonham VL, Jr., Haywood C, Jr., Ivy E. Sickle cell disease related pain: crisis and conflict. J Pain. 2006;7:453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Todd KH, Lee T, Hoffman JR. The effect of ethnicity on physician estimates of pain severity in patients with isolated extremity trauma [see comments] JAMA. 1994;271:925–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Todd KH, Samaroo N, Hoffman JR. Ethnicity as a risk factor for inadequate emergency department analgesia. JAMA. 1993;269:1537–1539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].United States Census Bureau United States Census 2010. 2011. internet.

- [86].Walter C, Lotsch J. Meta-analysis of the relevance of the OPRM1 118A>G genetic variant for pain treatment. Pain. 2009;146:270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Wand GS, McCaul M, Yang X, Reynolds J, Gotjen D, Lee S, Ali A. The mu-opioid receptor gene polymorphism (A118G) alters HPA axis activation induced by opioid receptor blockade. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:106–114. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Wu WD, Wang Y, Fang YM, Zhou HY. Polymorphism of the micro-opioid receptor gene (OPRM1 118A>G) affects fentanyl-induced analgesia during anesthesia and recovery. Mol Diagn Ther. 2009;13:331–337. doi: 10.1007/BF03256337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Zhang W, Chang YZ, Kan QC, Zhang LR, Lu H, Chu QJ, Wang ZY, Li ZS, Zhang J. Association of human micro-opioid receptor gene polymorphism A118G with fentanyl analgesia consumption in Chinese gynaecological patients. Anaesthesia. 2010;65:130–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.06193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Zhang W, Yuan JJ, Kan QC, Zhang LR, Chang YZ, Wang ZY. Study of the OPRM1 A118G genetic polymorphism associated with postoperative nausea and vomiting induced by fentanyl intravenous analgesia. Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77:33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Zhang Y, Wang D, Johnson AD, Papp AC, Sadee W. Allelic expression imbalance of human mu opioid receptor (OPRM1) caused by variant A118G. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32618–32624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Zwisler ST, Enggaard TP, Noehr-Jensen L, Mikkelsen S, Verstuyft C, Becquemont L, Sindrup SH, Brosen K. The antinociceptive effect and adverse drug reactions of oxycodone in human experimental pain in relation to genetic variations in the OPRM1 and ABCB1 genes. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2009.00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]